Abstract

Wild edible plants are important for the livelihoods of both rural and urban people in West Africa, but little is known about their trade networks. This study identifies, quantifies, and characterizes the local trade of wild edible plants in northern Guinea-Bissau to better understand the linkages between wild edible plants, local markets, and livelihoods, and to evaluate the sector’s ecological and economic sustainability. Interviews with 331 market vendors in the capital Bissau and in five sub-regional urban markets revealed that 19 products from 12 species were traded, with an estimated annual retail value of at least 707,000 USD for a volume of 354 metric tons (tonnes). These products are mainly harvested from the country’s woodlands by female vendors in sub-regional markets and are primarily traded to Bissau or neighboring countries. However, increasing demand and persisting deforestation for cashew plantations coupled with a lack of management strategies raise concerns about the long-term availability of certain wild edible plants. The study’s findings are also discussed in terms of their implications on local livelihoods, particularly for rural women who rely on the trade of wild products for income and as a social safety net. We highlight the need to secure women’s roles and enhance their collective power in added value chains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Non-timber forest products (NTFPs) refer to biological products other than timber harvested from wild species at various landscapes or ecosystems for human use (De Beer and McDermott 1989; Shackleton et al. 2011). In the West African drylands, rural and urban dwellers have a longstanding reliance on a wide array of NTFPs for household sustenance and income generation (Heubach et al. 2011; Leßmeister 2017). Given widespread food insecurity and malnutrition in the region (FAO et al. 2023), wild edible plants are often ranked by local communities as the most important subsistence NTFP harvested both from woodland and non-woodland environments (Assogbadjo et al. 2012; Djagoun et al. 2022; Nabaloum et al. 2022; Segnon and Achigan-Dako 2014). Edible products from wild plants are also extensively traded in the informal local markets within the region and can contribute to as much as 20% of the overall household income (e.g., Heubach et al. 2011).

The economic benefits of NTFPs to rural livelihoods in West Africa have been recognized for decades in the scholarly literature (e.g., Chambers and Leach 1987). While due to inefficient commercial production and trade networks, NTFPs alone are unlikely to be a means of escaping poverty (Angelsen et al. 2014; Belcher et al. 2005; Wunder et al. 2014), they serve as a crucial monetary base for both rural and urban populations, including collectors, processors, and traders (Shackleton et al. 2007). Furthermore, in certain political and social contexts, market integration and commercialization for high-income export markets can provide additional income options for the actors in the NTFP value chains. However, the risks associated with overexploitation of the wild resources, elite capture of the economic benefits, further marginalization of vulnerable groups such as women, and poor communities or replacement of common property regimes are considerable (Wynberg et al. 2015). For instance, the increased international market demand for Shea nuts (Vitellaria paradoxa C.F. Gaertn) harvested from the wild for the chocolate and cosmetic industries has resulted in resource pressure, tenure privatization, and competition between men and women in Burkina Faso (Gausset et al. 2005), while in Mali, middlemen undercut economic benefits of women collectors (Naughton et al. 2017). Indeed, producers often try to bypass middlemen, but given the poor infrastructure in many remote areas and the financial constraints of many rural households, middlemen play a major role in NTFPs’ value chains (Rousseau et al. 2015).

Despite some international trade, local markets in the West African drylands continue to serve people’s needs as they have fewer regulations and are more accessible to small collectors and producers (Shackleton et al. 2007). This is particularly relevant for rural women who often lack formal education and access to credit (Pérez et al. 2002). Indeed, in the rural African context, it is thought that men primarily deal with cash crops and women focus on food production and collection of NTFPs for both domestic use and sale in the local markets (Sunderland et al. 2014). However, the social and economic dynamics of NTFPs’ local markets in the region, and local wild food markets in particular, remain understudied. This oversight is especially remarkable given that global production networks of high-priced products such as Shea butter or baobab (Adansonia digitata L.) powder are often intertwined with and dependent on these local markets (Meinhold and Darr 2022; Wardell et al. 2021). At the same time, regions or countries excluded or poorly integrated into formal markets and value chains often absorb the social and environmental impacts embodied in the production and exports of wild species commodities through displacement of demand elsewhere with little or no value retained locally (Meyfroidt et al. 2013). Moreover, locally important species traded within domestic markets are commonly disregarded by international researchers and development agencies as low-value products and are not subject to much economic analysis (Shackleton and de Vos 2022). Understanding these links is key to designing sustainable resource management for both the species traded and the actors involved in their value chains (de Mello et al. 2020).

This article aims to contribute to a better understanding of the linkages between wild edible plants, local markets, and livelihoods in the dry landscape of northern Guinea-Bissau to evaluate the sector’s ecological and economic sustainability. To our knowledge, and apart from the study by Catarino et al. (2019) which focused on the nutritional proprieties of the wild edible leafy vegetables sold in Bissau, the capital city, no previous research has been published on NTFPs in Guinea-Bissau. Our main objectives were to: (1) describe which wild edible plants are traded in the capital and the local markets of northern Guinea-Bissau; (2) quantify the prices and minimum volumes marketed; (3) unveil where the plant products are collected and who the actors involved in their trade are, and; (4) evaluate recent trends on the demand and availability of marketed products, as perceived by the vendors involved. We also discuss the implications of our findings to unlock the potential of wild edible plants trade towards more sustainable and inclusive regional development.

In Guinea-Bissau, like many other West African countries, the consumption of wild plants for food purposes plays a pivotal role in local livelihood strategies. Guinean peoples have been involved in regional trade circuits for centuries (van der Ploeg 1990) and observations of NTFP barter and trade are as early as the first written records of the area by the Europeans (Coelho 1953; d’Almada 1594; Donelha and Hair 1977). However, during Portuguese colonial rule, there was a shift towards specialization in a few crops or products for export-oriented markets (Temudo and Abrantes 2013). Groundnuts (Arachis hypogaea L.) were the main crop exported until independence, and by 1970, cashew nut (Anacardium occidentale L.) exports ranked third, behind palm oil (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) kernels (mainly collected from wild palms) (Spínola 1972). In the years following independence in 1974, amid political instability, Guinea-Bissau adopted a series of neoliberal policies which had significant implications for the food sector (Lourenço-Lindell 1995). Agricultural growth was mainly observed in the cashew nut production, bartered for imported cheap rice (the country’s staple food), eroding local rice production (Temudo and Abrantes 2013). The economy was largely informal, leading to the growth of spontaneous food markets fueled by small-scale traders in the outskirts of urban areas (Lourenço-Lindell 1995). With the advent of economic liberalization in the late 1980s, Guinea-Bissau joined the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU), which led to the resurgence of transboundary commerce. In this economic context, the country established itself as one the world’s largest producers of cashew nuts, a position it has maintained until today (FAO 2023) at the expense of its natural woodlands. While there are no official statistics regarding the state of natural resources, the population of Guinea-Bissau has been heavily reliant on its extraction. Sectors such as agriculture, fisheries, and forestry jointly accounted for 44% of the GDP between 2001 and 2017 and employed more than 80% of the working population (GoGB 2021). Woodland clearance to create space for cashew plantations is commonly identified as the main driver of deforestation in the country (Temudo et al. 2015). Exports of raw shelled cashew nuts account for 89 to 96% of the country’s total export earnings (estimates from 2019 to 2022) (IMF 2022, 2023). This heavy dependence on a single commodity has led to the least diversified export base within the ECOWAS (IMF 2015), exposing Guinea-Bissau to increased vulnerability when it comes to production and market fluctuations (Catarino et al. 2015).

