Abstract

Introduction

Recent developments in the care of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis have the potential to improve survival rates. Population-based estimates of the current disease burden are needed to evaluate the future impact of newly approved therapies. The objective of this study is to describe incidence, prevalence, and survival of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients in the UK.

Methods

Between 2000 and 2012, a patient cohort (N = 9,748,108), identified from Clinical Practice Research Datalink primary care data, was used to identify incident and prevalent cases of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis–clinical syndrome. Incident cases were followed up to identify deaths. Poisson and Cox regressions were used to calculate incidence rate ratios (IRR) and hazard ratios for mortality, respectively. Adjustments were made for age, gender, and strategic health authority. Survival from diagnosis was estimated using Kaplan–Meier analysis.

Results

In total 1491 and 4527 incident cases were identified using narrow and broad idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis–clinical syndrome definitions, respectively. Incidence and prevalence increased during the study. Compared with 2000, a near 80% increase in incidence was observed by 2012 [IRR 1.78 (95% CI 1.50–2.11; broad definition)], despite an observed decrease using the narrow definition [0.50 (0.38–0.65)]. Median survival was 3.0 years (95% CI 2.8–3.1) and 2.7 years (95% CI 2.5–3.0) in broad (n = 2168) and narrow case sets (n = 996), respectively. No significant changes in survival were observed.

Conclusions

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis incidence rates have increased since 2000 and survival remains poor. These results provide a benchmark against which the effects of future treatment changes can be measured.

Funding

InterMune UK and Ireland (now part of F. Hoffman La Roche).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic, progressive fibrotic interstitial lung disease (ILD) of unknown etiology. The disease occurs predominantly in middle-aged and elderly adults, is more frequent in men, and has been linked with cigarette smoking and occupational exposure [1, 2]. Prognosis for patients with IPF is poor, with median survival estimated to be around only 3–4 years [3,4,5,6,7]. Historically, treatment options for patients with IPF have been limited; however, the UK has seen a number of important developments in the treatment of IPF, which it is hoped will translate into improved patient outcomes. These include the development of ILD specialist services [8]; the licensing and reimbursement approval of antifibrotic therapy, firstly pirfenidone in 2013 and nintedanib in 2015 [9, 10]; and publication of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on the diagnosis and management of suspected IPF [11]. If the impact of these important developments in IPF care is to be measured, it is vital that the underlying IPF disease burden is understood. Moreover, the limited available data on the epidemiology of IPF, both in the UK and in the USA [6, 12], suggest that the incidence [4, 5] and mortality [5, 13, 14] rates, as well as hospitalizations [15], for IPF are increasing. Establishing robust estimates of the underlying and secular trends in the epidemiological burden of IPF is therefore of increasing public health significance.

Methods

We carried out a population-based study using data from 2000 to 2012, which aimed to describe the incidence, prevalence, and survival of patients with IPF in the UK, both overall and stratified by calendar year, age, gender, and strategic health authority. We use the term IPF–clinical syndrome (IPF–CS) to describe patients with IPF in our study in order to reflect the imprecision of current coding terms. Owing to the relatively recent introduction of recommended standard diagnostic criteria for IPF [16], and the potential for variability in diagnostic coding, we used both broad and narrow definitions for IPF–CS to explore the impact of coding specificity on the chosen outcome measures.

Data Source

Data were obtained from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) GOLD primary care database (formerly the General Practice Research Database, GPRD). The CPRD is a research and data services provider in the UK, which brings together data from across the UK National Health Service and is jointly funded by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) and the National Institute for Health Research [17]. CPRD GOLD is one of the largest computerized databases of anonymized and longitudinal electronic medical records in the world. At the time of analysis, data were held for approximately 14 million patients, around 5.4 million of whom were alive and registered in 660 contributing general practices across the UK. The data recorded include information on patient demographics, clinical events and diagnoses, details of specialist referrals, hospital admissions, results of laboratory tests, and prescriptions issued. Clinical events and diagnoses are recorded via Read codes [18], and practices are assigned an “up-to-standard” date, which indicates when the data recorded by that practice met pre-specified completeness criteria. Data in CPRD GOLD are broadly representative of the UK population [19] and the validity of the recorded clinical data is considered to be high [20]. The database has also been validated previously for use in respiratory epidemiology [21]. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the CPRD Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (reference number 13_083).

