Abstract

Introduction

Effective treatment for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) may lead to lower overall and RA-related healthcare utilization. We evaluated healthcare utilization before and after initiation of the tumor necrosis factor inhibitor etanercept in patients with moderate to severe RA.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study used data from the MarketScan® claims database. Data from adult patients with RA newly exposed to etanercept between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2013 were analyzed. Patients had at least one inpatient or outpatient claim for RA and at least one claim for etanercept (first claim was index date). Etanercept compliance was determined on the basis of proportion of days covered (PDC). Primary outcome was change in overall and RA-related healthcare utilization in the year before and year after etanercept initiation. McNemar’s test and paired t test, respectively, were used to determine statistical significance for dichotomous and continuous variables.

Results

Data from 6737 patients were analyzed; mean age was 49.8 years and 77.3% were female. Overall outpatient services, office visits, outpatient hospital services, laboratory visits, and emergency department visits were significantly lower in the post-index period compared to pre-index. RA-related pharmacotherapy use (oral corticosteroids, opioid analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs) was significantly lower in the post-index period compared to pre-index. Rates of RA-related total joint arthroplasty, joint reconstructions, and soft tissue procedures were similar in pre-index and post-index periods. High etanercept compliance (PDC ≥80%) was associated with significantly lower rates of RA-related outpatient services, office visits, diagnostic imaging studies, and joint reconstructions compared with noncompliance.

Conclusion

Overall healthcare utilization decreased after etanercept initiation. Patients who were most compliant with etanercept had significantly lower utilization than less compliant patients.

Funding

Amgen, Inc

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is characterized by persistent inflammation in joints, which leads to damage in the surrounding cartilage and bone. Recent estimates of RA indicate an incidence rate of 41 cases per 100,000 persons in the USA annually, affecting approximately 1.5 million US adults [1]. Treatments for RA include conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) or biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs). Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi), including adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol, are a class of bDMARDs that are currently approved to treat moderate to severe RA.

Patients with RA have high healthcare utilization (HCU) and costs compared to individuals without RA. An analysis from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey showed significantly higher total expenditures for RA patients compared with non-RA patients in 2008, which was primarily due to pharmacy costs [2]. A study from the Swedish National Patient Register using data from 2010 reported that mean annual costs were 2–3 times higher in RA patients than in the general population in 2010 [3]. The increasing use of bDMARDs since they became available in 1998, especially with new aggressive treat-to-target goals, has led to threefold to sixfold increases in direct costs in rheumatological practices across the EU [4]. However, the efficacy of bDMARDs in treating RA has led to lower hospitalization rates and lower rates of work disability, which can offset some of the medication costs [4].

Many RA HCU studies have focused on costs and they rarely focus on the actual drivers of HCU. Additionally, few studies have been published regarding the HCU specific to the TNFi medication etanercept. Given the demonstrated clinical effectiveness of etanercept [5], we hypothesized that HCU would decrease after etanercept initiation. The purpose of this study was to evaluate HCU before and after etanercept initiation in patients with RA, and to determine if any components of HCU decreased after etanercept initiation. We also compared HCU across levels of compliance with etanercept therapy.

Methods

Data Source

Data for these analyses were obtained from the Truven Health Analytics MarketScan® Database, an administrative claims database. The database includes health insurance claims from large employers and health plans across the USA, and contains de-identified fully adjudicated pharmacy claims (e.g., outpatient prescriptions) and medical claims (e.g., inpatient and outpatient services) submitted for payment by providers, healthcare facilities, and pharmacies. Claims include information on each physician visit, medical procedure, hospitalization, drugs dispensed, dates of service/prescription dispensing, number of days of medication supplied, and tests performed. Member enrollment and benefit information and limited patient and provider information are also available.

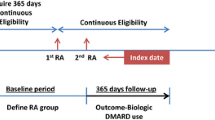

Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study, which used one-sample, pre–post analyses to compare differences in HCU before and after etanercept initiation. The full study period was 2009–2014, and patient identification was between 2010 and 2013. The index date was the date of the first etanercept claim during the patient identification period. Study outcomes were evaluated for the 12-month period before (baseline period) and the 12-month period after (follow-up period) etanercept initiation.

