Abstract

Introduction

Ranibizumab and aflibercept are anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents licensed for the treatment of visual impairment due to macular edema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO). The aim of this study was to estimate, from a UK healthcare payer’s perspective, the cost-effectiveness of ranibizumab versus aflibercept in this indication.

Methods

A Markov model was used to simulate the outcomes and costs of treating BRVO. Patient baseline characteristics and efficacy data for ranibizumab were obtained from the BRAVO trial. The relative efficacy of aflibercept was derived from a published network meta-analysis. Injection frequencies were derived from ranibizumab and aflibercept studies included in the network meta-analysis. Health states were defined by increments of 10 letters in best corrected visual acuity (BCVA). Patients could gain or lose a maximum of two health states between cycles. The first cycle was 6 months, followed by monthly cycles. Different utility values were assigned to the better-seeing and worse-seeing eyes based on BCVA. A 2-year treatment time frame and a lifetime time horizon were used. Future costs and health outcomes were discounted at 3.5% per annum. Sensitivity analyses were used to test the robustness of the model.

Results

The lifetime cost per patient treated was £15,273 with ranibizumab and £17,347 with aflibercept. Ranibizumab was dominant over aflibercept, producing incremental health gains of 0.0120 quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and cost savings of £2074. Net monetary benefit for ranibizumab at a willingness-to-pay threshold of £20,000/QALY was £2314. Sensitivity analyses showed that the results were robust to variations in model parameters.

Conclusions

Ranibizumab provides greater health gains at a lower overall cost than aflibercept in the treatment of visual impairment due to macular edema secondary to BRVO. Ranibizumab is therefore cost-effective from a UK healthcare payer’s perspective.

Funding

Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) occurs when a thrombus obstructs a retinal vein [1] and is one of the most common causes of visual loss in older adults [2, 3]. In central RVO, the blockage occurs in the main retinal vein at the optic nerve; in branch RVO (BRVO), it occurs at an arteriovenous crossing where an artery and vein share a common vascular sheath. Retinal vein thrombosis raises retinal capillary pressure, which results in increased capillary permeability. Increased levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) are triggered, which augment vascular permeability and proliferation of new vessels [1]. Macular hemorrhage, edema, and ischemia can develop and affect the severity of vision loss; of these, macular edema is most frequently responsible, and develops in 5–15% of eyes with BRVO [4].

The prevalence of BRVO has been estimated to be 4.42 per 1000 persons, based on pooled data from population-based studies in the USA, Europe, Asia, and Australia [3]. In England and Wales, approximately 11,600 people with BRVO have visual impairment (VI) each year as a result of macular edema [1]. Vision loss can impede usual daily activities, resulting in dependency on others and significant reductions in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [5]. Increased healthcare utilization and expenditure, costly rehabilitation services, and the need for caregiver time can increase the socioeconomic burden of RVO [5, 6].

The treatments routinely used in the UK National Health Service (NHS) for BRVO are ranibizumab and grid laser photocoagulation. A recent UK economic evaluation concluded that ranibizumab was cost-effective relative to grid laser photocoagulation [7].

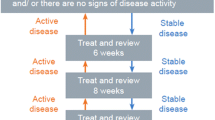

Ranibizumab is a monoclonal anti-VEGF-A antibody fragment licensed for the treatment of VI due to macular edema secondary to RVO [8, 9]. Under its current EU label, a dose of 0.5 mg is administered by intravitreal injection (IVI) once per month until maximum visual acuity is achieved and/or there are no signs of disease activity. In patients with RVO, initially, three or more consecutive monthly injections may be needed. Thereafter, monitoring and treatment intervals should be determined by the physician and should be based on disease activity as assessed by visual acuity and/or anatomical parameters [9]. The use of ranibizumab in BRVO has been evaluated in two pivotal trials: BRAVO (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT00486018) [10] and HORIZON (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01442064) [11]. In BRAVO, ranibizumab 0.5 mg provided a rapid and significant improvement in visual acuity compared with sham injections [10]; patients in the ranibizumab group gained a mean of 18.3 letters on the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study scale, compared with 7.3 letters in the sham group (P < 0.0001). In addition, 61% of patients receiving ranibizumab gained 15 letters or more, compared with 29% receiving sham injection (P < 0.0001). Visual improvement was maintained for the next 6 months (through to month 12), during which ranibizumab was given as required [12] and maintained for a total of 24 months, as demonstrated in the 12-month HORIZON open-label extension trial [11].

