Abstract

Peripheral venous cannulations are one of the most common procedures carried out in today’s healthcare setting. It is an invasive procedure and carries with it the risk of bloodstream infections. There are guidelines for insertion and management of peripheral venous cannulas. One such guideline is the standards of infusion therapy from the Royal College of Nursing. In this study, we aim to assess the process and outcomes of peripheral venous cannulation in our institution against these guidelines. We conducted a prospective completed audit loop study on the process and outcomes of peripheral venous cannulation in our institution. The preliminary audit was conducted in the month of December 2019. The staff were trained on various aspects of cannulation based on the guidelines in the following month. A reaudit was conducted between May and August 2020, and the data were analyzed. A total of 362 cannulations were audited for the study. Forty-seven cannulations were observed during the initial audit, and 315 cannulations were included for the reaudit. On comparative analysis, there was a statistically significant improvement in hand hygiene, use of gloves, appropriate site selection, flushing of the cannula, and documentation in the reaudit in comparison with the initial audit. There was also a statistically significant reduction in the number of recannulations. Peripheral intravenous cannulation although a simple procedure can cause significant morbidity if not performed properly. Auditing such procedures shows deficiencies in performance. Reaudit, after adequate retraining of staff, shows significant improvement in performance and outcome.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Peripheral venous cannulations are one of the most common procedures carried out in today’s healthcare setting. Almost all patients admitted to the inpatient ward have a cannula inserted. Its role in both diagnosis (injecting contrast for imaging) and treatment (securing venous access for hydration and drug administration) is well established [1]. Although it is a routinely carried out procedure, one must keep in mind that it is an invasive procedure and carries with it certain risks and complications. Complications include phlebitis, abscess, skin necrosis, and catheter-related bloodstream infections. They also play a major role in healthcare-associated infections (HAI) and hence can cause a significant impact on healthcare costs and hospital stay. There are guidelines set by various international bodies for the insertion, care, and management of a peripheral intravenous cannula to minimize complications associated with the procedure. One such guideline is from the Royal College of Nursing (RCN)-standards for infusion therapy [2]. Peripheral intravenous cannulation is often considered a nursing professional’s domain of expertise, but it cannot be stressed enough that every surgeon must be proficient enough to secure an intravenous line as it is the first line of management in many emergency conditions [3, 4].

In this study, we aim to assess the process and outcomes of peripheral venous cannulation in a tertiary care center against the RCN guidelines.

Patients and Methods

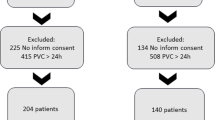

We conducted a prospective completed audit loop study on the process and outcomes of peripheral venous cannulation (PVC) in our institution against the guidelines set by the Royal College of Nursing (Table 1). The preliminary audit was conducted in the month of December 2019 by a single observer (first author). The process of cannulation was carried out by qualified nursing professionals and doctors working in our institution. We included cannulations which were performed both in the wards and in the emergency ward (Table 2). We prepared questionnaires based on the guidelines with yes or no options as the answers which were duly filled in after the procedure by the observer. The healthcare professionals performing the cannulation were not informed that they were being audited. The data was tabulated and analyzed. We then carried out a series of workshops and classes on how to perform a PVC for the healthcare professionals in our institution in the month of January 2020. Charts containing the guidelines were then put up in all the nursing stations in our institution. A reaudit was conducted from the month of May 2020 to August 2020 with four observers which now also included the nursing ward incharges and was carried out in a similar manner to the initial audit. The format of the audit was the same as the first audit done in December 2019. During the reaudit, all consecutive cannulations that took place in the hospital between 8 am and 5 pm during the study period were included.

Results

A total of 362 PVC procedures were audited for the study. Forty-seven procedures were audited during the initial audit, and 315 cannulations were included for the reaudit. The data was tabulated, and the results are given in Table 3.

