Abstract

Bladder and kidney cancer are the 10th and 7th most common cancers in the United Kingdom (UK). They present with symptoms that are typically investigated via the same diagnostic pathway. However, diagnosing these cancers can be challenging, especially for kidney cancer, as many of the symptoms are non-specific and occur commonly in patients without cancer. Furthermore, the recognition and evaluation of these symptoms may differ because of the lack of supporting high-quality evidence to inform management, a problem also reflected in currently ambiguous guidelines. The majority of these two cancers are diagnosed following a referral from a general practitioner. In this article, we summarise current UK and United States (US) guidelines for investigating common symptoms of bladder and kidney cancer—visible haematuria, non-visible haematuria and urinary tract infections. Our article aims to support clinicians in recognising and investigating patients with symptoms of possible bladder and kidney cancer in a timely fashion. We discuss challenges during the diagnostic process and possible future interventions for improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Around 10,000 and 12,500 patients were diagnosed with bladder and kidney cancer respectively in the UK in 2015 [1]. While the incidence of bladder cancer is predicted to remain stable, kidney cancer is expected to be among the cancers with the fastest increasing incidence over the next 20 years [2]. Currently, these cancers are more common in men than women, with men being about 3 times and 1.7 times as likely as women to be diagnosed with bladder and kidney cancer respectively [2, 3].

In the UK, most bladder cancer (almost 70%) is diagnosed following a referral from a general practitioner (GP) [3]. The percentage of those diagnosed via a fast-track GP referral (“two-week-wait” referral in England) has been increasing year on year from 38% in 2011 to 43% of all bladder cancer diagnosed in 2015 [3]. This may partly reflect public health interventions such as the “Be Clear on Cancer” campaign, aiming to increase public awareness of alarm symptoms such as haematuria [4]; further, it may be related to progressive changes in clinical practice due to the implementation of clinical guidelines, clinical audit initiatives and the introduction of new referral pathways. Kidney cancer patients, on the other hand, have a more varied route to diagnosis. Although almost 60% are still diagnosed following a GP referral; about a third (28% and 31% respectively) were diagnosed via the fast-track and non-fast track route in 2015 [3]. Kidney cancer is also associated with a slightly higher rate of emergency presentation than bladder cancer, with about a fifth (21% and 18% respectively) diagnosed through an emergency route [3], which is associated with poorer stage at diagnosis and survival [5]. Given that the majority of these two cancers are diagnosed following presentation in primary care, timely recognition, diagnostic testing and referral decisions by GPs are paramount to improve outcomes [6].

Current evidence indicates that women with bladder cancer experience a longer time to diagnosis, more advanced stage at diagnosis and worse survival, even if adjusted for stage at diagnosis, than men [7,8,9,10]. The effects of different exposures to risk factors and the role of biological mechanisms, such as sex steroids triggering cancer development and influencing treatment effects, have been implicated in gender disparities in cancer incidence and survival [11, 12]. However, it is likely that variable diagnostic testing strategies by clinicians also contribute to the observed differences in how quickly these cancers are diagnosed.

We provide an overview of current relevant UK and US guidelines, highlight their limitations and suggest a practical approach to the evaluation of patients presenting in primary care with symptoms of possible bladder or kidney cancer. We focused on the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines (developed in England and also adopted and in use in Wales and Northern Ireland), Scottish and American guidelines to present recommendations from three systematically developed guidelines to guide the discussion, highlight discrepancies and areas for future research. As the symptoms of and initial investigations for these two cancers are similar, we consider them together. Hereafter urological cancers denote bladder and kidney cancers only (and not prostate cancer), unless otherwise stated. Although sections of this article focus on the diagnostic pathway in the UK, the principles underlying the evaluation strategies discussed here will be of relevance to primary care clinicians working in countries around the world.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Symptom Signature

Clinicians should consider both the symptom signature of a cancer and the predictive values of possible cancer symptoms during the diagnostic evaluation for possible cancer.

