Abstract

Why have the third wave of democratisation and concurrent economic liberalisation, contrary to many expectations, failed to lower global corruption? This article comparatively assesses systemic corruption and other features of personal rule in Argentina, Venezuela, Indonesia, the Philippines, Kenya, and Zambia. It finds that systemic corruption in these countries persists despite political transitions and economic liberalisation, and that democratisation as the most important factor has not been “deep” enough to decisively influence the level of corruption. Moreover, systemic corruption does not work in isolation but goes hand-in-hand with clientelism, another feature of personal rule.

Zusammenfassung

Warum haben die dritte Welle der Demokratisierung und die damit einhergehende ökonomische Liberalisierung, im Gegensatz zu den Erwartungen vieler, nicht zu nicht zu einem geringeren Ausmaß von Korruption geführt? Der vorliegende Aufsatz untersucht aus vergleichender Perspektive systemische Korruption und weitere Eigenschaften personalisierter Herrschaft in Argentinien, Venezuela, Indonesien, den Philippinen, Kenia und Sambia. Der Artikel kommt zu dem Schluss, dass systemische Korruption in diesen Ländern trotz politischer Transition und ökonomischer Liberalisierung fortbesteht und dass Demokratisierung als wichtigster Einflussfaktor nicht tief genug greift, um das Ausmaß von Korruption nachhaltig zu beeinflussen. Systemische Korruption geht zudem einher mit Klientelismus, einem weiteren Wesensmerkmal personalisierter Herrschaft.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Other indices include the Corruption Perceptions Index (Transparency International), the Country Policy and Institution Assessment, CPIA (World Bank); the International Country Risk Guide, ICRG; the Global Integrity Index; and the Bertelsmann Transformation Index. For a critical voice on these indices, see Sindzingre/Milelli (2010).

This follows Geddes’ conceptualisation (1999, p. 116, fn. 1): “I counted an authoritarian regime as defunct if either the dictator and his supporters had been ousted from office or if a negotiated transition resulted in reasonably fair, competitive elections and a change in the party or individual occupying executive office.”

Cf. also the five building blocks of the Fraser Institute’s annual Economic Freedom in the World Index (Gwartney u. a. 2011). Those reflecting the three elements of economic liberalisation referred to above are (1) the regulation of credit, labour, and business; (2) the freedom to trade internationally; and (3) the size of the government.

This operationalisation, however, is fraught with problems, as it could also measure statehood. Here it is only taken as an indication for potential correlation. Montinola and Jackman also find that corruption is pervasive in low-income economies.

A different definition to the same effect was coined by Klitgaard (1997, p. 500–501): “Corruption equals monopoly plus discretion minus accountability”.

North (1990, p. 3), in his much-cited notion, defined institutions as “the rules of the game in a society or, more formally, […] the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction.” Hence, this article is not concerned with individual forms of political and bureaucratic corruption, which can be found in every society and polity.

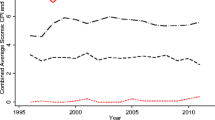

The scores are meant to provide a general overview of the six countries’ democratic features as assessed by Freedom House. Freedom House was selected for want of better alternatives capturing the same features (for critical assessments of indices assessing democracy and the rule of law, see Munck 2009; Skaaning 2010). Unfortunately, the “internal consistency of the data series is open to question” due to changes in methodology and coding (Munck and Verkuilen 2002, p. 21, fn. 13). Furthermore, Freedom House only provides the detailed break-down of subcategories from 2006 to today. Hence, it is not possible to follow up the long-term dynamics of these subcategories for a longer period and to compare scores over time. This would provide further information on the long-term effects of particular democratic features such as freedom of expression and belief. Furthermore, subcategory C “functioning of government” contains measures of corruption (Corruption Perceptions Index from Transparency International), so it is not disjunctive from the dependent variable. In the analysis, reference will be made to the other subcategories only.

