Summary

Background

Brain metastases (BM) still present a clinical challenge in oncology. Treatment of BM was mainly based on local approaches including neurosurgery and radiation. However, the fraction of patients with asymptomatic BM has risen over the last decade. Recent clinical trials on immune- and targeted therapies showed promising intracranial responses—especially in neurological asymptomatic status. Therefore, systemic treatment presents an emerging therapy approach specifically in patients with asymptomatic BM.

Methods

The present review highlights the recent advances in systemic therapeutic and preventive approaches in BM focusing on the main BM causing tumors: non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), melanoma and breast cancer.

Results

Remarkable intracranial efficacies were presented for several next-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and immune checkpoint inhibitors, especially in asymptomatic BM patients. In NSCLC, osimertinib and afatinib presented intracranial response rates over 80%. Osimertinib showed even a potential for primary BM prevention. Considerable intracranial response rates were observed for the combination of dabrafenib and trametinib in BRAF mutated melanoma BM. Combined ipilimumab and nivolumab treatment in asymptomatic melanoma BM even presented with similar intra- and extracranial response rates. In breast cancer, HER2-targeted TKIs like lapatinib in combination with chemotherapy, or trastuzumab deruxtecan monotherapy presented also notable intracranial response rates.

Conclusion

New developments in targeted and immune-modulating therapies have postulated high intracranial efficacies in patients with BM from different solid tumors. However, more BM-specific studies and BM-specific endpoints in registration trials are warranted to underscore the role of systemic treatment in patients with BM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Brain metastases (BM) are associated with a severe impact on quality of life and survival prognosis. Beside the common primary tumors causing BM including lung cancer, breast cancer and melanoma, the incidence of BM due to colon cancer, renal cell carcinoma and rare tumor types were reported to be rising resulting in BM being the most common tumor of the central nervous system [1]. However, the clinical presentation and the clinical course of BM have changed over the last decades, leading to a new field of therapeutic and preventive approaches and an improvement of prognosis in brain metastatic patients.

Neurological symptom burden in BM: inclusion in treatment decisions?

Due to wider application and availability of BM screening, the clinical presentation of BM has changed during the last decades. Analyses from a large real-life cohort uncovered a rising incidence of BM diagnosed during screening and staging procedures in absence of neurological symptoms over the last decades [1, 2]. While in the 1990s, the incidence of asymptomatic patients at BM diagnosis was 15.3%, in the period from 2000–2009 the incidence had already doubled to 31.4%. Furthermore, this subgroup of BM patients was associated with a significantly longer survival prognosis (11 vs. 7 months) and presented more frequently an extracranial progression (35.7% vs. 50.3%) as major cause of death, compared to symptomatic patients. Therefore, combined intra- and extracranial disease control as well as prevention of long-term neurocognitive toxicity has to be considered in treatment planning of asymptomatic BM patients.

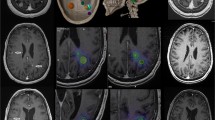

Thus, the current European Association of Neuro-oncology (EANO) guidelines for BM treatment recommends the more invasive therapeutic approaches like neurosurgical resections, stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) and whole-brain radiotherapy (WBRT) in patients with high intracranial symptom burden in need for immediate symptom relief, while initial systemic treatment should be evaluated in patients with asymptomatic BM—if intracranially active systemic treatment is available. In the event of low performance status and/or progressive systemic disease with limited survival prognosis, the use of WBRT or best supportive care should be evaluated (Fig. 1; [3, 4]). Importantly, best supportive care as the primary treatment approach should not be underrated in patients with limited survival prognosis as the QUARTZ (Quality of Life after Radiotherapy for Brain Metastases) trial—a randomized phase III trial comparing BSC with WBRT versus BSC alone for patients with BM from NSCLC—showed no significant differences in overall survival or quality of life between the groups [5].

Treatment strategies in patients with BM (based on and adapted from Steindl and Berghoff [4])

New era of BM treatment: systemic therapies as initial treatment approach

Indeed, a major step of systemic treatment in advanced cancer was the successful introduction of immune-related therapy as well as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI) in several BM-causing tumor entities during the last decades. BM-specific endpoints as well as inclusion of brain metastatic patients have been implemented in several modern trials on targeted and immune-modulating therapies, resulting in various studies presenting remarkable intracranial efficacies—especially, in patients with neurological asymptomatic disease ([4]; Table 1). In line with this, several studies also revealed an intracranial expression of predictive biomarkers—even though with heterogeneity between the sites—further supporting the evaluation of these emerging treatment approaches in metastatic brain cancer [6].

