Abstract

Despite severe degradation of the natural environment in Central and Eastern European countries under communist rule and its large mobilizing potential in the 1990s, only in a few of these countries did Green parties rise to long-term relevance for the political system. The economic, social and political legacies of the communist regimes influenced the majority of successful Green parties in the region to adopt a centrist (Czech Republic) or right-wing (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) approach. In this context, I analyse the process of institutionalisation of the Green Party in Poland, closest among the CEE Green parties to the left-libertarian model dominant in Western Europe, and compare it with other Green parties in the region. I demonstrate how the support of the European Green Party has allowed the party to survive and partially institutionalise, but it has not been sufficient to ensure political success.

Zusammenfassung

Trotz der starken ökologischen Verschlechterung in den mittel- und osteuropäischen Ländern unter kommunistischer Herrschaft und ihres großen Mobilisierungspotenzials in den neunziger Jahren, erlangten die grünen Parteien nur in einigen dieser Länder eine langfristige Relevanz für das politische System. Das wirtschaftliche, soziale und politische Erbe der kommunistischen Regime hat die meisten erfolgreichen Grünen in der Region dazu veranlasst, einen zentristischen (Tschechische Republik) oder einen rechtsgerichteten (Estland, Lettland, Litauen) Ansatz zu wählen. In diesem Zusammenhang analysiere ich den Prozess der Institutionalisierung der Grünen in Polen, der dem in Westeuropa vorherrschenden linksliberalen Modell unter den mittel- und osteuropäischen Grünen am nächsten kommt, und vergleiche ihn mit anderen grünen Parteien in der Region. Ich zeige, wie die Unterstützung der Europäischen Grünen das Überleben und die teilweise Institutionalisierung der Partei ermöglichte, aber nicht ausreichte, um den politischen Erfolg sicherzustellen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The gradual decline of communist regimes in Central and Eastern Europe (henceforth CEE) in the 1980s and their final collapse in the early 1990s have brought to life the multitude of social organizations and movements. The process of liberalisation of the regimes occurring in many countries of the Eastern bloc, albeit to a different degree, and the alleviation of the apparatus of state repression gave faith in the possibility of independent action and encouraged the citizens to join collective actions. Environmental movements were one of the strongest actors, present in each of the CEE countries in the form of numerous independent organizations. Owing to the weakening of state control, new possibilities emerged for activists to gather and distribute information on the environmental degradation in post-communist countries, establish contacts with Western European activists and create independent associations and, subsequently, political parties.

The greatest successes of the Green parties in post-communist Europe took place in the first years after transformation, when the environmental movement enjoyed the greatest support. Flattened income inequality and poor articulation of group economic interests highlighted the extra-economic issues, including the degradation of the natural environment, to the general public (Inglehart and Siemieńska 1988). However, while degradation of natural environment encompassed all the CEE countries under the communist rule and it has become a common source of social protest, only in few of them Green parties institutionalised well and rose to the long-term relevance for the political system.

This paper builds on the theory of party institutionalisation to analyse this phenomenon. I analyse the process of institutionalisation of the Polish Green party in comparative perspective of other environmental parties in post-communist CEE countries—here taken to comprise Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia—after the democratic transition. I explore how programmatic and strategic decisions at the party creation influenced its later institutionalisation regarding its actions, access to resources and political significance. I focus primarily on how choices regarding the ideological profile of the party (internal institutionalisation) influenced possibilities of its external institutionalisation including coalition and electoral potential and greatly reduced its chance of electoral success. I hypothesize that, due to the small number of post-materialist voters and low salience of environmental issues, there was no room for Green parties in the left-libertarian formula. Only those Green parties that emerged in the 1990s, which decided to merge environmentalist ideas with social conservatism and pro-market stance, had a chance to survive in the long-term and institutionalise. Instead, Green parties in CEE implementing the dominant in the Western Europe ideological model combining social economic policies with liberal socio-cultural stance, encountered a strong limitation in institutionalisation due to the difference of historical conditions and of the position of the main axes of competition in the party system between Western Europe and Central and Eastern Europe. The external source of legitimacy in the form of support received from the European Green Party (EGP) has helped them to survive and achieve a certain level of relevance for other political parties but it was not sufficient to become a long-term relevant actor.

Data sources for this paper come from a research project on the Polish Green Party conducted in 2004–2015. The research methods included regular surveys at official party congresses, interviews with key position holders, participatory observation, analysis of party documents, promotional materials and media coverage, and national and cross-national survey data analysis. As the empirical and theoretical literature on Green parties in East and Central Europe is limited, especially in Poland, this paper aims to fill the gap, providing an explanation of the pattern of institutionalisation of less well known member of the European Green party family. Few studies on Green parties in Central and Eastern Europe and—with exceptions—small electorates of these parties translate into difficulties in building a systematic framework on which terms all analysed parties are compared across each dimension of institutionalisation. Therefore, for comparative purposes, besides desk research, the 1999–2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey trend file (Bakker et al. 2015) and 2017 Chapel Hill Expert Flash Survey (Polk et al. 2017) were used to assess the positions of the parties in two-dimensional ideological space and their change in time. Although these surveys cover comparative data on the largest number of Green parties in CEE among other data sources, they still comprise only the largest parties excluding, among others, Polish Greens.

2 Theory of institutionalisation and Green parties

The institutionalisation of the political party is as a process of continuous, dynamic adaptation and stabilization resulting in the transition from loose, spontaneous initiatives to more organized ways of collective action. During this process an organization stabilizes (Panebianco 1988) and acquire significance and value (Huntington 1968). The changes within the organization, resulting from the need to adapt to changing environment or undertook as its own decision, make the party more resilient and strengthen it as an actor within the political system.

However, despite numerous works in the field, starting from the classic Political Parties. Their Organization and Activity in the Modern State by Duverger (1963) and Political Order in Changing Societies by Huntington (1968), through works of Janda (1980), Panebianco (1988), Mainwaring and Scully (1995), Levitsky (1998), Randall and Svåsand (2002), Harmel and Janda (2004) and many more ending with the newest work by Harmel et al. (2018) and Harmel and Svåsand (2019) there is no consensus on the precise meaning and measurement of institutionalisation. According to Levitsky (1998), who made a comprehensive review of theories of party institutionalisation, including those focusing on the formal rules (Tsebelis), bureaucratization (Wellhöfer), organizational stability (Janda), taken-for-grantedness (Jepperson), infusion with value (Selznick) or regularization of patterns of social interaction (O’Donnell), they can be divided into two categories: defining institutionalisation as an infusion of values or as routinisation of activities.

Randall and Svåsand (2002) merged these two aspects into internal institutionalisation dimension, while adding party reification on social and political level as external institutionalisation. In addition, durability and adaptability were separated as a third dimension by Harmel et al. (2018). Summarizing, in the multidimensional approach by Harmel et al. (2018), adopted in this paper, institutionalisation is conceptualized as ‘the process of acquiring the properties of a durable organisation which is valued in its own right and gaining the perceptions of others that it is such’ and consists of three, interconnected dimensions: internal institutionalisation, external institutionalisation and objective durability.

