Abstract

Patients with previous abdominal surgery are at an increased risk of peritoneal adhesions, which may complicate transperitoneal surgery. The objective of this article is to report single centre experience with transperitoneal laparoscopic and robotic partial nephrectomy for renal cancer in patients with previous abdominal surgery. We evaluated data from 128 patients who underwent laparoscopic or robotic partial nephrectomy from January 2010 to May 2020. Patients were divided into three groups according to the localization of main previous surgery: in the upper contralateral abdominal quadrant, in the upper ipsilateral abdominal quadrant or in the middle line, in lower abdominal quadrants. Each group was divided into two subgroups (laparoscopic/robotic partial nephrectomy). We separately analysed data of indocyanine green-enhanced robotic partial nephrectomy. Our study did not find significant difference in the rate of intraoperative or postoperative complications between any of the groups. The type of partial nephrectomy (robotic or laparoscopic) affected the surgery time, blood loss, and length of stay in hospital, but did not significantly influence the frequency of complications. Partial nephrectomy in group of patients with prior renal surgery led to a higher rate of intraoperative low-grade complications. We did not observe more favourable results for indocyanine green-enhanced robotic partial nephrectomy. The location of previous abdominal surgery does not influence the rate of intraoperative or postoperative complications. The type of partial nephrectomy (robotic or laparoscopic) does not affect the frequency of complications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Patients with a history of previous abdominal surgery are at possible risk of perioperative complications during subsequent surgical procedures [1, 2]. Previous groups have reported the effects of previous abdominal surgery on transperitoneal laparoscopic or robotic urologic procedures including surgical treatment for renal cancer with variable results [1,2,3]. The aim of our work is to provide an extensive and complex view of outcomes and complications for both laparoscopic and robotic transperitoneal partial nephrectomies, and to identify which subgroup has the highest possibility for developing intraoperative or postoperative complications. We evaluated perioperative statistics and postoperative results of partial nephrectomies in patients with a history of previous renal surgery and in patients with a history of previous non-renal surgery separately.

Modern digital visualisation technologies have facilitated the usage of perioperative navigation and imaging in order to achieve more favorable functional results during surgery. One common method of perioperative imaging is near-infrared fluorescence with indocyanine green (ICG), based on the standard principle of fluorescence, as described well in the literature [4]. ICG permits the surgeon to perform perioperative angiography with precise vascularity visualisation, imaging of anatomical features of tissues, and lymphography with ICG-navigated sentinel lymph node mapping [5]. Our centre is focused on the principle of ICG-angiography during robotic partial nephrectomy, which enables selective clamping of the segmental renal artery or superselective clamping of the tumour-supplying artery. Thus, we separately introduce and evaluate outcomes and complications in patients with previous abdominal surgery who underwent robotic partial nephrectomy enhanced by ICG usage.

Patients and Methods

Patients

We retrospectively evaluated data of 219 patients who underwent laparoscopic or robotic partial nephrectomy in our centre from January 2010 to May 2020. We have chosen for the end of data evaluation period the beginning of COVID-19 disease in our country, which significantly affected surgical performance in our department. We identified 128 patients who had at least one previous abdominal surgery in their personal history and who underwent laparoscopic or robotic partial nephrectomy for a renal tumour. A total of 28 patients underwent robotic surgery with the use of ICG (this fluorescent dye has been used in our centre since April 2015). One patient underwent a robotic partial nephrectomy using a retroperitoneal approach, and was not included in the study. The data are analysed with delay due to COVID-19 pandemic and restrictions.

Data and Statistical Analysis

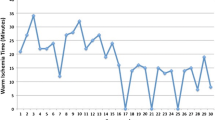

The patients were divided into three groups according to the localization and type of previous surgery and its proximity to the site of the partial nephrectomy: (A) patients with a main previous surgery in the upper contralateral abdominal quadrant, (B) patients with a main surgery in the upper ipsilateral abdominal quadrant or in the middle line, (C) patients with a main previous surgery in lower abdominal quadrants. Each group was divided into two subgroups according to the type of partial nephrectomy (laparoscopic/robotic), and intraoperative and postoperative outcomes were analysed separately. A total of 57% patients had undergone one previous abdominal surgery, while 43% had undergone two or more previous surgeries. In cases with multiple surgeries in the personal history, we considered the prior surgery located at the shortest distance to the field of planned partial nephrectomy as definitive for dividing the patients into the respective groups. We separately evaluated outcomes and intraoperative and postoperative complications of ICG-enhanced partial nephrectomies. Intraoperative and postoperative outcomes of patients with a history of previous renal surgery and patients with a history of previous non-renal surgery were evaluated separately as well. In all groups, we recorded mean age, body mass index (BMI), Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) and tumour diameter. We evaluated mean surgery time, warm ischemia time, blood loss, length of hospital stay, positive surgical margins, intraoperative and postoperative complications, preoperative and postoperative creatinine value. Intraoperative and postoperative complications were evaluated according to Clavien-Dindo (CD) classification of surgical complications [6]. Variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and median (range). The mean values were compared using the Student’s t-test. All test were performed in STATISTICA, version 12, Statsoft Inc, Tulsa, CA. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

