Summary

Praxelis cleggiae (Compositae: Eupatorieae: Praxeliinae) is described and illustrated from the granite inselbergs (upon which it is most common), and on road crown chippings on old roads, in the Departamento de Santa Cruz, Bolivia; it has a disjunct distribution and is also found on the Serranía San Simón, in the San Ignacio Schist belt, Departamento de Beni. Material of this species was mostly determined as P. insignis (Malme) R.M.King & H.Rob., a Brazilian species, described from the metamorphosed sandstone of what is now the Parque Nacional da Chapada dos Guimarães in Mato Grosso State. The two species have some superficial resemblance, but differ significantly in plant size, internode length (relative to leaf length), branching, leaf shape and size, phyllaries, achenes and pappus. The total number of species of Praxelis recognised in Bolivia is now seven, and 20 species in the genus worldwide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During the first author’s introductory, whistle-stop, tour of Bolivia in 2008, with John R. I. Wood and a variety of his project students, some time was spent in the region of Concepción, Provincia Ñuflo de Chavez, in the east of the Departamento de Santa Cruz. John Wood had been keen on introducing the granite inselbergs, forming part of the Bolivian portion of the Guaporé Shield (Jones 1985) (the eastern Bolivian portion of the Brazilian Precambrian Shield formation), and indeed stimulating the first author’s interest in their flora (Hind 2014a). The three types of ‘rock islands’, lajas (= rock slabs) (Fig. 2B, albeit flooded), shield (or whale-back) (Fig. 1B, 2A) and dome inselbergs often occur together. Rarely, extensive shield inselbergs have flattened tops, are largely submerged in the surrounding forest, and have been nicknamed as DODOs (Drive-On-Drive-Off) by the first author, since dirt roads crossing them continue from the forest straight onto the surface and merge with the forest at the far end — the central portion of the outcrop often dropping many metres off into the forest (Fig. 1A, B). They frequently form complexes (that the first author has simply called ‘archipelagos’ within the ‘sea’ of the Bosque Seco Chiquitano (= Chiquitano Dry Forest). These are sometimes referred to as ‘island-like systems’ (ILS), complexes of which form archipelago-like systems within a matrix (Itescu 2019), of the Bosque Seco Chiquitano. The inselbergs appear to be ideal habitats for an increasingly recognised number of endemics (e.g. see Ibisch et al. 1995; Mamani et al. 2010; Hind 2014a; Hind & Frisby 2014). A number of collections were made, including several Compositae, amongst which was a species of Praxelis Cass. (Compositae: Eupatorieae: Praxeliinae) that has since proven of some interest (see Specimens Examined below).

A Habitat, showing edge of a DODO (= Drive-On-Drive-Off) inselberg, part of an inselberg complex including an adjacent whaleback inselberg, with disturbed Chiquitania woodland adjacent the road; B Habitat, showing large, relatively long-lived seasonal/temporary pool on top of a shallow whaleback/shield inselberg, with a large colony of Praxelis cleggiae in the foreground. Between San Antonio de Lomerío and Concepción, Prov. Ñuflo de Chavez, Depto. de Santa Cruz, Bolivia. photos © D. J. NICHOLAS HIND.

A Habitat view of part of a whaleback inselberg with larger plant mat with anchoring tree, and bromeliad core, together with a large colony of Praxelis cleggiae, cerioid cactus and shrubby legume — and J. R. I. Wood in the background. Between San Antonio de Lomerío and Concepción, Prov. Ñuflo de Chavez, Depto. de Santa Cruz, Bolivia. photo courtesy of the project ‘conservation of cerrados in eastern bolivia’; B Part of a large colony of Praxelis cleggiae, with its conspicuous red stem, in flooded area over a large rock slab adjacent to road to the far south of Concepción, Prov. Ñuflo de Chavez, Depto. de Santa Cruz, Bolivia. photo © D. J. NICHOLAS HIND.

A subsequent visit, in 2016, revealed more localities, most either on, or linked to, the granitic inselbergs outcrops (mostly within the Provincia Ñuflo de Chavez). These, together with earlier collections from the Provincia Velasco, and one disjunct locality on the Serranía San Simón, in the southeastern corner of the Departamento Beni in what is referred to as the San Ignacio Schist belt (see Biste et al. 1991), proved to be a taxon of interest. It is most frequently seen in damper situations, either in temporarily flooded road margins (Fig. 3B), alongside temporary pools on the lajas (Fig. 1B) or in the surrounding cerrado-like vegetation, and exceptionally, the species was found on ‘grassed over’ road crowns (often of chippings or semi-compacted ‘gravel’) common on infrequently used roads, growing amongst the cascalho solto (Port. = loose gravel) or gravilla suelta (Span.), especially in the area around El Cerrito, Provincia Ñuflo de Chavez, although broadly, all associated with granite outcrops.

