Abstract

Against the background of increasing challenges within the European Union related to ageing societies, a prevailing low interest environment, increasingly mobile life and work across the EU and the general distribution of wealth, several stakeholders within the EU have acknowledged the need to support the adequacy of national public pension schemes. This resulted in the conception of a Pan-European Personal Pension Product (PEPP), voluntary and portable across the European Economic Area (EEA), aiming at combining profitability, transparency as well as the security and quality of the related investments. Embedded into the greater scheme of the aspired European Capital Markets Union, PEPP is intended as simple and affordable savings option for everyone with the goal of closing the pension gap. This paper revisits the process towards the current, finalized state of PEPP, exploring its product features, regulatory requirements and key challenges with regard to the possible emergence of products since 2022.

Zusammenfassung

Vor dem Hintergrund wachsender Herausforderungen innerhalb der Europäischen Union (EU) bedingt durch alternde Gesellschaften, eine langanhaltende Niedrigzinsphase, gesteigerte Flexibilitätsanforderungen in der Lebens- und Karriereplanung sowie generellen Aspekten der Verteilung von (Spar‑)Vermögen, erkannten Stakeholder EU-weit die Notwendigkeit zur Stärkung öffentlicher Rentensysteme. Hieraus resultierte die Entwicklung eines Paneuropäischen Privaten Pensionsproduktes (PEPP) als ergänzende, freiwillige und innerhalb des Europäischen Wirtschaftsraumes (EWR) mitnahmefähige Option zur Altersvorsorge, darauf ausgerichtet, Profitabilität, Transparenz sowie Sicherheit des zugehörigen Anlageportfolios zu vereinen. Nebst dessen Einbettung in den Plan zur Schaffung einer europäischen Kapitalmarktunion folgt das Konzept dem Ziel einer verständlichen und erschwinglichen Produktalternative zur Schließung wachsender Rentenlücken. Die vorliegende Arbeit widmet sich dem Prozess von der Konzeption bis hin zum finalisierten Stand des PEPP mit einem Fokus auf dessen Hauptmerkmale, den umspannenden regulatorischen Rahmen sowie den zentralen Herausforderungen für die seit 2022 mögliche Einführung entsprechender Produkte.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The increasing challenges within the European Union (EU) related to demographic changes and low interest rates have led to a consensus among EU Member States that national public pension schemes are in need of support. The so-called “pension gap” refers to the difference between the pension income needed for an adequate standard of living during retirement and actual/expected statutory pension income.Footnote 1 As this gap can be significant, it illustrates insufficient and underfunded (individual) retirement planning. Thus, even despite strong first pillar (or occupational) pensions in some countries as, e.g., in Germany, third pillar personal pension products (PPPs) are and will continue to be increasingly important. However, approaches towards tax relief or other incentives that may stimulate the enrolment in these PPPs are different across Member States and a harmonization thereof seems improbable.Footnote 2

Therefore, in 2012, the European Commission launched a call for advice, asking the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) to investigate on the possibility of an EU single market for personal pensions, yet aside from national rules, i.e. as “2nd regime”.Footnote 3 Over the course of several years, the idea of a Pan-European Personal Pension Product (PEPP) was developed and refined, ultimately leading to the “PEPP regulation”Footnote 4 of 2019. This Regulation describes minimum product, investment, transparency and regulatory features in order to label (existing) PPPs as PEPP. The present paper revisits the process up to the current state of PEPP, exploring the product features, regulatory requirements and general criticism with regard to the possible emergence of products by 2022. Finally, a practitioner-oriented investigation of challenges and opportunities discusses the feasibility and appropriateness regarding costs, taxes and the conversion of existing products into PEPPs with an emphasis on the German (life) insurance market.

The approach is introduced with a recap of the milestones towards the current implementation of PEPP and the surrounding Regulations. Apart from the European Commission and EIOPA as main institutions, many stakeholders such as insurance companies, institutions for occupational pensions and actuaries as well as their associations have provided feedback on the different PEPP features over almost a decade (see, e.g., EIOPA 2020e). Moreover, PEPP is embedded into the greater scheme of the Capital Markets Union (CMU), i.e. an action plan that is intended to significantly enhance the attractiveness and resilience of the European capital market (see European Commission 2020). It is suggested that investments into PEPP products channel (short-term) cash and bank deposits into longer-term investments, thereby supporting the goals of the CMU.

Following up, the product features and the architecture of PEPP are explored with the so-called “Basic PEPP” at the core. The Basic PEPP is a default investment option with a yearly 1% cost and fee cap on the accumulated capital that every provider of PEPP products is obliged to offer. Simultaneously, it also has to meet all general prerequisites defined by the PEPP regulation, such as certain product attributes (e.g. long-term accumulation, limited withdrawal possibilities), necessary information documents (i.e. PEPP Key Information Document, PEPP Benefit Statement) as well as a provider switching service. In practice, the entirety of all requirements is sometimes referred to as “wrapper product” (see Hooghiemstra 2020). However, certain degrees of freedom for PEPP providers remain, e.g. as to how they provide security for their investments (capital guarantees versus other risk-mitigation techniques). An important part of this paper’s contribution consists of an overview summarizing the PEPP product architecture and additional features that separate a (current) PPP from a (future) PEPP.

There are remaining challenges that especially the cost cap and taxes impose on the introduction of PEPP (see, e.g., Dieleman 2020). To this regard, current data is very heterogeneous across the European Economic Area (EEA) in many aspects: the level of premiums earned, acquisition costs and expenses, life insurance penetration rates and restrictions on remuneration systems of life insurance products. Whilst this might initially result in certain challenges, first-movers who are successful in, e.g., setting up a cost-efficient administration and distribution infrastructure for their (Basic) PEPP, will benefit from opportunities on this newly created market. Thus, based on the above-mentioned overview, current German PPPs or components thereof are investigated on their potential suitability as PEPP, i.e. identifying necessary adaptations. Ultimately, this is intended to support practitioners in their decision whether and how a new, European-wide personal pension product could extend their current product portfolios.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Sect. 2 provides the most basic definitions and the terminology of PEPP while also highlighting the most important milestones of its development. Sect. 3 follows up with a discussion of central (and mandatory) product components that separate a PEPP from current products. Sect. 4 discusses challenges and opportunities concerning the cost cap, taxation and necessary steps towards a German PEPP. Sect. 5 summarizes the results.

2 Towards a pan-European Pension Product

While the first cornerstones towards a PEPP framework were laid in 2012, the process up to its final introduction by 2022 underwent several changes in order to satisfy the requirements of the involved stakeholders, e.g. Member States, national and European legislators as well as (national) supervisory authorities. Hence, before discussing the product features in more detail, this article introduces the basic framework first, explores its basic terminology and outlines the timeline in order to acknowledge for the multilayered process up to the framework in its current form.

2.1 Definitions and basic PEPP framework

PEPP is developed as a voluntary pension scheme and primarily aims at closing the pension gap throughout the Member States of the European Economic Area (EEA) as well as contributing to the idea of a CMU. Since demographic challenges of the past and upcoming years put statutory pensions under stress, i.e. resulting in diminishing pension benefit levels, the enrolment in additional PPPs becomes increasingly important. Thus, the PEPP regulation provides a legal framework for an additional product option made available to future retirees all across the EEA that can be offered by a broad range of providers. However, it only intends to complement the existing public and occupational pension schemes instead of replacing or overruling them. Hence, despite being labeled as “product”, it is more appropriate to understand PEPP as set of distinct qualifying features that (already existing) products will have to incorporate in order to be sold as PEPP. Thus, PEPP can rather be understood as a quality seal or a “wrapper product” (see Hooghiemstra 2020).