A second anti-VEGF agent, aflibercept (a fully human recombinant fusion protein), is licensed for the treatment of macular edema secondary to RVO [13]. The phase 3 VIBRANT trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01521559) showed that in patients with VI due to macular edema secondary to BRVO, aflibercept administered at a dose of 2.0 mg by IVI every 4 weeks provided greater visual improvement than grid laser photocoagulation at 24 weeks [14]: 53% of eyes treated with aflibercept gained 15 letters or more from baseline at week 24, compared with 27% of those receiving laser treatment (P = 0.0003). Eyes treated with aflibercept gained an average of 17.0 letters, compared with 6.9 letters when treated with laser (P < 0.0001).

Given the socioeconomic burden of VI caused by BRVO, it is important to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of therapies licensed for this condition. At the time of this study, we are unaware of UK economic evaluations in the peer-reviewed literature comparing ranibizumab with aflibercept in BRVO. The objective of this study was to compare the cost-effectiveness of ranibizumab with aflibercept from a UK healthcare payer’s perspective.

Methods

Model Structure

This study was based on a Microsoft Excel Markov model used in a submission to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [15]. The model, which simulated the health outcomes, utilities and costs experienced by patients treated with ranibizumab for macular edema secondary to RVO, was adapted by including aflibercept as a comparator. Internal calculations and settings in the model were revised to accommodate the new arm. The model was populated using data from the BRAVO trial [10] and a published network meta-analysis (NMA) [16]. It followed a cohort of patients, whose baseline characteristics were derived from the BRAVO trial: their mean age was 67.5 years and 51% of patients had a baseline best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 56–75 letters (Table 1) [10]. Based on the proportion of patients whose study eye was the better-seeing eye (BSE) or worse-seeing eye (WSE) at baseline in the BRAVO trial, it was assumed that 10% of treatments would be in the patient’s BSE, increasing to 21.5% at 12 months [7].

In the Markov model, patients cycled between eight health states defined by BCVA intervals ranging from <25 letters to 86–100 letters, and a ninth absorbing ‘death’ state (Fig. 1). The first cycle was 6 months, in line with the published comparative effectiveness data; monthly cycles were applied thereafter. Patients could move up or down a maximum of two health states within each cycle over a lifetime time horizon. A half-cycle correction was applied.

The timeframe for anti-VEGF treatments was assumed to be 2 years. The first-year transition probabilities (TPs) for the ranibizumab arm were calculated using the full analysis set comprising 12-month data from the BRAVO trial [10, 12]. The treatment effect was assumed to be maintained in the second year, in line with the results of the HORIZON trial [11]. It was assumed that patients did not receive any treatment from year 3 onwards, and the natural decline in BCVA was modeled based on data from a population-based observational study [17]. This enabled the calculation of a 0.031% monthly probability of losing 10–20 letters, as used in the NICE submission [7, 15].

There are no published head-to-head trials comparing the efficacy of ranibizumab and aflibercept. The TPs for the aflibercept arm were therefore calculated using the odds ratio (OR) versus ranibizumab from a published NMA [16]. The NMA was based on eight randomized controlled trials involving 1743 adult patients and included an assessment of the baseline patient characteristics as well as adjustments for different BCVA levels across the trials. The results showed that there were numerical differences in efficacy for ranibizumab versus aflibercept for the proportion of patients gaining 15 letters or more from baseline [OR 1.06; 95% credible interval (CrI) 0.16–8.94].

The OR from the NMA was assumed to apply to a gain of 10 letters or more in the first 6-month cycle. In addition, the percentages of patients losing 10 letters or more between two cycles were assumed to be the same in the ranibizumab and aflibercept arms. Following the first cycle, the same TPs were assumed for both arms, given the lack of comparative data. Effectiveness was assumed to be constant across all visual acuity levels. The TP calculations for aflibercept are presented in Table S1 in the supplementary material.

It was assumed that the rate of adverse events for ranibizumab and aflibercept was the same, consistent with the NICE assessment of aflibercept in neovascular age-related macular degeneration [18].

All-cause mortality was included in the model using annual rates based on life tables for England and Wales. In line with a previous model in BRVO, it was assumed that worsening in BCVA was associated with increased mortality. In the BSE, a risk ratio of 1 was applied to BCVA letter scores above 56, 1.23 for 36–55 letters, and 1.54 for below 36 letters. In the WSE, a risk ratio of 1.23 was applied only for BCVA levels below 35 letters [7].

