Abstract

This study aims to test an integrated model that explains volunteers’ intention to continue volunteering in an uncertain and turbulent environment such as the one caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. We argue that volunteers’ intention to continue is influenced by enthusiasm and personal constraints. Specifically, we assert that enthusiasm is influenced by intrinsic motivation, teamwork climate, and role ambiguity. Further, we propose the antecedents of personal constraints to be role ambiguity and perceived support. We conducted an online survey of potential respondents who were purposively sampled as active volunteers during COVID-19 pandemic. A total of 202 responses were complete and utilized for data analysis using a structural equation model. We found that enthusiasm has a positive influence on intention, while personal constraints has negative influence on intention. Further, we found that intrinsic motivation and teamwork climate positively influences enthusiasm, but enthusiasm is negatively influenced by role ambiguity. Similarly, personal constraints were found to be positively influenced by role ambiguity but negatively influenced by perceived support. The results of this study contribute to the discussion regarding the mechanism that increases volunteers’ intention to continue volunteering. Enthusiasm was found to be one of the factors, and its antecedents were empirically tested. In addition, the dual influences of role ambiguity imply the existence of two different paths to increase volunteers’ intention, which contributes to a deeper understanding of the formation of intention to continue volunteering. These findings provide insights and strategies on how to manage and retain volunteers for government and NPOs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Volunteers play a crucial role in serving and providing support to the community, especially in overcoming various challenges when the government has limited resources (Hotchkiss et al., 2014; Snyder & Omoto, 1992). As an example, the COVID-19 pandemic, with its rapid increase in positive cases, put enormous pressure on various aspects of people’s everyday, including physical and mental health, economy, education, and the environment. As a result, fast and appropriate responses are important in this situation. Many countries, however, were not yet ready to provide adequate responses to the surge in COVID-19 transmission, let alone the consequences of this surge (Harland et al., 2021; Schismenos et al., 2020). Governments, with limited resources and capabilities, were struggling to control the increase in positive COVID-19 cases and the adverse impacts of the pandemic on almost all sectors.

Despite the struggle, governments actually can make a significant appeal to citizen to encourage them to take part in volunteering activities to support the government in dealing with the pandemic. Government are faced with their limited capacity to control the transmission of the virus which provides many opportunities for volunteering activities (Harland et al., 2021; Schismenos et al., 2020). For individual volunteers, joining a government program to tackle pandemic-related issues means an opportunity to obtain internal and external rewards (Kifle Mekonen & Adarkwah, 2021; Kramer et al., 2021; Nencini et al., 2016). The ability of the government to meet volunteers’ needs will affect volunteers’ intention to join (Cho et al., 2020; Lockstone-Binney et al., 2021) and to continue their volunteering activities. In conditions where dissatisfaction occurs due to unmet needs, volunteers may cease their involvement (Cuthill & Warburton, 2005) in the volunteering program.

Being one of the beneficiaries of the many volunteering programs (Brudney & Kellough, 2000), the government must provide assistance to ensure that volunteers are functioning as they should. The government should be able to create conditions in which voluntary associations thrive (Cuthill & Warburton, 2005) by providing skills, knowledge, and the benefit of experience to volunteers (Brudney & Yoon, 2021). Since volunteers are motivated by both internal factors (e.g. feelings of empathy, altruism, religious convictions, community norms and family obligations) and external factors (e.g. recognition by community members and authorities, ambitions to get job opportunities, material and financial rewards and acquiring knowledge and skills), supporting both factors are crucial if the government is to retain volunteers.

Although volunteers’ intention to continue has been widely discussed in the literature (e.g., (Cho et al., 2020; Ferreira et al., 2015; Traeger & Alfes, 2019; Willems et al., 2012), the discussion on how volunteers’ intention to continue volunteering under uncertain condition and intense stress and pressure, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic, are scarce. From the practical side, this study is very important due to the significant roles of volunteers in providing support to carry out government programs successfully (Brudney & Kellough, 2000; Brudney & Yoon, 2021). During the COVID-19 pandemic, volunteers were playing crucial role in educating society, in providing personal support, as well as in maintaining health protocols to prevent wider virus transmission (Lai & Wang, 2022; Lazarus et al., 2021). These benefits meant that deploying and retaining volunteers in highly uncertain conditions was the government’s biggest challenge. In addition, there were also the challenges and constraints that volunteers faced when interacting with communities because they were not working alone in an environment that was a social vacuum (Sander-Regier & Etowa, 2014; Wayne et al., 2017). It is thus very important to understand the mechanism that underpins the volunteers’ intention to continue volunteering so that appropriate support can be provided.

We draw from various theoretical lenses to form the basis of this study. We utilize self determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000) to explain how intrinsic motivation has a positive impact on enthusiasm, which subsequently influences intention to continue volunteering. We extend the social determination theory explanation of how intrinsic motivation can influence intention to continue volunteering through the mediation of enthusiasm, and not only through satisfaction and commitment as argued by previous investigations (Bidee et al., 2017; Nencini et al., 2016). We also highlight the influence of external factors, namely teamwork climate, role ambiguity, and perceived social support. Teamwork climate is investigated from the perspective of collaboration theory (Colbry et al., 2014). The results of this study contribute to the deeper understanding of how teamwork climate works interpersonally to achieve common goals. Role ambiguity is investigated through the lens of role theory (Biddle, 1986), where it is assumed that individuals will behave according to their roles. These roles can be assigned, but when the assigned role is unclear, it creates ambiguity that can hinder the flow of work (Coghlan, 2015; Yan et al., 2021). This study contributes by examining how role ambiguity affects intention to continue volunteering. Lastly, our study contributes to social support theory (Cohen & McKay, 1984; Cohen & Wills, 1985) by explaining how perceived social support influences individual intention to continue volunteering. When volunteers do not receive support from other parties such as family, the community, or occupation then they will feel that the volunteer work has become a burden and difficult to do. Further, as volunteers also have other roles in their families or in their occupations, lack of support can become constraints on them continuing their volunteering activties. Based on these arguments, we propose two research questions: (1) What are the factors considered by volunteers in determining their intention to continue volunteering? And (2) What are the relationships between factors influencing intention to continue volunteering?

This research has two aims. Firstly, we try to understand the factors that determined volunteers’ intention to continue volunteering during the COVID-19 by integrating the internal and external factors. Secondly, this research tries to develop an integrated model to predict volunteers’ intention to continue volunteering during highly uncertain and highly demanding situations. More specifically, this study attempts to provide empirical evidence showing that enthusiasm, which originates from intrinsic motivation, positively influences intention to continue volunteering. While previous studies have shown the importance of enthusiasm to performance (Geoghegan, 2012; Kunter et al., 2011), very few of those that are available investigate the antecedents of enthusiasm in the context of volunteering activities. These findings extend our understanding of self determination theory in explaining how intrinsic motivation indirectly relates to behavioral intention by inducing experienced enthusiasm, in which intrinsically motivated volunteers would experience a relatively higher level of enthusiasm which subsequently influences intention to continue volunteering. Government and NPOs could benefit from this study in terms of managing and retaining volunteers which would contribute to the overall cost efficiency of programs. Knowing that enthusiasm is having a positive influence on intention to continue volunteering would encourage program coordinators to stimulate individuals’ intrinsic motivation by reminding them of the main reasons for joining such programs. Further, government and NPOs could intervene in the workplace by providing a clearer job description, stimulating a productive teamwork climate, and providing further support to leverage volunteers’ comfort in accomplishing their goals.