With few exceptions (Harmel and Robertson 1985; Randall and Svåsand 2002; Basedau and Stroh 2008; Bolleyer and Bytzek 2013), most of the theories of party institutionalisation focus on medium or large parties, primarily in institutionalised, long-standing democratic political systems. The collapse of communist regimes in Central and Eastern European countries, and Asian states of the former Soviet Union, as well as the wave of democratization of African countries in the 1990s, contributed to an increase in academic interests in the area of parties and party systems at early stages of development (Randall and Svåsand 2002). Their institutionalisation was being considered a key element of effective and long-term democratization and this resulted in the need to develop theoretic models of assessing the level of formalization and routinisation of the new parties in developing party systems.

However, in the majority of theories the focus is still set on the later stages of party institutionalisation, when parties already have substantial electoral support and parliamentary and/or governmental representation, while explaining the initial stages of development to a much lesser degree. This makes many key indicators of institutionalisation impossible to apply to small, extra-parliamentary parties, parties representing niche ideologies (see Janda 1980; Maor 1997; Meleshevich 2007) or before the party had obtained relevance for the political system. Therefore, within the canonical models of institutionalisation almost all small parties would be classified as poorly organized and not socially rooted, without indicating differences between them.

Putting the focus on indicators of institutionalisation at early stages of party development is particularly important in the analysis of a niche party family: Green parties, especially newly created ones or ones operating in an unfavourable environment, having problems getting wide recognisability and electoral support. Moreover, this party family, constituting a political representation of new social movements, is by definition resistant to institutionalisation, by maintaining low hierarchy, collective management and decision-making process and spontaneous actions. For this reason, it is necessary to move away from the classic indexes of institutionalisation based on party behaviour in legislatures and governments and using instead indicators regarding small parties or parties in the initial stages of development.

Notwithstanding, party founders have only limited possibilities of ensuring the success of their endeavour as the majority of constraints is imposed by external environment. Thereat, at the beginning, I briefly present the history of the development of environmental organizations and parties in CEE as a background for the creation of the Polish Green Party and grounds for key ideological and organizational choices made by founders at the party creation. Then, I analyse problems with its institutionalisation—in comparison with other Green parties in post-communist CEE—discussing key indicators of party institutionalisation which are applicable to small, niche parties: extra-parliamentary origins (Duverger 1963), penetration/territorial diffusion, source of legitimacy, access to selective benefits for the members and a type of leaders (Panebianco 1988); rootedness in organised social groups, quick electoral success, proportional electoral system and the emergence of a party at the founding of competitive elections (Rose and Mackie 1988), access to key resources (Poguntke et al. 2016), international integration (Weissenbach 2010), ideological coherence and value infusion among members and voters (Levitsky 1998), autonomy (Huntington 1968; Panebianco 1988) and durability (Rose and Mackie 1988; Janda 1980; Harmel et al. 2018).

3 Politicizing the environmental crisis after the communist period

Although first organisations promoting conservation of nature had existed in Central and Eastern Europe since the beginning of the 19th century (Tickle and Welsh 1998), they could not be described as social movements due to the small number of members. During the communist period, large state-sponsored and politically steered environmentalist organisations existed in most of the communist countries. The communist authorities created them from scratch or overtook previously independent organisations, which were reorganised in line with the party ideology. Although they provided ‘a limited room for quasi-independent activity at their margins’ (Fagan 2004) for involved citizens, they lacked the necessary grass-roots background and autonomy. Thus, the beginnings of the independent environmental social movements can be dated back to the early 1980s and linked to the process of liberalisation of the communist regimes.

The environmental movements were based on the fast-growing awareness of the ecological threats caused, inter alia, by prioritisation of the heavy industry by the communist government. Despite the sympathies towards anti-communist opposition of the vast majority of the activists, these organisations shared the same non-political nature, stemming from distrust of politics and unwillingness to enter conflicts with the authorities. ‘All social movements stressed that they didn’t undertake any political activity [as it] was the communist rulers’ most severe accusation’ (Hrynkiewicz 1990, p. 21–22). On the other hand, many political opponents of the regime became involved in the environmental movement because in this way they could oppose the authorities covertly, attacking not the very core of the system, but focusing on its failings in the peripheral areas of ideology. As Hicks (1996, p. 122) points out: ‘However salient, issues were ultimately weapons with which to discredit communist rule further and mobilize social opposition to the existing regime. Ecology was potentially a strong weapon. The state of Poland’s natural environment and lack of significant government action to halt its deterioration blatantly contradicted official claims of the constitutional right of all citizens to enjoy the natural environment’.

This gave the environmentalists a rare political opportunity. They could officially fulfil the recommendations of the Communist Party by criticizing the consequences of the party’s own decisions, which in turn enabled them to anchor their demands in the dominant political discourse. Similarly, Galbreath and Auers (2009, p. 336) observed that while in Latvia ‘it was still taboo to challenge the legitimacy of the Soviet state, there was room for collective dissent against specific problems, especially if they could be couched in Soviet political discourse’, and Jehlička and Kostelecký (1995, p. 209) argued that in the Czech Republic ‘the environment became more or less the main legal basis for opposition to the Communist regime (…). In consequence, many activists were primarily opponents of communism and only secondarily supporters of the environmental cause.’

Nonetheless, environmentalism became not only a fight against environmental degradation, but also a useful ideological umbrella for the fight against the totalitarian government in most of the Central and Eastern European countries. Widespread support for environmentalism and its role as a neutral shield allowing various ideological streams within opposition forces to jointly act against communist governments has made organizations and environmental movements a part of the broad anti-communist coalitions emerging at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s in the region. A joint start in the first free parliamentary elections of anti-communist forces enabled environmental activists to obtain their first seats in the CEE parliaments.

Latvian opposition against the USSR Council of Ministers’ plan to build a third dam on the Daugava and its successful cancellation in the 1987 resulted in formation of the Environmental Protection Club in the same year. The Latvian Green Party (Latvijas Zaļā partija, LZP), founded in 1990, secured 7 seats in parliamentary election in the same year and managed to achieve parliamentary representation in all subsequent elections except in 1998. In Estonia, plans for large-scale phosphate mining made by the Soviet central government gave rise to a wide environmental movement that merged environmental issues with national identity (Sikk and Andersen 2009). Soon after the formation of the Estonian Green Movement, two Green parties were created (Eesti Roheline Erakond, ERE and Eesti Roheline Partei, ERP) and in 1991 they merged into Estonian Greens (Eesti Rohelised, ER). In the parliamentary election of 1992 broad coalition of Estonian environmental political parties and organizations acquired a single mandate. The Ignalina nuclear power plant expansion plan started mass demonstration in Lithuania. In the 1990 election Lithuanian Green Party (Lietuvos žalioji partija, LZP) managed to secure four seats but later vanished from the party system.

In Czechoslovakia, the joint Czech and Slovak Green Party was formed in 1989, but in the parliamentary elections in the following year only the Slovak part managed to get six seats, although it was the Czech Greens who obtained higher percentage of votes. After the dissolution of Czechoslovakia, the Green Party in Slovakia (Strana zelených na Slovensku, SZS) divided and some members joined nationalist, pro-Mečiar, centre-right coalition obtaining one seat in the 1994 election, while the others became a part of the centre-left coalition and received two seats in 1994 and three seats in 1998 (Kopeček 2009). In the Czech Republic, support for the environmental movement was strong, especially in the most air-polluted regions: northern Bohemia and Moravia. In 1992 The Czech Green Party (Strana zelených, SZ), two years after formation of the first same-named party, managed to secure three parliamentary seats as a coalition partner within the Liberal and Social Union.

