Abstract

The languages of Northeast Asia show evidence of dispersal from south to north, consistent with the hypothesis that agriculture spread north and east from the vicinity of Liaoning, beginning with the millets approximately 5500 BP. Wet rice agriculture in Korea and Japan results from a later spread, also beginning in Shandong, crossing via the Liaodong peninsula and reaching the Korean peninsula around 1500 BCE. This dispersal is associated with the Mumun archaeological culture after 1500 BCE in the Korean peninsula and the Yayoi culture after 950 BCE in the Japanese archipelago. From a linguistic standpoint, it is associated with the entry of the Japonic language family, first into the Korean peninsula, subsequently into the Japanese archipelago. The arrival of Koreanic is associated with the advent of the Korean-style bronze dagger culture and a temporary hiatus in wet rice agriculture sites around 300 BCE. Both Koreanic and Japonic are relatively shallow language families, with Koreanic the shallower of the two, consistent with the chronology above. The gap between the earliest linguistically motivated dates for these language families and the archaeological events is the result of a linguistic founders effect, providing further evidence for demic diffusion as a source for their distribution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This paper examines the relationship between the linguistic ecology of Northeast Asia and the spread of rice agriculture. It focuses on the subpart of the region where wet rice agriculture became established three and a half millenia ago, Korea and Japan. “Linguistic ecology” refers to the interactions between a language and its environment, including the languages spoken around it (Haugen 1972: 325). I argue that the historical distribution of the Japonic and Koreanic language families is associated with two events in the archaeological record. The distribution of Japonic, first on the Korean peninsula and later in the Japanese archipelago, results from the relatively rapid spread of wet rice agriculture down the Korean peninsula to its southern tip. Wet rice cultivation reaches northern Kyūshū by 950 BCE, and the western end of the Inland Sea by 600 BCE. The distribution of Koreanic, and ultimately, the disappearance of Japonic from the Korean peninsula, results from the arrival of a population which is associated with a temporary hiatus in wet rice agriculture in the southern Korean peninsula around 300 BCE.

The methodology of the paper is as follows. I first report what I take to be important points of consensus between archaeologists in Korea and Japan regarding the beginning of wet rice agriculture in the region and describe briefly what we know about the linguistic ecology of the Korean peninsula from the earliest Chinese sources. I then consider how three types of linguistic data can be reconciled with this information: historical data on the location of speakers of the languages, the dates of the protofamilies involved, and the nature of the vocabulary related to agriculture.

Background

As a linguistic area, Northeast Asia is made up of ten language families: Ainuic, Amuric (Nivkh/Gilyak), Japonic, Kamchukotic, Koreanic, Mongolic, Tungusic, Turkic, Yeniseic, and Yukaghiric (Janhunen 1998: 196–197). The distribution of these language families is shown in Fig. 1. The third, fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth of these families are sometimes related by various versions of the Altaic hypothesis, which asserts a genetic relation between Mongolic, Tungusic, and Turkic (Ramstedt 1952) or between these three families and Koreanic (Poppe 1960) and Japonic (Starostin et al. 2003; Robbeets 2005). However, there is still no scholarly consensus about the Altaic hypothesis; for critiques, see Georg et al. (1999) and Vovin (2005), among many others.Footnote 1

Food production in Northeast Asia ranges from wet rice cultivation in Korea and Japan to steppe pastoralism in Mongolic and Turkic language areas, to reindeer pastoralism among speakers of Kamchukotic, Yeniseic, Yukaghiric, and Tungusic, to hunting and fishing among these groups and Ainuic. Table 1 gives a basic correlation of language families, location, and primary modes of food production.

While Table 1 associates only Japonic and Koreanic with rice agriculture, historical, linguistic, and archaeological evidence indicates that dry field agriculture extended much further north in the region. Among the language families in Table 1, the Jurchens, the oldest clearly identifiable speakers of a Tungusic language, grew millet along with other crops (Franke 1990: 416). While traditional Chinese and Western historiography present “Altaic” (Tungusic, Mongolic, Turkic)-speaking populations as pastoralists or hunter/gathers originating from the north of contemporary Han Chinese-speaking regions, it is quite possible that the historical distribution of these language families results from the expansion of earlier agriculturalists from the south. Janhunen (1998: 202) points out that Tungusic as well as Amuric and Kamchukotic gives evidence for having expanded relatively recently into the northern part of its range. We know that Panicum (broomcorn) and Setaria (foxtail) millet are associated with the Zaisanovka culture in the Russian Primorye (Maritime) region as early as 4600 BP (Kuzmin 2008: 6), well to the north of the historical center of Tungusic. It is thus possible that Northeast Asian language groups not associated with agriculture in historical times were agriculturalists at earlier periods. Such a view would be consistent with the Shandong/Liaodong dispersion hypothesis presented in the next section.