Patients

To be eligible, patients had to have initiated etanercept during the identification period, had at least one inpatient or outpatient claim with an RA diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] code 714.0) in the primary position during the 12 months prior to index date or on the index date, and 12 months of continuous enrollment in the health plan (with a pharmacy benefit) before and after the index date (total enrollment of 24 months). Patients were excluded for any of the following: claim for any bDMARD in the 12-month pre-index baseline period, age less than 18 years at start of baseline or over 64 years at index date, or a claim for psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, or juvenile idiopathic arthritis (other indications for etanercept) in the baseline period.

Study Outcomes

Etanercept utilization and HCU were assessed. The proportion of days covered (PDC) was the primary measure of etanercept utilization, and was calculated as the quotient of the number of days covered (using days supplied) during follow-up divided by 365 days. Assessment of HCU included office visits (for disease evaluation and management), inpatient admissions, emergency department visits, outpatient services (i.e., hospital outpatient clinic visits), RA-related procedures of total joint arthroplasty, joint reconstruction, and soft tissue repairs, RA-related pharmacotherapy, diagnostic tests, and select comorbidities. RA-related HCU was determined by a diagnosis of RA as the primary diagnosis on the claim for inpatient admissions and emergency department visits and by a diagnosis of RA in any position on outpatient services. Outpatient services were further stratified by office visits, outpatient hospital services, and laboratory visits. RA-related pharmacotherapies included TNFi medications and other bDMARDs (during follow-up only), and nonbiologic DMARDs (nbDMARDs), oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), oral corticosteroids, and oral opioid analgesics. Diagnostic tests included complete blood cell counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies, anti-mutated citrullinated vimentin antibodies, and a multi-biomarker disease activity test. HCU was identified using health insurance claims data by ICD-9-CM codes for diagnoses, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for procedures, National Drug Code (NDC) for medication dispensings, and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes for infused medications. Outcomes were evaluated in the 12-month baseline and post-index periods.

Statistical Considerations

Data transformations and statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics were generated for hospitalization (overall and RA-related), outpatient visits (overall and RA-related), and RA-related surgical procedures in the baseline and follow-up periods. For continuous outcome variables, the mean difference between baseline and follow-up values was estimated. For dichotomous outcome variables, the difference in proportions was estimated. The difference was calculated as the value during follow-up minus the value during baseline.

Statistical testing was performed using McNemar’s test for dichotomous variables, paired t test for continuous variables, and Wilcoxon signed rank test for nonparametric continuous variables. Post-index HCU was also evaluated for three categories of PDC: 0–39%, 40–79%, and 80–100% in secondary analyses. For these analyses, F test and Chi square test were used for continuous variables and categorical variables, respectively, and rank sum test was used for nonparametric continuous variables. The relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) of any emergency department visit (overall or RA-related) or any inpatient admission (overall or RA-related) was calculated as the post-index rate divided by the baseline rate, and 95% CIs were based on a naïve approach that assumed comparison groups were independent.

An analysis of HCU stratified by baseline use (yes/no) of nbDMARDs was conducted. A sensitivity analysis using a 90-day “skip period,” in which the 12-month follow-up period was started 90 days after index date, was conducted as a reduction in utilization with etanercept would have been underestimated if utilization temporarily increased shortly after treatment initiation.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

Patients

A total of 6737 patients were eligible to be included in the analysis (Fig. 1). The mean age was 49.8 years and 77.3% were female (Table 1).

HCU

RA-Related Pharmacotherapy

Use of nbDMARDs, oral corticosteroids, oral opioid analgesics, and oral NSAIDs was significantly lower after initiation of etanercept therapy (P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). The largest absolute decrease was seen for oral corticosteroid use (70.6% before and 56.7% after etanercept initiation). The mean [standard deviation (SD)] number of nbDMARDs used was 1.3 (0.8) during the pre-index period and 1.1 (0.7) in the follow-up period (P < 0.001).