Surgical Technique

Laparoscopic partial nephrectomy was started by placing the patient on the contralateral side position. A pneumoperitoneum was created via a Veress needle, inserted into non-scarred skin, and the abdominal cavity was insufflated to 13 mmHg. Then, a camera port (12 mm) was inserted through the incision. If the pneumoperitoneum could not be created by the Veress needle, the Hasson technique was used for insertion of the camera port [7]. Two ports for laparoscopic instruments (5 mm, 12 mm) were placed in the medioclavicular line. Adhesiolysis of recognised adhesions (Fig. 1) was performed with laparoscopic scissors. Complete exophytic renal tumours were dissected without hilar arterial clamping, endophytic renal tumours were dissected with non-selective, selective or superselective clamping according to the current renal vascular anatomy. Renal calices were repaired if damaged, a running suture ensured by hem-o-lock clips over the resection bed was done to stop bleeding and to attach the margins of resection. A bag was used for tumour extraction, pneumoperitoneum was evacuated, fascial defects were closed and the skin was resutured. Robotic partial nephrectomies were performed by daVinci Standard® surgical system until November 2013, since then by daVinci SI HD® system with near-infrared fluorescence imaging mode using a 12-mm robotic camera port, two 8-mm robotic ports and an additional 12-mm port. Renal tumours were dissected with purely off-clamp technique in cases of completely exophytic growth of tumour. The renal hilus was exposed prior to renal tumour dissection in setting of non-fully exophytic growth of tumour and on-clamp technique of partial nephrectomy was performed. In cases of unfavourable anatomical settings, the non-selective clamping of renal hilus was performed or the ICG fluorescent dye was used. Next steps of robotic partial nephrectomy (excluding renorrhaphy, which was performed with the sliding clip technique) were similar to the steps of laparoscopic partial nephrectomy, described above. In 28 cases, ICG was used for intraoperative angiography to visualise the renal tumour blood supply, administration was performed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, as we recently described [8].

Results

Analysis of patient characteristics showed significantly lower mean R.E.N.A.L. nephrometry score (6 vs. 7) in the group of patients who underwent laparoscopic partial nephrectomy compared to the group of patients with robotic partial nephrectomy, no significant differences were found for any other observed parameters (Table 1). We identified 27 patients (14%) with previous abdominal surgery in the upper contralateral quadrant, 63 patients (32%) with previous surgery in the upper ipsilateral quadrant and 106 patients (54%) with previous surgery in lower abdominal quadrants (Table 2). Group A included 21 patients with previous abdominal surgery in the upper contralateral quadrant. Of all 21 cases, 8 patients underwent laparoscopic partial nephrectomy and 13 patients robotic partial nephrectomy. These subgroups were similar in mean age (60 vs. 55 years), mean BMI (29.9 vs. 28.0 kg/m2), mean CCI (5 vs. 4) and mean average tumour diameter (26 vs. 22 mm). Significantly shorter mean surgery time (100 vs. 125 min), higher mean blood loss (238 vs. 93 mL) and lower mean preoperative glomerular filtration rate were observed in the laparoscopic subgroup. No significant differences were found in any other studied parameters. Group B contained 60 patients with previous abdominal surgery in the upper ipsilateral quadrant or in the middle line. A total of 22 patients underwent laparoscopic partial nephrectomy and 38 patients underwent robotic partial nephrectomy; the subgroups were similar in mean age (64 vs. 65 years), mean BMI (28.9 vs. 29.7 kg/m2), mean CCI (4 vs. 5) and mean average tumour diameter (22 vs. 26 mm). In total, 3 patients (14%) in the laparoscopic subgroup and 3 patients (8%) in robotic subgroups were discharged with significantly elevated values of creatinine compared to preoperative values. No significant differences between these subgroups were found in any of the observed parameters. Group C included 47 patients with previous abdominal surgery in lower abdominal quadrants; 11 patients underwent laparoscopic partial nephrectomy and 36 patients underwent robotic partial nephrectomy. Subgroups were similar in mean age (55 vs. 59 years), mean BMI (26.9 vs. 27.5 kg/m2), mean CCI (3 vs. 4) and mean average tumour diameter (34 vs. 32 mm). Significantly, shorter mean surgery time (107 vs. 130 min) and longer average length of stay in hospital (9 vs. 7 days) were observed in the laparoscopic subgroup. No significant differences were found in any of the other parameters. The type of partial nephrectomy (robotic or laparoscopic) did not significantly influence the frequency of intraoperative or postoperative complications in any of our patient groups (Table 3).

