Abstract

Paroxysmal positional nystagmus frequently occurs in lesions involving the cerebellum, and has been ascribed to disinhibition and enhanced canal signals during positioning due to cerebellar dysfunction. This study aims to elucidate the mechanism of central positional nystagmus (CPN) by determining the effects of baclofen on the intensity of paroxysmal positional downbeat nystagmus due to central lesions. Fifteen patients with paroxysmal downbeat CPN were subjected to manual straight head-hanging before administration of baclofen, while taking baclofen 30 mg per day for at least one week, and two weeks after discontinuation of baclofen. The maximum slow phase velocity (SPV) and time constant (TC) of the induced paroxysmal downbeat CPN were analyzed. The positional vertigo was evaluated using an 11-point numerical rating scale (0 to 10) in 9 patients. After treatment with baclofen, the median of the maximum SPV of paroxysmal downbeat CPN decreased from 30.1°/s [interquartile range (IQR) = 19.6—39.0°/s] to 15.2°/s (IQR = 11.2—22.0°/s, Wilcoxon signed rank test, p < 0.001) with the median decrement ratio at 40.2% (IQR = 28.2—50.6%). After discontinuation of baclofen, the maximum SPV re-increased to 24.6°/s (IQR = 13.1—34.4°/s, Wilcoxon signed rank test, p = 0.001) with the median increment ratio at 23.5% (IQR = 5.2—87.9%). In contrast, the TCs of paroxysmal downbeat CPN remained unchanged at approximately 3.0 s throughout the evaluation. The positional vertigo also decreased with the medication (Wilcoxon signed rank test, p = 0.020), and remained unchanged even after discontinuation of medication (Wilcoxon signed rank test, p = 0.737). The results of this study support the prior presumption that paroxysmal CPN is caused by enhanced responses of the semicircular canals during positioning due to cerebellar disinhibition. Baclofen may be tried in symptomatic patients with paroxysmal CPN.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Positional nystagmus refers to the nystagmus triggered by the changes in the dependent position of the head relative to gravity [1, 2]. According to its temporal characteristics, positional nystagmus can be divided into paroxysmal or persistent type. Either paroxysmal or persistent type of positional nystagmus may occur in central as well as peripheral vestibular lesions. Central positional nystagmus (CPN) mostly presents with apogeotropic nystagmus in the ear-down position or downbeat nystagmus after lying down or straight head-hanging (SHH) [3]. In previous studies, the paroxysmal CPN has been ascribed to disinhibition and enhanced canal signals during positioning due to cerebellar dysfunction [2, 4]. Indeed, the paroxysmal CPN mostly occurs in the planes of semicircular canals that are inhibited during the positioning, and shows the features suggestive of a semicircular canal origin regarding the latency and duration [2]. Furthermore, the intensity of paroxysmal downbeat CPN induced during SHH depends on the positioning head velocity [4]. Since the lesions having caused paroxysmal CPN were mostly overlapped in the cerebellar nodulus and uvula, disruption of GABAergic inhibition over the velocity-storage mechanism (VSM) may be presumed as the mechanism of paroxysmal CPN [2, 5]. Previously, the effect of baclofen, a GABAB receptor agonist, was evaluated in acquired pendular nystagmus and spontaneous vertical nystagmus [5, 6]. This study aims to elucidate the mechanism of CPN by determining the effects of baclofen on the intensity of paroxysmal positional downbeat nystagmus due to central lesions. We hypothesized that the intensity of induced nystagmus would decrease with the administration of baclofen and subsequently increase upon its discontinuation.

Materials and Methods

Patients

We had recruited 15 patients (11 women, mean age ± SD = 55.7 ± 13.0 years, age range = 23—73 years) with paroxysmal downbeat CPN, irrespective of the presence of positional vertigo, at the Dizziness Center of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital from September 2020 to December 2022. The median duration from the symptom (dizziness or unsteadiness) onset to evaluation was 5.0 years (IQR = 2.5—10 years, range = 0.3—13 years, Table 1). All patients underwent detailed neuro-otologic evaluation by the senior author (J.S.K). The diagnosis of paroxysmal downbeat CPN was based on (1) paroxysmal downbeat nystagmus (< 1 min) induced during SHH, (2) presence of other symptoms and signs indicative of brainstem or cerebellar dysfunction, or brainstem or cerebellar lesions documented on MRIs, and (3) no resolution of paroxysmal downbeat nystagmus with two or more application of reverse Epley or Yacovino maneuver for anterior canal benign paroxysmal positional vertigo involving the anterior semicircular canals. All patients were subjected to manual straight head-hanging (SHH) at baseline (before medication of baclofen), while taking baclofen 30 mg per day for at least one week, and two weeks after discontinuation of baclofen (Supplement Table 1). The patients themselves and their caregivers decided to participate in the study after being comprehensively informed about the potential efficacy and adverse effects of baclofen. Information was collected on demographic characteristics including age and sex, and concomitant medications such as clonazepam, gabapentin and 3–4-diaminopyridine, and the primary diagnosis from the electronic medical records.