For the formal definition of PEPP and its main features, the first Regulation (EU) 2019/1238 and the additional Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473 are of relevance. The latter specifies on the built-in cost cap—a very central feature throughout the conception of PEPP—and risk-mitigation techniques for the safekeeping of assets. Article 2(2) of the Regulation (EU) 2019/1238 of June 20, 2019 formally defines it as:

[…] a long-term savings personal pension product, which is provided by a[n] eligible financial undertaking […] under a PEPP contract, and subscribed to by a PEPP saver, or by an independent PEPP savers association on behalf of its members, in view of retirement, and which has no or strictly limited possibility for early redemption and is registered in accordance with this Regulation.

The PEPP regulation further describes the basic layout and essential components of PEPP. Aside from the general aim of supporting the stability and sustainability of public (national) pension schemes, it provides the key definitions and lays down first regulatory constraints, which are further specified in the ensuing regulations.Footnote 5 Against this background, it needs to be emphasized that a PEPP is not necessarily designed to match or substitute traditional annuities, as it does not insure longevity risk by default, which will be discussed in more detail in the next section.Footnote 6 The regulation further expands the above definition of PEPP by “a set of key characteristics of the product […] that should be included”.Footnote 7 At this point, it is important to note that the legislative framework should not overrule nor interfere with national law, which is generally referred to as a complementary or 2nd regime, as mentioned in the introduction. A brief summary of the basic terminology is given in Table 1. For the remainder of the paper, additional terms will be elaborated as needed.

Aside from definitions, the regulation addresses the registration of a PEPP, i.e. potential products have to be registered in a central public register kept by EIOPA.Footnote 8 Rules on cross-border provision and portability as well as distribution and information requirements are also presented.Footnote 9 The latter addresses the important pre-contractual information, i.e. the PEPP Key Information Document (PEPP KID) with its contents, as well as information provided during the term of the contract, i.e. the PEPP Benefit Statement (PBS). This is followed by the ruleset for PEPP providers and the investment options provided to PEPP savers during the accumulation phase.Footnote 10 Most notably, Article 45 defines “The Basic PEPP”, the default investment option, with its cost cap of 1% as one of the most central features of the entire regulation. Thereafter, aspects of investor protection and the switching of PEPP providers are laid out along with the possible forms of payout (i.e. annuities, a lump sum, drawdown payments or any arbitrary combination) during the decumulation phase.Footnote 11 The regulation concludes with information on supervision, penalties and some final provisions.Footnote 12 To this regard, the respective competent authoritiesFootnote 13 are tasked with the supervision while EIOPA overtakes a monitoring function. The subsequent legislative requirements of 2021 further specify on these regulatory standards as well as the built-in cost limitations and safety measures of the product.Footnote 14 However, the most basic framework and all central features were completed by July 2019.

2.2 Timeline

From the emergence of first ideas regarding an EU market for personal pensions up to the current state of PEPP, almost a decade has passed. As the most important milestone, the European Parliament and the European Council adopted the PEPP regulation by July 2019. Following up, EIOPA published a draft of regulatory and implementing technical standards (RTS/ITS) in August 2020 in order to further elaborate on several aspects anchored within the first Regulation. This led towards additional RegulationsFootnote 15 by the European Commission over the course of 2021 as well as “Guidelines on PEPP supervisory reporting” by EIOPA.Footnote 16 First products are expected at the earliest as soon as these Regulations become entirely applicable, i.e. by March 2022. In order to arrive at its current state, the PEPP framework underwent several minor and major changes. Table 2 provides an overview of the most important milestones, also including the partaking stakeholders during the process as well as the relevant steps towards the current status quo.

Since the framework and additional Regulations and requirements reached their final state, the current aim among stakeholders and regulators is the preparation of the product implementation. EIOPA therefore launched a survey on the potential offering of a PEPP (open March–May 2021). However, the meanwhile fixed key features aim for a high-quality pension products across the EEA.

3 Product features

Since PEPP technically does not define a new or unique class of products, but represents a framework of minimum (quality) requirements, there are several components to investigate. From a practitioner’s perspective, especially the ruleset for the Basic PEPP comprises certain restrictions. Moreover, the layout and the content of any information provided to a PEPP customer through the PEPP KID or the PBS are at the core of the most recent regulations. Thus, after exploring the basic product architecture and mandatory components of any PEPP, critical regulatory requirements will be investigated.

3.1 Product architecture and mandatory components

“PEPP should not aim at replacing existing national pension systems […]”Footnote 17, i.e. preserve the exclusive national competence on pension systems. Thus, and in the context of the CMU initiativeFootnote 18, the PEPP regulation can be characterized as “product passport” or “wrapper product” in an attempt to harmonize requirements and regulation across the different product characteristics, e.g. providers, custodians and customers. Hooghiemstra (2020, p. 3) elaborates: “PEPPs […] cover (1) third-pillar retirement products that are ‘wrapped’ into […] eligible PPPs that share (2) common PEPP features and (3) comply with PEPP ‘product regulation’”. Against this background and among the generally rather complex product regulation between and across the Member States of the EEA, Table 3 shows selected mandatory components that any provided PEPP needs to incorporate.Footnote 19 On a further note, the coverage of biometric risks is only optional and may even differ between the “sub-accounts” that the PEPP regulation introduces.Footnote 20 These sub-accounts play a crucial for the general functioning of PEPP across the different Member States as they represent separate (savings) accounts that can be understood as national compartments within a PEPP contract. They have to be opened for each different Member State, thus allowing for a distinct treatment of savings with regard to taxes, incentives and other legal requirements.Footnote 21

Hence, an existing PPP could already qualify as PEPP or require some modifications. Hereafter, it has to be registered in the “central public register” kept by EIOPA (henceforth valid in all Member States), which entitles both, providers and distributors, to sell it.Footnote 22 This publicly available, electronic register identifies each single PEPP, its registration number, provider and competent authorities together with the date of its registration and a complete list of Member States where the PEPP is offered and for which the provider offers a sub-account.Footnote 23 The application for the registration is, however, limited to financial undertakings under EU law, possibly constraining the set of eligible products.Footnote 24 Technically, multiple (third-pillar) retirement products can be “wrapped” as PEPP, broadly separable into insurance and non-insurance PPPs. First, insurance PPPs might be appropriate, like specific personal pension plans or hybrid (unit-linked) products with accumulation elements dedicated to a pension purpose. Alternatively, non-insurance PPPs can be further developed, which could include Alternative Investment Funds or even savings products by credit institutions.Footnote 25 With regard to a practical implementation, EIOPA’s preliminary report of 2014 (see Table 2 for a chronological context) has already listed examples of PPPs in EU Member States where many products are already regulated under EU law (see EIOPA 2014, Annex I and IV). In their overview, they directly assign the according EU law (e.g. CRD, UCITS Directive, etc.) to the presented products, if applicable, and otherwise, they state if EU law serves as informal reference within national legislation.Footnote 26 In addition, the provided tables might also indicate which product can be eligible as a PEPP, where a regulation at EEA level is seemingly important (see Hooghiemstra 2020).