Study Population and Follow-up to Identify Cases of IPF–CS

The study population comprised all patients registered for at least 1 day in practices contributing data deemed “up-to-standard” by CPRD GOLD between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2012 (N = 9,748,108). Patients were followed from their index date until the earliest of the following: date of death, date of transfer out of the practice, or date of last practice data collection. Prevalent cases of IPF–CS were identified on the basis of the presence of a relevant Read code using our broad or narrow definition of IPF–CS. Read codes included in our narrow IPF–CS case definition were H563.00 (Idiopathic fibrosing alveolitis), H563.12 (Cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis), H563z00 (Idiopathic fibrosing alveolitis NOS), H563300 (Usual interstitial pneumonitis), and H563.13 (Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis). Our broad IPF–CS definition included the following three additional Read codes: H563100 (Diffuse pulmonary fibrosis), H563200 (Pulmonary fibrosis), and H563.11 (Hamman–Rich syndrome). Patients with Read codes for connective tissue disease, extrinsic allergic alveolitis, sarcoidosis, pneumoconiosis, or asbestosis (Table S1) at any time in their medical records were not included as cases. Incident cases of IPF–CS were identified by applying the following eligibility criteria to the prevalent cases: at least 1 year of registration with their general practitioner, at least 1 year of up-to-standard data in their patient records before the index date, and no Read code for IPF–CS prior to the start of the study period (1 January 2000).

Statistical Analysis

Incidence and prevalence of IPF–CS per 100,000 patient-years were estimated along with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated using the Poisson distribution. Incidence rates were calculated by dividing the number of incident cases by the total person-time contribution, and were calculated both overall and stratified by calendar year, gender, 5-year age group, and strategic health authority. Poisson regression modelling was used to estimate annual incidence rate ratios (IRRs), controlling for age, sex, and strategic health authority. Multiplicative interaction terms were applied to test for potential effect modification by age and sex. Point prevalence of IPF–CS was calculated for each calendar year in the study period. The numerator was the number of patients with a specified Read code for IPF–CS prior to the midpoint of the year of interest, and the denominator was the number of patients in the study population at the midpoint of the year of interest. Prevalence ratios for 2012 were additionally stratified by age group, gender, and strategic health authority.

Life table analysis was carried out to estimate cumulative mortality (with 95% CIs) at 48 weeks, 52 weeks, 60 weeks, 72 weeks, 3 years, 5 years, 10 years, and more than 10 years after incident diagnosis. Survival was analyzed using Kaplan–Meier methods, both overall and stratified by year of diagnosis, gender, 5-year age group, and strategic health authority. Cox regression analysis was performed to calculate hazard ratios adjusted for all other covariates, and to test for interactions between mortality rates and year of diagnosis, age group, gender, and strategic health authority. The following reference categories were used in these analyses, respectively: (1) patients diagnosed in 2000; (2) patients aged 65–69; (3) male patients; (4) patients based in the North West Strategic Health Authority. Patients were censored in the Kaplan–Meier and Cox regression analyses according to the date they left the practice or the last date that the practice contributed data to CPRD prior to analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article reports a population-based cohort study and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

Incidence and Prevalence of IPF–CS

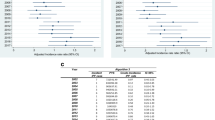

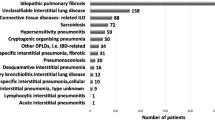

The total number of incident cases of IPF–CS identified between 2000 and 2012 was 1491 using our narrow case definition, and 4527 using our broad case definition. These cases were identified over a total follow-up period of 52,355,644 and 52,341,029 years, respectively. Overall and stratified incidence rates of IPF–CS and IRRs are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. The overall incidence rate per 100,000 patient-years was 2.85 (95% CI 2.71–3.00) using the narrow case definition and 8.65 (8.40–8.90) for the broad case definition. Incidence of IPF–CS increased with age, was more common in male patients than female patients, and varied across regions (as assessed by strategic health authority); being highest in the North West region and Northern Ireland, and lowest in the South East. When using a broad IPF–CS case definition, mutually adjusted IRRs significantly increased over the study period. Compared with the year 2000, a 78% increase in the incidence of IPF–CS was observed in 2012 (IRR 1.78, 95% CI 1.50–2.11). No statistically significant interactions (0.55 < p < 0.74) were observed to suggest the annual increase in incidence varied by age or gender for either IPF–CS definition. Annual prevalence is shown in Fig. 3. When the broad case definition was used, prevalence of IPF–CS approximately doubled over the study period; starting at 19.94 per 100,000 patients (95% CI 18.48–21.47) in 2000 and rising to 38.82 per 100,000 patients (95% CI 37.04–40.66) in 2012. Prevalence in 2012 was higher in male patients, increased with age, and varied across strategic health authority, with highest rates in Scotland and lowest rates in the South East Coast (Fig. 3).