Oculography

Eye movements were recorded binocularly at a sampling rate of 120 Hz using 3-dimensional video-oculography (VOG, SLVNG, SLMED, Seoul, South Korea). Spontaneous nystagmus was recorded both with and without visual fixation in the sitting position. Gaze-evoked nystagmus, horizontal smooth pursuit, horizontal saccades, and horizontal head-shaking nystagmus were also evaluated.

Positioning maneuvers

To ensure the effect of baclofen, the recording conditions had been controlled throughout the evaluation [7,8,9]. First, the recordings were arranged at a similar time of the day after maintaining upright position at least for one hour before the recording (Supplement Table 1). During the recording, the patients were instructed to maintain the straight ahead gaze, which was also monitored on the screen and recording traces. During the SHH, patients were laid from the sitting upright position onto the lying down position with the head extended about 30° below the table. This positioning was completed usually within 3 s (2—4 s), resulting in an average head rotation velocity of an approximately 40°/s during the positioning [4]. In each testing condition, the SHH position was maintained until the positional nystagmus disappeared or at least for one minute. The positional vertigo was assessed using an 11-point numerical rating scale (0 to 10) in 9 patients.

Analyses of Nystagmus

Digitized eye position data were analyzed with MATLAB software (version R2019b, The Math Works, Inc., MA USA). For each paroxysmal downbeat CPN, the intensity (maximum slow phase velocity, SPV) and time constant (TC) were calculated. When persistent CPN was combined with the paroxysmal one, we calculated the maximum SPV and TC of paroxysmal CPN after subtracting the persistent component from the velocity profile of induced positional nystagmus [2].

Statistical Analyses

The categorical variables are presented as the numbers and percentages, continuous variables conforming to a normal distribution as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), and the variables that are not normally distributed as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Normality of the data was determined using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Changes in the maximum SPV and TC of paroxysmal downbeat CPN and the positional vertigo after the baclofen treatment, and after discontinuation of baclofen were assessed using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. The Spearman correlation test was used to compare the maximum SPV of paroxysmal downbeat CPN with the severity of positional vertigo. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to analyze any associations of the clinical factors with the responsiveness to baclofen. For all analyses, a two-tailed p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the R software package (version 4.3.1).

Results

Clinical Characteristics

Underlying etiologies of paroxysmal downbeat CPN included spinocerebellar ataxia (n = 5, 33.3%), multiple systemic atrophy (n = 4, 26.7%), episodic ataxia (n = 1, 6.7%), Chiari malformation (n = 1, 6.7%) and paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration (n = 1, 6.7%). No etiology was identified in the remaining three patients (Table 1). Patients had dizziness (n = 15, 100%), gait ataxia (n = 13, 86.7%) and dysarthria (n = 8, 53.3%). During visual fixation, four patients (26.7%) showed spontaneous nystagmus that was pure downbeat in two, pure upbeat in one and mixed horizontal-downbeat in the remaining one. Without visual fixation in darkness, 10 patients (66.7%) showed spontaneous nystagmus that was pure downbeat in four, pure upbeat in three, pure horizontal in two, and mixed horizontal-downbeat in the remaining one. After horizontal head-shaking, 14 patients (93.3%) showed nystagmus that was mixed horizontal-downbeat in seven, pure downbeat in five, and pure horizontal in two. Ten patients (66.7%) showed gaze-evoked nystagmus, and four of them also had rebound nystagmus (Table 2). Horizontal smooth pursuit was impaired in 14 patients (93.3%). Horizontal saccades were abnormal in 12 patients (80.0%), hypermetric in 10 and hypometric in two.

During the SHH, the downbeat CPN was pure paroxysmal in 13 and mixed paroxysmal and persistent in two patients. The paroxysmal downbeat CPN reached a peak within a few seconds (median = 1.1 s, IQR = 0.8–2.8 s). After then, the nystagmus decreased exponentially.