2 Conceptual background and hypotheses development

We utilize social determination theory, collaboration theory, role theory, and social support theory as the foundation of this study. We use social determination theory to investigate more deeply the influence of intrinsic motivation on intention. As an important driver of volunteering activites (Omoto & Snyder, 2002; Snyder & Omoto, 1992), it is imperative to understand how this type of motivation drives enthusiasm which subsequently influences an individual’s intention. The notion of enthusiasm is drawn from the field of education where it is an important factors that drives teachers’ performance and whether they continue to teach students (Burić, 2019; Kunter et al., 2011). We brought enthusiasm into volunteering context to see whether it would have a strong positive influence on volunteers’ intention to continue their activities, especially because volunteering is an additional role (Jensen & Agger, 2021; Kang, 2016) that is carried out by individuals for other different reasons. When conducting their activities, however, volunteers are embedded in a system that dictates their behavior. Volunteers face the dynamic of the workplace where many factors contribute to the burdens and challenges that individuals face in finishing their tasks. These burdens and challenges are often perceived by individual volunteers as constraints and hence they hinder the progress of their work. In the worst cases, volunteers will consider these constraints as factors that make them give up their work (Nencini et al., 2016; Willems et al., 2012).

Collaboration theory (Colbry et al., 2014) is the second theoretical perspective utilized in this study. Collaboration theory states that individuals work together irrespective of the structure and authority in their context. More specifically, Colbry et al. (2014) state that members of a team influence each other at the individual and team level because of turn-taking, cohesion, and the organization of work. Turn-taking indicates that an individual acknowledges others and alternately takes on different responsibilities. Cohesion and organization of work show how individuals in a team collectively think and behave so as to achieve a productive ecosystem to work and achieve goals. Individuals then feel excitement and pleasure when their working group is able to provide such an environment of open communication and good cooperation. When this happens, individual intention to continue volunteering will increase.

The third theoretical lens in this study is role theory (Biddle, 1986). The basic tenet for this theory is that individuals behave in a predictable yet different manner according to the social identities and the situations they face. Volunteers behave differently when they are in their working groups compared to when they are in front of their beneficiaries because they understand what the other parties expect from them (Anglin et al., 2022). When such role is vague, however, individuals have difficulties choosing which behavior to engage in front of others. This situation causes hindrance to goal attainment. When the vagueness dissipates, however, the hindrance will also disapear and individuals can work to attain their goals smoothly.

Lastly, we use social support theory (Cohen & McKay, 1984) to contribute on the mechanism of how family, companies, and the community provide support for individual volunteer. According to Cohen and McKay (1984), social support can act as buffer that protects individuals from strain and stress. The support itself can came from many sources, whether tangible or intangible (Lakey & Cohen, 2000). Since support can serve as buffer, it can reduce the burden individuals feel when faced with an intense and turbulent working environment. As a result, individuals will feel less constraints hence increasing their intention to continue their volunteering activities. Based on these four theoretical lenses, we explain the relationships between the variables as follows.

2.1 Volunteers’ intention to continue volunteering activities

It has been shown that volunteers have strong motivation and resilience in carrying out their duties (Carvalho & Sampaio, 2017; Choudhury, 2010), hence various programs incorporating volunteers are often very successful (Harp et al., 2017). Governments and NPOs are examples of two entities that encourage the participation of volunteers in their programs, whether it is short or long-term. Because most of the programs are short-term, volunteers are likely to face a delay or interval between different volunteering activities due to placement processes (Otoo, 2014). As a result, many volunteers experience a disruption of their spirit that reduces their level of enthusiasm which subsequently affects the intention to engage in their next volunteering activity. With these facts in mind, serious efforts are needed to manage and retain volunteers so that they are willing to continue their volunteering activities (Alfes et al., 2016; Studer, 2015).

Previous research suggests various internal and external factors to affect the continuing engagement of individuals in their volunteering activities (Cho et al., 2020; Ferreira et al., 2015; Henderson & Sowa, 2018; Nencini et al., 2016; Willems et al., 2012). Internal factors are factors that emerge from an individuals’ situation and can be in the form of their motivation, their economic conditions, age, health status, availability of time, and expertise. Some of these internal factors can naturally encourage individuals to continue their volunteering activities, such as motivation (Ferreira et al., 2015), while others might inhibit the continuation, such as a health or economic condition (Southby et al., 2019; Sundeen et al., 2007). External factors refers to factors from outside of the individual and can be in the form of support from the organization, superiors, the community, and family (Usadolo & Usadolo, 2019). In addition, volunteers usually work in teams so the work climate and team cohesiveness can be the determining factors that affect the continuation of volunteering activities (Nencini et al., 2016).

Other research emphasizes the experience of previous volunteering activities as an influence on an individual’s intention to continue being a volunteer. Cho et al. (2020) state that job satisfaction and volunteer management may drive individuals to continue volunteering. Similarly, Henderson and Sowa (2018) also find that job satisfaction and organizational commitment are determinants of volunteer retention. Further, Bennett and Barkensjo (2005) propose that the influence of negative experience, internal marketing, and job characteristics are important factors for individuals to decide whether they will continue their volunteering activities or not. Also important is an individual’s consideration of their relationship with clients and colleagues during the previous volunteering activities (Kewes & Munsch, 2019).

2.2 Volunteers’ enthusiasm and intention to continue volunteering

Enthusiasm is an important factor in determining a person’s attitude and behavior towards a task or job in many contexts. Research on the effect of enthusiasm on performance has been carried out in the field of education and it explains the effect of teacher enthusiasm on academic performance or student learning outcomes (Burić, 2019). In the field of sports, public enthusiasm for sporting events is found to influence the purchase of the products of the sponsors of sporting events (Hazari, 2018). In the field of health services, the effect of enthusiasm is evidenced by the willingness of family caregivers to continue to provide health services for dementia patients (Pierce et al., 2001). In the area of employee training, trainer enthusiasm is found to relate to the effectiveness of the training of salespersons (Arndt & Wang, 2014; Keller et al., 2016). Many literatures on teacher enthusiasm defines enthusiasm as a behavior that is exhibited (displayed enthusiasm) and as something that is experienced (experienced enthusiasm). Specifically, enthusiasm as an experience is related to feelings of excitement and enjoyment (Greenson, 1962). In the context of teaching, teacher enthusiasm has a positive effect on teaching that fosters creativity (Huang et al., 2021).

