Abstract

Many studies rest on the assumption that Uppsala Conflict Data Program data allow for an unbiased approximation to the temporal and spatial variation of deadly violence across cases. This research note compares fatality data in the program’s Georeferenced Event Dataset with the name-by-name compilation of victims in the Kosovo Memory Book for the period 1 January 1998–30 June 1999. The extent of underreporting of fatalities in the Georeferenced Event Dataset increases with conflict intensity. Events outside Kosovo and events with many fatalities are disproportionally covered. The Georeferenced Event Dataset is more likely to ignore an event when many other events occur on the same day. Surprisingly, international observer missions do not make an event more likely to be reported. Despite the mentioned problems, the dataset’s high estimates of conflict deaths mirror the temporal and spatial variation of violence fairly well. Some of the inconsistencies and biases identified in the selected case plausibly also occur in other conflicts. Events that span several months or lack specific location data impede analysis and are more prominent in the dataset’s entries for Kosovo than in the entire Georeferenced Event Dataset.

Zusammenfassung

Wie viele Studien annehmen, können die Daten des Uppsala Conflict Data Program das zeitliche und räumliche Variieren tödlicher Gewalt über verschiedene Fälle hinweg ohne größere Verzerrungen abbilden. Dieser Beitrag vergleicht die Angaben zur Zahl der Getöteten im Georeferenced Event Dataset mit der namentlichen Aufstellung der Todesopfer im Kosovo Memory Book für den Zeitraum vom 1. Januar 1998 bis zum 30. Juni 1999. Mit zunehmender Intensität des Konflikts sinkt im Georeferenced Event Dataset die Erfassung von Todesfällen. Ereignisse außerhalb Kosovos und Ereignisse mit vielen Todesopfern werden hingegen überproportional berücksichtigt. Das Georeferenced Event Dataset blendet tendenziell ein Ereignis aus, wenn am gleichen Tag viele andere Ereignisse zu verzeichnen waren. Überraschenderweise machen internationale Beobachtungsmissionen die Aufnahme eines Ereignisses nicht wahrscheinlicher. Trotz der erwähnten Probleme spiegelt der Datensatz mit seinen hohen Schätzungen der Todeszahlen die Unterschiede in der zeitlichen und räumlichen Verteilung der Gewalt recht gut wider. Einige der im ausgewählten Fall identifizierten Inkonsistenzen und biases gibt es vermutlich auch in anderen Konflikten. Ereignisse, die sich über mehrere Monate erstrecken oder zu denen genauere Ortsangaben fehlen, erschweren die Analyse. Sie machen in den Einträgen zum Kosovo-Konflikt einen größeren Anteil aus als im gesamten Georeferenced Event Dataset.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

According to the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), between 2015 and 2022, nearly one million people lost their lives due to battles and deliberate attacks on civilians in the context of armed conflicts.Footnote 1 Much empirical research is devoted to how to prevent, mitigate, or stop such violence. These studies need reliable data that are often difficult to collect. The UCDP has rendered outstanding service to research by compiling widely used datasets on organized violence. This research note deals with the UCDP’s Georeferenced Event Dataset (Sundberg and Melander 2013) that has provided the starting point for many analyses of the variation of conflict intensity across space and time. A large number of studies rely on this dataset to examine, for instance, the effects of military interventions (Fjelde et al. 2019), mediation (Ruhe 2020), and sanctions (Hultman and Peksen 2017). The Violence Early Warning System (ViEWS)Footnote 2 applies the Georeferenced Event Dataset (GED) to predict escalation. These and other studies rest on the assumption that the GED represents the spatial and temporal variation of organized deadly violence in a way that allows valid empirical findings to be made. Is this assumption correct?

Often, the best estimate of the total number of fatalities in the case literature is a multiple of UCDP’s best estimate but for the purpose of analyzing conflict dynamics underreporting is acceptable as long it is sufficiently consistent (cf. Krause 2017, p. 101). Findings can be valid despite underreporting, if measurement errors cancel each other out and there are no systematic biases. In order to identify potential biases in the GED, Otto (2013) and Weidmann (2015) draw on data on Afghanistan, while Dawkins (2020) addresses South Sudan. This research note continues the efforts to assess the Uppsala data and uses the conflict over Kosovo to identify potential inconsistencies and biases in the GED reporting. Unlike mere inconsistencies, biases refer to reporting errors that are pushed in a certain direction by a particular variable. A widely recognized name-by-name documentation of fatalities, the Kosovo Memory Book, serves as a yardstick for evaluating the GED. The Kosovo Memory Book is seen as “a remarkable example of a virtually complete list of every person killed in a modern war” (Jewell et al. 2018, p. 391). The conflict over Kosovo had more international peacemaking efforts devoted to it than many other conflicts. The media coverage was also more intense than elsewhere (Hawkins 2002, pp. 225, 235). It can thus be expected that in Kosovo at least some problems in reporting fatalities are less pronounced than in other conflicts.

