Abstract

Growing evidence indicates that inflammatory reactions play an important role in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease (ALD). The implication of immunity in fueling chronic inflammation in ALD has emerged from clinical and experimental evidence showing the recruitment and the activation of lymphocytes in the inflammatory infiltrates of ALD and has received further support by the recent demonstration of a role of Th17 lymphocytes in alcoholic hepatitis. Nonetheless, the mechanisms by which alcohol triggers adaptive immune responses are still incompletely characterized. Patients with advanced ALD show a high prevalence of circulating IgG and T-lymphocytes towards epitopes derived from protein modification by hydroxyethyl free radicals (HER) and end-products of lipid peroxidation. In both chronic alcohol-fed rats and heavy drinkers the elevation of IgG against lipid peroxidation-derived antigens is associated with an increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines and with the severity of histological signs of liver inflammation. Moreover, CYP2E1-alkylation by HER favors the development of anti-CYP2E1 auto-antibodies in a sub-set of ALD patients. Altogether, these results suggest that allo- and auto-immune reactions triggered by oxidative stress might contribute to fuel chronic hepatic inflammation during the progression of ALD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD) encompasses a broad spectrum of histological features ranging from steatosis with minimal parenchymal injury to steato-hepatitis and fibrosis/cirrhosis. While almost all heavy drinkers develop steatosis, only 10–35% of them show various degrees of alcoholic hepatitis and 8–20% progress to cirrhosis [83]. It is increasingly evident that chronic inflammation represents the driving force in the evolution of alcohol liver injury to steato-hepatitis and fibrosis/cirrhosis. Accordingly, the hepatic expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines precedes the development of histological signs of necro-inflammation in chronic alcohol-fed rats [59], while steato-hepatitis is associated with leucocyte focal infiltration and elevated circulating levels cytokines/chemokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8/CINC, and macrophage chemotatic protein-1 (MCP-1) [5, 19, 36, 40].

Several mechanisms might account for the stimulation of hepatic inflammation by ethanol. Early studies have proposed the involvement of an increased translocation of gut-derived endotoxins to the portal circulation [19, 54]. More recent experimental data demonstrate that ethanol itself also enhances the capacity of Kupffer cells to respond to pro-inflammatory stimuli. In particular, alcohol exposure up-regulates the expression of tool-like receptors [24] and enhances the signals controlling the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines mediated by the nuclear transcription factors kB (NFkB) and Early Growth Response-1 (Erg-1) and by JNK, ERK, and p-38 protein kinases [40, 42, 47, 71]. Moreover, alcohol consumption increases the pro-inflammatory activity of liver Natural Killer T-cells (NKT) [44] and promotes the hepatocyte production of chemokines such as IL-8, MCP-1, and MIP-1 [20] that drive inflammatory cells to the hepatic parenchyma. Finally, a further contribution to inflammation in ALD might involve alcohol effects on osteopontin and the adipokines leptin, and adiponectin. Osteopontin is a cytokine produced by many tissues that enhances pro-inflammatory Th-1 responses and lymphocyte survival. An increase in the liver production of osteopontin has been associated with the extent of inflammation in alcohol-fed rodents [60] and hepatic osteopontin mRNA expression is higher in patients with alcoholic hepatitis than in heavy drinkers with fatty liver only [64]. Leptin and adiponectin originating from the adipose tissue are increasingly recognized to influence the inflammatory status of many tissues including the liver [74]. Leptin has a pro-inflammatory action and stimulates lymphocyte survival and proliferation favoring Th-1 reactions, while adiponectin blunts pro-inflammatory cytokine production and depresses the proliferation and activation of both B- and T-cells [33]. Alcohol has opposite effects on adipokines, as serum leptin is increased in patients with ALD [49], whereas chronic ethanol feeding decreases adiponectin secretion in the early phase of alcohol injury in rodents [28, 67] enhancing macrophage response to endotoxins [21].

Beside the activation of liver innate immunity, ALD pathogenesis also involves adaptive immunity. Early studies in ALD patients have detected circulating antibodies targeting alcohol-altered autologous hepatocytes [52]. In alcohol abusers, polyclonal hyper-production of gamma globulins is also frequent in association with IgA deposition in many tissues [36]. Moreover, ALD patients not rarely have signs of auto-immune reactions consisting in the presence of circulating antibodies directed against non-organ-specific and liver-specific auto-antigens [41]. In particular, anti-phospholipid antibodies can be observed in up to 80% of patients with alcoholic hepatitis or cirrhosis, but are not infrequent in heavy drinkers with milder liver damage [7, 10]. In agreement with these observations, histology reveals that the neutrophil-rich liver infiltrate characteristic of alcoholic hepatitis also contain both CD8+ and CD4+ T-lymphocytes [9]. Furthermore, T-cells from both chronic alcohol-treated mice or alcohol abusers over-express activation or memory markers and rapidly respond to T-cell receptor stimulation by producing interferon-γ (INF-γ) and TNF-α [65, 66]. The predominance of a Th-1 pattern (high TNF-α, INF-γ, IL-1) in cytokine production has also been observed in peripheral blood T-cells from active drinkers with or without ALD [35].

