Abstract

Introduction

Continuous usage of direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) among nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) patients is essential to maintain stroke prevention. We examined switching and discontinuation rates for the three most frequently initiated DOACs in NVAF patients in the USA.

Methods

Patients who initiated apixaban, rivaroxaban, or dabigatran (index event/date) were identified from the Pharmetrics Plus claims database (Jan 1, 2013–Sep 30, 2016, includes patients with commercial and Medicare coverage) and grouped into cohorts by index DOAC. Patients were required to have a diagnosis of NVAF and continuous health plan enrollment for 12 months prior to the index date (baseline period) and at least 3 months during the follow-up period. Drug switching rates to any other DOAC or warfarin and index DOAC discontinuation rate were evaluated separately with descriptive statistics, Kaplan–Meier analysis, and multivariable Cox regression analysis.

Results

Of the NVAF study population (n = 41,864), 37% initiated apixaban (n = 15,352; mean age 62 years), 51% initiated rivaroxaban (n = 21,250; mean age 61 years), and 13% initiated dabigatran (n = 5262; mean age 61 years). During the follow-up period, the unadjusted drug switching rates of patients treated with apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran were 3.6%, 6.3%, and 11.1%, respectively (p < 0.001 across the three cohorts); while the index DOAC discontinuation rates were 52.8%, 60.3%, and 62.9%, respectively (p < 0.001). After we controlled for differences in patient characteristics, patients treated with rivaroxaban (HR 1.8; 95% CI 1.6–2.0; p < 0.001) and dabigatran (HR 3.4; 95% CI 3.0–3.8, p < 0.001) had a significantly greater likelihood for drug switching than patients treated with apixaban. Also, both rivaroxaban (HR 1.1; 95% CI 1.1–1.2, p < 0.001) and dabigatran (HR 1.3; 95% CI 1.2–1.3, p < 0.001) treated patients were more likely to discontinue treatment.

Conclusion

In the real-world setting, patients with NVAF newly treated with apixaban were less likely to switch or discontinue treatment compared to patients treated with rivaroxaban or dabigatran.

Funding

Pfizer and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common heart arrhythmia with an estimated lifetime risk of 1 in 4 [1]. In 2010 in the USA, there were an estimated 5.2 million persons with AF; this number is projected to increase to 12.1 million by 2030 [2]. Nonvalvular AF (NVAF) has long been identified as a significant risk factor for disabling or fatal ischemic stroke and systemic embolism, especially in older individuals, who have up to a fivefold increased risk for stroke compared to the general population [2]. AF carries a significant incremental economic burden, costing the US healthcare system up to $26 billion annually, with the majority of this cost related to hospitalizations [3].

Over the last decade, direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have been developed with the goal of decreasing stroke and bleeding risk without the inconvenience of continuous monitoring and risks associated with the commonly used oral anticoagulant (OAC) warfarin [4]. The FDA-approved DOACs include apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and edoxaban, all of which have demonstrated similar or superior reduction in stroke risk when compared to warfarin in clinical trials, with all being associated with a significant reduction in the risk of hemorrhagic stroke [5,6,7,8]. Many studies of apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran vs. warfarin conducted in real-world settings have confirmed the effectiveness and safety profiles of these DOACs for stroke prevention for NVAF patients [9,10,11,12,13,14].

As the utilization of DOACs for stroke prevention in patients with NVAF is becoming increasingly widespread over more diverse patient populations and the fact that continuous usage of DOACs is essential to maintain stroke prevention, it is important to understand their usage patterns in the real-world setting. Therefore, we examined switching and discontinuation rates for the three most frequently initiated DOACs, apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran, in NVAF patients in the USA.

Methods

This study was a retrospective database analysis using data from the Pharmetrics Plus database between January 1, 2012 and December 31, 2016. The Pharmetrics Plus database is an integrated source of managed care medical and pharmacy claims that includes enrollees of all age groups and encompasses more than 150 million US patients with commercial health plans and Medicare coverage. The medical claims data includes information on diagnostic and therapeutic services provided in the inpatient and outpatient settings. The pharmacy claims data contains information on prescription drugs dispensed (i.e., characteristics of the drug dispensed, such as the National Drug Code, quantity, and days of supply). The medical and pharmacy claims information includes the dates of service and the amounts allowed (for maximum payment) for the service/drug. Demographic characteristics and periods of eligibility for each patient are additionally included in the data sets. In compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), the database utilized for this retrospective claims database analysis consists of fully de-identified data sets, with synthetic identifiers applied to patient-level and provider-level data to protect the identities of both the patients and data contributors.