This research note addresses the question of how well the GED covers the spatial and temporal variation of deadly violence in armed conflicts. It proceeds by summarizing previous studies and discussing potential inconsistencies and biases in media reporting on violent conflicts and thus in the GED. It then presents the Kosovo Memory Book. Using this compilation as a yardstick, the main part examines how well the GED mirrors the temporal and spatial variation of deadly violence in Kosovo. It considers the number of fatalities on a monthly basis, the different extent of violence across the municipalities in Kosovo, the number of deaths in an event, the number of events on the same day, and what impact the presence of international observers has on the GED’s coverage of deadly events. The concluding section discusses what insights gained from Kosovo mean for other conflicts and presents recommendations to the users and makers of the GED.

2 Fatality reporting by media and the UCDP

The GED covers deadly organized violence from around the world and seeks “to answer the call for geographically and temporally disaggregated data” (Högbladh 2022, p. 3). For this purpose, it identifies and documents events in the context of conflicts. An event is defined as “[a]n incident where armed force was used by an organised actor against another organized actor, or against civilians, resulting in at least 1 direct death at a specific location and a specific date” (Högbladh 2022, p. 4). The GED only considers direct deaths related to combat or attacks on civilians. Indirect deaths due to conflict, such as those caused by impeded access to food, water, shelter or health care, are excluded. Each entry contains information on the sources used for coding, the conflict and its parties, and the location and date of the deadly event (Högbladh 2022, pp. 5–11). UCDP “tends to be highly conservative when counting fatalities” and presents three estimates: The low estimate is the most conservative one, the high estimate reports “the highest reliable estimate of deaths,” while the best estimate reflects the most reliable estimate (Högbladh 2022, p. 5). The GED gives the number of deaths for both parties of a dyad, the number of civilian fatalities, and the number of people killed whose status is unknown. These differentiated numbers provide the best estimate (Högbladh 2022, p. 11). The information on the victims’ status is one reason why most researchers prefer using best estimates. The GED relies “on three sets of sources: 1. global newswire reporting, 2. monitoring and translation of local news performed by the BBC, 3. secondary sources” (Högbladh 2022, p. 12). About one-fifth of events in the compilation are based on “non-media sources” (Dietrich and Eck 2020a, p. 1048).

Previous studies on reporting by the GED have yielded diverging results. Weidmann matches events in Afghanistan in 2008 and 2009 considered by the GED and the Dataset on Significant Activities based on military reports. He concludes: “Casualty numbers are reported with a high level of precision, and under- versus overreporting is roughly balanced and low in magnitude” (Weidmann 2015, p. 1146). Otto (2013, p. 562) also investigates UCDP data on Afghanistan in 2009. According to her, the lack of information on many incidents “may result in undercounting fatalities from one-sided violence.” A study on the UCDP’s coverage of South Sudan warns that “precise point estimates about the causes and consequences of violence may be impossible using newswire data” (Dawkins 2020, p. 1113). As seen, the GED relies strongly on newswire reports.

With regard to the coverage of the temporal and spatial variation of deadly violence, previous studies refer to the importance of media access to the conflict area as regulated by the warring parties, to access impeded by bad infrastructure, to varying levels of media attention, to the capability of media to process information, to the role of international missions, and to the GED coding rules.

“Media are a part of the battlefield” (Öberg and Sollenberg 2011, p. 60). The parties to the conflict have a strong interest in what is reported and the way it is reported (Dawkins 2020, p. 1110). They influence the coverage of the conflict by national and international media by presenting, mispresenting, or withholding information, by ensuring or restricting media freedom or by facilitating, impeding, or denying access to locations in which battles or attacks on civilians occur. Parties to the conflict know that media reporting can influence the resolve within their own ranks as well as their national, transnational or international support. For instance, a warring party can hope to benefit from media reporting on locations in which its enemy killed civilians. Conversely, it tries to impede access to locations where it lost many combatants or committed war crimes. The extent of reporting fatalities varies with the conflicting parties’ interests and the accessibility of the conflict. Unequal access to territory can, inter alia, imply that the fatalities inflicted on one party are better covered than the deaths of the other conflict party.

Media access to conflict areas also depends on the available means of transport. Journalists often lack time or money for overcoming the “tyranny of geography” and for travelling to remote areas (Moeller 1999, pp. 27–28). Thus, an event’s location influences whether the incident is reported by media and covered by the UCDP. Price and Ball (2015, p. 264) state: “We have seen countless examples in our own work: violence in urban areas may be more visible to conventional media sources.”

Besides media access to conflict areas, media attention to a conflict also has to be considered. This attention varies over time because media have to select which events they report (Öberg and Sollenberg 2011, p. 53). The coverage of the conflict has to compete with other topics and some conflict phases seem to be more relevant for media reporting than others. “[C]hanges are reported, while the status quo is not” and “worsening of situations and extraordinarily bad or shocking events are over-represented” (Öberg and Sollenberg 2011, pp. 58–59). Conflict intensity also plays a role. The more destructive a conflict, the less it can be ignored.

