Abstract

Introduction

There is a growing interest in nutraceuticals improving cardiovascular risk factor levels and related organ damage.

Methods

This double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial aims to compare the effect of a combined nutraceutical containing red yeast rice (10 mg), phytosterols (800 mg), and l-tyrosol (5 mg) on lipid profile, blood pressure, endothelial function, and arterial stiffness in a group of 60 patients with polygenic hypercholesterolemia resistant to Mediterranean diet.

Results

After 8 weeks of treatment, when compared to the placebo group, the active treated patients experienced a more favorable percentage change in total cholesterol (−16.3% vs 9.9%, P < 0.001 always), LDL-C (−23.4% vs −13.2%, P < 0.001 always), and hepatic steatosis index (−2.8%, P < 0.01 vs −1.8%, P < 0.05). Moreover, ALT (−27.7%, P < 0.001), AST (−13.8%, P = 0.004), and serum uric acid (−12.3%, P = 0.005) were reduced by the tested nutraceutical compound both compared to randomization and to placebo, which did not affect these parameters (P < 0.01 for all). Regarding the hemodynamic parameters, there was a decrease of systolic blood pressure (−5.6%) with the active treatment not observed with placebo (P < 0.05 vs baseline and placebo) and endothelial reactivity improved, too (−13.2%, P < 0.001 vs baseline). Consequently, the estimated 10-year cardiovascular risk score improved by 1.19% (SE 0.4%) (P = 0.01) in the nutraceutical-treated patients.

Conclusion

The tested nutraceutical association is able to improve the positive effects of a Mediterranean diet on a large number of CV risk factors and consequently of the estimated CV risk.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT02492464.

Funding

IBSA Farmaceutici.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hypercholesterolemia is one of the major cardiovascular (CV) risk factors [1]. The initial therapeutic approach to hypercholesterolemia includes dietary modifications, but these are not always conclusive. For this reason, it may be useful to increase the dietary intake of compounds with potential cholesterol-lowering activity, normally present in small amounts in food [2]. There are a relatively large number of dietary supplements and nutraceuticals able to significantly reduce cholesterolemia in humans [3].

Phytosterols (plant sterols and stanols) are natural constituents of the cell membrane of plants [4]. Several clinical trials have consistently shown that intake of 2–3 g/day of plant sterols is associated with significant lowering (between 4% and 15%) of LDL-cholesterol [5,6,7]. Total cholesterol is also reduced to a similar extent, while it is uncertain whether the use of phytosterols has any beneficial effect on triglyceride levels [8, 9]. On the basis of the available data, the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA) accepted a health claim for the LDL-cholesterol-lowering effect of phytosterols [10].

Red yeast rice is a dietary supplement made by fermenting the yeast Monascus purpureus over rice. Monascus yeast produces a family of substances called monacolins, which act as reversible inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, the key enzyme in cholesterol biosynthesis. In addition to inhibitors of HMG-CoA reductase, red yeast rice has been found to contain sterols (β-sitosterol, campesterol, stigmasterol, and sapogenin), isoflavones, isoflavone glycosides, and monounsaturated fatty acids [11], all capable of lowering LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) [12]. Recently, red yeast rice has been used to lower LDL-C levels in patients who had to discontinue the use of statin medication due to muscle pains, confirming its good tolerability, both in terms of changes in biochemical parameters and muscle pain severity [13]. Red yeast rice is in fact similar to pravastatin in terms of LDL-C reduction (27% vs. 30%, P > 0.05), being associated with a lower rate of withdrawl from treatment [14]. Overall, on the basis of the available data, EFSA also accepted a health claim on the LDL-C-reducing effect of red yeast rice [15].

Moreover, nutraceuticals could improve dyslipidemia not only from a quantitative point of view but also from a qualitative one. For instance, l-tyrosol, a polyphenol highly concentrated in olive oil, is able to protect LDL particles from oxidative damage [16], making them less atherogenic.

