Abstract

Introduction

The estimation of utility values for the economic evaluation of therapies for wet age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a particular challenge. Previous economic models in wet AMD have been criticized for failing to capture the bilateral nature of wet AMD by modelling visual acuity (VA) and utility values associated with the better-seeing eye only.

Methods

Here we present a de novo regression analysis using generalized estimating equations (GEE) applied to a previous dataset of time trade-off (TTO)-derived utility values from a sample of the UK population that wore contact lenses to simulate visual deterioration in wet AMD. This analysis allows utility values to be estimated as a function of VA in both the better-seeing eye (BSE) and worse-seeing eye (WSE).

Results

VAs in both the BSE and WSE were found to be statistically significant (p < 0.05) when regressed separately. When included without an interaction term, only the coefficient for VA in the BSE was significant (p = 0.04), but when an interaction term between VA in the BSE and WSE was included, only the constant term (mean TTO utility value) was significant, potentially a result of the collinearity between the VA of the two eyes. The lack of both formal model fit statistics from the GEE approach and theoretical knowledge to support the superiority of one model over another make it difficult to select the best model.

Conclusion

Limitations of this analysis arise from the potential influence of collinearity between the VA of both eyes, and the use of contact lenses to reflect VA states to obtain the original dataset. Whilst further research is required to elicit more accurate utility values for wet AMD, this novel regression analysis provides a possible source of utility values to allow future economic models to capture the quality of life impact of changes in VA in both eyes.

Funding

Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Limited.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Wet age-related macular degeneration (wet AMD) is a chronic ophthalmic condition associated with severe visual impairment in older adults [1]. Left untreated, wet AMD leads to a progressive loss of visual acuity (VA; the ability of the eye to resolve fine detail) which affects the capacity to which patients can continue with routine activities such as driving, reading, and recognizing faces, and can have a substantial impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [2, 3].

In the United Kingdom (UK), measurement of HRQoL is an important aspect of the clinical benefit of novel therapies, where cost-utility analysis is the preferred method of health technology assessment (HTA) recommended by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) to assess the relative value of novel interventions to the UK National Health Service (NHS) [4]. In cost-utility analysis, the health benefits of a new treatment are expressed in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), where each year of life lived in a particular health state is weighted with a utility value (from 0 to 1) based on a valuation of preference for that health state [5, 6].

NICE guidance states that the measurement of changes in HRQoL should be reported directly from patients (e.g., collected directly from a clinical trial) [4]. The utility values associated with these changes should, however, be derived from a valuation of public preferences from a representative sample of the UK general population using a generic preference-based method (i.e., one applicable to a wide range of diseases, patients, and interventions, to allow for decision-making across the whole of the NHS) [4]. NICE’s preferred generic preference-based method of utility value elicitation is the EuroQol Health Questionnaire 5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)—a patient-reported questionnaire with five domains covering mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression—the scores of which can be converted to a validated set of utility values that have been valued by members of the UK general public using the time trade-off (TTO) methodology [7].

A recent systematic literature review identified eight publications reporting UK-derived utility values for wet AMD [2]. Only two UK-based utility studies have been published in wet AMD that use the NICE-preferred EQ-5D, demonstrating the paucity of data for this measure [8, 9]. Furthermore, neither of these studies found that the utility values elicited via this method reflected the change in visual impairment of the patients in the studies [8, 9]. This lack of relationship may lie with the descriptive nature of generic tools such as the EQ-5D, and the fact that the domains covered do not explicitly capture the impact of vision loss on activities of daily living, particularly for a disease such as wet AMD which is neither painful nor life-threatening.

Alternatively, several studies have elicited utility values via direct valuation from patients with AMD, using the TTO, standard gamble (SG), and visual analogue scale (VAS) valuation techniques [8,9,10,11]. The utilization of patients to directly value the utility of a certain health state lends itself to the possibility of underestimation of utility values due to the concept known as adaptation, when patients with a chronic condition adapt to their situation and therefore rate their health state less severely than would a member of the general population unaffected by the condition [12]. An additional concern with the valuation of hypothetical health states by members of the general public, however, is the ability of participants to accurately imagine these particular health states. In the study by Czoski-Murray et al., members of the general UK population were given contact lenses with a central opacity to simulate different states of vision loss, and utility values were elicited using the TTO methodology. When comparing the TTO-derived utilities with those derived via the Health Utilities Index-3 (HUI-3), EQ-5D, Short Form-6 Dimensions (SF-6D), and TTO by Espallargues et al. [8], Czoski-Murray et al. found a stronger significant correlation between VA in the BSE and the TTO-elicited utility values derived through the use of different contact lenses, than those derived by Espallargues et al. for the HUI-3 and the EQ-5D, as well as those elicited directly via TTO from a population of wet AMD patients (i.e., without contact lenses) [8]. Whilst the opacity of the contact lenses has been criticized for simplifying the full effects of wet AMD on VA [13, 14], the study by Czoski-Murray et al. offers an interesting attempt to address the challenges associated with utility value elicitation in wet AMD and forms the basis of the de novo regression analysis presented in this publication.