A detail of colony of Praxelis cleggiae at margin of plant mat adjacent to Bromeliaceae (r), xerophytic ferns, and the short grass vegetation towards the edge of the mat (l) — large machete for comparison. Between San Antonio de Lomerío and Concepción, Prov. Ñuflo de Chavez, Depto. de Santa Cruz, Bolivia. photo © d. j. nicholas hind; B large plant of Praxelis cleggiae (showing ascending habit of young plant) on margin of plant mat on whale back inselberg. Between San Antonio de Lomerío and Concepción, Prov. Ñuflo de Chavez, Depto. de Santa Cruz, Bolivia. photo courtesy of the project ‘conservation of cerrados in eastern bolivia’.

Initial field observations of the achenes were confirmed back in the herbarium, that the achenes were strongly obcompressed and only possessed two lateral, pale setuliferous margins, the inner (adaxial) surface scarcely angled, in a best-fit manner, between those of the next two inner florets, and certainly not ribbed; the abaxial surface is merely rounded. In this case, obcompressed can be defined as ‘compressed in the opposite direction to usual’ (i.e. dorsiventrally, or from front to back, rather than flattened from top to bottom), a condition met with throughout the family, with examples found in Praxelis and in genera such as Barroetea A.Gray (Eupatorieae), Eupatoriopsis Hieron. (Eupatorieae), Dipterocypsela S.F.Blake (Vernonieae), Heterocypsela H.Rob. (Vernonieae), Lulia Zardini (Mutisieae), Phyllocephalum Blume (Vernonieae), Verbesina L. (Heliantheae), Welwitschiella O.Hoffm. (Astereae), etc.

The subtribe Praxeliinae are most easily recognised, at least amongst the Bolivian taxa (Chromolaena DC., Praxeliopsis G.M.Barroso and Praxelis), by their imbricate phyllaries that are totally deciduous after achene loss (but appressed and not spreading before loss), predominantly 5-ribbed prismatic (rarely biconvex or obcompressed) achenes possessing a distinct carpopodium, and uniseriate, capillary, barbellate pappus setae (these usually numerous, rarely reduced to 5 in Praxeliopsis) (King & Robinson 1987; Hind & Robinson 2006; Hind 2014b).

Unfortunately, there are somewhat contrasting concepts of key characters distinguishing the subtribe, not least in the persistence of the phyllaries. Christ & Ritter (2019: 143) stated that within the subtribe the phyllaries were ‘deciduous, caducous, or not’, and Abreu (2015, 2020) stated that the phyllaries in Praxelis were caducous or persistent, in complete contrast to accepted dogma. Caducous elements of plants, in the sense that they fall soon after formation, and certainly before maturity, such as pappus setae in many members of the Compositae tribe Vernonieae subtribe Lychnophorineae, are well known (e.g. Loeuille et al. 2019), although possibly misinterpreted as deciduous (e.g. Robinson 1999, 2006b: 161; Keeley & Robinson 2009: 451 — as ‘easily deciduous’). Caducous phyllaries in the tribe Eupatorieae subtribe Praxeliinae are unknown, and in discussing the subtribe, King & Robinson (1987: 379) indicated that exceptions to the deciduous rule were relatively few (e.g. Eupatoriopsis hoffmannii Hieron., and few examples in Chromolaena DC., where some phyllaries, usually the outer, are persistent).

Teles et al. (2016) indicated that members of the subtribe were characterised by the ‘completely deciduous imbricate involucral bracts (except two species of Praxelis), ...’; these species were unspecified. Abreu et al. (2014) stated that in Praxelis, amongst other characters, the genus could be distinguished by the ‘deciduous involucre’, yet later, Abreu (2015) and Abreu & Esteves (2017: 78) keyed out Brazilian species of Praxelis upon the basis of persistent or deciduous phyllaries in their first key couplet; six species were considered to have persistent phyllaries. However, this was most probably based on inadequate observation and understanding of the relevant protologues. Examination of historical material of Praxelis decumbens (Gardner) Teles & R.Esteves has shown that Riedel 170 (the most likely basis of the widespread distribution ‘Martius Herb. Fl. Bras. 814’) has deciduous phyllaries; similarly type material of Praxelis sanctopaulensis (B.L.Rob.) R.M.King & H.Rob. also has deciduous phyllaries (although oddly still keying out in Ribeiro et al. (2021: 1137) as ‘involucral bracts non-caducous’), and; type material of Eupatorium kleinioides Kunth var. latifolium Chodat (as a synonym of P. grandiflora (DC.) Sch.Bip.) also has deciduous involucres. Praxelis splettii H.Rob. (Robinson 2006a: 148) was described as having ‘involucral bracts reddish, imbricate and appressed, all deciduous, ...’. Type material of Praxelis insignis (Malme) R.M.King & H.Rob. and Praxelis macrocarpa V.Abreu & R.Esteves clearly possesses relatively juvenile capitula lacking mature achenes, and therefore unlikely to offer signs of deciduous phyllaries. Christ & Ritter (2019) stated that the phyllaries were ‘completely deciduous during the maturity of the cypselas — apparently quoting King & Robinson (1987), although King & Robinson (1987: 379) merely stated ‘totally deciduous’, later noting that the ‘primary characteristic of the Praxelinae [sic!] is the totally deciduous involucre, the bracts falling rather than spreading at maturity.’ However, they did note that it was a ‘particularly useful feature in herbarium specimens, but is useless in the field, ...’, something the authors of the current paper consider untrue.

