Abstract

Chronic low back pain (LBP) represents a leading cause of absenteeism from work. An accurate knowledge of complex interactions is essential in understanding the difficulties of return to work (RTW) experienced by workers affected by chronic LBP. This study aims to identify factors related to chronic LBP, the worker, and the psycho-social environment that could predict and influence the duration of an episode of sick leave due to chronic LBP.Studies reporting the relation between prognostic factors and absenteeism from work in patients with LBP were included. The selected studies were grouped by prognostic factors. The results were measured in absolute terms, relative terms, survival curve, or duration of sick leave. The level of evidence was defined by examining the quality and the appropriateness of findings across studies in terms of significance and direction of relationship for each prognostic factor.A total of 20 studies were included. Prognostic factors were classified in clinical, psycho-social, and social workplace, reaching a total of 31 constructs. Global conditions with less favorable repercussions on worker’s lives resulted in a delay in time to RTW. Older age, female, higher pain or disability, depression, higher physical work demands, and abuse of smoke and alcohol have shown strong level of evidence for negative outcomes.High global health well-being, great socioeconomic status, and good mental health conditions are decisive in RTW outcomes. Interventions that aim at RTW of employee’s sick-listed with LBP should focus on psycho-social aspects, health behaviors, and workplace characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is considered a global public health problem, representing one of the most causes of absenteeism from work. In particular, the annual productivity losses from missed workdays due to LBP are estimated at $28 billion in the USA alone, and this condition currently represents the main cause of disability, affecting nearly 600 million workers worldwide [1]. LBP is the third most common cause of years lived with disability (YLDs) worldwide, accounting for nearly 10% of all YLDs [2]. Despite developments in objective health measures, time of absenteeism from work due to LBP has also shown an increase in European countries [3, 4]. Reasons underlying this situation include degree of disease severity, different types of treatments, compliance with the interventions, but also lifestyle risk factors and characteristics of the patient’s work activities. In detail, the occupational risk factors that may be involved in the etiopathogenesis of LBP are numerous and include manual handling of heavy loads, awkward and prolonged postures, whole-body mechanical vibrations, and work-related stress [5]. Therefore, when the work activities required by the specific job carried out by the patient with LBP involve exposure to these occupational risk factors, an increase in absenteeism and a delayed return to work (RTW) often occur [6]. Consequently, an accurate and well-rounded knowledge of the complex interactions between workers health conditions, psychosocial factors and workplace issues is essential in understanding the difficulties of returning to work experienced by workers affected by chronic LBP [7]. Indeed, RTW represents a multifactorial process influenced by physical, psychological, and social factors, and provides a reliable description of work success and socioeconomic status worldwide [8]. Subjects unable to RTW because of chronic injury or illness can experience greater physical ailments and poorer psycho-social adjustment (increased anxiety, depression, social isolation) [9, 10]. Current literature data widely show that recovery beliefs, pain-related behaviors, work-related risk factors, and health-related conditions must be assessed as potential influencers of RTW [11,12,13]. In this regard, several studies have tried to identify risk factors for absenteeism from work correlated to LBP [14, 15]. However, their findings do not allow to obtain definitive conclusions on elements or parameters to considered to achieve an early RTW of workers with LBP. In fact, most observational studies focusing on pain and RTW have mainly paid attention to acute LBP [16]. The aim of this study is to identify factors related to LBP, the worker, the job, and the psycho-social environment, that could predict and influence the duration of an episode of sick leave and time away from work due to chronic LBP.

Materials and methods

Definition of prognostic factors and outcomes

Low back pain must be considered a multifactorial problem. Individual, psycho-social, and work-related factors seem to influence its onset, duration, and outcome. Several predictive factors have been identified, including every aspect of personal life, job and workplace, psychological environment, and specific low back pain characteristics of patients. Therefore, this review focused on the time away from work, defined both as “sick leave” and “return to work”.