Individuals who are enthusiastic usually feel good and eager to share that good feel to others, as well as being well-oriented (Greenson, 1962). In this sense, Greenson (1962) also state that enthusiasm may change individual personality, meaning it could alter the values, cognition, attitudes, or even behaviors. As a result, enthusiasm is important in volunteering because it has the ability to move people and encourage the change that is needed (Geoghegan, 2012). When enthused, volunteers will happily share whatever they want to share with others. With this attitude, since the positive emotions create a sense of doing the right thing (Craggs et al., 2016), individuals will want to feel the same way, and thus enhance the intention to keep on doing the right things. Based on the previous related studies regarding the consequences of enthusiasm, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

-

H1: Volunteers’ experienced enthusiasm is positively related to volunteers’ intention to continue volunteering.

2.3 Volunteers’ personal constraints and intention to continue volunteering

In conducting their activities, volunteers may be seen as actors with resources and thus constrained in their utilization. There are not many studies specifically discussing the constraints faced by volunteers (Gage & Thapa, 2012) during the pandemic but there has been ample research conducted to investigate the constraints on volunteers on different contexts, such as in deprived areas (Davies, 2018) or in voluntourism (Otoo, 2014). Previous research has mentioned time as one of the barriers for individuals to engage in volunteering activities (Sundeen et al., 2007). Time barriers include the limited time individuals must devote to volunteering activities because it is not their first priority. Secondly, geographical factors are also a potential constraint on volunteering activities; some places are easy to reach while some other places restrict spatial mobility (Davies, 2018) causing individuals to rethink their volunteering activity. Other research has mentioned types of occupation as barriers to volunteering (Webb & Abzug, 2008) where people with managerial or professional jobs are those who are more willing to do volunteering work.

Age is also seen as a barrier that affects volunteering choices, where younger volunteers are seen as more resilient (Davies, 2018). Some volunteering activities require certain level of physical strength and thus individuals with poor health will refrain from continuing volunteering activity (Wymer et al., 1997). Lastly, individual economic circumstances are also assumed to be a barrier to individuals to continue their volunteering activity (Gage & Thapa, 2012). For those with lower economic status, an external reward would extend their willingness to get involved in volunteering activities. Based on the previous studies on the consequences of the constraints on volunteers, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H2: Volunteers’ personal constraints are negatively related to volunteers’ intention to continue volunteering.

2.4 Volunteers’ role ambiguity, personal constraints, and experienced enthusiasm

Role ambiguity is the degree to which clear information is lacking with regard to expectations associated with a role, methods for fulfilling known role expectations, and/or the consequences of role performance (Kahn et al., 1964). In new situations or under changing conditions, there may not even be implicit roles because no one in the group is sure of what the appropriate roles are in certain group situations. Even when roles are explicit, barriers to effective communication may make the message about the role unclear to the receiver. When a role is unclear or incomplete, the result is role ambiguity, or uncertainty about the content of an expected role. Taormina and Gao (2008) find that a sense of certainty regarding how a work should be executed is positively associated with work enthusiasm. From a different perspective, it can be stated that work uncertainty or ambiguity will be negatively associated with work enthusiasm. Further, role ambiguity has been found to hinder work engagement (Yan et al., 2021) and volunteers’ engagement (Harp et al., 2017). When there is uncertainty about what the task at hand is, individuals will feel they cannot make enough of a contribution in their volunteering activities (Coghlan, 2015) and this can reduce the level of enthusiasm.

In addition, role ambiguity may cause the inability of volunteers to align their volunteering activities with their constraints (i.e. current occupation and age). As an example, an unclear task will result in a longer amount of time needed to finish the volunteering activity, so the volunteer has to sacrifice his or her time for some other purpose, such as family or working time. As volunteering is usually not the individuals’ main priority, role ambiguity may escalate their perceived constraints. Further, uncertainty regarding the task can cause individuals to have a sense of futility (Wright & Millesen, 2008) that can hinder them from making further efforts. As a result, role ambiguity can enhance individuals’ perception of constraints in carrying out their volunteering work. Based on the previous studies on the consequences of role ambiguity, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

-

H3: Volunteers’ role ambiguity is negatively related to volunteers’ experienced enthusiasm.

-

H4: Volunteers’ role ambiguity is positively related to volunteers’ personal constraints.

2.5 Volunteers’ intrinsic motivation and experienced enthusiasm

Motivation is considered to be an important aspect that contributes to volunteering and, although altruism is said to be the most prominent motive for engaging in volunteering activity (Kifle Mekonen & Adarkwah, 2021; Silverberg et al., 1999), other researchers have found the importance of “serving others” as a motive (Wilson & Musick, 1997). Further, others have concluded that the biggest drivers of individuals to volunteer originate from individual values and understanding of others’ needs that are reflected in the activity of helping others and in expanding individual perspectives on certain issues (Gage & Thapa, 2012; Kifle Mekonen & Adarkwah, 2021). It is very often the case that volunteers do not act in a solitary activity but, instead, in a collective way by joining certain communities which subsequently has the implication that they are the recipients of external rewards (Gage & Thapa, 2012). Such external rewards, however, appear only after certain processes and thus intrinsic motives are also relevant in determining volunteering activity. Findings from a study by Lee and Lin (2014) fail to confirm the influence of salary satisfaction on job enthusiasm. They argue that the nonsignificant correlation between salary satisfaction and job enthusiasm is probably because the salary does not sufficiently motivate employees. The influence of salary satisfaction on job enthusiasm, however, is mediated by psychological contracts. These findings provide evidence that intrinsic motivation has a greater positive effect on individual enthusiasm.

An important faith-based motivation is discussed by Denning (2021) based on her participatory and ethnographic research. She explains the relationship between faith-based motivation, effort, and the enthusiasm of volunteers engaged in a project which responded to children’s holiday hunger. When individuals are motivated by religious faith to volunteer, they think their volunteering activities as something that may cause change that brings about a better future (Denning, 2021). Similarly, individuals may be motivated by the need to protect their country and reflect their patriotism. As a result, volunteers work more enthusiastically and this leads to persistence in volunteering. In addition, volunteers might be motivated to fulfil their needs (Butt et al., 2017; Gage & Thapa, 2012), such as self-actualization for enhancement. The thought of self enhancement could increase volunteers’ enthusiasm when conducting their activities. Volunteers could also feel that the government has not done enough to protect their community, so help from volunteers is needed (Butt et al., 2017). Understanding their contribution in this way, volunteers will work more enthusiastically. Based on the previous related studies on the consequences of motivation, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

-

H5: Volunteers’ intrinsic motivation is positively related to volunteers’ experienced enthusiasm.

2.6 Teamwork climate and volunteers’ experienced enthusiasm

Teamwork climate can be described as a prevailing teamwork atmosphere experienced by a team’s members. It is what it feels like for the members to work in that team. Teamwork is a vital aspect and a basic structural component of an organization’s design. It contributes to a more efficient and improved organizational performance. In teamwork, members of a team use their individual knowledge, experience and skills through dynamic interaction with other team members to achieve the common goals of the organization (Berber et al., 2020). Teamwork can be described as the process through which team members collaborate to achieve task goals. Huang et al. (2021), in their study in a teaching context, identified environmental factors, namely colleague innovation, teaching collaboration, participation in decision making, and availability of information and communication technology and equipment, as antecedents of teacher enthusiasm; furthermore, the consequences of teacher enthusiasm is teaching that fosters creativity.