In this context, the aim of this two-arm, double-blind randomized clinical trial is to comparatively test the effect on lipid pattern and endothelial reactivity of 8 weeks of treatment with phytosterols, red yeast rice, and l-tyrosine on moderately hypercholesterolemic subjects, as well as their tolerability.

Methods

Study Design

This single-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial involved 50 volunteers aged 35–69 years suffering from polygenic hypercholesterolemia resistant to Mediterranean diet (115 ≥ LDL-C ≤ 160 mg/dL as confirmed in at least two sequential checks). Patients with obesity (body mass index (BMI) >30 kg/m2], type 2 diabetes, a personal history of atherosclerosis-related cardiovascular disease (coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, or ultrasound-diagnosed carotid atherosclerosis), myopathy, renal failure, chronic liver disease, or current thyroid or gastrointestinal pathologies were excluded from the study, as well as subjects with any serious or invalidating other disease limiting full adhesion to the protocol.

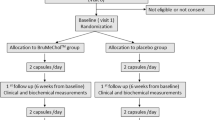

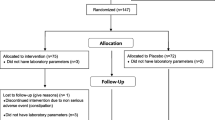

The CONSORT flow diagram is reported in Fig. 1.

The study included a 1-month-long run-in period of diet standardization, followed by a 2-month-long period of active treatment or placebo. At enrollment, patients were given standard behavioral and qualitative dietary suggestions to correct their unhealthy habits. In particular, subjects were strongly recommended to follow the general indications of a Mediterranean diet, avoiding an excessive intake of dairy and red meat-derived products, in order to maintain an overall balanced diet for the entire duration of the study. Patients were also strongly encouraged to increase their physical activity by walking briskly three to five times a week for at least 20 min every time.

The study fully complied with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and its protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Bologna (Clinicaltrial.gov ID NCT02492464). All participants signed a written informed consent to participate. The trial was carried out in line with the CONSORT statement.

Treatment

After 4 weeks of diet standardization, the enrolled subjects were allocated to treatment with two indistinguishable pills of placebo or of an active product (Colesia™, kindly provided by IBSA Farmaceutici, Milan, Italy), containing red yeast rice (5 mg monacolins/pill), 400 mg phytosterols/pill, and 2.5 mg l-tyrosol/pill. Patients were asked to take the pills regularly after dinner, at the same time every day.

The randomization was performed 1:1 ratio and the blocks were stratified by sex and age. An alphabetical code was assigned to each lot code (corresponding to treatment or placebo) impressed on the dose box. The study staff and the investigators, as well as all of the volunteers, were blinded to the group assignment. Codes were kept in a sealed envelope, which was not opened until the end of the trial. Dose boxes were mixed and a blinded dose box was assigned to each enrolled patient.

Treatment compliance was assessed by counting the number of pills returned at the time of specified clinic visits. At baseline, we weighed participants and gave them a bottle containing a supply of the study treatment for at least 33 days. Throughout the study, we instructed patients to take their first dose of new treatment product on the day after they were given it. All unused pills were retrieved for inventory. All treatment products were provided free of charge.

Patients’ personal history, a physical examination, and laboratory analyses were evaluated at the baseline, middle, and at end of the trial.

The hemodynamic variables recorded (endothelial function, arterial stiffness, and related parameters) were investigated before and after the intervention period. All instrumental measurements were carried out following standardized protocols by specially trained staff.

Assessments

Patients’ personal history was evaluated, paying attention to cardiovascular disease and other diseases, dietary and smoking habits (both evaluated with a validated semiquantitative questionnaire), physical activity, and pharmacological treatment.

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms (kg) divided by height in meters squared (m2). Height and weight were measured by standard procedures to the nearest 0.1 cm and 0.1 kg respectively, with subjects standing erect with eyes directed straight ahead, wearing light clothes, and with bare feet. Waist circumference (WC) was measured at the end of a normal expiration, in a horizontal plane at the midpoint between the inferior margin of the last rib and the superior iliac crest.

