Abstract

Introduction

Forced vital capacity is the only registrational endpoint in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis clinical trials. As most new treatments will be administered on top of standard of care, estimating treatment response will become more challenging. We developed a simulation model to quantify variability associated with forced vital capacity decline.

Methods

The model is based on publicly available clinical trial summary and home spirometry data. A single, illustrative trial setting is reported. Model assumptions are 400 subjects randomised 1:1 to investigational drug or placebo over 52 weeks, 50% of each group receiving standard of care (all-comer population), and a 90-mL treatment difference in annual forced vital capacity decline. Longitudinal profiles were simulated and the impact of varying clinical scenarios evaluated.

Results

Power to detect a significant treatment difference was 87–97%, depending on the analysis method. Repeated measures analysis generally outperformed analysis of covariance and mixed linear models, particularly with missing data (as simulated data were non-linear). A 15% yearly random dropout rate led to 0.6–5% power loss. Forced vital capacity decline-related dropout introduced greater power loss (up to 12%), as did subjects starting/stopping standard of care or investigational drug. Power was substantially lower for a 26-week trial due to the smaller assumed treatment effect at week 26 (sample size would need doubling to reach a power similar to that of a 52-week trial).

Conclusions

Our model quantifies forced vital capacity decline and associated variability, with all the caveats of background therapy, permitting robust power calculations to inform future idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis clinical trial design.

Funding

Galapagos NV (Mechelen, Belgium).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is characterised by progressive fibrosis and high mortality [1, 2]. Current standard of care (SOC) is treatment with the antifibrotic agents pirfenidone or nintedanib [3, 4], which slow, but do not halt, progression [5,6,7]. Both are associated with side effects, such as gastrointestinal and skin-related adverse events, which contribute to treatment discontinuation rates of 21–26% [8]. New treatments with fewer side effects are needed.

Forced vital capacity (FVC) decline is a surrogate endpoint for death in IPF studies [9] and formed the basis of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of pirfenidone and nintedanib [10]. Novel drugs will likely need to demonstrate efficacy with respect to FVC when administered on top of SOC, which will be challenging. Given the complexities of such trials, it is essential to understand the range of FVC decline in this setting. Modelling and simulations can predict the pattern of decline under different scenarios and inform trial design and power calculations. However, modelling to estimate treatment effects is not straightforward and interpretation is complicated by many factors. These include intrinsic variability of FVC, influence of co-morbidities, uncertainty about treatment response durability, and variable time–exposure relationships due to dose interruptions, dose reductions and change of SOC treatment—particularly in trials of long duration. Mortality, dropouts and uncertainty regarding the predictive value of prior FVC decline in assessing treatment response add to this complexity [11, 12]. Owing to these difficulties, uncertainties and misconceptions exist regarding the pattern of FVC decline.

We established a model based on publicly available summary data from recent clinical trials and home spirometry data from a study in patients with IPF. Our aim was to quantify the variability associated with FVC decline to model effects of an investigational drug when given on top of background SOC therapy. We used an illustrative example to highlight our findings, which can be adapted or extended to other trial settings.

Methods

In our model, we used source data to simulate longitudinal FVC profiles. Then, using a simplified study design, we interrogated the clinical trial setting and analysed data using three different statistical methods to determine treatment effect size, variability and study power. We did this under a variety of scenarios (such as differing trial dropout rates, reduced investigational drug dose, a change in background treatment and reduced trial duration). We then evaluated the effects of each of these scenarios on treatment effect size, variability and study power.

Source Data

Publicly available summary data were obtained from the FDA medical review of nintedanib [13, 14], including 1066 patients in the double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 INPULSIS trials and 432 patients in a randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging phase 2 study [7, 15]. Pirfenidone data were excluded because the primary endpoint in key studies was percentage predicted FVC (ppFVC), rather than FVC. Daily home spirometry data were obtained from a study in which 50 patients with IPF provided daily FVC readings over a median of 279 days [16]. These data confirmed previous observations of the clinical course of IPF [17], correlated well with hospital-based assessment of FVC and, as measurements were daily, were more sensitive in predicting disease outcome [16].