Symptom signature of a cancer refers to the nature and relative frequency of presenting symptom(s) in patients with that cancer. Bladder cancer has a narrow symptom signature dominated by a symptom with high predictive value [13]; that is, most patients with bladder cancer present with haematuria, a symptom with relatively high positive predictive value (PPV). In contrast, kidney cancer has a broad symptom signature with symptoms of varying predictive value, some of which may have relatively high PPVs (e.g. haematuria), while others have low PPVs (e.g. abdominal pain). Taking visible haematuria as an example, it was reported to be present in over half (53%) of bladder cancer patients [14] and less than one-fifth (18%) of kidney cancer patients [15].

Diagnostic difficulty is therefore a function of both the symptom signature and PPV of symptom(s). Fast-track referral pathways, based on alarm symptoms with high PPVs, will improve early diagnosis of cancers such as bladder cancer, but are less helpful for kidney cancer.

Evaluating Symptoms of Possible Urological Cancer

Visible Haematuria

A systematic review published by Schmidt-Hansen et al. found that visible haematuria has the highest PPV (5.1%) of any symptom for urological cancer in the primary care setting. It is more predictive of bladder than kidney cancer [16], and the predictive value is dependent on age (higher in older/lower in younger patients) and sex (higher in men than women). Visible haematuria is regarded as an alarm symptom for urological cancer [17], with the likelihood that haematuria is due to urological cancer increasing with age [16]. The varying age cut-offs that have been used in the three guidelines described below reflect the acceptable cost-effectiveness thresholds in the various health systems of potential subsequent investigations required to action upon the patients who fulfil these criteria. Clinicians should have a low threshold for referring patients urgently with visible haematuria for further investigations, according to their national/local age thresholds for referrals.

Both the NICE and Scottish guidelines recommend that GPs refer patients presenting with visible haematuria urgently via the fast-track pathway [18, 19]. While the Scottish guidelines advise referring all patients with painless visible haematuria (no age threshold mentioned), NICE guidelines recommend a referral only in those aged 45 and over with these symptoms. The American Urological Association (AUA) recommends that all patients aged 35 and above with visible (and non-visible) haematuria be investigated [20] (Table 1). Following a referral, the typical secondary care investigative pathway usually consists of at least cystoscopy and upper urinary tract imaging [20].

Non-Visible Haematuria

While GPs are reasonably good at considering visible haematuria as an alarm symptom for possible urological cancer, variations in clinical practice exist regarding the investigation of non-visible haematuria. Varying PPVs for cancer between 2.5% and almost 20% have been reported for non-visible haematuria depending on the study population [21], with lower values reported in primary care (about 1.6% [16])—likely explaining the differences in approaches to management of this symptom.

The cancer detection rates in patients with non-visible haematuria differ by whether they are symptomatic or not, with symptomatic patients associated with a higher cancer detection rate (e.g. 9.1% vs 1.5% in a referred population with haematuria in a single institution in Denmark [22]). The approach to managing non-visible haematuria therefore differs by whether these patients also have other symptoms.

The AUA guidelines recommend that all patients aged 35 and over with non-visible haematuria confirmed on urine microscopy (whether symptomatic or not) should undergo cystoscopy and renal tract imaging [20], while the NICE guidelines recommend an urgent referral only in patients aged 60 and over with an additional symptom (dysuria) or raised white cell count on a blood test [18]. A large US study consisting of over 9000 patients aged 65 years and above with non-visible haematuria found that 65% had no further evaluation or referral up to 6 months after presentation [23]. Although a proportion of these non-evaluated cases may be justifiable, it is likely that some may represent potential missed diagnostic opportunities especially in patients of this age group. An additional challenge is the lack of consensus of guidelines on the management of asymptomatic non-visible haematuria, which report varying age thresholds for further diagnostic evaluation [24], likely reflecting the lack of high-quality evidence supporting the management of this patient group.