The economic models submitted to NICE for the technology appraisals of ranibizumab and pegaptanib in wet AMD were “one-eye” Markov state-transition models that assumed only the better-seeing eye (BSE) was treated, with utility values associated with VA of the BSE only [15]. Use of this approach assumes that any improvement in VA in the worse-seeing eye (WSE) results in no utility gain. In clinical practice, however, it is typically the first presenting eye that is treated and approximately 70% of these eyes are in fact the WSE [16, 17]. Nevertheless, the vast majority of published wet AMD utility studies have been performed on the basis of the VA of the BSE, for which there is most evidence of a correlation between VA and utility. By not including any effects on utility from the VA of the WSE within the economic evaluation of new therapies in wet AMD, the clinical benefit of the intervention under appraisal may be being underestimated. Conversely, in a case where utility values based on the VA of the BSE are used as a proxy for treatment of the WSE, the clinical benefit of a new treatment may be being overestimated. In the NICE technology appraisal of aflibercept for wet AMD, the health economic model submitted by the manufacturer was again criticized for being a “one-eye” model that assumed the untreated eye had no visual impairment at the start of the model. It was therefore representative of a WSE model, but the utility values used had been derived using EQ-5D within the pivotal clinical trial and therefore included a wider set of patients that was appropriate for a WSE model [18].

Whilst the utility values from the paper by Czoski-Murray et al. were considered appropriate in the technology appraisal for ranibizumab in wet AMD, they are based on VA of the BSE only and do not account for VA of the WSE [19]. Wet AMD is a bilateral disease yet there is a paucity of evidence on the extent to which changes in VA of the WSE contribute to overall patient HRQoL. In an attempt to address this limitation and the uncertainties raised by NICE regarding the estimation of utility values as a function of VA in both eyes, we present here a de novo regression analysis based on the dataset from Czoski-Murray et al. that explores the estimation of utility as a function of VA in both the BSE and the WSE [19]. This analysis was briefly introduced in a recent paper by Claxton et al. [14], and is presented in full in this publication.

Methods

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Description of Dataset

In the study by Czoski-Murray et al., a total of 108 subjects from the general UK population were recruited to wear three sets of custom-made contact lenses with differing central opacities [19]. The three sets of lenses were used to reproduce three states of differing VA representing differing severities of wet AMD, measured according to the logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution (LogMAR), with LogMAR scores of 0.6 (Snellen equivalent 20/80) (reading limit), 1.0 (20/200) (legal blindness), and 1.4 (20/500) (the state to which patients with untreated AMD deteriorate), respectively. The TTO technique was then used to assess participant valuation of their own health state both before wearing the lenses and during each of the three health state simulations [19].

The sampled population was considered younger (mean 32 years, 7 years younger than average UK population), more likely to be employed (66%), and more likely to be educated to degree level (28%) than the general public (Table 1) [19]. These background characteristics were explained by the difficulties in recruitment; 66 of the 108 subjects had to be recruited by word of mouth from colleagues and study participants after only 42 of a random sample of 2000 people attended to complete prior interviews [19]. Of the 108 subjects, four did not continue testing with all three contact lenses because of complications in the fitting process [19].

The original analysis by Czoski-Murray et al. adjusted the TTO-derived utility values for (i) the effect of the lenses, by removing all baseline observations so that differences in utility values between health states were due to the change in VA rather than the effect of the lens itself; and (ii) the order of the lenses, by adjusting the utility values for each of the possible lens orders using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression (Table 2) [19].

Methodology

In the Czoski-Murray et al. analysis, the relationship between the TTO-derived utility values and VA, with and without adjusting for age, was explored in the BSE only using OLS. In this extended re-analysis of the Czoski-Murray et al. dataset, LogMAR VA in the WSE was also included, thereby allowing the results to be used within health economic models that incorporate the effect of VA in both eyes on utility.