The protest against the construction of dams on the Danube became the key point of development for the Hungarian environmental movement. However, the right-wing Green Party of Hungary (Magyarországi Zöld Párt, MZP), founded in 1989, did not succeed in any national election. Its two main splitter parties: the centrist The Green Alternative (Zöld Alternatíva, ZA) and the left-wing Hungarian Social Green Party (Magyar Szociális Zöld Párt, MSZZP), and later successor the centrist Alliance of Green Democrats (Zöld Demokraták Szövetsége, ZDSZ) also did not succeed and their members joined other Green parties.

In Poland, it was an external factor that mobilised the environmental activists and supporters. The construction works on the first Polish nuclear power plant in Żarnowiec started in 1982, but in the beginning the protests against them were very mild and limited to sending letters to the authorities. They escalated very quickly after the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, which, considering large quantities of radioactive contamination released into the atmosphere over the USSR and Europe, constitutes the worst nuclear power plant disaster in history. In combination with the Polish authorities initially denying the catastrophe and later providing very little solid information, it sparkled panic and distrust towards the government among people and caused the unengaged observers to support the environmental movement. The activists, mostly from the Freedom and Peace (Wolność i Pokój, WiP) movement, petitioned the local communities, picketed from rooftops to evade and delay arrests, organised hunger protests and weekly demonstrations against Żarnowiec and the other proposed locations of nuclear plants (Klempicz) and waste management sites (Międzyrzecz, Różan). They received support from Lech Wałęsa and Solidarity as well as from local communist authorities and residents who carried out roadblocks in Żarnowiec using agricultural equipment, which led to project cancellation in 1989 (Waluszko 2013). The action against the Żarnowiec nuclear plant was not the first successful protest by the movement, but the most spectacular and most recognised one. Arguably, it was the large-scale action itself, engaging the information-demanding mass public, rather than the later positive outcome, that politicized the previously neutral environmental issues and turned its activists and supporters into political contestants and voters.

Due to the fall of the communist rule only few years after the Chernobyl disaster, anti-nuclear and environmental issues retained the high salience during the first few democratic elections. The Solidarity leaders held an ambivalent stance towards environmental issues, ranging from cooperation to forceful opposition, but mostly considering it of secondary importance against the economy. As a consequence, a number of independent initiatives arose within the environmental movement to gain political representation on their own. The first environmental organisations describing themselves as political parties came into being in 1988 and included: the Federation of the Greens, the Independent Party ‘The Green Movement’ and the Polish Green Party. In the first partially free parliamentary elections of 1989, three environmental activists got elected from Solidarity’s lists, but in the 1990 local elections there were already 13 independent environmentalist parties participating, cumulatively winning 31 seats (Hrynkiewicz 1990, pp. 49–51).

Unfortunately, the environmentalists’ potential to mobilise huge masses was largely wasted in subsequent years. Because of their unwillingness to find compromise, the attempts to create a unified representation of environmental organisations invariably failed. The final breakdown of the Polish environmental movement was clearly visible in the parliamentary elections of 1991, when several Green parties competed against each other (gaining over 2.0% of votes, but no seats), including the Polish Environmental Party ‘The Greens’, ‘Healthy Poland’—the Polish Ecological Union, the Independent Ecological Federation, a coalition of the Polish Environmental Party and the Polish Green Party (Gliński 1996). All of the above parties, except for the first one, were created in 1991, shortly before the elections and constituted a top-down political initiatives rather than political representations of local movements.

Environmentalists also participated in elections as a part of traditional political parties covering full right-left dimension: in May 1991 the Environmental Faction of the Democratic Union (UD; centre-right) and the Green Platform of the Alliance of Democratic Left (SLD; left-wing) were established; they were also competing from the lists of right-wing parties: Electoral Catholic Action and Christian Democrat Party (Gliński 1996). The 1993 changes of the electoral system, introducing a threshold of 5% and a less proportional electoral formula, and the 1997 changes to the Bill on Political Parties that increased the requirements set forth for newly created formations, further weakened the movement. The most successful initiative turned out to be the Environmental Forum of the Freedom Union (UW, centre-right, successor of UD), which managed to secure a few seats in the 1991, 1993 and 1997 elections, as well as a position of the vice-minister of environment for its leader, Radosław Gawlik (future leader of the Green Party) in 1997. The party’s devastating loss in the 2001 election started its fast demise and forced the environmentalists to search for an alternative political formula.

4 Two ideological paths

The quick loss of support by the Green parties after the first successes was a widely observed phenomenon in Central and Eastern Europe. Until the early 2000s all of them lost the parliamentary representation (although in Estonia, Latvia and Czech Republic they later managed to restore it). This was the case despite most of the parties fulfilling the set of factors proposed by Rose and Mackie (1988, p. 537) as increasing the chances of a nascent party becoming institutionalised: origin at the founding of competitive elections, contesting elections under proportional representation (except in Lithuania and Hungary with mixed electoral systems), party being based upon organized social group and initial success in winning votes.

Although these requirements were met by the newly created Green parties, the period following the democratic transition turned out to be unfavourable for the Greens. After the introduction of competitive elections, when the Communist parties, considered the main political enemy, were defeated or significantly weakened, the wide anti-communist coalitions crumbled due to ideological or personal differences. The newly emerging parties have emphasized in their programs the daily ills of people related to the economy, labour market and public services, pushing aside the issues of environmental protection as of secondary importance or, alternatively, incorporating environmentalists’ agenda into their own programs (Gliński 1996; Kopeček 2009). As protection of nature have become a widespread element of political programs of parties belonging to different political families, it posed a challenge regarding ideological coherence of Green parties. Their excessive ideological shifts either towards nationalism or socialism contributed to internal splits within the parties and resulted in the functioning of more than one Green party at some point in majority of analysed countries, which hindered the electoral decision of environmental-oriented voters and weakened the chances of these parties. Moreover, early environmental organizations encountered problems when their basic goals were partially achieved as the fall of communism also marked the end of prioritization of heavy industry and a decline in industrial production, which had the highest impact on the environment.

On the institutional level, along with the ongoing consolidation of party systems, the rules concerning party funding and access to the mass-media have become more restrictive. Together with higher registration requirements for electoral committees and higher electoral and natural thresholds, this contributed to the closure of the party systems, which in turn hindered new actors from entering it (cf. Ibenskas, Sikk 2017) and restricted articulation of niche ideologies. The majority of small parties devoid of stable financial support had little chance of becoming serious competitors in elections, as they were sometimes unable to even complete the administrative stage which was a prerequisite of taking part in elections.