Adjusted incidence rate ratios of IPF–CS stratified by calendar year using a narrow definition and b broad definition. CPRD, Clinical Practice Research Datalink; IPF–CS, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis clinical syndrome. All incidence rate ratios are mutually adjusted for other variables: gender, age group, and strategic health authority

Prevalence rates of IPF–CS stratified by a calendar year, b gender, c age, and d strategic health authority. CPRD, Clinical Practice Research Datalink; IPF–CS, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis clinical syndrome; Yorks, Yorkshire. “[a]” For this analysis the lower age groups (0–39 and 40–44) and two regions (Yorkshire & The Humber and North East) have been combined in line with CPRD policy on low cell counts

Mortality and Survival of Patients with IPF–CS

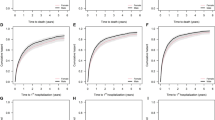

Among incident cases, a total of 2618 and 996 deaths occurred over 11,468 and 4167 years of follow-up from diagnosis in broad and narrow case sets, respectively. Similar patterns of survival were observed with both narrow and broad case definitions (Table 1). Median survival was 3.0 years (95% CI 2.80–3.10) in the broad case group and 2.7 years (95% CI 2.5–3.0) in the narrow case group. Half of patients were alive at 3 years following IPF–CS diagnosis using our broad case definition; 5- and 10-year survival rates were 34% and 19%, respectively. There was no statistically significant survival difference between the broad and narrow case groups, log rank test p = 0.06 (Fig. 4a). There was no statistically significant difference in the survival function by year of diagnosis, log rank test p = 0.17 (broad case definition; Fig. 4b). Models adjusted for demographic variables show that patients diagnosed in 2000 had a higher mortality rate than patients diagnosed in later years (Table 2). However, there is no clear evidence of improvement over time. There was no statistically significant interaction between age and gender following further adjustments (0.07 < p < 0.75).

Discussion

Our large population-based study provides national estimates of the epidemiological burden of IPF in the UK. We did not observe any improvements in survival from diagnosis in patients with IPF–CS over our relatively recent study period (2000–2012). Overall, median survival was found to be 3 years, consistent with rates from previous studies [3, 5] and similar, albeit slightly lower, than that reported by other groups [4, 6, 7]. Navaratnam et al. [5] found that median survival did not change significantly in the UK between 2000 and 2008 using data from The Health Improvement Network (THIN), a primary care database similar to CPRD GOLD. They also reported 5-year survival to be 37%, similar to our value of 34%. Gribbin et al. [4] also investigated mortality of IPF using data from THIN, and reported a 5-year survival rate of 43% over their earlier study period.

When a broad case definition was used, the incidence of IPF–CS increased over time and was found to have risen almost 80% over the course of our study period. This trend of rising incidence is in line with reports from previous studies carried out in the UK using data from primary care [4, 5] and hospital admissions [15]. However, when a narrow case definition was used, an overall decrease in incidence over time was observed. This observation is likely due to changes in the availability of Read codes and recording practices over time. Alternatively, this contrasting trend could be explained by the fact that the overall number of incident cases recorded using the narrow definition is considerably lower than those recorded using the broad definition (1491 and 4527 cases, respectively). There is also a possibility that the diagnostic precision used to distinguish IPF from other types of fibrotic lung disease may have increased over the course of the study period.

We found the incidence of IPF–CS to increase with age and to be higher in male patients, consistent with other reports from the UK and the USA [4,5,6, 22], but found no evidence that the increase in incidence over time was restricted to, or significantly varied by, age group or gender. Findings from others regarding such age and gender effects have been mixed [4, 5, 15]. Our estimates of IPF–CS occurrence and survival were adjusted by age group, sex, and health authority, thus suggesting that the observed increase in incidence and survival is unlikely due to demographic changes in the UK population over time. Other explanations should nevertheless be considered. For instance, it is possible that changes in disease ascertainment and recording of IPF–CS could explain some of the observed rise in incidence. Given that improvements in ascertainment should result in the detection of milder cases, such an explanation is compatible with the changing, albeit inconsistent, survival found using both narrow and broad case definitions. Furthermore, the widely heralded publication of international evidence-based guidelines on the diagnosis and management of IPF in 2011 [23] may explain the slightly greater increase in incidence observed in 2012 due to heightened physician awareness, as might the approval in Europe of pirfenidone in March 2011.