The biochemical analyses were carried out on venous blood, withdrawn in the morning from the basilic vein. Subjects had fasted for at least 12 h at the time of sampling. All the hematochemical measurements were centrally performed in our department’s laboratory. Plasma used was obtained by addition of Na2EDTA (1 mg/mL) and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 min at 48 °C. All the laboratory analyses were performed by trained personnel immediately after centrifugation, in accordance with standardized methods largely described elsewhere [17]. The hematochemistry variables investigated were total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides (TG), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), fasting glucose (FPG), serum uric acid (SUA), creatinine (Cr), alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), and creatinine phosphokinase (CPK). Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was estimated with the CKD-epi equation [18]. Lipid accumulation product (LAP) was calculated as (WC − 65) × TG (expressed in mmol/L) for men and (WC − 58) × TG (expressed in mmol/L) for women, and hepatic steatosis index (HSI) resulted from 8 × ALT/AST ratio + BMI (+2 for women) [19, 20].

Systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) values were detected in each subject supine and at rest, with a cuff applied at the right upper arm, by the use of the Vicorder® apparatus (Skidmore Medical Ltd, Bristol, UK), which is a validated oscillometric device guarantying an excellent intra- and interoperator reliability [21]. The endothelial function was evaluated, according to published guidelines [22], through the flow-mediated dilatation (FMD) of the right brachial artery, using the Endocheck® (BC Biomedical Laboratories Ltd, Vancouver, BC, Canada), which is embedded in the Vicorder® system. The test was carried out before the morning drug intake, with patients in supine position and having abstained from cigarette smoking and caffeinated beverages for at least 12 h. The brachial pulse volume (PV) waveforms were recorded for 10 s at baseline and then during reactive hyperemia, which was provoked through PV displacement, obtained by inflating up to 200 mmHg for 5 min a cuff positioned distally around the forearm. When the cuff was released, the PV waveforms were recorded again for 3 min. The percentage PV displacement was calculated as the percentage change from baseline to peak dilatation [23]. All of the hemodynamic measurements were performed by a trained physician who was blinded to the treatment groups.

The 10-year cardiovascular risk was assessed using the CUORE project risk score, built within the Italian CUORE project, carried out under the supervision of the National Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Ministry of Health, Rome [24, 25]. The CUORE project risk score allows one to estimate the probability of experiencing a first CV event (myocardial infarction or ischemic stroke) over the next 10 years, by knowing age, sex, SBP, TC, HDL-C, presence or absence of diabetes mellitus, smoking habit, and use of antihypertensive medication. It was validated in patients aged 35–69 years without previous major cardiovascular accidents. On the basis of the CUORE project risk score, enrolled patients were classified as low risk (CUORE project risk score <3.0%), intermediate risk (CUORE project risk score 3.0–19.9%), and high risk (CUORE project risk score ≥20.0%). Data were analyzed using the software cuore.exe, freely downloadable from the institutional website of the CUORE project [26].

Statistical Analyses

Sample size was calculated for both primary outcomes (LDL-C decrease and FMD improvement). Considering a type I error of 0.05 and a power of 0.80 and expecting a minimum LDL-C reduction of 1.0 mg/dL with an SD of 0.1, and considering a 20% dropout rate, we calculated the need to enroll 50 patients (25 per arm). This calculation was also valid to detect significant changes in endothelial reactivity. Data were analyzed using intention to treat by means of the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 21.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for Windows. The normal distribution of the tested parameters was evaluated by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The baseline characteristics of the population were described by the independent t test and the χ 2 test, followed by Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Every continuous parameter was compared by repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). The intervention effects were adjusted for all of the considered potential confounders by the analysis of covariance (ANCOVA). ANOVA was performed to assess the significance within and between groups. The statistical significance of the independent effects of treatments on the other variables was determined by the use of the ANCOVA. A one-sample t test was used to compare the values obtained before and after the treatment administration; two-sample t test were used for between-group comparisons. Turkey’s correction was carried out for multiple comparisons.

All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Every test was two-tailed. P values less than 0.05 were always regarded as statistically significant.