The environmental parties have also encountered several additional problems absent in Western Europe. The most vital of them were the economic legacy of communist and transition periods, including the unmet material needs of a large part of the population, strong position of the agricultural and industrial sectors in the employment structure, lack of a large middle class, a low salience of environmental issues during the economic crisis (Kitschelt 1989; Poguntke 1993), and the social legacy of communism, including destruction of the fundamental social bonds, resulting in mistrust and suspiciousness of public activity, a lack of responsibility for the community, a sense of disempowerment, the inability to influence the political processes, and the reluctance towards participation in associations (Ekiert and Hanson 2003).

As a result, there was no post-materialist value change after the collapse of the communist regimes, which is considered crucial for the emergence of the environmental movements and Green parties (Müller-Rommel 1989; Abramson and Inglehart 1995; Grant, Tilley 2019). The percentages of post-materialists in post-communist societies not only were low just after the transition in comparison with Western European countries (5–10%, EVS 1990/1994), but in most of them decreased over time. The small number of post-materialist oriented voters in CEE was not enough to secure stable electoral support for Green parties.

Because of that, the Green parties of post-communist Europe created in the 1990s managed to institutionalise and achieve a long-term electoral success only when they have chosen to combine the environmental concerns with key political values of these societies: protection of national identity in the face of the growing economic and cultural domination of the West, national independence, foreign relations and ethnic divides, or economic modernization. In most cases, environment was framed in an ethnocentric way in their programmes as a source of national pride, not as a value in itself, combining environmentalism with nationalism. Hence, the engineering plans of the communist governments, damaging the natural environment, were perceived as a threat to national values, identity and international position.

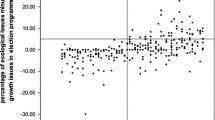

Figure 1 presents position of Green parties on the cosmopolitanism-nationalism scale, as defined in Chapel Hill Expert Survey (Bakker et al. 2015). The question about nationalism was used in two studies (in 2006 and 2014) and showed that the averages for Central and Eastern European countries (4.64 on a 0–10 scale) are higher than for the countries of Western (2.2) and Southern (3.79) Europe. Particularly high levels of nationalism were recorded in Latvia (ZZS) and Estonia (EER).

Party positions on a cosmopolitanism-nationalism scale. Green parties in CEE in black, SE in dark grey and WE in light grey. Source: 1999–2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey trend file (Bakker et al. 2015)

Moreover, the historical conditions bound together the main political dimensions of political competition: economic and socio-cultural, opposite to the type existing in Western European countries (socialism & socio-cultural liberalism versus economic liberalism & conservatism) in most post-communist states (economic liberalism & socio-cultural liberalism versus socialism & conservatism) (Kitschelt 1992; Marks et al. 2006), which further impeded the implementation of the Western variant of Green politics. Due to the high level of socio-cultural conservatism and a high salience of issues of national identity, majority of Green parties in CEE countries have included in their programs a traditional approach to gender roles, a reluctant attitude towards L the rights of LGBT people and ethnic minorities, in opposition to equality and non-discrimination standards for the Western European Green party family. As a part of anti-communist opposition, they usually adopted the liberal economic and pro-modernization approach. According to Chapel Hill Expert surveys, apart from the borderline case of Slovakia, only in three Central and Eastern European countries the main axis of competition is similar to Western European countries: in Slovenia, Estonia and Latvia (Marks et al. 2006; Rovny and Edwards 2012; Bakker et al. 2012).

These are the main reasons why most successful environmental parties in the region founded in the 1990s, in the Czech Republic, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, have chosen a predominantly free market oriented stance (cf. Sikk and Andersen 2009; Jehlička et al. 2011) and centrist (Czech Republic) or even right-wing (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) approach in the socio-cultural dimension. Positioning themselves beyond the major conflict axis, as in the case of the Polish Green Party, significantly limited the chances of electoral success and party institutionalisation. This makes the main difference compared to Green parties from Western Europe, most of which, despite program differences, have left-wing or centre-left stance (Bomberg 1998).

Despite the fact that they all belong to the European Greens, their resemblance to Western European counterparts in terms of identity and common program elements is limited. Especially in the case of Greens in the Baltic states, it can be stated that they share ‘little more than a name and a heightened sensitivity to environmental issues with its West European namesakes’ (Sikk and Andersen 2009, p. 249). The same applies to their voters: they tend to support economic development, even at the cost of environmental degradation, self-identify as right-wing, and have no specific socio-demographic background as well (Agarin 2009).

Figure 2 presents ideological positions of the Green parties in Western versus in Central and Eastern Europe as estimated by local experts in Chapel Hill Expert surveys in two-dimensional ideological space in years 1999–2017 (Bakker et al. 2015; Polk et al. 2017) (unfortunately, there is no comparable data covering positions of Green parties in CEE before the 1999 survey). The CEE Green parties are situated to the right of the West European parties both on economic left-right dimension, which refers to the party position regarding an economic role for government in the economy (0—extreme left, 10—extreme right), and on socio-cultural (galtan) dimension, which denotes the position of the party in terms of their views on personal freedoms and rights (0—libertarian/postmaterialist; 10—traditional/authoritarian). They tend to favour more the reduced economic role of the government (means on economic left-right: CEE 4.48, SE 3.82, WE 3.01) but rely on the government to be a moral authority on social and cultural issues (mean on socio-cultural dimension: CEE 3.55, SE 2.53; WE 1.86).

The second wave of Green parties emerged in the CEE countries (Hungary, Lithuania, Poland) during the 2000s and 2010s and was associated with the expansion of the European Union (Frankland 2016) and under heavy influence of ideology represented by the European Green Party. Among them, the Hungarian Politics Can Be Different (Lehet Más a Politika, LMP), created in 2009, was the most successful one. While the party didn’t secure any seats in the European Parliament, it managed to gather over 7% of votes in 2010 parliamentary elections and, despite the internal split in 2013, has maintained its presence in the parliament ever since, as a small opposition party. Although LPM ‘is not yet a ‘new-left’ party [as it] incorporates a few but fundamental incorporates a few but fundamental conservative elements, most notably a political focus on ‘communities’ and a far-reaching critique of the EU’ (Fábián 2010, p. 1007), its ideology is much more in line with the Western Green parties. The LMP splitter, Dialogue for Hungary (Párbeszéd Magyarországért, PM; since 2016: Dialogue [Párbeszéd], P), also won their own seats in national parliament (one in 2014 and three in 2018) and European parliament (one in 2014).

Apart from new parties, more ideologically closer to Western European counterparts than the environmental parties of the 1990s, changes have also occurred in existing parties. In 2006 both Czech and Slovak Green parties repositioned themselves, departing from the centre-right (and in the case of Slovakia, from nationalism) to positions much closer to the EGP (Fagan 2004; Kopeček 2009). In case of the Czech Greens, this move has brought a temporary success. After many terms as extra-parliamentary opposition, the party, following leadership and programmatic change made a comeback in 2006 securing six parliamentary seats and, thanks to unusual composition of the parliament—four cabinet positions. However, in subsequent elections they were unable to get any mandates. For the Slovak Greens, programmatic change did not improve the party relevance.