Archaeological and historical considerations

The Shandong/Liaodong dispersion hypothesis

Miyamoto (2009) presents a scenario where agriculture spread from (possibly distinct) locations in northeast China to the east and north (Fig. 2). Miyamoto distinguishes three major spreads of agriculture from this region. The first, associated with Setaria and Panicum, spreads from the Liaoning region to the northwestern part of the Korean peninsula and thence to its eastern and southern coasts. Almost simultaneously, a spread of these cultivars took place from northeast China to the south of Primoriye and thence to its coastal plain (Miyamoto 2009: 25–6). Miyamoto dates this first spread to the first half of the fourth millennium BCE. The second dispersion adds dry field rice cultivation to the millets; it spreads from Shandong through the Liaodong peninsula to the south of the Korean peninsula in the second half of the third millennium BCE. The third dispersion includes wet rice cultivation and associated tool complexes. It takes the same route from Shandong to Liaodong to the Korean peninsula around the middle of the second millennium BCE. In the Korean peninsula, it is associated with the Mumun (plain, patternless) ceramic culture and irrigated paddy cultivation. This third dispersion reaches the Japanese archipelago, where wet rice cultivation appears in northern Kyūshū around 950 BCE (800 BCE according to Miyamoto 2009: 28).Footnote 2

The Shandong/Liaodong dispersion hypothesis, based on Miyamoto (2009: 26).

Miyamoto’s scenario for the third dispersion is consistent with the scenario for the introduction of wet rice cultivation into the Korean peninsula provided by Ahn (2010). Ahn discusses and dismisses claims for very early rice cultivation in the Korean peninsula and finds inconclusive evidence for rice cultivation during the Chŭlmun (comb pattern) period (ca. 6000–1300 BCE). Previous researchers (e.g., Crawford and Lee 2003) concur on the evidence for Chŭlmun cultivation of Setaria and Panicum diffused from the Liaoning region, consistent with the Shandong/Liaodong dispersion hypothesis. Ahn argues against earlier views that wet rice cultivation was introduced into the Korean peninsula from the south, and concludes in favor of the scenario where it enters the peninsula from Liaodong in the early Mumun period around or after 1500 BCE. Thereafter, evidence for agricultural settlements engaged in rice farming is found throughout the peninsula with the exception of the northeast. The relative importance of wet rice cultivation shows regional variation throughout the Mumun period: wet rice is dominant in the central and southwest regions, while millet and other dry field crops are relatively more important in the southeast (Ahn 2010: 93).

Hiatus in wet rice agriculture on the Korean peninsula

According to Ahn (2003: 81–81; 2010: 91), rice farming settlements disappear from the archaeological record during the third century BCE, reappearing again in the first century CE. Ahn suggests that the specialized nature of intensive rice paddy farming might have been especially vulnerable to environmental fluctuations, but he acknowledges that there is no evidence for major climatic changes that might have triggered a hiatus in rice farming during this period (Ahn 2010: 97). The hiatus in wet rice sites coincides with the emergence of the Korean-style bronze dagger culture in the third century BCE. As described by Ahn (2003), this culture spreads from the Kŭm river basin on the west coast of Korea. In addition to its characteristic bronze daggers, this culture is characterized by coarse patterned bronze mirrors with multiple attachment loops (多鈕粗文鏡), shield- and hilt-shaped bronze implements, black long-necked earthenware, and clay-rimmed ceramics. Ahn emphasizes that the ceramic style, pattern of settlement, and burial styles of this culture indicate a break with the previous Mumun culture, although the two cultures continue to coexist for some time. The Korean-style bronze dagger itself descends from the Liaoning bronze dagger prototype. The Liaoning prototype is found in the Korean peninsula from 1300 BCE on and in Kyūshū from 800 BCE, but Ahn (2003) dismisses the possibility that the distinctive Korean-style bronze dagger developed from this prototype within the Korean peninusla. Instead, he traces the origins of the Korean bronze dagger culture to the central Liaoning region, where similar pottery, burial, and dwelling styles are found in association with the Liaoning bronze dagger prototype. According to Ahn, this Liaoning culture split into two branches, one of which remained in Liaodong and the Changbaishan region. The second branch brought the Korean-style bronze dagger culture to the Kŭm river area. Ahn writes of this culture: “Agricultural settlements disappeared from the archaeological record from the third century B.C. when the Late Mumun culture,Footnote 3 with a nomadic lifestyle, spread from the Liaoning region of northeast China” (Ahn 2010: 91). It is not clear to what extent the Korean-style bronze dagger culture should be characterized as nomadic, but it is clear that it was not, in its initial appearance, associated with wet rice cultivation. The advent of this culture can account for the temporary disappearance of wet rice farming settlements between the third century BCE–first century CE.

Early Chinese sources on the Korean peninsula and the Japanese archipelago

The earliest substantial Chinese sources on populations in the central/south Korean peninsula, the so-called Dongyi “Eastern barbarian” (Book of Wei) in the Wei shu section of the Sanguo zhi (late third century CE) and the Hou Han shu (fifth century CE), describe three groupings of peoples, the so-called Samhan “Three Han” (三韓 Sanhan): Mahan (馬韓) in the west central region, Chinhan (辰韓 Chenhan) in the southeast, and Pyŏnhan (弁韓 Bianhan) in the south.Footnote 4 Traditional Korean historiography indentifies these groupings as the antecedents of the historical polities Paekche (百済), Silla (新羅), and Kaya (加耶), respectively. Inscriptional evidence indicates that the term Han 韓 had ethnonymic significance not only for the Chinese authors of the Wei shu and Hou Han shu but for local Sinoxenic peoples as well. Thus, the inventory of gravekeeper villages on the 414 CE stele memorializing Koguryŏ king Kwangaet’o (廣開土) lists both Koguryŏ 高句麗 and Han 韓 villages, without distinguishing the latter as Mahan, Chinhan, etc. Nevertheless, the Wei shu and Hou Han shu present a picture of some ethnic and linguistic diversity in the Samhan region in the third century.