Media have a limited capability to process information on a conflict. “[E]vents with many deaths tend to be captured by the data-gathering system more readily than events with a small number of deaths” (Jewell et al. 2018, p. 392). Incidents with more fatalities are more likely to be witnessed, reported by media, and therefore considered by the GED. An event size bias seems particularly likely when many events occur at the same time. Considering a large number of simultaneous events, media tend to focus on those with more fatalities. However, to consider a bias related to the number of simultaneous events can be useful for its own sake. The more events on the same day, the more likely the reporting channel is clogged so that a larger part of events remains un(der)reported, even if of the same size.

Moreover, the coverage of conflict fatalities is influenced by the deployment of an international mission. According to Chojnacki et al. (2012, p. 387), “the interest of international media … increases with a great power military intervention or the involvement of UN-led multilateral force.” This increased attention affects the chances of an event making it into the news and, by extension, into the GED. It seems acceptable to generalize this consideration to all peace operations and observer missions. Their deployment affects conflict coverage in yet another way. Peacekeepers and observers enlarge the number of people who can witness conflict-related violence or obtain reports on such events. They may get access to areas that journalists and other actors cannot enter. Reporting of conflict deaths by international missions can make a difference especially when the violence is widespread and intense.

A final consideration relates to the coding practice. “For an event to be included in the GED, the UCDP needs at a minimum to be able to identify the participants” (Dietrich and Eck 2020b, p. 2).Footnote 3 This “creates a selection bias toward well-documented events” (Chojnacki et al. 2012, p. 395).

The mentioned sources of inconsistencies and biases in reporting fatalities cannot be strictly separated from one another. For instance, good documentation of an event is more likely in urban areas, in the presence of international observers, and when only a few events occur at the same time.

In light of the outlined considerations, the extent of reporting fatalities cannot be expected to generally remain constant. Objections 1 and 2 against the GED summarize this concern. Objection 1 addresses the temporal distribution of deaths, whereas Objection 2 focuses on their spatial distribution. These objections refer to the coverage rate indicating how many of the fatalities documented by the Kosovo Memory Book are reported by the GED.

Objection 1:

The coverage rate of monthly fatalities by the GED varies widely over time and thereby misrepresents the course of the conflict.

Objection 2:

GED’s coverage of conflict-related deaths varies widely across municipalities, therefore misrepresenting the spatial distribution of fatalities.

Further objections focus on individual sources of biases, namely on potential event size bias, bias related to a small number of events on the same day, and deployment bias. I do not state an objection on an urban bias, because the information on the location of most events is insufficient for a corresponding assessment.

Objection 3:

Events in which many people are killed are better covered by the GED than events with fewer fatalities.

Objection 4:

Events are more likely to be ignored by the GED when there were many other events on the same day.

Objection 5:

The deployment of international observers or peace missions increases the rate of fatalities covered by the GED.

3 The Kosovo Memory Book as a yardstick

The Kosovo Memory Book was compiled by the Humanitarian Law Centre in Belgrade and the Humanitarian Law Centre Kosovo (Humanitarian Law Centre and Humanitarian Law Centre Kosovo 2011). The web address http://www.kosovskaknjigapamcenja.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/eng.xls provides access to an Excel file that lists not events but individual victims. The authors of the Kosovo Memory Book obtained information on victims

“by collecting witness statements, consulting court judgments, as well as by evaluating other sources such as reports by human rights organizations, the Serbian police or the military. … [A]t least two independent sources have to confirm a connection to the war, unless a court judgment is available on a given victim case.” (Krüger and Ball 2014: 28–29)

The Kosovo Memory Book documents people killed in Kosovo or outside this disputed region in the course of and due to the conflict. It presents the victims’ personal data: their name, the first names of their parents, their gender, date and place of birth, place of residence, ethnicity, and whether they were a civilian or a member of an armed formation. Each entry also includes data on the location and the date of death. The Kosovo Memory Book covers the period from 1998 to 2000 and differentiates between killings (11,536), deaths otherwise caused by war (316), and disappearances (1696). In the following, only killings are considered.

As highlighted by Spagat (2014, p. 16), the fatality data in the Kosovo Memory Book are corroborated by a household survey (Spiegel and Salama 2000). A study using multiple systems estimation (Ball et al. 2002) also closely corresponds to the information in the Kosovo Memory Book. An evaluation of this book concludes that “it is very unlikely that there are more than a few tens of undocumented deaths” (Krüger and Ball 2014, p. 59). With more than 99% of all deaths documented, the Kosovo Memory Book falls only narrowly short of providing exhaustive coverage. It would be unrealistic to expect that the information on the date and location of death is correct for every victim. Overall, however, the Kosovo Memory Book represents what really happened more closely than the GED does.

