Abstract

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy is an invasive procedure applied to large and complex stones in the prone or supine position. Various complications—but mostly fever or bleeding—can be seen during and after the procedure. Neighboring organ injuries are rare during access. Liver injuries are rarely seen and have a better clinical prognosis than other organ injuries. We present the management of liver injury with ptosis of the retro-renal right lobe as a complication during supine percutaneous nephrolithotomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) is accepted as the first choice in the treatment of complicated kidney stones with a long axis larger than 2 cm [1]. Liver injuries are extremely rare in both supine and prone variants of the PCNL [2]. This case report describes the successful conservative management of liver injury with a hemostatic sponge performed through a percutaneous nephrostomy tube (PNT).

Case Presentation

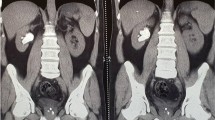

A 41-year-old male was admitted with right flank pain. Stones were diagnosed by computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). A supine PCNL was planned. Although the liver was observed to have a ptotic lobe and to extend to the right retro-renal area, a window partially distant to the liver, allowing lower pole access, was seen. Lower pole entry was made with a deep inspiration, biplanar method, in the supine position (Fig. 3). A 20-f Amplatz sheath was placed using Alken telescopic metal coaxial dilators. The stones were cleaned with miniaturized PCNL and ECIRS (Endoscopic Combined Intrarenal Surgery). An 18 F PNT was placed. No complications were detected. The patient’s hemoglobin (HB) value was 16 g/dl preoperatively, and 13.2 g/dl after surgery. The patient had stinging pain during respiration. The second HB value was 10 g/dl. CT, performed when epigastric pain arose, showed that the PNT passed the right lobe of the liver through the ptotic part. A 3-cm thick fluid collection was detected in the subdiaphragmatic and subhepatic areas (Fig. 4). After 2 units of erythrocyte suspension were transfused, the HB value was 11.6 g/dl, 12, and 13.1 g/dl, during the follow-up, increasingly, HB level remained stable, and the hematoma did not increase in the control ultrasonography (USG). Stinging pain and epigastric tenderness decreased. The PNT was retained for 10 days. On the 10th day, while the PNT was being removed, a guidewire was passed through it. This guidewire must have also passed through the ptotic lobe of the liver. An 18 F open-end smooth catheter was passed over the guide. A 70-mm long cylindrical piece of re-absorbable gelatin hemostatic sponge (Cutanplast Standart; Mascia Brunelli S.p.A., Milan, Italy) with a diameter of 10 mm was pushed through this catheter into the tract for hemostasis (Fig. 5). The patient was discharged after a further 1 day of follow-up, without HB change.

Ptotic part of the liver (yellow arrow) and the location of the right kidney stones in non-contrast CT. The complete CT is shown in the video (Online Resource 1)

PNT penetrating the lower lobe of the liver (blue arrow) and subhepatic hematoma (red arrow) in post-operative non-contrast CT. The complete CT is shown in the video (Online Resource 2)

Discussion

Although the most common injury during PCNL is in the pleura, the true incidence of pleural injury is not exactly known because it remains unnoticed in most of the cases as it is usually minor and of no clinical significance, with the incidence ranging between 0 and 12.5% [3]. The second most common injury is in the colon with an incidence of 0.5% [4]. Little is known about liver and spleen injuries. This could be because hepatic and splenic injuries are very rare and were not encountered even in large series [5]. Other reasons for underestimation may be poor documentation, or the injury may heal spontaneously without an obvious clinical presentation. In a study subjecting CTs performed after PCNL; thoracic complication (2.6%), colon perforation (0.2%), and spleen injury (0.2%), no liver injuries were observed [6]. As in the case, 1.20% of PCNL-related complications are grade IVa according to modified Clavien classification; liver injury has not been reported among them [7]. The highest risks are access above the 11th rib and hepatomegaly. Although the most preferred access for PCNL is subcostal, supracostal access is chosen to manage staghorn or complex upper pole stones. Supracostal entrances are open to adjacent organ injuries or intrathoracic complications [8]. A sagittal section abdominal CT study with 43 patients in forced respiration stated that the 12th rib is far from the liver and the 11th rib access brings 14% liver injury with it [9]. The current case was with subcostal access and had no hepatomegaly but the right lobe of the liver was ptotic into the retro-renal area. To avoid injuries due to hepatomegaly, USG- or CT-guided access is important. USG-guided entrances were defined targeting the correct calyx to avoid access complications [10].