Once a PEPP is registered, the PEPP provider (or an eligible PEPP distributor) can now advise a (prospective) PEPP saver on the registered product(s), potentially closing a contract. After having closed the contract, the PEPP provider then opens a PEPP account in the name of the PEPP saver (or beneficiary), which can consist of different sub-accounts.Footnote 27 It is allowed to commit to partnerships between PEPP providers in order to offer these sub-accounts with regard to the required portability. All transactions, i.e. contributions (saver) and benefits (beneficiary), shall be entered into the corresponding sub-accounts. Note that a person can be saver and/or beneficiary in each sub-account, depending on the legal requirements for accumulation and decumulation phases in the respective Member State. Third parties, e.g. independent PEPP savers associations, are allowed to contribute payments on behalf of a PEPP saver or multiple members (satisfying the funding requirement, see Table 3). PEPP providers may further appoint so-called “depositaries” with the safekeeping of the accumulated assets and other oversight duties, e.g. the general conformity with applicable (national) law. Furthermore, information on the contract (specifically the PEPP KID and the PBS) needs to be available, at least electronically, and upon request on another durable medium (e.g. on paper).

These observations show that the components and features of a PEPP share several similarities with already existing PPPs, while being condensed within a dedicated PEPP framework.Footnote 28 Against this background, Table 4 provides a first summary of PEPP’s essential components and compares them to established (German) PPPs with regard to mechanics, relevant frameworks and involved parties. Thus, it allows a first (non-exhaustive) impression of distinctive features and—with the previously mentioned characteristic of PEPP as a wrapper product in mind—helps identifying necessary steps towards transforming existing products into a PEPP. At a glance, two observations are apparent. Foremost, the characteristics that are linked to the portability of the product (essentially the sub-accounts and the switching service) are unique traits to PEPP, hence either transforming a PPP into a PEPP or designing an entirely new product, will require new approaches by the respective providers. Secondly, the relatively strict framework regarding the provision of information documents (i.e. PEPP KID and PBS with their specific templates being provided) implies a new methodology towards the presentation of risk and rewards. As it deviates from existing frameworks (e.g. the PRIIP risk indicators), the risk assessment processes also need to be (re-)designed for PEPP.Footnote 29 The following sections will elaborate on these and several of the other listed components in more detail as well, with an emphasis on customer protection and the special requirements of the Basic PEPP.

3.2 The basic PEPP and customer protection

The PEPP regulation is conceived with the goal of high levels of security and transparency towards customers across the EEA, where the “prudent person principle”Footnote 30 is one of the main determining factors.Footnote 31 Those requirements towards a proper identification and management of (asset) risk are complemented by the mandatory provision of information documents to the PEPP customer. Aside from the PEPP KID that shall inform any potential saver beforehand and the PBS that provides information throughout the accumulation phase, the PEPP regulation also specifically defines a low risk and low cost PEPP version by the Basic PEPP.Footnote 32 Among a maximum of six possible investment options, the Basic PEPP has to be offered as default investment option and stands out by explicitly including a cost cap, i.e. “costs and fees […] shall not exceed 1% of the accumulated capital per year”.Footnote 33 The remaining requirements apply analogously.

However, the original PEPP regulation only lays down the foundation for these features and was followed by the Delegated RegulationFootnote 34 (EU) 2021/473, which specified on the term “costs and fees” and included templates for the information documents. Table 5 gives a an overview of the features and their main characteristics that are now explored in detail.

3.2.1 The cost cap

As default investment option, the Basic PEPP aims at “recoup[ing] the capital”.Footnote 35 Costs and fees are not allowed to “exceed 1% of the accumulated capital per year”Footnote 36, which includes administrative costs, investment costs and distribution costs that incur at the level of the provider or an outsourced activity. However, costs linked to a capital guarantee, which is due at the start or during the decumulation phase, shall not be included in the cap, but disclosed separately within PEPP KID and PBS.Footnote 37 This also holds true for all other costs of additional features not directly linked to the requirements of the PEPP regulation, e.g. switching services.

3.2.2 Risk-mitigation techniques

Risk-mitigation techniques (RMTs) represent a crucial component towards securing an adequate retirement income, hence EIOPA developed several general and special requirements anchored across the regulations. First, RMTs shall ensure an expected loss of less than 20% at the end of the accumulation phase, where the expected loss is defined as the shortfall between the sum of all contributions and the accumulated capital under stress (which equals the fifth percentile of the distribution).Footnote 38 Additionally, they should aim at outperforming the annual inflation rate with a probability of 80% over an accumulation phase of 40 years.Footnote 39 If a Basic PEPP is not offered together with a capital guarantee, the investment strategy has to ensure a recuperation of the capital with a probability of at least 92.5% at the start or during the decumulation phase (the challenges of these requirements are briefly discussed in Sect. 4.3).Footnote 40 If the RMT (including a life-cycle approach) is subject to adverse developments within three years towards the end of the accumulation phase, a PEPP provider can extend the last phase of the respective RMT-approach by an “appropriate additional time” of up to three years; however, this requires the saver’s explicit consent.Footnote 41 Generally, any RMT has to be designed in order to protect any (group of) PEPP saver(s) equally and any (performance-linked) remuneration of individuals involved with their implementation has to support the objectives of the RMT.Footnote 42 Furthermore, if a PEPP saver opts out of his or her current investment option or switches the provider, the corresponding reserves and returns have to be allocated to the leaving PEPP saver, where the allocation has to be equally fair towards leaving and remaining PEPP saver(s).Footnote 43

In the specific case of a life-cycle strategy, the provider defines average exposures (e.g. to equity, debt instruments, etc.) for sub-portfolios which correspond to the different phases of a life-cycle.Footnote 44 Furthermore, the strategy shall ensure higher investment returns (accepting higher risks) for savers furthest away from the decumulation phase while focusing on liquid, high-security investments with fixed returns for savers close to the end of the accumulation phase.Footnote 45 To this extent, if a building of reserves is required, the allocation rules have to be transparent and comprehensible.Footnote 46 During phases with positive (negative) investment returns, the building of (drawing from) reserves has to be (equally) fair for the individual (group of) PEPP saver(s). The corresponding assets invested on behalf of the saver also have to remain clearly identifiable.Footnote 47 If the accumulation is equipped with a minimum-return guarantee, its features, including an inflation-adjustment, have to be specified and addressed within the PEPP KID and PBS.Footnote 48

The abovementioned ruleset and the specifications outlined below for the information documents are derived from a stochastic model developed by EIOPA.Footnote 49 Within their analysis, they investigate 64 investment strategiesFootnote 50 regarding their risk-profile, the performance of the respective portfolios as well as the possibilities to build a “summary risk indicator”. This indicator for the investment options ranges from 1–4 and is allocated based on (1) the risk of not recouping inflation-adjusted contributions, (2) the expected shortfall and (3) a comparison of expected rewards towards reaching a certain level of PEPP benefits at the start or during the decumulation phase.Footnote 51 The results for the single indicators are aggregated to a summary risk indicator by choosing the higher of the two risk indicators (1 or 2) and comparing it to the indicator of the rewards category (3).Footnote 52 This information is essential for the PEPP KID, which is explored in the following.

3.2.3 The PEPP key information document

With the goal of optimal transparency and product comparability in mind while preserving high standardization, the PEPP KID as the first of the two important information documents aims at providing “easy to read and understand” information about PEPP, including a template.Footnote 53 It replaces and adapts the PRIIP information documentFootnote 54 and can be subdivided into three main sections: “What is this product?”, “What are the risks and what could I get in return?” and “What are the costs?”.Footnote 55 There are also the two closing sections “What are the specific requirements for the sub-account corresponding to the Member State?” and “How can I complain?”.Footnote 56 The first one briefly summarizes factors for investment returns and pension outcomes, information on the determining factors for returns, underlying assets, the scale of contributions and the period until retirement. Most importantly, the summary risk indicator has to be mentioned, however, it also includes the abovementioned RMTs, especially the assignment of returns to a specific contract. Moreover, a description of the intended target group of savers for the specific PEPP product (i.e. investment option) is mandatory. These savers have to be identified by the PEPP provider through their investment loss tolerance, investment horizon, experience with and knowledge of the financial markets as well as general needs and objectives.