Hind (2014b: 1) provided a useful table of selected characters separating Chromolaena and Praxelis. Praxelis, a genus currently of 20 species (cf. King & Robinson 1987; Hind & Robinson 2006; Hind 2014b; Hind & Frisby 2015) has campanulate capitula, possessing 3 – 4-seriate phyllaries, a conical, epaleaceous receptacle, balusterform anther collars, slightly to strongly obcompressed achenes with sparsely setuliferous bodies, and a distinctive asymmetrical carpopodium. The Bolivian species recognised so far (Hind 2011; Robinson 2014; Hind 2014b) fall into two groups: annuals, and perennials (often with xylopodiaceous rootstocks). The collections mentioned above fall into the latter group, although rarely collected with the complete rootstock. Hind (2014b) noted that there were issues with some of the more recent collections. Only two are now considered to be Praxelis chiquitensis (B.L.Rob.) R.M. King & H.Rob., six others were mentioned and these ‘agreed well with Malme’s Eupatorium insigne, now Praxelis insignis (Malme) R.M.King & H.Rob.’ However, a critical re-examination of this material has been necessary in an attempt to provide Red Listing for the Tropical Important Plant Areas Bolivia project (TIPAs Bolivia) that has been running at RBG, Kew. It is quite clear that none of the six, together with other collections (see Specimens Examined), are P. insignis. This is now considered a Brazilian endemic, originally found on the Serra da Chapada north of Cuiába, Mato Grosso State, Brazil, as well as scattered localities in Goiás State, all on metamorphosed sandstone rock outcrops. The new species is described below:

Taxonomic Treatment

Praxelis cleggiae D.J.N.Hind & S.L.Edwards, sp. nov. Type: Bolivia, Departamento de Santa Cruz, Provincia Ñuflo de Chavez: Concepción, 7 km de Concepción sobre el camino hacia Lomerío, 16°10'18"S, 62°01'10"W, 476 m, 5 April 2008, Wood et al. 24182. Holotype: K(000374531); isotype: USZ.

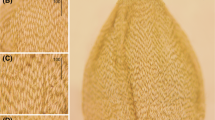

http://www.ipni.org/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:77340864-1