Literature review

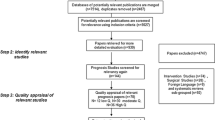

This review was assessed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. The search strategy was conducted on PubMed, MEDLINE, Cochrane, and Scopus databases. The following string was used: (((“low back pain”[MeSH Terms] OR (“low”[All Fields] AND “back”[All Fields] AND “pain”[All Fields]) OR “low back pain”[All Fields]) AND (“return to work”[MeSH Terms] OR (“return”[All Fields] AND “work”[All Fields]) OR “return to work”[All Fields])) OR (“low back pain”[MeSH Terms] OR (“low”[All Fields] AND “back”[All Fields] AND “pain”[All Fields]) OR “low back pain”[All Fields])) AND (“sick leave”[MeSH Terms] OR (“sick”[All Fields] AND “leave”[All Fields]) OR “sick leave”[All Fields]). The reviewers conducted the last investigation on 31st May 2023. Two autonomous researchers (G.S. and F.R.) independently performed the search. Every study has initially been chosen by utilizing title and abstract, and duplicate studies were removed. Then, they consulted the full-text article and performed an accurate reading of every chosen research, obtaining data to reduce selection bias. A cross-reference exploration of the studies was made to get additional related research. Every study describing any prognostic factors related to absenteeism from work due to LBP was considered.

Inclusion criteria

Studies published from 2012 to May 2023 involving patients with an episode of LBP and sick leave, with a duration of more than 12 weeks, reporting the relation between at least one prognostic factor and absenteeism to work were included. Moreover, the results had to be measured in absolute terms (rate), relative terms (odds ratio, rate ratio, hazard ratio), survival curve, or duration of sick leave. Studies antecedents to 2012, systematic reviews and studies concerning the acute and subacute LBP were excluded.

Quality assessment

Two independent investigators (G.S. and F.R.) scored the quality of included studies. Studies evaluation was performed by the quality assessment list composed of 17 items, organized into three categories: methodological quality, quality of measurement of prognostic factors, and statistical quality [17]. Items were the following: adequate description of the study population, description of response, the extent and length of follow-up, an explicit definition of time to RTW, the number of prognostic factors measured, and the quality of data presentation. The maximum score for all items was 17. Studies were at high quality (range 12–17 points), moderate quality (range 9–11 points), or low quality ( < 9 points).

Data extraction

Information concerning the definition of prognostic factor, outcomes, country, setting, association estimate, and sample size were extracted from each article. For the risk of no RTW, a ratio larger than one was considered significative of delay in time until RTW.

Level of evidence

The selected studies were grouped by prognostic factors. The level of evidence was defined by examining the quality of each study and the appropriateness of findings across studies in terms of significance and direction of relationship for each prognostic factor. In particular, the level of evidence has been identified by the following criteria:

-

Strong evidence when prognostic factors appeared in multiple high-quality studies.

-

Moderate evidence when prognostic factors appeared in one high-quality study and one or lower-quality studies or multiple lower-quality studies.

-

Insufficient evidence when prognostic factors appeared in only one study available or several studies with inconsistent findings.

Results

Literature search

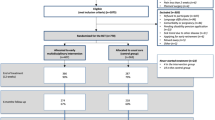

From the initial research, 1091 articles were obtained, of which 279 were removed as duplicates. After screening all titles and abstracts, 46 articles were identified as suitable for a more full-text review. Finally, 20 publications satisfied all the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Studies characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Quality assessment

The mean quality score was 11.8, ranging from 7 to 15 (Table 2). The quality of thirteen studies (72%) was high, while three (17%) studies were of moderate quality, and two (11%) were of low quality.

Evidence on prognostic factors

The identified prognostic factors were classified into three categories: clinical, psycho-social, and social workplace. Each category included factors or tools measuring the same or very similar findings, reaching a total of 31 constructs. The level of evidence for each prognostic factor is reported in Table 3.

Results on clinical prognostic factors

There is evidence of a positive association between male sex and RTW from 4 high-quality and 2 low-quality studies.

There is high evidence of a positive association between younger and RTW from 4 high-quality and 2 low-quality studies.