RA-related pharmacotherapy before and after etanercept initiation. The percentage of patients with RA-related pharmacotherapy before (black bars) and after (gray bars) initiation of etanercept therapy. *P < 0.001 vs. pre-index use. nbDMARD nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug, NSAID nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, RA rheumatoid arthritis

Overall Health Services Utilization

The mean number of outpatient services, office visits, outpatient hospital services, laboratory visits, and emergency department visits was significantly lower after initiation of etanercept therapy (Fig. 3a). Patients treated with etanercept experienced on average one fewer office visit (17.1 before and 16.2 after etanercept initiation) and a reduction of almost 10% in any emergency department visits (RR 0.91; 95% CI 0.85–0.97).

Overall and RA-related health service utilization before and after etanercept initiation. a Overall and b RA-related health service utilization before (black bars) and after (gray bars) initiation of etanercept therapy is shown. Values represent mean numbers and error bars represent SD. *P < 0.001 vs. pre-index use. † P < 0.01 vs. pre-index use. ED emergency department, SD standard deviation

Patients who were most compliant with etanercept therapy (PDC ≥80%) had significantly lower overall health service utilization compared to patients with lower compliance (P < 0.001) (Table 2). Patients who were most compliant had on average three fewer office visits in the 12-month post-index period than those who were least compliant (14.7 vs. 17.7 visits). Patients with highest compliance also had significantly fewer emergency department visits compared to those with medium and low compliance (14.1% vs. 21.4% and 25.9%) and fewer inpatient hospital stays (6.4% vs. 11.9% and 13.5%).

RA-Related Health Services Utilization

Patients had significantly higher numbers of RA-related outpatient services and office visits but significantly lower numbers of emergency department visits, RA-related inpatient admissions, diagnostic laboratory tests, and diagnostic imaging studies after initiation of etanercept therapy (Fig. 3b). The post-index RR (95% CI) compared to pre-index for an RA-related emergency department visit was 0.61 (0.41–0.91), and for an RA-related inpatient admission was 0.56 (0.34–0.95).

Patients who were most compliant with etanercept therapy had significantly lower numbers of RA-related outpatient services (mean 6.4 for patients with PDC 80–100% vs. 6.8 for patients with PDC 40–79% and 7.4 for patients with PDC ≤39%; P < 0.001), office visits (mean 5.1 vs. 5.5 and 5.5; P = 0.002), diagnostic imaging studies (mean 1.6 vs. 2.1 and 2.4; P < 0.001), and joint reconstructions (mean 3.1% vs. 4.7% and 4.0%; P < 0.05) than patients in the lower compliance groups (Table 2).

Sensitivity Analyses

Medication use, comorbidities, and health service utilization at baseline and during the post-index period were similar with and without the 90-day skip period. Compared with patients who were receiving nbDMARDs at baseline, patients without baseline use of nbDMARDs had lower rates of oral corticosteroid, oral opioid analgesic, and oral NSAID use during the baseline period, and had fewer RA-related outpatient services [mean (SD) of 6.2 (4.3) and 3.7 (7.4) for patients with and without baseline nbDMARDs, respectively] and fewer RA-related office visits [mean (SD) of 5.0 (3.7) and 3.0 (7.0)].

Discussion

Prior studies have shown that the costs of treating RA and its comorbidities can be high [6, 7]. Conversely, there is also evidence that treatment with TNFi medications may lower HCU and costs [4, 8,9,10,11]. In the current study, initiation of etanercept led to significantly lower HCU among a cohort of RA patients for nearly all measures of interest. The mean number of outpatient services, office visits, outpatient hospital services, laboratory visits, and emergency department visits was significantly lower after initiation of etanercept therapy. Furthermore, patients with the highest level of compliance had the lowest amount of HCU. Although the reasons for changes in HCU were not collected in the study, patients with lower symptom burden and less active disease would have fewer reasons to make unscheduled visits to the rheumatologist, and patients using fewer RA medications would require fewer RA-related office visits. Only RA-related outpatient services and office visits were higher after etanercept initiation, which may reflect close monitoring of these patients immediately after initiating a new therapy.