The GED includes battle-related events only where the organized actors on both sides are known and it includes one-sided violence against civilians only where the perpetrating organization is known. In contrast, the Kosovo Memory Book neither reports whether a death was related to battle or to one-sided violence against civilians nor presents information on the perpetrator. Thus, skeptics can argue that the killings documented in the Kosovo Memory Book are not necessarily related to organized violence but can include personally motivated murders despite the requirement to verify “a connection to the war.” These differences between the GED and the Kosovo Memory Book are particularly relevant in the phase of the conflict after the NATO had signed separate agreements with the warring parties and ended its airstrikes in June 1999. The period from July 1999 onwards was characterized by “revenge and reprisal violence” (Boyle 2010, pp. 198–203). Whether many of these events were cases of organized violence at all is not clear. The GED reports only two further deaths in this period, whereas the Kosovo Memory Book lists 606 killings. Restricting comparison of the two sources to the period from 1 January 1998 to 30 June 1999 ensures that the focus is kept on organized violence.

Table 1 shows the total number of direct deaths and the proportion of fatalities in the Kosovo Memory Book covered by the GED.Footnote 4 While the best estimates in the GED amount to one-third of the killings reported by the Kosovo Memory Book, the high estimates cover 80.5% of the fatalities.

Skeptics can object that excluding developments after June 1999 is not enough to make the Kosovo Memory Book and the GED comparable. In their view, without reporting the perpetrator, the Kosovo Memory Book is susceptible to erroneously categorizing killings with a personal motive as organized violence related to the conflict. To address this assumption I examine whether the differences in the reported numbers of fatalities can be explained by the consideration of homicides have such a personal motive. As shown in the Online Appendix, it is implausible that the higher number of fatalities in the Kosovo Memory Book can largely be attributed to the incorrect categorization of killings. To explain the difference of several thousand deaths, a highly unrealistic homicide rate would have been needed. The Kosovo Memory Book can thus serve as a yardstick for assessing the GED.

In the following, the five objections against the GED will be assessed separately and in a descriptive manner because regression analysis is not feasible in a meaningful way.Footnote 5 For the sake of clarity details on the operationalization are presented in the respective sub-section that addresses an objection or in the Online Appendix. All steps in the comparison consider the best estimates and the high estimates in the GED 22.1.

4 The GED in comparison with the Kosovo Memory Book

4.1 The temporal variation of deadly violence

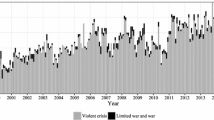

According to Objection 1, the extent of the deviation of the GED from the fatality data in the Kosovo Memory Book varies over time. Because many studies analyze fatality data on a monthly basis, I compare the Uppsala data with the information in the Kosovo Memory Book month by month. I use the absolute number of fatalities.

Every entry in the Kosovo Memory Book assigns the date of death to a calendar month. By contrast, 1511 of the 3629 fatalities in the GED best estimates (41.6%) are reported in 21 “multi-month events” in which the end date refers to another calendar month than the start date. In the high estimates, multi-month events cover 2029 of the 8801 deaths (23.1%).Footnote 6 Many GED users do not state how they cope with multi-months events but some of the studies cited in the introduction outline their approach. While Hultman and Peksen (2017, p. 1336, note 2) assign all deaths to the month of the start date, Ruhe (2020, p. 692) assigns all fatalities to the month of the end date. I distribute the deaths stemming from multi-month events (MME) evenly over time. If 40 people were killed in an event from 1 April 1998 to 10 May 1998, 30 deaths are assigned to April and 10 to May. As the Online Appendix shows, this approach better represents the temporal variation of deadly violence in Kosovo than do alternative options.

Figure 1 shows the monthly number of deaths. According to the Kosovo Memory Book, violence peaked for the first time between July and September 1998 and drastically escalated during the NATO intervention from the end of March 1999 to the first third of June 1999. GED’s high estimates as well as the best estimates show the escalation in spring 1999. In contrast to the best estimates the high estimates also mirror the escalation in summer 1998.

Not only the absolute level of deadly violence is relevant but also its change compared with the month before. In all 17 months available for evaluation, the GED best estimates correctly report if an increase or reduction in deadly violence occurred compared to the previous month. The high estimates do so for 16 out of 17 months.

Figure 2 illustrates the absolute difference between the monthly death toll in the GED estimates and in the Kosovo Memory Book. Strikingly, the GED’s underreporting is worst for the conflict phase of highest intensity from March to June 1999. The reporting scheme was overburdened by the high number of events in this period.

Although in total the GED reports fewer fatalities than the Kosovo Memory Book, its best estimates and even more so its high estimates overreport deaths for most months in 1998. This overreporting can be explained by large multi-month events which include deaths also covered by other entries.

4.2 The spatial variation of deadly violence

Objection 2 states that the GED misrepresents the spatial distribution of conflict-related deaths. In the Kosovo Memory Book, the respective number of fatalities in the course of the conflict can be ascertained by filtering based on municipality. In the GED, the information needed for identifying the municipality in which an event occurred is not always presented in the same column. Thus, I assess the data in the following columns: “where_coordinates,” “where_description,” “adm_1,” and “adm_2” (first and second order administrative division). If this is not helpful, I identify the municipality by using information on its longitude and latitude.