Comparative data for these different features of neopatrimonialism were collected and calculated for the research project “Persistence and change of neopatrimonialism in various Non-OECD regions”, input from Nina Korte and Karsten Bechle is acknowledged. Cf. also von Soest et al. (2011).

The CPI and the Worldwide Governance Indicators assess multiple phenomena, e.g. both political and bureaucratic corruption. Both incorporate various studies in which experts give their perception on a country’s incidence of corruption. As most of these focus on the perspective of business, political corruption is underestimated (cf. Pech 2009, p. 8; Johnston 2005). In consequence, precise ranking of countries according to their corruption seems futile. However, as of now, only perception-based indicators of corruption have a world-wide coverage; attempts to empirically capture respondents’ personal experiences with corruption are only emerging and focus on specific countries or world regions (cf. Afrobarometer, for an example see Bratton 2007).

The analysis draws on the case studies carried out for the research project “Persistence and Change of Neopatrimonialism in Various Non-OECD Regions”. Field research in Argentina and Venezuela was conducted by Karsten Bechle, in the Philippines and Indonesia by Nina Korte and in Kenya and Zambia by Christian von Soest. Cf. also von Soest et al. (2011).

For a detailed analysis of Indonesia’s income structure and governance mechanisms cf. Korte (2011).

In August 2011, the KACC was disbanded and replaced by the “Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission”. Its new head was only appointed in May 2012 (Reuters 2012).

This finding would still contrast Rock’s (2009) result that a positive corruption effect on average is visible 10–12 years after a democratic transition.

References

Ades, Alberto, and Rafael Di Tella. 1997. The new economics of corruption: A survey and some new results. Political Studies 45 (3): 496–515.

Ades, Alberto, and Rafael Di Tella. 1999. Rents, competition, and corruption. American Economic Review 89:982–993.

Anders, Gerhard. 2002. Like chameleons. Civil servants and corruption in Malawi. Bulletin de l’APAD 23–24. http://apad.revues.org/137. Accessed 17 April 2013.

Anderson, Christopher J., and Yuliya V. Tverdova. 2003. Corruption, political allegiances, and attitudes toward government in contemporary democracies. American Journal of Political Science 47 (1): 91–109.

Anderson, David, and Emma Lochery. 2008. Violence and exodus in Kenya’s rift valley, 2008: Predictable and preventable? Journal of Eastern African Studies 2 (2): 328–343.

Andreassen, Bård-Anders, Gisela Geisler, and Arne Tostensen. 1992. Setting a standard for Africa? Lessons from the 1991 Zambian elections. CMI report (5). Bergen: Christian Michelsen Institute.

Andvig, Jens Christian, Odd-Helge Fjeldstad, Inge Amundsen, Tone Sissner, and Tina Søreide. 2001. Corruption—a review of contemporary research. CMI report (7). Bergen: Christian Michelsen Institute.

Bach, Daniel. 2011. Patrimonialism and neopatrimonialism: Comparative trajectories and readings. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 49 (3): 275–294.

Bach, Daniel, and Mamoudou Gazibo, eds. 2011. Neopatrimonialism in Africa and beyond. London: Routledge.

Bäck, Hanna, and Axel Hadenius. 2008. Democracy and state capacity: Exploring a J-shaped relationship. Governance 21 (1): 1–24.

Banks, Arthur S. 2011. Cross-national time series data archive. http://www.databanksinternational.com. Accessed 1 Feb 2011.

Basedau, Matthias. 2003. Erfolgsbedingungen von Demokratie im subsaharischen Afrika. Opladen: Leske und Budrich.

Bates, Robert H., Avner Greif, Margaret Levi, Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, and Barry R. Weingast. 1998. Analytic narratives. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Blundo, Giorgia, and Jean-Pierre Olivier de Sardan. 2006. Everyday Corruption and the State: Citizens and Public Officials in Africa. London: Zed Books.

Bogaards, Matthijs. 2009. How to classify hybrid regimes? Defective democracy and electoral authoritarianism. Democratization 16:399–423.