While little literature exists on the impact of TNFi use on drivers of HCU, the findings of the current study are supported by other studies. Several studies have reported decreases in hospitalization rates among patients using TNFi medications [4, 8,9,10]. The rate of hospitalization has been shown to be higher in patients with RA compared with patients without RA, but only 2.5% of hospitalizations are due to RA and most are caused by comorbidities, notably cardiovascular and respiratory conditions [11]. In our study, hospitalization for any cause was equally likely before and after initiation of etanercept, but the post-index risk of RA-related hospitalization was 56% of baseline. As with other study outcomes, patients who were most compliant had fewer hospitalizations: 6.4% of patients with the highest compliance were admitted to the hospital for any reason compared to 13.5% of patients with the lowest compliance. While the reasons for noncompliance cannot be determined from our analysis, it is possible that complications from either the disease (e.g., joint replacement or poor access to medical services) or treatment (e.g., inadequate response or infection) could lead to noncompliance. No differences in baseline demographic or clinical characteristics were observed among the post-initiation PDC categories.

The rate of emergency department visits has been shown to decrease in patients using TNFi medications [10]. Emergency department visits have been shown to be more common in patients with RA than in patients without RA, but only 11.7% of visits are RA-related and most are due to comorbidities [11]. In our study, emergency department visits, which are twice as common as hospitalizations, also decreased in the post-index period both for any reason (91% of baseline risk) and for RA-related emergency department visits (61% of baseline risk). Among patients in the highest compliance category (PDC ≥80%), 14.1% had an emergency department visit for any reason vs. 25.9% for patients in the lowest category (PDC ≤39%).

Another major difference in HCU after etanercept initiation was the number of physician visits, which has also been observed in another study [12]. Overall, patients in the post-index period had one less office visit. More remarkable was the finding that the most compliant patients had on average three fewer office visits than those who were least compliant with their medication. More office visits for less compliant patients mean they had to spend more time traveling to and from the clinic (likely requiring assistance from a family member), and spending time checking in and waiting to see the physician, representing a large expenditure of personal time and/or time away from work. In a recent study conducted in Denmark, patients spent an average of 63 min of travel time for each visit, representing a total of 4.6 h every 3 months just traveling to appointments [13].

Similarly, the use of nbDMARDs, oral corticosteroids, oral opioid analgesics, and oral NSAIDs was significantly lower after initiation of etanercept therapy. This result is consistent with a retrospective analysis that showed reduced use of oral, intra-articular, intramuscular, and intravenous steroids in RA patients receiving TNFi medications [9]. This observation is notable, as decreased exposure also reduces the risk of adverse events associated with these medications, including liver and gastrointestinal toxicities with nbDMARDs (e.g., methotrexate, sulfasalazine, gold, penicillamine) [14, 15]; infection and myocardial infarction with oral corticosteroids [16, 17]; serious infections and nonvertebral fractures with opioid analgesics [18, 19]; and gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, and renal complications with NSAIDs [20].

We also conducted sensitivity analyses to examine the time to changes in utilization with etanercept initiation using a 90-day skip period, and whether use of baseline nbDMARDs affected HCU. Utilization results were virtually identical with and without the 90-day skip period. Patients without baseline use of nbDMARDs (which is not recommended) had generally lower post-index utilization and medication use than patients receiving nbDMARDs at baseline and also had smaller (and generally statistically non-significant) decreases in utilization from baseline. If this group had been excluded from the primary analysis, the observed effects of lower HCU after etanercept initiation would have been larger.

This study was subject to limitations inherent to claims analyses. Claims data have a risk of misclassification and coding errors. No data on disease activity or severity were available, although TNFi medications, including etanercept, are only indicated for moderate to severe RA. Reasons for poor compliance are unknown. Results represent commercially insured adults under 65 years of age and do not include patients with Medicaid, Medicare, or no insurance. Results may not be nationally representative. Strengths of the study include the large sample size of patients newly initiating etanercept therapy, the complete capture of utilization data in the database, and the pre–post design of the study, which allowed patients to act as their own controls.

Conclusions

Overall HCU decreased after etanercept initiation. Patients who were most compliant with their medication experienced significantly lower utilization than noncompliant patients. The reduction in HCU is consistent with a reduction in disease activity as shown in clinical trials of etanercept [5].

References

Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE. Is the incidence of rheumatoid arthritis rising?: Results from Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1955–2007. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:1576–82.

Kawatkar AA, Jacobsen SJ, Levy GD, Medhekar SS, Venkatasubramaniam KV, Herrinton LJ. Direct medical expenditure associated with rheumatoid arthritis in a nationally representative sample from the medical expenditure panel survey. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:1649–56.