The Wei shu describes the language of Chinhan as “not the same as that of Mahan” (其言語不與馬韓同).Footnote 5 While the people of Mahan are described as not knowing how to use cows and horses as means of transport (不知乗牛馬), those of Chinhan use them. The latter are described as planting the five crops with the addition of rice (宜種五穀及稻), suggesting that the latter may have been something of an add-on.

The Wei shu describes the Pyŏnhan and Chinhan populations as “living intermingled together” (弁辰與辰韓雑居). It describes their clothing and dwellings as the same, and their languages and customs as similar (言語法俗相似). The Hou Han shu begins with the same phrase about intermingled living, then states “enclosed towns and clothing are all the same” (城郭衣服皆同) but “languages and customs have differences” (言語風俗有異). This section of the Hou Han shu, as the later of the two texts, often cites the Wei shu, but the Hou Han shu drew on other sources as well. The different descriptions of linguistic and cultural distinctions may reflect differing responses to a situation of ethnic complexity. Similar complexity is suggested by the descriptions of physical type. The Wei shu states that “Chinhan men and women are close to Wa (男女近倭),” the ethyonym for the contemporary inhabitants of the Japanese archipelago, and like the Wa tattoo their bodies. The Hou Han shu identifies this as a feature of Pyŏnhan, stating that “their country is close to Wa, therefore they frequently have tattoos.”

Linguistic differences are confirmed by the Wei shu toponyms for the Samhan. The Wei shu gives phonogrammatic spellings for 54 Mahan settlement names. As pointed out by Toh (2008: 234–5), most are disyllabic: 34 are transcribed with two syllables, 10 more with two syllables and a suffix, one of which is identifiable as *-pieliai 卑離, usually related to the Paekche word puri <夫里> “town,” itself typically compared to Late Middle Korean -βɨr “town.”Footnote 6 These suffixes do not occur in the Chinhan and Pyŏnhan settlement names. The Wei shu lists the latter together in no particular order. It prefixes the Pyŏnhan names with Pyŏnjin 弁辰. However, the Chinhan and Pyŏnhan toponyms also appear to draw on two distinct linguistic traditions. All but one of the 12 Chinhan names are disyllabic (like the Mahan names). Five of the 12 Pyŏnhan names have three or more syllables, and three of these appear to involve a suffix, *-mietoŋ 彌凍and *-jamaʔ 邪馬. The first of these suffixes also occurs in the only Chinhan polysyllabic settlement name.Footnote 7 The second is identical to the transcription given in the Wei zhi for the first two syllables for the contemporary *Jamaʔdə “Yamato” grouping in the Japanese archipelago. Scholars generally intepret these as involving a morpheme cognate with proto-Japonic *jama “mountain” (Bentley 2008: 14). A virtually identical spelling *jama 邪麻 occurs as an independent word in the Wa toponyms on the Japanese archipelago given in the Wei shu.

In light of the discussion in the “Hiatus in wet rice agriculture on the Korean peninsula” section, a simplistic interpretation of the Wei shu and Hou Han shu descriptions might be that the three Han groupings correspond to three distinct but related ethnicities. In fact, the texts indicate a more complex (and plausible) interrelationship between language, ethnicity, and protopolitical grouping. Mahan, the larger, better established grouping, occupies the area where the Korean-style bronze dagger culture emerged some five centuries earlier. Chinhan represents a population more recently arrived from the northwest, as indicated by its oral traditions and its mastery of animal husbandry. The Chinhan population lives intermixed with Pyŏnhan; the Chinese reporters struggle to decribe the resultant demographic complexity. Their languages may be similar, or different; some resemble the Wa, some tattoo their bodies. While Wa-like toponyms are more frequent in the Pyŏnhan grouping, one such toponym is identified with Chinhan. This is exactly the kind of complexity we might expect to be associated with the situation described by Ahn, where a population associated with Mumun wet rice growing culture lives alongside more recently arrived members of the Korean-style bronze dagger culture.

Linguistics

Toponymic evidence on language locations

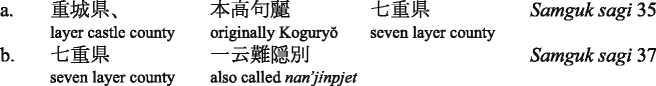

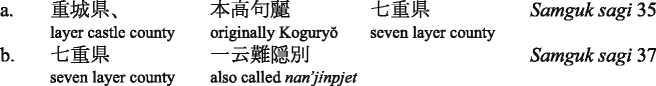

Clear evidence for the presence of a Japonic language or languages on the Korean peninsula is provided by the so-called Koguryŏ placenames recorded in the gazetteer chapters 35 and 37 of the twelfth century Korean history Samguk sagi (三國史記 Record of the Three Kingdoms). The crucial data have been known since Shinmura (1916). It consists of entries where a Silla toponym is paired with the original Koguryŏ name for a locality that came under Silla control after the Koguryŏ defeat in 668. Some of the Koguryŏ toponyms renamed by Silla are phonogrammatic, or have an alternate name that is phonogrammatic. A subset of the phonogrammatically transcribed names appears to be related to the meaning of the later Koguryŏ or Silla names.Footnote 8 For example,

-

1.