When recruited, some patients were taking medications such as betahistine, acetazolamide, and escitalopram, which had been maintained throughout the evaluation without a change in dosage (Table 1).

Effects of Baclofen on Paroxysmal Downbeat CPN

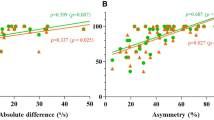

At baseline, the maximum SPV of paroxysmal downbeat CPN ranged from 7.7 to 68.1 (median = 30.1°/s, IQR = 19.6—39.0°/s). After medication of baclofen for 2–4 weeks, the maximum SPV was measured from 5.4 to 48.2 (median = 15.2°/s, IQR = 11.2—22.0°/s) with a significant decrease in the intensity (Wilcoxon signed rank test, p < 0.001). The decrement was calculated from 23.0 to 73.3% (median = 40.2%, IQR = 28.2—50.6%). After discontinuation of baclofen, the paroxysmal downbeat CPN re-increased with the median maximum SPV at 24.6°/s (IQR = 13.1—34.4°/s, Wilcoxon signed rank test, p = 0.001) and the median increment at 23.5% (IQR = 5.2—87.9%) (Figs. 1A and 2, Supplement Video). In contrast, the TCs of paroxysmal downbeat CPN remained unchanged at approximately 3.0 s throughout the evaluation (Fig. 1B).

Effects of baclofen on paroxysmal downbeat central positional nystagmus (CPN). (A) Baclofen administration resulted in a significant reduction of the maximum slow phase velocity (SPV) of paroxysmal downbeat CPN. After discontinuation of baclofen, the maximum SPV re-increased significantly. (B) The time constants of paroxysmal downbeat CPN remained unchanged throughout the evaluation

Representative recording of paroxysmal downbeat nystagmus induced during straight head-hanging in patient 7 with Chiari malformation. (A) Video-oculographic recording of eye movements shows paroxysmal downbeat positional nystagmus at baseline, during administration of baclofen, and after discontinuation of baclofen. V: vertical position of the left eye. Upward deflection denotes upward eye motion in each recording. The shaded areas in pink indicate the period of positioning. (B) Vertical slow phase velocity of the left eye in each recording. After administration of baclofen for two weeks, the maximum slow phase velocity (SPV) of induced paroxysmal downbeat nystagmus decreased from 40.4 to 10.8°/s. The maximum SPV re-increased to 31.0°/s 2 weeks after discontinuation of baclofen. In contrast, the time constants of induced paroxysmal downbeat nystagmus remained unchanged throughout the evaluation

The positional vertigo also decreased with medication (Wilcoxon signed rank test, p = 0.020), and remained unchanged even after discontinuation of medication (Wilcoxon signed rank test, p = 0.737, Fig. 3). The severity of positional vertigo did not correlate with the maximum SPV of paroxysmal downbeat CPN among the patients (Spearman correlation test, p = 0.810).

One patient (patient 10) had perioral tightness with baclofen. Univariate analyses showed no significant associations between decrements of the maximum SPV after baclofen administration and the age and sex of the patients, underlying etiology, and the duration from symptom onset to baclofen trial.

Discussion

This study documented a decrease in the maximum SPV of paroxysmal downbeat CPN with administration of baclofen, a GABAB agonist. This result supports our prior presumption that the paroxysmal CPN results from disinhibited and abnormally enhanced canal responses during positioning due to cerebellar dysfunction [2, 4].

The characteristics of paroxysmal downbeat CPN observed in this study are consistent with those of prior studies regarding its peak at onset, short duration with a TC around 3.0 s, and alignment of the nystagmus direction with the vector sum of the rotational axes of the semicircular canals that are normally inhibited during the positioning [2]. Given the lesions responsible for paroxysmal CPN located in the cerebellum, especially the nodulus and uvula, impaired cerebellar inhibition over the vestibular system is plausible as a mechanism of paroxysmal CPN [2, 10]. The irregular type of primary vestibular afferents is responsible for adaptation and the VSM of the vestibulo-ocular reflex [11, 12]. This adaptation is characterized by a rapid decline in the discharges and a rebound when the discharges go below the resting rate. And then, the discharges gradually return to the resting level. These adaptive responses are termed as the post-acceleratory secondary phenomenon [13]. The VSM plays a role in estimating the gravitational direction by integrating the rotation cues from the semicircular canal signals [14, 15]. There is a rotational feedback loop within the VSM, which acts to adjust the estimated gravitational direction to the real one. Therefore, lesions involving the vestibulocerebellum would lead to an exaggerated post-acceleratory secondary response and post-rotatory nystagmus provoked by a difference between the estimated and real gravitational directions [2, 14]. Thus, CPN may be ascribed to enhanced secondary phenomenon of the irregular afferents due to lesions involving the nodulus and uvula [2]. In our previous study, the intensity of paroxysmal downbeat CPN induced during SHH depended on the positioning head velocity [4]. This also supports that paroxysmal downbeat CPN is generated by the canal-driven signals during the positioning maneuvers.