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors in BM treatment

Third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) TKIs like osimertinib presented remarkable intracranial response rates over 80% in patients with EGFR-mutated metastatic lung cancer and asymptomatic BM [7,8,9]. In contrast to first- and second-generation EGFR TKIs, osimertinib is even active in the presence of an EGFR T790 mutation—a point mutation of the EGFR, which is responsible for more than 50% of treatment resistances to first- and second-generation EGFR TKIs. Furthermore, also in ALK- and ROS1 rearranged NSCLC, only the third generation ALK inhibitors alectinib, lorlatinib and brigatinib were associated with meaningful intracranial response rates over 65% [10,11,12,13,14]. In the registration trials of alectinib and lorlatinib even small subgroups of pretreated and symptomatic BM patients were included; however, compared to asymptomatic patients, reduced intracranial efficacies were observed [10, 12].

Similar high intracranial response rates (78.9%) were observed for combined BRAF-inhibitor dabrafenib and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) inhibitor trametinib in BRAF V600E-mutated and asymptomatic melanoma BM [15]. However, in case of symptomatic BM with or without previous treatment, the intracranial response rates of combined treatment approaches were reduced (59%) [15].

The HER2 subtype in breast cancer presents the most favorable prognosis after diagnosis of BM as survival prognosis of up to 24 months and longer can be observed [1]. While in luminal and triple negative breast cancer only limited to no proven targeted therapy approaches with favorable intracranial efficacies are available, HER2-directed treatment has shown successful intracranial responses in HER2 overexpressed breast cancer BM. On the one hand, combination treatment approaches as HER2-targeted TKI like lapatinib, neratinib or tucatinib in combination with chemotherapy, and HER2-targeted antibodies like trastuzumab and pertuzumab in combination with chemotherapy have shown intracranial efficacies (intracranial response rates: 31–57%) [16,17,18,19]. On the other hand, HER2-targeted antibody–drug conjugate monotherapy with the more potent trastuzumab deruxtecan, an antibody–drug conjugate composed of an anti-HER2 antibody and a cytotoxic topoisomerase I inhibitor, presented with almost identical extracranial (58%) and intracranial (62%) response rates in heavily pretreated HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients [20].

Immune checkpoint inhibitors in BM treatment

The PD‑1 directed immune checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab as monotherapy in melanoma BM presented an intracranial response rate of 22%—only about half of that seen in extracranial disease (40%) [21]. In contrast, the combined therapy of the PD‑1 inhibitor nivolumab with the CTLA‑4 inhibitor ipilimumab in asymptomatic melanoma BM showed similar intra- and extracranial response rates up to 47–55% [22]. This study also allowed the inclusion of a subgroup of symptomatic melanoma BM, which showed lower intracranial efficacy in symptomatic (clinical benefit rate: 22.2%) compared to asymptomatic (clinical benefit rate of 58.4%) BM patients [23]. However, 87% of the asymptomatic BM patients still had an ongoing response at the time of data cutoff, underscoring the more durable responses of immune directed therapy compared to BRAF/MEK inhibitor treatment in melanoma BM.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, either as monotherapy or in combination with chemotherapy, targeting the PD‑1 (nivolumab/pembrolizumab) or the PD-L1 (atezolizumab) axis are well-established treatment approaches in metastatic NSCLC. In a phase II study of pembrolizumab in NSCLC an intracranial response rate of 33% and an extracranial response rate of 50% could be observed [21]. Furthermore, the intracranial efficacy of nivolumab was postulated as not inferior compared to the extracranial efficacy (intracranial: 9% vs. extracranial: 11%) in NSCLC with locally pretreated, active BM [24]. In addition, atezolizumab was even associated with a secondary BM preventive potential in patients with treated BM [25]. In a post hoc analysis of the OAK trial comparing the PD-L1 inhibitor atezolizumab to docetaxel as a second-line treatment in NSCLC, the median time to new BM lesions was lower with atezolizumab than with docetaxel (not reached vs. 9.5 months; HR = 0.42; 95% CI: 0.15–0.18) [25].