Bratton, Michael. 1992. Zambia starts over. Journal of Democracy 3 (2): 81–94.

Bratton, Michael. 2007. Formal versus informal institutions in Africa. Journal of Democracy18 (3): 96–110.

Bratton, Michael, and Nicholas van de Walle. 1997. Democratic experiments in Africa. Regime transitions in comparative perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brinkerhoff, Derick W., and Arthur A. Goldsmith. 2002. Clientelism, patrimonialism and democratic governance: An overview and framework for assessment and programming. Report prepared for U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), Office of democracy and governance.

Carothers, Thomas. 2002. The end of the transition paradigm. Journal of Democracy 13 (1): 5–21.

Charron, Nicholas, and Victor Lapuente. 2010. Does democracy produce quality of government? European Journal of Political Research 49 (4): 443–470.

Cheeseman, Nic. 2008. The Kenyan elections of 2007: An introduction. Journal of Eastern African Studies 2 (2): 166–184.

Corrales, Javier. 2002. Presidents without parties: The politics of economic reform in Argentina and Venezuela in the 1990s. University Park: Penn State University Press.

Craig, John. 2001. Putting privatisation into practice: The case of Zambia consolidated copper mines limited. Journal of Modern African Studies 39 (3): 389–410.

Croissant, Aurel. 2002. Von der Transition zur defekten Demokratie. Demokratische Entwicklungen in den Philippinen, Südkorea und Thailand. Wiesbaden: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Crouch, Harold. 1979. Patrimonialism and military rule in Indonesia. World Politics 31 (3): 571–587.

Dahl, Robert A. 1971. Polyarchy: Participation and opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Daloz, Jean-Pascal. 2003. ‘Big Men’ in sub-saharan Africa: How elites accumulate positions and resources. Comparative Sociology 2 (1): 271–285.

deGrassi, Aaron. 2008. ‘Neopatrimonialism’ and agricultural development in Africa: Contributions and limitations of a contested concept. African Studies Review 51 (3): 107–133.

Della Porta, Donatella, and Alberto Vannucci. 1999. Corrupt exchanges: Actors, resources, and mechanisms of political corruption. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Diepeveen, Stephanie. 2010. ‘The Kenyas we don’t want’: Popular thought over constitutional review in Kenya, 2002. The Journal of Modern African Studies 48 (2): 231–258.

Doig, Alan, and Robin Theobald. 2000. Corruption and democratisation. Oxford: Routledge.

Erdmann, Gero, and Ulf Engel. 2007. Neopatrimonialism reconsidered: Critical review and elaboration of an elusive concept. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 45 (1): 95–119.

Färdigh, Mathias, Emma Andersson, and Henrik Oscarsson. 2011. Reexaming the relationship between press freedom and corruption. QOG Working Paper (13), Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg, Quality of Government Institute. http://www.qog.pol.gu.se. Accessed 21 Nov 2011.

Ferraz, João Carlos, David Kupfer, and Mariana Iootty. 2003. Made in Brazil: Industrial competitiveness ten years after economic liberalisation. A study on the impact of economic liberalization in Brazil: 1995–2002. Latin America Studies Series. Rio de Janeiro: Japan External TradeOrganization, Institute of Developing Economies.

Fraser, Alastair, and John Lungu. 2007. For whom the windfalls? Winners and losers in the privatisation of Zambia’s copper mines. Lusaka: Civil Society Trade Network of Zambia (CSTNZ)/Catholic Centre for Justice, Peace and Development (CCJPD).

Freedom House. 2007. Freedom in the world 2007: The annual survey of political rights and civil liberties. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Freedom House. 2011. Freedom in the World 2010. Data and country reports from freedom house’s annual global survey of political rights and civil liberties. http://www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=15. Accessed 1 Sept 2011.

Frye, Timothy, and Andrei Shleifer. 1997. The invisible hand and the grabbing hand. American Economic Review 87 (2): 354–58.