Study Population

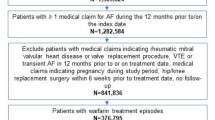

Adult patients (at least 18 years old) who initiated apixaban, rivaroxaban, or dabigatran (index event/date) were identified from the Pharmetrics Plus claims database between January 1, 2013 and September 30, 2016. The date that patients initiated the DOAC treatment was designated as the index date. Patients were required to have a primary or secondary International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis code of 427.31 or the corresponding 10th Revision (ICD-10) code I48.x, indicating AF in the 12 months prior to or on the index date. Patients were additionally required to have continuous health plan enrollment for 12 months prior to the index date (baseline period) and for at least 3 months after the index date (follow-up period). The patient follow-up period ended at the earliest of the following dates: the end of DOAC treatment date, the health plan disenrollment date, or the end of the study period (December 31, 2016). Patients were excluded from the study population if during the 12-month baseline period they had a medical claim indicative of valvular heart disease, kidney disease, venous thromboembolism, or reversible AF; if they had hip or knee surgery within a 6-week period prior to the index date; or if they had a claim indicating pregnancy at any time during the study period. Patients were also excluded from the study population if they had a pharmacy claim for apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, edoxaban, or warfarin during the 12-month baseline period or if they had prescription claims of more than one type of OAC on the index date.

Patients were grouped into cohorts depending on which DOAC they received on the index date (apixaban, rivaroxaban, or dabigatran). Patients initiating edoxaban were not analyzed in this study because of its late entry into the US market and hence small patient sample size.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Patient characteristics, including age, gender, US geographic region, and health plan type and clinical characteristics, including Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) score which is indicative of general comorbidity level, CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores which are indicative of stroke risk, HAS-BLED score which is indicative of major bleeding risk, prior bleeding in baseline, prior stroke in baseline, baseline co-medications, and DOAC dosage level (standard/low) were evaluated during the 12-month baseline period or on the index date.

Drug Switching and Discontinuation

The proportions of patients that switched to a different OAC drug or discontinued their index DOAC in the follow-up periods were evaluated for each study cohort. Patients with another non-index OAC prescription claim that occurred prior to the index DOAC discontinuation date or the end of study period, whichever was earlier, were considered to have switched their index DOAC. Among switchers, the proportions of patients that switched to either another DOAC or warfarin were examined. DOAC discontinuation was defined as having a gap of more than 30 days in days supply of index DOAC drug prescription. The term “discontinuation” is used here to describe patients with interruption in therapy and may not indicate permanent drug discontinuation. However, on the basis of recently published literature, drug discontinuation is often the term used to describe such interruption of therapy [13, 15].

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were utilized to describe and compare patient demographics, clinical characteristics, switching rates, and discontinuation rates of the study cohorts. ANOVA tests and chi-square tests were used to detect statistically significant differences in continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to summarize times to DOAC switching and discontinuation after initiating index DOACs. Multivariable Cox regression analyses were used to determine whether the index DOAC (rivaroxaban or dabigatran, separately vs. apixaban) impacted the likelihood for switching to another OAC or drug discontinuation. Covariates controlled for in the Cox regression analyses included gender, US geographic region, health plan type, CCI score group, CHA2DS2-VASc score group, HAS-BLED score group, prior bleeding in baseline, prior stroke in baseline stroke, select baseline co-medications, and index DOAC dosage level (low/standard). An alpha value of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS 9.4.

Results

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Cohorts

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics of the study cohorts are shown in Table 1. Of the NVAF study population (n = 41,864), 37% initiated apixaban (n = 15,352; mean age 62 years; 31.1% female), 51% initiated rivaroxaban (n = 21,250; mean age 61 years; 27.9% female), and 13% initiated dabigatran (n = 5262; mean age 61 years; 26.2% female). Mean CCI score (1.5 vs. 1.4 vs. 1.4, p < 0.001), CHA2DS2-VASc score (2.4 vs. 2.1 vs. 2.2, p < 0.001), and HAS-BLED score (2.6 vs. 2.5 vs. 2.5, p < 0.001) were highest for the apixaban cohort. Prior to starting treatment, more patients who initiated apixaban had bleeding (13.4% vs. 11.9% vs. 11.3%, p < 0.001) and stroke (6.6% vs. 5.1% vs. 5.9%, p < 0.001) than patients who initiated either rivaroxaban or dabigatran. The majority of patients initiated their index DOAC at a standard dosage, while 6.2% of apixaban treated patients, 9.5% of rivaroxaban treated patients, and 5.0% of dabigatran treated patients initiated a low DOAC dosage level (p < 0.001). The mean duration of follow-up was 8.0 months for patients treated with apixaban, 9.0 months for patients treated with rivaroxaban, and 9.1 months for patients treated with dabigatran, likely reflecting the later commercial availability of apixaban in the USA.