In breast cancer, up to now, only the IMpassion130 has presented an overall survival benefit for an immune checkpoint inhibitor-based therapy in patients with newly diagnosed, triple-negative locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer [26]. Even though brain metastatic patients have been excluded from this registration trial, a BM-specific prospective trial is currently investigating the intracranial efficacy of atezolizumab-based treatment combined with (nab‑) paclitaxel in triple-negative breast cancer patients irrespective of PD-L1 expression (NCT03483012).

Prevention of brain metastasis: the new landmark of systemic treatment?

For a long time, prophylactic cranial irradiation (PCI) presented the only possible approach to prevent BM. However, due to the unfavorable neurological side effects and the limited impact on prognosis, the use of PCI is restricted to specific indications [3]. As the treatment of symptomatic BM is challenging and the overall survival prognosis still poor, secondary and primary prevention of BM by systemic treatment came into the focus in recent years (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Primary BM prevention in selected NSCLC studies (adapted from Steindl and Berghoff [4])

In the FLAURA trial, comparing osimertinib with standard EGFR-TKI, 3% of patients without BM at baseline developed BM during the follow-up in the osimertinib group compared to 7% in the standard EGFR-TKI group. Furthermore, 19% of patients with BM at baseline developed new or progressive BM in the osimertinib group compared to 43% in the standard EGFR-TKI group [27].

Primary BM prevention of third generation ALK inhibitor alectinib compared to crizotinib was investigated in the ALEXA trial. In the crizotinib arm, 31.5% of the patients without BM at study entry developed BM during further course of the study, compared to only 4.6% of the patients in the alectinib group [10].

Furthermore, the addition of durvalumab to radiochemotherapy in stage III NSCLC was associated with an improved primary BM prevention as 5.5% of patients in the durvalumab arm developed BM compared to 11.0% in the control arm [28].

Conclusion

Remarkable intracranial efficacies were observed for several next-generation TKIs and immune checkpoint inhibitors—especially in patients with asymptomatic BM. Therefore, in case of available systemic treatment option with proven high intracranial efficacy, upfront systemic treatment can be evaluated in BM patients with asymptomatic disease.

Furthermore, based on the promising primary and secondary BM preventions in some new therapeutic agents, effective prevention of BM also needs to be addressed in future trials.

Take home messages

-

Targeted and immune directed therapy presented notable intracranial response rates especially in asymptomatic brain metastases.

-

Some immunotherapy and targeted therapy agents have shown primary and secondary BM prevention in clinical trials.

Change history

17 August 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12254-022-00827-4

References

Steindl A, Kreminger J, Moor E, et al. Clinical characterization of a real-life cohort of 6001 patients with brain metastases from solid cancers treated between 1986–2020. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:S397.

Steindl A, Yadavalli S, Gruber KA, et al. Neurological symptom burden impacts survival prognosis in patients with newly diagnosed non-small cell lung cancer brain metastases. Cancer. 2020; https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33085.

Soffietti R, Abacioglu U, Baumert B, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of brain metastases from solid tumors: Guidelines from the European Association of neuro-oncology (EANO). Neuro Oncol. 2017;19:162–74.

Steindl A, Berghoff AS. Brain metastases in metastatic cancer: a review of recent advances in systemic therapies. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2020; https://doi.org/10.1080/14737140.2021.1851200.

Langley RE, Stephens RJ, Nankivell M, et al. Interim data from the medical research council QUARTZ trial: does whole brain radiotherapy affect the survival and quality of life of patients with brain metastases from non-small cell lung cancer? Clin Oncol. 2013; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clon.2012.11.002.

Lah TT, Novak M, Breznik B. Brain malignancies: glioblastoma and brain metastases. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.10.010.

Reungwetwattana T, Nakagawa K, Cho BC, et al. CNS response to osimertinib versus standard epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with untreated EGFR-mutated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:3290–7.

Schuler M, Wu Y‑L, Hirsh V, et al. First-line Afatinib versus chemotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and common epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations and brain metastases. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:380–90.