Short-lived, tap-rooted perennial herb to 50 cm tall, procumbent/decumbent and spreading to c. 2 m across/long (especially when growing in open areas across rock surfaces), or sometimes subshrubby, rootstock woody (especially when found growing in deep rock cracks). Stems terete, often reddish or purplish, longitudinally ridged, ridges sometimes yellowish-green, nodes often with conspicuous fascicles of young leaves on short-shoots in axils of lower leaves, internodes 2 – 9 cm (usually slightly shorter than leaf length or obviously longer), usually glabrous to sometimes sparsely hirsute (e.g. Soto & Escobar 922 and Wood 12533), hairs 1 – 2.5 mm long, uniseriate, septate, multicellular, eglandular, white. Leaves sessile or pseudopetiolate, opposite-decussate, lamina (1.5 –) 4.5 – 7.7 cm long × 0.2 – 0.6 cm wide, linear to linear-lanceolate, 3-veined from base, margins appearing entire to sparsely (and sometimes conspicuously) toothed, sometimes remotely so on more linear-lanceolate laminas, sometimes revolute, base and apex narrowly attenuate, primary veins on abaxial surface and margins sparsely hirsute, hairs 1 – 2 mm long, uniseriate, septate, multicellular, eglandular, white. Inflorescences of solitary capitula or 2 – 5-headed cymes or compound cymes; capitula pedicellate, pedicels 0.2 – 2.7 (– 8.7) cm long (measured to first bract) and apically dilated beneath involucre, bracteolate throughout, often with 2 or 3 bracteoles adnate to base of involucre, bracteoles 2 – 5, 3 – 4 mm long, triangular to filiform. Capitula homogamous and discoid, 6 – 10 mm tall × 6 – 11 mm diam. at apex; involucre campanulate; phyllaries 35 – 95, 4 – 5-seriate, all deciduous at achene maturity, outer 1.5 – 2.5 mm long × 1 – 1.5 mm wide, ovate, apex acuminate to acute, inner 6 – 7 mm long × 1 – 1.5 mm wide, linear, apex rounded to acute, 5 – 7-veined, margins ciliate to entire, cilia uniseriate, multicellular, eglandular, often unevenly spaced along margins, creamy green to purplish-pink (often much darker and rich Burgundy-coloured in herbarium material); receptacle 2 – 3.5 mm tall × 1.5 – 2.5 mm wide, convex to broadly cone-shaped, glabrous, entirely cream or cream at achene and involucre abscission zones, golden in between. Florets 70 – 150, hermaphrodite; corollas actinomorphic, 3 – 5 mm long × 0.3 – 0.7 mm diam., corolla tube cylindrical, tapering slightly towards base, silvery white or lilac, corolla lobes 5, 0.5 – 0.7 mm long, acute, densely papillose, papillae longer abaxially at corolla lobe apex, lilac; anthers 5, filaments adnate to corolla tube for ¼ to c. ½ their length, 1.5 – 2 mm long, anther collar balusterform, anthers 1.5 – 2 mm long × c. 0.25 mm wide, included in corolla throat, apical anther appendages ovate, 0.3 – 0.4 mm long × 0.14 – 0.2 mm wide, basal anther appendages rounded; style exserted, bulbous nectary at base of style, style base lacking basal node, style shaft 3 – 4 mm long, linear, glabrous, style arms 2 – 4 mm long, linear to narrowly clavate, apex rounded to obtuse, inner surface papillulose to division of style arms, outer surface papillulose to slightly above the division, lilac. Achenes 1.75 – 2.5 mm long, 0.6 – 0.7 mm wide, narrowly obovate and symmetrical, laterally obcompressed or concave and asymmetrical, black when mature, body sparsely setuliferous, setulae white, of adpressed twin-hairs, apical cells asymmetrical, acute, achene margins ±ciliate from dense, adpressed setulae, and appearing pale from narrowly-corky margins; carpopodium eccentric, triangular (adaxially) to elliptic (abaxially), cream, glabrous; pappus setae 17 – 24, 3.5 – 4 mm long, uniseriate (rarely appearing sub-biseriate, with scattered, considerably shorter setae with acute finely-barbellate apices, interspersed with normal setae), white, persistent. Figs 3A, B; 4; 5A, B.

Praxelis cleggiae. A rootstock; B prostrate stem portion with axillary clusters/tufts of leaves; C upper part of flowering stem; D apical part of flowering stem bearing one old capitulum, post-dehiscence of phyllaries and achenes, showing just the conical receptacle; E leaves; F capitulum; G l.s. capitulum; H middle phyllary apex — l.h. showing abaxial view, r.h. showing adaxial view; J innermost phyllary; K detail showing surface of receptacle; L floret; M detail of corolla lobe apex (l.h. view of adaxial surface, r.h. view of abaxial surface); N corolla opened out showing position of anther cylinder; P style and style arms; Q achene (obcompressed) in lateral view showing asymmetric carpopodium facing right (towards attachment point on receptacle); R base of achene showing adaxial surface and carpopodium; S detail of setula from achene body; T detail of apex of pappus seta. A, C, D, F – T from Wood et al. 24182 (holotype in K); B & E from Wood et al. 13202 (K). drawn by naoko yasue.

A Praxelis cleggiae at the edge of plant mat overlapping bare granite of whaleback inselberg surface, showing prostrate habit, tufted axillary leaves and rather divergent/divaricate habit — Between San Antonio de Lomerío and Concepción, Prov. Ñuflo de Chavez, Depto. de Santa Cruz, Bolivia; B Detail of an early-flowering capitulum of Praxelis cleggiae, showing conspicuous style arms and near ebracteolate pedicel. Between San Antonío de Lomerío and Concepción, Prov. Ñuflo de Chavez, Depto. de Santa Cruz, Bolivia. photos courtesy of the project ‘conservation of cerrados in eastern bolivia’.