Results

All volunteers (30 men and 20 women) completed the trial according to the study design (Fig. 1). At randomization, 25 (50%) patients were assigned to Colesia™ and 25 (50%) to placebo. Overall, compliance was 97%. Considering the assumed products, the final sex-related distribution did not show any significant difference (χ 2 < 0.001, P > 0.05). The two study groups were well matched for all of the considered variables at baseline (P > 0.05 always) (Table 1). No patient experienced any kind of subjective or laboratory adverse events and active treatment was as well tolerated as the placebo.

From the randomization visit until the end of the study, the enrolled subjects declared to have maintained similar dietary habits, without significant change in total energy, TC, and total saturated fatty acid intake. However, we recorded a significant improvement in waist circumference in both treated groups, while BMI got better only in the placebo group. After 8 weeks of treatment, when compared to the placebo group, the active treated patients experienced a more favorable percentage change in TC (−16.3% vs −9.9%, P < 0.001 always), LDL-C (−23.4% vs −13.2%, P < 0.001 always), and HSI (−2.8%, P < 0.01 vs −1.8% P < 0.05) (Table 2). Moreover, ALT (−27.7%, P < 0.001), AST (−13.8%, P = 0.004), and SUA (−12.3%, P = 0.005) were reduced by Colesia™ both compared to randomization and to placebo that did not affect these parameters (P < 0.01 for all).

Regarding the hemodynamic parameters, there was a decrease of SBP with Colesia™ (−5.6%, P = 0.013) not observed with placebo (P < 0.05 vs baseline and placebo) and FMD improved, too (−13.2%, P < 0.001 vs baseline).

No significant change was observed concerning the other hematochemistry and hemodynamic parameters considered (Table 2).

Considering the effects of Colesia™ on blood pressure and lipid levels, the estimated 10-year CV risk score improved by 1.19% (SE 0.4%) (P = 0.01) in the nutraceutical-treated patients. As a consequence, 40% of the treated subjects were reassigned to a lower estimated risk category.

Discussion

In our study we observed that Colesia™ is effective in reducing lipid profile and serum uric acid and improving SPB and endothelial function in subjects with polygenic hypercholesterolemia resistant to Mediterranean diet. Our results are in line with a recent report by Feuerstein and Bjerke who evaluated the effects of a phytosterol/red yeast rice fixed combination on lipid parameters [27]. The positive effect of red yeast rice and phytosterols on LDL-C was also reported by our group in a previous published clinical study [28]. However, the combined effect of l-tyrosol with phytosterols and red yeast rice was never investigated up to now.

Even if the reduction in CV risk estimated with the conventional algorithm is relatively small with Colesia™, its effect on CV risk is presumably larger. In fact, Colesia™ use was associated with an increase in flow-mediated dilation, and a recent meta-analysis of clinical data shows that 1% improvement in FMD is associated with a 12% in CV risk [29]. Moreover, according to a large meta-analysis from the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration [30], the LDL-C reduction achieved in our study has been associated with a long-term reduction of CV risk of about 20% in statin-treated subjects. Therefore, Colesia™ is also associated with a small but significant decrease in SUA, and SUA is also an emerging risk factor for CVD [31].

Certainly, our study has some limitations. The first one is the relatively small sample size. However, the study power appears to be adequate for the primary endpoints, as previously declared. The second limitation is the relatively short duration of the trial; however, it is comparable with most exploratory trials carried out with metabolically active nutraceuticals. Third, we did not describe a specific diet based on bromatological data, but we gave only general dietary suggestions. On the one hand, this probably attenuated the positive effects of diet per se; on the other hand, it simulates more strictly what is routinely done in general practice. We did not measure the possible changes of signalling molecules such as bradykinin, adenosine, vascular endothelial growth factor, serotonin, or NO synthase, also related to endothelial function, but we limited our observation to the instrumental investigation of vascular parameters. Finally, the results we reported are valid for red yeast rice formulation standardized for the same monacolin concentration, and cannot be applied to other over-the-counter non-standardized ones given at a similar dosage.