In the context of volunteering activities, volunteers mostly work in teams. A positive teamwork climate encourages and sustains the motivation of a team’s members. Furthermore, co-worker support will positively affect work enthusiasm (Taormina & Gao, 2008). A good relationship with other volunteers will enhance enthusiasm because individuals want to feel the enjoyment of engaging volunteering activities together (Kewes & Munsch, 2019; Sander-Regier & Etowa, 2014). Teams with good internal relationships usually reflect a sense of cohesion between the individual team members (Hipp & Perrin, 2006) which supports an attachment to the group. As a result, the engagement in volunteering activities is increased. Based on the previous studies on the consequences of teamwork climate, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

-

H6: Teamwork climate is positively related to volunteers’ experienced enthusiasm.

2.7 Perceived supports and volunteers’ personal constraints

Managing volunteers involves recruiting, orienting, retaining, and organizing volunteers to provide a public good. As such, organizational factors can affect volunteers collectively. Organizational factors can also support or restrict volunteer coordination. To successfully coordinate volunteers, an organization should carefully assess and align itself to the needs of volunteers, the organization and to the community at large (Studer & von Schnurbein, 2013). Further, Studer and von Schnurbein (2013) find that organizational factors consist of leader or supervisor commitment, volunteer empowerment, evaluation, feedback, and appreciation/recognition. Organizational support will positively affect volunteers’ intention to continue their volunteering activities while a positive community response to volunteering activities, recognition, and appreciation will have a positive effect on volunteers’ satisfaction and resilience. Organizational support will also increase the future prospects of employees.

As volunteers, individuals face several constraints that hinder their volunteering activities, such as time, personal finance, or geographical location (Otoo, 2014). Support from organizations, family, and community will make the volunteers more flexible in aligning their volunteering activities with other activities (Maran & Soro, 2010; Weeks & MacQuarrie, 2011). Such support will make volunteers feel less constrained to engage in their volunteering activities. Based on previous studies, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

-

H7: Perceived support to volunteers is negatively related to volunteers’ personal constraints.

Based on the seven hypotheses discussed, we formulated the research framework as depicted in Fig. 1.

3 Method

We conducted this study by involving volunteers in Indonesia. Having the fourth largest population in the world, with these citizens spread across thousands of islands, Indonesia faces huge gaps in terms of infrastructure and uneven capacity to provide support. As a result, Indonesia was having difficulty providing services to the community during the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite such challenges, the local government and the communities and local volunteers played a crucial role in responding to emergency needs during the pandemic (Meckelburg, 2021). In some situations, the central and regional governments could not provide sufficient support in handling the pandemic which affected public confidence and trust in the government (Haryanto, 2021). Volunteer support, especially those with expertise in the health sector, was surely needed by the government in order to control the pandemic and serve the needs of the community (Lazarus et al., 2021).

This study has employed a mixed-method approach (Creswell, 2009; Venkatesh et al., 2013) with the qualitative part serving as an exploration of the various topics to be investigated while the quantitative part serving to test the model developed based on the qualitative study result. The mixed-method approach is appropriate for this study because it enables researchers to explore, to scrutinize, and to test various topics related to the phenomena under investigation. To obtain a realistic depiction of the context of volunteering during the pandemic in Indonesia, we conducted a preliminary data collection using individual interviews to understand the experiences of the volunteers based on their first person perspectives (Hudson & Ozanne, 1988). We conducted online, semi-structured individual interviews with thirty participants drawn from a government database based on certain criterion. Participants could be affiliated to certain organizations or be independent; they were still actively engaged in their volunteering activity; they resided in different cities around Indonesia, and they were working on different types of task (program planners, coordinators, implementors). We developed an interview transcript listing various topics that were considered relevant to explain volunteers’ perseverance based on our literature review. The list of question items is presented in Fig. 2. The data collection was conducted in September 2020 and lasted for approximately one month. The interview for each participant lasted between one and two hours. Data were transcribed and analysed individually utilizing content analysis before conducting cross-analysis to get an integrated view of the volunteers’ experience. Findings from the content analysis provided us with an important construct and enabled us to develop it into an integrated model as an input for the subsequent study.

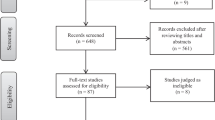

The second part of this study utilized a more positivist paradigm to test the integrated model developed in the first part of the study. In this part, we saw realities as having their own structures that are independent from the individuals’ perceptions (Hudson & Ozanne, 1988). We focused on testing the model developed from the preliminary interviews. We designed an online survey for potential respondents which were purposively sampled as active volunteers during COVID-19 pandemic. We distributed solicitation messages with the link to our survey in a government volunteer database that comprised volunteers across different regions in Indonesia. The participation in this survey is completely voluntary and anonymous. A complete list of the steps undertaken in this study are presented in Fig. 3.

Our principal investigation was into the seven variables that were our focus with scales developed from the findings from the preliminary study as well as from the available concepts pertaining to each variable. All of our variables were measured using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Our dependent variable was volunteers’ intention to continue volunteering. We utilized two items to measure an individual’s intention to leave and we assumed that an intention to leave was the opposite of an intention to continue volunteering (Usadolo & Usadolo, 2019). The two items were reflecting intention to leave, and we reverse-coded respondents’ opinions to ascertain the opposite meaning.

Experienced enthusiasm was measured by how volunteers felt the enjoyment and enthusiasm when engaged in their volunteering activities. Two items were utilized to measure enthusiasm based on the conceptualization and findings from the preliminary study (namely, “I do my tasks as a volunteer with great enthusiasm” and “I enjoy my tasks as a volunteer”). Personal constraints were measured by volunteers’ perception of the structural barriers they faced in participating in volunteering activities. We utilized three items focusing on constraints, which were age, economy, and work that hinders volunteers’ activities.

Intrinsic motivation was measured in terms of the volunteers’ internal drivers that encourage them to participate in volunteering actions. We utilized four items related to altruism, obligation, and religious conviction (Clary et al., 1998; Clary & Snyder, 1999; Gage & Thapa, 2012; Nencini et al., 2016) with items such as “I am called to help with protecting society”. Teamwork climate was measured as the atmosphere of cooperation experienced by each individual. We developed three items based on these conceptualization and findings from our preliminary study (such as “team members work cohesively”). The measurement items focused on the individual evaluation of the relationships with other volunteers when working together. Role ambiguity refers to the obscurity of an individual’s role and ways to perform such a role effectively. We developed three items based on these conceptualization and preliminary findings. An example of the items is “I don’t understand the planning and organization of my activities.” Our last independent variable was perceived support which we measured in terms of various kinds of support from entities that were close to the individuals that could encourage the continuation of volunteering activity. We utilized three items that focused on the support from family, the community, and the organization.