recognition. Praxelis cleggiae is similar to P. insignis in that both species are procumbent and spreading, commonly have a single capitulum per inflorescence (if terminal) or inflorescence branch, and possess inconspicuously bracteolate pedicels. Praxelis cleggiae is distinguished from P. insignis in possessing markedly longer internodes (c. 2 – 9 cm vs c. 0.3 – 0.8 cm), with leaves scarcely longer than internode (vs leaves c. 3 – 6+ times longer than internodes); plants are branched throughout, often with fasciculate leafy short-shoots throughout plant, most secondary shoots typically divergent/ divaricate (vs plants usually only branched from base of the stem or just off from main stem and lacks axillary, fasciculate short-shoots; leaves are usually longer ([1.5 –] 4.5 – 7 cm vs 2.5 – 3.5 cm), and either linear (2 mm wide) or linear-lanceolate (– 6 mm wide) vs narrowly-lanceolate (3 – c. 4 mm wide) and narrowly attenuate (vs pseudopetiolate — Malme (1932: 28) described the pseudopetiole as a petiole, c. 5 mm long); involucres shorter (6 – 10 mm vs c. 10 mm) and inner phyllaries shorter (6 – 7 mm vs c. 9 mm), often with pink to Burgundy-coloured apices (vs green); pappus setae more numerous (17 – 24 vs 12 – 15), and shorter (3.5 – 4 mm vs c. 5 mm). Praxelis cleggiae is predominantly found on, or near to granitic inselbergs (and disjunct on the metamorphosed sandstones of the Serranía de San Simón, Beni, Bolivia), whereas P. insignis is found on sandstones (in Mato Grosso these are of the Furnas and Botucatu formations providing the relief of the Chapada dos Guimarães).

distribution. Known from granite inselbergs and immediate surrounding habitats (old road crowns and old road edges) in eastern Bolivia, in the Provinces of Chiquitos, Ñuflo de Chavez and Velasco, Departamento de Santa Cruz, and a disjunct locality on the Serranía de San Simón in the Provincia de Iténez, Departamento Beni.

specimens examined (and location of known duplicates). [Note: Numbers following herbarium acronyms are either accession numbers (e.g. for herbaria that have yet to digitise their collections), or herbarium barcodes.] bolivia. Departamento de Santa Cruz: Provincia Ñuflo de Chavez. Rancho Puesto Nuevo, 40 km S of Concepción, 16°25'S, 62°00'W, 700 m, 1 March 1987, Killeen 2348 (F, LPB, MO3031253, US01665339); Est. Salta, 10 km S of Concepción, 16°13'S, 62°00'W, 500 m, 14 April 1987, Killeen 2463 (F, LPB, US01665338, US01665450) [Note: This collection was cited as the voucher material for Praxelis insignis by Robinson (2014), and was in gravel soils of a ‘laterite outcrop’ — although, in this area, undoubtedly on granite!]; Sobre una loma en plena serranía San Lorenzo, 16°18'15"S, 62°33'02"W, 755 m, 10 March 2008, Soto & Escobar 922 (K000374532, USZ092398); c. 4 km S of Concepción on road to Lomerío, 500 m, 3 Aug. 1997, Wood 12533 (K000374533, K000374534, USZ); 12 km de San Javier en el camino a San Ramón, 16°21'25"S, 62°30'11"W, 445 m, 29 April 2012, Wood & Soto 27514 (K000374541, USZ); Lomerío, c. 45 – 50 km S of Concepción, 600 m, 1 March 1998, Wood et al. 13202 (K000374535, USZ56423); Concepción, 7 km de Concepción sobre el camino hacia Lomerío, 16°10'18"S, 62°01'10"W, 476 m, 5 April 2008, Wood et al. 24182 (holotype K000374531, isotype USZ); 23 km de San Antonio de Lomerío sobre el camino a Concepción, 16°35'58"S, 61°51'33"W, 415 m alt, 31 May 2008, Wood et al. 24982 (K000374538, USZ); San Xavier, 16 km de San Xavier hacia San Ramon, cerca de la hacienda Santo Rosario – El Jucio, 16.4011°S, 62.5192°W, 535 m, 15 March 2009, Wood et al. 25686 (K000374539, K000374540, USZ); c. 2 km S of El Cerrito, 16.35627°S, 61.52923°W, 436 m, 23 Feb. 2016, Wood et al. 27987 (K000374537, USZ); On and around granite ‘whaleback’ near La Panorama on old road to El Encanto, Concepción-Lomerío, 16.27607°S, 62.00041°W, 724 m, 6 March 2016, Wood et al. 28083 (K000374536, USZ). Provincia Velasco. Camino hacia las Mechitas, a 5 km del aseradero Cerro Pelão sobre el cerro, 14°32'35"S, 61°29'52"W, 500 m, 22 Jan. 1997, Guillén et al. 234 (MO1962815, US01665340, USZ03413) [Note: This collection was previously det. by Pruski, and by Robinson, as P. chiquitensis, and cited in Killeen & Schulenberg (1998: 241), although specifically noted as outside of the Parque; the Cerro Pelão is a granite inselberg, compared with the Meseta Huanachaca — the Huanchaca Plateau — which is largely composed of metamorphosed sandstone and provides a mosaic of vegetation]; Cerro Pelão, 14°31'54"S, 61°29'32"W, 450 m, 22 March 1994, Guillén et al. 1100 (MO1776975, US01665337, USZ01625) [Note: This collection was previously det. by Robinson as Chromolaena porophylloides (B.L.Rob.) R.M.King & H.Rob. (= Praxelis porophylloides (B.L.Rob.) D.J.N.Hind), a quite different species]; Parque Nacional Noel Kempff Mercado, 1 km S del desvio do los caminos hacia Pisofirme [sic!] y el aserradero Moira, 14°36'21"S, 61°29'33"W, c. 200 m, 3 July 1993, Saldias et al. 2942 (MO1776977, USZ59165) [Note: This is outside of the Parque’s limits, contrary to the label’s declaration.]. Departamento Beni. Provincia Iténez. Serranía San Simón ormaciones de pampa arbolada y algunas islas grandes de bosque alto; paisaje montañoso muy visible por la explotación de oro en la zona, 14°25'S [sic! — see Note], 62°03'W, 270 m, 19 July 1993, Quevedo et al. 980 (MO1776976 — originally det. as Chromolaena porophylloides, and later as P. chiquitensis (B.L.Rob.) R.M.King & H.Rob. by Pruski), US01665336 — det. by Robinson as Chromolaena porophylloides). [Note: This is the wrong latitude and longitude for the Serranía San Simón, Beni; it is usually given as 13°35'S, 62°08'W, and colloquially classed as one of the largest ‘mega deposits’ for gold outside of Potosí, although considered a ‘minor gold placer province of Bolivia’ (Biste et al. 1991).]