Baclofen is a GABAB receptor agonist that enhances the inhibitory action of the vestibulocerebellum on the vestibular nuclei, and particularly inhibits the VSM of the vestibulo-ocular reflex [5, 16]. Indeed, the action of baclofen has been demonstrated by effectively inhibiting periodic alternating nystagmus, which is also ascribed to enhanced VSM due to loss of inhibition from the cerebellar nodulus and uvula [17, 18]. In patients with an acute lateral medullary infarction, baclofen suppressed head-shaking nystagmus that is also explained by asymmetry of the VSM due to unilateral interruption of the cerebellar inhibitory inputs [19]. Furthermore, baclofen can also reduce acquired spontaneous downbeat nystagmus and vertical pendular nystagmus [5, 6]. Given this background, we investigated the effects of baclofen on the intensity of paroxysmal positional downbeat nystagmus due to central lesions. This was also to ascertain our previous hypothesis on the mechanism of CPN, abnormally enhanced canal responses during positioning due to cerebellar disinhibition. Indeed, we found that baclofen reduces the intensity of paroxysmal downbeat CPN during SHH.

Notably, the reduction in the intensity of paroxysmal downbeat nystagmus after baclofen administration was not related to the underlying etiology of CPN, although the response was most pronounced in patients with spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA). Considering that all five patients with SCA showed a marked reduction (> 50%) of nystagmus, the association between the underlying etiology and baclofen effect might have been insufficiently demonstrated due to the small study population.

After administration of baclofen, the positional vertigo decreased along with reduction of positional nystagmus. However, the improved symptom persisted even after discontinuation of medication and re-increase of positional nystagmus. These findings again indicate that the severity of positional vertigo does not correlate with the intensity of positional nystagmus in central lesions, a well-established finding from the previous studies [1, 20, 21]. Otherwise, the 11-point numerical rating scale adopted in this study for grading the vertigo severity could not accurately reflect the subjective symptoms.

There are several limitations in our study. First, because of the small sample size, we were unable to perform multivariate analyses to evaluate the factors associated with the efficacy of baclofen. Second, we only quantified paroxysmal downbeat CPN, and did not include other types of paroxysmal CPN such as geotropic or apogeotropic horizontal nystagmus during head turning to either side while supine. Third, we did not consider apogeotropic benign paroxysmal positional vertigo involving the posterior canal as a rare cause of paroxysmal positional downbeat nystagmus. Finally, the long-term effect of baclofen was not evaluated in this study.

Conclusion

This study supports the prior presumption that paroxysmal CPN is caused by enhanced responses of the semicircular canals during positioning due to cerebellar disinhibition. Baclofen may be a safe and effective treatment option for patients with symptoms due to paroxysmal downbeat CPN regardless of the underlying etiologies. Future clinical trials involving a larger number of patients are required to validate the efficacy of baclofen and identify the optimal dose and duration of medication.

Data Availability

Anonymized data will be shared upon request form any qualified investigator.

References

Buttner U, Helmchen C, Brandt T. Diagnostic criteria for central versus peripheral positioning nystagmus and vertigo: a review. Acta Otolaryngol. 1999;119:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016489950181855.

Choi JY, Kim JH, Kim HJ, Glasauer S, Kim JS. Central paroxysmal positional nystagmus: Characteristics and possible mechanisms. Neurology. 2015;84:2238–46. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001640.

Choi J, Kim JS. Advances in translational neuroscience of eye movement disorders. Springer; 2019.

Ling X, Kim HJ, Lee JH, Choi JY, Yang X, Kim JS. Positioning velocity matters in central paroxysmal positional vertigo: implication for the mechanism. Front Neurol. 2020;11:591602. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.591602.

Dieterich M, Straube A, Brandt T, Paulus W, Buttner U. The effects of baclofen and cholinergic drugs on upbeat and downbeat nystagmus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54:627–32. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.54.7.627.

Averbuch-Heller L, Tusa RJ, Fuhry L, Rottach KG, Ganser GL, Heide W, Buttner U, Leigh RJ. A double-blind controlled study of gabapentin and baclofen as treatment for acquired nystagmus. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:818–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410410620.