With only ten exceptions,Footnote 7 the Kosovo Memory Book assigns all people killed to a municipality of death. In the GED, a high proportion of fatalities is reported for categories such as “Kosovo,” with 942 deaths in the best estimates and 2310 in the high estimates. Events with no precise location came to a total of 1625 out of 3629 fatalities in the best estimates (44.8%) and 3394 out of 8801 (38.6%) deaths in the high estimates.

Figure 3 depicts municipalities in Kosovo and the absolute number of fatalities. Non-localized events are assigned proportionally to the number of residents in a municipality.Footnote 8

The level of deadly violence across Kosovo. (The maps were adapted by the author from the map at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Municipalities_of_Kosovo.svg, published under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ and created by “Cradel” https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Cradel)

The GED’s high estimates more accurately mirror the spatial variation of deadly violence than the best estimates. The former better highlight that the western, central, and northeastern parts of Kosovo were particularly affected. While in total the high estimates illustrate the spatial distribution of fatalities fairly well, they underreport the extent of killing by more than 600 fatalities in Gllogoc/Glogovac and by almost 700 deaths in Skënderaj/Srbica. Nevertheless, in a rank correlation of the Kosovo Memory Book data and the information in the GED, Spearman’s rho is 0.87 for the best estimates and 0.92 for the high estimates. In sum, the GED presents the spatial distribution of conflict-related fatalities surprisingly well.

When I compiled the data for Fig. 3, I noticed that events outside Kosovo seemed to be disproportionally considered. Table 2 confirms this by comparing the coverage rates for Kosovo and the rest of Serbia and Montenegro.

The details of the events outside Kosovo show that most of them relate to NATO airstrikes. Presumably, the victims of these airstrikes received greater attention, because they were more difficult to deny or conceal and Belgrade was particularly interested in presenting them to the public in order to delegitimize NATO’s Operation Allied Force.

4.3 Size and number of events

To assess Objection 3, that events with many fatalities are more likely to be considered by the GED than smaller incidents, I transform the name-by-name information in the Kosovo Memory Book into events (see the Online Appendix). The almost 11,000 entries in the Kosovo Memory Book for the period January 1998–June 1999 are attributed to roughly 3500 events. The few entries in the Kosovo Memory Book without precise information on the location are excluded.

Of all events based on the Kosovo Memory Book, it was possible to match 6% with an event in the GED when the best estimates are used and 10.4% of all events could be matched with the high estimates. The best estimates of these matched events add up to 1556 fatalities, the high estimates to 4108 deaths. Note that the GED includes about 570 events in the conflict over Kosovo.

Figure 4 assigns all events derived from the Kosovo Memory Book into one of six categories of the extent of deadly violence. As the left panel shows, the more fatalities in an event, the more likely it is that the GED considers the event at all. The right panel documents that events with more fatalities tend to be better covered by both types of estimates in the GED than are smaller events. In sum, I find evidence for an event size bias.

According to Objection 4, the GED tends to exclude an individual event when on the same day many other events occurred. Indeed, as Fig. 5 shows, the proportion of events matched by the GED is higher when the Kosovo Memory Book documents only a few other events on the same day. The trend, however, is not as clear as the with event size bias. Thus, there is weaker evidence for bias related to a small number of events on the same day.

4.4 International observers or peace missions

According to Objection 5, the presence of international observers or peace missions increases the extent to which the GED covers direct conflict deaths. To check this, the coverage rate in conflict phases with such a presence is compared with the rate in periods without such deployments. There were two conflict phases without and two phases with an international presence. On 6 July 1998, the Kosovo Diplomatic Observer Mission began (UN Secretary-General 1998a, Annex I, para. 10). In December 1998, it consisted of 217 observers (UN Secretary-General 1998b, Annex I, para. 28). Its task was to “observe and report on … [s]ecurity conditions and activities in Kosovo.”Footnote 9 The mission’s coordination was located in Prishtinë/Priština, while other centers were based in Pejë/Peć, Prizren, Mitrovicë/Kosovska Mitrovica, and Rahovec/Orahovac.Footnote 10

On 16 October 1998, the Chairman-in-Office of the Organization for Cooperation and Security in Europe (OSCE) signed an agreement with Yugoslavia’s Foreign Minister that provided for the deployment of the Kosovo Verification Mission. This mission had the responsibility to “verify compliance by all parties in Kosovo with UN Security Council Resolution 1199” (Agreement on the OSCE Kosovo Verification Mission 1998, para. II.1) which had demanded “that all parties … immediately cease hostilities and maintain a ceasefire in Kosovo” (UN Security Council 1999, paras. 1 and 3). On 25 October 1998, the OSCE established the Kosovo Verification Mission (Loquai 2000, p. 81) which three months later had 1826 members (UN Secretary-General 1999, p. 14). On 20 March 1999, several days before the NATO airstrikes started, both missions withdrew to Albania and to what is now North Macedonia (Loquai 2000, p. 89). Following Resolution 1244 and the end of NATO’s Operation Allied Force, strong military and civilian missions were established in Kosovo from 12 June 1999 onwards. Table 3 compares the coverage rates by the GED for the four phases. In light of Objection 5 the coverage rate should be higher for periods with such deployments than for other periods.