habitat and ecology. Praxelis cleggiae grows in rock cracks on granite inselbergs of all three types (lajas, whale-back or shield, or dome), as a component of the vegetation of the plant mats’ shallow soils on the inselberg surfaces, or in the surrounding cerrado vegetation on gravelly soils (especially compacted gravelly soils on the crown of rarely-used roads and tracks). Most habitats on rock are in, or have close proximity to, water, either as shallow temporary pools (e.g. Figs. 1B, 2B), or run-off from the surface of the rock (e.g. Figs 1B, 3A, B). Very rarely, plants grow in deep fissures in rocks, sometimes on exposed cliffs in, and rising above, the Chiquitania dry forest covering the summits, and with limited soil and no obvious water. Alt. 200 – 755 m.

conservation status. At present we prefer to consider the species as DD (Data Deficient) (IUCN 2022) until further detailed field work on several of the inselberg complexes can be carried out to formally provide a Conservation Assessment. Its relatively localised distribution within the Provincia of Ñuflo de Chavez and Provincia Velasco, and its disjunction to the Provincia Iténez, warrant closer study.

phenology. The species appears to flower and fruit sporadically between February and August, but this is clearly dependent upon the rains. Some collections made in February and March can see both abundant flowering, or only scattered flowering capitula on plants.

etymology. The species is named after Rosemary (Rosie) Clegg, formerly TIPAs Bolivia Co-ordinator, at RBG, Kew, now a post graduate student being co-supervised by the first author of this paper. Rosie first brought the issue of this species to the attention of the first author when she began assessing the species for Red Data listing, at which point a critical assessment was made of the material.

Discussion and Observations

Biste et al. (1991) used the term ‘inselberg massif’ to describe the Serranía San Simón, Dept. Beni, and described its vegetation cover as ‘dry savanna with sparse low semi-deciduous woodland ...’, and the bedrock as ‘low metamorphic clastic sediments of lower Proterozoic age.’; the Serranía is located in the San Ignacio Schist belt. The ‘gulches’ that run off the Serranía have ‘small sediment fillings’ which, at the base of the ‘massif’ join to form an ‘open valley’ with ‘thick base gravel beds’ (containing the gold).

The addition of Praxelis cleggiae to the Bolivian flora now raises the total number of species to seven (cf. Salgado et al. 2022). The presence of P. asperulacea (Baker) R.M.King & H.Rob. in Bolivia (based on Killeen & Wellens 6355, det. H. Robinson, cited in Killeen & Schulenberg 1998) was the result of misidentification of material supposedly of P. chiquitensis (B.L.Rob.) R.M.King & H.Rob. (see Robinson 2014: 357); it is highly probable that this material is another collection of P. cleggiae. It remains to be seen if P. diffusa (Rich.) Pruski is present in Bolivia. The total number of species now recognised in Praxelis is 20, since the present authors recognise P. grandiflora (DC.) Sch.Bip. as distinct from P. kleinioides (Kunth) Sch.Bip. (cf. Salgado et al. 2022: 307).