Geddes, Barbara. 1999. What do we know about democratization after twenty years? Annual Review of Political Science 2:115–144.

Gerring, John. 2007. Case study research: Principles and practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gerring, John, and Strom C. Thacker. 2004. Political institutions and corruption: The role of unitarism and parliamentarism. British Journal of Political Science 34 (2): 295–330.

Githongo, John. 2008. Kenya—riding the tiger. Journal of Eastern African Studies 2 (2): 359–367.

Goel, Rajeev K, and Michael A Nelson. 2005. Economic freedom versus political freedom: Cross-country influences on corruption. Australian Economic Papers 44 (2): 121–133.

Goertz, Gary. 2005. Social science concepts: A user’s guide. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Goertz, Gary, and Harvey Starr. 2001. Introduction: Necessary condition logics, research design, and theory. In Necessary conditions: Theory, methodology, and applications, eds. Gary Goertz and Harvey Starr, 1–23, Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Gordin, Jorge P. 2002. The Political and partisan determinants of patronage in Latin America 1960–1994. A comparative perspective. European Journal of Political Research 41 (4): 513–549.

Guliyev, Farid. 2011. Personal rule, neopatrimonialism, and regime typologies: Integrating Dahlian and Weberian approaches to regime studies. Democratization 18:575–601.

Gwartney, James D., Robert Lawson, and Joshua C. Hall. 2011. Economic freedom of the world: 2011 Annual report. Calgary: Fraser Institute. http://www.freetheworld.com. Accessed 12 Oct 2011.

Harris-White, Barbara, and Gordon White. 1996. Corruption, liberalization and democracy: Editorial introduction. IDS Bulletin 27 (2): 1–5.

Heidenheimer, Arnold J., and Michael Johnston. 2002. Introduction to part I. In Political corruption—concepts and contexts, eds. Arnold J. Heidenheimer and Michael Johnston, 3–14. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Hellman, Joel S., Geraint Jones, and Daniel Kaufmann. 2000. ‘Seize the state, seize the day’: State capture, corruption and influence in transition. Policy Research Working Paper (2444). Washington: World Bank.

Herzfeld, Thomas and Christoph Weiss. 2003. Corruption and legal (in)effectiveness: An empirical investigation. European Journal of Political Economy 19 (3): 621–632.

Homi, Katrak. 2002. Does economic liberalisation endanger indigenous technological developments?: An analysis of the Indian experience. Research Policy 31 (1): 19–30.

Hutchcroft, Paul D. 2008. The arroyo imbroglio in the Philippines. Journal of Democracy19 (1): 141–155.

Hutchcroft, Paul D., and Joel Rocamora. 2003. Strong demands and weak institutions: The origins and evolution of the democratic deficit in the Philippines. Journal of East Asian Studies 3:259–292.

Jellinek, Georg. 1959/1900. Allgemeine Staatslehre. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Johnston, Michael. 2005. Syndromes of corruption. Wealth, power, and democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Karl, Terry Lynn. 1995. The hybrid regimes of central America. Journal of Democracy 6:72–86.

Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2009. Governance matters VIII: Aggregate and individual governance indicators for 1996–2008. Washington: World Bank.

Kaufmann, Daniel, Aart Kraay, and Massimo Mastruzzi. 2010. The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues. Washington: World Bank.

Keefer, Philip. 2007. Clientelism, credibility, and the policy choices of young democracies. American Journal of Political Science 51 (4): 804–821.

Kitschelt, Herbert, and Steven I. Wilkinson. 2007. Citizen-politician Linkages: An introduction. In Patrons, clients and policies. Patterns of democratic accountability and political competition, eds. Herbert Kitschelt and Steven I. Wilkinson, 1–49. Cambridge University Press.

Klitgaard, Robert. 1997. Cleaning up and invigorating the civil service. Public Administration and Development 17 (5): 487–509.

Kneip, Sascha. 2011. Constitutional courts as democratic actors and promoters of the rule of law: Institutional prerequisites and normative foundations. Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 5:131–155.