A new exciting input on the role of immunity in alcohol liver injury has come from a recent report demonstrating the activation of IL-17-producing T helper (Th17) lymphocytes in ALD and the specific contribution of IL-17 in promoting liver neutrophil infiltration during alcoholic hepatitis [37]. Th17 lymphocytes are a newly identified sub-set of effector helper T-cells distinct from Th-1 and Th-2 CD4+ T-cells and characterized by the preferential production of IL-17, IL-21, and IL-22. [6, 53]. Th17 cells have a prominent role in controlling defensive mechanisms to bacterial infections mediating a crucial crosstalk with epithelial tissues [6]. Moreover, Th17 lymphocytes are increasingly recognized to play an important role in driving inflammation during the evolution of chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases including inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis [73].

Oxidative stress as trigger of alcohol-induced immune reactions

The mechanisms by which alcohol triggers adaptive immunity are still incompletely characterized. In their pioneering study Israel and colleagues [25] have shown that the adducts originating from acetaldehyde binding to hepatic proteins cause the production of specific antibodies when injected into experimental animals. The presence of anti-acetaldehyde antibodies has been subsequently confirmed in rats chronically exposed to alcohol as well as in alcoholic patients [30, 50]. Although the immunization of ethanol-fed guinea pigs with acetaldehyde-modified hemoglobin reproduces several features of alcoholic hepatitis [84], the interest for acetaldehyde-induced immune responses is hampered by the uncertainty regarding identity of the antigens involved and by the low specificity for ALD of anti-acetaldehyde antibodies [29].

Subsequent researches have demonstrated that, by interacting with proteins, hydroxyethyl free radicals (HER) generated during cytochrome P4502E1- (CYP2E1) dependent ethanol oxidation represent a source of antigens distinct from those originating from acetaldehyde [45]. Accordingly, anti-HER IgG have been detected in chronically ethanol-fed rats as well as in alcohol abusers [1, 11]. Human anti-HER IgG recognize as main antigen HER-modified CYP2E1 [12], while the presence of anti-HER antibodies strictly correlates with CYP2E1 activity in both rodents and humans [2]. These observations, along with the demonstration of an oxidative stress-driven immunity in atherosclerosis and in several autoimmune diseases [32, 51], prompted us to investigate the possible implication of oxidative mechanisms in the immune responses associated with ALD.

It is well established that alcohol causes oxidative stress. Consistently, lipid peroxidation markers are increased in both the serum and the liver of ALD patients [3]. In this contest, we have observed that a large proportion (55–70%) of patients with biopsy-proven alcoholic hepatitis and/or cirrhosis have elevated titers of circulating IgG towards proteins adducted by lipid peroxidation-derived products such as malondialdehyde (MDA), 4-hydroxynonenal, and oxidized arachidonic acid [46]. During alcohol intake the reaction between acetaldehyde, MDA, and the ε-amino group of protein lysine residues also generates condensation products named malonildialdehyde-acetaldehyde adducts (MAA) [72]. MAA adducts have been detected in the liver of ethanol-fed rats [72] and their formation is responsible for the increased titers of IgG recognizing MAA-modified proteins detectable in patients with advanced ALD [57]. Furthermore, oxidative stress likely contributes to the development of anti-phospholipid antibodies in alcohol abusers, as oxidized phospholipids, namely oxidized cardiolipin and phosphatidylserine, are the main antigens recognized by anti-phospholipid antibodies isolated from the sera of ALD patients [56, 76]. In about 35% of the patients with advanced ALD the presence of anti-MDA antibodies is associated with the detection of peripheral blood CD4+ T-cells responsive to MDA adducts, indicating the capability of oxidative stress to trigger both humoral and cellular immune responses [68]. Interestingly, ethanol stimulates oxidative stress-dependent immunity also in chronic hepatitis C (CHC). Indeed, even moderate alcohol intake by CHC patients increases in a dose-dependent manner the prevalence of IgG targeting lipid peroxidation-derived antigens [55]. This is consistent with recent experimental observations about the synergy between ethanol and hepatitis C virus in promoting oxidative liver injury [13].