According to the GED’s best estimates, the coverage rate of conflict deaths is hardly affected by international deployment (32.8% vs. 34.8%). But when the high estimates are used, the coverage rate is clearly higher for the phases with such a presence, specifically 101.1% compared with 75.7%. Table 3, however, requires a more detailed discussion. To start with, it can be questioned whether the brief Phase 4 should be considered at all. Comparing only Phase 2 to the Phases 1 and 3, the coverage rate with international deployment is higher for the best estimates (41.9% compared with 32.8%) as well as for the high estimates (109.2% compared with 75.7%). This may suggest higher coverage of conflict deaths when international missions are present.

But the difference between coverage rates mentioned largely results from Phase 3 in which the intensity drastically increased and the degree of underreporting amounts to several thousand fatalities. Media coverage being overwhelmed by a huge number of events may be a far more important factor in the massive underreporting of fatalities in Phase 3 than the absence of observers.

To examine a potential deployment bias further, I consider the spatial and temporal variation of coverage rates with regard to the centers of the observer missions. If a deployment bias really existed, the coverage rate for the sub-phase with more observers should not be lower than for the sub-phase with fewer observers. However, this is the case, as shown in the Online Appendix.

In sum, there is no convincing evidence for a deployment bias.

5 Conclusion

Many researchers use the GED to analyze the temporal and spatial distribution of deadly violence across cases. This research note compares the GED and the Kosovo Memory Book to assess how well the Uppsala data cover conflict-related fatalities. There is evidence for an event size bias in the GED and, to lesser extent, for a larger proportion of events that are ignored when many other events occur on the same day. Moreover, conflict-related deaths outside Kosovo are considered disproportionally by the GED. In contrast, there is no convincing evidence for an increased coverage of fatalities when international observers are present. If such a deployment bias exists, studies possibly underestimate the violence-reducing effect of peace missions. Despite the problems mentioned, GED’s high estimates mirror the temporal variation of deadly violence in Kosovo fairly well while also representing the spatial variation of deadly violence relatively well. This positive assessment, at least to a considerable degree, depends on two deviations from standard practice. It also considers the high estimates, whereas previous research has preferred using the best estimates. Furthermore, fatalities in multi-month events and non-localized events are assigned proportionally. Assignment in this way can be done for a single case with relative ease but would be a complex task for cross-case analysis.

To test whether the best or high estimates represent the temporal and spatial distribution of fatalities well enough or whether the observed inconsistencies and biases distort empirical results, a replication study using the GED data instead of the Kosovo Memory Book data would be helpful. Regrettably, I found no published paper in which fatality data are important and for which replication files are available. However, I was able to replicate the study by Costalli and Moro (2012) on the severity of war violence in the municipalities of Bosnia-Herzegovina. I replaced their data provided by the Bosnian Book of the Dead (Tokača 2012) with the data in the GED 20.1, the last version without reference to the Bosnian Book of the Dead. The GED 20.1 did not represent the temporal and spatial distribution of deadly violence in Bosnia-Herzegovina as well as the GED 22.1 documents fatalities in Kosovo. The worst phase of escalation in Bosnia-Herzegovina was not mirrored in the GED data and well-known hotspots of lethal violence remained unidentified. Nevertheless, these data could replicate the results for the most important variables, namely for the ethnic composition of the municipalities. For other variables the findings were the opposite of those of the original study.

Can inconsistencies and biases be expected to be smaller or larger in other conflicts than in Kosovo? In the selected case, there was a relatively small conflict area with a large number of people reporting about a short war. Thus, the proportion of uncovered or underrepresented periods and locations is presumably smaller than elsewhere. Additionally, Kosovo is relatively well documented beyond news reporting, for instance by the rich academic literature or the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). On the other hand, the selected conflict took place in the 1990s when cellphones and social media were less readily available than in recent years. These means of communication make it more likely that a message on a lethal event will reach journalists or other observers (Weidmann 2016). Multi-month events are much more common in the selected case than on the average in all conflicts. When it comes to the proportion of non-localized events, Kosovo even represents an extreme case, as the Online Appendix shows. Overall, inconsistencies and biases in reporting fatalities are likely to be found in other conflicts. Further comparison of the GED with memory books on other conflicts would help assess how widespread such problems are.

I conclude with some recommendations. GED users are encouraged to state how they address multi-month events and non-localized events. In light of the findings for Kosovo some readers may prefer using GED’s high estimates instead of the best estimates because they provide a more accurate picture. However, I hesitate to generalize from Kosovo, as here the difference between the best estimates and high estimates is considerably larger than in the entire GED (see the Online Appendix). For Bosnia-Herzegovina the high estimates hardly improved the results. Moreover, when they deviate from the best estimates, the high estimates do not distinguish military and civilian deaths and thus do not permit a focus on one-sided violence against civilians.