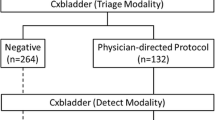

In those with asymptomatic non-visible haematuria, a clinician should also consider the possibility of renal pathology, and provide follow-up advice to patients, as to how and when to reappraise their symptoms, and re-present should primary care tests yield negative results. The AUA suggests that transient or benign causes of non-visible haematuria such as infection, menstruation and recent urological procedures be assessed and treated [20]. Symptomatic patients should be advised to return after antibiotic treatment for their urinary tract infections (UTIs) or benign condition to ensure the resolution of non-visible haematuria. Further investigations should be performed in people with persistent symptomatic non-visible haematuria. Figure 1 shows a practical way of managing non-visible haematuria for a GP working in England, taking into account NICE guidelines and published expert opinion [18, 21]. Future research should also aim to identify the groups of patients who will benefit from active monitoring of their symptoms and signs, and the cost-effectiveness of such approaches.

An adapted approach to managing non-visible haematuria based on NICE [18] (in green) and evidence-based expert opinion [21] (in orange). ACR albumin-to-creatinine ratio, BP blood pressure, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, KUB kidneys ureters bladder, NVH non-visible haematuria, MSU mid-stream urine, UTI urinary tract infection

Non-Haematuria Symptoms and Symptom Combinations

Besides visible haematuria, the PPVs of other clinical features in primary care including non-visible haematuria, UTI, abdominal pain, back pain, dysuria, fatigue, constipation, nausea, loss of appetite and deep vein thrombosis are all well below the 3% NICE threshold for referrals for further investigation [16]. Although these individual symptoms have low PPVs for cancer, combinations of “risks”, including other symptoms, investigations and age have been used to identify patients at relatively high risk of having cancer [14, 15]. For example, the 2015 NICE guideline recommends that patients aged 60 and over with unexplained non-visible haematuria and dysuria should be referred on the fast-track route (> 3% PPV). Similarly, Scottish guidelines recommend an urgent referral in those with visible haematuria and UTI symptoms but sterile urine culture [19]. In the absence of haematuria, NICE also suggested that patients with recurrent or persistent UTIs be considered for a non-urgent referral to a urologist for further investigations [18], as evidence indicates that UTIs may be associated with increased bladder cancer risk [25, 26].

Challenges and Future Directions

Although the evidence regarding PPVs and symptom signature for urological cancers is reasonably well established, we describe below three areas where practical applications of this knowledge can be used to improve early detection of cancer.

Risk Prediction Tools

The low diagnostic yield of single symptoms (except visible haematuria) and relatively broad symptom signature of kidney cancer call for the development of risk stratification strategies to identify patients at higher risk of these cancers. Electronic risk prediction tools, embedded in medical records, could be developed to incorporate socio-demographic and clinical features [27], assisting clinicians in decision-making. Existing evidence suggests that risk assessment tools can be helpful for GPs to consider their referral thresholds and act as a diagnostic aid by prompting them to investigate and actively manage medium- to high-risk patients [28].

Electronic Trigger Tools

Patients, particularly women, are more likely to be diagnosed with benign conditions such as UTIs in the year before being diagnosed with urological cancers [29, 30]. The recurrence and persistence of symptoms may be an indication of a possible underlying malignancy. Electronic trigger tools embedded in existing clinical information systems can be promising when used to identify the patients with recurrent or persistent UTIs who might be at risk of a missed diagnostic opportunity for cancer [31, 32].

Biomarkers, Point-of-Care and Screening Tests for Symptomatic and Asymptomatic Populations

At present, there are no reliable screening tests for bladder and kidney cancer. Urinary biomarkers such as NMP22 have been tested and used to diagnose bladder cancer in symptomatic patients [33], but their use in screening or in the primary care setting is unknown. Similarly, ultrasound is being examined in large multicentre trials to see if they can be a cost-effective screening method for kidney cancer.