Methods

Study Area

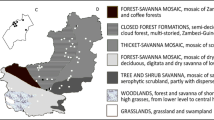

This study is focused on northern Guinea-Bissau, which encompasses the most densely populated regions of the country (> 30 inhabitants /km2) (Temudo et al. 2020). The main ethnic groups in the north are also the most dominant in the country and include Manjack, Balanta, Mandinka, and Fulani. While the Fulani traditionally rely on pastoralism, in the past decades, they have also adopted farming as a significant means of livelihood (Moritz et al. 2009). On the other hand, the other ethnic groups are subsistence farmers whose main crops include rice, groundnuts, sorghum, millet, maize, and sweet potato. The rural landscape in northern Guinea-Bissau is characterized by a mosaic of cashew plantations, fallows, upland and lowland rice fields (mpampam and bolanhas), and patches of semi-natural woodland. The woodland vegetation predominantly denotes the Sudano-Guinean transition zone type and includes tree species such as Albizia zygia (DC.) J.F.Macbr., Daniellia oliveri (Rolfe) Hutch. & Dalziel, Hexalobus monopetalus (A.Rich.) Engl. & Diels, Lophira lanceolata Tiegh. ex Keay, Parkia biglobosa (Jacq.) R.Br. ex G.Don, Piliostigma thonningii (Schumach.) Milne-Redh., Prosopis africana (Guill. & Perr.) Taub., Pterocarpus erinaceus Poir., and Terminalia macroptera Guill. & Perr. The shrub and climber layers include Annona senegalensis Pers., Combretum micranthum G. Don, Guiera senegalensis J.F.Gmel., Icacina oliviformis (Poir.) J.Raynal, Landolphia heudelotii A.DC., Saba senegalensis (A.DC.) Pichon, and Uvaria chamae P.Beauv. (Catarino et al. 2008).

Interviews and Data Analysis

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with market vendors selling wild edible plant products in Bissau, the capital of Guinea-Bissau, as well as in five weekly sub-regional urban markets called lumos. The lumos visited are located in the administrative regions of Cacheu, Oio, and Bafatá (Fig. 1). Over 50 lumos are held in Guinea-Bissau, but we focused on these five because preliminary work indicated they were the primary suppliers of wild edible plant products to the capital markets, and we were also interested in investigating the price differences between the capital markets and the lumos. Additionally, our sample aimed to capture the various roles played by different lumos in the informal movement of goods within the country. Some lumos primarily serve local consumers (the case of Canchungo, Mansabá and Bambadinca), others supply other lumos and Bissau markets (case of Bula and Mansôa), and there are also “transition” lumos that facilitate cross-border exchange (not included in our sample, although this dynamic was also observed in the lumos visited and further documented). Rural villagers surrounding the lumos visited belong to the Manjack in Canchungo, the Balanta in Bula and Mansôa, the Mandinka in Mansabá, and the Fulani in Bambadinca.

Location of all lumos in Guinea-Bissau (woodland cover mapped according to the FAO definition of forest (2018): patches more than 0.5 ha and more than 10% crown cover. Provided by RSeT NGO). Data on lumos was sourced from the National Research Institute (note that there could be smaller lumos that are not shown in the figure)

To ensure a representative sample of wild edible plant products sold in the markets, we conducted interviews before (March–June 2022) and after (November–December 2022) the rainy season which lasts between July and October. Vendors were selected on a voluntary basis after explaining the research project’s objectives, the implications of their participation, and how their responses will be used. Given time constraints during fieldwork, we tried to interview 60 vendors in each season in the capital and 20 vendors in each season in each lumo. This target was achieved in all markets, except in 4 out of 5 lumos after the rainy season when these products are less available and there are fewer vendors. These numbers represent about 50 to 70% of the vendors selling wild edible plant products available at these locations during these periods. Vendors were randomly selected across the stalls available on that given market and period. About 10% of the vendors approached by the authors in a given market refused to be interviewed, expressing concerns about the “bad luck” that the product weighing activities (see below) could have on the possibility of selling them, or the misconception that the researcher was associated with a tax authority. Vendors were randomly selected across the stalls available on that given market and period. In total, 331 vendors who sold wild edible plants agreed to participate in the study (Table 1). The iNext package was used in R 4.3.2 to compute product and species diversity estimates (number and relative abundance) for rarefied and extrapolated (R/E) samples in each location. Figure 1 in Electronic Supplemental Material (ESM) shows an R/E sampling curve that indicates our survey covered a large portion of the total product and species diversity. However, it also suggests that, ideally, we should have had a larger sample from the Bambadinca, Bula, and Mansabá lumos to capture the diversity.

In each vendor stall, we recorded all wild edible plant products offered for sale, whether the products were sold in dried or fresh condition, how these products were processed to be consumed, their seasonal availability, their habitat of origin, geographic origin, and how they were obtained. No voucher specimens were collected because the authors are well-versed in Guinea-Bissau’s flora and the recorded plant products are widely traded and commonly consumed by the Bissau-Guinean population. For the plant products sold by more than 10% of vendors (see Table 1 in ESM), we documented the prices of sale units (e.g., cup, bundle, bottle, bucket) and asked vendors to estimate their daily/weekly/monthly sales. Each of these units was weighted with a digital scale for later conversion to price/kilogram. We show the prices separately because there was a clear price variation between vendors who collected the products themselves (collectors) and those who were only retailers. From this data, and considering product seasonality, we calculated the minimum annual volumes offered for sale per market stall (because the production of Saba senegalensis fruits varies throughout the year, we have opted to account for only a 6-month availability period). To estimate the total product volume, we multiplied the average volume per market stall by the number of vendors selling the product. The total retail value was determined by multiplying the average annual volume by the lowest season price (either before or after the rainy season). Additionally, we inquired whether vendors had noticed any changes in the availability or price of these products in the last decade, if other products sold were more economically significant than wild edible plants, and the type of trading challenges they faced. The ethnicity, gender, and age of the vendors were also recorded.

Based on the data collected, we considered that the trade of a species’ product can be: (1) ecologically sustainable if, (a) the species is not listed as endangered on the IUCN Red List; (b) harvested parts can be sustainably sourced (e.g., no roots or uprooting); (c) vendors report no declines in abundance or significant price increases in the last decade; (d) effective management, monitoring, and traceability systems are in place; and, (2) economically sustainable if, (e) the trade generates substantial annual retail values; (f) price fluctuations are minimal; (g) value addition activities are implemented throughout the supply chain; and (h) there are no significant trade barriers, especially for the upstream actors in the value chain, although one recognizes that both ecological and economic factors are interconnected and can influence each other.

The study was carried out according to the research ethics guidelines of the Norwegian National Committee for Research Ethics in the Social Sciences and the Humanities and the Code of Ethics of the International Society of Ethnobiology (2006). A notification form was submitted to the Norwegian Centre for Research Data based on these guidelines and approved prior data collection.