As indicated, starting with version 21, the GED presents more accurate data on Bosnia-Herzegovina than before. It is advisable for the UCDP to continue efforts to also improve the data on terminated conflicts in order to reduce the number and size of multi-month events and non-localized events. To compensate for inconsistencies and biases related to media reporting, the GED could try to include secondary sources in a more systematic way. Remarkably, with regard to Kosovo, the GED 22.1 does not refer to any ICTY hearing or judgement.

Notes

Consequently, there is no event in the GED without data on “side_a” and “side_b”.

I consider the following dyads in “Serbia (Yugoslavia)” and neighboring countries: “Government of Serbia (Yugoslavia)—UCK” (dyad_new_id 868) and “Government of Serbia (Yugoslavia)—civilians” (dyad_new_id 917). The GED does not include a “UCK—civilians” dyad.

I intensively checked whether the data that match events in the GED to information in the Kosovo Memory Book create a basis for a linear regression with respect to how many fatalities are covered by the GED. Two-thirds of the events in the GED can be matched to events based on the Kosovo Memory Book. These matched events include not more than 43.5% of all deaths reported by the GED’s best estimates and 46.7% of all fatalities in the high estimates. I also considered conducting a logistic regression on the question of which types of events GED tends to incorporate or ignore. Despite a generous approach, only a small fraction of all events based on the Kosovo Memory Book can be matched to an event in the GED. In many of these few matched events the event size reported by the GED drastically deviates from the event size derived from the Kosovo Memory Book.

For instance, the event with the ID 218008 (1 January 1998–23 December 1998) includes 409 deaths (best estimates) respectively 700 deaths (high estimates).

Nine in Kosovo, one in Albania.

Since the last pre-war census in 1991 was boycotted by the Albanians (Musaj 2015, p. 85), I use data from the 2011 census in Kosovo available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Municipalities_of_Kosovo. The Online Appendix presents more details.

References

Agreement on the OSCE Kosovo verification mission. 1998. https://phdn.org/archives/www.ess.uwe.ac.uk/Kosovo/Kosovo-Documents3.htm. Accessed 10 July 2023

Ball, Patrick, Wendy Betts, Fritz Scheuren, Jana Dudukovich, and Jana Asher. 2002. Killings and refugee flow in Kosovo March–June 1999. A report to the international tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, Washington, DC. https://www.icty.org/x/file/About/OTP/War_Demographics/en/s_milosevic_kosovo_020103.pdf. Accessed 10 July 2023.

Boyle, Michael J. 2010. Revenge and reprisal violence in Kosovo. Conflict, Security and Development 10(2):189–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/14678801003665968.

Chojnacki, Sven, Christian Ickler, Michael Spies, and John Wiesel. 2012. Event data on armed conflict and security: new perspectives, old challenges, and some solutions. International Interactions 38(4):382–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2012.696981.

Costalli, Stefano, and Francesco Niccolò Moro. 2012. Ethnicity and strategy in the Bosnian civil war: explanations for the severity of violence in Bosnian municipalities. Journal of Peace Research 49(6):801–815. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343312453593.

Dawkins, Sophia. 2020. The problem of the missing dead. Journal of Peace Research 58(5):1098–1116. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343320962159.

Dietrich, Nick, and Kristine Eck. 2020a. Known unknowns: media bias in the reporting of political violence. International Interactions 46(6):1043–1060. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2020.1814758.

Dietrich, Nick, and Kristine Eck. 2020b. Online appendix for “Known unknowns: media bias in the reporting of political violence”. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/suppl/10.1080/03050629.2020.1814758/suppl_file/gini_a_1814758_sm3079.docx. Accessed 10 July 2023.

Fjelde, Hanne, Lisa Hultman, and Desirée Nilsson. 2019. Protection through presence: UN peacekeeping and the costs of targeting civilians. International Organization 73(1):103–131. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818318000346.

Hawkins, Virgil. 2002. The other side of the CNN factor: the media and conflict. Journalism Studies 3(2):225–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700220129991.

Högbladh, Stina. 2022. UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset Codebook version 22.1, Department of Peace and Conflict Research, Uppsala University. https://ucdp.uu.se/downloads/ged/ged221.pdf. Accessed 10 July 2023.

Hultman, Lisa, and Dursun Peksen. 2017. Successful or counterproductive coercion? The effect of international sanctions on conflict intensity. Journal of Conflict Resolution 61(6):1315–1339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002715603453.

Humanitarian Law Centre, and Humanitarian Law Centre Kosovo. 2011. Kosovo Memory Book 1998–2000. http://www.kosovskaknjigapamcenja.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/eng.xls. Accessed 10 July 2023.