Utility Values

Utility values for each health state were assigned based on BCVA and whether the treated eye was the BSE or WSE. Utility values for the BSE health states were obtained from a recent cost-effectiveness evaluation in diabetic macular edema (DME) [19]: the values, which were calculated using data from Czoski-Murray et al. [20], ranged from 0.850 for the best possible state to 0.353 for the worst possible state. For the WSE, due to the absence of appropriate data, it was assumed that patients could experience a maximum gain of 0.1 utility between the best and worst states (compared with 0.52 in the BSE). Table 2 shows the utility values in the BSE according to BCVA.

Resource Use

The number of ranibizumab injections in the first 6 months was based on a weighted mean of the number of injections reported in ranibizumab studies included in the NMA [BRAVO, BRIGHTER (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01599650) and COMRADE-B (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT01396057)] [16]. A similar approach was used in an economic model for DME submitted to NICE [21]. The injection frequency for months 7–12 was obtained from the BRAVO trial [12]. Aflibercept injection frequencies for the first year were obtained from the VIBRANT trial [14, 22]. For the second year, ranibizumab injection frequency was obtained from the HORIZON trial, after excluding patients who did not enter the extension study [7, 11]. The same injection frequency was assumed for aflibercept in year 2. The assumption around the number of monitoring visits was in line with the NICE model [15] and was applied similarly to both arms in years 1 and 2. Injection and monitoring frequencies are summarized in Table 3.

Costs

The model estimated the cost-effectiveness of ranibizumab and aflibercept treatment from the perspective of the NHS. The costs used in this analysis, and associated assumptions, are summarized in Table 4. Drug prices for ranibizumab and aflibercept were obtained from the British National Formulary [23, 24]. The costs of treatment visits and monitoring visits were derived from a previous analysis [19] and were updated to 2014 costs using the Hospital and Community Health Services inflation index [25]. The cost of blindness was associated with individuals whose BCVA was less than 35 letters (see Table S2 in the supplementary material). Future costs and health outcomes were discounted at 3.5% per annum.

Economic Analysis

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated as the ratio of the mean incremental cost and mean incremental quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for ranibizumab compared with aflibercept. Net monetary benefit (NMB) was calculated assuming the £20,000/QALY willingness-to-pay threshold recommended by NICE [26]. The NMB is equal to the incremental QALYs multiplied by the willingness-to-pay threshold of £20,000 minus the incremental cost. A NMB greater than £0 indicates that an intervention is beneficial at the threshold; a higher NMB indicates greater value. One-way sensitivity analyses were used to explore uncertainty around key inputs to the model and the effect on the resultant NMB was calculated. A sensitivity analysis was conducted on the impact of a price discount, as net drug prices are not publicly available. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was used to model joint parameter uncertainty to assess the overall uncertainty around the ICER. The probability distributions chosen for the PSA were based on those recommended for health economic analysis [27], shown in Table S3 in the supplementary material.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The analysis in this article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

Base Case Scenario

Ranibizumab was associated with a QALY gain over aflibercept of 0.0120 per patient (Table 5). Lifetime costs per patient were lower with ranibizumab (£15,273) than with aflibercept (£17,347; difference of £2074). Ranibizumab led to greater health gains at lower cost and was therefore dominant over aflibercept. The NMB was £2314 at a willingness-to-pay threshold of £20,000/QALY.

Sensitivity Analyses

The one-way sensitivity analyses showed that the model results were robust to variations in key model parameters (Fig. 2). The parameter that had the most impact was the OR for ranibizumab versus aflibercept. Using the lower end of the OR CrI (0.16), the NMB was negative (−£1145), due to fewer QALYs in the ranibizumab arm. In contrast, the NMB was positive (£11,310) at the higher end of the CrI (8.94), due to costs saved in the ranibizumab arm. Ranibizumab provided a positive NMB when a 15-year time horizon (£2239) and 1-year time horizon were assumed (£1587). When the number of injections for ranibizumab was assumed to be the same as for aflibercept in years 1 and 2, ranibizumab remained dominant (NMB of £1268). Ranibizumab provided a positive NMB (£2609) when the number of injections was assumed to be 4.8 in the first 6 months, based on the BRIGHTER trial [28] and similarly a NMB of £1805 when 5.7 injections were used, based on the BRAVO trial [10]. When similar efficacy was assumed for ranibizumab and aflibercept (i.e., an OR of 1), there were incremental savings associated with ranibizumab, with a NMB of £1929. When the OR was applied only to the proportion of patients gaining between 10 and 20 letters, the NMB was £2049. A NMB of £1436 was obtained when the price of aflibercept was assumed to be the same as ranibizumab (£742). When the price of aflibercept was assumed to be 20% lower than assumed in the base case (i.e., £653 versus £742/dose for ranibizumab), ranibizumab still provided a positive NMB (£376). Results in favor of ranibizumab over aflibercept were achieved when applying a maximum of 0.3 utility gain in the WSE (NMB of £2506), an approach consistent with the NICE technology appraisal of ranibizumab in the treatment of macular edema caused by RVO [15].