References

Abreu, V. H. R. de (2015). Palinologia e taxonomia de espécies de Praxelis Cass. (subtribo Praxelinae, Eupatorieae-Asteraceae) ocorrentes no Brasil. Unpubl. PhD Thesis, Centro Biomédico, Instituto de Biologia Roberto Alcântara Gomes, Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro.

____ (2020). Praxelis In: Flora do Brasil 2020. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. Available from: <http://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/reflora/floradobrasil/FB16265>. [Accessed 15 April 2021].

____ & Esteves, R. L. (2017). A new species of the Cerrado in Brazil. Phytotaxa 303 (1): 77 – 83. https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.303.1.7

____, da Conceição Santos, J., Esteves, R. L. & Gonçalves-Esteves, V. [2014] (2015). Pollen morphology of Praxelis (Asteraceae, Eupatorieae, Praxelinae) in Brazil. Pl. Syst. Evol. 301 (2): 559 – 608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00606-014-1098-5

Biste, M. H., Bufler, R. & Friedrich, G. (1991). Geology and exploration of gold placer deposits of the Precambrian Shield of Eastern Bolivia. In: G. Hérail & M. Fornari (eds), Gisements alluviaux d’or/ Alluvial Gold Placers/ Yacimientos aluviales de oro. La Paz: ORSTOM. Symposium International sur les Gisements Alluviaux d’Or, La Paz, 1991. pp. 145 – 158.

Christ, A. L. & Ritter, M. R. (2019). A taxonomic study of Praxelinae (Asteraceae – Eupatorieae) in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Phytotaxa 393 (2): 141 – 197. https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.393.2.5

Hind, D. J. N. (2011). An annotated preliminary checklist of the Compositae of Bolivia. Vers. 2. [See https://www.kew.org/science/tropamerica/boliviacompositae for the web version and https://www.kew.org/science/tropamerica/boliviacompositae/checklist.pdf for the PDF file of the checklist].

____ (2014a). Neocuatrecasia epapposa (Compositae: Eupatorieae: Gyptidinae), a new species from a shield inselberg in the Departamento de Santa Cruz, Eastern Bolivia. Kew Bull. 69 (3)-9526: 1 – 7. [https://doi.org/10.1007/S12225-014-9526-9].

____ (2014b). The identity of Eupatorium porophylloides, and a new combination in Praxelis (Compositae: Eupatorieae: Praxeliinae), from Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Kew Bull. 69 (4)-9549: 1 – 4. [https://doi.org/10.1007/S12225-014-9549-2].

____ & Frisby, S. (2014). Pectis harryi (Compositae: Heliantheae: Pectidinae), a new species from a rock platform in the Departamento de Santa Cruz, Eastern Bolivia. Kew Bull. 69 (3)-9250: 1 – 8. [https://doi.org/10.1007/S12225-014-9520-2].

____ & ____ (2015). The identity of Eupatorium bangii (Compositae: Eupatorieae: Praxeliinae) – and a new combination, Chromolaena phyllocephala, is finally made. Kew Bull. 70 (1)-9561: 1 – 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12225-015-9561-1

____ & Robinson, H. [2006] (2007). Tribe Eupatorieae. Compositae. In: Flowering plants. Eudicots: Asterales (J. W. Kadereit & C. Jeffrey (vol. eds)) of K. Kubitzki (series ed.), The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York. Vol. 8. pp. 510 – 574. [Note: This volume was distributed to authors and libraries in the middle of December 2006, with shipping notes as proof, even though the title page declared the publication date to be 2007.]

Ibisch, P. L., Rauer, G., Rudolph, D. & Barthlott, W. (1995). Floristic, biogeographical, and vegetational aspects of Pre-Cambrian rock outcrops (inselbergs) in eastern Bolivia. Flora 190 (4): 299 – 314. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0367-2530(17)30670-9

Itescu, Y. (2019). Are island-like systems biologically similar to islands. A review of the evidence. Ecography 42 (7): 1298 – 1314. [https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.03951]

IUCN [= IUCN Standards and Petitions Committee] (July 2022). Guidelines for Using the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria. Vers. 15.1. Prepared by the Standards and Petitions Committee. [Downloadable from http://www.iucnredlist.org/documents/RedListGuidelines.pdf ].

Jones, J. P. (1985). The southern border of the Guaporé Shield in western Brazil and Bolivia: An interpretation of its geologic evolution. Precambrian Res. 28 (2): 111 – 135. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-9268(85)90076-2

Keeley, S. C. & Robinson, H. (2009). Chapter 28. Vernonieae. In: V. A. Funk, A. Susanna, T. F. Stuessy & R. J. Bayer (eds), Systematics, evolution, and biogeography of Compositae. International Association for Plant Taxonomy, Institute of Botany, University of Vienna, Austria. pp. 439 – 469.