Possible mechanisms in the development of immune responses in alcoholic liver disease

The interaction between alcohol and the immune systems is complex. It is known since long time that excessive alcohol consumption affects the innate and adaptive immunity increasing the susceptibility to infections and compromising tissue response to injury [69]. Moreover, both acute and chronic alcohol intake depresses antigen-presenting capability of monocytes and dendritic cells, affects the of expression co-stimulatory molecules, and reduces T-cell proliferation [69].

In experiments performed with enteral alcohol-fed rats the hepatic expression of Th-1 cytokines (TNF-α, IL-12) m-RNAs shows a biphasic pattern with an early peak after 14 days of alcohol feeding and a secondary rise after 35 days [59]. Interestingly, all over the treatment alcohol suppresses the production of the Th-2 cytokine IL-4 and of the Th-2 regulator GATA3 [59], in accordance with the shift toward a Th-1 cytokine pattern observed in alcohol abusers [35]. The secondary increase in Th-1 cytokine RNAs is associated with the elevation of Th-1 regulators T-bet and Stat-4 and histological evidence of necro-inflammation [59]. Lipid peroxidation-derived antibodies are evident in concomitance with the late increase of Th-1 expression and the histological evidence of inflammatory infiltrates [59], while the anti-oxidant N-acetylcysteine reduces oxidative stress, lipid peroxidation-driven antibody production, and hepatic inflammation [58]. These observations suggest the possibility that, during the evolution of ALD, the increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines by endotoxin-activated Kupffer cells along with adipokine and osteopontin unbalances might overcome alcohol-dependent immune depression promoting the response of intraportal lymphoid follicles against antigens derived from oxidatively damaged hepatocytes [79]. This latter process is likely facilitated by the capacity of the scavenger receptors (SRA-1,2, CD36, SR-B1, LOX-1) and of some patter recognition receptors to recognize oxidized proteins and lipids [15]. Hepatic stellate cells (HSC) might represent an additional pathway for the presentation of oxidative stress-derived antigens to CD4+ T-cell, as HSC are efficient antigen-presenting cells [81] and have the capability to internalize oxidation products [63]. Hepatic steatosis and oxidative stress have also been shown to lower regulatory T-cell (Tregs) population in the liver [39]. This might represent an additional factor in the development of immune response in ALD, as Tregs have key immuno-regulatory functions and their impairment is critical for lymphocyte activation against oxidized antigens from LDL during the evolution of atherosclerosis [23].

Little is known about the origin of anti-phospholipid antibodies often associated with ALD. In the recent years increasing evidence has linked defects in the disposal of apoptotic cells with the development of anti-phospholipid antibodies [31, 62]. Current view suggests that an impaired macrophage clearance of apoptotic corpses might lead to secondary necrosis of non-ingested cells with the release of intracellular components capable to activate inflammation. In this context, apoptotic cells might be ingested by immature dendritic cells, promoting their maturation and the presentation of self-antigens to T-lymphocytes [31, 62]. Accordingly, anti-phospholipid antibody production can be induced in mice by the immunization with syngenic apoptotic lymphocytes, but not with viable cells [8]. We have observed that anti-phospholipid antibodies from the sera of ALD patients bind to apoptotic, but not to living cells, by specifically targeting oxidized phosphatidylserine expressed on the cell surface [76]. Such specificity is consistent with recent reports showing that phosphatidylserine is oxidized during apoptosis before being exposed on the outer layer of cell plasma membranes [27]. As chronic alcohol intake stimulates hepatocyte apoptosis [48] and impairs the capacity of neighboring hepatocytes to dispose of apoptotic bodies [43], it is possible that the accumulation of apoptotic hepatocytes may lead to the development of anti-phospholipid antibodies in ALD.

Oxidative stress and autoimmune reactions in alcoholic liver disease

As mentioned above, autoimmune reactions involving the presence of both non-organ-specific and liver-specific auto-antibodies are a common feature in ALD. Among these latter, we have observed that alcohol-fed rats as well as about 40% of the patients with advanced ALD have circulating IgG directed against CYP2E1 [28, 77]. Anti-CYP2E1 auto-antibodies from ALD patients are similar to those associated with halothane hepatitis and recognize at least two distinct conformational epitopes in the C-terminal portion of the molecule [78]. These epitopes are located in the molecule surface and account for the recognition by anti-CYP2E1 IgG of CYP2E1 expressed on the outer layer of the hepatocyte plasma membranes [78].