Tornado plots of one-way sensitivity analyses for ranibizumab compared with aflibercept. The range for the ranibizumab versus aflibercept OR analysis is the 95% credible interval. The NMB in the base case scenario for ranibizumab versus aflibercept is £2314. NMB net monetary benefit, OR odds ratio, WSE worse-seeing eye

The PSA showed that ranibizumab had a 62.7% probability of being cost-effective at a willingness-to-pay threshold of £20,000/QALY (Fig. 3). The cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (Fig. 4) is relatively flat due to a high proportion of simulations located in the bottom-right quadrant and upper-left quadrants; neither of these quadrants is affected by the cost-effectiveness threshold.

Discussion

Our analyses showed that, from a UK healthcare payer’s perspective, ranibizumab was dominant over aflibercept because of lower lifetime costs and higher QALY gains. The results were demonstrated to be robust by a number of one-way sensitivity analyses.

The OR from the NMA showed differences in the efficacy of ranibizumab and aflibercept, resulting in a higher probability of gaining 10 letters or more in BCVA with ranibizumab in the model. The wide CrI around the OR estimate was reflected in the PSA analysis, which showed that simulations were spread across the upper-left and bottom-right quadrants.

The main drivers of the results were the greater number of injections required and the costs of injections associated with aflibercept. Injection frequencies for ranibizumab and aflibercept in the base case scenario were taken from clinical trials, as these are the most robust estimates available, in line with approaches used in previous ranibizumab and aflibercept models [15, 29]. This is in contrast to a recent BRVO cost-effectiveness analysis submitted to the Scottish Medicines Consortium in which the treatment frequencies were assumed to be similar for ranibizumab and aflibercept [22]. Taking this into consideration, a sensitivity analysis in which the injection frequencies were assumed to be similar for the two drugs was run. Ranibizumab remained cost-effective because of lower drug costs and because fewer patients were in the low vision state (<35 letters BCVA) where they incur costs associated with blindness.

It should be noted that list drug prices were used in the base case analysis; however, NHS discounts and patient access schemes are in place for both drugs, meaning that net drug prices will be lower. A sensitivity analysis showed that ranibizumab was cost saving compared with aflibercept if the list price of aflibercept was assumed to be the same as the list price of ranibizumab. These results held when a 20% discount was applied to the list price of aflibercept. From the perspective of a UK decision maker, the net prices should be considered in the context of this analysis as a key driver of real-world cost-effectiveness.

The modeling approach used in the study is valuable in that it allows a decision maker to combine evidence from a variety of sources to derive a single assessment of the impact of the intervention on HRQoL, survival and overall treatment costs. The model was built to allow a variety of scenarios to be assessed, based on various inputs and assumptions. This is important as RVO is a complex disease, with uncertainty around the factors that should be accounted for within an assessment of the treatment pathway and the measurements that should be used. The study is of interest to UK healthcare decision makers as both treatments in the study are clinically relevant in the UK. This cost-effectiveness analysis used UK-specific data when available; this included mortality data from life tables for England and Wales, utilities derived from a UK population and cost data from UK sources such as the British National Formulary and NHS reference costs.

A limitation of the analysis is the structural application of the OR data. The OR, which is based on a gain of 15 letters or more, was applied to health states based on 10-letter or 20-letter gains. This could lead to an overestimation of the proportion of patients gaining 20 or more letters in the aflibercept arm of the model. The impact of the possible overestimation of effectiveness was addressed in the sensitivity analysis where the OR of 1.06 was conservatively applied only to the aflibercept TPs of gaining between 10 and 20 letters. Ranibizumab remained dominant in this analysis.