Model Assumptions and Correlation Structure

Forced vital capacity data were simulated from a multivariate normal distribution, with mean, variance and correlation structure as shown in Table 1. From observed variability in source data, it can be shown that baseline and week 52 FVC are strongly correlated, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.94. A continuous autoregressive model of order 1, CAR(1) [18], was used to specify pairwise correlations between FVC measurements from the same subject at any time point. CAR(1) was selected because it is a straightforward, but realistic, structure for this longitudinal data setting. It assumes that FVC correlation decreases as time between measurements increases, which implies that the variability of FVC change from baseline increases over time (as observed in source data). Also, it fitted well to daily spirometry data (see “Results”). As pirfenidone source data were excluded, assumptions for pirfenidone were the same as for nintedanib. Poor predictability of FVC decline to inform future disease progression has been reported in clinical studies [11, 12, 19, 20]. Nathan et al. [12] reported that changes in ppFVC during two consecutive 6-month intervals had a weak negative correlation (correlation coefficient, − 0.146, p < 0.001). To assess if this could be reproduced using our model, the analysis described by Nathan and colleagues [12] was performed for 10,000 simulations.

Statistical Analysis

Simulated FVC data were analysed by (1) an analysis of covariance model (ANCOVA) per time point with FVC change from baseline as a dependent variable and baseline FVC and treatment as covariates; (2) a repeated measures analysis (MMRM) with FVC change from baseline as a dependent variable and baseline FVC, treatment and time (categorical) as covariates, using an autoregressive error covariance structure; and (3) a linear mixed model (LMM) with FVC actual values as a dependent variable, treatment and time (continuous) as fixed effects and a random intercept and slope (this model assumed a linear trend over time). MMRM and LMM use all available data; therefore, missing data are implicitly accounted for. Fitting these models to the data allowed assessment of the treatment difference in FVC decline, variability (described using 95% confidence intervals, CIs), and the power to detect a significant result (proportion of significant simulations, at 5% significance level). R (version 3.5.2.) software was used for simulations and statistical analysis.

Base Simulation Setting

In our illustrative clinical trial setting, we assumed that 400 subjects with IPF would be randomised 1:1 to investigational drug or placebo, across two strata. It was assumed that half were taking SOC (pirfenidone/nintedanib) at the start of the study and half were not. Subjects were not required to remain on SOC, but could stop/start SOC during the trial, therefore representing an all-comer patient population. Simulations encompassed FVC measurements at weeks 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 18, 26, 34, 42 and 52. Assumed treatment difference in FVC change from baseline at week 52 for investigational drug versus placebo was 90 mL overall (60 mL for subjects on background pirfenidone/nintedanib, 120 mL for subjects who were not on background therapy). These were considered realistic assumptions based on the extrapolation of treatment effects reported in IPF trials, such as INSTAGE (mean change from baseline in FVC at week 24, − 20.8 mL for nintedanib plus sildenafil vs − 58.2 mL for nintedanib alone) [21], INJOURNEY (mean change from baseline in FVC at week 12, − 13.3 mL for nintedanib plus pirfenidone vs − 40.9 mL for nintedanib alone) [22] and a phase 2 trial of an investigational drug PBI-4050 (mean change from baseline in FVC at week 12, + 2 mL for nintedanib plus PBI-4050) [23].

Simulation Scenarios

We modelled various trial scenarios to estimate their effects on FVC decline in our illustrative trial setting and potential implications for trial design and powering. First, we evaluated the potential impact of missing data due to subjects (1) randomly dropping out of the trial (at an annual rate of less than or equal to 15%); (2) dropping out at different rates in the two treatment groups; (3) dropping out due to an observed/unobserved decrease in FVC decline. We then modelled the effect of initiating SOC during the trial in placebo subjects who were not taking SOC prior to trial initiation. We modelled scenarios in which subjects on SOC discontinued or lowered their dose of investigational drug (the treatment effect of the lower dose was assumed to be half that of the higher dose; this assumption was made for modelling purposes to clearly illustrate an effect and not based on real data). We also assessed the combined effect of dropout and initiating SOC within the same scenario. In addition, we evaluated the effects of shortening trial length from 52 to 26 weeks. Finally, we assessed the effect of disease progression in placebo subjects not receiving SOC. Subjects were categorised as ‘rapid’ or ‘slow’ progressors according to FVC decline in 6 months (greater than 10% or less than 10% decline, respectively) and this was compared with the following 6 months. This analysis was performed to re-evaluate the results reported by Biondini and co-workers [24], which showed that pirfenidone treatment led to a greater reduction in the rate of FVC decline in ‘rapid’ versus ‘slow’ progressors.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Simulation Model and Correlation Structure

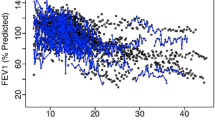

Examples of data simulation outputs are shown in Figs. 1, 2 and 3 (individual profiles for Figs. 2, 3 are presented in Figs. S1 and S2, respectively—see the electronic supplementary material).

