Abstract

Background

Although leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) is often idiopathic or secondary to benign diseases, it sometimes accompanies malignancies. Besides being more common in hematological cancers compared to solid tumors, the association of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) with LCV is extremely rare.

Case report

In this study, we present a 22-year-old woman presenting with palpable petechiae, purpura, and ecchymoses on her limbs. Bone marrow and skin biopsy of the patient with bicytopenia revealed precursor B cell ALL and LCV, respectively.

Conclusion

This case is the first adult ALL case with paraneoplastic LCV. In this study, it is emphasized that hematological malignancies should be considered in patients presenting with cutaneous vasculitis, especially in the presence of cytopenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) is a histopathological definition and is characterized by inflammation in small vessels of the skin and the breakdown of neutrophils [1]. Cutaneous vasculitis can present in different ways: (a) as cutaneous component of systemic vasculitis, (b) as skin-limited or skin-dominant variant of systemic vasculitis, and (c) as single organ vasculitis of the skin [2]. Although single-organ vasculitis of the skin is more often idiopathic, it can also develop secondary to many causes such as drugs, infections, connective tissue diseases, and malignancies. Paraneoplastic cutaneous vasculitis occurs at a rate of 3.8% and is more common in hematological malignancies than in solid tumors [3]. To our knowledge, the patient we present is the first adult case of ALL with paraneoplastic LCV.

Case presentation

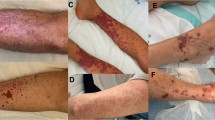

A 22-year-old woman presented with acute complaints of erythematous rashes on the extremities. The patient did not have weight loss, night sweats, myalgia, arthralgia, hematuria, abdominal pain, diarrhea, melena, chest pain, cough, dyspnea, hemoptysis, sputum, nor dysuria. She had no previously known illness, allergies, history of any drug use, a family history of malignancy nor rheumatological disease, and did not smoke. On physical examination, non-blanching palpable purpura, petechiae, and ecchymoses were detected on the forearms and legs (Fig. 1a). There was no lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly and other system examinations were normal. In laboratory investigation, hemoglobin concentration was 8 g/dL (11.7–15.5), leukocyte count was 1.1 × 103/μL (4.1–11.2 × 103) with 51.9% lymphocytes, 2.2% monocytes, 44.9% neutrophils, and 0.3% eosinophils, and platelet count was 160 × 103/μL (159–388 × 103). There was no abnormality in liver and kidney function tests and complete urine analysis. Serology for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) were negative. Rheumatoid factor (RF) was 34.2 IU/mL (0–20), anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) test was positive with 1:160 titer speckled pattern, C3 and C4 were normal, cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP), anti-dsDNA, anti-Sm, anti-Ro, anti-La, anti-Jo-1, anti-Scl-70, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) were negative.

The patient underwent bone marrow aspiration biopsy and a punch biopsy of the skin from ecchymotic lesions on the leg. Skin biopsy revealed fibrin deposition in superficial small vessels in the dermis, vascular wall destruction, erythrocyte extravasation, and leukocytoclasia (Fig. 2). In the direct immunofluorescence examination, perivascular C3 and IgM were positive and IgA and IgG were negative. The diagnosis of LCV was made. Bone marrow biopsy revealed hypercellular marrow tissue with diffuse blastic infiltration (Fig. 3). In immunohistochemical examination, blastic cells were positive with CD34, terminal deoxynucleotide transferase (TdT), and CD19 and focally positive with CD10. The findings were consistent with precursor B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). In the flow cytometry, CD10 (64%), CD19 (97%), cCD79a (50%), and TdT (45%) were positive. Bone marrow cytogenetics revealed a normal 46,XX female karyotype.

Brain, neck, thorax, and abdominal computed tomography (CT) examinations revealed no pathological findings. There was no central nervous system (CNS) involvement on cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) examination.

Induction chemotherapy with the pediatric ALL regimen BFM-95 IA was instituted with vincristine, daunorubicine, prednisone, and asparaginase as well as intrathecal methotrexate [4]. Significant improvement was observed in skin lesions within 3 weeks after first induction regimen (Fig. 1b). She achieved complete remission with minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity, and we started second-phase induction protocol BFM-95 IB consisting of cyclophosphamide, cytarabine, mercaptopurine, and intrathecal methotrexate.

Discussion

In 1986, McLean described two criteria for the identification of paraneoplastic vasculitis: first, the simultaneous occurrence of vasculitis and neoplasia; and second, their parallel course [5]. Cutaneous LCV is the most common paraneoplastic vasculitis with a rate of 43–45%, and it is more common in hematological malignancies than in solid tumors [6, 7]. There are cases reported with many hematological malignancies, such as acute myeloid leukemia (AML), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), hairy cell leukemia, lymphomas, multiple myeloma, and myeloproliferative diseases [8,9,10,11]. But paraneoplastic cutaneous vasculitis in ALL is extremely rare and has been previously reported only in an 11-year-old girl [12]. To the best of our knowledge, our patient is the first adult ALL case with paraneoplastic LCV.