Additionally, several features have to be addressed, i.e. the forms of out-payments, comprised PEPP retirement benefits (with further specifications in the second section of the PEPP KID), premiums and effects of covered biometric risks, if applicable, as well as information on the portability service (e.g. general information, available sub-accounts, provision of a switching service). Finally, it includes information about the switching of investment options (conditions and costs), the investment’s performance with regard to Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) factorsFootnote 57 and a reference to the past performance of the investment options, the latter made available electronically on the PEPP provider’s website. The section “What are the risks and what could I get in return?” contains a general risk-return profile explaining expected returns depending on the choice of strategy, including explanations about maximum losses and information on the stressed scenario on which the calculation of the expected loss is based. There is also a mandatory set of standardized scenarios (favorable, best estimate, unfavorable)Footnote 58 providing estimates of possible benefits. These account for different times to maturity (40, 30, 20 and 10 years) and are adjusted for effects of inflation, including a translation into today’s values of purchasing power. The section about costs is in line with the implementation of the cost cap, i.e. any costs at the level of the provider or an outsourced activity have to be denoted. Furthermore, initial costs (occurring before saving in the PEPP) are separately disclosed. All costs are identified in terms of monetary values and as percentage, including their compound effect based on a standardized monthly contribution. This also involves information on administrative costs (accounting, contributions, payments, etc.), costs of safekeeping, portfolio transaction costs, costs of providing advice and finally information on distribution costs (marketing, selling) or any charged (financial) guarantee.

3.2.4 The PEPP benefit statement

In line with the transparency and comparability requirements that led towards the design of the PEPP KID, the PBS is mandatory for each sub-account.Footnote 59 It consists of the sections “Product name”, “How much have I saved in my PEPP?”, “What will I receive when I retire?”, “How has my PEPP changed in the last 12 months?”, “Key factors affecting the performance of my PEPP” and “Important Information”. The first section briefly summarizes details of the PEPP saver, the earliest date of decumulation, identification of the PEPP provider and the contract as well as the Member State and its competent authorities. The second section lays down information of the total amount within the account, paid-in contributions and net returns (including information on biometric risk premiums, if applicable). Regarding the third section, national rules have to be included into the projections of pension benefits with respect to actual contributions, expected contribution levels and individual terms and conditions, leading up to a projection of accumulated capital and retirement benefits. Information on changes within the last 12 months (section four) and the data given within the previous sections should in fact “reconcile”Footnote 60 starting and end balances while providing information on costs and fees, guarantee mechanisms/RMTs and ESG factors. The final section comprises possible changes to the PEPP terms and conditions, sources for supplementary information and references to the ESG-related investment policies. Analogously to the PEPP KID, a template for the PBS is provided.Footnote 61

3.3 Further regulation

It is (mainly) left to the competent national authorities to ensure the compliance of PEPP providers and their offers with the PEPP regulation. EIOPA, aside from keeping the central public register, is tasked with the monitoring of the PEPP market and its products in general. However, in certain cases, product intervention or even the prohibition of service might be necessary. If meeting the necessary requirements, the competent authorities can impose said prohibition or restriction.Footnote 62 To this regard, EIOPA overtakes the role of facilitation and coordination of any taken action to ensure its appropriateness. However, if EIOPA decides on (different) measures, these will take “precedence over any previous action taken by a competent authority”.Footnote 63

3.3.1 Guidelines on PEPP supervisory reporting

The published “Guidelines on PEPP Supervisory Reporting” (see EIOPA 2021b) specify on the existing legislative frameworks by seven additional guidelines and are addressed to competent authorities and PEPP providers collectively. These guidelines become applicable by March 22, 2022. As Table 6 shows, two main types of reports are relevant: quantitative supervisory reporting and the “PEPP Supervisory Report”. The first reporting is based on reporting towards the national competent authorities. It is required annually and already anchored within the original PEPP regulation.Footnote 64 In order to enable a supervisory review process, it should comprise quantitative and qualitative data, historic, current or prospective elements and data from internal or external sources (or any combination) as necessary.Footnote 65 With the goal of a comprehensible and consistent reflection of the PEPP business in mind, PEPP providers are also tasked with the submission of a list of Member States for which they offer sub-accounts, a number of requested and actual openings of sub-accounts as well as requested and actual switches or transfers by PEPP savers. The second reporting, i.e. the PEPP Supervisory Report, is formally defined as the regular and ad hoc narrative report that enables PEPP providers to report on the development of the PEPP business and allows to monitor the effectiveness of RMTs and the continuous compliance with the PEPP regulation.Footnote 66 It is due every three years, with the exception of the year of the first registration that requires an immediate end-of year report and its content is further specified through Guidelines (3–7). The requirements for this submission aim for a holistic perspective on the PEPP provider’s business. Each of the areas (see Table 6) contains a more detailed list of aspects to cover. Aside from the rather quantitative description of the business (performance, contributions, etc.), several guidelines also contain qualitative assessments within their respective area, some of them explicitly declared as “high-level” descriptions or reviews of the administrative board.Footnote 67 For example, concerning the general PEPP business, a description of distribution channels, switching procedures and the nature and outcome of complaints is necessary.Footnote 68 This is complemented by an explanation of partnerships (e.g. for sub-accounts), their functioning and the affected PEPP contracts. Analogously, the guideline on risk management and RMTs incorporates a review of scope, frequency and requirements of the management information that is presented to the administrative board.

3.3.2 Product intervention powers and the convergence of supervisory reporting

Two additional regulations complement the previous guidelines. The first of the two regulationsFootnote 69 specifically addresses questions of EIOPA’s product intervention powers. To this regard, “significant investor protection concerns” and “threats to the orderly functioning” of financial markets are assessed separately. While “threats” impose a high level of danger to the markets, “significant concerns” should already suffice to require an intervention by EIOPA.Footnote 70 Thus, the regulation defines seven sets of criteriaFootnote 71 that need to be considered. These comprise the general complexityFootnote 72 of the PEPP product, the PEPP saver to whom it is sold, its degree of innovation (e.g. the RMTs), the leverage and the total amount of accumulated capital. Finally, the orderly functioning and integrity of the financial markets (e.g. financial practices) and the specific situation of the PEPP provider or distributor (e.g. solvency and business model) are mentioned explicitly. Hence, if significant concerns arise in any one of these criteria, EIOPA is allowed to take action. However, in accordance with the PEPP regulation, a prohibition or restriction may be subject to exceptions or certain circumstances and has to be reevaluated at least every three months. If not renewed, it automatically expires after this period.

The second regulation specifies on the reporting to national competent authorities.Footnote 73 It encourages the standardization of approaches in order to improve a comparability, efficiency and to avoid double reporting towards national authorities and, ultimately, EIOPA.Footnote 74 Basic information delivered by a PEPP provider should enclose their risk management system (including governance), specifically for risks deriving from PEPP products, as well as a description of the pursued business (in relation to the provider’s operating sector). The information also includes the type and management of (active/passive) investments, offered guarantees, the implemented RMTs, the size of assets and contributions and a list of home Member State and host Member State of the PEPP provider. Finally, relevant risks (e.g. liquidity, market, credit or reputational risks) as well as valuation principles for solvency purposes have to be considered.