Unadjusted Drug Switching and Discontinuation Rates

During the follow-up period, the unadjusted drug switching rates of patients treated with apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran were 3.6%, 6.3%, and 11.1%, respectively (p < 0.001 across the three cohorts); while the index DOAC discontinuation rates were 52.8%, 60.3%, and 62.9%, respectively (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Of the patients who switched from apixaban, the most frequent OAC switched to was warfarin (48.7%), followed by rivaroxaban (38.1%) (Table 2). Of the patients who switched from rivaroxaban, the most frequent OAC switched to was apixaban (44.3%), followed by warfarin (43.8%) (Table 2). Of the patients who switched from dabigatran, the most frequent OAC switched to was rivaroxaban (40.8%), followed by apixaban (30.0%) (Table 2).

Kaplan–Meier analysis of times to switching to another OAC and index DOAC drug discontinuation for study cohorts are illustrated in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively.

Multivariable Cox Regression Analyses: Likelihoods for Drug Switching and Discontinuation

After we controlled for differences in patient characteristics, patients treated with rivaroxaban (hazard ratio (HR) 1.78; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.61–1.96; p < 0.001) and dabigatran (HR 3.40; 95% CI 3.03–3.82, p < 0.001) had significantly greater likelihoods for drug switching than patients treated with apixaban (Fig. 4a). Also, both rivaroxaban (HR 1.12; 95% CI 1.09–1.15, p < 0.001) and dabigatran (HR 1.29; 95% CI 1.23–1.34, p < 0.001) treated patients were significantly more likely to discontinue DOAC treatment compared to patients treated with apixaban (Fig. 4b).

Discussion

In this analysis of nearly 42,000 NVAF patients (identified from January, 2013 to September, 2016, including both patients with commercial insurance and Medicare coverage) who newly initiated DOACs, 37% initiated apixaban, 51% initiated rivaroxaban, and 13% initiated dabigatran. Our findings were that, after we adjusted for differences in patient characteristics, NVAF patients who received apixaban were significantly less likely to switch or discontinue treatment compared to patients who received either rivaroxaban or dabigatran. In this study, approximately 21% of patients who initiated DOACs switched to another OAC (apixaban 3.6%; rivaroxaban 6.3%; dabigatran 11.1%). The overall DOAC switching rate was similar to that reported by Manzoor et al. who found that, among 34,022 OAC-naïve NVAF patients identified from the MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Database during 2009–2013, 19.4% of patients who initiated DOACs switched to another OAC [16]. In the study of Manzoor et al., the NVAF patients who switched from their index DOAC switched to warfarin or another DOAC fairly equally [16]. Among our study population, slightly more NVAF patients who switched from apixaban switched to another DOAC than to warfarin (51.4% vs. 48.7%); of those who switched from rivaroxaban (56.3% vs. 43.8%) and dabigatran (71.1% vs. 28.8%), more patients switched to another DOAC than to warfarin. Because of the limitations of the claims database used for this study, we were unable to establish reasons for switching OAC treatment and further research is warranted on this topic.

In an updated analysis by Brown et al. [17], the switching rate observed among 15,341 NVAF patients identified between 2013 and 2014 from MarketScan data was higher than observed in our study and also than that observed in the study by Manzoor et al. [16]. In this particular study, of the patients treated with dabigatran, apixaban, and rivaroxaban, 18.8%, 10.5%, and 9.5%, respectively, switched within 9 months of starting DOAC treatment [16]. However, compared to that observed in our study, the DOAC discontinuation rate (gap of at least 30 days) was lower, ranging between 11.9% and 15.9% after 9 months [16]. The study cohorts of Brown et al. were older with a mean age that ranged between 68 and 74 years old and they were at higher stroke risk, which may indicate that older NVAF patients with higher stroke risk are more likely to switch treatment than discontinue DOAC treatment [16]. As prescribing trends change for OACs, it will be important to continue to monitor such switching and discontinuation trends as this information may be useful for healthcare decision-makers and payers for optimizing OAC treatment choices for particular patient groups.