Moreover, some right-wing CEE Green parties created in the 1990s also managed to return to political systems. After an unsuccessful electoral campaign in 1998, the Latvian Green Party merged in 2002 with conservative Farmers Union into the centre-right Greens and Farmers Union (Zaļo un Zemnieku savienība, ZZS). The alliance, mixing green conservatism with agrarian ideology and socio-cultural conservatism, secured parliamentary representation in all of the subsequent six terms, of which four times it was part of a government coalition. The Greens even managed in 2004 to fill the post of prime minister and in 2015 the post of president of the country—the first Green politicians in these positions.

Additionally, the Estonian Green Party (Erakond Eestimaa Rohelised, EER) managed to re-register itself as a successor of ER—after nearly nine years of non-existence—before the 2007 parliamentary election and win six seats, but later dropped to an extra-parliamentary opposition. The Lithuanian Green Party (Lietuvos Žaliųjų Partija, LŽP) also managed to return to parliament after 22 years. The new party, founded in 2011, continued the line of old the LŽP and managed to secure one seat in parliament.

However, the most surprising success of the Green party was made by the Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union (Lietuvos valstiečių ir žaliųjų sąjunga, LVŽS). After the name change in 2012 (previous name: Lithuanian Peasant Popular Union) it had just one elected representative in the 2012 election, but it secured 54 out of 141 mandates in 2016, becoming the strongest political force in the parliament and a leader of government coalition. It also has one seat at European Parliament since 2014. The party offered a fuzzy, populist programme that combined ‘the hard left promise of radical change on socioeconomic issues and the far right conservative approach to identity politics, human rights, minority rights, gender equality, and refugees’ (Valentinavicius 2017, p. 19). It gained the support of voters from all the spectrum of electorate (Navickas 2017).

The Green Party in Poland, founded in 2003 initially under the name Zieloni 2004 (The Greens 2004), has achieved the worst results in the region. They never managed to win a parliamentary representation (although they persuaded in 2014 one MP of another party to join their ranks). In the following section, I present what reasons led to their lack of success and low political relevance, as well as the factors why they managed to survive as an organization in spite of this.

5 Institutionalisation without voters

For a long time, the creation of a left-libertarian Green party in Poland was blocked by the existence of a strong successor of the Communist party, whose platform was gradually enriched with a wide spectrum of the New Left demands, especially issues of women’s emancipation and equal rights of sexual minorities. SLD was able to present itself as a modern, pro-European, left-libertarian party due to its privileged position on the political scene, stemming from the acquisition of a large share of financial and real-estate resources of the former Communist party, its expanded structures formed of experienced and socialised members, as well as a closed segment of the electorate, consisting of communist period beneficiaries (Grabowska 2005), its network of personal assets on the intersection of the public sector, the party and the market, and conversion of political authority of the nomenklatura into its economic power (Staniszkis 1991) and a skilfully executed strategy of platform adjustment to the new political conditions (Grzymała-Busse 2002).

The founding of the Polish Greens was fostered by the loss of credibility of the then-ruling SLD, which, despite the incorporation of new social movements demands into their program, had done little to implement them. During its last term in power (2001–2005), riddled with corruption scandals and broken electoral promises, its support experienced a record fall from 41% to 11% in four years, which freed up space for a new left-wing actor. However, this major shock in the Polish political system was followed by two main right-wing parties claiming centre-left voters by successfully capturing key issues. The Civic Platform (PO) has taken over some issues of the left-wing socio-cultural program, such as civil liberties, women emancipation and decentralization. The Law and Justice (PiS) adjusted to conservative and pro-social voters by moving towards economic left-wing policies. This alteration of party system, which in subsequent years gradually expelled all left-wing parties from parliamentary representation, made the Green party unable to take advantage of the decline of the SLD.

The most successful Green party in the region—Hungarian Politics Can Be Different—has been created in similar circumstances, however there were key differences that impacted their actual success. First of all, Hungary has seen a major ecological crisis—the Baia Mara cyanide spill in 2000, which affected drinking water for 2.5 million Hungarians—in a relatively recent time frame. In addition, the party was created just before the 2009 European parliamentary elections, and its creation coincided with vacuum created by the meltdown of the socialist party (MSZP), the successor of the Hungarian Communist Party. Its loss of support was attributed mainly to widespread corruption scandals and, to a smaller extent, to the global economic crisis (Fábián 2010) and created a place for a new political force. LMP’s manifesto covered both environmental and liberal stances, but also strongly advocated the ‘clean hands’ (Frankland 2016, p. 67) approach in opposition to the current political parties. Similarly, although on a smaller scale, the electoral failure of the centre-right, economically and socially liberal Freedom Party in the Czech Republic created a place in the party system, which was taken over by Czech Greens.

Similarly to most of the Green parties, the process of formation of the Polish Green Party had a fully bottom-up character and was initiated spontaneously by a group of NGOs activists, in a way fitting Duverger’s (1963, p. xxx) model of the party of extra-parliamentary origin (a notable exception is the Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union, which was originally founded as a Lithuanian Peasant Party in 1990 as a resurrection of a pre-war party of the same name). Although during the initial period of development there were a few activists with parliamentary or governmental experience among the party members, they did not have a decisive influence on the party’s program and most of them withdrew from support fast.

Additionally, in respect to Panebianco’s distinction (1988) between types of territorial expansion of the organization: by penetration (the initiative comes from the ‘centre’, which stimulates the formation of local organizations) or in a spontaneous, decentralized, bottom-up way (expansion by diffusion—starting with grassroot-level connections between local political initiatives), the Polish Greens constitute an intermediate type with a bias toward territorial penetration. This feature is also typical of Green parties in which the dominant centre can be distinguished. Development by penetration results in stronger and better institutionalised parties. On the other hand, parties created top-down, especially initiated by the parliamentary faction, have wide access to state resources, which may weaken their mobilizing function and promote the use of state institutions and procedures as an alternative to the process of institutionalisation of the party.

The bottom-up formation of the party limited their access to key political resources affecting party institutionalisation in the initial phase: money, staff and members. Level of resources is partially predetermined by few factors related to party origin and party type (splitters typically have more resources than newly created parties, parties initiated by parliamentary factions have more than extra-parliamentary ones, parties built on mass membership fare better than niche parties, economically liberal parties have better chances to be financed by business organizations, etc.) and efficiency of party organizational and marketing strategies (Poguntke et al. 2016). Originating from new social movements, Polish Greens, as most of the Green parties in Central Europe, suffered from serious deficiencies in material resources, which slowed down party institutionalisation. In contrast, the parties in Baltic States, especially in Latvia in Lithuania, have been heavily relying financially on donations of wealthy individuals. The Latvian Greens are supported and financed by the mayor of Ventspils, ‘oligarch’ Aivars Lembergs, while Ramūnas Karbauskis, the LŽVS leader, is one of the richest people in Lithuania.

However, the shortage of resources encountered by Green parties—mostly in Poland, Czech Republic and Hungary—were partially compensated by another kind of resources that influence institutionalisation—access to social and political networks on national and international level (Weissenbach 2010). Of high advantage, especially for the Polish Greens, were their political networks within the family of Green parties. As the party electoral initiation was planned for the first Polish election to the European Parliament in 2004, it attracted the attention of the European Green Party aiming at enhancing its fraction in the European Parliament by parties from new EU-member states. The EGP was sharing valuable resources: a worldwide known brand and political platform, political experience, access to expertise in political campaign management, media and funding. The Green parties and the Green political think-tanks offered professional help to the founders of the new party, concerning methods of organisation, networking, building local structures, mobilising supporters and drafting the party’s platform.