Results

Products Traded, Volumes, and Prices

In Bissau city, a total of 14 products from seven different species of wild edible plants were traded for food purposes. On the other hand, in the lumos, a total of 18 products from 12 different species were traded for food purposes (see Table 1 in ESM). The total number of species found included six trees, three woody climbers, two palms, and one herbaceous climber. Eight products were traded in Bissau by more than 10% of the vendors, while in the lumos, six products were traded by more than 10% of the vendors, including baobab fruit, fruit powder and leaf powder, velvet tamarind (Dialium guineense Willd.) fruit, palm oil and fruit, African locust bean (Parkia biglobosa) fruit and netetu (its fermented seeds), Saba senegalensis fruit, and tamarind (Tamarindus indica L.) fruit. Most fruits are mainly consumed as juice after being blended with water and sugar but can also be eaten raw or as an ingredient in various traditional dishes. Palm fruit and oil (extracted from previously sun-dried and boiled fruits) are essential ingredients in traditional Bissau-Guinean cuisine, cooked with rice, fish, meat, or vegetables. Despite having a peak-production season, most of the products sold by more than 10% of the vendors are available year-round, typically with low conservation needs as they are mostly sold dry. Apart from netetu and netetu powder, baobab leaf powder, and palm oil, the products are sold very little processed (e.g., cleaning of fiber residues, husking).

In Bissau city, the eight most frequently traded products accounted for a total annual volume of 162,000 kg (plus 24,000 L of palm oil), ranging from 1,300 kg for baobab leaf powder to 71,000 kg for its fruit. In the lumos, the six most frequently traded products accounted for a total annual volume of 192,000 kg (plus 47,000 L of palm oil), ranging from 11,000 kg for Saba senegalensis fruit to 120,000 kg for baobab fruits (Fig. 2). All vendors in Bissau city were retailers, which sold their products for an average price ranging from 981 FCFA/kg (1.66 USD) for baobab fruit to 3,643 FCFA/kg (6.16 USD) for netetu. Apart from palm oil, where there is a decrease between collectors’ prices and retailers’ prices (possibly connected with the imports of industrially produced palm oil from the neighboring countries), price differences between collectors and retailers in the lumos represent an average percent increase of 75%. Average prices range from 227 FCFA/kg (0.38 USD) for the fruit of Saba senegalensis to 1,874 FCFA/kg (3.17 USD) for velvet tamarind fruit (see Table 2 in ESM). All prices increased after the rainy season. In our sample, for the most frequently traded products, we estimate an annual retail value of 251 million FCFA (424,000 USD) in Bissau and 167 million FCFA (282,000 USD) in the lumos.

Market Structure and Dynamics

Women’s Participation and Role

Most vendors interviewed were females (94%) and from the Balanta ethnic group (46%), which sold only wild edible plants (in the lumos) or in combination with cultivated plants like millets, fonio, rice, groundnuts, cassava, and bissap (flowers from Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) (in Bissau markets). In the case of selling cultivated products, vendors mentioned that these were either equally or more economically significant than the sale of wild edible plants. In the lumos, vendors highlighted the safety net role that wild products play for the households both as an income source and direct consumption, with comments such as “I only sell the product [African locust bean fruit] if I need the money, usually I collect and save it at home because during the rainy season it feeds the children and helps prevent malaria.” (female vendor in Mansabá).

Women vendors played a crucial role in the distribution of the products across locations. They directly acquired large quantities from the lumos to sell them in Bissau city, while those vendors in the lumos usually gathered and processed the products themselves, typically selling just one or two products. However, the collection process could involve more actors depending on the type of product, as some can be challenging to harvest and time-consuming. For instance, it is common to involve other family members or pay young males to collect baobab fruits and African locust bean pods, as these trees are tall and require climbing. When it comes to oil palm, women typically pay experienced harvesters between 100 and 150 FCFA (0.17–0.25 USD) for each fruit bundle. Young men primarily conduct this work; however, female vendors have noted the current scarcity of labor available for such activity. The extraction of oil is always carried out by women in rural households.

Some women established networks and collaborations with fellow vendors to trade these products, but they encountered significant barriers mentioned in the interviews. Limited education levels diminished their ability to bargain about prices. Many vendors from the villages surrounding the lumos, who only speak their ethnic language, struggled to negotiate in Creole (the main language spoken in the capital) or give correct money change to buyers. This led to unfair pricing and vendors often being harassed to reduce prices.

Product Origin and Distribution

Both Bissau city and lumos vendors identified the woodlands as the main source habitat for their products. However, it should be noted that the general Creole term “mato” (here translated to woodland) might also encompass fallows (abandoned farmland rather than natural woodland) (Frazão-Moreira 2009). In Bissau city, vendors had limited knowledge about the geographic origins of the wild edible plants they sold. This was different from vendors in the lumos, although some refused to share information on the geographical source of their products.

Bissau city vendors had two main channels for obtaining these NTFPs products: (1) they either traveled to the largest lumos like Bula, Bissorã, Mansôa, Tchalana, and Nhacra; or, (2) purchased from urban wholesalers in Bissau city itself. When purchasing from the latter, the products were typically imported from Guinea-Conakry, Senegal, Mali, and Sierra Leone (one can highlight tamarind and velvet tamarind fruits which were less available in the lumos). For palm oil and fruit, the involvement of intermediaries from neighboring countries has been common, as vendors highlighted. However, imported oil has a negative reputation due to the use of processing mills, resulting in flavorless and malodorous oil according to a vendor’s comment. As a result, most of the available volume in the markets was extracted in the south or Cacheu region and was comparatively highly priced.

Bula and Mansôa capture the most volumes, with a significant portion of the wild edible plant products for sale being the vendors’ harvest (73% and 85% respectively). In the Canchungo and Bambadinca lumos, these products were less common and characterized by low trading volumes, being primarily sourced in other lumos as they typically happen on different weekdays. However, palm oil and fruit and Saba senegalensis fruit were always obtained from the vendors’ harvest. In Mansabá lumo, the smallest and most remote lumo sampled, 70% of the products were vendors’ harvest.

Species Availability and Product Demand

Vendors noted a substantial fluctuation in the supply and demand for these products throughout the year, leading to varying prices. These variations were mainly attributed to factors such as product seasonality, cashew harvesting season, certain festivities, lack of transportation and storage facilities, availability of substitutes, and collection of taxes by the agents of the General Directorate for Forests and Fauna (DGFF). Some examples of these interconnected relations were the unstable electricity that hinders the processing into ice lollies (a popular form of consumption of many juices from these products) or the fact that in some traditional dishes within specific ethnic groups, the use of okra leaves (Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) Moench.) is preferable to baobab leaf powder; thus, the demand for baobab leaf powder declines when okra is in season. However, many vendors commented on the reduced availability in the last decade for some of the most traded species (African locust bean, baobab, and velvet tamarind) in the woodlands with comments such as “nowadays these products are harder to get than before” (female vendor in Bambadinca) or “the price has been increasing because the product is difficult to findin the wild” (female vendor in Bula) (Table 2).

The interviews conducted after the rainy season revealed that low demand in this period prompted many vendors in Bissau to halt the sale of these wild plant products, which they connected with the inflation of food prices in the capital caused by the COVID-19 outbreak and the Russo-Ukrainian war. Prior to the rainy season, vendors generally reported a growing demand, which, according to them, was believed to be linked to the development of export markets, a new set of customers because of increased urbanization (e.g., hotels, restaurants, and other touristic facilities looking for traditional products), and a reduction in cashew exports in recent years.