In the current study, the unadjusted discontinuation rates of NVAF patients who initiated apixaban, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran were 52.8%, 60.3%, and 62.9%, respectively, and were generally consistent with the findings of Lip et al., who reported cumulative discontinuation rates after 1 year of 50.5% for apixaban, 57.8% for rivaroxaban, and 64.7% for dabigatran among NVAF patients (n = 29,900 identified from MarketScan data; mean ages 66.5–68.5 years) who newly initiated DOAC treatment [15]. In both the Lip et al. study and our study, discontinuation was defined as having a gap of more than 30 days in prescriptions and may be indicative of patients with an interruption in therapy and not permanent drug discontinuation. Our regression adjusted hazard rates for discontinuation of rivaroxaban vs. apixaban (HR 1.1, p < 0.001) and dabigatran vs. apixaban (1.3, p < 0.001) were also directionally consistent with those of Lip et al., who reported 1.2-fold and 1.5-fold increased risk for discontinuation for rivaroxaban and dabigatran users, respectively, compared to apixaban users [15].

McHorney et al. conducted a study of NVAF patients identified from the IMS Health claims database during July 2012 to June 2015 [18]. They reported persistence (i.e., no gap of more than 30 days between end of days of supply and the next fill start date) rates at 9 months after NVAF patients initiated DOACs of 68.1% for apixaban, 69.3% for rivaroxaban, and 57.8% for dabigatran [18]. These findings may be presumed to indicate lower discontinuation rates of DOACs among their study population than observed in our study population [18]. After adjusting for patient differences, the findings of McHorney et al. were that NVAF patients who initiated rivaroxaban vs. those who were treated with apixaban and dabigatran were more likely to be persistent and adherent [proportion of days covered (PDC) at least 0.80] to treatment [18]. Noted differences in the study population of McHorney et al. vs. our study population include that NVAF patients were older and they had greater comorbidity with higher stroke risk [18]. Furthermore, unlike in our study in which patients were excluded if they had prior usage of OACs in the 12-month baseline period, between 20% and 35% of the cohorts in the study by McHorney et al. had prior usage of OACs other than their index OAC [18]. A second study by Manzoor et al. looked at persistence and adherence to DOACs when NVAF patients were stratified by whether they were naïve or experienced with OAC usage [19]. In this study of 66,090 patients identified from MarketScan data, those who were naïve to OAC treatment compared to those who were experienced had lower persistence and suboptimal adherence to treatment [19]. This could be related to potentially longer duration and greater severity of NVAF in OAC-experienced patients than OAC-naïve patients. Thus, since our patient population was entirely OAC naïve (at least in the 12-month baseline period), they might be expected to have higher discontinuation rates than observed by McHorney et al. and the findings between the DOACs may differ as well [18].

A large retrospective claims database analysis by Yao et al. of 64,661 patients with AF (identified from Optum Labs Data Warehouse between November 2010 and the end of 2014) who initiated apixaban (16.4% of study population), rivaroxaban (39.2%), dabigatran (10.3%), or warfarin (34.1%) reported that approximately 47.5% of the patients treated with DOACs were adherent (PDC at least 80%) to treatment, compared with 40.2% of warfarin-treated patients [20]. The proportion of patients adherent to DOAC treatment was similar to that observed by Brown et al., which was also less than half regardless of the DOAC that was initiated [17]. In the study by Yao et al., patients treated with apixaban had the highest unadjusted rate of adherence at 61.9%, followed by patients treated with rivaroxaban (50.5%) and dabigatran (38.5%) [20]. As observed in prior studies [21,22,23], Yao et al. found that patients with a high stroke risk who were nonadherent to DOAC treatment were at significantly increased risk for stroke compared to adherent patients [20]. Moreover, a recent analysis of participants in the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial found that an interruption of more than 3 days in anticoagulation therapy (edoxaban or warfarin) was associated with a considerable increase in the risk for major cardiac and cerebrovascular events in the 30 days following therapy interruption [24]. Alongside the high discontinuation rates observed in our study and that observed by Lip et al., the findings of Yao et al. [20] highlight that adherence to anticoagulation treatment is generally poor in routine clinical practice in the USA. Additionally, under the relatively currently used OAC management practices, adherence is only found to be modestly improved with DOACs vs. warfarin treatment [20]. Thus, persistence and continuous adherence to OAC treatment remain a challenge, suggesting more routine outpatient follow-up of NVAF patients is needed to better inform NVAF patients of the importance of adherence to treatment for maintaining stroke prevention and also to address barriers to OAC continuation. The importance of medication adherence is further emphasized in that it is being used as a quality metric for providers and health plans, as well as for making formulary decisions and determining prescribing practices [17, 25, 26].