(1a) gives the Silla toponym, obviously shortened from the Koguryŏ name. (1b) gives the Koguryŏ name cited in (1a), plus an alternate phonogrammatic name. The phonogrammatic name is a good fit with “seven layer,” if the former is read as something resembling nan’jɨn (cf. proto-Japonic nana “seven”) and pjet (cf. pJ pe “layer,” Late Middle Korean pʌr id.)Footnote 9

There are two broad interpretations of the Koguryŏ phonogrammatic material. One takes them to represent the Koguryŏ language. This interpretation is adopted in earlier Japanese scholarship, by the Korean scholar Lee Ki-moon (see Lee and Ramsey 2011) and by Christopher Beckwith (see Beckwith 2007). It has been influential among anthropologists, e.g., Hudson (1999). The second interpretation, associated with the Japanese scholar Kōno Rokurō and the Korean linguist Kim Bang-han (Kim 1983), claims that the Koguryŏ phonogrammatic material transcribes the toponyms of linguistically distinct, non-Koguryŏ peoples.

Scholars adopting the first view have arrived at diametrically opposed conclusions about the nature of the Koguryŏ language. Thus, Lee and Ramsey (2011) emphasize the lexical material in the Koguryŏ language relatable to Korean,Footnote 10 while Beckwith (2007) considers Koguryŏ to be a continental relative of Japanese. In contrast, the second view explains why the Koguryŏ phonogrammatic material transcribes words relatable to Japonic and words related to Koreanic. Koguryŏ used phonograms to transcribe indigenous names from languages other than their own. They also devised standard Chinese binomic names for some localities that came under their control; for such localities, the two names coexisted.

From the standpoint of this paper, the important takeaway lesson from the Koguryŏ toponymic data is that a language cognate to Japonic was spoken on the Korean peninsula. This is a point of consensus for all major scholars who have worked on this material. The range of the Koguryŏ toponymns is confined to the region of historical Koguryŏ control, so they provide no information about the southern tip of the peninsula, but the northern range of phonogrammatic toponyms with widely accepted Japonic interpretations extends as far as modern North Hwanghae province, south of the later Koguryŏ capital at P’yŏngyang.

Chronological depth of language families

Both Japonic and Koreanic are relatively shallow language families. Comparative phonological evidence shows proto-Japonic to be somewhat older that the oldest extensive textual attestations of Western Old Japanese in the eighth century. Proto-Ryūkyūan maintains the distinction between proto-Japonic *e and *i and *o and *u in wider range of environments than does Western Old Japanese, indicating that the ancestor of pR diverged from a parent older than WOJ (Hattori 1977–1979). Phonological information like this provides a ceiling but not a floor for the date of the protofamily; however, a radically earlier date would lead us to expect a greater degree of phonological divergence. Hattori’s (1953) glottochronological study estimates a date of 500 CE for the divergence of the ancestors of Early Middle Japanese and Shuri Ryūkyūan. Hattori arrives at this date by adjusting the logarithmic decay function proposed by Swadesh to fit the facts of several known cases of divergence.

A standard criticism of glottochronology is that it assumes a constant rate of vocabulary replacement across languages. In a recent paper, Lee and Hasegawa (2011) attempt to overcome this and other defects of glottochronological approaches using a Bayesian phylogenetic analysis based on lexical data from 59 Japonic varieties. This model assumes a single rate of vocabulary substitution across varieties, but the rate is calibrated on the basis of known historical dates (in this case, those for Western Old Japanese and Early Middle Japanese). The phylogeny selected by Hasegawa and Lee is problematic in its shallower branches, which represent all non-Ryūkyūan branches as descended from EMJ, but it is not clear that this affects their overall results. Lee and Hasegawa estimate a date of 2182 BP for the ancestor of proto-Japonic. This result is important because it disconfirms the possibility of Kofun period (third to sixth century CE) date for pJ, something not completely disallowed by Hattori’s results. However, a Kofun period date for pJ would also be inconsistent with the toponymic evidence for Japonic on the Korean peninsula, unless the toponyms somehow resulted from a later historical movement of Japonic speakers to the continent.

Phonological evidence indicates that proto-Koreanic is even shallower than proto-Japanese. The evidence is similar: data from the Cheju variety show a broader distribution of the back central unrounded vowel/ʌ/than is found in fifteenth century Late Middle Korean texts. Once again, this gives us a ceiling for divergence somewhat earlier than the fifteenth century; once again, if the protolanguage was radically older, we might expect greater phonological divergence.