Korte, Nina. 2011. It’s not only rents: Explaining the persistence and change of neopatrimonialism in Indonesia. GIGA Working Paper (167). Hamburg: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies.

Krueger, Anne O. 1974. The political economy of the rent-seeking society. American Economic Review 64 (3): 291–303.

Lambsdorff, Johann Graf. 2007. The institutional economics of corruption and reform: Theory, evidence, and policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Larmer, Miles. 2005. Reaction and resistance to neo-liberalism in Zambia. Review of African Political Economy 32 (103): 29–45.

Larmer, Miles. 2009. Zambia since 1990: Paradoxes of democratic transition. In Turning points in African democracy, eds. Abdul Raufu Mustapha and Lindsay Whitfield, 114–133. Woodbridge: James Currey.

Latinobarómetro. 2008. Latinobarómetro, Informe 2008. Santiago de Chile: Corporación Latinobarómetro.

Lederman, Daniel, Norman Loayza, and Rodrigo Reis Soares. 2005. Accountability and corruption: Political institutions matter. Economics and Politics 17 (1): 1–35.

Lindberg, Staffan I. 2003. “It’s our time to ‘Chop’ ”: Do elections in Africa feed neo-patrimonialism rather than counteract it? Democratization 10 (2): 121–140.

Lindberg, Staffan I. 2010. What accountability pressures do MPs in Africa face and how do they respond? Evidence from Ghana. Journal of Modern African Studies 48 (1): 117–142.

Linz, Juan J. 1990. The perils of presidentialism. Journal of Democracy 1 (1): 51–69.

Llamazares, Iván. 2005. Patterns in contingencies: The interlocking of formal and informal institutions in contemporary Argentina. Social Forces 83 (4): 1671–1696.

Llanos, Mariana. 2001. Understanding presidential power in Argentina: A study of the policy of privatisation in the 1990s. Journal of Latin American Studies 33:67–99.

Mähler, Annegret. 2011. Oil in Venezuela: Triggering conflicts or ensuring stability? A historical comparative analysis. Politics & Policy 39 (4): 583–611.

Manow, Philip. 2002. Was erklärt politische Patronage in den Ländern Westeuropas? Defizite des politischen Wettbewerbs oder historisch-formative Phasen der Massendemokratisierung. Politische Vierteljahresschrift 43 (1): 20–45.

McFerson, Hazel M. 2009. Governance and hyper-corruption in resource-rich African countries. Third World Quarterly 30 (8):1529–1547.

Merkel, Wolfgang. 2004. Embedded and defective democracies. Democratization 11 (5): 33–58.

Merkel, Wolfgang. 2010. Systemtransformation. Eine Einführung in die Theorie und Empirie der Transformationsforschung. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Merolla, Jennifer L., and Elizabeth J. Zechmeister. 2011. The nature, determinants, and consequences of Chávez’s Charisma: Evidence from a study of Venezuelan public opinion. Comparative Political Studies 44 (28): 28–54.

Montinola, Gabriella R., and Robert W. Jackman. 2002. Sources of corruption: A cross-country study. British Journal of Political Science 32 (1): 147–170.

Mueller, Susanne D. 2008. The political economy of Kenya’s crisis. Journal of Eastern African Studies 2 (2): 185–210.

Munck, Gerardo L. 2009. Measuring democracy: A bridge between scholarship and politics. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Munck, Gerardo L., and Jay Verkuilen. 2002. Conceptualizing and measuring democracy. Comparative Political Studies 35 (1): 5–34.

Mungiu-Pippidi, Alina. 2006. Corruption: Diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Democracy 17 (3): 86–99.

Mungiu-Pippidi, Alina. 2010. Civil society as an anticorruption actor. Some lessons learned from the east central European experience. Report. Berlin: Civil Society against Corruption/Romanian Academic Society. http://www.againstcorruption.eu. Accessed 2 Nov 2011.