4 Challenges and opportunities

The conception of PEPP directly involved many stakeholders, e.g. political representatives or financial undertakings that can be eligible providers under the PEPP regulation. Furthermore, several groups and organizations that are affected indirectly by the emergence of new products, their provision or their management (e.g. IORPs, actuaries and their associations or insurance brokers, etc.) have contributed over the course of the years. This led to a collection of feedback on specific characteristics of PEPP, primarily on the cost cap and the tax treatment (see, e.g. EIOPA 2020e), which will be explored in the following.

4.1 Costs

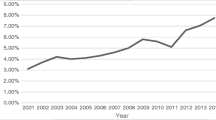

The general requirements across all regulations leave a relative freedom concerning the exact specification of a PEPP. For example, there are neither prescribed default payout options during the decumulation phase nor fixed (minimum) contract terms or contributions.Footnote 75 Those aspects need to be specified by the respective Member State’s sectorial law or by PEPP providers themselves. In contrast, the Basic PEPP as default investment option is explicitly equipped with the mandatory cost cap of 1% of the accumulated capital per year. The adequacy of this value has to be reviewed every two years by the European Commission after consulting EIOPA and the other European Supervisory Authorities.Footnote 76 Foremost, a uniform data basis on (average) costs of current PPP’s could help assessing the appropriateness. Additionally, despite pursuing a mostly uniform framework, the specifics of each Member State’s Regulations need to be considered at some point if the implementation of PEPP aims to be effective across the entire EEA. To this regard, EIOPA’s insurance statistics on premiums, claims and expenses (see EIOPA 2021c) may provide a first proxyFootnote 77 for observations as they extract data from Solvency II reporting templatesFootnote 78 and aggregate them by country as well as the EEA. Table 7 provides selective data concerning the life category for the EEA and GermanyFootnote 79 focusing on the total asset exposuresFootnote 80 as basis for our calculations to achieve the best possible comparability with regard to the cost cap.

Under the assumption that the reported cost categories and the total asset exposure can be translated into the PEPP terminology of “administrative, investment and distribution costs” and “accumulated capital” (see Table 3), Table 7 supports EIOPA’s viewpoint of a cost cap that is “challenging in initial phases of offering PEPPs […], [but] is not excessively low” (see EIOPA 2020e, p. 5). The data also suggests that future PEPP providers would profit from higher cost-efficiency of their product distribution channels, as acquisition expenses represent the largest portion—already reaching close to 1% on the level of individual PPPs on an aggregate basis. However, the overall share of acquisition expenses can severely differ across Member States and the provided dataset by EIOPA is not conclusive due to exceptions on the national level of reporting. Against this background, Table 8 relates the acquisition expenses for selected countries to the reported asset exposure. Moreover, some countries can be identified where national law restricts or prohibits remuneration systems, which might further influence the reported results.Footnote 81

The three largestFootnote 82 markets of France, Germany and Italy show relatively high ratios of acquisition expenses whereas Denmark and the Netherlands show very low ratios, possibly due to the elaborated restrictions in place. There are other countries with smaller market shares but their reporting of asset exposure is limited, i.e. the respective percentages are not included in Table 8.Footnote 83 To this regard and in the context of life insurance distribution in Europe, Klotzki et al. (2017) investigate several key drivers of distribution costs based on a dataset for the European insurance market. They also analyze the effects of commission bans in the case of Denmark and Finland, where they observe an increase in life penetration and life density for both countries in the years that follow the introduction of those bans.Footnote 84 In Sweden, the financial supervisory authority (Finansinspektionen) advocated for a ban on commissions in conjunction with advice in 2016, however, commission payments are (still) not fully restricted and the effects of the restrictions in place are continuously being monitored.Footnote 85 While the effects of the introduction of PEPP may differ across Member States, a uniform framework is likely to be beneficial, especially for countries where distribution costs may be higher. It either forces national providers to reduce their distribution costs accordingly or provides a facilitated access to foreign providers or distributors, thereby rendering the market more attractive for providers with well-established distribution channels. From the perspective of PEPP savers, both cases can be advantageous.

Some other questions remain. The opposing approaches of commission payments versus financial consulting on a fee basis is relevant for the comparability of Basic PEPPs in general. Table 8 shows significantly lower ratios of acquisition costs for countries with (stronger) regulations on commissions, i.e. Denmark and the Netherlands.Footnote 86 However, the data does not necessarily account for other costs related to consulting or advice. These might either not be within the scope of an insurer’s reporting or, regarding PEPP specifically, not be entirely identifiable or relatable to advice leading up to the closing of a (specific) contract. Overall, this can hinder the comparability of (Basic) PEPP products across the EEA. To account for the providers’ perspective, the consultations carried out by EIOPA that preceded their final advice on RTS (see EIOPA 2020e) contain further comments of stakeholders on how they perceive the intended “all-inclusive” approach of the cost cap. Therein, data from Italy, Australia and the UK is provided where equity-based products exist that fulfill the 1% cost cap, however excluding the cost of (general) advice. As these and further costs for the implementation and distribution of new products typically result in one-off (and up-front) costs, they characterize a threshold that may put first movers at a disadvantage. EIOPA acknowledges this critique, but refers to the initial period of a PEPP product (i.e. the period of five years up to the earliest possible switch of provider) as amortization period (see EIOPA 2020e) and the general long-term characteristic of the product.

On a more general note, markets in countries with a comparatively strong first pillar of retirement income could be disadvantageous towards the distribution of (new) third pillar products. Conceiving further products that are in line with the PEPP regulation will result in a competition with established products. Even despite the European Commission’s recommendation to grant the same (tax) treatment to PEPP as to other national PPPs, this narrows the market even further (see European Commission 2017a).

4.2 Taxes

Tax regulations for PEPP products will not be harmonized across the EEA, as tax regimes remain under national competence. Therefore, the PEPP regulation is deliberately designed in a way to not interfere with them.Footnote 87 However, the taxation of occupational or third-pillar pension products is handled differently in each Member State while many countries incentivize private contributions to (voluntary) additions to public pension schemes. This serves as pressure relief for statutory pensions but obstructs the mobility of retirement income. Difficulties might therefore occur during the accumulation or decumulation phase of a PEPP product, or upon a switch of Member State or provider, respectively.

4.2.1 Accumulation phase

Generally, closing a contract that fulfills all conditions of a favorable tax treatment under national law requires equal treatment independent of whether the provider (insurer) is established in the home or another Member State. Therefore, a properlyFootnote 88 designed PEPP merits equal treatment/tax incentives to corresponding local insurance products (see Dieleman 2020). More specifically, any contributions during the accumulation phase will be handled through the mechanics of sub-accounts. As PEPP Providers need to open them for their PEPP savers, they essentially have to assure that any requirements for possible tax reliefs are met for the respective sub-account. These might differ for every Member State, i.e. payments (and sub-accounts) can vary when moving within the EEA whilst the PEPP product remains the same.Footnote 89

4.2.2 Decumulation phase

The taxation of retirement benefits also imposes difficulties towards a fair treatment across Member States. Assuming a resident who remains within the EEA throughout his or her retirement, it is still questionable which Member State is entitled to tax the retirement benefits if the Member State where he or she contributed and the Member State where benefits are finally received are different. In a worst-case scenario, the “contribution Member State” might not (or just weakly) incentivize payments whereas the “benefit Member State” does not provide a tax relief for retirement benefits. This worst case will eventually require a mandatory exemption of benefit payments.Footnote 90

As for the other cases, most of them are covered either by bilateral tax treaties between Member States or resort to national legislation to avoid the so-called double taxation. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) provides a “OECD Model Tax Convention” as basis for tax treaties that generally cedes tax treatment to the state of residence of the saver/beneficiary, independent of the form of out-payment (see OECD 2017). However, Dieleman (2020) identifies four common deviations. The first one asserts an equal treatment of occupational and personal pensions, which is sometimes extended to lump sum and annuity payments. The second deviation extends the first one by the fact that lump sum payments may be taxed in the Member State of the provider if that state already granted tax relief on contributions. The third deviation further includes the possibility to tax annuity payments in the Member State of the provider under certain conditions. Finally, the fourth deviation is a modification of the third where the taxation of the annuity is limited to a percentage (e.g. 15% or 20%) of the annuity.