Intraoperative and postoperative complications were evaluated separately for each studied group according to Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications. Grades I and II were stratified as low-grade complications; grades III, IV and V were stratified as high-grade complications. All complications were divided into intraoperative complications and early postoperative complications, which occurred within 30 days, and they were evaluated for each studied group separately. Intraoperative low-grade complications were observed in 2 cases (1.6 %) and were defined as excessive bleeding of the tumour bed with blood transfusion - 1 case in group B and 1 case in group C. Intraoperative high-grade complications were recorded in a total of 6 cases (4.7%), and included vessel injury (3 cases, 2.3%), intestine injury (2 cases, 1.6%) and diaphragm injury (1 case, 0.8%), all with need of suture. A total of 3 cases were observed in group B and 3 cases in group C. Postoperative low-grade complications were identified in 18 cases (14.1%), and included urinary tract infections with the necessity of the antimicrobial therapy (8 cases, 6.3%), perirenal hematoma with the need for blood transfusion without surgical intervention (5 cases, 3.9%), paralytic ileus managed by drug therapy (4 cases, 3.1%) and infection in the surgical wound managed at the bedside (1 case, 0.8%). In summary, 2 cases were recorded in group A, 10 cases in group B and 6 cases in group C. Postoperative high-grade complications were found in 4 cases (3.1%): a renal artery aneurysm with the need for radiological endovascular embolization (1 case, 0.8%), urinoma from the insufficient suture of the renal calyx with the necessity for urine drainage (1 case, 0.8%), urine retention with the need for surgical intervention (1 case, 0.8%) and renal and respiratory failure with the need for oxygen therapy and intensive care unit treatment (1 case, 0.8%) - 3 cases were found in group B and 1 case was observed in group C. After statistical analysis, we did not find any significant differences of frequency in any category of complications between the studied groups. The location of previous abdominal surgery in the upper contralateral quadrant, the upper ipsilateral quadrant (or in the middle line) or the lower abdominal quadrants did not significantly influence the rate of intraoperative or postoperative complications.

We analysed characteristics and results of 29 patients with a history of previous surgery on ipsilateral/contralateral kidney and 99 patients with previous non-renal surgery who underwent transperitoneal partial nephrectomy. Significant differences were observed in patient sex stratification, mean CCI (5 vs. 4), longer mean surgery time (132 vs. 116 min), higher intraoperative low-grade complications (2 vs. 0), higher mean postoperative creatinine (113 vs. 78) and lower mean postoperative glomerular filtration rate in group of patients with prior renal surgery. No significant differences were found in any of the other observed parameters (Table 4).

We separately evaluated outcomes and complications of 28 patients with previous abdominal surgery who underwent robotic partial nephrectomy enhanced by ICG, and compared them to outcomes of 59 patients who underwent robotic partial nephrectomy without ICG imaging. These subgroups were similar in mean age (58 vs. 62 years), mean BMI (29.7 vs. 28.0 kg/m2), mean CCI (4 vs. 5), and in mean R.E.N.A.L. score (7 vs. 6). Significant differences were observed in higher mean CT tumour diameter (32 vs. 26 mm) and in higher intraoperative low-grade complications (2 vs. 0) in group of patients with use of ICG. No significant differences were found in all other observed parameters. Of 28 cases, the application of ICG helped to track a specific tumour-supplying artery in 19 cases where superselective clamping was performed, while 7 partial nephrectomies were completed with non-selective clamping of the renal artery. Our study did not find better intraoperative outcomes or a lower frequency of complications in cases where partial nephrectomy was enhanced by ICG imaging in the group of patients with previous abdominal surgery (Table 5).

Discussion

Minimally invasive partial nephrectomy is considered to be a standard method of therapy of localised renal cancer, with superior long-term postoperative outcomes compared to radical nephrectomy. Laparoscopic and robotic partial nephrectomy offer more favourable intraoperative outcomes and better postoperative outcome compared to open techniques. Moreover, robotic surgical systems have enabled surgeons to overcome the technical limits of laparoscopy [9, 10].