Cross-border Trade

Vendors mentioned that competition for the most frequently traded wild edible plants has increased in recent years, partly due to the involvement of international actors from neighboring countries in the value chain, which otherwise, apart from oil palm products, used to be very short. According to vendors’ comments, foreigners were wholesale buyers during the peak season, either exporting the products or reselling them in Bissau during the lean season at significantly higher prices. When acquiring the products in the lumos, vendors in Bissau often faced challenges of limited surplus or lack of purchasing power. Encounters with international buyers were not only common in the lumos but also in the villages. Senegalese buyers, for example, reported the lack of baobab fruit in Senegal and the preference towards the one growing in Guinea-Bissau. Some vendors noted that “Senagalese fill whole trucks” (female vendor in Bissau) with Saba senegalensis fruit. Some vendors also reported that foreigners can harvest the products themselves without asking permission or disregarding traditional rules such as mangiduras—an oscillating common property regime, often observed among the Mande peoples, which defines rules that seasonally regulate access to vegetation and wildlife (Freudenberger et al. 1997). Since wholesale is deemed preferable, other vendors also traveled to Senegal where they could sell one bag (equivalent to a bag of 50 kg of rice) of baobab fruit (pulp-covered seeds separated from the fiber bundles) for 22,000 FCFA (37.19 USD) whereas the maximum price in Guinea-Bissau was 15,000 FCFA (25.36 USD). Likewise, vendors mentioned that a bag of Dialium guineense (husked pulp-covered seeds) was sold for 35,000 FCFA (59.16 USD) in Guinea-Conakry, while the same bag was priced at 15,000 FCFA (25.36 USD) in Guinea-Bissau. Figure 3 illustrates the general market pathways and actors involved in the trade of most wild edible plant products.

General depiction of the market pathways and actors involved in the trade of most wild edible plant products (a–c), for baobab fruit (a–d), and velvet tamarind fruit (e). The different arrow colors represent the place where the trade occurs. Note that it is common for collectors to involve other family or community members and that for palm oil, the fruit bundles are harvested by experienced male harvesters paid by women collectors

Implication of Formal Laws and Regulations

The DGFF, under the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MADR), is the body responsible for overseeing the implementation of the Forest Law (Decree-Law no. 5/2011). This Law recognizes that “complementary forest activities” such as gathering medicinal and edible plants, firewood, and beekeeping are governed according to the local relevant customary practices and norms. Likewise, the Protected Areas Law (Decree-Law no. 3/1997) allows for “gathering (…) activities recognized by the internal regulations of the Protected Areas for the exclusive benefit of the resident communities” in terms of household consumption in “zones of integral protection” and of commercialization in “zones of development” even if the demarcation of these zones remains unclear. Additionally, the Land Law (Decree-Law no. 5/98), which has only been enacted in 2018, defines the terms in which individuals and household resident in a given area are granted land use rights. Concerning the movement of goods from forests, the Forest Law mandates that “no forest product (…) may transit through any terrestrial, river, maritime, or aerial route without an appropriate transit guide issued by the DGFF, and the payment of applicabletaxes.” These taxes are determined by the MADR and the Ministry of Finance and collected by DGFF agents stationed at specific checkpoints. Accordingly, 60% of the tax revenue is channeled into the Forest Fund (Decree-Law no. 4-A/91), which, among others, intends to cover “forest restoration and conservation operations.” However, the practical application of these regulations is unclear, with undefined taxes, rules, and confusion regarding who has the authority to enforce them, whether it is the regional DGFF authorities or the National Guard. This ambiguity leads to vendors being subjected to arbitrary taxes at multiple checkpoints by unauthorized entities, significantly disrupting the trade of these products. According to vendors, they were required to pay 1,000 FCFA (1.69 USD) at each checkpoint for every product bag of 50 kg. Since all the markets are under the jurisdiction of the local urban council, vendors are also required to pay a daily fee of at least 100 FCFA (0.17 USD) to the local administration for access to a ground space or a wooden stall (Decree-Law no. 59/88). Additionally, they need to fulfil tax obligations to the General Directorate of Contributions and Taxes for their commercial activities.

Discussion

In this study, we report that 19 wild edible plant products from 12 species are being traded in the capital and the lumos in northern Guinea-Bissau. Catarino et al. (2019) previously identified leaf powder of baobab and Bombax costatum Mart. (not identified in this study) being marketed in Bissau city. It is possible that we did not find the latter because this species is rarer and its use is more localized than baobab leaf powder. Additionally, we have also observed petty traders selling fruits of Anisophyllea laurina R. Br. ex Sabine, Neocarya macrophylla (Sabine) Prance ex F.White (including separate seeds), Spondias mombin L., Uvaria chamae, Vitex doniana Sweet, and Xylopia aethiopica (Dunal) A. Rich. previously (pers. obs. by author LC). Apart from Uvaria chamae, the others are also noted as “being traded in the country markets” in Catarino and Indjai’s (2019) book of Bissau-Guinean trees. However, most of these fruits either have a short ripening period and are difficult to preserve (Anisophyllea laurina, Spondias mombin, Uvaria chamae, and Vitex doniana) or are sold and consumed in small quantities (Neocarya macrophylla and Xylopia aethiopica). This also explains why some wild edible plant products, sold fresh, were only found in the lumos. Given their characteristics, some of these products may not adequately reach the capital due to the lack of appropriate transportation and storage facilities (e.g., refrigerated).

Compared with other market studies of wild foods in West Africa, the number of species is similar: for instance, Gustad et al. (2004) identified 10 species in a weekly market in Cinzana (Mali), Nikiema (2005) recorded 16 species in Ouagadougou and Zoundweogo provinces (Burkina Faso), Schreckenberg (1999) identified 14 species in the Bassila region (Benin), and the same number was observed in Tambacounda and Kolda regions (Senegal) (Ba et al. 2006). All these studies highlighted the significant economic value of Shea nuts; however, this species seems to be very rare in Guinea-Bissau (CL and BI, pers. obs.). Most species observed in this study were also reported by other studies in West African countries; the exceptions were Parinari excelsa Sabine and Salacia senegalensis (Lam.) DC, which are primarily sourced in the wetter gallery forests in Guinea-Bissau and were not reported from these other studies focused on drier landscapes. However, Parinari excelsa was reported to be traded, e.g., in Sierra Leone (Jusu and Cuni-Sanchez 2017).

Overall, we found that prices were lower in lumos than in the capital city, which could be expected as these products were often sourced at lumos. Concerning the differences among products’ prices, those which require elaborated processing (e.g., netetu) or are difficult to find in the wild fetched higher prices. In Bissau city, the most expensive product was netetu, which also commands a high price in other West African markets (e.g., Gustad et al. 2004). The processing of African locust bean into netetu involves labor-intensive traditional techniques such as threshing, depulping, steaming, dehulling, separation, and fermentation. While it has historically been used as flavoring to prepare different dishes across several West African countries, in Bissau, as elsewhere, it is losing its popularity to some other cheaper industrial flavoring agents with very little nutritional value such as the well-known Maggi stock cubes (Nestlé). The highest-priced product in the lumos was the velvet tamarind fruit, primarily supplied by traders from Guinea-Conakry. This could be due to its limited availability within Guinea-Bissau, as it mainly grows in small patches of forest and gallery forest along riverbanks and floodplains (Catarino and Indjai 2019) and is commonly harvested for firewood and charcoal in West Africa (Ganglo et al. 2017). Notably, our study shows that the price for 1 kg of baobab leaf powder is nearly twice as much as the one reported by Catarino et al. (2019), supporting the vendors’ comments on increased prices for some NTFPs.