In the initial audit, 44 cannulations were performed by nursing professionals while three cannulations were carried out by doctors. Seven cannulations were performed in the emergency ward and 40 cannulations in the wards. In the reaudit, 303 cannulations were performed by the nursing professionals while 12 cannulations were done by the doctors. Fifty-one cannulations were performed in the emergency ward while the remaining 264 were carried out in the wards. On comparative analysis, there was a statistically significant improvement with respect to hand hygiene, use of gloves, appropriate site selection, flushing of the cannula, and documentation in the reaudit in comparison with the initial audit. There was also a statistically significant reduction in the number of recannulations for the dislodgement of cannulas in the reaudit. Eight patients needed recannulation for phlebitis in our study, and all eight had a visual inflammatory phlebitis score of 1.

Discussion

Peripheral venous cannulation is one of the most common procedures carried out in the wards and can be associated with complications because of its invasive nature [1]. In our initial audit, we noticed poor compliance in hand hygiene, use of gloves, appropriate site selection, flushing of the cannula, and documentation. This may be attributed to the lack of knowledge and training regarding the standard guidelines. The reaudit showed improved compliance in all the previously mentioned steps which was also evident with a statistically significant reduction in the number of recannulations performed for dislodgement of cannulas.

Verbal consent and explanation of the procedure are a must prior to any intervention as the patient must be included in decision-making. Maintaining hand hygiene is an established way of reducing hospital-acquired infections. It has shown to reduce the transient organisms on the surface of the hand below the level necessary for an infective dose. Hand hygiene can be carried out with conventional washing with soap and water or disinfecting with chlorhexidine rubs. It must be done before and after patient contact. In our initial audit, it was noted that compliance rates were low, and on educating the healthcare professionals, we had a significant improvement in compliance. Gloves are not a substitute for hand hygiene [2, 7].

It is recommended to use powder-free gloves whenever there is a possibility of contact with blood or bodily fluids. They also prevent cross-transmission of microorganisms between the caregiver and the patient. Gloves also protect the caregiver from acquiring an infection during the patient contact. Clean disposable gloves must be used for inserting a peripheral venous cannula or while handling side ports, catheter hubs, etc. Sterile gloves are recommended for the insertion of a central line or parenteral feeding lines and also when handling their dressings.

An aseptic technique is vital when inserting a cannula as it is an invasive procedure and carries with it the chance of catheter-related bloodstream infections [8]. Skin must be disinfected with 2% chlorhexidine with 70% alcohol or povidone-iodine with alcohol solution and must be allowed to dry. They effectively reduce the load of skin flora. The PVC insertion must be carried out using a no-touch technique where we avoid contact with the key parts of the cannula which comes in direct or indirect contact with the bloodstream. The cannula must be secured using a sterile and transparent dressing to monitor the insertion site. The insertion site must be monitored often (8th hourly/pain at the site/signs of inflammation or leakage), and the visual inflammatory phlebitis score (VIP score) must be documented (Table 4) [2, 7].

An appropriate site for the insertion of a peripheral venous cannula is the nondominant upper limb (with preference given to distal veins and then to the proximal veins) avoiding all joints. In particular, the tip of the cannula should not be at a joint line. The vein to be cannulated has to be relatively straight, and if the site of insertion is hairy, then the hair must be clipped and not shaved. In our study, we have not considered the dominance of the person. The appropriate size of the cannula to be used is the smallest gauge which is needed for the recommended therapy. The cannula must be flushed after insertion with either 0.9% normal saline or a heparin solution. The cannula must be changed if there are signs of obstruction (blockage), infiltration (swelling), and phlebitis (VIP score of >2). In the initial audit, the vein was inserted at an appropriate site in only 42% of cases and this was mostly because some part of the cannula was overlying a joint. After educating the healthcare professionals in our reaudit, it was observed that the site was appropriate in 75% of the cases. Appropriate site selection could have led to a statistically significant reduction in the number of recannulation due to either blockage or infiltration.