Peritoneal adhesions after abdominal and pelvic surgeries remain extremely common. The formation of postsurgical adhesions has been reported to occur in up to 90% of patients with a history of previous abdominal surgery. There are several aspects that contribute to these adhesions: location, type and extension of previous surgery, presence of suture material, persistence of haematoma, preoperative/postoperative infections and influence of electrocautery [11]. Other potential causes of adhesions, such as radiation therapy and inflammatory disorders, were not considered in this study. Peritoneal adhesions, caused by previous surgery can be accompanied by incisional hernias, which can also complicate or worsen the results of the subsequent surgery (Fig. 2).

Previous groups have reported the effects of previous abdominal surgery on transperitoneal laparoscopic urologic procedures with variable results [2, 12, 13]. Several researchers have published the impact of previous surgeries on transperitoneal robotic surgery [1, 3, 14]. While some authors consider patients with a previous inguinal hernia surgery as a part of group with prior abdominal surgery in common [14], other authors published outcomes of 321 patients who underwent transperitoneal robotic partial nephrectomy and they did not include inguinal hernia surgery in their group of previous abdominal surgeries [1]. In our study, we considered intraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair and umbilical hernia repairs as a part of group of previous abdominal surgeries, while extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repairs were excluded. Entry techniques in laparoscopic surgery via a Veress needle can be associated with increased rates of failed entry and visceral injury. A rate of access complications of 4% for patients undergoing renal/adrenal laparoscopic procedures via the transperitoneal approach is described in literature [15]. We did not record any complications creating a pneumoperitoneum via a Veress needle in our group of patients and an open technique was used minimally. Location of entry to peritoneal cavity was modified in cases of large abdominal scars (Fig. 3) with the aim of avoiding the access through the scarred skin.

Several groups have reported the impacts of previous abdominal surgery on different urologic robotic surgeries. One study published outcomes of robotic radical prostatectomies in patients with a history of previous abdominal surgery and showed no increased risk of complications [16]. In contrast, another study described results from 18 patients undergoing robot-assisted radical cystectomy, who had a higher risk for postoperative complications [17]. The impacts of previous abdominal surgery on transperitoneal laparoscopic procedures have also been evaluated [2, 12, 13, 15]. Some authors have described higher complication rates in patients with prior abdominal surgery [13], while others have shown no increase in complications [2, 15]. We identified one patient who underwent a retroperitoneal approach for robotic partial nephrectomy in our centre with favourable outcomes and no intraoperative or postoperative complications. We did not include this patient into our study. An extensive meta-analysis suggesting that retroperitoneal robotic partial nephrectomy appears to be equally safe and efficacious in terms of complications, conversion and oncologic control compared with transperitoneal robotic partial nephrectomy [18].

Urologic surgeons in our centre only use ICG during robotic partial nephrectomy. To facilitate this procedure, ICG can be used in three different ways. The first, which is demonstrated in our study, uses ICG to visualise of the vascular supply of the kidney. It enables the surgeon to recognise the branches of the main renal artery and perform a targeted closure of the blood flow to the relevant renal segment (selective clamping), or perform a targeted closure of the artery that supplies the tumour (superselective clamping) [19]. The second possibility takes advantage of the ability of ICG to form a chemical bond with the protein bilitranslocase (BLT), which is located in the proximal and distal renal tubules and serves as an intracellular transporter of the ICG molecule. A healthy renal parenchyma is capable of accumulating ICG molecules intracellularly and emits detectable fluorescent light. Renal tumour cells do not express BTL, ICG molecules are rapidly washed from the tumourous tissue and it does not emit fluorescent light. This imaging technique requires the administration of higher doses of ICG [5, 19]. The third method is usage of ICG as lipiodol-ICG mixture, administered intravenously before surgery and serving as a preoperative angiography agent. This angiographic mixture selectively reaches arteries of the tertiary order and enables the superselective labelling of tumour tissue. Lipiodol in the mixture counteracts the rapid reduction of ICG from tumourous tissue. The resection itself takes place without the restriction or interruption of arterial blood to the kidney [20].

Conclusion

The location of previous abdominal surgeries did not significantly influence the rate of intraoperative or postoperative complications of subsequent partial nephrectomy in our study. The type of partial nephrectomy (robotic or laparoscopic) affected surgery time, blood loss and the length of hospital stay, but did not significantly influence the frequency of complications. Extended surgery time and higher rate of intraoperative low-grade complications during partial nephrectomy were observed in the group of patients with previous renal surgery compared to the group of with previous non-renal surgery. Our study did not find more favourable intraoperative outcomes or a lower frequency of complications in cases where indocyanine green-enhanced partial nephrectomy was performed.