Neither the phonological evidence nor the statistical evidence (in the case of Japanese) is consistent with a date of protolanguage divergence older than the dates for the beginning of wet rice agriculture, as pointed out by Hudson (1999) and Lee and Hasegawa (2011). This fact alone does not rule out the possibility that proto-Japanese descends from a pre-Yayoi Jōmon language, or proto-Korean from a pre-Mumun Chulmun language. In either case, it is a prima facie possibility that such a language, indigenous to the region prior to the arrival of wet rice agriculture, expanded and replaced previously existing indigenous languages as a result of the demographic expansion associated with the new agricultural technology. In the case of Japonic, however, once again, such a scenario would have a difficult time explaining the toponymic evidence for Japonic on the Korean peninsula.

The scenarios whereby Japonic arrived in the archipelago and dispersed as a result of the Yayoi expansion, and Koreanic arrived in the peninsula and dispersed as a result of the advent of the Korean bronze curved dagger culture, are consistent with the farming/language dispersal model (Bellwood and Renfrew 2002). The dates of these two events, 950 BCE and 300 BCE, respectively, are also consistent with the gap between the chronological ceilings for dispersal of the two families, before 700 CE for Japonic and before 1,450 CE for Koreanic. In both instances, we know that the actual date of dispersal must be earlier, but we do not know how much. Even Lee and Hasegawa’s date, first century BCE, leaves a 900-year lag between the archaeological event and the linguistic evidence for dispersal.

The remarkable non-diversity of Japonic and Koreanic can be explained by two factors. The first is a founder’s effect, the phenomenon by which genetic diversity is reduced when a small population settles a new area. The claim that a serial founder’s effect is discernible in linguistic variation has been made by Atkinson (2011), among others. In the case of Japonic, we might expect founder’s effects to have occurred as a result of the movement of relatively small populations from the Korean peninsula to Kyūshū, and again from Kyūshū to the rest of the archipelago. Crudely put, the effect can be conceptualized as a local reduction in linguistic diversity compared to the home population. The same effect would be anticipated in the establishment of Koreanic in the south central peninsula, and again as it expanded throughout the peninsula.

The second factor is archaeohistorical. Both the Yayoi expansion in Japan and the spread of the Korean bronze curved dagger culture were subject to bottleneck effects, to borrow another term from evolutionary science. Kobayashi (2007) accounts for the relatively slow spread of Yayoi culture to the east in terms of the “walls” (壁 kabe) put up by the progressively more robust Jōmon cultures to the east in the archipelago. In the case of Korea, the Chinese commanderies in the north of the peninsula imposed a bottleneck until their demise in the early fourth century CE. Release of each bottleneck results in a new dispersal and founders effect. These effects leave phonological traces; thus, the categories of lexical accent are less complex in eastern Japonic varieties, while Koreanic varieties in regions to the north and east, as well as Cheju, lack lexical pitch accent altogether.

Note that the founders effect scenario presupposes demic diffusion. Thus, the relative nondiversity of Koreanic and Japonic provides further support for the view that the speakers of the protolanguages arrived from elsewhere.

Rice and related agricultural vocabularies

Vovin (1998) discusses possible external cognates for the ten Japanese terms related to rice agriculture in (2). The proto-Japonic reconstructions I cite are slightly different from Vovin’s.

-

2.

-

(a)

*jinaC 2.4 “riceplant”Footnote 11

-

(b)

*mə/omi 2.1 unhulled rice

-

(c)

*jənaC 2.1 “hulled rice”

-

(d)

*kəmə/aC 2.3 “(hulled) rice”

-

(e)

*ipi 2.3 “cooked rice”

-

(f)

*po 1.3a “ear of grain”

-

(g)

*ta 1.3a “ricefield”

-

(h)

*nuka ?2.3 “rice bran”

-

(i)

*ko “flour, powder”

-

(j)

*nəri “starch, rice glue”

-

(a)

Vovin suggests cognates for four of these, (2e), (2g), (2i), and (2j) from Koreanic, with cognates for (2e) in Tungusic and Turkic, for (2g) in Mongolic and Turkic, and for (2i) in Tungusic as well. He finds no external etymologies for (2b), (2c), and (2h). Vovin specifically rejects Austronesian cognates proposed in earlier research, but he suggests Austroasiatic cognates for (2a), (2d), and (2f). Sagart (this issue) has proposed an alternative Sino-Tibetan-Austronesian etymology for (2d).

As this discussion suggests, it is not a straightforward matter to identify cognates in this lexical domain in Northeast Asia, and it is not straightforward to distinguish inherited cognates from loans. In this section, I will confine myself to some general observations about rice-related vocabularies in Korean and Japanese and possible relations between them as they relate to the Shandong–Liaodong dispersal hypothesis.

As Vovin observes, some of the items in (2) are the products of internal semantic specialization, such as (2b) *mə/omi “unhulled rice” < *mə/om- “pound” + *-i nominalizer, and (2e) *ipi “cooked rice,” which Vovin derives in a similar way from a verb *ip- “eat.” These derivations raise the possibility that the ancestor language lacked specialized terms for “unhulled rice” and “cooked rice.” Similarly, (2f) and (2i) are not specialized rice-related terms. The lack of specialized vocabulary specifically dedicated to rice is more visible in Korean, where the terms in the semantic role of (2c-d) psʌr H < *pʌsʌr and (2e) pap L both designate hulled and cooked grains, respectively, of any type. The Korean (and Altaic) cognates that Vovin suggests for (2e), (2g), (2i), and (2j) are all unspecialized: they mean “eat,” “field, plain,” “flour, powder,” and “malt.” Corresponding to (2), the only semantic category with a Korean term specialized for rice is (2a) Late Middle Korean pjə H “riceplant.”