Documentation plays a vital role in every healthcare professional’s life. It is recommended that all the details pertaining to the procedure of PVC insertions should be mentioned in the patient’s records [9]. It is recommended to document the date and time of insertion, the healthcare professional’s name carrying out the cannulation, site of cannulation, monitoring the condition of the cannula, presence of phlebitis, and information regarding change of cannula or dressing. In our initial audit, it was noted that these data points were not documented in the patient’s record but were documented in a separate phlebotomy register which was available at the nursing station. This was due to a lack of knowledge regarding the need to document this information in the patient’s records as well. The reaudit showed that the documentation of these data points in the patient’s records was seen in 82% of cases which was clinically significant. Accurate documentation encourages research-based standardized practice and should be encouraged.

Education and training of all healthcare professionals involved in the insertion and management of cannula play an important role in the prevention of catheter-related bloodstream infections. PVC insertion is often considered a very simple procedure but if neglected can lead to serious health concerns. In this study, we have taken the RCN guidelines as the standard, and there are other guidelines available which echo the same recommendations [10]. Auditing such routine procedures shows us that even something as simple as PVC can be done incorrectly.

This study highlights the importance of audits in clinical practice. The first audit showed the deficiencies in a routine and simple (but important) procedure like PVC. It has also shown the value of training and reaudits in improving the process and outcome in this procedure. Audits of various processes and their outcome must go through an audit “spiral” in medical institutions.

Limitations of the study include that we have audited only the procedure of insertion and not the care of cannula and handling of the intravenous lines. The initial audit was carried out by a single observer to eliminate bias, and hence, all cannulations that took place in the hospital could not be audited because it was physically impossible for the observer to be there the whole time. The reaudit was carried out by four observers which included the nursing ward incharges. To eliminate bias, we made sure that these observers were competent in the evaluation of the process, and we used the same questionnaire used for the first audit and it had only yes or no as two options to make it as objective as possible.

Conclusions

Peripheral intravenous cannulation although a simple procedure can cause significant morbidity if not performed properly. Auditing such procedures shows deficiencies in performance. Reaudit, after adequate retraining of staff, shows that the performance as well as the outcome of the procedure improves significantly.

References

Barton A, Ventura R, Vavrik B (2017) Peripheral intravenous cannulation: protecting patients and nurses. Br J Nurs 26(8):S28–S33

Denton A, Bodenham A, Conquest A et al (2016) Standards for infusion therapy. Royal College of Nursing. https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-005704. Accessed 9 Jan 2020

Williams DJ, Bayliss R, Hinchliffe R (1997) Surgical technique. Intravenous access: obtaining large-bore access in the shocked patient. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 79(6):466

Mbamalu D, Banerjee A (1999) Methods of obtaining peripheral venous access in difficult situations. Postgrad Med J 75(886):459–462

Social science statistics - Chi Square Calculator. https://www.socscistatistics.com/tests/chisquare/default.aspx. Accessed on 1/9/2020

Social science statistics – Fisher exact test calculator. https://www.socscistatistics.com/tests/fisher/default2.aspx Accessed on 1/9/2020

Loveday HP, Wilson JA, Pratt RJ, Golsorkhi M, Tingle A, Bak A, Browne J, Prieto J, Wilcox M (2014) epic3: national evidence-based guidelines for preventing healthcare-associated infections in NHS hospitals in England. J Hosp Infect 86:S1–S70

Beecham GB, Tackling G (2019) Peripheral line placement. StatPearls

McGuire R, Norman E, Hayden I (2019) Reassessing standards of vascular access device care: a follow-up audit. Br J Nurs 28(8):S4–S12

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE Clinical guideline 139. Prevention and control of healthcare-associated infections in primary and community care

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the staff and administration of Shanthi Hospital and Research Centre for all the help and support towards the conduct of this study in their hospital. The authors would also thank Dr. H. K. Ramakrishna for his valuable inputs for writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lakshmikantha, N., Lakshman, K. The Process and Outcomes of Peripheral Venous Cannulation in a Tertiary Care Center: a Prospective Completed Audit Loop Study. Indian J Surg 84, 35–39 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-021-02782-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12262-021-02782-6