Throughout both phases, instead or on top of the change of the state of residence, a PEPP saver is contractually allowed to switch the provider (switching service). Within a Member State, the risk of tax issues should be minimal when opting for a new provider, while this might be more difficult for providers outside the savers’ current Member State, since a Member State could intend to reclaim its granted tax incentives (see Dieleman 2020). However, due to the different sub-accounts for different Member States, any PEPP saver is able to continue his or her contributions after changing his residence, which renders this risk minimal.

Upon the emergence of the first products, further questions that require specialist knowledge beyond the currently existing case law or individual cases will arise, giving room for research and creative solutions regarding European-wide retirement saving plans.

4.3 From German PPPs to a German PEPP

On a concluding note and with regard to upcoming products by 2022, it is questionable whether existing products might be valid considerations to be “wrapped” as a PEPP. Table 4 already points out discrepancies between current (traditional) products that are used for financing retirement income. Recall that any biometric insurance component is only optional within the PEPP framework, whereby, at first glance, the general scope of eligible products would be further increased.

Focused on a German perspective however, three issues can be identified. First and foremost, costs will be a prime issue before introducing any PEPP. Even despite a well-established market for life insurance products together with distribution channels, the data above shows that especially the acquisition expenses are high (in comparison and on an aggregate basis). Moreover, a comparatively strong first pillar of statutory pension income can still dampen the demand for third-pillar products, which can be different outside of Germany.Footnote 91 Nevertheless, first movers that are successful in providing a PEPP at reduced (distribution) costs might use this as sales argument, assuming that the other product characteristics are able to compete with established alternatives. To this regard, online distribution channels and a higher standardization seem beneficial, which also represents a driver throughout the regulations.Footnote 92 Second, the necessary infrastructure needs to be provided not only for the distribution of PEPP but also within the undertakings that want to provide it. For example, aside from requirements by the IDD or the POG (as mentioned in Table 4) that will result in (recurring) expenses, national law requires separate guarantee assets for PEPP contracts during the accumulation phase, possibly further increasing (up-front) administration costs.Footnote 93

As final and important aspect, Graf and Kling (2022) have shown that, especially in the current market environment, the above-mentioned requirements for the RMTs with the goal of limiting losses while outperforming inflation are not fulfilled by any available product/investment strategies that are common on the market.Footnote 94 In particular, none of the discussed approaches meets all requirements (simultaneously). More so, referring to the summary risk indicator that is mandatory within the PEPP KID, risk indicators are high while return indicators are low. This holds true even when completely disregarding fees. Only an increase of the overall market interest rate while also raising the risk premium for equities would fulfil the RMT requirements. Thus, a transparent comparison of current products (transformed into possible future PEPPs) will require further calibration or an adaption of the ruleset.Footnote 95

5 Conclusion

Financing retirement income (and consumption) becomes increasingly challenging against the background of current demographic changes. Statutory and occupational pension systems that need to face these challenges render third-pillar pension products more important, as they provide the much-needed additional variety and support of post-retirement income. The present paper revisits the undertaken steps towards the (current) final state of PEPP, its central components and necessary steps towards the introduction of products, as first examples thereof can be expected during 2022. The PEPP regulation is designed as framework for a private pension product, created to enable an equal level playing field across all Member States and embedded into the greater scheme of an EU capital markets union. With the aim of closing the pension gap, while also ensuring the security, transparency and portability of their savings for prospective retirees all across Europe, PEPP has become a challenging task with many aspects to consider.

Initiating the present review with a recap of the milestones towards the finalized state of PEPP allowed to identify the different stakeholders, e.g. the European Commission, EIOPA, insurance companies and actuaries. The CMU, a further ambitious goal, has also influenced its development, intending to channel cash and bank deposits into longer-term investments, increasing the overall available capital for investments. The ensuing systematization of the (Basic) PEPP product features, e.g. the cost cap, information documents and other important prerequisites, contributes to a practitioner-oriented perspective for possible future PEPP providers. With biometric insurance components only being optional, the pool of possible products remains potentially large. To this regard, the overview also extracts other necessary and mandatory components and identifies their interdependencies. However, referring to the idea of PEPP as quality seal or set of minimum requirements, certain degrees of freedom for product design remain. Thus, a further contribution consists in the identification of features that separate a (current) PPP from a (future) PEPP.

The final outlook on challenges and opportunities concludes the present review with an emphasis on the cost cap feature of the Basic PEPP—both, a challenging aspect for providers in the early phases of the product as well as a selling point in the future. The heterogeneity regarding the (life) insurance penetration and the diversity of retirement products paired with the differing vigorousness of public pension systems across Member States in Europe will however pose various challenges in the future. To this extent, arguments (with a focus on costs) that emerged during the conception of PEPP are reviewed and compared to current market and insurance data. Ultimately, this allows identifying the main hurdles regarding the steps from existing PPPs towards the introduction of a PEPP.

Overall, it can be concluded that PEPP shows a promising approach, facing challenges of costs, tax-treatment and (region-specific) market constraints. The European Commission and EIOPA designed a realistic, but very challenging framework that will require actions by all future providers: working more cost-efficiently, enhancing cooperation across Europe among insurers to ensure product and capital mobility as well as finding new ways of efficient and transparent product distribution. Even if the current market environment does not (yet) favor PEPP products, the emerging considerations represent necessary steps towards the securing of sufficient retirement saving in the future and the prevention of an aggravating pension gap.

Notes

See EIOPA (2014, p. 4) for this description within the present context. They provide data on “replacement rates” (relating median gross pensions to median gross earnings) for EU and other selected countries, where the gap is defined as difference between the individual replacement rate and the EU average. For Germany, the German Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (GFMLSA) provides detailed average and forecasted replacement rates within their report on the public pension system, i.e. 49.4% in 2020 with an expected decline to 45.8% in 2035 (see GFMLSA 2021, p. 39).

Article 113 of the Consolidated Version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) states that a harmonization of legislation concerning, e.g. taxes, has to be adopted unanimously, rendering uniform solution across all Member States rather unlikely (see TFEU 2012).

More precisely, the 2nd regime is a EU legal framework outside the laws of its Member States. It does not replace national rules and does not require transposition. Hence, the 2nd regime provides an alternative to existing Member States’ legislation in a particular field (see EIOPA 2013).

The term “PEPP regulation” in the literature commonly refers to Regulation (EU) 2019/1238 of July 2019.

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art 49.

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238 Recital (23).

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art. 5–13.

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art. 14–21 and Art. 22–40, respectively.

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art. 41–47.

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art. 48–51, Art. 52–56 and Art. 57–60, respectively.

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art. 61–74.

According to Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, competent authorities means the national authorities designated by a Member State to supervise PEPP providers and/or PEPP distributors, i.e. BaFin for the case of Germany.

See EIOPA (2021b).

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Recital (10).

The CMU action plan was launched in 2015 and reworked in 2020 and contains legislative and non-legislative actions with the objectives of a resilient economy recovery, granting access to financing for European companies, creating a safe environment for long-term investments and integrating national capital markets into a single (European) market.