All of the measurement items underwent face validity checking by three experts who were also participating in the preliminary study. Once a consensus was reached with regard to terminology and the language utilized for every item, we developed the online questionnaire. We distributed the link to the questionnaire to the volunteers from the national database who were participating in the government’s volunteer program during the COVID-19 pandemic at the beginning of 2021 which lasted for around two months. We received a total of 213 responses, of which only 202 were complete and could be utilized for the data analysis. We utilized covariance-based structural equation modeling to test the relationship between the variables after ensuring the validity and reliability of the instruments.

4 Results

4.1 Qualitative study

4.1.1 Participants’ descriptives

Our participants (32 participants comprising 17 females and 15 males) were located across Indonesia and came from various types of organization that provided help during the COVID-19 pandemic. All of our participants were still active in their volunteering activites for which some were afforded dedicated time to be fully committed in the COVID-19 response program and some part of their time dedicated to volunteering. Detailed information regarding our participants are summarized in Table 1.

4.1.2 Results of content analysis

The results of the content analysis are summarized in Fig. 4. According to the iterative content analysis, we found that intrinsic motivation was an important driver for individual volunteers to continue their activities. Such findings correspond to those in a study by Omoto and Snyder (2002). Further, intrinsic motivation to volunteer was found to originate for different reasons. Volunteering is seen as a way to exercise religious obligation [P5, P9, P16, P29] or to defend the country during adversity [P2, P15, P23, P28]. Other prominent reasons that drive intrinsic motivation are the altruism nature as human being [P3, P17, P24] as well as for individual self actualization because they can join a big humanitarian entity [P8, P31, P32]. Meanwhile, intrinsic motivation can drive a positive attitude, and perceived support is also found to enable individual to feel positive. Support from family (e.g. in the forms of exemption from chores or being escorted to remote volunteering locations), from a company where the volunteers are permanently working (e.g., they have a flextime working arrangement), as well as from the community (e.g. which gives recognition or verbal support) were found to be factors that help volunteers persevere in undertaking such an extra role. Similarly, a good working climate with peers was found to increase volunteers’ excitement in carrying out their activities [P4, P10, P21, P30].

The results from the content analysis showed that volunteers were also faced many challenges and difficulties in accomplishing their tasks. It was found to be especially tough for volunteers when one aspect of job characteristics—namely role ambiguity—was a factor [P4, P15, P19, P26]. Role ambiguity is present when volunteers do not understand how an organization works, do not understand how to cater to the service beneficiaries, as well as not knowing how to seek support so that they can complete their job according to the assigned responsibilities. When faced with such ambiguity, individuals would feel their volunteering activities were a burden and very difficult to carry out. When the ambiguity was minimal, however, they would have a more positive attitude towards the task at hand. Our findings from the qualitative study provided us with initial factors (later used as the independent variables in the quantitative study) that might influence volunteers’ intention to continue their volunteering activities. Further, results from this stage of the study gave us valuable insights before designing and developing our questionnaire.

4.2 Quantitative study

4.2.1 Characteristics of respondents

Our respondents were mainly female (65.30%) in the age range of 17 to 37 years (Mage = 33.76, SD = 10.818) with a bachelor degree (56.40%) and married (54.50%). With such demographic characteristics, our respondents tended to represent the younger population (millennials) who were born between 1981 and 1996. In terms of occupation, our respondents were mostly employees, while 28.70% who were independent. For those who were currently working, they identified themselves as members of an organization (27.70%) or government employees (24.80%). Others identified themselves as professionals (11.90%). With regard to experience, most of our respondents stated that they had previous organizational (80.70%) and volunteering (61.40%) experience. Lastly, with regard to COVID-19 infection, 81.70% of the respondents stated that they had contracted the virus. Table 2 provides detailed information about the respondents’ demographic characteristics.

4.2.2 Measurement assessment

Prior to hypotheses testing, we performed a validity and reliability test. Principal factor analysis was utilized to test for convergent and discriminant validity. A load score above 0.6 and AVE score above 0.5 were deemed to be satisfactory (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2010) to check the convergent validity. Table 2 showed the items were loaded to their respective constructs with a factor load score above 0.6 and an AVE score above 0.5. To further check the discriminant validity, we compared the correlation score for each variable with the square root of the AVE value as summarized in Table 4. As shown, all square roots of AVE values were above the correlation coefficient between variables. These results provided evidence that it was a valid instrument. To test the internal consistency, we utilized a composite reliability score above 0.6 and Cronbach’s alpha score with score above 0.7 as a satisfying criteria (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). As seen in Table 3, all scores indicated satisfactory results, hence, the items utilized in this study were deemed reliable.

4.2.3 Hypotheses testing results

To test the hypotheses, we performed a covariance-based structural equation modeling test with the help of AMOS in IBM SPSS. The result for structural analysis indicated a good fit for the model: χ2(157) = 229.348, χ2/df = 1.461, p < 0.001, GFI = 0.902, IFI = 0.965, TLI = 0.957, CFI = 0.964, RMSEA = 0.048, and SRMR = 0.051. The R2 for intention to continue volunteering was 0.428, for experienced enthusiasm was 0.567, and for personal constraints was 0.315. These scores provide evidence that the model could provide considerable insight with regard to the antecedents of intention to continue volunteering, experienced enthusiasm, and personal constraints.

The result of the structural equation modeling (SEM) provide support for the seven hypotheses, as summarized in Table 4. Specifically, the result confirmed that experienced enthusiasm (B = 0.247, t-value = 3.047) and personal constraints (B = -0.534, t-value = 5.608) are the predictors of intention to continue volunteering. These results support H1 and H2. The results of the SEM also provide evidence of the influence of intrinsic motivation (B = 0.544, t-value = 7.437), teamwork climate (B = 0.243, t-value = 3.711), and role ambiguity (B = -0.254, t-value = 4.007) on experienced enthusiasm. The values support the confirmation of H5, H6, and H3. Lastly, the result of SEM analysis also provide strong support for H4 and H7; role ambiguity (B = 0.454, t-value = 5.745) and perceived support (B = -0.268, t-value = 3.503) are the predictors of personal constraint.

5 Discussions and conclusions

This study has found that experienced enthusiasm has a significant positive effect on volunteers’ intention to continue their activities, while the effect of personal constraints is negative. Specifically, the negative effect of personal constraints outweighs the positive effect of experienced enthusiasm. Several studies have shown that volunteerism is driven more by intrinsic than extrinsic motivation (Butt et al., 2017; Kifle Mekonen & Adarkwah, 2021; Silverberg et al., 1999). This study shows that the influence of intrinsic motivation on the continuation of volunteering activities is mediated by volunteers’ experienced enthusiasm. When volunteers contribute to the community with an intrinsic motivation, they tend to be more enthusiastic in accomplishing their goals because of the inherent joy and interest they derive from the nature of volunteering activity. There are enthusiastic volunteers, however, who might not be able to sustain their volunteering activities due to some constraints they cannot fully control. Detailed results of the hypotheses testing are presented in Table 5.