These facts are consistent with the Shandong/Liaodong dispersion hypothesis outlined in “The Shandong/Liaodong dispersion hypothesis” section. If the language families commonly grouped together as Altaic are related to Japonic, they presumably dispersed from Shandong prior to Japonic since their historical ranges are more remote. Even in the case of Koreanic, if Ahn’s hypothesis that the Korean-style bronze dagger culture entered the peninsula from central Liaoning is correct, Koreanic may represent an earlier, pre-rice cultivation dispersion from Shandong. Any rice cultivators left behind in the greater Shandong region after Miyamoto’s third dispersion were absorbed by the expansion of Sinitic, so no trace of their languages remain there. Cognate vocabulary between the surviving languages dispersed from Shandong precedes rice cultivation.

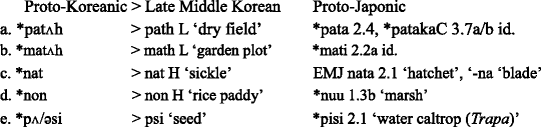

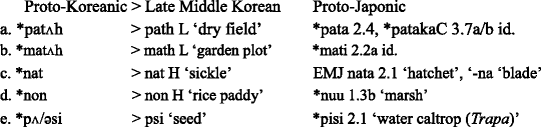

This interpretation is supported by the semantics of cognate agricultural vocabulary in Korean and Japanese, as illustrated in (3).

-

(3)

(3a–c) are excellent semantic and phonological fits, but they are often rejected as loans (e.g., Vovin 2010) on the assumption that agricultural vocabulary is too recent to be inherited. But none of these terms are dedicated to rice agriculture. Given the antiquity of the first Shandong/Liaodong dispersion (5500 BP), these terms may represent a shared inheritance as old as five millennia. (3d) is a rice-related term in Koreanic, but if the Japonic item is cognate, the original meaning was not specialized for rice agriculture. (3e) also represents a semantic shift, and an item unrelated to rice. The Japanese term must be quite old since it provides an etymology for Chinese bíqí 荸薺 < pidzej “Chinese water chestnut” (Eleocharis dulcis), which is otherwise unetymologized.

Summing up the results of this section, Japonic gives some evidence for agricultural vocabulary cognate with other languages in Northeaast Asia, but none of this vocabulary is dedicated to rice. Koreanic shows relatively little vocabulary dedicated to rice at all. These facts are consistent with a dispersal of some languages, including Koreanic, from Shandong prior to the advent of wet field rice cultivation in that area. The cognate agricultural vocabulary shared by Koreanic and Japonic precedes wet rice agriculture.

Conclusion

In this paper, I have sketched a specific historical scenario that attempts to explain the linguistic ecology of the non-Sinitic language families in Northeast Asia associated with wet rice agriculture, Japonic and Koreanic. This scenario is couched within the general hypothesis of a diffusion of agriculture from the area around the Shandong peninsula to the north and east. According to the scenario, Japonic arrives in the Korean peninsula around 1500 BCE and is brought to the Japanese archipelago by the Yayoi expansion around 950 BCE. On this view, the language family associated with both Mumun and Yayoi culture is Japonic, although the association of a culture in the archaeological sense with a single language family is almost certainly an oversimplification.Footnote 12

Koreanic arrives in the south-central part of the Korean peninsula around 300 BCE with the advent of the Korean-style bronze dagger culture. Its speakers coexist with the descendants of Mumun cultivators, and thus with Japonic, well into the common era. Each of these demic diffusions, as well as the later dispersions of Koreanic and Japonic, result in founder effects which diminish the internal variety of the language family. Japonic and Koreanic, as well as possibly other Northeast Asian languages, share some agricultural vocabulary, but this shared vocacbulary precedes rice farming.

Notes

This paper is not the place to offer yet another reassessment of the Altaic hypothesis, but to this linguist’s eye the most persuasive argument for the hypothesis are the formal and functional similarities between verbal nominalizing morphology in Mongolic, Tungusic, and Turkic (Ramstedt 1952), extended to Koreanic in suggestions by Ramstedt and Poppe and to Japonic by Vovin (2001) and Robbeets (2007).

In this article, I follow the revised dates for the beginning of the Yayoi period in Kyūshū established over the past decade by a team at the National Museum of Japanese History (Nishimoto ed. 2006) based on accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon dating. These dates cluster around 3050 BP, that is, 950 BCE (Harunari and Imamura 2004). There has been some resistance from the community of Japanese archaeologists to the revised dates, due the interpretation of external evidence for the beginning of Yayoi, based on the dating of bronze daggers originating in the Liaoning region and found throughout the Korean peninsula and Kyūshū. For an attempt to reconcile the AMS dates and the external evidence, see Harunari (2006). In any case, there is a consensus among Japanese archaeologists that the beginning of Yayoi should be revised to a date earlier by at least three centuries than the traditional 500 BCE.