Baobab products stand out prominently with an annual retail value of 137 million FCFA (around 232,000 USD) for 185 vendors. This value is much higher than that reported from, e.g., Benin in 2006: 211 tons of baobab products generated 15.5 million FCFA (around 26,000 USD) for 139 rural households involved in the trade (Assogbadjo 2006). It should be noted that since baobab fruit pulp acceptance in 2008 as a novel food ingredient in the European Union and United States markets (Meinhold et al. 2022), Benin and Senegal have an established export industry of such products to Europe and the United States, but this is not the case in Guinea-Bissau, although baobab fruit pulp was reported to be traded to Senegal, from where it is exported to Europe. Therefore, it is expected that the total economic contribution of baobab products within the country is of much higher importance as intermediaries (often foreign traders from neighboring countries) also acquire large volumes directly in the villages. The total annual retail value estimated for all products from 331 vendors—418 million FCFA (707,000 USD)—means that one vendor could earn on average 2,100 USD per year from the sale of these products (although this is largely dependent on the position that the vendor occupies in the value chain), which is twice as much as the country GDP per capita (1,090 USD) (IMF 2024).

Vendors identified the natural woodlands as the main source of all wild edible plants traded. These woodlands are mainly communal and governed by customary laws. However, in some cases, it is unclear whether they are referring to natural woodlands or fallow land. Other studies in West African drylands highlight that fallow areas play a key role in providing many species yielding important NTFPs (Gausset et al. 2005; Schreckenberg 1999; Schumann et al. 2011).

The harvesting of wild edible plants is primarily carried out by women, whether individually or as part of small family or community operations. In Guinea-Bissau, women’s involvement extends beyond just collection; they also play a dominant role in processing, transportation, and retailing, mirroring the broader pattern seen in West Africa’s wild edible plant trade (e.g., Fandohan et al. 2010). However, moving downstream in the value chain, women’s decision-making power diminishes, limiting their control over the productive process and associated benefits. This heightens the risk of their roles being eroded as the value of some of these NTFPs rises. Notably, there is a discernible trend of increased male involvement in traditionally women-dominated value chains as soon as they become more profitable, such as the eru (Gnetum africanum Welw.) and the bush mango (Irvingia gabonensis (Aubrey-Lecomte. ex O’Rorke.) Baill.) in Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, for example (Ingram et al. 2014). In Morocco, the argan oil trade (Argania spinosa (L.) Skeels) has shifted from women’s cooperatives into intermediaries that supply larger corporations (Montanari et al. 2023). It is important to emphasize that, unlike vendors in Bissau city who can readily switch between selling cultivated and wild products, the sale of wild products in the lumos constitutes one of the few off-farm activities that women in rural areas engage in as a safety net. Therefore, it is imperative to ensure that the diversification opportunities arising from the trade of these products, particularly those linking rural areas to international markets, do not keep women in a low-return activity or, ultimately, exclude them from the productive process.

In Guinea-Bissau, once the product is collected, two primary commercial pathways for wild edible plants occur: one involving the flow of products to the markets in the capital city and the other catering to cross-border export markets. While the former operates through short market chains, with collectors in the lumos doubling as traders and supplying Bissau retailers who then directly sell to urban consumers, the complexity of the latter was not fully understood in this study. However, it became evident from our interviews that the development of new export markets for certain products such as baobab and Saba senegalensis fruits in neighboring economies has brought significant changes in the market structure and functioning within Guinea-Bissau. In recent years, new actors, who swiftly capture the resources at the start of the season, entered the scene, sometimes interacting with the farmers in the villages or directly harvesting the products in lands not recognized by formal institutions but that might be subjected to customary rules and norms. By putting more focus on the trade activity away from the subsistence role and releasing natural resources that can be exploited by external actors, this shift not only diminishes human-nature connectedness, which is believed to be at the forefront of pro-environmental behaviors (Ives et al. 2018), but also transfers value from the production location to the location where the value is realized. Similar patterns have been observed for other NTFPs in Africa, such as the abovementioned Shea butter in Burkina Faso (Gausset et al. 2005) and the argan oil in Morocco (Meagher 2019) or the devil’s claw (Harpagophytum spp.) in Namibia (Lavelle 2023). Therefore, future research and discussions should explore the effects of spatial configurations in global and regional production networks of wild products, including their impacts on uneven distributions that may hinder regional development. In Guinea-Bissau, such understanding is also important to monitor the social and environmental outcomes of the implementation of the Land Law. In support of its implementation, an ongoing participatory process has been mapping the territories of the rural villages across the country. However, it is important to note the risk of classifying unmapped areas as “vacant,” possibly exposing them to the extraction of NTFPs or other natural resources by external actors (Tsing 2005). Ultimately, as the population increases (2.2% yearly, World Bank estimate for 2022) and wild edible plant products are harvested not only to respond to the increasing market demand (both nationally and internationally) but also for household consumption in the villages where these products are collected, it is reason to believe that the sustainability of wild edible plants trade in Guinea-Bissau will deteriorate. This risk is further exacerbated by the persisting deforestation for cashew plantations. Despite the fact that most traded products belong to species classified as least concern according to the IUCN Red List, others are yet to be assessed (e.g., Adansonia digitata and Saba senegalensis). Also, although the present study does not present biological data on stocks or yields, preventing a direct assessment of the sustainability of wild plant harvests, our results on traded volumes combined with the hints given by the vendors during the interviews on the reduced availability of most traded species in the wild suggest that some species might be becoming scarce in some areas. Fruit and leaf harvesting can have significant impacts on a species’ population (e.g., intensive harvesting of leaves may reduce flowering and fruiting), but they are unlikely to have the same negative impacts on a species population structure as uses that involve more destructive harvesting (e.g., collection of fibers, roots, bark, firewood) (Ticktin 2004). However, some of the wild edible plants traded found in our study have additional uses that involve destructive techniques, such as the collection of firewood from African locust bean and velvet tamarind.

Implications of the Study Findings

While international demand is difficult to foresee, local demand for wild edible plant products is likely to persist in the long term as they are deeply rooted in Bissau-Guinean cultural heritage, with various products incorporated into traditional cuisine. Trade circuits to the capital city continue to exist even if the species’ local availability is limited, as seen with velvet tamarind fruit, highlighting their importance in the country’s consumption patterns. The endurance of these cultural foodways is also evident among the diaspora. For example, Bissau-Guinean women were observed selling baobab ice lollies in Rossio (an area in Lisbon’s historic center where informal exchange of goods among migrant communities is held despite police controls) (Abranches 2013). Additionally, rural and urban people in sub-Saharan Africa perceive the health benefits of consuming locally sourced wild food products. In Mozambique, the domestic market for baobab fruits experienced a noteworthy increase during the COVID-19 pandemic primarily driven by this health benefit perception (Krauss et al. 2023). Similarly, urban markets in Ghana have experienced rising demand for netetu due to an increased awareness of its health advantages (Lelea et al. 2022). Cultural norms and the integration of wild edible plants into local land management decisions and practices also reflect their importance to Bissau-Guineans. Trees of wild edible species are among the few spared by farmers when establishing new cashew orchards (Temudo et al. 2015), and customary laws shaped by complex social factors (e.g., kinship, ethnicity, religious and spiritual beliefs) extend not only to land but also to individual wild trees (Frazão-Moreira 2009; Temudo and Bivar 2014). Hence, prioritizing the ecological sustainability of wild edible plants products is paramount to ensure that their local trade continues to provide meaningful livelihoods.