The breaching of self-tolerance toward anti-cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzyme is not rare in drug-induced hepatitis. This phenomenon has been explained by postulating that the binding of reactive drug metabolites to CYPs promotes humoral immune responses against the drug-derived epitope(s) and favors at the same time the activation of normally quiescent auto-reactive lymphocytes towards the carrier CYP molecules [75]. ALD patients with anti-HER antibodies have a fourfold increased risk of developing anti-CYP2E1 auto-reactivity as compared with patients without anti-HER IgG [77]. This indicates that CYP2E1 alkylation by HER is involved in the development of ALD anti-CYP2E1 auto-antibodies.

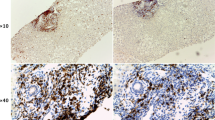

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) is a membrane receptor expressed by activated T-lymphocytes and by CD25+CD4+ Tregs that down-modulates T-cell-mediated responses to antigens [17]. Accordingly, CTLA-4 knockout mice show an expansion of CD4+/CD8+ T and B lymphocytes [16], while CTLA-4 polymorphisms in humans are genetic risk factors for several auto-immune diseases, including primary biliary cirrhosis and type-1 autoimmune hepatitis [17]. We have observed that CTLA-4 Thr17 → Ala substitution increases by 3.8 fold the risk of developing anti-CYP2E1 IgG without influencing the formation of anti-HER antibodies [77]. ALD patients having both anti-HER IgG and mutated CTLA-4 show a prevalence of anti-CYP2E1 auto-reactivity 23-fold higher than those negative for both these factors [77]. Thus, in a sub set of ALD patients the antigenic stimulation by HER-modified CYP2E1 in combination with an impaired control of T-cell proliferation due to mutated CTLA-4 promotes the breaking of self-tolerance. The actual clinical significance of these observations needs further investigations. Preliminary data show that high titers of anti-CYP2E1 auto-antibodies correlate with the extension of lymphocyte infiltration and the frequency of apoptotic hepatocytes, suggesting that in a sub-set of ALD autoimmune mechanisms might contribute to tissue injury.

Possible role of immunity in the progression of alcohol liver damage

Studies in atherosclerotic plaques have shown that the presentation of lipid peroxidation-derived antigens originating from oxidized low-density lipoproteins (LDL) to CD4+ T-cells leads to their Th-1 differentiation. On their turn, Th-1 cells produce TNF-α, and INF-γ and express CD40 ligand that stimulate macrophages to release pro-inflammatory mediators, reactive oxygen species, and proteases further stimulating LDL oxidation and local inflammation [18]. A similar scenario might also occur in ALD where endotoxemia along with alcohol-mediated Kupffer cell activation promotes the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines priming hepatic lymphocytes to respond to lipid peroxidation-derived antigens. The cytokines released by activated CD4+ T-cells can then further stimulate macrophage activation fueling in this way oxidative stress, parenchymal injury, hepatic inflammation, and collagen deposition.

Prior epidemiological prospective survey has shown an association between the presence of antibodies toward alcohol-modified hepatocytes and an increased risk of developing alcoholic liver cirrhosis [70]. At the same line, elevated titres of antibodies toward lipid peroxidation adducts and oxidized phospholipids are prevalent in heavy drinkers with alcoholic hepatitis and/or cirrhosis as compared to subjects without liver injury or with steatosis only [46, 56]. Lymphocyte-rich infiltrates are detectable in about 40% of ALD patients and their presence correlates with the extension of intralobular inflammation, peace-meal necrosis, and septal fibrosis [14]. Liver infiltrating T-lymphocytes in both ALD patients and alcohol-consuming rodents express markers associated with the activation/memory phenotypes and have an increased capacity to secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines [4]. Consistently, heavy drinkers with lipid peroxidation-derived antibodies have a fivefold higher prevalence of elevated plasma TNF-α levels than alcohol abusers with these antibodies within the control range [80]. Moreover, in these subjects the combination of high TNF-α and lipid peroxidation-induced antibodies increases by 11-fold the risk of developing advanced ALD [80]. Altogether, these findings are consistent with a possible contribution of oxidative stress-driven immunity in sustaining hepatic inflammation in ALD. Interestingly, the elevation of the antibodies against lipid peroxidation-derived adducts is also an independent predictor of advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis in alcohol-consuming patients with CHC [81].

In conclusion, growing evidence indicates that alcohol-induced oxidative modifications of hepatic constituents trigger specific immune responses and, in combination with genetic predisposition, lead the breaking of the self-tolerance in the liver. The development of such adaptive immune responses is likely favored the alcohol-mediated stimulation of innate immunity and, on its turn, may contribute to maintain hepatic inflammation during the evolution of ALD. Nonetheless, in the progression of ALD to cirrhosis alcohol interactions with both the innate and adaptive immune systems are likely more complex. Indeed, recent reports indicate that chronic alcohol intake can promote fibrosis by interfering with the capacity of liver NK cells to selectively control the proliferation of early activated stellate cells [22, 26], whereas liver CD8+ T-lymphocytes participate to the pro-fibrogenic activation of stellate cells [61].