For example, when volunteers are feeling excited in doing their current volunteering and they start to think about continuing the same activities, their permanent occupation might hinder their evaluation of their own ability to accomplish the volunteering tasks optimally (Bennett & Barkensjo, 2005; Webb & Abzug, 2008). Similarly, volunteers with economic difficulties will also evaluate the future volunteering activities in terms of cost that must be covered during the activities (Gage & Thapa, 2012; Sundeen et al., 2007). Hence, maintaining volunteers’ enthusiasm is not powerful enough to ensure they continue carrying out the volunteering activities; there must be intervention in terms of personal constraints so that their negative effect on intention to continue volunteering can be reduced. This finding contributes to the deeper understanding of the antecedents of volunteers’ intention to continue volunteering by promoting the realization that there is a need to mitigate personal constraints. Such findings have been only rarely discussed in previous studies (e.g. (Gage & Thapa, 2012; Otoo, 2014; Southby et al., 2019; Sundeen et al., 2007).

Secondly, this study is one of only a small number of studies that discusses the antecedents of experienced enthusiasm, specifically among volunteers. While many previous studies have emphasized the importance of enthusiasm (e.g. (Craggs et al., 2016; Keller et al., 2016; Kunter et al., 2011), most of them have focused on elaborating the consequences of enthusiasm in general (e.g. Arndt & Wang, 2014; Keller et al., 2016). It is well-known that enthusiasm may boost performance (Arndt & Wang, 2014), but studies that present evidence, not propositions, on the antecedents of enthusiasm are scarce. Rooted in the actual experiences of the pandemic volunteers in Indonesia, this study is able to provide insights with regard to the antecedents of enthusiasm. We have found that intrinsic motivation and teamwork climate increases volunteers’ level of enthusiasm while role ambiguity tends to reduce the level of enthusiasm.

Intrinsic motivation has been found to provide a positive boost to volunteers’ enthusiasm due to its ability to fulfil individual volunteers’ needs to feel good or a “warm glow” (Andreoni, 1990). The proponents of the functional approach to motivation (Clary et al., 1998) state that different motivations will serve different kinds of goals. When there is the potential to attain goals and fulfil needs, individuals will feel enthusiastic during the activities (Zhang, 2013) and exert more effort to attain those goals (Wright & Millesen, 2008). Similarly, volunteers with supportive working conditions and good relationships with other members will tend to have a higher level of enthusiasm. Good relationships among members will enhance the sense of goal attainment (Berber et al., 2020) which will then increase enthusiasm (Hipp & Perrin, 2006; Taormina & Gao, 2008). In addition, the feelings of excitement about working with close friends in an activity can also contribute to the enhancement of enthusiasim among volunteers (Kewes & Munsch, 2019; Sander-Regier & Etowa, 2014).

Thirdly, this study confirms the dual influence of role ambiguity, namely reducing volunteers’ level of experienced enthusiasm and increasing the personal constraints. On one side, role ambiguity may cause confusion for individual volunteers due to unclear conceptualisation of the tasks in hand (Kahn et al., 1964). For enthusiastic volunteers, such obscurity will impair the supposedly smooth progress of their volunteering activities and thus may lessen the level of excitement felt during the process (Coghlan, 2015). In addition, role ambiguity may hinder volunteers’ engagement with their activities and other members due to the confusion it causes (Harp et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2021). Meanwhile, role ambiguity can also increase the personal constraints perceived by an individual volunteer. When faced with role ambiguity, individual volunteers will use their cognitive ability to evaluate whether they are able to deal with the ambiguity (Rogalsky et al., 2016). At times, when no clear standards are established by volunteer program coordinators, individual volunteers must creatively find ideas (Wang et al., 2011) to survive and to achieve the program’s goals. However, not all volunteers will have the ability to be creative when under harsh ambiguity (Wang et al., 2011) and thus they will feel restrained in continuing their volunteering activities. The dual influence of role ambiguity, when not subjected to intervention by a program coordinator, will burden the individual volunteers which will then negatively affect their intention to continue volunteering.

Taken together, the findings of this study highlight the importance of balancing factors that have positive or negative effects on volunteers’ intention to continue volunteering. While individual intrinsic motivation is crucial to encourage enthusiasm, which subsequently leads to the intention to continue volunteering, this study emphasizes the important role of the facilitating factors such as teamwork climate, role ambiguity, social support, and personal constraints. Since situational factors are found to affect intention to continue volunteering in many different ways, this study provides evidence on the different mechanism of such influence.

6 Theoretical contributions and practical implications

6.1 Theoretical contributions

This study draws on self-determination theory, collaboration theory, role theory, and social support theory to investigate how personal and environmental factors influence intention and behavior. The results of this study contribute by extending our understanding of these theories, specifically about the mechanism of each factor in driving volunteers intention to continue their activities. Firstly, we have found that enthusiasm is able to mediate intrinsic motivation into stronger intention to continue volunteering. This finding extends our understanding of how intrinsic motivation is able to evoke individual enthusiasm, which serves as an important factor to boost performance (Burić, 2019; Pierce et al., 2001). Secondly, we contribute to the literature on the collaboration theory by confirming how interpersonal interaction—in the form of teamwork climate—could contribute to enthusiasm due to the relational aspect embedded in collaborative culture. To our knowledge, this study is among the small number (e.g., (Forycka et al., 2022; Pierce et al., 2001) that have tried to investigate the influence of teamwork climate on an individual’s experienced enthusiasm which then subsequently increases the intention to continue volunteering.

Thirdly, we contribute to the literature on role theory by emphasizing the dual influence of role ambiguity. Role theory states that individuals will behave in accordance with a specific role in a specific situation (Anglin et al., 2022; Grube & Piliavin, 2000). The clarity of each role, then, becomes an important point that will lead individuals to perform their work seamlessly. When the role and the expectations of others are clear, individuals will be able to exhibit the appropriate attitude and hence feel reduced constraints to attain their goals. By contrast, when a role is ambiguous, the supposedly seamless work will be hindered and it will reduce the feeling of excitement and fun that an individual gets from doing the task at hand. Lastly, our findings contribute to the literature on social support theory and confirm that family, permanent working organizations, and the community could provide social support to individuals. Such support will enable them to feel that their volunteer work is the right thing to do because people in their surrounding environment recognize it and provide help. As a result, individuals will feel less burdens and constraints as they finish their tasks (Maran & Soro, 2010; Weeks & MacQuarrie, 2011).

6.2 Practical implications

From a managerial perspective, this study provides insights with respect to interventions needed to retain volunteers. While motivation is an individual-difference variable which is difficult to intervene, other variables (teamwork climate, role ambiguity, and social support) are under managerial control. Our study has found that teamwork climate could enhance volunteers’ enthusiasm which subsequently increase their intention to continue volunteering. The government and NPOs could build an additional program during training to bond all members of a volunteering program together (Keller et al., 2016). Bonding between members would benefit the team by giving them a sense of belonging and by feelings generated by attaining the same goals together (Sander-Regier & Etowa, 2014). Volunteering program organizers could also design a workflow that ensures open and intimate relationships between its members.