Examples of FVC data simulation output using our illustrative clinical trial setting. Ten randomly selected profiles from subjects with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis randomised to investigational drug (a) or placebo (b), with half taking SOC (pirfenidone/nintedanib) at the start of the study. FVC forced vital capacity, SOC standard of care

Examples of two data simulation outputs (a, b) using our illustrative clinical trial setting. Each plot shows mean change from baseline (with and without SOC; pirfenidone/nintedanib) from one simulation (n = 200 per treatment arm). FVC forced vital capacity, SEM standard error of the mean, SOC standard of care

Examples of two data simulation outputs (a, b result from simulation 1; c, d result from simulation 2) using our illustrative clinical trial setting. Each row shows mean change from baseline from one simulation, with (a, c) and without (b, d) SOC (pirfenidone/nintedanib) treatment (n = 100 per treatment group–strata combination). FVC forced vital capacity, SEM standard error of the mean, SOC standard of care

The CAR(1) correlation structure provided a good fit to daily spirometry data. A more complex, flexible model incorporating a random slope and intercept in addition to a CAR(1) error covariance matrix was also assessed, but provided only a slightly better fit (improvement of 0.7% in Akaike information criterion), implying that the CAR(1) model is sufficient for capturing the underlying correlation structure. Under this assumption, a similar result as described by Nathan and colleagues [12] was found: mean correlation coefficient between FVC decline in the first and second 6-month intervals for placebo subjects not receiving SOC over 10,000 simulations was − 0.014 (95% CI − 0.21, 0.18).

Base Simulation Setting

Our modelled 52-week clinical trial had a power of 87–97% to detect a significant treatment difference (Table 2 and Fig. 4). LMM performed less well (higher variability and lower power) than other models in this base setting with complete data (due to the model’s linearity assumption and the fact that the simulated data do not follow a perfect linear trend).

Estimated treatment difference from 10,000 data simulations in a 26-week (a) and a 52-week clinical trial setting (b). For each trial duration, results of 10,000 simulations analysed via three different statistical methods (ANCOVA, LMM and MMRM) are shown. ANCOVA analysis of covariance, LMM linear mixed model, MMRM repeated measures analysis

Simulation Scenarios

The impact of dropout scenarios on treatment effect is presented in Table 2. For dropout occurring randomly (missing completely at random, MCAR) at yearly rates of 5%, 10% or 15%, power loss was moderate (up to 5%) and, as expected, ANCOVA was impacted most. The same held true when dropout rates differed between treatment groups; however, this introduced a small bias in the treatment difference as estimated by LMM: a higher dropout with placebo versus drug led to a small overestimation of treatment effect and vice versa. In contrast, the impact was more pronounced for FVC decline-related dropout. ANCOVA performed poorly in both scenarios, i.e. when dropout resulted from an observed, confirmed FVC decline of greater than 10% (missing at random, MAR) and when dropout preceded an unobserved, confirmed FVC decline of greater than 10% (missing not at random, MNAR). Treatment effect was underestimated; power loss was 9% and 12%, respectively. MMRM and LMM performed better in this setting. Results were affected moderately under MNAR (power loss of 3% for MMRM and 5% for LMM). Moreover, MMRM was robust to dropout under MAR, whereas LMM led to an overestimation of treatment effect (94.4 mL; 95% CI 32.4, 157.0). This is due to the linearity assumption of the LMM; in this setting there is higher dropout with placebo versus drug and because dropout follows a steep decline in FVC, the slope estimate is lower than if the full profile was observed.

Power loss would occur if placebo subjects switched from no SOC to SOC from week 26 onwards (Table 3; up to 9% if 50% switched). Similar effects were observed if subjects receiving SOC were to discontinue investigational drug (10% power loss if 50% discontinued). This impact would be smaller (up to 4% loss) if subjects down-titrated to a lower dose of investigational drug, assumed to elicit half the treatment effect of the higher dose.

When combining a 5% dropout under MNAR with 15% of subjects switching from no SOC to SOC from week 26 onwards, as an example of a real-world setting, impact was moderate; power for all methods was still greater than 80% (lowest power of 82% for LMM).