NORAD. 2011. Contextual choices in fighting corruption: Lessons learned. Report 4/2011. Study. Oslo: Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), Evaluation Department.

North, Douglass C. 1990. Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

North, Douglass C., John J. Wallis, and Barry R. Weingast. 2009. Violence and social orders. A conceptual framework for interpreting recorded human history. New York: Cambridge University Press.

O’Donnell, Guillermo A., and Philippe C. Schmitter. 1986. Transitions from authoritarian rule: Tentative conclusions about uncertain democracies. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Paldam, Martin. 1999. The big pattern of corruption: Economics, culture and the seesaw dynamics. Economics Working Papers 11. Aarhus: University of Aarhus, School of Economics and Management.

Pech, Birgit. 2009. Korruption und Demokratisierung. Rekonstruktion des Forschungsstandes an den Schnittstellen zu Institutionenökonomik und Politischer Transformationsforschung. INEF-Report 99, Duisburg: Universität Duisburg-Essen, Institut für Entwicklung und Frieden (INEF).

Penfold-Becerra, Michael. 2007. Clientelism and social funds: Evidence from Chávez’s misiones. Latin American Politics & Society 49:63–84.

Piattoni, Simona. 2001. Clientelism, interests, and democratic representation. The European experience in historical and comparative perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pitcher, Anne, Mary H. Moran, and Michael Johnston. 2009. Rethinking patrimonialism and neopatrimonialism in Africa. African Studies Review 52 (1): 125–156.

Powell, John Duncan. 1970. Peasant societies and clientelist politics. American Political Science Review 64:411–425.

Przeworski, Adam, and Henry Teune. 1970. The logic of comparative social enquiry. Malabar: Krieger Publishing.

Ragin, Charles C. 1987. The comparative method. Moving beyond qualitative and quantitative strategies. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rakner, Lise. 2003. Political and economic liberalisation in Zambia 1991–2001. Uppsala: Nordic Africa Institute.

Reuters. 2012. Kenya approves new anti-corruption chief. Reuters Africa. http://af.reuters.com/article/kenyaNews/idAFL5E8GAHEQ20120510. Accessed 6 June 2012.

Rock, Michael T. 2009. Corruption and democracy. Journal of Development Studies 45:55–75.

Roniger, Luis. 2004. Political clientelism, democracy, and market economy. Comparative Politics 36 (3): 353–375.

Rose-Ackerman, Susan. 1978. Corruption: A study in political economy. New York: Academic Press.

Rose-Ackerman, Susan. 1999. Corruption and government: causes, consequences, and reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Roth, Guenther. 1968. Personal rulership, patrimonialism, and empire-building in new states. World Politics 20 (2): 194–206.

Rothstein, Bo, and Jan Teorell. 2008. What is quality of government? A theory of impartial government institutions. Governance 21 (2): 165–190.

Routledge. 2011. Africa south of the sahara. London: Taylor and Francis.

Schedler, Andreas, ed. 2006. Electoral authoritarianism: The dynamics of unfree competition. Boulder: Lynne Rienner.

Schemmel, Benjamin. 2011. Rulers. http://www.rulers.org. Accessed 29 Sept 2011.

Schmidt, Steffen W., Laura Guasti, Carl H. Landé, and James C. Scott. 1977. Friends, followers, and factions. A reader in political clientelism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Setiyono, Budi, and Ross H. McLeod. 2010. Civil society organisations’ contribution to the anti-corruption movement in Indonesia. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 46:347–370.

Simon, David J. 2005. Democracy unrealized. Zambia’s Third Republic under Frederick Chiluba. In The fate of Africa’s democratic experiments. Elites and institutions, eds. Leonard A. Villalón and Peter VonDoepp, 199–220. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Sindzingre, Alice N., and Christian Milelli. 2010. The uncertain relationship between corruption and growth in developing countries: Threshold effects and state effectiveness. EconomiX Working Papers 10. Nanterre: University of Paris West—Nanterre la Défense, EconomiX.