The tested model also provides a guideline for managers and organizations on how to accommodate the volunteerism of motivated and enthusiastic individuals by minimizing role ambiguity in order to increase enthusiasm and to reduce personal constraints. The need to have a clear guidance for tasks and a clear chain of responsibility for each volunteer are crucial to prevent vagueness (Studer & von Schnurbein, 2013). Formal and detailed job descriptions explaining the tasks in hand, the goals, the chain of responsibility, and the availability of support available to successfully complete the task might help individual volunteers to clarify their volunteering activities (Rogalsky et al., 2016). In addition, program coordinators must encourage effective communication—to and between members—as well as provide training for volunteers so they understand the general role-related information (Wright & Millesen, 2008). When possible, conducting a coaching session to simulate the actual tasks would benefit volunteers they receive evaluation and feedback.

Lastly, this study has also found that social support can reduce the personal constraints perceived by volunteers. The social support might be received from volunteers’ families, companies where they work, or the community in which they live (Usadolo & Usadolo, 2019). Since many of the volunteers nowadays are individuals who initially have a permanent job, they have rather limited time to accomplish the tasks in their volunteering activities (Piatak, 2016). Program coordinators might provide flexi-time options to accommodate volunteers with limited, inflexible schedules due to their occupation (Ackermann, 2019; Qvist, 2021). Having been implemented in the company context, flexi-time options may support individual independence to finish their tasks optimally within a specific time frame.

7 Limitations and future research

We acknowledge that this study has its limitations. This research was conducted with people who were actively participating in volunteering activities during the COVID-19 pandemic, hence they experienced a highly turbulent and uncertain environment. As a result, role ambiguity might be more prominent in this context than with other kinds of volunteering activities such as environmental volunteering or voluntourism. Future researchers might consider conducting studies in different conditions where there is role ambiguity (Wang et al., 2011; Wright & Millesen, 2008) to find out about its effects on volunteers’ performance and intention to stay.

Another limitation of this study is regarding the status of the respondents who were active volunteers. This study was not designed to include respondents who had already resigned from their volunteering activities. With only active respondents who were currently engaged in intense volunteering activities, the results of this study are not able to reflect the opinion of those who were actually resigning from the volunteering activities. An avenue for future research could be to include respondents who had already resigned from the volunteering activities (Willems et al., 2012) and compare the two groups (active and retired) to see whether there are differences in the underlying mechanisms.

Lastly, this research employs a cross-sectional study undertaken at one point in time. In addition, the sample is relatively small compared to the number of volunteers during the pandemic. Future research should strive to improve upon this method, such as by employing an experimental study (Alfes et al., 2016) to look more closely at the effects of the independent variables, specifically role ambiguity, support, and teamwork climate which are all relatively under managerial control. A longitudinal study (Lamb, 2019) could be employed to investigate the dynamics of intention to remain a volunteer at several points in time. Also, this study has focused on the Indonesian context and so future studies could expand into another countries to see whether differences exist in terms of the mechanism affecting individuals’ intention to remain as volunteers.

References

Ackermann, K. (2019). Predisposed to volunteer? Personality traits and different forms of volunteering. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly,48(6), 1119–1142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764019848484

Alfes, K., Antunes, B., & Shantz, A. D. (2016). The management of volunteers – what can human resources do? A review and research agenda. The International Journal of Human Resource Management,28(1), 62–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2016.1242508

Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. The Economic Journal,100(401), 464. https://doi.org/10.2307/2234133

Anglin, A. H., Kincaid, P. A., Short, J. C., & Allen, D. G. (2022). Role theory perspectives: Past, present, and future applications of role theories in management research. Journal of Management,48(6), 1469–1502. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063221081442

Arndt, A. D., & Wang, Z. (2014). How instructor enthusiasm influences the effectiveness of asynchronous internet-based sales training. Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education,22(2), 26.

Bennett, R., & Barkensjo, A. (2005). Internal marketing, negative experiences, and volunteers’commitment to providing high-quality services in a UK helping and caring charitable organization. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations,16(3), 251–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11266-005-7724-0

Berber, N., Slavić, A., & Aleksić, M. (2020). Relationship between perceived teamwork effectiveness and team performance in banking sector of Serbia. Sustainability,12(20), 8753. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208753

Biddle, B. J. (1986). Recent development in role theory. Source: Annual Review of Sociology,12, 67–92.

Bidee, J., Vantilborgh, T., Pepermans, R., Willems, J., Jegers, M., & Hofmans, J. (2017). Daily motivation of volunteers in healthcare organizations: relating team inclusion and intrinsic motivation using self-determination theory. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology,26(3), 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2016.1277206

Brudney, J. L., & Kellough, J. E. (2000). Volunteers in state government: Involvement, management, and benefits. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly,29(1), 111–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764000291007

Brudney, J. L., & Yoon, N. (2021). Don’t you want my help? Volunteer involvement and management in local government. The American Review of Public Administration, 027507402110023. https://doi.org/10.1177/02750740211002343

Burić, I. (2019). The role of emotional labor in explaining teachers’ enthusiasm and students’ outcomes: A multilevel mediational analysis. Learning and Individual Differences,70, 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.LINDIF.2019.01.002

Butt, M. U., Hou, Y., Soomro, K. A., & Acquadro Maran, D. (2017). The ABCE model of volunteer motivation. Journal of Social Service Research,43(5), 593–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2017.1355867

Carvalho, A., & Sampaio, M. (2017). Volunteer management beyond prescribed best practice: a case study of Portuguese non-profits. Personnel Review,46(2), 410–428. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-04-2014-0081/FULL/XML

Cho, H., Wong, Z., & Chiu, W. (2020). The effect of volunteer management on intention to continue volunteering: A mediating role of job satisfaction of volunteers. SAGE Open, 10(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020920588

Choudhury, E. (2010). Attracting and managing volunteers in local government. Journal of Management Development,29(6), 592–603. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711011046558

Clary, E. G., Ridge, R. D., Stukas, A. A., Snyder, M., Copeland, J., Haugen, J., & Miene, P. (1998). Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: A functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,74(6), 1516–1530. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1516

Clary, E. G., & Snyder, M. (1999). The motivations to volunteer: Theoretical and practical considerations. Current Directions in Psychological Science,8(5), 156–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00037

Coghlan, A. (2015). Prosocial behaviour in volunteer tourism. Annals of Tourism Research,55, 46–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ANNALS.2015.08.002

Cohen, S., & McKay, G. (1984). Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. In A. Baum, S. E. Taylor, & J. E. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of psychology and health (pp. 253-267). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin,98(2), 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Colbry, S, Hurwitz, M., & Adair, R. (2014). Collaboration theory. Journal of Leadership Education, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.12806/V13/I4/C8

Craggs, R., Geoghegan, H., & Neate, H. (2016). Managing enthusiasm: between “extremist” volunteers and “rational” professional practices in architectural conservation. Geoforum,74, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.05.004

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Editorial: Mapping the field of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research (Vol. 3, pp. 95–108). SAGE Publications, Sage CA. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689808330883

Cuthill, M., & Warburton, J. (2005). A conceptual framework for volunteer management in local government. Urban Policy and Research,23(1), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/0811114042000335269

Davies, J. (2018). “We’d get slagged and bullied”: Understanding barriers to volunteering among young people in deprived urban areas. Voluntary Sector Review,9(3), 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1332/204080518X15428929349286