The main strength and novelty of our study is to have tested the middle-term effect of monacolins and phytosterols plus l-tyrosol on endothelial function at the same time. However, larger studies are required to confirm this observation.

Conclusion

The tested nutraceutical association is able to improve the positive effects of a Mediterranean diet on a large number of CV risk factors and consequently of the estimated CV risk.

References

Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, et al. 2016 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: the task force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (EACPR). Atherosclerosis. 2016;253:281–344.

Pirro M, Vetrani C, Bianchi C, Mannarino MR, Bernini F, Rivellese AA. Joint position statement on “nutraceuticals for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia” of the Italian Society of Diabetology (SID) and of the Italian Society for the Study of Arteriosclerosis (SISA). Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2017;27(1):2–17.

Cicero AF, Ferroni A, Ertek S. Tolerability and safety of commonly used dietary supplements and nutraceuticals with lipid-lowering effects. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2012;11(5):753–66.

Law M. Plant sterol and stanol margarines and health. Br Med J. 2000;320:861–4.

Blair SN, Capuzzi DM, Gottlieb SO, Nguyen T, Morgan JM, Cater NB. Incremental reduction of serum total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol with the addition of plant stanol ester-containing spread to statin therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86:46–52.

Lichtenstein AH, Deckelbaum RJ. Stanol/sterol ester-containing foods and blood cholesterol levels. A statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism of the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2001;103:1177–9.

Mannarino E, Pirro M, Cortese C, et al. Effects of a phytosterol-enriched dairy product on lipids, sterols and 8-isoprostane in hypercholesterolemic patients: a multicenter Italian study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;19:84–90.

Plat J, Brufau G, Dallinga-Thie GM, Dasselaar M, Mensink RP. A plant stanol yogurt drink alone or combined with a low-dose statin lowers serum triacylglycerol and non-HDL cholesterol in metabolic syndrome patients. J Nutr. 2009;139:1143–9.

Wu T, Fu J, Yang Y, Zhang L, Han J. The effects of phytosterols/stanols on blood lipid profiles: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2009;18:179–86.

EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific opinion on the modification of the authorisation of a health claim related to plant sterol esters and lowering blood LDL-cholesterol; high blood LDL-cholesterol is a risk factor in the development of (coronary) heart disease pursuant to article 14 of regulation (EC) No 1924/2006, following a request in accordance with article 19 of regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA J. 2014;12(2):3577. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2014.3577.

Ma J, Li Y, Ye Q, et al. Constituents of red yeast rice, a traditional Chinese food and medicine. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48(11):5220–5.

Herber D, Yip I, Ashley JM, Elashoff DA, Elashoff RM, Go VLW. Cholesterol-lowering effects of a proprietary Chinese red-yeast rice dietary supplement. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:231–6.

Becker DJ, Gordon RY, Halbert SC, French B, Morris PB, Rader DJ. Red yeast rice for dyslipidemia in statin-intolerant patients: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:830–9.

Halbert SC, French B, Gordon RY, et al. Tolerability of red yeast rice (2,400 mg twice daily) versus pravastatin (20 mg twice daily) in patients with previous statin intolerance. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:198–204.

EFSA Panel on Dietetic Product, Nutrition and allergies (NDA)s. Scientific opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to monacolin K from red yeast rice and maintenance of normal blood LDL-cholesterol concentrations (ID 1648, 1700) pursuant to article 13(1) of regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA J. 2011;9(7):2304.

EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to polyphenols in olive and protection of LDL particles from oxidative damage (ID 1333, 1638, 1639, 1696, 2865), maintenance of normal blood HDL cholesterol concentrations (ID 1639), maintenance of normal blood pressure (ID 3781), “anti-inflammatory properties” (ID 1882), “contributes to the upper respiratory tract health” (ID 3468), “can help to maintain a normal function of gastrointestinal tract” (3779), and “contributes to body defences against external agents” (ID 3467) pursuant to article 13(1) of regulation (EC) No 1924/2006. EFSA J. 2011;9:4–2033.