Shortening the trial from 52 to 26 weeks would reduce the power (Fig. 4). Sample size would need to increase to 400 per group to reach similar power as for the 52-week trial simulation. For ANCOVA and MMRM, this is due to the decrease in assumed treatment effect in change from baseline at week 26, which outweighs the smaller variability. LMM estimates the same underlying yearly rate (90 mL), and is affected by increased variability due to fewer observed data points at week 26.

For placebo subjects not receiving SOC, and on stable placebo treatment for 52 weeks, FVC decline in the second 6-month period would be significantly reduced for ‘rapid progressors’ (358 mL in the first period, 70 mL in the second; p < 0.0001), illustrating a case of ‘regression to the mean’. For ‘slow progressors’ FVC decline would be increased (49 mL in the first period, 90 mL in the second; p = 0.14).

Discussion

Forced vital capacity is intrinsically variable and, when coupled with the unpredictable nature of IPF disease progression, evaluating change in this measure is difficult, particularly on a per patient basis over long periods of time. In addition, clinical trials in IPF are complex and likely to become more so as studies begin to investigate treatment combinations. Therefore, we used a variety of trial scenario simulations to understand the nature of the problem, utilising nintedanib summary data and home spirometry data from IPF patients. In our simulation setting, 400 subjects (with or without background SOC therapy) were randomised 1:1 to investigational drug or placebo. Our modelling estimated that, assuming a treatment difference of 90 mL at 1 year, this illustrative trial would have 87–97% power to detect a significant treatment effect. We found that several complexities inherent to an all-comer population, such as subjects starting/stopping treatment, could impact the primary analysis results. We illustrated how certain causes of dropout (MAR and MNAR) could result in a biased treatment effect and power decline. Furthermore, reducing trial duration from 52 to 26 weeks would require a considerably larger sample size to achieve a similar power. Results of mixed models (MMRM and LMM) were quite robust to the scenarios under consideration, and were only markedly affected by extreme scenarios. These results are an illustration of the capabilities of the model in informing clinical trial design and highlight aspects that could be adapted for application to other clinical trial settings.

Nathan and colleagues demonstrated that changes in ppFVC during two consecutive 6-month intervals had a weak negative correlation, concluding that this was indicative of substantial variability [12]. Our simulation results confirmed that a weak negative correlation is also observed under our assumed correlation structure. Moreover, it can be shown that under any CAR(1) structure, independent of the assumed variability, true correlation between FVC changes in consecutive time intervals for subjects receiving the same treatment (SOC or investigational drug) is always negative. Furthermore, the higher the autocorrelation between FVC measurements, the closer the correlation between consecutive FVC changes will be to zero. Thus, a weak negative correlation between FVC changes does not necessarily imply high variability. Rather, we suggest that it could indicate that the subjects under consideration follow the same underlying mean FVC trend, with highly correlated observations over time.

Others have also investigated the predictability of FVC decline for future lung function progression. Analysis of a large multicentre, retrospective cohort of patients with IPF showed that change in pulmonary function in the previous year was not a good predictor of subsequent changes, but did predict mortality in the following 12 months [11]. Another study similarly showed that FVC decline was not predictive of short-term risk of disease progression, but did predict respiratory hospitalisations and death [19]. A post hoc analysis of the nintedanib INPULSIS trial reported that FVC decline in the first 24 weeks did not predict decline in the subsequent 24 weeks [20] but did predict mortality at 52 weeks. These findings support our observations and have important implications for clinical practice.

In further support of this notion, Biondini et al. [24] reported that pirfenidone significantly reduced the rate of FVC decline and that this was more pronounced in ‘rapid’ versus ‘slow’ progressors. However, we suggest that such conclusions cannot be drawn on the basis of the design of Biondini’s study (which lacked a placebo group), as similar results were obtained in our simulations of placebo data, without an underlying treatment effect. Thus, there is a need to differentiate between treatment effect and the untreated longitudinal behaviour of FVC to avoid, in this case, overestimation of treatment effect in ‘rapid progressors’ and underestimation in ‘slow progressors’, which is a typical example of regression to the mean. Additionally, while its longitudinal behaviour is interesting for modelling purposes, the clinical implication of a decline in FVC of 10% is that it is associated with a higher risk of mortality in the near term. The clinical pattern after a decline of this magnitude varies from early death to the other extreme of a significantly slower decline in FVC. This may not be obvious in shorter trials and is more obvious over longer periods [11]. Thus, the terms ‘rapid progressor’ and ‘slow progressor’ are likely a misnomer.