We found regional variation in the incidence of IPF–CS across the UK, with highest rates in the North West and Northern Ireland, and lowest rate in the South East (using the broad case definition), consistent with findings by Navaratnam et al. [5]. In their earlier study period, Gribbin et al. [4] also found rates to be lowest in the South East, but high rates were reported for Scotland in addition to the North West. This regional variation may reflect geographical differences in environmental and occupational risks and is likely to have important implications for national resource utilization. Our study also highlights the impact of using different diagnostic codes for IPF on estimates of incidence and prevalence. The observed similarity in patterns of survival when using either narrow or broad case definitions suggests that both sets of Read codes capture a similar range of cases across disease severity. The similarity of outcomes seen in both groups, when compared to well-defined cohorts of patients with IPF identified through tertiary centers, suggests that the chosen diagnostic codes are successfully identifying patients with disease conforming to the internationally accepted criteria for a diagnosis of IPF.

Our study has several strengths. The large size of the CPRD cohort provided a representative snapshot of the UK population and the long study period enabled ascertainment of precise estimates of disease occurrence, mortality, and temporal change. The use of the CPRD GOLD database enabled analysis of the large dataset required to attempt to estimate the epidemiological burden of IPF; however, we recognize that the main potential weakness of our study concerns the validity of the IPF diagnosis.

Case ascertainment was based on diagnostic coding used by general practitioners in primary care, rather than standard diagnostic criteria. We accept that there is a possibility of misclassification of IPF [19]. Unfortunately, it was not possible to validate the diagnostic coding because of the large quantity of data, but limited informal re-evaluation suggested that subjects did indeed have IPF. In a previous study evaluating IPF using data from the GPRD, Hubbard et al. [24] found the validity of IPF diagnoses in the database to be high; 95% of identified cases were found to be true positives. Furthermore, IPF can be difficult to diagnose, with patients usually only identified in secondary, or even tertiary, centers by multidisciplinary teams experienced in the diagnosis of ILD. We therefore believe that it is unlikely that a general practitioner would record a diagnosis of IPF without having received notification from a respiratory specialist in secondary care. The similar pattern in survival seen over time using both narrow and broad case definitions in our study also supports the validity of the IPF–CS diagnosis in our cases. With regards to case ascertainment, we feel that it is unlikely that many cases in the community would have been missed. This is because patients with IPF suffer chronic and progressive exertional dyspnea and cough for which they usually seek medical attention [1]. However, under-ascertainment of cases in our study is possible owing to the reliance on the transfer of information between secondary and primary care, and so some cases diagnosed in secondary care may have been missed. Another limitation is the possibility that some incident cases were misclassified and were actually prevalent cases. This would not have affected the observed trends in increased incidence or survival over time, but may have overestimated survival because prevalent cases have greater average survival than incident cases [3].

It should also be noted that a considerable proportion of patients were lost to follow-up (22% and 32% of patients in the narrow and broad definitions, respectively, over the first 5 years after diagnosis). Follow-up time for the incidence analysis was slightly lower using the broad definition than the narrow definition, as patients would have been identified as prevalent IPF patients at study initiation (using the broad definition) and were therefore excluded from the analysis. In some cases, censoring of patients may be linked to disease outcome; for example, IPF patients are more likely to move to a nursing home and change to another general practice prior to death, which would lower the estimated mortality rate.

Conclusions

This study provides estimates of the epidemiological burden of IPF in the UK. Our finding that the survival of patients with IPF–CS is very poor and has changed little over recent years undoubtedly reflects the lack of effective treatments available to patients with this devastating disease during this time period. The antifibrotic therapies pirfenidone, in 2013, and nintedanib, in 2015, have been approved for reimbursement in the UK by NICE for the treatment of adults with mild-to-moderate IPF. Since then pirfenidone has been shown, in a clinical trial setting, to reduce disease progression and to improve survival [25,26,27]. Whether the use of antifibrotic therapies [28] translates into increased survival in real-world patients with IPF will need to be evaluated in coming years. Electronic medical records, such as those in CPRD GOLD, constitute valuable data sources for the evaluation of IPF. Unlike CPRD GOLD, disease registries in most countries are limited by the fact that registration of IPF is not mandatory and therefore inclusion of cases is open to bias.

The results of this study provide an important benchmark against which the effects of changes in the management and treatment of IPF can be measured, and thereby lays the foundation for further research.

References

King TE Jr, Pardo A, Selman M. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet. 2011;378(9807):1949–61.

Baumgartner KB, Samet JM, Coultas DB, et al. Occupational and environmental risk factors for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a multicenter case–control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152(4):307–15.

Hubbard R, Johnston I, Britton J. Survival in patients with cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis: a population-based cohort study. Chest. 1998;113(2):396–400.

Gribbin J, Hubbard RB, Le Jeune I, et al. Incidence and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and sarcoidosis in the UK. Thorax. 2006;61(11):980–5.