Wei YF, Lim CK, Tsai MS, et al. Intracranial responses to Afatinib at different doses in patients with EGFR-mutated non-small-cell lung carcinoma and brain metastases. Clin Lung Cancer. 2019; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cllc.2019.02.009.

Gadgeel S, Peters S, Mok T, et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in treatment-naive anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive (ALKþ) non-small-cell lung cancer: CNS efficacy results from the ALEX study. Ann Oncol. 2018; https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy405.

Novello S, Mazières J, Oh IJ, et al. Alectinib versus chemotherapy in crizotinibpretreated anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: results from the phase III ALUR study. Ann Oncol. 2018; https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy121.

Solomon BJ, Besse B, Bauer TM, et al (2018) Lorlatinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a global phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 19(12):1654–67

Bauer TM, Shaw AT, Johnson ML, et al. Brain penetration of Lorlatinib: cumulative Incidences of CNS and non-CNS progression with Lorlatinib in patients with previously treated ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. Target Oncol. 2020; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-020-00702-4.

Camidge DR, Kim HR, Ahn MJ, et al. Brigatinib versus crizotinib in ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018; https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1810171.

Davies MA, Saiag P, Robert C, et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with BRAFV600-mutant melanoma brain metastases (COMBI-MB): a multicentre, multicohort, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30429-1.

Swain SM, Baselga J, Miles D, et al. Incidence of central nervous system metastases in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer treated with pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel: results from the randomized phase III study CLEOPATRA. Ann Oncol. 2014; https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu133.

Bachelot T, Romieu G, Campone M, et al. Lapatinib plus capecitabine in patients with previously untreated brain metastases from HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (LANDSCAPE): a single-group phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2013; https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70432-1.

Freedman RA, Gelman RS, Anders CK, et al. TBCRC 022: A phase II trial of neratinib and capecitabine for patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2‑positive breast cancer and brain metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2019; https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.01511.

Murthy RK, Loi S, Okines A, et al. Tucatinib, trastuzumab, and capecitabine for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020; https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1914609.

Modi S, Saura C, Yamashita T, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020; https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1914510.

Goldberg SB, Gettinger SN, Mahajan A, et al. Pembrolizumab for patients with melanoma or non-small-cell lung cancer and untreated brain metastases: early analysis of a non-randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016; https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30053-5.

Long G, Atkinson V, Menzies AM, et al. A randomized phase II study of nivolumab or nivolumab combined with ipilimumab in patients (pts) with melanoma brain metastases (mets): the Anti-PD1 Brain Collaboration (ABC). J Clin Oncol. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.9508.

Tawbi HA, Forsyth PA, Algazi A, et al. Combined nivolumab and Ipilimumab in melanoma metastatic to the brain. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:722–30.

Gauvain C, Vauléon E, Chouaid C, et al. Intracerebral efficacy and tolerance of nivolumab in non-small-cell lung cancer patients with brain metastases. Cancer Treat Res. 2018; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.12.008.

Gadgeel SM, Lukas RV, Goldschmidt J, et al. Atezolizumab in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer and history of asymptomatic, treated brain metastases: exploratory analyses of the phase III OAK study. Cancer Treat Res. 2019; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.12.017.

Schmid P, Adams S, Rugo HS, et al. Atezolizumab and nab-paclitaxel in advanced triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018; https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1809615.

Ramalingam SS, Gray JE, Ohe Y, et al. Osimertinib vs comparator EGFR-TKI as first-line treatment for EGFRm advanced NSCLC (FLAURA): final overall survival analysis. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(suppl):v851–934.

Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, et al. Durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017; https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1709937.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

A.S. Berghoff has research support from Daiichi Sankyo (≤ 10,000 €), Roche (> 10,000 €) and honoraria for lectures, consultation or advisory board participation from Roche Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Merck, Daiichi Sankyo (all < 5000 €) as well as travel support from Roche, Amgen and AbbVie. A. Steindl declares that she has no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: The licence information was missing from this article and should have been “Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/”.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Steindl, A., Berghoff, A.S. Brain metastases: new systemic treatment approaches. memo 14, 198–203 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12254-021-00709-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12254-021-00709-1