The EGP actions had a huge impact, especially in the initial period, helping in establishing contacts with environmentalist organizations and Green Parties from other countries, especially from Germany. Support from the EGP also facilitated the organization of several conferences with Green political experts and activists, which resulted in media attention and greater party recognition. Outside of the EGP, the Polish Greens also received assistance in the promotion of their ideas and leaders from the Polish branch of the Heinrich Böll Foundation (HBS), a think-tank affiliated with the German Green Party. The patronage of HBS and endorsement from key activists of German Greens was crucial for strengthening the position of the Polish Greens among other political parties. In the similar way, these entities helped the Czech Greens—both in the 1990s, when Milan Horáček, German Greens MEP and the Chairman of the HBS in the Czech Republic helped was involved in the creation of the Czech Greens, and in 2006—after a change of program and leadership—when the party made a comeback to the parliament (Cordell and Hausvater 2006).

This brings us to another indicator critical in the initial phases of institutionalisation, which is the source of legitimacy of the party. It may be external—through the existence of the sponsor institution, or internal—without such influence. According to Panebianco (1988), when the party is legitimated by its sponsor organization, the sponsor is usually interested in maintaining control over the organization at the expense of limiting its growth. However, in case of EGP, it is a growth of sponsored organization that benefits the sponsor, as they are competing on different regional markets. In case of the Polish Greens, the influence of EGP could be interpreted twofold. On one hand, it greatly boosted the party growth in the initial period by sharing the indispensable resources. Moreover, membership in the European family of Green parties strengthened the party legitimacy and close relationship of the new party with then in-government German Greens helped to improve its relevance for other political actors in Poland. On the other hand, it influenced greatly ideological position of the party, impacting its further, irregular institutionalisation.

The foundation of the Polish Greens as a representation of several social movements was based on assumption that their ideologies can be combined under Green Politics umbrella. However, ideological conflicts hindered the party institutionalisation since the beginning. Among those, the most significant one concerned the clash between environmentalists and feminists regarding abortion. The environmental movement in the 1980s and 1990s was socio-culturally conservative and anti-communist. On the other hand, since in 1993 the radical Christian parties originating from democratic opposition forced in the parliament the change of law that strictly limited the possibility of abortion, the feminists were politically associated with the post-communist camp as its main political ally. Conflict within the Greens could not be resolved and in short time it led to depletion of the party’s membership base. Similar problems were encountered by the Czech Greens, which lost 1/3 of their members after ideological move towards the political left before the 2006 election or the Hungarian LMP which had split during its first term in parliament due to different stances on coalition strategy. Therefore, the Polish Greens did not escape the development trap that almost all CEE Green parties went through: internal party conflicts and tensions between the Green parties and environmental movement regarding the ideological profile of the party, which were strong also in Czech Republic (Fagan 2004) and Slovakia (Podoba 1998). This limited their rootedness in social groups, referring back to indicators proposed by Rose and Mackie (1988), which could foster party institutionalisation.

The conflict on abortion within a party resulted also in a loss of widely known environmental activists, whose popularity could be turned into a greater recognition of the party. Theories of party institutionalisation bring no clear answer on whether charismatics leader are beneficial for the process of party institutionalisation. Charisma, according to Panebianco (1988), may be interpreted as the opposite of institutionalisation: when the leader, and not the shared values, is the reference point for the party members, the routinisation of behaviour, including regular leadership changes, is harder to achieve and parties risk to fail when the leader departs. On the other hand, the charismatic leader, especially in the early stage of party formation, allows for more efficient mobilization of members and supporters, attracting media attention and improving social recognisability of the party. The studies by Bolleyer and Bytzek (2013) proved that new parties founded by individual entrepreneurs are less likely to achieve stability than new parties relying on ties to some social groups. However, due to their bottom-up genesis as well as programmatic emphasis on internal democracy and inclusive decision-making, the Green parties might be relatively resistant to the threat of personalization stemming from the leader’s charisma. Cases of successful Green parties from the region suggest that appointing a popular leader or joining the party by well-known public person (like Marek Strandberg in Estonian Green Party and Martin Bursík in Czech Green Party) has a fast beneficial effect on its visibility and, consequently, a better result in the election.

In the subsequent stages of party institutionalisation, initial ideology-based conflicts also translated into a strong emphasis on ideological purity. While the Baltic Green parties usually accepted on their electoral lists a wide spectrum of candidates presenting a variety of ideological options (Valentavicius 2017), the members of the Polish Greens and the candidates issued on their electoral lists were required to fully accept the party ideological stance. It also made it difficult to expand the number of members of the party. In turn, this hindered the routisation of behaviours in the party as permanent shortages of activists required special rules dependent on local situation. Regarding the external institutionalisation, small membership limited social recognition of the party and repertoire and frequency of its actions—the Greens remained the ‘sofa party’, concentrated in few largest urban centres.

By combining environmentalism with radical left-wing socio-cultural policies and prosocial economic stance, The Polish Greens had crosscut the existing political cleavage and found themselves in a political position that was very hard to exploit. Although the environmental movement in Poland had an anti-communist origin, the range of reasonable coalition partners of the Greens was restricted to the post-communist party due to the anti-abortion and anti-gay rights stance of the major post-Solidarity parties. Researching Polish political environmentalism in the early 2000s, Ferry (2002, pp. 174–175) noted that ‘for older activists, Solidarity’s overthrow of the communist party-state had been a defining moment in the development of the Polish Greens (…) and co-operation with ex-communists was still rejected.’ At the same time, the West-inspired combination of environmentalism, feminism and LGBT rights ideology established the Polish Greens as an ideological enemy of nearly whole post-Solidarity opposition.

Therefore, the party left-libertarian ideological choice greatly limited coalition possibilities. While the majority of Green parties in Central and Eastern Europe have been entering electoral or governmental coalitions mostly with the centre and right-wing parties, Polish Greens opportunities were limited to the post-communist left (SLD) and its splinters. However, because the Greens were formed as a critical reaction to ineffective and opportunistic rule of the post-communist party, a large proportion of Green party members and voters had a reluctant stance towards coalition with SLD, especially in the first years after party formation. Even though the coalition with SLD in 2010 local government election gave five seats for the Greens, many members of the Greens still perceived that agreement negatively.

The ideological choice of the Polish Greens greatly restricted their electoral base as well. As the 2008 survey has shown, perception of environmental protection as an important political issue was most popular among economically liberal people, interested in lowering taxes and reducing the role of trade unions. Social group with the greatest support for radical socio-cultural reforms, such as the legalization of same-sex partnerships, quota systems aimed at enhancement the percentage of women in the parliament and restoration of admissibility of abortion, also proved to be economically liberal, and not interested in environmentalism. At the same time, pro-environmental and economically pro-social people were characterized by higher traditionalism and conservatism, which was expressed primarily in the opposition to the legalization of same-sex relationships and abortion. This distribution of opinions ‘proved problematic to isolate acceptance for all three main elements of Green identity: a pro-environmental attitude, liberalism as far as worldviews are concerned and socialism in the area of economy’ (Sadura and Kwiatkowska 2008) and that, in turn, significantly limits the chances of a ‘red-green’ environmental party in Poland.