Building up on local values and practices is, arguably, the most effective way of fostering sustainable behaviors (Altieri 2004). Therefore, land management interventions should be as comprehensive to prioritize the development of local-adapted protective measures for the wild populations of culturally important species (especially those that are traded in larger quantities, such as African locust bean, baobab, and oil palm; have narrower distribution ranges within the country such as velvet tamarind; or have multiple uses) and of alternative production systems for livelihood benefits as “environmentally friendly” as possible (e.g., through agroecological approaches, namely, agroforestry). Identification and monitoring of harvesting practices that promote species population persistence are also key. For this to succeed, it is crucial to reverse the broader disabling institutional and political environment that hinders the environmental sustainability of the NTFP sector in the country (e.g., lack of forest management strategies, absence of NTFP-oriented policies, ungrounded taxes, focus on the cashew sector as the only means of economic growth). Likewise, better cooperation between ECOWAS member states regarding wild forest product exploitation and trade policy, along with enhanced traceability in international commodity supply chains, is needed. This is critical to prevent resource depletion resulting from increased trade and demand displacement, but also to guarantee that upstream actors in the NTFP value chains sufficiently capture the associated economic benefits.

Wells et al. (2023) show that well-being contributions from wild resources are generally enhanced with access to infrastructure, markets, and other household capitals. Thus, supporting indirect institutions such as transportation connections, selling and storage market infrastructure, and sanitary conditions but also capacity-building and business development could improve local assets and potentially lead to more inclusive regional development (Rodríguez-Pose 2013). Such support is especially relevant for women as they play a dominant role in the entire value chain of these products. Female vendors in Guinea-Bissau may encounter additional financial opportunities as new trade networks for wild edible plants emerge, but they lack essential human and social assets to fully capitalize on these prospects and improve their livelihoods. While they perceive market trends, they face challenges in accessing vital market information, such as prices, distribution channels, demand levels, and quality standards. This lack of information hampers their ability to make informed decisions about when and where to sell their products, further weakening the already limited bargaining power, particularly if resources become scarce and competitive. To enhance their market opportunities, female vendors could potentially benefit from improved linkages to wider networks through social cooperation, broader civic engagement, and participation in added value and high-quality certification processes. As an example, a study in Mozambique (Krauss et al. 2023) shows that livelihood diversification into commercialization of baobab products has been a lifeline for women in rural areas but it was only after an alliance between a social enterprise co-managed by women collectors and like-minded institutional donors that safeguarded this livelihood under COVID-19 non-pharmaceutical interventions.

Study Limitations and Future Research

This study provides the first available estimates for wild edible plant product trade in Guinea-Bissau. However, our study approach had two important limitations. Firstly, we only interviewed market vendors in the country’s capital and some lumos, which means that our estimates might be on the lower end of what is traded across the country. We potentially missed the trade occurring in the villages with the involvement of intermediaries (see Fig. 3). Secondly, to accurately assess the ecological sustainability of the wild edible plant product trade, vendors’ perceptions of abundance change should be complemented with field observations of, e.g., species’ abundance and regeneration in the wild. Therefore, future research should gather more information on these aspects, as well as on harvesting techniques used to gather such products. Additionally, it is important to clarify in future research the source habitat of these products (e.g., natural woodland or other land covers), especially given the rapid transformation of traditional shifting cultivation systems into permanent cashew orchards and the broader changes in land tenure regimes from customary and communal to statutory and privatized (Temudo et al. 2015).

Conclusion

In this study, we show that the trade of wild edible plants in the capital and northern Guinea-Bissau markets is dominated by dry plant products from African locust bean, baobab, and velvet tamarind, and others like palm oil and palm fruit. This trade, dominated by women who harvest these products themselves, carries a substantial estimated annual retail value of at least 418 million FCFA (707,000 USD) for a volume of 354 metric tons (tonnes) (plus 71,000 L of palm oil). Such products are primarily destined for either the capital city or cross-border commerce and have been experiencing increased demand fueled by the development of export markets and increased urban consumption. Since most of the products sold are the fruit part of the plant, it offers indications that the products can be sustainably harvested. However, in the context of no effective regulatory frameworks for both exploitation and trade, this surge in demand may have implications on the local ecological sustainability of the wild populations, namely, of Adansonia digitata, Dialium guineense, and Parkia biglobosa. Additionally, while it offers potential additional financial gains for some, it simultaneously risks the security of women’s livelihood strategy due to the growing involvement of external actors in both harvesting and retailing. Our results suggest that preserving wild plant populations and the local, traditional trade that has long been a safety-net to rural Bissau-Guineans while tapping into more profitable market channels requires a focus on national and international policy reforms that build on sustainable land management practices and elevate the importance of wild edible plants through operative governance and institutional structures. Pivotal is the social protection of women’s roles and rights in NTFPs’ value chains and the strengthening of their collective bargaining power.

References

Abranches, M. 2013. Transnational informal spaces connecting Guinea-Bissau and Portugal: Food, markets and relationships. Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development 42(3/4): 333–375.

Altieri, M. A. 2004. Linking ecologists and traditional farmers in the search for sustainable agriculture. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 2(1): 35–42. https://doi.org/10.2307/3868293

Angelsen, A., P. Jagger, R. Babigumira, B. Belcher, N. J. Hogarth, S. Bauch, J. Börner, C. Smith-Hall, and S. Wunder. 2014. Environmental income and rural livelihoods: A global-comparative analysis. World Development 64: S12–S28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.03.006

Assogbadjo, A. E. 2006. Importance socio-économique et étude de la variabilité écologique, morphologique, génétique et biochimique du baobab (Adansonia digitata L.) au Bénin. Ghent University, Belgium: PhD Dissertation

Assogbadjo, A., R. G. Kakaï, F. Vodouhê, C. Djagoun, J. Codjia, and B. Sinsin. 2012. Biodiversity and socioeconomic factors supporting farmers’ choice of wild edible trees in the agroforestry systems of Benin (West Africa). Forest Policy and Economics 14(1): 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2011.07.013

Ba, C., J. Bishop, M. Deme, H. D. Diadhiou, and A. B. Dieng 2006. The economic value of wild resources in Senegal: a preliminary evaluation of non-timber forest products, game and freshwater fisheries. Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK: IUCN Switzerland and UK.

Belcher, B., M. Ruiz-Pérez, and R. Achdiawan. 2005. Global patterns and trends in the use and management of commercial NTFPs: Implications for livelihoods and conservation. World Development 33(9): 1435–1452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.10.007

Catarino, L., and B. Indjai. 2019. Árvores florestais da Guiné-Bissau. Bissau, Guiné-Bissau: Instituto da Biodiversidade e Áreas Protegidas.