Jewell, Nicholas P., Michael Spagat, and Britta L. Jewell. 2018. Accounting for civilian casualties: from the past to the future. Social Science History 42(Fall):379–410. https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2018.9.

Krause, Keith. 2017. Bodies count: the politics and practices of war and violent death data. Human Remains and Violence 3(1):90–115. https://doi.org/10.7227/HRV.3.1.7.

Krüger, Jule, and Patrick Ball. 2014. Evaluation of the database of the Kosovo Memory Book. https://hrdag.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Evaluation_of_the_Database_KMB-2014.pdf. Accessed 10 July 2023.

Loquai, Heinz. 2000. Kosovo—A misses opportunity for a peaceful solution to the conflict? In OSCE yearbook 1999, ed. IFSH, 79–90. Baden-Baden: Nomos. https://ifsh.de/file-CORE/documents/yearbook/english/99/Loquai.pdf.

Moeller, Susan D. 1999. Compassion fatigue. How the media sell disease, famine, war and death. New York, London: Routledge.

Musaj, Mehmet. 2015. Kosovo 2011 census: contested census within a contested state. Contemporary Southeastern Europe 2(2):84–98. http://www.contemporarysee.org/sites/default/files/papers/musaj_kos_census.pdf.

Öberg, Magnus, and Margareta Sollenberg. 2011. Gathering conflict information using news resources. In Understanding peace research: methods and challenges, ed. Kristine Höglund, Magnus Öberg, 47–73. London: Routledge.

Otto, Sabine. 2013. Coding one-sided violence from media reports. Cooperation and Conflict 48(4):556–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010836713507668.

Price, Megan, and Patrick Ball. 2015. Selection bias and the statistical patterns of mortality in conflict. Statistical Journal of the IAOS 31:263–272. https://doi.org/10.3233/SJI-150899.

Ruhe, Constantin. 2020. Impeding fatal violence through third-party diplomacy: the effect of mediation on conflict intensity. Journal of Peace Research 58(4):687–701. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343320930072.

Spagat, Michael. 2014. A triumph of remembering: Kosovo Memory Book. http://www.kosovomemorybook.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Michael-_Spagat_Evaluation_of_the_Database_KMB_December_10_2014.pdf. Accessed 10 July 2023.

Spiegel, Paul B., and Peter Salama. 2000. War and mortality in Kosovo, 1998–99: an epidemiological testimony. Lancet 355:2204–2209. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02404-1.

Sundberg, Ralph, and Erik Melander. 2013. Introducing the UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset. Journal of Peace Research 50(4):523–532. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343313484347.

Tokača, Mirsad. 2012. The Bosnian book of the dead. Human losses in Bosnia and Herzegovina 1991–1995, 4 volumes. Sarajevo: Istraživačko dokumentacioni centar Sarajevo and Fond za humanitarno pravo Beograd. http://mnemos.ba/Files/Books/TOM%20I%20prelom%20A.pdf, http://mnemos.ba/Files/Books/TOM%20II%20Bosanska%20knjiga%20mrtvih%20FINAL.pdf, http://mnemos.ba/Files/Books/TOM%20III%20Bosanska%20knjiga%20mrtvih%20FINAL.pdf, http://mnemos.ba/Files/Books/TOM%20IV%20FINAL.pdf.

UN Secretary-General. 1998a. Report of the Secretary-General prepared pursuant to Security Council resolution 1160 (1998), S/1998/712. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N98/227/91/PDF/N9822791.pdf?OpenElement. Accessed 10 July 2023.

UN Secretary-General. 1998b. Report of the Secretary-General prepared pursuant to Security Council resolution 1160 (1998), 1199 (1998) and 1203 (1998) of the Security Council, S/1998/1221. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N98/404/20/PDF/N9840420.pdf?OpenElement. Accessed 10 July 2023.

UN Secretary-General. 1999. Report of the Secretary-General prepared pursuant to Security Council resolution 1160 (1998), 1199 (1998) and 1203 (1998) of the Security Council, S/1999/99. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N99/023/65/IMG/N9902365.pdf?OpenElement. Accessed 10 July 2023.

UN Security Council. 1999. Resolution 1199, S/RES/1199. http://unscr.com/en/resolutions/doc/1199. Accessed 10 July 2023.

Weidmann, Nils B. 2015. On the accuracy of media-based conflict event data. Journal of Conflict Resolution 59(6):1129–1149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002714530431.

Weidmann, Nils B. 2016. A closer look at reporting bias in conflict event data. American Journal of Political Science 60(1):206–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12196.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Felix S. Bethke, Matthias Dembinski, Felix Haass, Beate Jahn, Constantin Ruhe, and Ulrich Schneckener and the anonymous reviewer for constructive comments on earlier versions of this article and to Matthew Harris and Carla Welch for editing.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

T. Gromes declares that he has no competing interests.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gromes, T. Reporting of conflict fatalities in the UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset: insights from Kosovo. Z Vgl Polit Wiss 17, 189–206 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-023-00573-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-023-00573-9