A strength of the current analysis is that it illustrates the feasibility of quantifying FVC variability using a relatively simple model and the impact of clinical trial scenarios in a SOC setting. This modelling is assumption-based, which is subject to inherent limitations (for example, to examine the effects of lowering dose, we made an assumption regarding the dose–response nature of the treatment effect, which may vary between investigational drugs). However, we believe that the assumptions are reasonable and, as they are based on publicly available data, they can be updated as more data become available. Source data partially came from daily home monitoring of FVC by patients, which has shown good agreement with hospital-recorded spirometry [16, 25]. A limitation of the study is that the data on which the model is based were obtained from clinical trial populations which, by their nature, are subject to selection biases. While this may accurately reflect clinical research patient populations, it may limit the application of the model to real-world settings. However, the robustness of the model can be further improved as additional source data sets become available. Finally, we were unable to explicitly model some clinical aspects affecting FVC in individual patients—such as acute IPF exacerbations or underlying genetic factors—although these likely contribute to the reported variability in the literature, thus having an implicit impact on the model.

Conclusions

Future clinical trials of IPF treatments will likely need to demonstrate the effect of an investigational drug on top of SOC. We demonstrate that many clinical scenarios, such as FVC decline-related dropout, starting/stopping treatment, and a shortened clinical trial period, can affect power calculations in such trials. While the LMM model performed less well in terms of variability and power than ANCOVA or MMRM with complete data, LMM and MMRM performed better under the tested scenarios. We demonstrate the need to distinguish between treatment effect and underlying changes in FVC to correctly attribute changes to treatment, background therapy, or FVC variation. These findings will help optimise future clinical trial design.

References

Barratt SL, Creamer A, Hayton C, Chaudhuri N. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF): an overview. J Clin Med. 2018;7:201.

Torrisi SE, Pavone M, Vancheri A, Vancheri C. When to start and when to stop antifibrotic therapies. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26:170053.

Raghu G, Rochwerg B, Zhang Y, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline: treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An update of the 2011 clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192:e3–19.

Raghu G, Selman M. Nintedanib and pirfenidone. New antifibrotic treatments indicated for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis offer hopes and raises questions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:252–4.

Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;377:1760–9.

King TE Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2083–92.

Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2071–82.

Galli JA, Pandya A, Vega-Olivo M, Dass C, Zhao H, Criner GJ. Pirfenidone and nintedanib for pulmonary fibrosis in clinical practice: tolerability and adverse drug reactions. Respirology. 2017;22:1171–8.

Ley B. Clarity on endpoints for clinical trials in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:1383–4.

Karimi-Shah BA, Chowdhury BA. Forced vital capacity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis—FDA review of pirfenidone and nintedanib. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1189–91.

Schmidt SL, Tayob N, Han MK, et al. Predicting pulmonary fibrosis disease course from past trends in pulmonary function. Chest. 2014;145:579–85.

Nathan SD, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. Effect of continued treatment with pirfenidone following clinically meaningful declines in forced vital capacity: analysis of data from three phase 3 trials in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax. 2016;71:429–35.

Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Application number: 205832Orig1s000 medical review(s)—Nintedanib. 2014. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2014/205832Orig1s000MedR.pdf. Accessed 13 Sept 2019.

Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Application number: 022535Orig1s000 medical review(s)—Pirfenidone. 2014. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2014/022535Orig1s000MedR.pdf. Accessed 13 Sept 2019.

Richeldi L, Costabel U, Selman M, et al. Efficacy of a tyrosine kinase inhibitor in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1079–87.

Russell AM, Adamali H, Molyneaux PL, et al. Daily home spirometry: an effective tool for detecting progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:989–97.

Ley B, Collard HR, King TE. Clinical course and prediction of survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:431–40.

Chatfield C. The analysis of time series: an introduction. Texts in statistical science. 6th ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2016.

Ley B, Bradford WZ, Vittinghoff E, Weycker D, du Bois RM, Collard HR. Predictors of mortality poorly predict common measures of disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194:711–8.

Richeldi L, Azuma A, Selman M, et al. Twenty-four week decline in forced vital capacity predicts mortality at week 52 in the INPULSIS® trials. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:OA1814.