Prospective clinical studies are required to dissect out the precise role of immune responses in the progression of ALD. If supported by other studies, the concept that acquired immunity is involved in alcohol hepatotoxicity might lead to the development of simple immunometric assays to discriminate ALD patients at risk of progressing to hepatitis and/or fibrosis. Moreover, the identification of alcohol abusers with a prominent immune component in their hepatic disease might lead to a targeted use of immune-suppressive therapy in ALD.

References

Albano E, Clot P, Morimoto M, Tomasi T, Ingelman-Sundberg M, French S (1996) Role of cytochrome P4502E1-dependent formation of hydroxyethyl free radicals in the development of liver damage in rats intragastrically fed with ethanol. Hepatology 23:155–163

Albano E, French SW, Ingelman-Sundberg M (1999) Hydroxyethyl radicals in ethanol hepatotoxicity. Front Biosci 4:533–540

Albano E (2006) Alcohol, oxidative stress and free radical damage. Proc Nutr Soc 65:278–290

Batey RG, Cao Q, Gould B (2002) Lymphocyte-mediated liver injury in alcohol-related hepatitis. Alcohol 27:37–41

Bautista AP (2002) Neutrophilic infiltration in alcoholic hepatitis. Alcohol 7:17–21

Bettelli E, Korn T, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK (2008) Induction and effector functions of Th17 cells. Nature 493:1051–1057

Biron C, Lalloyer N, Tonnelot JL, Gris JC, Schved JF (1995) Anticardiolipin antibodies and acute alcoholic intoxication. Lupus 4:486–490

Chang MK, Binder CJ, Miller YI, Subbanagounder G, Silverman GJ, Berliner JA, Witztum JL (2004) Apoptotic cells with oxidation-specific epitopes are immunogenic and proinflammatory. J Exp Med 11:1359–1370

Chedid A, Mendenhall CL, Moritz TE, French SA, Chen TS, Morgan TR, Rosselle GA, Nemchausky BA, Taburro CH, Schiff ER, McClain GJ, Marsano LS, Allen JI, Samanta A, Weesner RE, Henderson WG, Veteran Affairs Cooperative Group 275 (1993) Cell-mediated hepatic injury in alcoholic liver disease. Gastroenterology 105:254–266

Chedid A, Chadalawada KR, Morgan TR, Moritz TE, Mendenhall CL, Hammond JB, Emblad PW, Cifuentes DC, Kwak JWH, Gilman-Sachs A, Beaman KD (1994) Phospholipid antibodies in alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 20:1465–1471

Clot P, Bellomo G, Tabone M, Aricò S, Albano E (1995) Detection of antibodies against proteins modified by hydroxyethyl free radicals in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 108:201–207

Clot P, Albano E, Elliasson E, Tabone M, Aricò S, Israel Y, Moncada Y, Ingelman-Sundberg M (1996) Cytochrome P4502E1 hydroxyethyl radical adducts as the major antigenic determinant for autoantibody formation among alcoholics. Gastroenterology 111:206–216

Choi J, Ou JHJ (2006) Mechanisms of liver injury III. Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of hepatitis C virus. Am J Physiol 290:G847–G851

Colombat M, Charlotte F, Ratziu V, Poyard T (2002) Portal lymphocytic infiltrate in alcoholic liver disease. Hum Pathol 33:1170–1174

Chou MY, Hartvigsen K, Hansen LF, Fogelstrand L, Shaw PX, Boullier A, Binder CJ, Witztum JL (2008) Oxidation-specific epitopes are important targets of innate immunity. J Intern Med 263:479–488

Egen JG, Kuhns MS, Allison JP (2002) CTLA-4: new insights into its biological function and use in tumor immunotherapy. Nat Immunol 3:611–618

Gough SC, Walker LS, Sansom DM (2005) CTLA4 gene polymorphism and autoimmunity. Immunol Rev 204:102–115

Göran HK, Libby P (2006) Immune response in atherosclerosis: a double-edged sword. Nat Rev Immunol 6:508–519

Hines IN, Wheeler MD (2004) Recent advances in alcoholic liver disease III. Role of the innate immune response in alcoholic hepatitis. Am J Physiol 287:G310–G314

Horiguchi N, Wang L, Mukhopadhyay P, Park O, Jeong WI, Lafdil F, Osei-Hyiaman D, Moh A, Fu XY, Pacher P, Kunos G, Gao B (2008) Cell type-dependent pro-and anti-inflammatory role of signal transducer activator of transcription 3 in alcoholic liver injury. Gastroenterology 134:1148–1158