Spiegel R, Rettinger N, Kalla R, Lehnen N, Straumann D, Brandt T, Glasauer S, Strupp M. The intensity of downbeat nystagmus during daytime. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1164:293–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03865.x.

Marti S, Palla A, Straumann D. Gravity dependence of ocular drift in patients with cerebellar downbeat nystagmus. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:712–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.10370.

Spiegel R, Kalla R, Rettinger N, Schneider E, Straumann D, Marti S, Glasauer S, Brandt T, Strupp M. Head position during resting modifies spontaneous daytime decrease of downbeat nystagmus. Neurology. 2010;75:1928–32. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181feb22f.

Fernandez C, Alzate R, Lindsay JR. Experimental observations on postural nystagmus. II. Lesions of the nodulus. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1960;69:94–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/000348946006900108.

Angelaki DE, Perachio AA. Contribution of irregular semicircular canal afferents to the horizontal vestibuloocular response during constant velocity rotation. J Neurophysiol. 1993;69:996–9. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.1993.69.3.996.

Clendaniel RA, Lasker DM, Minor LB. Horizontal vestibuloocular reflex evoked by high-acceleration rotations in the squirrel monkey. IV. Responses after spectacle-induced adaptation. J Neurophysiol. 2001;86:1594–611. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.2001.86.4.1594.

Goldberg JM, Fernandez C. Physiology of peripheral neurons innervating semicircular canals of the squirrel monkey. 3. Variations among units in their discharge properties. J Neurophysiol. 1971;34:676–84. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.1971.34.4.676.

Laurens J, Angelaki DE. The functional significance of velocity storage and its dependence on gravity. Exp Brain Res. 2011;210:407–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-011-2568-4.

Merfeld DM, Zupan L, Peterka RJ. Humans use internal models to estimate gravity and linear acceleration. Nature. 1999;398:615–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/19303.

Cohen B, Helwig D, Raphan T. Baclofen and velocity storage: a model of the effects of the drug on the vestibulo-ocular reflex in the rhesus monkey. J Physiol. 1987;393:703–25. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016849.

Leigh RJ, Averbuch-Heller L, Tomsak RL, Remler BF, Yaniglos SS, Dell’Osso LF. Treatment of abnormal eye movements that impair vision: strategies based on current concepts of physiology and pharmacology. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:129–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410360204.

Waespe W, Cohen B, Raphan T. Dynamic modification of the vestibulo-ocular reflex by the nodulus and uvula. Science. 1985;228:199–202. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3871968.

Choi KD, Oh SY, Park SH, Kim JH, Koo JW, Kim JS. Head-shaking nystagmus in lateral medullary infarction: patterns and possible mechanisms. Neurology. 2007;68:1337–44. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000260224.60943.c2.

Choi JY, Glasauer S, Kim JH, Zee DS, Kim JS. Characteristics and mechanism of apogeotropic central positional nystagmus. Brain. 2018;141:762–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awx381.

Bertholon P, Bronstein AM, Davies RA, Rudge P, Thilo KV. Positional down beating nystagmus in 50 patients: cerebellar disorders and possible anterior semicircular canalithiasis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:366–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.72.3.366.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the patients who participated to the study.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Seoul National University. This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (No. NRF-2021R1F1A1063826).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S-YY acquired and analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. J-YC, H-JK and J-HL acquired and analyzed the data. H-JK analyzed and interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. J-SK designed and conceptualized the study, interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. J.S. Kim serves as an associate editor of Frontiers in Neuro-otology and on the editorial boards of the Journal of Korean Society of Clinical Neurophysiology, the Journal of Clinical Neurology, Frontiers in Neuro-ophthalmology, the Journal of Neuro-ophthalmology, the Journal of Vestibular Research, and Clinical and Translational Neuroscience. Dr. J.Y. Choi serves as an associate editor of the Journal of Clinical Neurology. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB No. B-1903–528-102). The patient and participants (technicians for video-oculography) in supplementary video provided the informed consents to publish.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file2 (MP4 115860 KB) Straight head-hanging induced paroxysmal downbeat central positional nystagmus in patient 7 with Chiari malformation. At baseline (before administration of baclofen) → During administration of baclofen for two weeks → two weeks after discontinuation of baclofen

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yun, SY., Lee, JH., Kim, HJ. et al. Effects of Baclofen on Central Paroxysmal Positional Downbeat Nystagmus. Cerebellum (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-024-01684-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12311-024-01684-z