Diagnosis has a moderate level of evidence, showing a significant association with RTW only in one high-level study. There is high evidence of the association between comorbidities and RTW, resulting from 4 high-quality studies. In particular, the more diseases a patient suffers from, the greater the risk of delaying the return to work.

Radiating pain was studied in none of the chosen studies. There is high evidence that pain intensity has a negative association with RTW from 7 high-quality studies. Functional status shows a high level of evidence in its association with RTW, resulting in statistically significant in 5 high-quality studies and one low quality.

A delay in referral to intervention showed a strong association with a delay in RTW. This high level of evidence was confirmed by 5 high-quality studies and one lower quality study. Only in one low-quality study the early intervention directly compared with an ordinary waiting list did not significantly affect the RTW.

Both health and lifestyle related clinical factors have a moderate level of evidence measures on RTW from only one high-quality study. Notably, being a smoker and exceeding in alcohol assumption have shown a strong association with a delay RTW, respectively, from 4 and 2 high-quality studies.

Results on personal psycho-social factors

Researchers from three studies reported differently on the one-item question from the workability index that investigates expectations of RTW. These studies have shown a strong level of evidence for the high recovery expectation and RTW.

Pain catastrophizing, fear avoidance, coping, and kinesiophobia presented all a high level of evidence on RTW. Pain catastrophizing and fear-avoidance have been considered in most of the studies, resulting in a positive association with RTW respectively in 6 and 5 high-quality articles. Also, kinesiophobia and coping resulted in a positive statistically significant association with RTW, despite being measured in a limited number of studies. Only one high-quality study and one low-quality study reported a positive association for coping and 3 high-quality studies for kinesiophobia.

Six high-quality studies assessed the association between mental health and RTW, resulting in a strong level of positive evidence between high mental health status and an early RTW. At the opposite side, distress, depression, and disability have shown a negative relationship with RTW. Notably, these results confirm that global mental well-being has an essential influence on the time of absenteeism from work.

In only one high-quality study, cognitive appraisal has shown an association with RTW, resulting in a moderate level of evidence. Three high-quality studies found a strong correlation between disability education and RTW.

Results on social workplace prognostic factors

Each of the social workplace prognostic factors analyzed has revealed a high level of evidence on RTW. All these factors are reported in a single category to underlying the strong correlation among each of them. Workers compensation has been evaluated in one high-quality study, showing a moderate level of evidence.