The PEPP regulation interacts with other established (regulatory) frameworks, such as the Alternative Investment Fund Manager Directive (AIFMD), the Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities (UCITS) Directive, Market in Financial Instruments Directive 2 (MiFID II), Institutions for Occupational Retirement Provision (IORP) Directive II, Capital Requirements Directive (CRD V) and Solvency II (see Hooghiemstra 2020, p. 11). As an extensive study of legislative interdependencies is beyond the scope of this paper, a more detailed discussion can be found, e.g., in Hooghiemstra (2020) and the references therein.

If biometric risk coverage is offered by eligible non-insurance undertakings, a cooperation with an insurance undertaking that is fully liable is required (under the respective sectorial law), see Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art 49.

See Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art 2 (23). Challenges regarding, e.g., the individual tax treatment are further discussed within Sect. 4.2.

An application for the registration of a PEPP has to be submitted to the competent authority, which, given complete and compliant with the PEPP regulation, requires a decision within three months. EIOPA registers the PEPP within five working days following the communication of the decision, see Regulation (EU) 2019/1238 Art. 5 and Art. 13, respectively.

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238 Art. 13.

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238 Art. 6.

There are several other possibilities, e.g. products of IORPs under certain restrictions and the respective national law or certain UCITSs, i.e. funds.

For example, according to the provided table, the UCITS Directive serves as legal framework for “investment fund savings plans” in Germany whereas there is no applicable EU law for “personal pension funds” in Spain but national legislation refers to the IORP Directive.

Recital (35) of the PEPP regulation states the obligation of a minimum requirement of at least two provided sub-accounts within three years of the application of the PEPP regulation by a provider.

Note that the framework’s requirements can be challenging, especially with regard to risk-return-profiles. Graf and Kling (2022) show that certain requirements can only be met under very specific market assumptions, which will be briefly elaborated within Sect. 4.3.

Directive 2009/138/EC, Art. 132 (2–4) specify on the “prudent person principle” for insurance and reinsurance companies as ruleset to ensure proper identification, measurement, control and report of asset risks as well as investment decisions in the best interest of policyholders and beneficiaries.

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Recitals (38), (46) and (47).

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art. 45.

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art. 45 (2).

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art. 45 (1).

Note that the translations of the PEPP regulation might contain inconsistencies, e.g. the German version suggests a 1% cap on the yearly-accumulated capital, which significantly differs from the English version, see Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art. 45 (2).

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473, Art. 13.

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473, Art. 14 (2a).

Note that the wording of the article suggests the limit for the expected loss as mandatory constraint, which does not hold true for the outperformance of inflation. Stochastic modeling, however, has to generally be taken into consideration. The general framework of stochastic models and the underlying assumptions are presented in EIOPA (2020d).

This requirement relaxes to 80% if the accumulation phase is less or equal to 10 years.

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473, Art. 14 (8).

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473, Art. 14 (5).

According to Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art. 44, a PEPP saver can switch investment options (at least) five years after closing the contract (or after a previous switch), which has to be free of charge.

Investments by PEPP providers shall generally follow the “prudent person principle” and further specified rules in Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art. 41., or more stringent national law, where applicable.

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473, Art. 15.

Within the first ten years of the establishing of a new PEPP, providing the reserve may require a loan or equity contribution by the PEPP provider. In this case, the provider has to inform the saver about profit-sharing mechanisms as well as the planned dis-investment over a maximum period of 10 years (see Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473, Art. 16 (4)).

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473, Art. 16 (1–2).

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473, Art. 17.

See EIOPA (2020d, pp. 2–4), where the stochastic model consists of multiple sub-models, calibrated separately: nominal interest rate model (two-factor Hull-White model, allowing for negative interest rates), credit spread model (Cox-Ingersoll-Ross model), inflation rate model (one-factor Vasicek model), equity model (geometric Brownian motion) and a separate index-based wage model based on average unemployment rates for different cohorts.

This comprises 25 life-cycle strategies, 13 strategies that build reserves from contributions and/or investment returns, 6 strategies that incorporate guarantees, 11 fixed portfolio strategies and 9 buy-and-hold strategies (see EIOPA 2020d, p. 53 f).

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473, Annex III, 1–7, with specifications for each single indicator.

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473, Art. 4 (1) and Annex III, 8.

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473, Recital (5) and Annex I.II for specific templates.

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Recital (38).

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473, Art. 3–5.

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473, Annex I.

ESG factors are underlined throughout all PEPP regulations, see, e.g. Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Recitals (8), (36), (43), (50) and Articles 25 and 28, however, a mandatory integration besides a general information policy is amiss.

The favorable scenario corresponds to the 85th percentile, best estimate to the median and the unfavorable scenario to the 15th percentile (Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473, Art. 10 & Annex III).

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473, Art. 10 (1).

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473, Art. 10 (1.f).

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473, Annex II.II.

Any measure of prohibition/restriction needs to satisfy four conditions: (1) reasonable saver’s protection concerns or a risk to the integrity of financial markets; (2) proportionality towards the nature of the risk and concerned PEPP savers; (3) proper consultation of other affected competent authorities; (4) no discriminatory effect on services of other Member States. Additionally, at least one month before taking effect, all involved competent authorities as well as EIOPA have to be notified about (1) the concerned PEPP, (2) the nature of the prohibition or restriction and (3) the corresponding evidence. Exceptions for urgent measures apply (see Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art. 63).

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art. 65 (8).

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art. 40 (5), where the requirements are always in addition to the respective sectorial law.

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art. 40 (3).

See EIOPA (2021b).

See, e.g., EIOPA (2021b), Guideline 4.1 (f), 4.2 (e) or 6.2 (e).

See EIOPA (2021b), Guideline 4.1 (g)–(f) and Guideline 4.2 (e).

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/895, Recitals (1) and (3).

For a detailed list of all criteria, see Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/895, Art. 1–7.

According to Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/895 Art. 1 (a)–(n), degrees of complexity are influenced by a multitude of factors and criteria, e.g. its long-term retirement nature, degrees of transparency of underlying assets, costs/charges and risk, techniques that draw the PEPP savers’ attention to non-essential features, potentially misleading product features, bundling with other products/services, etc.

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/896, Recitals (1) and (2).

Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Art. 45 (4).

The data may not include submissions of all eligible PEPP providers (or include submissions of non-eligible providers). However, it allows for a mostly standardized and comparable data basis on the level of EIOPA/EEA.

The statistics on premiums, claims and expenses contain life and non-life data based on the Solvency II reporting template S.05.01 of the Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2015/2450, and reporting template S.06.02 for asset exposures, respectively. For legal definitions and description of terms and categories, see the definitions within the regulation, specifically Annex II and III.

Note that EIOPA explicitly discloses that all data is forwarded from national competent authorities and is not subject to any further adjustment or review. Regarding the submissions for claims and expenses (asset exposure) in 2020, out of 333 (257) total reporting undertakings for Germany, 82 (68) were life, 223 (168) were non-life and the remainder were other/reinsurance. For the above calculations, only data for life undertakings are considered. Aggregated numbers on the EEA level: 2672 (1782) in total, 503 (387) life, 1467 (997) non-life and 702 (398) other/reinsurance.

Values and the number of submissions might not fully align within both categories due to national exemptions in reporting (see EIOPA 2021a, p. 7). As fewer undertakings report their asset exposure in detail compared to the expenses reporting, Table 7 slightly (and prudentially) overestimates the ratios.

France, Germany and Italy account for 49.32% of the total reported written premiums (net without reinsurance), while UK would add another 25.14% (see EIOPA 2021c).