Although PCNL was first applied in the prone position, the preference for the supine position is increasing day by day [11]. In a study comparing supine and prone intervention results, the supine position had less blood loss, shorter surgical time, and shorter hospital stay while stone-free and complication rates were equal [12]. Liver injury is not as serious as other intraperitoneal organ injuries. Unlike spleen and bowel injuries, it heals mostly conservatively, with close CT or USG follow-up. Exploration is recommended only in hemodynamically unstable patients [13]. In a study, in the case of liver injury after PCNL, the PNT was left for 5 days with conservative follow-up, and the tract was hemostasized with fibrin [14]. There is no common consensus as to when the PNT should be removed. It has been reported that it is safer to keep the PNT for 12–14 days in spleen injuries [15]. A study stated that ureteral double-J-stent and foley catheter placement is superior to prevent possible biloma after PNT removal [16]. In the current case, the PNT was removed on the 10th day after the regression of the hematoma in USG. Hemostasis was achieved by placing a sterile re-absorbable gelatin sponge with a hemostatic effect. The porous surface of the gelatin induces the rapid rupture of the blood plaques with the consequent activation of the enzymatic cascade, which leads to natural coagulation.

Conclusion

As in current case’s new technique, the injured tract can be filled with a hemostatic sponge while the PNT is being removed after PNT was held longer.

Change history

09 November 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-021-03152-y

References

Assimos D, Krambeck A, Miller NL, Monga M, Murad MH, Nelson CP et al (2016) Surgical management of stones: American Urological Association/Endourological Society Guideline PART I. J Urol 196(4):1153–1160

Falahatkar S, Mokhtari G, Teimoori M (2016) An update on supine versus prone percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a meta-analysis. Urol J 13(5):2814–2822

Sharma K, Sankhwar SN, Singh V, Singh BP, Dalela D, Sinha RJ et al (2016) Evaluation of factors predicting clinical pleural injury during percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a prospective study. Urolithiasis 44(3):263–270

Wu P, Wang L, Wang K (2011) Supine versus prone position in percutaneous nephrolithotomy for kidney calculi: a meta-analysis. Int Urol Nephrol 43(1):67–77

Michel MS, Trojan L, Rassweiler JJ (2007) Complications in percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Eur Urol. 51(4):899–906 (discussion)

Gnessin E, Mandeville JA, Handa SE, Lingeman JE (2012) The utility of noncontrast computed tomography in the prompt diagnosis of postoperative complications after percutaneous nephrolithotomy. J Endourol 26(4):347–350

Singh AK, Shukla PK, Khan SW, Rathee VS, Dwivedi US, Trivedi S (2018) Using the modified clavien grading system to classify complications of percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Curr Urol 11(2):79–84

Ozturk H (2014) Gastrointestinal system complications in percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a systematic review. J Endourol 28(11):1256–1267

Hopper KD, Yakes WF (1990) The posterior intercostal approach for percutaneous renal procedures: risk of puncturing the lung, spleen, and liver as determined by CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 154(1):115–117

Chu C, Masic S, Usawachintachit M, Hu W, Yang W, Stoller M et al (2016) Ultrasound-guided renal access for percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a description of three novel ultrasound-guided needle techniques. J Endourol 30(2):153–158

Proietti S, Rodriguez-Socarras ME, Eisner B, De Coninck V, Sofer M, Saitta G et al (2019) Supine percutaneous nephrolithotomy: tips and tricks. Transl Androl Urol 8(Suppl 4):S381–S388

Al-Dessoukey AA, Moussa AS, Abdelbary AM, Zayed A, Abdallah R, Elderwy AA et al (2014) Percutaneous nephrolithotomy in the oblique supine lithotomy position and prone position: a comparative study. J Endourol 28(9):1058–1063

Carrillo EH, Richardson JD (2001) The current management of hepatic trauma. Adv Surg 35:39–59

El-Nahas AR, Mansour AM, Ellaithy R, Abol-Enein H (2008) Case report: conservative treatment of liver injury during percutaneous nephrolithotomy. J Endourol 22(8):1649–1652

Schaeffer AJ, Handa SE, Lingeman JE, Matlaga BR (2008) Transsplenic percutaneous nephrolithotomy. J Endourol 22(11):2481–2484

Gadzhiev N, Malkhasyan V, Akopyan G, Petrov S, Jefferson F, Okhunov Z (2020) Percutaneous nephrolithotomy for staghorn calculi: troubleshooting and managing complications. Asian J Urol 7(2):139–148

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised due to a retrospective Open Access order.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1: Preoperative axial CT sections are viewed as moving from anterior to posterior (AVI 331831 KB)

Supplementary file2: Post-operative axial CT sections are viewed as moving from anterior to posterior (AVI 331831 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Üntan, İ., Sabur, V. Ptotic Right Retro-renal Liver Lobe Injury During Supine Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy Managed by Hemostatic Sponge. Indian J Surg 84, 555–558 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-021-03035-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-021-03035-2