Navaratnam V, Fleming KM, West J, et al. The rising incidence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the U.K. Thorax. 2011;66(6):462–7.

Raghu G, Chen SY, Yeh WS, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US Medicare beneficiaries aged 65 years and older: incidence, prevalence, and survival, 2001-11. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(7):566–72.

Mapel DW, Hunt WC, Utton R, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: survival in population based and hospital based cohorts. Thorax. 1998;53(6):469–76.

Thickett DR, Kendall C, Spencer LG, et al. Improving care for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in the UK: a round table discussion. Thorax. 2014;69(12):1136–40.

National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Pirfenidone for treating idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. April 2013; NICE technology appraisal guidance 282.

National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Nintedanib for treating idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. 2016; NICE technology appraisal guidance 379.

National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. The diagnosis and management of suspected idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. 2013.

Raghu G, Chen S-Y, Hou Q, Yeh W-S, Collard HR. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in US adults 18–64 years old. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(1):179–86.

Johnston I, Britton J, Kinnear W, Logan R. Rising mortality from cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. BMJ. 1990;301(6759):1017–21.

Hubbard R, Johnston I, Coultas DB, Britton J. Mortality rates from cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis in seven countries. Thorax. 1996;51(7):711–6.

Navaratnam V, Fogarty AW, Glendening R, McKeever T, Hubbard RB. The increasing secondary care burden of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: hospital admission trends in England from 1998 to 2010. Chest. 2013;143(4):1078–84.

American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(2):277–304.

Clinical Practice Research Datalink. 2014. http://www.cprd.com. Accessed Feb 2018.

Stuart-Buttle CD, Read JD, Sanderson HF, Sutton YM. A language of health in action: Read Codes, classifications and groupings. Proc AMIA Annu Fall Symp. 1996:75–9.

Herrett E, Gallagher AM, Bhaskaran K, et al. Data resource profile: Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(3):827–36.

Herrett E, Thomas SL, Schoonen WM, Smeeth L, Hall AJ. Validation and validity of diagnoses in the General Practice Research Database: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69(1):4–14.

Hansell A, Hollowell J, Nichols T, McNiece R, Strachan D. Use of the General Practice Research Database (GPRD) for respiratory epidemiology: a comparison with the 4th Morbidity Survey in General Practice (MSGP4). Thorax. 1999;54(5):413–9.

Raghu G, Weycker D, Edelsberg J, Bradford WZ, Oster G. Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(7):810–6.

Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(6):788–824.

Hubbard R, Venn A, Lewis S, Britton J. Lung cancer and cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. A population-based cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(1):5–8.

King TE Jr, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2083–92.

Fisher M, Nathan SD, Hill C, et al. Predicting life expectancy for pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2017;23(3-b Suppl):S17–S24.

Nathan SD, Albera C, Bradford WZ, et al. Effect of pirfenidone on mortality: pooled analyses and meta-analyses of clinical trials in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(1):33–41.

Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, et al. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2071–82.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This work was sponsored by InterMune UK and Ireland (now part of F. Hoffman La Roche). Roche Products Ltd funded the article processing charges and the Open Access fee.

Medical Writing Assistance

We thank and acknowledge Susan Bromley of EpiMed Communications Ltd (Oxford, UK), for medical writing assistance funded by the study sponsor (InterMune UK). We also thank and acknowledge Danielle Sheard and Eleanor Thurtle of Costello Medical (Cambridge, UK) for medical writing assistance with re-drafting the manuscript, funded by Roche Products Ltd.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published. All authors were involved in study design, in the analysis and interpretation of data, and in writing and reviewing the final manuscript. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosures

Toby M Maher has received industry-academic research funding from GlaxoSmithKline R&D, UCB, and Novartis and has received consultancy or speakers’ fees from Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Biogen Idec, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dosa, Galapagos, GlaxoSmithKline R&D, ProMetic, Roche (and previously InterMune), Sanofi-Aventis, and UCB. Toby M Maher is supported by an NIHR Clinician Scientist Fellowship (NIHR Ref: CS-2013-13-017) and a British Lung Foundation Chair in Respiratory Research (C17-3). Imran Kausar was an employee of InterMune UK at the time of the initial analysis; he is now self-employed. Helen Strongman has nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article reports a population-based cohort study and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

Data for this study can be accessed via application to CPRD. Investigators wishing to replicate the study would need to apply to CPRD using standard processes.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.5982208.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Strongman, H., Kausar, I. & Maher, T.M. Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival of Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis in the UK. Adv Ther 35, 724–736 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0693-1

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-018-0693-1