Limitations

In this observational study, we found that NVAF patients who initiated apixaban have slightly higher stroke and bleeding risks, according to CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores and prior stroke and bleeding, compared to patients who initiated rivaroxaban and dabigatran. Although these differences were relatively minor, this is a trend that has been observed in other real-world studies [27, 28]. We did control for these particular patient differences in the Cox regression analyses, and thus the adjusted results remain supportive of our study’s conclusion in that the risks for switching and discontinuation differ among the DOAC study cohorts. However, some unrecognized confounders may still exist, such as the potential differences in choosing a specific DOAC (e.g., a once-daily drug being chosen for less compliant patients, or certain low-risk AF patients only planned to be on anticoagulation for a brief period, etc.). Other such evaluations using other data sources may be needed to further validate the findings of this study.

There are other limitations to this retrospective claims database analysis. As mentioned we were unable to establish reasons for switching OAC treatment and further research is warranted on this topic, especially in regard to the influence of dosage levels. Although claims data are valuable for examination of healthcare outcomes, treatment patterns, healthcare resource utilization and costs, the available data have inherent limitations since the claims are collected for the purpose of payment and not research. First, a claim for a filled prescription does not necessarily mean the medication was taken as prescribed. Second, over-the-counter medications and samples by the physician are not recorded in claims data. Third, diagnosis codes on medical claims are subject to errors and may not absolutely indicate the presence of disease in the absence of other clinical information. The PharMetrics Plus database contains information from millions of patients across the USA; however, it is possible that it may not be representative of the entire US population of NVAF patients as it is primarily composed of claims from commercial health plans. Lastly, billing and coding errors and missing data could potentially have occurred on database records, and unmeasured confounders may not be captured in the data source. Further study of switching and discontinuation rates of NVAF patients treated with the different DOACs with longer follow-up and from other data sources is warranted.

Conclusions

According to this study conducted in the real-world setting in the USA, patients with NVAF treated with apixaban were less likely to switch or discontinue treatment compared to patients treated with rivaroxaban or dabigatran. The findings of this study may be useful for healthcare decision-makers and patients to understand the patterns of use of the different oral anticoagulant treatment options, which is an initial necessary step in considering factors that will potentially lead to better treatment satisfaction and improved patient outcomes.

References

Ball J, Carrington MJ, McMurray JJ, Stewart S. Atrial fibrillation: profile and burden of an evolving epidemic in the 21st century. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:1807–24.

Colilla S, Crow A, Petkun W, Singer DE, Simon T, Liu X. Estimates of current and future incidence and prevalence of atrial fibrillation in the U.S. adult population. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:1142–7.

Kim MH, Johnston SS, Chu BC, Dalal MR, Schulman KL. Estimation of total incremental health care costs in patients with atrial fibrillation in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4:313–20.

Amin A, Marrs JC. Direct oral anticoagulants for the management of thromboembolic disorders: the importance of adherence and persistence in achieving beneficial outcomes. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2016;22:605–16.

Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJ, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:981–92.

Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:883–91.

Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139–51.

Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2093–104.

Ntaios G, Papavasileiou V, Makaritsis K, Vemmos K, Michel P, Lip GYH. Real-world setting comparison of nonvitamin-K antagonist oral anticoagulants versus vitamin-K antagonists for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2017;48:2494–503.

Lin J, Trocio J, Gupta K, et al. Major bleeding risk and healthcare economic outcomes of non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients newly-initiated with oral anticoagulant therapy in the real-world setting. J Med Econ. 2017;20:952–61.

Deitelzweig S, Luo X, Gupta K, et al. Comparison of effectiveness and safety of treatment with apixaban vs. other oral anticoagulants among elderly nonvalvular atrial fibrillation patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33:1745–54.

Adeboyeje G, Sylwestrzak G, Barron JJ, et al. Major bleeding risk during anticoagulation with warfarin, dabigatran, apixaban, or rivaroxaban in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23:968–78.