Another limitation is the lack of comparative efficacy data between ranibizumab and aflibercept beyond 6 months. Data from the VIBRANT trial showed that the BCVA gains observed in the first 6 months while on aflibercept were maintained at the end of year one [30]. This sustained treatment effect is also observed in the BRAVO trial [12]. The present analysis was therefore based on a conservative assumption that both treatments had equivalent efficacy after 6 months, and explored the impact of different time horizons on the results. Similarly, the rate of adverse events with ranibizumab and aflibercept was assumed to be the same. This assumption has been used in another model [19] and is supported by a systematic review of the efficacy and safety of ranibizumab, aflibercept and bevacizumab in neovascular age-related macular degeneration, which reported a similar frequency of severe adverse events for all three drugs [31].

The analysis did not include bevacizumab, a full-length anti-VEGF-A antibody developed for the treatment of cancer; bevacizumab is not licensed for the treatment of VI due to macular edema secondary to BRVO. The analysis did not compare ranibizumab with grid laser photocoagulation therapy as this has been assessed in a recent economic model which demonstrated that ranibizumab was more cost-effective [7]. The conclusions of the authors regarding the costs and health benefits of ranibizumab are in line with those of the present study; the main differences relate to the use of updated modeling approaches, as well as updated cost, utility and mortality data.

Conclusions

In this economic analysis from a UK healthcare payer’s perspective, ranibizumab was dominant over aflibercept for the treatment of macular edema secondary to BRVO, resulting in lower lifetime costs and higher QALY gains. Such evidence is valuable for formulary decision making in the UK NHS and suggests that ranibizumab should be used as the standard of care for BRVO.

References

Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Retinal vein occlusion (RVO) clinical guidelines 2015. Available from: https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Retinal-Vein-Occlusion-RVO-Guidelines-July-2015.pdf. Accessed Sept 22, 2015.

Cugati S, Wang JJ, Rochtchina E, Mitchell P. Ten-year incidence of retinal vein occlusion in an older population: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(5):726–32.

Rogers S, McIntosh RL, Cheung N, et al. The prevalence of retinal vein occlusion: pooled data from population studies from the United States, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(2):313–9.

Mitry D, Bunce C, Charteris D. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for macular oedema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;1:CD009510.

Laouri M, Chen E, Looman M, Gallagher M. The burden of disease of retinal vein occlusion: review of the literature. Eye (London). 2011;25(8):981–8.

Suner IJ, Margolis J, Ruiz K, Tran I, Lee P. Direct medical costs and resource use for treating central and branch retinal vein occlusion in commercially insured working-age and Medicare populations. Retina. 2014;34(11):2250–8.

Taylor M, Serbetci E, Ferreira A, et al. A United Kingdom-based economic evaluation of ranibizumab for patients with retinal vein occlusion (RVO). J Med Econ. 2014;17(6):423–34.

European Medicines Agency. Lucentis. Procedural steps taken and scientific information after the authorisation. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Procedural_steps_taken_and_scientific_information_after_authorisation/human/000715/WC500043552.pdf. Accessed Sept 22, 2015.

Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd. Summary of product characteristics. Lucentis 10 mg/ml solution for injection. 2014. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000715/WC500043546.pdf. Accessed Sept 22, 2015.

Campochiaro PA, Heier JS, Feiner L, et al. Ranibizumab for macular edema following branch retinal vein occlusion: six-month primary end point results of a phase III study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(6):1102–12.

Heier JS, Campochiaro PA, Yau L, et al. Ranibizumab for macular edema due to retinal vein occlusions: long-term follow-up in the HORIZON trial. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(4):802–9.

Brown DM, Campochiaro PA, Bhisitkul RB, et al. Sustained benefits from ranibizumab for macular edema following branch retinal vein occlusion: 12-month outcomes of a phase III study. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(8):1594–602.

Bayer plc. Summary of product characteristics. Eylea 40 mg/ml solution for injection in a vial. Available from: http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/27224/SPC/Eylea+40mg+ml+solution+for+injection+in+a+vial/. Accessed Sept 22, 2015.

Campochiaro PA, Clark WL, Boyer DS, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept for macular edema following branch retinal vein occlusion: the 24-week results of the VIBRANT study. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(3):538–44.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Ranibizumab for treating visual impairment caused by macular oedema secondary to retinal vein occlusion. NICE technology appraisal guidance [TA283]. Issued May 2013. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta283. Accessed Sept 22, 2015.

Regnier SA, Larsen M, Bezlyak V, Allen F. Comparative efficacy and safety of approved treatments for macular oedema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion: a network meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2015;5(6):e007527.