Huang H, Park PH, McMullen MR, Nagy LE (2008) Mechanisms for the anti-inflammatory effects of adiponectin in macrophages. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 23(suppl. 1):S50–S53

Gao B, Radaeva S, Jeong W (2007) Activation of NK cells inhibits liver fibrosis: a novel strategy to treat fibrosis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 1:173–180

George J (2008) Mechanisms of disease: the evolving role of regulatory T cells in atherosclerosis. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med 5:531–540

Gustot T, Lemmers A, Moreno C, Nagy N, Quertinmont E, Nicaise C, Franchimont D, Louis H, Devière J, Le Moine O (2006) Differential liver sensitization to toll-like receptor pathway in mice with alcoholic fatty liver. Hepatology 43:989–1000

Israel Y, Hurwitz E, Niemelä O, Arnon R (1986) Monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies against acetaldehyde-containing epitopes in acetaldehyde-protein adducts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 83:7923–7927

Jeong W, Park O, Gao B (2008) Abrogation of anti-fibrotic effects of NK/INF-γ contributes to alcohol acceleration of liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology 134:248–258

Kagan VE, Borisenko GG, Serinkan BF, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Jiang J, Liu SX, Shvedova AA, Fabisial JP, Uthsaisang W, Fadeel B (2003) Appetizing rancidity of apoptotic cells for macrophages: oxidation, externalization and recognition of phosphatidylserine. Am J Physiol 285:L1–L17

Kang L, Sebastian BM, Pritchard MT, Pratt BT, Previs SF, Nagy LE (2007) Chronic ethanol-induced insulin resistance is associated with macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue and altered expression of adiponectin. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 31:1581–1588

Klassen LW, Tuma D, Sorrell MF (1995) Immune mechanisms of alcohol-induced liver disease. Hepatology 22:355–357

Koskinas J, Kenna JG, Bird GL, Alexander GJM, Williams R (1992) Immunoglobulin A antibody to a 200-kilodalton cytosolic acetaldehyde adduct in alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 103:1860–1867

Krysko DV, D’Herde K, Vandenabeele P (2006) Clearance of apoptotic and necrotic cells and its immunological consequences. Apoptosis 11:1709–1726

Kurien BT, Scofield RH (2008) Autoimmunity and oxidatively modified antigens. Autoimmun Rev 7:567–573

Lago F, Dieguez C, Gomez-Reino J, Gualillo O (2007) Adipokines as emerging mediators of immune response and inflammation. Nat Rev Clin Pract Rheumatol 3:716–724

Laskin CA, Vidinis E, Blendis LM, Soloninka CA (1990) Autoantibodies in alcoholic liver disease. Am J Med 89:129–133

Laso JF, Madruga IJ, Orfao A (2002) Cytokines and alcohol liver disease. In: Sherman CDIN, Preedy VR, Watson RR (eds) Ethanol and the liver. Taylor and Francis, London, pp 206–219

Lavala J, Vietala J, Koivisto H, Jarvi K, Anttila P, Niemela O (2005) Immune responses to ethanol metabolites and cytokine profiles differentiate alcoholics with or without liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol 100:1303–1310

Lemmers A, Moreno C, Gustot T, Maréchal R, Degreé D, Demetter P, de Nadal P, Geerts A, Quertinmont E, Vercruysse V, Le Moine O, Devière J (2009) The interleukin-17 pathway is involved in human alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 49:646–657

Lytton SD, Hellander A, Zhang-Gouillon ZQ, Stokkeland K, Bordone R, Aricò S, Albano E, French SW, Ingelman-Sundberg M (1999) Autoantibodies against cytochromes P-4502E1 and P4503A in alcoholics. Mol Pharmacol 55:223–233

Ma X, Hua J, Mohamood AR, Hamad AR, Ravi R, Li Z (2007) A high-fat diet and regulatory T cells influence susceptibility to endotoxin-induced liver injury. Hepatology 46:1519–1529

Mandrekar P, Szabo G (2009) Signalling pathways in alcohol-induced liver inflammation. J Hepatol 50:1258–1266

McFarlane IG (2000) Autoantibodies in alcoholic liver disease. Addict Res 5:141–151

McMullen MR, Pritchard MT, Wang Q, Millward CA, Croniger CM, Nagy LE (2005) Early growth response-1 transcription factor is essential for ethanol-induced fatty liver in mice. Gastroenterology 128:2066–2076