Cicero AF, Rosticci M, Bove M, et al. Serum uric acid change and modification of blood pressure and fasting plasma glucose in an overall healthy population sample: data from the Brisighella heart study. Ann Med. 2017;49:275–82.

Earley A, Miskulin D, Lamb EJ, Levey AS, Uhlig K. Estimating equations for glomerular filtration rate in the era of creatinine standardization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:785–95.

Cicero AF, D’Addato S, Reggi A, Reggiani GM, Borghi C. Hepatic steatosis index and lipid accumulation product as middle-term predictors of incident metabolic syndrome in a large population sample: data from the Brisighella Heart Study. Intern Emerg Med. 2013;8(3):265–7.

Cicero AF, D’Addato S, Reggi A, Marchesini G, Borghi C, Brisighella Heart Study. Gender difference in hepatic steatosis index and lipid accumulation product ability to predict incident metabolic syndrome in the historical cohort of the Brisighella Heart Study. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2013;11:412–6.

McGreevy C, Barry M, Bennett K, Williams D. Repeatability of the measurement of aortic pulse wave velocity (aPWV) in the clinical assessment of arterial stiffness in community-dwelling older patients using the Vicorder(®) device. Scand J Clin Lab Investig. 2013;73:269–73.

Corretti MC, Anderson TJ, Benjamin EJ, et al. Guidelines for the ultrasound assessment of endothelial-dependent flow-mediated vasodilation of the brachial artery: a report of the International Brachial Artery Reactivity Task Force. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39(2):257–65.

Day LM, Maki-Petaja KM, Wilkinson IB, McEniery CM. Assessment of brachial artery reactivity using the Endocheck: repeatability, reproducibility and preliminary comparison with ultrasound. Artery Res. 2013;7:119–20.

Palmieri L, Panico S, Vanuzzo D, et al. Evaluation of the global cardiovascular absolute risk: the Progetto CUORE individual score. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2004;40:393–9.

Palmieri L, Rielli R, Demattè L, et al. CUORE project: implementation of the 10-year risk score. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2011;18:642–9.

http://www.cuore.iss.it/. Accessed 1 May 2017.

Feuerstein JS, Bjerke WS. Powdered red yeast rice and plant stanols and sterols to lower cholesterol. J Diet Suppl. 2012;9:110–5.

Cicero AF, Derosa G, Pisciotta L, Barbagallo C, SISA-PUFACOL Study Group. Testing the short-term efficacy of a lipid-lowering nutraceutical in the setting of clinical practice: a multicenter study. J Med Food. 2015;18:1270–3.

Matsuzawa Y, Kwon TG, Lennon RJ, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Prognostic value of flow-mediated vasodilation in brachial artery and fingertip artery for cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e002270.

Fulcher J, O’Connell R, Voysey M, et al. Efficacy and safety of LDL-lowering therapy among men and women: meta-analysis of individual data from 174,000 participants in 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;385:1397–405.

Borghi C, Cicero AFG. Serum uric acid and cardiometabolic disease: another brick in the wall? Hypertension. 2017;69:1011–3.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the University of Bologna Instutional funding. IBSA Farmaceutici (Milan, Italy) funded the article processing charges and open access fee. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. IBSA Farmaceutici (Milan, Italy) provided the tested product and the related placebo. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosures

Arrigo Cicero, Federica Fogacci, Marilisa Bove, Maddalena Veronesi, Manfredi Rizzo, Marina Giovannini, and Claudio Borghi have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Data Availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Thanks to Patient Participants

We are sincerely grateful to all the patients who agreed to participate in this trial.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/FAD8F0603046763F.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cicero, A.F.G., Fogacci, F., Bove, M. et al. Short-Term Effects of a Combined Nutraceutical on Lipid Level, Fatty Liver Biomarkers, Hemodynamic Parameters, and Estimated Cardiovascular Disease Risk: A Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial. Adv Ther 34, 1966–1975 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0580-1

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-017-0580-1