Klein R, Klein BE, Linton KL, De Mets DL. The Beaver Dam Eye Study: visual acuity. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(8):1310–5.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Aflibercept solution for injection for treating wet age-related macular degeneration. NICE technology appraisal guidance [TA294]. Issued July 2013. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta294. Accessed Oct 15, 2015.

Regnier SA, Malcolm W, Haig J, Xue W. Cost-effectiveness of ranibizumab versus aflibercept in the treatment of visual impairment due to diabetic macular edema: a UK healthcare perspective. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;7:235–47.

Czoski-Murray C, Carlton J, Brazier J, Young T, Papo NL, Kang HK. Valuing condition-specific health states using simulation contact lenses. Value Health. 2009;12(5):793–9.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Aflibercept for treating diabetic macular oedema. NICE technology appraisal guidance [TA346]. Issued July 2015. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta346. Accessed Oct 7, 2015.

Scottish Medicines Consortium SMC No. (1074/15). Aflibercept 40 mg/mL solution for injection (Eylea®). Available from: https://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/files/advice/aflibercept__Eylea__FINAL_August_2015Amend020915_for_website.pdf. Accessed Oct 7, 2015.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. British National Formulary price for Lucentis® (Novartis): solution for intravitreal injection, ranibizumab 10 mg/mL. Available from: http://www.evidence.nhs.uk/formulary/bnf/current/11-eye/118-miscellaneous-ophthalmic-preparations/1182-ocular-diagnostic-and-peri-operative-preparations-and-photodynamic-treatment/subfoveal-choroidal-neovascularisation/ranibizumab/lucentis. Accessed Oct 23, 2015.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. British National Formulary price for Eylea® (Bayer): solution for intravitreal injection, aflibercept 40 mg/mL. Available from: http://www.evidence.nhs.uk/formulary/bnf/current/11-eye/118-miscellaneous-ophthalmic-preparations/1182-ocular-diagnostic-and-peri-operative-preparations-and-photodynamic-treatment/subfoveal-choroidal-neovascularisation/aflibercept/eylea. Accessed Oct 26, 2015.

Hospital and Community Health Services. HCHS Pay and Prices Series 2013/14. Available from: http://www.info.doh.gov.uk/doh/finman.nsf/af3d43e36a4c8f8500256722005b77f8/e154082ca1340f1880257d71002c56a9?OpenDocument. Accessed Aug 24, 2015.

Claxton K, Martin S, Soares M, et al. Methods for the estimation of the NICE cost effectiveness threshold: revised report following referees [sic]comments. Available from: https://www.york.ac.uk/media/che/documents/reports/resubmitted_report.pdf. Accessed Sept 22, 2015.

Briggs A, Sculpher M, Claxton K. Decision modelling for health economic evaluation. Oxford: Oxford University Press on behalf of the International Epidemiological Association; 2006.

Mones JM. BRIGHTER and CRYSTAL Studies. Paper presented at: American Academy of Ophthalmology 2014 Annual Meeting; October 17–21, 2014; Chicago, Illinois.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Aflibercept for treating visual impairment caused by macular oedema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion. NICE technology appraisal guidance [TA305]. Issued February 2014. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta305. Accessed Sept 22, 2015.

Clark WL, Boyer DS, Heier JS, et al. Intravitreal aflibercept for macular edema following branch retinal vein occlusion: 52-week results of the VIBRANT study. Ophthalmology; 2015. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.09.035.

Schmid MK, Bachmann LM, Fas L, Kessels AG, Job OM, Thiel MA. Efficacy and adverse events of aflibercept, ranibizumab and bevacizumab in age-related macular degeneration: a trade-off analysis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(2):141–6.

Efficacy and safety of ranibizumab intravitreal injections versus dexamethasone intravitreal implant in patients with branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) (COMRADE-B). ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01396057. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01396057. Accessed Oct 15, 2015.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. The article processing charges and open access fee for this publication were funded by Novartis Pharma AG. Medical writing support was provided by Noelle L O’Regan PhD of PharmaGenesis London and was funded by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Disclosures

LA is an employee of Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd. CB is an employee of Novartis Ireland Limited.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The analysis in this article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Adedokun, L., Burke, C. Cost-Effectiveness of Ranibizumab Versus Aflibercept for Macular Edema Secondary to Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion: A UK Healthcare Perspective. Adv Ther 33, 116–128 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-015-0279-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-015-0279-0