McVicker BL, Tuma DJ, Kubik JA, Hindemith AM, Baldwin CR, Casey CA (2002) The effect of ethanol on asialoglycoprotein receptor-mediated phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by rat hepatocytes. Hepatology 36:1478–1487

Minagawa M, Deng Q, Liu ZX, Tzukamoto H, Dennert G (2004) Activated natural killer T cells induce liver injury by Fas and tumor necrosis factor-α during alcohol consumption. Gastroenterology 126:1387–1399

Moncada C, Torres V, Vargese E, Albano E, Israel Y (1994) Ethanol-derived immunoreactive species formed by free radical mechanisms. Mol Pharmacol 46:786–791

Mottaran E, Stewart SF, Rolla R, Vay D, Cipriani V, Moretti MG, Vidali M, Sartori M, Rigamonti C, Day CP, Albano E (2002) Lipid peroxidation contributes to immune reactions associated with alcoholic liver disease. Free Radic Biol Med 32:38–45

Nagy LE (2003) Recent insights into the role of the innate immune system in the development of alcoholic liver disease. Exp Biol Med 228:882–890

Natori S, Rust C, Stadheim LM, Srinivasan A, Burgan LJ, Gores GJ (2001) Hepatocyte apoptosis is a pathological feature of human alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol 24:248–253

Naveau S, Perlemuter G, Chaillet M, Raynard B, Balian A, Beuzen F, Portier A, Galanaud P, Emilie D, Chaput JC (2006) Serum leptin in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 30:1422–1428

Niemelä O, Klajner F, Orrego H, Vidinis E, Blendis L, Israel Y (1987) Antibodies against acetaldehyde-modified protein epitopes in human alcoholics. Hepatology 7:1210–1214

Palinski W, Witztum JL (2000) Immune response to oxidative neoepitopes on LDL and phospholipids modulate the development of atherosclerosis. J Intern Med 247:171–180

Paronetto F (1993) Immunologic reactions in alcoholic liver disease. Semin Liver Dis 13:183–195

Ouyang W, Kolls JK, Zheng Y (2008) The biological functions of T helper 17 cell effector cytokines in inflammation. Immunity 28:454–467

Rao R (2009) Endotoxemia and gut barrier dysfunction in alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 50:638–644

Rigamonti C, Mottaran E, Reale E, Rolla R, Cipriani V, Capelli F, Boldorini R, Vidali M, Sartori M, Albano E (2003) Moderate alcohol consumption increases oxidative stress in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 38:42–49

Rolla R, Vay D, Mottaran E, Parodi M, Sartori M, Rigamonti C, Bellomo G, Albano E (2001) Anti-phospholipid antibodies associated with alcoholic liver disease specifically recognize oxidized phospholipids. Gut 49:852–859

Rolla R, Vay D, Mottaran E, Parodi M, Traverso N, Aricò S, Sartori M, Bellomo G, Klassen LW, Thiele GM, Tuma DJ, Albano E (2000) Detection of circulating antibodies against malondialdehyde-acetaldehyde adducts in patients with alcohol-induced liver disease. Hepatology 31:878–884

Ronis MJJ, Butura A, Sampey BP, Prior RL, Korourian S, Albano E, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Petersen DR, Badger TM (2005) Effects of N-acetyl cysteine on ethanol-induced hepatotoxicity in rats fed via total enteral nutrition. Free Radic Biol Med 39:619–630

Ronis MJ, Butura A, Korourian S, Shankar K, Simpson P, Badeaux J, Albano E, Ingelman-Sundberg M, Badger TM (2008) Cytokine and chemokine expression associated with steatohepatitis and hepatocyte proliferation in rats fed ethanol via total enteral nutrition. Exp Biol Med 233:344–355

Ramaiah SH, Ritting S (2007) Role of osteopontin in regulating hepatic inflammatory responses and toxic liver injury. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 3:519–526

Safadi R, Ohta M, Alvarez CE, Fiel MI, Bansal M, Mehal WZ, Friedman SL (2004) Immune stimulation of hepatic fibrogenesis by CD8 cells and attenuation by transgenic interleukin-10 from hepatocytes. Gastroenterology 127:870–882

Savill J, Dransfield I, Gregory C, Haslett C (2002) A blast from the past: clearance of apoptotic cells regulates immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 2:965–975

Schneiderhan W, Schmid-Kotsas A, Zhao J, Grunert A, Nusslaer A, Weidenbach H, Menke A, Schmid RM, Adler G, Bachem MG (2001) Oxidized low-density lipoproteins bind to the scavenger receptor, CD36, of hepatic stellate cells and stimulate extracellular matrix synthesis. Hepatology 34:729–737