Five regression models were used to estimate the effect on utility of VA: (1) in the BSE alone; (2) in the WSE alone; (3) in both eyes independently; (4) in both eyes with an interaction between VA in the BSE and WSE; and (5) in both eyes with an interaction term and an additional blindness threshold. Models 4 and 5 were included to account for an effect on utility from the VA in both eyes, thereby allowing for a non-linear relationship between the influence of the VA on each eye. In both the analysis by Czoski-Murray et al. and early testing for this re-analysis, age was found to be a non-significant predictor of utility and hence was excluded as a covariate from all five models. All statistical modelling, including model fitting, inference, predictions, and validation, was carried out in Stata V14.1.

The five models are described below; β 0 is the constant term and represents the mean TTO utility value. Changes in VA in the BSE and WSE are denoted by the variables VABSE and VAWSE, respectively, which may be incorporated using either LogMAR or Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) letters data. In this re-analysis, the models were fitted with LogMAR VA data from the Czoski-Murray et al. study.

Model 1: BSE Model

Assumes utility is affected by VA in the BSE only. β 1 represents the mean change in TTO utility associated with a 1-unit change in VA of the BSE.

Model 2: WSE Model

Assumes utility is affected by VA in the WSE only. β 2 represents the mean change in TTO utility associated with a 1-unit change in VA of the WSE.

Model 3: BSE and WSE Model

Assumes utility is affected by VA in the BSE and WSE, independently. β 1 represents the mean change in TTO utility associated with a 1-unit change in VA in the BSE, if there is no change in VA in the WSE, and the reverse for β 2.

Model 4: BSE, WSE, and BSE–WSE Interaction Model

Assumes utility is affected by VA in the BSE and WSE independently, in addition to a combination of VA in the BSE and WSE. β 1 and β 2 have the same clinical interpretation as in model 3. If VAs of both the BSE and WSE change by 1 unit in the same direction, this additional mean change in TTO utility is represented by β 3.

Model 5: BSE, WSE, and BSE–WSE Interaction Model Plus “Blind” Variable

β 1 , β 2, and β 3 have the same clinical interpretation as in model 4. β 4BLIND is an indicator variable that takes a value of 1 if VA falls below 35 ETDRS letters (equivalent to LogMAR > 1.0) in both eyes (or zero otherwise), in relation to the psychological impact of a patient becoming legally blind.

As subjects contributed a maximum of three TTO values to the dataset from each of the three differing contact lens pairs, the data were therefore not fully independent and an OLS regression approach, which assumes data independence, would likely underestimate the standard errors of the coefficients, leading to the invalidation of further statistical tests. As such, generalized estimating equations (GEEs) were used to account for relationships between observations from the same individual and produce robust standard errors that better reflected the dependence structure in the data. GEEs no longer assume that the residual errors in the regression model are normally distributed and uncorrelated, but instead assume that the residual errors are correlated and can be estimated by a correlation matrix. The five models were fitted using the following three correlation structures:

-

Exchangeable Assumes equal correlation between all observations by the same subject

-

Independent Assumes no correlation between observations by the same subject, equivalent to an OLS approach

-

Unstructured Makes no assumptions about the correlations between observations by the same subject

The results from fitting all three correlation structures to each of the five models were compared. Since likelihood ratio tests are not available for GEEs, comparison between models concentrated on the root mean squared error (RMSE).

Results

In early testing, the relationship between the TTO-derived utility values and VA in both the BSE and WSE without interaction was explored using OLS. This suggested that the residuals were negatively skewed (Fig. S1), which may have been caused by a “ceiling” effect from many patients reporting a utility value of 1 (perfect health), leading to poor predictive quality at the extremes. Additionally, VAs in the BSE and WSE were found to be highly correlated, suggesting possible collinearity between these variables (Fig. S2).

Although there was little difference in model fit between the three correlation structures, the exchangeable structure was deemed the most clinically plausible because of the assumption that there would be equal correlation between subject observations in addition to the usual variation between observations from different subjects. Results from the exchangeable correlation structure are presented in Table 3; results from the independent and unstructured correlation structures are presented in the supplementary material (Tables S1 and S2).