Kolb M, Raghu G, Wells AU, et al. Nintedanib plus sildenafil in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1722–31.

Vancheri C, Kreuter M, Richeldi L, et al. Nintedanib with add-on pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Results of the INJOURNEY trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:356–63.

Gagnon L, Grouix B, Laverdure A, et al. Evaluation of the effect of PBI-4050 alone or in combination with pirfenidone or nintedanib on blood biomarkers linked to the fibrotic process in IPF patients. Abstract #A2439. Presented at the American Thoracic Society Conference 2018. 2018. https://www.abstractsonline.com/pp8/#!/4499/presentation/11213. Accessed 13 Sept 2019.

Biondini D, Balestro E, Lacedonia D, et al. Pretreatment rate of decay in forced vital capacity predicts long-term response to pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:5961.

Moor CC, Wapenaar M, Miedema JR, Geelhoed JJM, Chandoesing PP, Wijsenbeek MS. A home monitoring program including real-time wireless home spirometry in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a pilot study on experiences and barriers. Respir Res. 2018;19:105.

Acknowledgements

Funding

The research and Rapid Service Fee was funded by Galapagos NV (Mechelen, Belgium). All authors had full access to all of the data in this study.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing support (including development of drafts in consultation with the authors, assembling tables and figures, collating author comments, copyediting, fact checking and referencing) was provided by Alice Wareham PhD, CMPP at Aspire Scientific (Bollington, UK). Support for this assistance was funded by Galapagos NV (Mechelen, Belgium).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

Eva Santermans contributed to the study design, data collection and data analysis. Adam J. Byrne, Philip L. Molyneaux, Arunon Sivananthan and Toby M. Maher contributed to data collection.

Disclosures

Eva Santermans is an employee of Galapagos. Paul Ford is an employee of, and has received warrants from, Galapagos. Nadia Verbruggen is an employee of, and has received warrants from, Galapagos. Paul Meyvisch is an employee of, and has received warrants from, Galapagos. Michael Kreuter reports grants and personal fees from Galapagos during the conduct of the study, and grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche outside the submitted work. Wim A. Wuyts reports no personal fees; the University Hospitals Leuven received consultancy fees from Galapagos during the conduct of the study and grants from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche outside the submitted work. Kevin K. Brown reports grants from the National Institutes of Health, and advisory board participation for Biogen, Blade, Boehringer Ingelheim, Galapagos, Galecto, Genoa, Huitai Biomedicine, Lifemax, MedImmune, monARC Bionetworks, Open Source Imaging Consortium (OSIC), Pliant, ProMetic, Theravance, Third Pole, Three Lakes Partners, and Veracyte outside the submitted work. David J. Lederer is a fulltime employee of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. He also reports personal fees from Galapagos during the conduct of the study, prior personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim relating to studies used as source data in the current study, and personal fees from Philips Respironics, Roche, Sanofi Genzyme and Veracyte, grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Fibrogen, and Global Blood Therapeutics, unpaid Steering Committee membership for Galecto, unpaid advisory board membership and consultancy for Pliant, unpaid consultancy for Bristol-Myers Squibb, and institutional fees for consultancy work from the Pulmonary Fibrosis Foundation outside the submitted work. Adam J. Byrne, Catharina C. Moor and Arunon Sivananthan have nothing to disclose. Philip L. Molyneaux and his institution have received speaker and advisory board fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Hoffmann-La Roche outside the submitted work. Toby M. Maher via his institution, has received industry-academic funding from GlaxoSmithKline R&D and UCB, and has received consultancy or speakers fees from Apellis, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Blade Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Galapagos, GlaxoSmithKline R&D, Indalo, Novartis, Pliant, ProMetic, Respivnat, Roche, Samumed, and UCB outside the submitted work. Marlies Wijsenbeek reports no personal fees; the Erasmus MC received an advisory board fee from Galapagos, and speaker and advisory board fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Hoffmann-La Roche outside the submitted work.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The home spirometry data analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The R code for the simulation model and analyses are included in the supplementary information (Appendix 1 in the electronic supplementary material).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

David J. Lederer’s details indicate the affiliation at the time the study was conducted.

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9785642.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Santermans, E., Ford, P., Kreuter, M. et al. Modelling Forced Vital Capacity in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Optimising Trial Design. Adv Ther 36, 3059–3070 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01093-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-01093-3