Seth D, Gorrell MD, Cordoba S, McCaughan GW, Haber PS (2006) Intrahepatic gene expression in human alcoholic hepatitis. J Hepatol 45:306–320

Song K, Coleman RA, Zhu X, Alber C, Ballas ZK, Waldschmidt TJ, Cook RT (2002) Chronic ethanol consumption by mice results in activated splenic T cells. J Leukoc Biol 72:1109–1116

Song K, Coleman RA, Alber C, Ballas ZK, Waldschmidt TJ, Mortari F, LaBrecque DR, Cook RT (2001) TH1 cytokine response of CD57+ T-cell subsets in healthy controls and patients with alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol 24:155–167

Song Z, Zhou Z, Deaciuc I, Chen T, McClain CJ (2008) Inhibition of adiponectin production by homocysteine: a potential mechanism for alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 47:867–879

Stewart SF, Vidali M, Day CP, Albano E, Jones DEJ (2004) Oxidative stress as a trigger for cellular immune response in patients with alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 39:197–203

Szabo G, Mandrekar P (2009) A recent perspective on alcohol, immunity and host defence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 33:220–232

Takase S, Tsutsumi M, Kawahara H, Takada N, Takada A (1993) The alcohol-altered liver membrane antibody and hepatitis C virus infection in the progression of alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 17:9–13

Thakur V, Pritchard MT, McMullen MR, Wang Q, Nagy LE (2006) Chronic ethanol feeding increases activation of NADPH oxidase by liposaccharide in rat Kupffer cells: role of increased reactive oxygen in LPS-stimulated ERK1/2 activation and TNF-alpha production. J Leukoc Biol 79:1348–1356

Thiele GM, Freeman TK, Klassen LW (2004) Immunological mechanisms of alcoholic liver disease. Semin Liver Dis 24:273–287

Tesmer LA, Lundy SK, Sarkar S, Fox DA (2008) Th17 cells in human disease. Immunol Res 223:87–113

Tilg H, Moschen AR (2006) Adipokines: mediators linking adipose tissue, inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol 6:4772–4783

Van Pelt FNAM, Straub P, Manns MP (1995) Molecular basis of drug-induced immunological liver injury. Semin Liver Dis 15:283–300

Vay D, Rigamonti C, Vidali M, Mottaran E, Alchera E, Occhino G, Sartori M, Albano E (2006) Anti-phospholipid antibodies associated with alcoholic liver disease target oxidized phosphatidylserine on apoptotic cell plasma membranes. J Hepatol 44:183–189

Vidali M, Stewart SF, Rolla R, Daly AK, Chen Y, Mottaran E, Jones DEJ, Leathart JB, Day CP, Albano E (2003) Genetic and epigenetic factors in autoimmune reactions toward cytochrome P4502E1 in alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology 37:277–285

Vidali M, Hidestrand M, Eliasson E, Mottaran E, Reale E, Rolla R, Occhino G, Albano E, Ingelman-Sundberg M (2004) Use of molecular simulation for mapping conformational CYP2E1 epitopes. J Biol Chem 279:50949–50955

Vidali M, Stewart SF, Albano E (2008) Interplay between oxidative stress and immunity in the progression of alcohol-mediated liver injury. Trends Mol Med 14:63–71

Vidali M, Hietala J, Occhino G, Ivaldi A, Sutti S, Niemelä O, Albano E (2008) Immune responses against oxidative stress-derived antigens are associated with increased circulating Tumor Necrosis Factor-α and accelerated liver damage in heavy drinkers. Free Radic Biol Med 45:306–311

Vidali M, Occhino G, Ivaldi A, Rigamonti C, Sartori M, Albano E (2008) Combination of oxidative stress and steatosis is a risk factor for fibrosis in alcohol-drinking patients with chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol 103:147–153

Winau F, Quack C, Darmoise A, Kaufmann SH (2008) Starring stellate cells in liver immunology. Curr Opin Immunol 20:68–74

Yip WW, Burt AD (2006) Alcoholic liver disease. Semin Diagn Pathol 23:149–160

Yokoyama H, Ishii H, Nagata S, Kato S, Kamegaya K, Tsuchiya M (1993) Experimental hepatitis induced by ethanol after immunization with acetaldehyde adducts. Hepatology 17:14–19

Acknowledgments

The author’s researches have been supported by grants from the Regional Government of Piedmont (Ricerca Sanitaria Finalizzata 2002, 2004 and Ricerca Scientifica Applicata 2004).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no competing interests on the matter concerning the present manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Albano, E., Vidali, M. Immune mechanisms in alcoholic liver disease. Genes Nutr 5, 141–147 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12263-009-0151-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12263-009-0151-4