Ahn (2010) uses the term “Late Mumun culture” to refer to the culture designated as the Korean-style bronze dagger culture (Hanguk-sik tongkŏm munhwa 韓国式銅剣文化).

Pyŏnhan is referred to in the Wei shu as Pyŏnjin 弁辰, usually interpreted as an amalgamation of the names for Pyŏnhan and Chinhan. The name further emphasizes the heterogeneous nature of this grouping.

The passage goes on to compare the language of Chinhan with that of the Chinese Qin 秦 state. It cites what it identifies as the Qin words for “country” (邦), “bow” (弧), “bandit” (冦), and “drinking game” (行觴), and claims that the Chinhan words are the same. It also states that the Chinhan people identify themselves with the inhabitants of the Chinese Lelang commandery in northwest Korea: “They say that the people of Lelang were originally the remnants of their people” (謂樂浪人本其殘餘人). While scholars have generally dismissed this apparent attempt to claim a Chinese ethnicity, it may in fact reflect the relatively recent arrival of the Chinhan population from the northwest.

Interpreted as a place name suffix, *-mietoŋ 彌凍is comparable to Late Middle Korean mith “base, bottom” and proto-Japonic *mətə id., asserted by Martin (1966) to be cognate. The latter is a common second element in toponyms. The comparison would have to assume that the first syllable vowel assimilated to the second in pJ.

For the purposes of this paper, I interpret the Koguryŏ phonograms following the Middle Chinese system of Baxter and Sagart (n.d.). Korean scholars typically interpret them by their Sino-Korean values, but Beckwith (2007) is surely correct to argue that Sino-Koguryŏ represents a distinct sinoxenic tradition since Sino-Korean is generally dated to the late Tang period.

Lee and Ramsey acknowledge that the four numerals attested in the Koguryŏ phonogrammatic tradition “all look remarkably like Japanese” (2011: 43). They then state “At the same time, however, the vocabulary found in the Koguryŏ place names includes even more elements that relate solidly to Middle Korean and thus to the mainstream development of the Korean language” (ibid). They give no statistics to support this assessment. They also do not explain how a language whose lexicon preponderantly relates “solidly to Korean” should come to have all four of its attested basic numerals remarkably similar to Japanese.

Vovin, following a proposal of Unger (1977), reconstructs pJ *zinaCi for “riceplant,” on the basis of attestations such as arasine “unhulled rice” < ara “rough” + (s)ine, misine “riceplant,” mi- honorific + (s)ine. Unger’s hypothesis was that *z was lost in initial position but retained medially as WOJ /s/. Because the evidence for a voiced obstruent series in proto-Japanese is weak, I have not followed Unger and Vovin in reconstructing *z, but instead exploited the independently motivated glide *j. The reconstruction posits glide strengthening in medial position, which may seem counterintuitive, but in fact, strengthening is limited to initial position after a compound boundary.

There are points of contact between the hypothesis advanced in this paper and the proposals of Unger (2009) and Vovin (2011, to appear). Both Unger and Vovin associate proto-Japonic with demic diffusion from the Korean peninsula to the Japanese archipelago at the beginning of the Yayoi period. Unger however argues that rice agriculture reached the Korean peninsula from the south. Vovin holds, as I have suggested here, that Koreanic entered the peninsula from the north and displaced the previous Japonic-speaking population, but he associates this event with a horseriding culture equipped with iron weapons. In contrast, I have related the diffusion of Japonic and Koreanic with two specific archaeological events: the Mumun–Yayoi diffusion through the peninsula into the archipelago from 1500–950 BCE and the diffusion of the Korean-style bronze dagger culture from 300 BCE.

References

Ahn S-M. Kogohak ŭro pon Han minjok ŭi kyet’ong [The lineage of the Korean people from the viewpoint of archaeology]. Hanguk sa simin kangchwa [The Citizens’ Forum on Korean History] 2003;32:98–102. Ilchogak, Seoul.

Ahn S-M. The emergence of rice agriculture in Korea: archaeobotanical perspectives. In: Hosoya L, Sato Y, Fuller D, editors. Archaeological and anthropological sciences 2 (Special issue, The Archaeobotany of Asian Rice). 2010. p. 89–98.

Atkinson Q. Phonemic diversity supports a serial founder effect model of language expansion from Africa. Science. 2011;332(6027):346–9.

Baxter, W, Sagart, L. (n.d.) Baxter-Sagart Old Chinese reconstruction (Version 1.00). Online at http://crlao.ehess.fr/document.php?id=1217. Accessed 18 Dec 2011.

Beckwith C. Koguryo, the language of Japan’s continental relatives: an introduction to the historical-comparative study of the Japanese-Koguryoic languages with a preliminary description of Archaic Northeastern Middle Chinese. Leiden: Brill; 2007.

Bellwood P, Renfrew C. Examining the farming/language dispersal hypothesis. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research; 2002.

Bentley J. The search for the language of Yamatai. Jpn Lang Lit. 2008;42:1–43.

Crawford GW, Lee G-A. Agricultural origins in the Korean Peninsula. Antiquity. 2003;77:87–95.