Discussion

This study aims to identify factors that predict the duration of time away from work at the chronic stage of LBP. The factors able to influence RTW are related to LBP, worker, and job characteristics, as well as to the psycho-social environment. Accurate comprehension of the risk factors related to absenteeism from work is essential to drive practitioners in their interaction with patients during the RTW process. Our results showed that prognostic factors within the clinical, psycho-social, and social workplace categories are all associated with RTW. Overall, prognostic factors related to high global health well-being, great socioeconomic status, good mental health conditions have been positively associated with RTW outcomes. In the same way, global conditions with less favorable repercussions on workers lives resulted in a delay in time to RTW. Among these were older age, being female, higher pain or disability, depression, higher physical work demands, abuse of smoke and alcohol have shown a strong level of evidence for negative outcomes. Therefore, health and social condition are decisive in RTW outcomes. Our findings confirmed the results of Steensa et al. [38] and Cancelliere et al. [7], from whose research health global status seemed not to influence absenteeism from work. Interestingly, our results also highlighted the crucial role of interventions in the workplace environment since all factors included in this category have strongly influenced RTW. Therefore, occupational physicians (OPs) can play a crucial function also in the context of RTW. In fact, they not only are a fundamental component within the Occupational Safety and Health (OSH) management systems in protecting and improving the health of employees, but these professional figures are also increasingly asked to address issues such as health promotion and occupational rehabilitation in addition to protecting the worker’s health against work-related injuries and occupational diseases [39]. In this regard, OPs have available various resources and operational strategies to facilitate the RTW of a worker with LBP. For example, they could raise workers awareness of occupational risk factors to prevent work-related injuries or disabling conditions and promote best practices in order to foster employee physical and psychological well-being [40]. Moreover, the main task of OPs is to assess the fitness of workers for specific tasks, ensuring a satisfactory fit between person and job, enabling workers to undertake the work they have been selected to perform safely and effectively [41]. However, the best result in terms of efficient and timely RTW can only be achieved by developing a multidisciplinary vocational rehabilitation program that includes the involvement, in addition to OPs, also of other professional figures such as the orthopaedist, physiotherapist, neurosurgeon, nutritionist and psychologist [41, 42]. One of the essential points of this research is the identification of eventual modifiable prognostic factors because these could respond to new interventions targeted at modifying them, improving RTW outcomes. The expectations of recovery, pain intensity, and disability levels, as well as depression, distress, and workplace factors, can be considered among the most important modifiable factors in progressing RTW across health and injury conditions. For example, having hopeful expectations for recovery and RTW was usually correlated with positive RTW outcomes, as shown by evidence from mental health studies. Instead, for people who expected to recover more slowly after an injury, this often happened. This mental condition can lead to a slower recovery and a higher risk of receiving sick leave benefits. But since it is considered a modifiable prognostic factor, it should be early identified. Despite recovery expectations would seem correlated to mental health status, current research has not confirmed this association. Gatchel et al. [36] had shown that neither type nor the degree of psychopathology were significantly predictive of a patient’s ability to return to work successfully. Other important modifiable prognostic factors are those concerning workplace environment conditions. Work accommodation seems to be essential for increasing RTW outcomes, especially across health and injury conditions. Moreover, the opportunity to adopt special accommodations for workers who have suffered an injury/illness or who have acquired a disability condition—and are exposed to specific occupational risk factors—is widely recognized and derives from the need to guarantee a full and satisfactory fit between worker’s health conditions and characteristics of working tasks and activities [43]. Once again, the implementation of an adequate occupational rehabilitation program by the OSH management systems could play a key role in evaluating and identifying the most suitable accommodations to be taken by employers for LBP workers, but also in supporting them with specific and targeted counseling programs and strategies. The present study has several strengths as well as limitations. First, our analysis is restricted to studies with a defined phase of disease, as chronic LBP. In most of the current articles, patients are enrolled in different points of their disease, creating a mixture of the population with workers on sick leave and workers still at work. However, the cut-off for identifying the chronic phase of disease was chosen at 12 weeks based on the median and 75th percentile. Moreover, due to the large number of prognostic factors analyzed, heterogeneous methods in which data are collected have been found, and this may influence the robustness of the results. Therefore, the included studies are still not enough to justify a definitive association between prognostic risk factors and RTW, and further specific studies, with more homogeneous evaluation, should be performed to define these factors definitively.

Conclusion

This review proved that multidisciplinary interventions should be performed to improve RTW outcomes. A deeper knowledge of the possible causes which delay return to work can provide essential solutions to improved workers condition and productivity annual losses for absenteeism. In particular, high global health well-being, great socioeconomic status, and good mental health conditions are decisive in RTW outcomes. In conclusion, interventions that aim at return-to-work of employees sick-listed with LBP should predominantly focus on psycho-social aspects, health behaviors, and workplace characteristics.

References

Rashid M, Kristofferzon M-L, Nilsson A, Heiden M (2017) Factors associated with return to work among people on work absence due to long-term neck or back pain: a narrative systematic review. BMJ Open 7:e014939. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014939

Wu A, March L, Zheng X et al (2020) Global low back pain prevalence and years lived with disability from 1990 to 2017: estimates from the global burden of disease study 2017. Ann Transl Med 8:299–299. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2020.02.175

Ahrberg Y, Landstad BJ, Bergroth A, Ekholm J (2010) Desire, longing and vanity: emotions behind successful return to work for women on long-term sick leave. Work 37:167–177. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-2010-1067

Waddell G (2006) Preventing incapacity in people with musculoskeletal disorders. Br Med Bull 77–78:55–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldl008

Russo F, Papalia GF, Vadalà G et al (2021) The effects of workplace interventions on low back pain in workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:12614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312614