The exact mechanism of the development of paraneoplastic vasculitis is not yet known. In 1986, Longley et al. initially suggested that malignant neoplasms can produce antigens, causing paraneoplastic vasculitis [13]. Besides this, several possible mechanisms have been suggested such as impaired clearance of normally produced immune complexes and production of antibodies directed toward endothelial antigens [3]. Infections are common in patients with cancer, and it can be a confusing factor in understanding the relationship between vasculitis and malignancy. In one study, confounding factors such as infection, drug reactions, and cryoglobulin deposition were detected in 39% of cases [11].

In most cases, cancer treatment also improves paraneoplastic vasculitis. When curative treatment cannot be applied, glucocorticoids or other immunosuppressive agents may be needed for vasculitis treatment [3]. In our patient, improvement of cutaneous lesions was observed within 3 weeks after BFM-95 chemotherapy was commenced.

Paraneoplastic vasculitis is diagnosed simultaneously with malignancies in 38% of cases [3, 7]. Histopathologically, LCV constitutes the vast majority of paraneoplastic cutaneous vasculitis, and this is important especially in the initial diagnosis. Our case highlights that in cases with cutaneous LCV, clinicians should be aware that this may accompany hematological malignancies, especially in the presence of cytopenias.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

Carlson JA, Ng BT, Chen K (2005) Cutaneous vasculitis update: diagnostic criteria, classification, epidemiology, etiology, pathogenesis, evaluation and prognosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 27(6):504–528

Sunderkötter CH, Zelger B, Chen KR, Requena L, Piette W, Carlson JA et al (2018) Nomenclature of cutaneous vasculitis: dermatologic addendum to the 2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheumatol. 70(2):171–184

Loricera J, Calvo-Río V, Ortiz-Sanjuán F, González-López MA, Fernández-Llaca H, Rueda-Gotor J et al (2013) The spectrum of paraneoplastic cutaneous vasculitis in a defined population: incidence and clinical features. Med (United States). 92(6):331–343

Avramis VI, Sencer S, Periclou AP, Sather H, Bostrom BC, Cohen LJ et al (2002) A randomized comparison of native Escherichia coli asparaginase and polyethylene glycol conjugated asparaginase for treatment of children with newly diagnosed standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a Children’s Cancer Group study. Blood. 99(6):1986–1994

McLean DI (1986) Cutaneous paraneoplastic syndromes. Arch Dermatol. 122:765–767

Kurzrock R, Cohen PR (1993) Vasculitis and cancer. Clin Dermatol. 11(1):175–187

Fain O, Hamidou M, Cacoub P, Godeau B, Wechsler B, Pariès J et al (2007) Vasculitides associated with malignancies: analysis of sixty patients. Arthritis Care Res. 57(8):1473–1480

Jayachandran NV, Thomas J, Chandrasekhara PKS, Kanchinadham S, Kadel JK, Narsimulu G (2009) Cutaneous vasculitis as a presenting manifestation of acute myeloid leukemia. Int J Rheum Dis. 12(1):70–73

Lulla P, Bandeali S, Baker K (2011) Fatal paraneoplastic systemic leukocytoclastic vasculitis as a presenting feature of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Lymphoma. Myeloma Leuk 11(SUPPL.1):S14–S16

Moyers JT, Liu LW, Ossowski S, Goddard L, Kamal MO, Cao H (2019) A rash in a hairy situation: leukocytoclastic vasculitis at presentation of hairy cell leukemia. Am J Hematol. 94(12):1433–1434

Bachmeyer C, Wetterwald E, Aractingi S (2005) Cutaneous vasculitis in the course of hematologic malignancies. Dermatology. 210(1):8–14

Jaing TH, Hsueh C, Chiu CH, Shih IH, Chan CK, Hung IJ (2002) Cutaneous lymphocytic vasculitis as the presenting feature of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 24(7):555–557

Longley S, Caldwell JR, Panush RS (1986) Paraneoplastic vasculitis. Unique syndrome of cutaneous angiitis and arthritis associated with myeloproliferative disorders. Am J Med. 80(6):1027–1030

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable

Consent to participate

Written informed consent for participation of their details was obtained from the patient.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of their details was obtained from the patient.

Code availability

Not applicable

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ismayilov, R., Haziyev, T., Ozdemir, D.A. et al. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis as a previously unreported paraneoplastic manifestation of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. J Hematopathol 13, 265–268 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12308-020-00416-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12308-020-00416-6