Yao X, Abraham NS, Sanaralingham LR, et al. Effectiveness and safety of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003725.

Lip GY, Keshishian A, Kamble S, et al. Real-world comparison of major bleeding risk among non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients initiated on apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or warfarin. A propensity score matched analysis. Thromb Haemost. 2016;116:975–86.

Lip GYH, Pan X, Kamble S, et al. Discontinuation risk comparison among ‘real-world’ newly anticoagulated atrial fibrillation patients: apixaban, warfarin, dabigatran, or rivaroxaban. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0195950.

Manzoor BS, Walton SM, Sharp LK, Galanter WL, Lee TA, Nutescu EA. High number of newly initiated direct oral anticoagulant users switch to alternate anticoagulant therapy. J Thromb Thombolysis. 2017;44:435–41.

Brown JD, Shewale AR, Talbert JC. Adherence to rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and apixaban for stroke prevention for newly diagnosed and treatment-naïve atrial fibrillation. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23:958–67.

McHorney CA, Ashton V, Laliberté F, et al. Adherence to rivaroxaban compared with other oral anticoagulant agents among patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23:980–8.

Manzoor BS, Lee TA, Sharp LK, Walton SM, Galanter WL, Nutescu EA. Real-world adherence and persistence with direct oral anticoagulants in adults with atrial fibrillation. Pharmacotherapy. 2017;37:1221–30.

Yao X, Abraham NS, Alexander GC, et al. Effect of adherence to oral anticoagulants on risk of stroke and major bleeding among patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003074.

Schulman S, Shortt B, Robinson M, Eikelboom J. Adherence to anticoagulant treatment with dabigatran in a real-world setting. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1295–9.

Patel MR, Hellkamp AS, Lokhnygina Y, et al. Outcomes of discontinuing rivaroxaban compared with warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: analysis from the ROCKET AF trial (rivaroxaban once-daily, oral, direct factor Xa inhibition compared with vitamin K antagonism for prevention of stroke and embolism trial in atrial fibrillation). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:651–8.

Sherwood MW, Douketis JD, Patel MR, et al. Outcomes of temporary interruption of rivaroxaban compared with warfarin in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation: results from ROCKET AF. Circulation. 2014;129:1850–9.

Cavallari I, Ruff CT, Nordio F, et al. Clinical events after interruption of anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation: an analysis from the ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48 trial. Int J Cardiol. 2018;15(257):102–7.

Pharmacy Quality Alliance. PQA performance measures. http://pqaalliance.org/measures/default.asp. Accessed 5 June 2018.

Leslie RS, Gilmer T, Natarajan L, Hovell M. A multichannel medication adherence intervention influences patient and prescriber behavior. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22:526–38.

Lip GY, Pan X, Kamble S, et al. Major bleeding risk among non-valvular atrial fibrillation patients initiated on apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban or warfarin: a “real-world” observational study in the United States. Int J Clin Pract. 2016;70:752–63.

Deitelzweig S, Bruno A, Trocio J, et al. An early evaluation of bleeding-related hospital readmissions among hospitalized patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation treated with direct oral anticoagulants. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32:573–82.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study, article processing charges, and the open access fee were funded by Pfizer and Bristol-Myers Squibb. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Christine L Baker is an employee and stockholder of Pfizer. Amol D. Dhamane is an employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb. Jack Mardekian is an employee and stockholder of Pfizer. Oluwaseyi Dina is an employee and stockholder of Pfizer. Cristina Russ is an employee and stockholder of Pfizer. Lisa Rosenblatt is an employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb. Melissa Lingohr-Smith is an employee of Novosys Health, which has received research funds from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer in connection with conducting this study and development of this manuscript. Brandy Menges is an employee of Novosys Health, which has received research funds from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer in connection with conducting this study and development of this manuscript. Jay Lin is an employee of Novosys Health, which has received research funds from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Pfizer in connection with conducting this study and development of this manuscript. Anagha Nadkarni is an employee of Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

In compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), the database utilized for this retrospective claims database analysis consists of fully de-identified data sets, with synthetic identifiers applied to patient-level and provider-level data to protect the identities of both the patients and data contributors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced digital features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7306469.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Baker, C.L., Dhamane, A.D., Mardekian, J. et al. Comparison of Drug Switching and Discontinuation Rates in Patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation Treated with Direct Oral Anticoagulants in the United States. Adv Ther 36, 162–174 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0840-8

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0840-8