Conclusions

We summarise existing evidence and guidelines relating to the management of three common presenting features of possible bladder and kidney cancer—visible haematuria, non-visible haematuria and urinary tract infections. We recommend that clinicians have a low threshold for investigating visible haematuria, which has the highest PPV for urological cancer among all symptoms. We also provide a flowchart detailing a stepwise approach to managing non-visible haematuria, which can be a challenge to manage because of their low PPV for cancer and paucity of high-quality evidence-based guidelines. Patients with persistent or recurrent urinary tract infections should also be considered for non-urgent investigations by a specialist. Future directions for research should look into the development, implementation and evaluation of clinical aids, including risk assessment tools, electronic triggers for prompting/reminding clinicians of necessary follow-up actions and the use of point-of-care tests and biomarkers in the primary care setting.

Change history

24 February 2020

The original article was published with an incorrect license statement.

References

Cancer Research UK. Statistics by cancer type. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type. Accessed 1 Mar 2019.

Smittenaar C, Petersen K, Stewart K, Moitt N. Cancer incidence and mortality projections in the UK until 2035. Br J Cancer. 2016;115(9):1147–55.

National Cancer Intelligence Network. Routes to diagnosis 2006–2015 workbook. http://www.ncin.org.uk/publications/routes_to_diagnosis. Accessed 1 Mar 2019.

Cancer Research UK. Be Clear on Cancer. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/awareness-and-prevention/be-clear-on-cancer. Accessed 1 Mar 2019.

Zhou Y, Abel GA, Hamilton W, et al. Diagnosis of cancer as an emergency: a critical review of current evidence. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(1):45.

Neal R, Tharmanathan P, France B, et al. Is increased time to diagnosis and treatment in symptomatic cancer associated with poorer outomes? Systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2015;112:S92–107.

Cohn JA, Vekhter B, Lyttle C, Steinberg GD, Large MC. Sex disparities in diagnosis of bladder cancer after initial presentation with hematuria: a nationwide claims-based investigation. Cancer. 2014;120(4):555–61.

Hollenbeck BK, Dunn RL, Ye Z, et al. Delays in diagnosis and bladder cancer mortality. Cancer. 2010;116(22):5235–42.

Lyratzopoulos G, Abel GA, McPhail S, Neal RD, Rubin GP. Gender inequalities in the promptness of diagnosis of bladder and renal cancer after symptomatic presentation: evidence from secondary analysis of an English primary care audit survey. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002861.

Lyratzopoulos G, Neal RD, Barbiere JM, Rubin GP, Abel GA. Variation in number of general practitioner consultations before hospital referral for cancer: findings from the 2010 National Cancer Patient Experience Survey in England. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(4):353–65.

Dobruch J, Daneshmand S, Fisch M, et al. Gender and bladder cancer: a collaborative review of etiology, biology, and outcomes. Eur Urol. 2016;69(2):300–10.

Mun D-H, Kimura S, Shariat SF, Abufaraj M. The impact of gender on oncologic outcomes of bladder cancer. Curr Opin Urol. 2019;29(3):279–85.

Koo MM, Hamilton W, Walter FM, Rubin GP, Lyratzopoulos G. Symptom signatures and diagnostic timeliness in cancer patients: a review of current evidence. Neoplasia. 2018;20(2):165–74.

Shephard EA, Stapley S, Neal RD, Rose P, Walter FM, Hamilton WT. Clinical features of bladder cancer in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62(602):e598–604.

Shephard E, Neal R, Rose P, Walter F, Hamilton WT. Clinical features of kidney cancer in primary care: a case-control study using primary care records. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(609):e250–5.

Schmidt-Hansen M, Berendse S, Hamilton W. The association between symptoms and bladder or renal tract cancer in primary care: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2015;65(640):e769–75.

Price SJ, Shephard EA, Stapley SA, Barraclough K, Hamilton WT. Non-visible versus visible haematuria and bladder cancer risk: a study of electronic records in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(626):e584–9.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. NICE guidelines [NG12]—Suspected cancer: recognition and referral. 2015. http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG12/. Accessed 1 Mar 2019.