Killeen, T. J. & Schulenberg, T. S. (eds) (1998). A biological assessment of Parque Nacional Noel Kempff Mercado, Bolivia. RAP Working Papers 10, Conservation International, Washington, D.C.

King, R. M. & Robinson, H. (1987). The genera of the Eupatorieae (Asteraceae). Monogr. Syst. Bot. Missouri Bot. Gard. 22. Missouri Botanical Garden Press, St. Louis. pp.: I –[x], 1 – 581.

Loeuille, B., †Semir, J. & Pirani, J. R. (2019). A synopsis of Lychnophorinae (Asteraceae: Vernonieae). Phytotaxa 398 (1): 1 – 139. https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.398.1.1

Malme, G. O. A. (29 February 1932). Die Compositen der zweten Regnellschen Reise. II. Mato Grosso. Ark. Bot. 24A (Häfte 4, No. 8): 1 – 57.

Mamani, F., Pozo, P., Soto, D., Villarroel, D. & Wood, J. R. I. (ed.) (2010). Libro rojo de las plantas de los cerrados del Oriente Boliviana. Industrias Gráficas SIRENA, Santa Cruz.

Ribeiro, R. N., Rivera, V. L., Bringel Junior, J. B. de A., Salgado, V. G. & Proença, C. E. B. (2021). Re-evaluation of Praxelis (Asteraceae, Eupatorieae) in Brazil and description of Praxelis scaturicola, an unusual riverine species. Syst. Bot. 46 (4): 1131 – 1140. https://doi.org/10.1600/036364421X16370109698713

Robinson, H. (1999). Generic and subtribal classification of American Vernonieae. Smithsonian Contr. Bot. 89: [i –] iii, 1 – 116. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/184183#page/3/mode/1up

____ (2006a). New species and new combinations in Brasilian Eupatorieae (Asteraceae). Phytologia 88 (2): 136 – 153. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/48984#page/10/mode/1up

____ [2006b](2007). Subtribe Lychnophorinae. In: Flowering plants. Eudicots: Asterales (J. W. Kadereit & C. Jeffrey (vol. eds)) of K. Kubitzki (series ed.), The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants. Vol. 8: 161 – 162. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, New York.

____ (2014). Praxelis. In: P. M. Jørgensen, M. H. Nee & S. G. Beck (eds), Catálogo de las plantas vasculares de Bolivia. Monogr. Syst. Bot. 127 (2 vols), Vol. 1, Missouri Botanic Garden Press, St. Louis. pp. 357 – 358. [Asteraceae/Compositae: 290 – 382.]

Salgado, V. G., Grossi, M. A., Ribeiro, R. N., Proença, C. E. B. & Gutiérrez, D. G. (2022). Understanding Praxelis (Asteraceae, Eupatorieae): an updated taxonomy with lectotypifications and morphological and distributional clarifications. Austral. Syst. Bot. 35 (4): 296 – 316. https://doi.org/10.1071/SB21027

Teles, A. M., Viana, P. L. & Esteves, R. L. (2016). Taxonomic novelties in Praxelis (Asteraceae, Eupatorieae): a new species and a new combination. Phytotaxa 278 (1): 48 – 54. https://doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.278.1.5

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Naoko Yasue for the black and white line drawing. The authors would also like to thank John R. I. Wood and the Darwin Initiative Project, ‘Conservation of Cerrados in Eastern Bolivia’, for freely providing photographs from the project, of which four have been selected for this paper, and the first author would like to thank John for continuing discussions on the distribution of several plants in Eastern Bolivia. The first author would also like to thank Charlotte Fourneau (a vacation student in July 2019) who assisted with a project trialling the mapping of inselbergs in the Departamento de Santa Cruz, Bolivia, using satellite imagery, in conjunction with Rosie Clegg. We would also like to convey our thanks to two anonymous reviewers for their useful comments on an earlier draft of the script. Unfortunately, since that review and this script’s acceptance for publication, Salgado et al. (2022) published their revision of Praxelis. The result has been a considerable shortening of our original script, which had included a synopsis of the genus with many of the then necessary lectotypifications included. Necessary observations will be included in a forthcoming script on additional new species of Praxelis that the authors are describing.

Funding

No funding, grants, or other support were received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest, financial or non-financial, to declare that are relevant to the content of this paper.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hind, D.J.N., Edwards, S.L. Praxelis cleggiae (Compositae: Eupatorieae: Praxeliinae), a new species from the granite inselbergs in the east of the Departamento de Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Kew Bull (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12225-024-10189-1

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12225-024-10189-1