However, refereeing to durability (Rose and Mackie 1988; Janda 1980; Harmel et al. 2018) as a dimension of institutionalisation, the strong emphasis on Green values and ideological purity became the most important resource of the party (Kwiatkowska 2019). It allowed the Greens to endure for 15 years, surviving many internal and external crises, including long-term lack of parliamentary representation, ideological splits, and motivate them to keep engaging in political activities despite very limited resources. In the absence of material goods, which could be used to reward the party members, very high identification of the members with party ideology, values and methods of operation became the most important selective good (cf. Panebianco 1988, p. 54).

Affiliation to the European Green Party increased the external institutionalisation of the Green Party in Poland without acquiring a large number of voters. Since the party foundation, thanks to endorsements from the key EGP politicians, the Greens has attracted attention of media and other political parties far exceeding their electoral support. Their radical left-wing program also provided an incentive for more ideologically blurred parties to attract new groups of voters. Despite their very limited electoral support, Polish Greens participated, mostly as a minor partner in a centre or centre-left pre-election coalition, in all national elections except presidential ones, including elections to European Parliament (2004, 2009, 2014), national parliament (2005, 2007, 2011, 2015), and to local government (2006, 2010, 2014, 2018). Subsequently, acquiring regular public funding, which has become the source of the Greens’ financial resilience since 2005, allowed them to wait out worse times, waiting for increase of salience of environmental issues among Polish society.

6 Conclusions

Despite severe degradation of the natural environment in Central and Eastern European countries under the communist rule and its large mobilizing potential in the 1990s, only in a few of the Green parties rose to long-term relevance for the political system. Analysis of the political environment of the Green parties in Central and Eastern Europe has revealed limited possibilities of introducing environmentalism—in the form it emerged in the Western European countries—into the mainstream of political competition. The barriers identified at the level of voters’ preferences included: unmet material needs of a large part of the population, strong position of agricultural and industrial sectors in the employment structure, the lack of a large middle class forming a core social base of Green parties, strong conservatism and low salience of environmentalism as a political issue. These economic, social and political legacies of the communist regimes caused nearly all successful Green parties in the region to choose more centrist (Czech Republic) or right-wing (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) approach.

Besides programmatic self-positioning, the successes of the CEE Green parties can be explained primarily as effective arrangement of an ideologically wide model of the protest party and—in case of the Baltic Greens—the political power of local entrepreneurs (Sikk and Andersen 2009, pp. 352–364; Navickas 2017, p. 107), since environmentalism itself in the CEE is still insufficient to secure a political victory. Thanks to a broad, heterogeneous ideological base, they were able to take over the voters disillusioned with old political parties. Positioning of the parties close to the centre of the local political scene and lack of ideological rigidness translated also into openness to pre-electoral coalitions. The left-libertarian formula of the Polish Greens, the closest to the German Greens among the parties in the region, was too ideologically narrow to play as a catch-all protest party.

The Polish Green party was a late new-comer into the political system, and, despite high expectations, was unable to colonize the space left after the post-communist party’s gradual demise. The ideological choice of Polish Greens, inspired by close relation with German Greens, made them an ideological exception, closest among the CEE Green parties to the left-libertarian model dominating in the Western Europe, and resulted in their irregular, selective institutionalisation. Positioning across the political cleavage brought internal conflicts between the activists of the environmental and feminist movements, which reduced the number of party members and made acquiring new members more difficult. Extra-parliamentary origins resulted in lack of wide-known party leaders, which limited the media coverage and access to other resources.

On the other hand, ideological rigidity made the party highly valued by its members and this contributed to its high resilience towards internal and external shocks. Regardless of the lack of electoral success and no material benefits stemming from the membership, the party managed to conduct stable political activity, taking part in nearly all national and local elections. The surprisingly strong institutionalisation of the Greens can be seen also on the political level, due to their external source of legitimacy. Their affiliation to international political Green network allowed them to influence the strategies of other political actors disproportionately stronger than their electoral support would suggest. In turn, such external institutionalisation without voters and participation in pre-election coalitions provided them with a constant flow of funds without which they would not survive.

If successful institutionalisation in some dimensions may compensate for under-institutionalisation of others (Levitsky 1998) and there is no straight relationship between institutionalisation and political success (Bolleyer and Bytzek 2013), we may recognize adaptability and durability of a party as a sufficient condition for institutionalisation, especially in periods when political conditions are unfavourable. Time is working in favour of Green politics in Poland. The increasing levels of education and income, urbanisation, and growth of the service sector at the expense of agriculture and industry are supposed to bring about a cultural shift correlated with increased support for the post-materialist politics (Inglehart 1997; Kitschelt 1992). Progressing climate change might also bring environmentalism to the spotlight. Equally strong influences have been coming from the successes of Western European Green parties and the implementation of the European Union’s Community acquis into Polish law, both of which reshaped the perception of these issues from radical or valueless and promoted them to the main party competition space.

References

Abramson, Paul R., and Ronald Inglehart. 1995. Value change in global perspective. Ann Arbor: Michigan University Press.

Agarin, Timofey. 2009. Where have all the environmentalists gone? Baltic Greens in the mid-1990s. Journal of Baltic Studies 40(3):285–305.

Bakker, Ryan, Seth Jolly, and Polk Jonathan. 2012. Complexity in the European party space: exploring dimensionality with experts. European Union Politics 13(2):219–245.

Bakker, Ryan, Catherine de Vries, Erica Edwards, Liesbet Hooghe, Seth Jolly, Gary Marks, Jonathan Polk, Jan Rovny, Marco Steenbergen, and Milada Vachudova. 2015. Measuring party positions in Europe: The Chapel Hill expert survey trend file, 1999–2010. Party Politics 21(1):143–152.

Basedau, Matthias, and Alexander Stroh. 2008. Measuring party institutionalization in developing countries: a new research instrument applied to 28 African political parties. Giga Working Papers 69:3–27.

Bolleyer, Nicole, and Evelyn Bytzek. 2013. Origins of party formation and new party success in advanced democracies. European Journal for Political Research 52:773–796.

Bomberg, Elizabeth. 1998. Green parties and politics in European Union. London: Routledge.

Cordell, Karl, and Zdeněk Hausvater. 2006. Working together: the partnership between the Czech and German Greens as a model for wider Czech-German co-operation? Debatte 14(1):49–69.

Duverger, Maurice. 1963. Political parties. Their organization and activity in the modern state. London: Methuen & Co.

Ekiert, Grzegorz, and Stephen E. Hanson. 2003. Capitalism and democracy in Central and Eastern Europe: assessing the legacy of communist rule. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fagan, Adam. 2004. Environment and democracy in the Czech republic. The environmental movement in the transition process. Cheltenham, Northampton: Edward Elgar.

Ferry, Martin. 2002. The Polish Green movement ten years after the fall of communism. Environmental Politics 11(1):172–177.