Serranheira F, Sousa-Uva M, Heranz F et al (2020) Low back pain (LBP), work and absenteeism. Work 65:463–469. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-203073

Cancelliere C, Donovan J, Stochkendahl MJ et al (2016) Factors affecting return to work after injury or illness: best evidence synthesis of systematic reviews. Chiropr Man Ther 24:32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-016-0113-z

Hlobil H, Staal JB, Spoelstra M et al (2005) Effectiveness of a return-to-work intervention for subacute low-back pain. Scand J Work Environ Health 31:249–257. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.880

Hoffman BM, Papas RK, Chatkoff DK, Kerns RD (2007) Meta-analysis of psychological interventions for chronic low back pain. Health Psychol 26:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.1

Iles RA, Davidson M, Taylor NF (2007) Psychosocial predictors of failure to return to work in non-chronic non-specific low back pain: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med 65:507–517. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2007.036046

Alexopoulos EC, Konstantinou EC, Bakoyannis G et al (2008) Risk factors for sickness absence due to low back pain and prognostic factors for return to work in a cohort of shipyard workers. Eur Spine J 17:1185–1192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-008-0711-0

Heymans MW, de Vet HCW, Knol DL et al (2006) Workers beliefs and expectations affect return to work over 12 months. J Occup Rehabil 16:685–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-006-9058-8

Hagen EM, Svensen E, Eriksen HR (2005) Predictors and modifiers of treatment effect influencing sick leave in subacute low back pain patients. Spine 30:2717–2723. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000190394.05359.c7

Alexanderson KAE, Borg KE, Hensing GKE (2005) Sickness absence with low-back, shoulder, or neck diagnoses: an 11-year follow-up regarding gender differences in sickness absence and disability pension. Work Read Mass 25:115–124

Storheim K, Ivar Brox J, Holm I, Bø K (2005) Predictors of return to work in patients sick listed for sub-acute low back pain: a 12-month follow-up study. J Rehabil Med 37:365–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/16501970510040344

Fritz JM, Wainner RS, Hicks GE (2000) The use of nonorganic signs and symptoms as a screening tool for return-to-work in patients with acute low back pain. Spine 25:1925–1931. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200008010-00010

Steenstra IA (2005) Prognostic factors for duration of sick leave in patients sick listed with acute low back pain: a systematic review of the literature. Occup Environ Med 62:851–860. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2004.015842

Opsahl J, Eriksen HR, Tveito TH (2016) Do expectancies of return to work and job satisfaction predict actual return to work in workers with long lasting LBP? BMC Musculoskelet Disord 17:481. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1314-2

Besen E, Young AE, Shaw WS (2015) Returning to work following low back pain: towards a model of individual psychosocial factors. J Occup Rehabil 25:25–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-014-9522-9

Jensen OK, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Jensen C, Nielsen CV (2013) Prediction model for unsuccessful return to work after hospital-based intervention in low back pain patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 14:140. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-14-140

Norbye AD, Omdal AV, Nygaard ME et al (2016) Do patients with chronic low back pain benefit from early intervention regarding absence from work?: A randomized, controlled, single-center pilot study. Spine 41:E1257–E1264. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000001878

Macías-Toronjo I, Sánchez-Ramos JL, Rojas-Ocaña MJ, García-Navarro EB (2020) Influence of psychosocial and sociodemographic variables on sickness leave and disability in patients with work-related neck and low back pain. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:5966. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165966

Leung GCN, Cheung PWH, Lau G et al (2021) Multidisciplinary programme for rehabilitation of chronic low back pain–factors predicting successful return to work. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22:251. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04122-x

Carregaro RL, Tottoli CR, da Rodrigues DS et al (2020) Low back pain should be considered a health and research priority in Brazil: lost productivity and healthcare costs between 2012 to 2016. PLoS ONE 15:e0230902. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230902

Lardon A, Dubois J-D, Cantin V et al (2018) Predictors of disability and absenteeism in workers with non-specific low back pain: a longitudinal 15-month study. Appl Ergon 68:176–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2017.11.011