Both VA in the BSE and VA in the WSE were found to be highly significant when regressed separately with the mean TTO-derived utility values in model 1 and model 2, respectively (both p < 0.01) (Table 3). As might be expected, the effect of VA in the BSE on utility was slightly higher than that of VA in the WSE (associated with a smaller p value). When VA in the BSE and VA in the WSE were included independently of each other in model 3, both variables had smaller coefficients and larger standard errors compared with those estimated in models 1 and 2, respectively. In model 3, only VA in the BSE was found to be significant (p = 0.04), but when an interaction term between VA in the BSE and WSE was included in model 4, only the constant term (mean TTO utility value) was found to be significant. Furthermore, the coefficient for VA in the WSE in model 4 was larger than the coefficient for VA in the BSE, and had a smaller standard error. The same conclusions were found with the inclusion of the BLIND indicator variable in model 5 which was also found to be a non-significant predictor of utility. Interestingly, on the basis of RMSE, there was little difference between all five models.

These results may be indicative of the presence of collinearity between VA in the BSE and VA in the WSE, which may be causing imprecision in the estimation of their coefficients when they are both included in the model. This is most noticeable with the inclusion of the interaction term in model 4 and model 5, where VA in the WSE was shown to have a larger independent effect than VA in the BSE. This would be considered clinically implausible and also led to no terms, including VA in either the BSE or WSE, being statistically significant. Similar conclusions were found when using the independent and unstructured correlation matrices (presented in supplementary material). Similarly, the lack of statistical significance of the BLIND variable may be due to the full psychological impact of becoming blind not being adequately captured by the subjects enrolled in the study as they were members of general UK population.

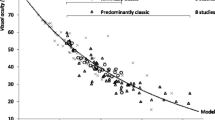

Figure 1 provides predicted utility estimates from each of the five regression models using the exchangeable correlation structure. Figures 1d and e indicate that as VA in the BSE decreases, the models with the BSE and WSE interaction term provide slightly higher utility estimates than the model without this interaction (Fig. 1b). There is also very little difference in prediction with the inclusion of the blindness threshold from model 4 to 5 (Fig. 1d, e), further indicating the non-significance of the BLIND variable.

Predicted utility estimates from models 1 to 5 (exchangeable structure). a Model 1: BSE model; b model 2: WSE model; c model 3: BSE and WSE model (independent); d model 4: BSE, WSE, and BSE–WSE interaction model; e model 5: BSE, WSE, and BSE WSE interaction model plus blind. BSE better-seeing eye, LogMAR logarithm of the minimal angle of resolution, WSE worse-seeing eye

Discussion

The estimation of utility values for the economic evaluation of therapies for wet AMD is associated with considerable challenges and uncertainty. In particular, the health economic models submitted for the NICE technology appraisals of ranibizumab, pegaptanib and aflibercept in wet AMD received criticism for failing to capture the bilateral nature of the disease [15, 18]. These health economic models only accounted for the treatment of one eye, assumed to be the BSE, with utility values linked to VA in the BSE only. Overall patient HRQoL derives from the VA in both eyes and, in clinical practice, the first eye to be treated is more often the WSE [20]. Modelling of the BSE only could lead to a recommendation for treatment in the BSE only, which may result in one eye known to be affected by AMD deteriorating without treatment, which could be associated with considerable patient anxiety and depression [15]. These typical “one-eye” cohort models do not enable changes in VA in both eyes to be modelled over time [15]; hence, modelling of the VA in both the BSE and the WSE, along with any resulting change in HRQoL from treatment of the WSE, is desirable.

Current approaches to the elicitation and application of utility values may, therefore, not be accurately capturing the potential QALY gains associated with treatment, which in turn may impact HTA decision-making. The regression analysis presented here advances the derivation of utility values for wet AMD in this regard. Five different regression models that explored utility as a function of VA in the BSE and WSE alone and together were evaluated using a GEE approach. Whilst utility was found to be statistically significantly related to VA in the BSE and WSE alone when evaluated independently (in models 1 and 2), the regression models that captured the impact of the change in VA in both eyes together (model 4 and model 5) may potentially be considered superior, as they allow for a non-linear relationship between VA and utility that is dependent on the VA of both eyes. However, the lack of formal model fit statistics available from the GEE approach and the shortage of theoretical knowledge to support the superiority of one model over another make it difficult to select the best model.