Data Availability

The dataset gathered during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zargar H, Isac W, Autorino R, Khalifeh A, Nemer O, Akca O et al (2015) Robot-assisted laparoscopic partial nephrectomy in patients with previous abdominal surgery: single center experience. Int J Med Robotics Comput Assist Surg 11(4):389–394

Parsons JK, Jarrett TJ, Chow GK, Kavoussi LR (2002) The effect of previous abdominal surgery on urological laparoscopy. J Urol 168(6):2387–2390

Nazemi T, Galich A, Smith L, Balaji KC (2006) Robotic urological surgery in patients with prior abdominal operations is not associated with increased complications. Int J Urol 13(3):248–251

Landsman ML, Kwant G, Mook GA, Zijlstra WG (1976) Lightabsorbing properties, stability, and spectral stabilization of indocyanine green. J Appl Physiol 40(4):575–583

Kaplan-Marans E, Fulla J, Tomer N, Bilal K, Palese M (2019) Indocyanine green (ICG) in urologic surgery. Urology 132:10–17

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA (2004) Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 240(2):205–213

Hasson HM (1971) A modified instrument and method for laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 110(6):886–887

Gadus L, Kocarek J, Chmelik F, Matejkova M, Heracek J (2020) Robotic partial nephrectomy with indocyanine green fluorescence navigation. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 2020:1287530

Huang WC, Elkin EB, Levey AS, Jang TL, Russo P (2009) Partial nephrectomy versus radical nephrectomy in patients with small renal tumors-is there a difference in mortality and cardiovascular outcomes? J Urol 181(1):55–61

Cacciamani GE, Medina LG, Gill T, Abreu A, Sotelo R, Artibani W et al (2018) Impact of surgical factors on robotic partial nephrectomy outcomes: comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol 200(2):258–274

Liakakos T, Thomakos N, Fine PM, Dervenis C, Young RL (2001) Peritoneal adhesions: etiology, pathophysiology, and clinical significance. Recent advances in prevention and management. Dig Surg 18(4):260–273

Soulie M, Salomon L, Seguin P, Mervant C, Mouly P, Hoznek et al (2001) Multi-institutional study of complications in 1085 laparoscopic urologic procedures. Urology 58(6):899–903

Chen RN, Moore RG, Cadeddu JA, Schulam P, Hedican SP, Llorens SA et al (1998) Laparoscopic renal surgery in patients at high risk for intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal scarring. J Endourol 12(2):143–147

Petros FG, Patel MN, Kheterpal E, Siddiqui S, Ross J, Bhandari A et al (2010) Robotic partial nephrectomy in the setting of prior abdominal surgery. Br J Urol Int 108(3):413–419

Seifman BD, Dunn RL, Wolf JS Jr (2003) Transperitoneal laparoscopy into the previously operated abdomen: effect on operative time, length of stay and complications. J Urol 169(1):36–40

Siddiqui SA, Krane LS, Bhandari A, Patel MN, Rogers CG, Stricker H et al (2010) The impact of previous inguinal or abdominal surgery on outcomes after robotic radical prostatectomy. Urology 75(5):1079–1082

Yuh BE, Ciccone J, Chandrasekhar R, Butt ZM, Wilding GE, Kim HL et al (2009) Impact of previous abdominal surgery on robot-assisted radical cystectomy. JSLS 13(3):398–405

Xia L, Zhang X, Wang X, Xu T, Qin L, Zhang X et al (2016) Transperitoneal versus retroperitoneal robot-assisted partial nephrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg 30:109–115

Ferroni MC, Sentell K, Abaza R (2018) Current role and indications for the use of indocyanine green in robot-assisted urologic surgery. Eur Urol Focus 4(5):648–651

Simone G, Tuderti G, Anceschi U, Ferriero M, Costantini M, Minisola F et al (2019) “Ride the green light”: indocyanine green-marked off-clamp robotic partial nephrectomy for totally endophytic renal masses. Eur Urol 75(6):1008–1014

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LG, JH: study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation; LG: literature search, manuscript writing; LG, FCH, MM, JH: performing surgeries; JH: final revision. All authors had full access to the data and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gadus, L., Chmelik, F., Matejkova, M. et al. Transperitoneal Laparoscopic and Robotic Partial Nephrectomy for Renal Cancer in Patients with Previous Abdominal Surgery: a Single Centre Experience. Indian J Surg 86, 73–81 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-023-03743-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-023-03743-x