Trinderup JS, Fisker A, Juhl CB, Petersen T (2018) Fear avoidance beliefs as a predictor for long-term sick leave, disability and pain in patients with chronic low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 19:431. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-018-2351-9

Macías-Toronjo I, Rojas-Ocaña MJ, Sánchez-Ramos JL, García-Navarro EB (2020) Pain catastrophizing, kinesiophobia and fear-avoidance in non-specific work-related low-back pain as predictors of sickness absence. PLoS ONE 15:e0242994. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242994

Koopman FS, Edelaar M, Slikker R et al (2004) Effectiveness of a multidisciplinary occupational training program for chronic low back pain: a prospective cohort study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 83:94–103. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PHM.0000107482.35803.11

Gauthier N, Sullivan MJL, Adams H et al (2006) Investigating risk factors for chronicity: the importance of distinguishing between return-to-work status and self-report measures of disability. J Occup Environ Med 48:312–318. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jom.0000184870.81120.49

Vendrig AA (1999) Prognostic factors and treatment-related changes associated with return to work in the multimodal treatment of chronic back pain. J Behav Med 22(3):217–232. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1018716406511

Okurowski L, Pransky G, Webster B et al (2003) Prediction of prolonged work disability in occupational low-back pain based on nurse case management data. J Occup Environ Med 45:763–770. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.jom.0000079086.95532.e9

van der Giezen AM, Bouter LM, Nijhuis FJN (2000) Prediction of return-to-work of low back pain patients sicklisted for 3–4 months. Pain 87:285–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00292-X

Hansson TH, Hansson EK (2000) The effects of common medical interventions on pain, back function, and work resumption in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine 25(23):3055–3064. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200012010-00013

Anema JR (2004) The effectiveness of ergonomic interventions on return-to-work after low back pain; a prospective two year cohort study in six countries on low back pain patients sicklisted for 3–4 months. Occup Environ Med 61:289–294. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2002.006460

Anema JR, Schellart AJM, Cassidy JD et al (2009) Can cross country differences in return-to-work after chronic occupational back pain be explained? an exploratory analysis on disability policies in a six country cohort study. J Occup Rehabil 19:419–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-009-9202-3

Gatchel RJ, Polatin PB, Mayer TG, Garcy PD (1994) Psychopathology and the rehabilitation of patients with chronic low back pain disability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 75:666–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-9993(94)90191-0

Gross DP, Battie MC, Cassidy JD (2004) The prognostic value of functional capacity evaluation in patients with chronic low back pain: part. 1: timely return to work. Spine 29:914–919. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-200404150-00019

Steenstra IA, Anema JR, Bongers PM et al (2006) The effectiveness of graded activity for low back pain in occupational healthcare. Occup Environ Med 63:718–725. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2005.021675

Persechino B, Fontana L, Buresti G et al (2016) Professional activity, information demands, training and updating needs of occupational medicine physicians in Italy:national survey. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 29:837–858. https://doi.org/10.13075/ijomeh.1896.00736

Sakowski P, Marcinkiewicz A (2018) Health promotion and prevention in occupational health systems in Europe. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 32(3):353–361. https://doi.org/10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01384

Persechino B, Fontana L, Buresti G et al (2017) Collaboration of occupational physicians with national health system and general practitioners in Italy. Ind Health 55:180–191. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2016-0101

Persechino B, Fontana L, Buresti G et al (2019) Improving the job-retention strategies in multiple sclerosis workers: the role of occupational physicians. Ind Health 57:52–69. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2017-0214

Iavicoli I, Gambelunghe A, Magrini A et al (2019) Diabetes and work: the need of a close collaboration between diabetologist and occupational physician. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 29:220–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2018.10.012

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Grants (BRIC–2021 ID4, BRIC–2022 ID28 and BRIC–2022 ID30) of the Italian Workers Compensation Authority (INAIL).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Informed consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Russo, F., Papalia, G.F., Diaz Balzani, L.A. et al. Prognostic factors for return to work in patients affected by chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Musculoskelet Surg (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12306-024-00828-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12306-024-00828-y