Eriksson JK, Johansson K, Askling J, Neovius M. Costs for hospital care, drugs and lost work days in incident and prevalent rheumatoid arthritis: how large, and how are they distributed? Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:648–54.

Huscher D, Mittendorf T, von Hinüber U, et al. Evolution of cost structures in rheumatoid arthritis over the past decade. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:738–45.

Moreland LW, Schiff MH, Baumgartner SW, et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:478–86.

Shafrin J, Ganguli A, Gonzalez YS, Shim JJ, Seabury SA. Geographic variation in the quality and cost of care for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22:1472–81.

Franke LC, Ament AJ, van de Laar MA, Boonen A, Severens JL. Cost-of-illness of rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27:S118–23.

Zisman D, Haddad A, Hashoul S, et al. Hospitalizations of patients treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α agents – a retrospective cohort analysis. J Rheumatol. 2013;40:16–22.

Sandhu RS, Treharne GJ, Douglas KM, et al. The impact of anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy for rheumatoid arthritis on the use of other drugs and hospital resources in a pragmatic setting. Musculoskeletal Care. 2006;4:204–22.

Nair K, Ghushchyan V, Naim A. Effectiveness and costs of TNF-alpha blocker use for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2013;6:126–36.

Han GM, Han XF. Comorbid conditions are associated with healthcare utilization, medical charges and mortality of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35:1483–92.

Joyce GF, Goldman DP, Karaca-Mandic P, Lawless GD. Impact of specialty drugs on the use of other medical services. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:821–8.

Sørensen J, Linde L, Hetland ML. Contact frequency, travel time, and travel costs for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Rheumatol. 2014;2014:285951.

Katchamart W, Trudeau J, Phumethum V, Bombardier C. Efficacy and toxicity of methotrexate (MTX) monotherapy versus MTX combination therapy with non-biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1105–12.

Yazici Y. Long-term safety of methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28:S65–7.

Haraoui B, Jovaisas A, Bensen WG, et al. Use of corticosteroids in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab: treatment implications based on a real-world Canadian population. RMD Open. 2015;1:e000078.

Aviña-Zubieta JA, Abrahamowicz M, De Vera MA, et al. Immediate and past cumulative effects of oral glucocorticoids on the risk of acute myocardial infarction in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2013;52:68–75.

Wiese AD, Griffin MR, Stein CM, Mitchel EF Jr, Grijalva CG. Opioid analgesics and the risk of serious infections among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a self-controlled case series study. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:323–31.

Acurcio FA, Moura CS, Bernatsky S, Bessette L, Rahme E. Opioid use and risk of nonvertebral fractures in adults with rheumatoid arthritis: a nested case-control study using administrative databases. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:83–91.

Fine M. Quantifying the impact of NSAID-associated adverse events. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19:s267–72.

Acknowledgements

Sponsorship for this study and article processing charges were funded by Immunex, a wholly owned subsidiary of Amgen Inc. and by Wyeth, which was acquired by Pfizer in October 2009. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval of the version to be published. Editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Dikran Toroser (Amgen Inc.) and Julia R. Gage (on behalf of Amgen Inc.). Support for this assistance was funded by Amgen Inc.

Disclosures

Neil A. Accortt is an employee and shareholder of Amgen Inc. Jennifer Schenfeld is an employee of DOCS Global Inc. and received salary support from Amgen Inc. for this study. Eunice Chang is an employee of Partnership for Health Analytic Research, LLC, which received funding from Amgen Inc. for this study. Michael S. Broder is an employee of Partnership for Health Analytic Research, LLC, which received funding from Amgen Inc. for this study. Elya Papoyan is a former employee of Partnership for Health Analytic Research, LLC, which received funding from Amgen Inc. for this study.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available as they were obtained from MarketScan under a proprietary data use agreement.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/B4E8F0600DEF16E0.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Accortt, N.A., Schenfeld, J., Chang, E. et al. Changes in Healthcare Utilization After Etanercept Initiation in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Retrospective Claims Analysis. Adv Ther 34, 2093–2103 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0596-6

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0596-6