Frankland, E. Gene. 2016. Central and Eastern European Green parties: rise, fall and revival? In Green parties in Europe, ed. Emilie Van Haute, 59–92. London: Routledge.

Fábián, Katalin. 2010. Can politics be different? The Hungarian Green Party’s entry into parliament in 2010. Environmental Politics 19(6):1006–1011.

Galbreath, David J., and Daunis Auers. 2009. Green, black and brown: uncovering Latvia’s environmental politics. Journal of Baltic Studies 40:333–348.

Gliński, Piotr. 1996. Polscy Zieloni. Ruch społeczny w okresie przemian. Warszawa: IFiS PAN.

Grabowska, Mirosława. 2005. Podział postkomunistyczny. Społeczne podstawy polityki w Polsce po 1989 roku. Warszawa: Scholar.

Grant, Zack P., and James Tilley. 2019. Fertile soil: explaining variation in the success of Green parties. West European Politics 42(3):495–516.

Grzymała-Busse, Anna. 2002. Redeeming the communist past: the regeneration of communist parties in east central europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harmel, Robert, and Kenneth Janda. 2004. An integrated theory of party goals and party change. Journal of Theoretical Politics 6:259–287.

Harmel, Robert, and John D. Robertson. 1985. Formation and success of new parties: a cross-national analysis. International Political Science Review 6(4):501–523.

Harmel, Robert, and Lars Svåsand (eds.). 2019. Institutionalisation of political parties. Comparative cases. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

Harmel, Robert, Lars Svåsand, and Mjelde Hilmar. 2018. Institutionalisation (and de-Institutionalisation) of right-wing protest parties. The progress parties in Denmark and Norway. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

Hicks, Barbara. 1996. Environmental politics in Poland: A social movement between regime and opposition. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hrynkiewicz, Józefina. 1990. Zieloni. Studia nad ruchem ekologicznym w Polsce 1980–1989. Warszawa: IS UW.

Huntington, Samuel. 1968. Political order in changing societies. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ibenskas, Raimondas, and Allan Sikk. 2017. Patterns of party change in Central and Eastern Europe, 1990–2015. Party Politics 23(1):43–54.

Inglehart, Ronald. 1997. Modernization and postmodernization: Cultural, economic, and political change in 43 societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Inglehart, Ronald, and Renata Siemienska. 1988. Changing values and political dissatisfaction in Poland and the west: a comparative analysis. Government and Opposition 23(4):440–457.

Janda, Kenneth. 1980. Political parties: a cross-national survey. New York: The Free Press.

Jehlička, Petr, and Tomáš Kostelecký. 1995. Czechoslovakia. Greens in a post-communist society. In The green challenge. The development of Green parties in Europe, ed. Dick Richardson, Chris Rootes, 208–231. London: Routledge.

Jehlička, Petr, Tomáš Kostelecký, and Daniel Kunštát. 2011. Czech Green politics after two decades: the May 2010 general election. Environmental Politics 20(3):418–425.

Kitschelt, Herbert. 1989. The logics of party formation: ecological politics in Belgium and west Germany. London: Cornell University Press.

Kitschelt, Herbert. 1992. The formation of party systems in East Central Europe. Politics and Society 20(1):7–50.

Kopeček, Lubomir. 2009. The Slovak Greens: a complex story of a small party. Communist and Post-communist Studies 42(1):115–140.

Kwiatkowska, Agnieszka. 2019. The uneven institutionalization of the Green Party in Poland. In Institutionalisation of political parties: comparative cases, ed. Robert Harmel, Lars Svasand, 133–154. New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

Levitsky, Steven. 1998. Institutionalization and Peronism. The concept, the case and the case for unpacking the concept. Party Politics 4(1):77–92.

Mainwaring, Scott, and Timothy Scully. 1995. Building democratic institutions: party systems in Latin America. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Maor, Moshe. 1997. Political parties and party systems: comparative approaches and the British experience. London: Routledge.

Marks, Gary, Lisbeth Hooghe, Moira Nelson, and Erica Edwards. 2006. Party competition and European integration in east and west. Different structure, same causality. Comparative Political Studies 39(2):155–175.

Meleshevich, Andrey. 2007. Party systems in post-soviet countries. A comparative study of political institutionalization in the Baltic States, Russia, and Ukraine. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Müller-Rommel, Ferdinand. 1989. New politics in Western Europe. The rise and success of Green parties and alternative lists. San Francisco, London: Westview Press.

Navickas, Andrius. 2017. Lithuania after politics? Political Preferences 14:99–114.

Panebianco, Angelo. 1988. Political parties: organization and power. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Podoba, Juraj. 1998. Rejecting Green velvet: transition, environment and nationalism in Slovakia. Environmental Politics 7(1):129–144.

Poguntke, Thomas. 1993. Alternative politics. The German Green Party. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Poguntke, Thomas, Susan Scarrow, and Paul Webb (eds.). 2016. Organizing political parties. Representation, participation, and power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Polk, Jonathan, Jan Rovny, Ryan Bakker, Erica Edwards, Liesbet Hooghe, Seth Jolly, Jelle Koedam, Filip Kostelka, Gary Marks, Gijs Schumacher, Marco Steenbergen, Milada Vachudova, and Marko Zilovic. 2017. Explaining the salience of anti-elitism and reducing political corruption for political parties in Europe with the 2014 Chapel Hill Expert Survey data. Research & Politics 4(1):205316801668691. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168016686915.

Randall, Vicky, and Lars Svåsand. 2002. Party institutionalization in new democracies. Party Politics 8(1):5–29.

Rose, Richard, and Thomas Mackie. 1988. Do parties persist or fail? The big trade-off facing organizations. In When parties fail, ed. Kay Lawson, Peter Merkl, 533–558. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rovny, Jan, and Edwards Erica. 2012. Struggle over dimensionality. Party competition in Western and Eastern Europe. East European Politics & Societies 26(1):56–74.

Sadura, Przemysław, and Agnieszka Kwiatkowska. 2008. Green politics in a post-political society. In Polish shades of green: Green ideas and political powers in Poland, ed. Przemysław Sadura, 6–10. Brussels, Warsaw: HBS.

Sikk, Allan, and Rune H. Andersen. 2009. Without a tinge of red: the fall and rise of the Estonian Greens. Journal of Baltic Studies 40(3):349–373.

Staniszkis, Jadwiga. 1991. The dynamics of the breakthrough in Eastern Europe. The Polish experience. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Tickle, Andrew, and Ian Welsh (eds.). 1998. Environment and society in Eastern Europe. Essex: Longman.

Valentinavicius, Virgis. 2017. Lithuanian election 2016: the mainstream left and right rejected by voters angry with the establishment. Political Preferences 14:19–34.

Waluszko, Janusz. 2013. Protesty przeciwko budowie elektrowni jądrowej Żarnowiec w latach 1985–1990. Gdańsk: IPN.

Weissenbach, Kristina. 2010. Political party assistance in transition: the German ‘Stiftungen’ in sub-Saharan Africa. Democratization 17(6):1225–1249.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kwiatkowska, A. Institutionalisation without voters: the Green Party in Poland in comparative perspective. Z Vgl Polit Wiss 13, 273–294 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-019-00424-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-019-00424-6