Catarino, L., E. Martins, M. Basto, and M. Diniz. 2008. An annotated checklist of the vascular flora of Guinea-Bissau (West Africa). Blumea 53(1): 1–222. https://doi.org/10.3767/000651908X608179

Catarino, L., Y. Menezes, and R. Sardinha. 2015. Cashew cultivation in Guinea-Bissau–risks and challenges of the success of a cash crop. Scientia Agricola 72: 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-9016-2014-0369

Catarino, L., M. M. Romeiras, Q. Bancessi, D. Duarte, D. Faria, F. Monteiro, and M. Moldão. 2019. Edible leafy vegetables from West Africa (Guinea-Bissau): Consumption, trade and food potential. Foods 8(10): 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods8100493

Chambers, R., and M. Leach 1987. Trees to meet contingencies: Savings and security for the rural poor. ODI Social Forestry Network Paper 5a, London, UK.

Coelho, F. L. 1953. Duas descrições seiscentistas da Guiné 1669–1684. Lisboa, Portugal: Academia Portuguesa da História.

d’Almada, A. A. 1594. Tradado breve dos rios de Guiné do Cabo-Verde: desde o rio do Sanag ́até aos baixos de Sant’Anna. Porto, Portugal: Typographia Commercial Portuense.

De Beer, J. H., and M. J. McDermott 1989. The economic value of non-timber forest products in Southeast Asia: With emphasis on Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand. Amsterdam, Netherlands: IUCN Netherlands.

de Mello, N. G. R., H. Gulinck, P. Van den Broeck, and C. Parra. 2020. Social-ecological sustainability of non-timber forest products: A review and theoretical considerations for future research. Forest Policy and Economics 112: 102109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2020.102109

Djagoun, C. A. M. S., S. Zanvo, E. A. Padonou, E. Sogbohossou, and B. Sinsin. 2022. Perceptions of ecosystem services: A comparison between sacred and non-sacred forests in central Benin (West Africa). Forest Ecology and Management 503: 119791. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119791

Donelha, A., and P. Hair. 1977. Descrição da Serra Leoa e dos rios de Guiné do Cabo Verde. Lisboa, Portugal: Junta de Investigações Científicas do Ultramar.

Fandohan, B., A. E. Assogbadjo, R. G. Kakaï, T. Kyndt, E. De Caluwé, J. T. C. Codjia, and B. Sinsin. 2010. Women’s traditional knowledge, use value, and the contribution of Tamarind (Tamarindus indica L.) to rural households’ cash income in Benin. Economic Botany 64(3): 248–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12231-010-9123-2

FAO 2023. FAOSTAT statistical database. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data (03 February 2024).

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, and WHO 2023. The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2023: urbanization, agrifood systems, transformation and healthy diets across the rural-urban continuum. Rome: FAO.

Frazão-Moreira, A. 2009. Plantas e “pecadores”: Percepções da natureza em África. Lisboa, Portugal: Livros Horizonte.

Freudenberger, M. S., J. A. Carney, and A. R. Lebbie. 1997. Resiliency and change in common property regimes in West Africa: The case of the tongo in the Gambia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone. Society & Natural Resources 10(4): 383–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941929709381036

Ganglo, J. C., G. K. Djotan, J. A. Gbètoho, S. B. Kakpo, A. K. Aoudji, K. Koura, and R. Y. Tessi. 2017. Ecological niche modeling and strategies for the conservation of Dialium guineense Willd. (Black velvet) in West Africa. International Journal of Biodiversity and Conservation 9(12): 373–388. https://doi.org/10.5897/IJBC2017.1151

Gausset, Q., E. L. Yago-Ouattara, and B. Belem. (2005). Gender and trees in Péni, South-Western Burkina Faso. Women’s needs, strategies and challenges. Geografisk Tidsskrift-Danish Journal of Geography 105(1): 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167223.2005.10649527

GoGB (Government of Guinea-Bissau). 2021. Updated Nationally Determined Contribution in the Framework of the Paris Climate Agreement. https://www.undp.org/guinea-bissau/publications/updated-nationally-determined-contribution-framework-paris-climate-agreement (10 May 2024)

Gustad, G., S. S. Dhillion, and D. Sidibe. 2004. Local use and cultural and economic value of products from trees in the parklands of the municipality of Cinzana, Mali. Economic Botany 58(4): 578–587. https://doi.org/10.1663/0013-0001(2004)058[0578:LUACAE]2.0.CO;2

Heubach, K., R. Wittig, E.-A. Nuppenau, and K. Hahn. (2011). The economic importance of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) for livelihood maintenance of rural west African communities: A case study from northern Benin. Ecological Economics 70(11): 1991–2001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.05.015

IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2015. Guinea-Bissau, Country Report No. 2015/195. Washington, D.C: IMF.

IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2022. Guinea-Bissau, Country Report No. 2022/042. Washington, D.C: IMF

IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2023. Guinea-Bissau, Country Report No. 2023/403. Washington, D.C: IMF.

IMF (International Monetary Fund). (2024). World Economic Outlook Database. www.imf.org/external/datamapper/datasets/WEO (15 April 2024).

Ingram, V., J. Schure, J. C. Tieguhong, O. Ndoye, A. Awono, and D. M. Iponga. (2014). Gender implications of forest product value chains in the Congo basin. Forests, Trees and Livelihoods 23(1-2): 67-86. https://doi.org/10.1080/14728028.2014.887610

ISE (International Society of Ethnobiology). 2006. International Society of Ethnobiology Code of Ethics (with 2008 additions). http://ethnobiology.net/code-of-ethics/ (04 April 2022).

Ives, C. D., D. J. Abson, H. Von Wehrden, C. Dorninger, K. Klaniecki, and J. Fischer. 2018. Reconnecting with nature for sustainability. Sustainability science 13: 1389–1397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0542-9

Jusu, A., and A. Cuni-Sanchez. 2017. Priority indigenous fruit trees in the African rainforest zone: Insights from Sierra Leone. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 64(4): 745–760. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-016-0397-9

Krauss, J. E., E. Castro Jr, A. Kingman, M. Nuvunga, and C. Ryan. 2023. Understanding livelihood changes in the charcoal and baobab value chains during Covid-19 in rural Mozambique: The role of power, risk and civic-based stakeholder conventions. Geoforum 140: 103706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2023.103706

Lavelle, J. J. 2023. An analysis of access in Devil’s Claw (Harpagophytum Spp.) harvesting and trade in Namibia. Society & Natural Resources 36(11): 1398–1417. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2023.2228231

Lelea, M. A., L. M. Konlan, R. C. Ziblila, L. E. Thiele, A. Amo-Aidoo, and B. Kaufmann. 2022. Strategies to promote sustainable development: The gendered importance of addressing diminishing African Locust Bean (Parkia biglobosa) resources in northern Ghana’s agro-ecological landscape. Sustainability 14(18): 11302. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811302

Leßmeister, A. 2017. Vegetation changes and their consequences for the provisioning service of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) in a West African savanna. [PhD thesis, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main].