NHS Scotland. Scottish referral guidelines for suspected cancer. http://www.cancerreferral.scot.nhs.uk/urological-cancers/. Accessed 1 Mar 2019.

American Urological Association. Diagnosis, evaluation and follow-up of asymptomatic microhematuria (AMH) in adults. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/asymptomatic-microhematuria-(2012-reviewed-for-currency-2016). Accessed 1 Mar 2019.

Kelly JD, Fawcett DP, Goldberg LC. Assessment and management of non-visible haematuria in primary care. BMJ 2009;338:a3021. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a3021.

Elmussareh M, Young M, Ordell Sundelin M, Bak-Ipsen CB, Graumann O, Jensen JB. Outcomes of haematuria referrals: two-year data from a single large university hospital in Denmark. Scand J Urol. 2017;51(4):282–9.

Bassett JC, Alvarez J, Koyama T, et al. Gender, race, and variation in the evaluation of microscopic hematuria among Medicare beneficiaries. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(4):440–7.

Linder BJ, Bass EJ, Mostafid H, Boorjian SA. Guideline of guidelines: asymptomatic microscopic haematuria. BJU Int. 2018;121(2):176–83.

Richards KA, Ham S, Cohn JA, Steinberg GD. Urinary tract infection-like symptom is associated with worse bladder cancer outcomes in the Medicare population: implications for sex disparities. Int J Urol. 2016;23(1):42–7.

Akhtar S, Al-Shammari A, Al-Abkal J. Chronic urinary tract infection and bladder carcinoma risk: a meta-analysis of case–control and cohort studies. World J Urol. 2018;36(6):839–48.

Loo RK, Lieberman SF, Slezak JM, et al. Stratifying risk of urinary tract malignant tumors in patients with asymptomatic microscopic hematuria. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(2):129–38.

Hamilton W, Green T, Martins T, Elliott K, Rubin G, Macleod U. Evaluation of risk assessment tools for suspected cancer in general practice: a cohort study. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(606):e30–6.

Aziz A, Madersbacher S, Otto W, et al. Comparative analysis of gender-related differences in symptoms and referral patterns prior to initial diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: a prospective cohort study. Urol Int. 2015;94(1):37–44.

Cohn JA, Vekhter B, Lyttle C, Steinberg GD, Large MC. Sex disparities in diagnosis of bladder cancer after initial presentation with hematuria: a nationwide claims-based investigation. Cancer. 2014;120(4):555–61.

Murphy DR, Wu L, Thomas EJ, Forjuoh SN, Meyer AND, Singh H. Electronic trigger-based intervention to reduce delays in diagnostic evaluation for cancer: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;2061:1301.

Kidney E, Berkman L, Macherianakis A, et al. Preliminary results of a feasibility study of the use of information technology for identification of suspected colorectal cancer in primary care: the CREDIBLE study. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(s1):S70.

Budman LI, Kassouf W, Steinberg JR. Biomarkers for detection and surveillance of bladder cancer. Can Urol Assoc J. 2008;2(3):212.

Acknowledgements

Funding

Yin Zhou is funded by a Wellcome Trust Primary Care Clinician PhD Fellowship (203921/Z/16/Z). This research is linked to the CanTest Collaborative, which is funded by Cancer Research UK [C8640/A23385], of which Fiona M. Walter is Director and Georgios Lyratzopoulos is Associate Director. Garth Funston is funded by the CanTest Collaborative. No article processing charges were received by the journal for the publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Yin Zhou, Garth Funston, Georgios Lyratzopoulos and Fiona M. Walter have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7998233.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Funston, G., Lyratzopoulos, G. et al. Improving the Timely Detection of Bladder and Kidney Cancer in Primary Care. Adv Ther 36, 1778–1785 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-00966-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-00966-x