Especially for countries with a small number of reporting entities, e.g. Bulgaria (2), Czech Republic (1) or Slovakia (1), the total asset exposure is not provided. When measuring acquisition expenses as share of the reported net written premiums instead of asset exposure, i.e. as alternative proxy, they present the highest ratios (up to 20%) among all reporting countries. For comparison, the countries comprised within Table 8 lie (well) below 8%.

See Klotzki et al. (2017, p. 312–313) where they provide a comparative analysis of different key figures from 2006 and 2013.

These are included in the reporting templates by definition (see Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2015, R2210).

Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Recital (23).

In this context, Commission Recommendation C (2017) 4393 of 29 June 2017 also refers to the TFEU, in particular, Articles 21, 45, 49, 56 and 63.

Annual contributions might be subject to a minimum amount, a yearly cap or even further limitation such as restricted or reduced lump sum payments. Exemplary figures, e.g. for the Netherlands, are provided in Dieleman (2020).

Based on existing case law (European Court of Justice, Case C-136/00 of 3 Oct. 2002), pension contributions towards EU-foreign insurance institutions have to be (fully) deductible if there is no other corresponding compensation for resulting retirement benefits.

Average replacement rates range around 45–50% in Germany, see GFMLSA (2021).

See, e.g., Delegated Regulation (EU) 2019/1238, Recitals (9) and (21).

Restrictions apply in some cases, for further details see “Schwarmfinanzierungs-Begleitgesetz”, BGBl. I, Nr. 30 of 10 June 2021.

These strategies include hybrid, (mixed) unit-linked as well as life-cycle strategies (see Graf and Kling 2022, p. 5 f.).

See Graf and Kling (2022, p. 8).

References

Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/473 of 18 December 2020 Supplementing Regulation (EU) 2019/1238 of the European Parliament and of the Council with Regard to Regulatory Technical Standards Specifying the Requirements on Information Documents, on the Costs and Fees Included in the Cost Cap and on Risk-mitigation Techniques for the Pan-European Personal Pension Product Regulation (EU) 2019/1238 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on a Pan-European Personal Pension Product (PEPP) (2021). Official Journal of the European Union, L 99/1. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2021/473/oj. Accessed 25 Aug 2022

Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/895 of 24 February 2021 Supplementing Regulation (EU) 2019/1238 of the European Parliament and of the Council with Regard to Product Intervention (2021). Official Journal of the European Union, L 197/1. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2021/895/oj. Accessed 25 Aug 2022

Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2021/896 of 24 February 2021 Supplementing Regulation (EU) 2019/1238 of the European Parliament and of the Council with Regard to Additional Information for the Purposes of the Convergence of Supervisory Reporting (2021). Official Journal of the European Union, L 197/5. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2021/896/oj. Accessed 25 Aug 2022

Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2015/2450 of 2 December 2015 Laying Down Implementing Technical Standards with Regard to the Templates for the Submission of Information to the Supervisory Authorities According to Directive 2009/138/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (2015). Official Journal of the European Union, L 347/1. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg_impl/2015/2450/oj. Accessed 25 Aug 2022

Consolidated Version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) (2012). Official Journal of the European Union, C 326/47. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/treaty/tfeu_2012/oj. Accessed 25 Aug 2022

Dieleman, B.: Tax treatment of the PEPP: the new pan-European Personal Pension Product. Ec Tax Rev. 29(3), 111–116 (2020). https://doi.org/10.54648/ecta2020037

Directive (EU) 2016/97 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 January 2016 on Insurance Distribution (Recast) (2016). Official Journal of the European Union, L 26/19. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2016/97/oj. Accessed 25 Aug 2022

Directive 2009/138/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2009 on the Taking-up and Pursuit of the Business of Insurance and Reinsurance (Solvency II) (2009). Official Journal of the European Union, L 335/1. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2009/138/oj. Accessed 25 Aug 2022

European Commission: Technical advice to develop an EU single market for personal pension schemes (2012). https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/call-for-advice-on-ppps-072012_en.pdf, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Commission: Call for advice from ΕΙΟΡΑ to develop an EU single market for personal pension products (PPP) (2014). https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/call-for-advice-on-ppps-23072014_en.pdf, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Commission: Action plan on building a capital markets union (2015). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52015DC0468, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Commission: Capital markets union—accelerating reform (2016a). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52016DC0601, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Commission: Capital markets union: action on a potential EU personal pension framework (2016b). https://ec.europa.eu/finance/consultations/2016/personal-pension-framework/docs/consultation-document_en.pdf, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Commission: Commission recommendation (of 29.6.2017) on the tax treatment of personal pension products, including the pan-European Personal Pension Product (2017a). http://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/170629-personal-pensions-recommendation_en.pdf, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Commission: Proposal for a regulation of the European parliament and of the council on a pan-European Personal Pension Product (PEPP) (2017b). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Commission: Study on the feasibility of a European personal pension framework (2017c). https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/2f4dba21-a330-11e7-8e7b-01aa75ed71a1, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Commission: Capital markets union: commission welcomes political agreement on new rules to help consumers save for retirement (2019). https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_19_1108, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Commission: A capital markets union for people and businesses—new action plan (2020). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:590:FIN, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA): Discussion paper on a possible EU-single market for personal pension products (2013). https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/consultations/20130516_eiopa_discussion_paper_personal_pensions_def.pdf, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA): Towards an EU-single market for personal pensions—an EIOPA preliminary report (2014). https://register.eiopa.europa.eu/Publications/Reports/EIOPA-BoS-14-029_Towards_an_EU_single_market_for_Personal_Pensions-_An_EIOPA_Preliminary_Report_to_COM.pdf, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA): Consultation paper on EIOPA’s advice on the development of an EU single market for personal pension products (PPP) (2016a). https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/consultations/cp-16-001_eiopa_personal_pensions_0.pdf, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA): EIOPA’s advice on the development of an EU single market for personal pensions (2016b). https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/submissions/eiopa-16-494_letter_to_com_on_final_advice_ppp.pdf, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA): EIOPA’s advice on the development of an EU single market for personal pensions (2016c). https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/submissions/eiopas_advice_on_the_development_of_an_eu_single_market_for_personal_pension_products.pdf, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA): Call for expression of interest: expert panel on PEPP (2019a). https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/2019-02-05callexpertspeppregulation.pdf, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA): Consultation paper on the proposed approaches and considerations for EIOPA’s technical advice, implementing and regulatory technical standards under regulation (EU) 2019/1238 on a pan-European Personal Pension Product (PEPP) (2019b). https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/consultations/consultation_paper_on_pepp.pdf, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA): Consultation paper on implementing technical standards regarding the format of supervisory reporting and the cooperation and exchange of information between competent authorities for the pan-European Personal Pension Product (PEPP) (2020a). https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/consultations/cp-on-pepp-its-supervisory-reporting-cooperation.pdf, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA): Draft delegated regulation (EU) supplementing regulation (EU) 2019/1238 with regard to regulatory technical standards (2020b). https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/eiopa-20-500_pepp_draft_rtss.pdf, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA): Draft implementing regulation (EU) laying down implementing technical standards for the application of regulation (EU) 2019/1238 with regard to supervisory reporting and cooperation and exchange of information (2020c). https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/eiopa-20-501_pepp_draft_its.pdf, Accessed 7 Mar 2022

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA): Pan-European Personal Pension Product (PEPP): EIOPA’s Stochastic model for a holistic assessment of the risk profile and potential performance (2020d). https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/publications/eiopa-20-505_pepp_stochastic_model.pdf, Accessed 7 Mar 2022