The relationship between VA and utility is a complex one, and whilst there are several aspects that can be considered, they are not easily explored. This analysis is limited by the degree of collinearity observed between the variables for the VA in the BSE and WSE; this is unsurprising given that two identical contact lenses were applied to each participant in each simulation state. This makes the effects of VA in the WSE and BSE difficult to disentangle and may have led to inflated standard errors and invalid conclusions regarding the individual coefficients for VA in the BSE and WSE in models 3–5. Although collinearity appears to be heavily influencing the coefficient estimates, the overall effect on model prediction is unclear. Earlier testing identified possible issues related to model prediction attributed to the “ceiling” effect which the GEE approach also fails to address. Furthermore, there is also the possible issue that when the VA of two eyes becomes quite similar, the BSE may not necessarily be the dominant eye. As the VA of the WSE improves, for example with treatment, this could potentially lead to a loss of utility, an aspect that is not factored into this analysis. Furthermore, this analysis evaluated only five selected models; hence, several other parametric models were not explored.

In addition, a limitation of this analysis arises from the nature of the original study conducted by Czoski-Murray et al. [19]. The population used in the dataset was much younger and more likely to be employed and educated to degree level than the general population. In addition, the use of contact lenses in the study by Czoski-Murray et al. [19] has been criticized for failing to capture the full effects of wet AMD on vision loss [13]. Indeed, a recent study by Butt et al. found that contact lenses are not a good simulation for the symptoms experienced, as people experience only a dimming of light and blurring of the image, rather than the true scotoma that would be expected with wet AMD [13]. Moreover, issues that emerged during the lens fitting process, with some patients unable to tolerate the use of the lenses, could have had an impact on the utility values reported [13]. As such, further work on a more representative set of the general population and using alternative methods such as virtual reality to aid the accurate simulation of vision loss associated with wet AMD would be of value. Additionally, the Czoski-Murray dataset does not meet the NICE reference case as it used TTO rather than EQ-5D to derive utilities. However, given the reported insensitivity of the EQ-5D and other generic measures to changes in VA, and that NICE has previously accepted the TTO values from Czoski-Murray et al., this analysis is still useful for future models in the UK setting. Furthermore, the Czoski-Murray et al. dataset was also used to inform the utility values for the health economic model constructed for the draft NICE clinical guidelines on the management of AMD, further highlighting the acknowledgement of this dataset by NICE [21].

The utility values derived using the different exchangeable regression models described here have been used in a recent economic evaluation of ranibizumab versus aflibercept for wet AMD [14]. This paper by Claxton et al. demonstrates the practical use of this regression analysis and its importance to future economic evaluations for this disease [14]. The results of this cost-effectiveness analysis demonstrated that the scenario that incorporated utility values based on the BSE eye only (model 1) provided a substantially higher estimate of total QALY gains compared with the scenario based on the WSE only (model 2), providing evidence to support the use of a “two-eye” regression model (i.e., models 3–5). In this cost-effectiveness analysis, regression models 3–5 included the VA of both eyes and provided QALY estimates in between those for model 1 and model 2 [14]. Utilization of a “two-eye” health economic model with a regression model based on the VA of both eyes to estimate utility values would enable the capture of visual improvement regardless of which eye is treated, and could therefore be considered most preferable. The modelling of two eyes, however, requires more sophisticated economic modelling techniques such as simulation modelling; hence, advances in both the derivation of utility values and the way in which economic models are built are needed to adequately capture changes in VA and HRQoL in the future economic evaluation of novel therapies in ophthalmology.

Conclusion

Further research is required to elicit more accurate utility values for wet AMD involving the VA of both eyes, in addition to advances in the technical economic modelling of ophthalmic conditions. Until such utility values are available, the regression analysis presented here represents a possible source of data that could be considered in the economic evaluation of future therapies for wet AMD in the UK, which will allow economic models to capture the quality of life impact of changes in VA in both eyes.

References

Lim LS, Mitchell P, Seddon JM, Holz FG, Wong TY. Age-related macular degeneration. Lancet. 2012;379(9827):1728–38.

Butt T, Tufail A, Rubin G. Health state utility values for age-related macular degeneration: review and advice. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15(1):23–32.

Mitchell J, Bradley C. Quality of life in age-related macular degeneration: a review of the literature. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:97.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013. 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg9/resources/guide-to-the-methods-of-technology-appraisal-2013-pdf-2007975843781. Accessed 13 Oct 2016.

Brazier J, Ratcliffe J, Salomon JA, Tsuchiya A. Measuring and valuing health benefits for economic evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Brown MM, Brown GC, Sharma S, Garrett S. Evidence-based medicine, utilities, and quality of life. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1999;10(3):221–6.

Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, Williams A. Valuing health states: a comparison of methods. J Health Econ. 1996;15(2):209–31.

Espallargues M, Czoski-Murray CJ, Bansback NJ, et al. The impact of age-related macular degeneration on health status utility values. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(11):4016–23.