Lourenço-Lindell, I. 1995. The informal food economy in a peripheral urban district: The case of Bandim District, Bissau. Habitat International 19(2): 195-208. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-3975(94)00066-B

Meagher, K. 2019. Working in chains: African informal workers and global value chains. Agrarian South: Journal of Political Economy 8(1–2): 64–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/2277976019848567

Meinhold, K., and D. Darr. 2022. Keeping up with rising (quality) demands? The transition of a wild food resource to mass maket, using the example of Baobab in Malawi. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 6: 840760 https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2022.840760

Meinhold, K., W. K. Dumenu, and D. Darr. 2022. Connecting rural non-timber forest product collectors to global markets: The case of baobab (Adansonia digitata L.). Forest Policy and Economics 134:102628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2021.102628

Meyfroidt, P., E. F. Lambin, K.-H. Erb, and T. W. Hertel. 2013. Globalization of land use: Distant drivers of land change and geographic displacement of land use. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 5(5): 438–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.04.003

Montanari, B., M. Handaine, and J. Id Bourrous. 2023. Argan oil trade and access to benefit sharing: A matter of economic survival for rural women of the Souss Massa, Morocco. Human Ecology 51(5): 995–1007. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-023-00453-6

Moritz, M., B. R. Kyle, K. C. Nolan, S. Patrick, M. F. Shaffer, and G. Thampy. 2009. Too many people and too few livestock in West Africa? An evaluation of Sandford’s thesis. The Journal of Development Studies 45(7): 1113–1133. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380902811058

Nabaloum, A., D. Goetze, A. Ouédraogo, S. Porembski, and A. Thiombiano. 2022. Local perception of ecosystem services and their conservation in Sudanian savannas of Burkina Faso (West Africa). Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 18(1): 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-022-00508-w

Naughton, C. C., T. F. Deubel, and J. R. Mihelcic. 2017. Household food security, economic empowerment, and the social capital of women’s shea butter production in Mali. Food Security 9: 773-784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-017-0706-y

Nikiema, A. 2005. Agroforestry parkland species diversity: Uses and management in semi-arid West-Africa (Burkina Faso) [PhD Thesis, Wageningen University].

Pérez, M. R., O. Ndoye, A. Eyebe, and D. L. Ngono. 2002. A gender analysis of forest product markets in Cameroon. Africa today 49(3): 97–126. https://doi.org/10.1353/at.2003.0029

Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2013. Do institutions matter for regional development? Regional studies 47(7): 1034-1047. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.748978

Rousseau, K., D. Gautier, and D. A. Wardell. 2015. Coping with the upheavals of globalization in the shea value chain: The maintenance and relevance of upstream shea nut supply chain organization in western Burkina Faso. World Development 66: 413–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.09.004

Schreckenberg, K. 1999. Products of a managed landscape: Non‐timber forest products in the parklands of the Bassila region, Benin. Global Ecology and Biogeography 8(3–4): 279–289. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1466-822X.1999.00129.x

Schumann, K., R. Wittig, A. Thiombiano, U. Becker, and K. Hahn. 2011. Impact of land-use type and harvesting on population structure of a non-timber forest product-providing tree in a semi-arid savanna, West Africa. Biological Conservation 144(9): 2369–2376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2011.06.018

Segnon, A. C., and E. G. Achigan-Dako. 2014. Comparative analysis of diversity and utilization of edible plants in arid and semi-arid areas in Benin. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 10(1): 80. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-10-80

Shackleton, C., and A. de Vos. 2022. How many people globally actually use non-timber forest products? Forest Policy and Economics 135: 102659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2021.102659

Shackleton, S., P. Shanley, and O. Ndoye. 2007. Invisible but viable: Recognising local markets for non-timber forest products. International Forestry Review 9(3): 697–712. https://doi.org/10.1505/ifor.9.3.697

Shackleton, C., C. Delang, S. Shackleton, and P. Shanley. 2011. Non-timber forest products: Concept and definitions. In Non-timber forest products in the global context, eds. S. Shackleton, C. Shackleton, & P. Shanley, 3–21. Berlin, Germany: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Spínola, A. 1972. Prospectiva do desenvolvimento económico e social da Guiné. Lisboa, Portugal: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar.

Sunderland, T., R. Achdiawan, A. Angelsen, R. Babigumira, A. Ickowitz, F. Paumgarten, V. Reyes-García, and G. Shively. 2014. Challenging perceptions about men, women, and forest product use: A global comparative study. World Development 64: S56-S66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.03.003

Temudo, M. P., and M. B. Abrantes. 2013. Changing policies, shifting livelihoods: The fate of agriculture in Guinea‐Bissau. Journal of Agrarian Change 13(4): 571-589. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0366.2012.00364.x

Temudo, M., and M. Bivar. 2014. The cashew frontier in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa: Changing landscapes and livelihoods. Human Ecology 42: 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-014-9641-0

Temudo, M. P., R. Figueira, and M. Abrantes. 2015. Landscapes of bio-cultural diversity: Shifting cultivation in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. Agroforestry Systems 89(1): 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-014-9752-z

Temudo, M. P., D. Oom, and J. M. Pereira. 2020. Bio-cultural fire regions of Guinea-Bissau: Analysis combining social research and satellite remote sensing. Applied Geography 118: 102203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2020.102203.

Ticktin, T. 2004. The ecological implications of harvesting non‐timber forest products. Journal of Applied Ecology 41(1): 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2004.00859.x

Tsing, A. L. 2005. Friction: An ethnography of global connection. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

van der Ploeg, J. 1990. Autarky and technical change in rice production in Guinea Bissau: on the importance of comoditisation and decommoditisation as interrelated processes. In Rural households in emerging societies: Technology and change in sub-Saharan Africa, eds. M. Haswell & D. Hunt, 171-195. Oxford: Berg Published Ltd.

Wardell, D. A., A. Tapsoba, P. N. Lovett, M. Zida, K. Rousseau, D. Gautier, M. Elias, and T. Bama. 2021. Shea (Vitellaria paradoxa CF Gaertn.)–the emergence of global production networks in Burkina Faso, 1960–2021 1. International Forestry Review 23(4): 534–561. https://doi.org/10.1505/146554821834777189

Wells, G. J., C. M. Ryan, A. Das, S. Attiwilli, M. Poudyal, S. Lele, K. Schreckenberg, B. E. Robinson, A. Keane, and K. M. Homewood. 2023. Hundreds of millions of people in the tropics need both wild harvests and other forms of economic development for their well-being. One Earth 7(2): 311-324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2023.12.001

Wunder, S., A. Angelsen, and B. Belcher. 2014. Forests, livelihoods, and conservation: Broadening the empirical base. World Development 64: S1-S11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.03.007

Wynberg, R., S. Laird, J. Van Niekerk, and W. Kozanayi. 2015. Formalization of the natural product trade in southern Africa: Unintended consequences and policy blurring in biotrade and bioprospecting. Society & Natural Resources 28(5): 559–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2015.1014604

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to our study participants, who graciously shared their time with us. Our thanks extend to our colleagues Quintino Bancessi and Claudia Tavares for their assistance in Guinea-Bissau, as well as Lea Christin Huber for her important insights on this manuscript. Finally, we thank two anonymous reviewers for their comments which helped improve our manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Norwegian University of Life Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leite, A., Westengen, O., Catarino, L. et al. From the Wild to the Market: The Trade of Edible Plants in Guinea-Bissau. Econ Bot (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12231-024-09614-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12231-024-09614-0