Skaaning, Svend-Erik. 2010. Measuring the rule of law. Political Research Quarterly 63 (2): 449–460.

Snyder, Richard. 1992. Explaining transitions from neopatrimonial dictatorships. Comparative Politics 24 (4): 379–400.

Snyder, Richard, and James Mahoney. 1999. The missing variable. Institutions and the study of regime change. Comparative Politics 32 (1): 103–122.

Steeves, Jeffrey. 2006. Presidential succession in Kenya: The transition from Moi to Kibaki. Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 44 (2): 211–233.

Stepan, Alfred, and Cindy Skach. 1993. Constitutional frameworks and democratic consolidation: Parliamentarism versus presidentialism. World Politics 46 (1): 1–22.

Sung, Hung-En. 2004. Democracy and political corruption: A cross-national comparison. Crime, Law and Social Change 41:179–193.

Thompson, Mark R. 1995. The anti-marcos struggle: Personalistic rule and democratic transition in the Philippines. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Throup, David, and Charles Hornsby. 1998. Multi-party politics in Kenya: The Kenyatta and Moi states and the triumph of the system in the 1992 Election. Oxford: James Currey.

Treisman, Daniel. 2000. The causes of corruption: A cross-national study. Journal of Public Economics 76 (3): 399–457.

Turner, Barry. 2011. Stateman’s yearbook. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Ufen, Andreas. 2006. Political parties in post-suharto Indonesia: dealiranisasi and ‘Philippinisation’. GIGA Working Paper 37. Hamburg: GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies.

van de Walle, Nicolas. 2003. Presidentialism and clientelism in Africa’s emerging party systems. Journal of Modern African Studies 41 (2): 297–321.

van de Walle, Nicolas. 2009. The democratization of political clientelism in sub-saharan Africa. Paper delivered at the 3rd European Conference on African Studies (AEGIS). Leipzig, 4–7 June 2009.

von Soest, Christian. 2009. The African state and its revenues. How politics influences tax collection in Zambia and Botswana. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

von Soest, Christian, Karsten Bechle, and Nina Korte. 2011. How neopatrimonialism affects tax administration: A comparative study of three world regions. Third World Quarterly 32 (7): 1307–1329.

Weber, Max. 1980/1922. Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Grundriß der Verstehenden Soziologie. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr.

Weghorst, Keith R., and Staffan I. Lindberg. 2011. Effective opposition strategies: Collective goods or clientelism? Democratization 18:1193–1214.

Widner, Jennifer A. 1992. The Rise of a party-state in Kenya: From “Harambee!” to “Nyayo!” Berkeley: University of California Press.

Williamson, John. 2000. What should the world bank think about the Washington consensus? World Bank Research Observer 15 (2): 251–264.

World Bank. 1997. World development report 1997: The state in a changing world. Washington: World Bank/Oxford University Press.

World Bank. 2011a. World development indicators. http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/world-development-indicators. Accessed 20 Oct 2011.

World Bank. 2011b. Worldwide governance indicators. http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi. Accessed 20 Oct 2011.

Wrong, Michela. 2009. It’s our turn to eat. The story of a Kenyan whistleblower. London: Fourth Estate.

Zagorski, Paul W. 2003. Democratic breakdown in Paraguay and Venezuela: The shape of things to come for Latin America? Armed Forces & Society 30 (1): 87–116.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This articles draws on results from the research project “Persistence and Change of Neopatrimonialism in Various Non-OECD Regions”, which was conducted from 2008 to 2011 at the GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies and was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG). Further collaborators in the project were Nina Korte and Karsten Bechle, who also conducted field research in Indonesia and the Philippines (Nina Korte) and Venezuela and Argentina (Karsten Bechle). The author also thanks Bert Hoffmann for helpful advice.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

von Soest, C. Persistent systemic corruption: why democratisation and economic liberalisation have failed to undo an old evil. Z Vgl Polit Wiss 7 (Suppl 1), 57–87 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-013-0157-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12286-013-0157-6