Georg S, Michalove PA, Manaster Ramer A, Sidwell PJ. Telling general linguists about Altaic. J Linguist. 1999;35:65–98.

Franke H. The forest peoples of Manchuria: Kitans and Jurchens. In: Sinor D, editor. The Cambridge history of Inner Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990. p. 400–23.

Haugen, E. The ecology of language; essays by Einar Haugen. Selected and introduced by Anwar S. Dil. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1972.

Harunari H. Yayoi jidai no nendai mondai [The problem of the dating of the Yayoi period]. In: Nishimoto T, editor. Yayoi jidai no shin nendai (Shin Yayoi jidai no hajimari 1) [The new dating of the Yayoi period (The beginning of the Yayoi period revisited)]. Tokyo: Yuzankaku; 2006. p. 65–89.

Harunari H, Imamura M. Yayoi jidai no jitsu nendai [The actual date of the Yayoi period]. Tokyo: Gakuseisha; 2004.

Hattori S. On the method of glottochronology and the time depth of Proto-Japanese. Gengo kenkyū. 1953;22(23):29–77.

Hattori S. Nihon sogo ni tsuite [Regarding proto-Japonic] 1–22. Gekkan gengo. 1977–1979;7(1)–7(3), 7(6)–8(12).

Hudson M. The ruins of identity. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press; 1999.

Janhunen, J. Ethnicity and language in prehistoric Northeast Asia. In: Blench R, Spriggs M, editors. Archaeology and language II. London: Routledge; 1998. p. 195–208.

Kim B-H. Hangukŏ ŭi kyet’ong. Seoul: Minŭmsa; 1983.

Kobayashi A. Jōmon kara Yayoi e no tenkan [The transition from Jōmon to Yayoi]. In: Hirose K, editor. Yayoi jidai wa dō kawaru ka [How does the Yayoi period change]. Tokyo: Gakuseisha; 2007. p. 135–57.

Kuzmin Y. Geoarchaeology of prehistoric cultural complexes in the Russian Far East: Recent progress and problems. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 28; 2008. p. 3–10.

Lee K-M, Ramsey R. A history of the Korean language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011.

Lee S, Hasegawa T. Bayesian phylogenetic analysis supports an agricultural origin of Japonic languages. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2011. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0518. http://rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/early/2011/05/04/rspb.2011.0518.full. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

Martin SE. Lexical evidence relating Korean to Japanese. Language. 1966;42(2):185–251.

Miyamoto K. Nōkō no kigen o saguru: Ine no kita michi [Searching for the origins of agriculture: the road by which rice came]. Tokyo: Yoshikawa kōbunkan; 2009.

Nishimoto T, editor. Yayoi jidai no shin nendai [The new dating of the Yayoi period]. Tokyo: Yuzankaku; 2006.

Poppe N. Vergleichende Grammatik der altaischen Sprachen. Teil I. Vergleichende Lautlehre [Comparative Grammar of the Altaic Languages, Part 1: Comparative Phonology]. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz; 1960.

Ramstedt GJ. Einführung in die altaische Sprachwissenschaft II. Formenlehre. In: Aalto P, editor. Introduction to Altaic linguistics, volume 2: morphology. Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura; 1952.

Robbeets M. Is Japanese related to Korean, Tungusic, Mongolic and Turkic? Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz; 2005.

Robbeets M. How the actional suffix chain connects Japanese to Altaic. Turk Lang. 2007;11(1):3–58.

Schuessler A. ABC etymological dictionary of Old Chinese. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press; 2007.

Shinmura I. Kokugo oyobi chōsengo no sūshi ni tsuite [Regarding numerals in Japanese and Korean]. Geibun. 1916;7(2):4.

Starostin SA, Dybo AV, Mudrak OA. Etymological dictionary of the Altaic languages. Leiden: Brill; 2003.

Toh SH. Samhan ŏ yŏngu [Research on Samhan language]. Seoul: Che-i-aen-ssi; 2008.

Unger JM. Studies in early Japanese morphophonemics. 2nd ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club; 1977. 1993.

Unger JM. The role of contact in the origins of the Japanese and Korean languages. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press; 2009.

Vovin A. Japanese rice agriculture terminology. In: Blench R, editor. Archaeology and language II. London: Routledge; 1998. p. 366–78.

Vovin A. Japanese, Korean, and Tungusic: evidence for genetic relationship from verbal morphology. In: Honey DB, Wright DC, editors. Altaic Affinities, Proceedings of the 40th Meeting of PIAC. Bloomington: Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies, University of Indiana; 2001. p. 83–202.

Vovin A. The end of the Altaic controversy. Cent Asiat J. 2005;49(1):71–132.

Vovin A. Koreo-Japonica: a re-evaluation of a common genetic origin. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press; 2010.

Vovin A. From Koguryŏ to T’amna—slowly riding to the South with speakers of Proto-Korean—Ms. University of Hawai’i at Mānoa; 2011. To appear in Korean Linguistics 15.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Whitman, J. Northeast Asian Linguistic Ecology and the Advent of Rice Agriculture in Korea and Japan. Rice 4, 149–158 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12284-011-9080-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12284-011-9080-0