Butt T, Dunbar HM, Morris S, Orr S, Rubin GS. Patient and public preferences for health states associated with AMD. Optom Vis Sci. 2013;90(8):855–60.

Bansback N, Czoski-Murray C, Carlton J, et al. Determinants of health related quality of life and health state utility in patients with age related macular degeneration: the association of contrast sensitivity and visual acuity. Qual Life Res. 2007;16(3):533–43.

Aspinall P, Hill A, Dhillon B, et al. Quality of life and relative importance: a comparison of time trade-off and conjoint analysis methods in patients with age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(6):766–72.

Albrecht GL, Devlieger PJ. The disability paradox: high quality of life against all odds. Soc Sci Med (1982). 1999;48(8):977–88.

Butt T, Crossland MD, West P, Orr SW, Rubin GS. Simulation contact lenses for AMD health state utility values in NICE appraisals: a different reality. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;99(4):540–4.

Claxton L, Hodgson R, Taylor M, Malcolm B, Pulikottil Jacob R. Simulation modelling in ophthalmology: application to cost effectiveness of ranibizumab and aflibercept for the treatment of wet age-related macular degeneration in the United Kingdom. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;35:237–48.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Ranibizumab and pegaptanib for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. Technology appraisal guidance [TA155]. 2008. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta155/resources/ranibizumab-and-pegaptanib-for-the-treatment-of-agerelated-macular-degeneration-82598316423109. Accessed 13 Oct 2016.

Bressler NM, Chang TS, Fine JT, Dolan CM, Ward J. Improved vision-related function after ranibizumab vs photodynamic therapy: a randomized clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(1):13–21.

Chang TS, Bressler NM, Fine JT, Dolan CM, Ward J, Klesert TR. Improved vision-related function after ranibizumab treatment of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: results of a randomized clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125(11):1460–9.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Aflibercept solution for injection for treating wet age-related macular degeneration. Technology appraisal guidance [TA294]. 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta294. Accessed 3 Nov 2016.

Czoski-Murray C, Carlton J, Brazier J, Young T, Papo NL, Kang HK. Valuing condition-specific health states using simulation contact lenses. Value Health. 2009;12(5):793–9.

Visser MS, Amarakoon S, Missotten T, Timman R, Busschbach JJ. SF-6D utility values for the better- and worse-seeing eye for health states based on the Snellen equivalent in patients with age-related macular degeneration. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0169816.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Age-related macular degeneration: diagnosis and management. Draft clinical guideline: methods, evidence and recommendations. 2017. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid-cgwave0658/documents/draft-guideline. Accessed 11 Aug 2017.

Acknowledgements

All costs associated with the development of this manuscript and any article processing charges were funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Limited.

The medical writing of this manuscript was conducted by Rose Wickstead, MPharm, from Costello Medical Consulting Ltd. No further support was provided to the authors with regards to medical writing, editorial, or other assistance.

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. All authors involved in the data analysis had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosures

R. Hodgson was an employee of York Health Economics Consortium at the time of conducting this work and was contracted by Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd to conduct some of the data analysis. L. Claxton was an employee of York Health Economics Consortium at the time of conducting this work and was contracted by Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd to conduct some of the data analysis. M. Taylor was an employee of York Health Economics Consortium at the time of conducting this work and was contracted by Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd to conduct some of the data analysis. T. Reason was an employee of Abacus International at the time of conducting this work and was contracted by Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd to conduct some of the data analysis. D. Trueman was an employee of Abacus International at the time of conducting this work and was contracted by Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd to conduct some of the data analysis. R. Wickstead is an employee of Costello Medical Consulting Ltd who was contracted by Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd to conduct the supporting literature review, appraise the data analysis and perform the medical writing of this manuscript. J. Kusel is an employee of Costello Medical Consulting Ltd who was contracted by Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd to conduct the supporting literature review, appraise the data analysis and perform the medical writing of this manuscript. A. Jasilek is an employee of Costello Medical Consulting Ltd who was contracted by Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd to conduct the supporting literature review, appraise the data analysis and perform the medical writing of this manuscript. R. Pulikottil-Jacob was an employee of Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd at the time of conducting this work.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/F15CF0600CF9FEBF.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Hodgson, R., Reason, T., Trueman, D. et al. Challenges Associated with Estimating Utility in Wet Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Novel Regression Analysis to Capture the Bilateral Nature of the Disease. Adv Ther 34, 2360–2370 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0620-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0620-x