Denning, S. (2021). Religious faith, effort and enthusiasm: motivations to volunteer in response to holiday hunger. Cultural Geographies,28(1), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474020933894

Ferreira, M. R., Proença, T., & Proença, J. F. (2015). Volunteering for a lifetime? Volunteers’ intention to stay in Portuguese Hospitals. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations,26(3), 890–912. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11266-014-9466-X/TABLES/6

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research,18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

Forycka, J., Pawłowicz-Szlarska, E., Burczyńska, A., Cegielska, N., Harendarz, K., & Nowicki, M. (2022). Polish medical students facing the pandemic—Assessment of resilience, well-being and burnout in the COVID-19 era. PLoS One,17(1), e0261652. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0261652

Gage, R. L., & Thapa, B. (2012). Volunteer motivations and constraints among college students. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly,41(3), 405–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764011406738

Geoghegan, H. (2012). Emotional geographies of enthusiasm: belonging to the Telecommunications Heritage Group. Area,45(1), 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1475-4762.2012.01128.X

Greenson, R. R. (1962). On enthusiasm. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association,10(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/000306516201000101

Grube, J. A., & Piliavin, J. A. (2000). Role identity, organizational experiences, and volunteer performance. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin,26(9), 1108–1119. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672002611007

Hair, J. F., Black, I. R., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective (7th ed.). Pearson Education.

Harland, C. M., Knight, L., Patrucco, A. S., Lynch, J., Telgen, J., Peters, E., Tátrai, T., & Ferk, P. (2021). Practitioners’ learning about healthcare supply chain management in the COVID-19 pandemic: a public procurement perspective. International Journal of Operations and Production Management,41(13), 178–189. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-05-2021-0348/FULL/PDF

Harp, E. R., Scherer, L. L., & Allen, J. A. (2017). Volunteer engagement and retention: Their relationship to community service self-efficacy. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly,46(2), 442–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764016651335

Haryanto. (2021). Public trust deficit and failed governance: The response to COVID-19 in Makassar, Indonesia. Contemporary Southeast Asia,43(1), 45–52.

Hazari, S. (2018). Investigating social media consumption, sports enthusiasm, and gender on sponsorship outcomes in the context of Rio Olympics. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship,19(4), 396–414. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-01-2017-0007/FULL/PDF

Henderson, A. C., & Sowa, J. E. (2018). Retaining critical human capital: Volunteer firefighters in the commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations,29(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11266-017-9831-7/TABLES/6

Hipp, J. R., & Perrin, A. (2006). Nested loyalties: Local networks’ effects on neighbourhood and community cohesion. Urban Studies,43(13), 2503–2524. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980600970706

Huang, X., Chin-Hsi, L., Mingyao, S., & Peng, X. (2021). What drives teaching for creativity? Dynamic componential modelling of the school environment, teacher enthusiasm, and metacognition. Teaching and Teacher Education, 107, 103491. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TATE.2021.103491

Hotchkiss, R. B., Unruh, L., & Fottler, M. D. (2014). The role, measurement, and impact of volunteerism in hospitals. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly,43(6), 1111–1128. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764014549057

Hudson, L. A., & Ozanne, J. L. (1988). Alternative ways of seeking knowledge in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research,14(4), 508. https://doi.org/10.1086/209132

Jensen, J. O., & Agger, A. (2021). Voluntarism in urban regeneration: Civic, charity or hybrid? Experiences from Danish area-based interventions. Voluntas, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11266-020-00297-4/TABLES/2

Kahn, R. L., Wolfe, D. M., Quinn, R. P., Snoek, D. J., & Rosenthal, R. A. (1964). Organizational stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity. Wiley.

Kang, M. (2016). Moderating effects of identification on volunteer engagement: An exploratory study of a faith-based charity organization. Journal of Communication Management,20(2), 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-08-2014-0051/FULL/PDF

Keller, M. M., Hoy, A. W., Goetz, T., & Frenzel, A. C. (2016). Teacher enthusiasm: Reviewing and redefining a complex construct. Educational Psychology Review,28(4), 743–769. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10648-015-9354-Y/TABLES/5

Kewes, A., & Munsch, C. (2019). Should I stay or should I go? Engaging and disengaging experiences in welfare-sector volunteering. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations,30(5), 1090–1103. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11266-019-00122-7

Kifle Mekonen, Y., & Adarkwah, M. A. (2021). Volunteers in the COVID-19 pandemic era: Intrinsic, extrinsic, or altruistic motivation? Postgraduate international students in China. Journal of Social Service Research,48(2), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2021.1980482

Kramer, M. W., Austin, J. T., & Hansen, G. J. (2021). Toward a model of the influence of motivation and communication on volunteering: Expanding self-determination theory. Management Communication Quarterly, 35(4), 572–601. https://doi.org/10.1177/08933189211023993

Kunter, M., Frenzel, A., Nagy, G., Baumert, J., & Pekrun, R. (2011). Teacher enthusiasm: Dimensionality and context specificity. Contemporary Educational Psychology,36(4), 289–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CEDPSYCH.2011.07.001

Lai, T., & Wang, W. (2022). Attribution of community emergency volunteer behaviour during the COVID-19 pandemic: A study of community residents in Shanghai, China. Voluntas, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11266-021-00448-1/FIGURES/1

Lakey, B., & Cohen, S. (2000). Social support theory and measurement. Social Support Measurement and Intervention, 29–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/MED:PSYCH/9780195126709.003.0002

Lamb, L. (2019). Changing preferences for environmental protection: evidence from volunteer behaviour. International Review of Applied Economics,33(3), 384–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2018.1510906

Lazarus, G., Findyartini, A., Putera, A. M., Gamalliel, N., Nugraha, D., Adli, I., Phowira, J., Azzahra, L., Ariffandi, B., & Widyahening, I. S. (2021). Willingness to volunteer and readiness to practice of undergraduate medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey in Indonesia. BMC Medical Education,21(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12909-021-02576-0/TABLES/3

Lee, H. W., & Lin, M. C. (2014). A study of salary satisfaction and job enthusiasm – mediating effects of psychological contract. Applied Financial Economics, 24(24), 1577–1583. https://doi.org/10.1080/09603107.2013.829197

Lockstone-Binney, L., Holmes, K., Meijs, L. C. P. M., Oppenheimer, M., Haski-Leventhal, D., & Taplin, R. (2021). Growing the volunteer pool: Identifying non-volunteers most likely to volunteer. Voluntas, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11266-021-00407-W/TABLES/5

Maran, D. A., & Soro, G. (2010). The influence of organizational culture in women participation and inclusion in voluntary organizations in Italy. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations,21(4), 481–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11266-010-9143-7/TABLES/1

Meckelburg, R. (2021). Indonesia’s COVID-19 emergency: Where the local is central. Contemporary Southeast Asia,43(1), 31–37.

Nencini, A., Romaioli, D., & Meneghini, A. M. (2016). Volunteer motivation and organizational climate: Factors that promote satisfaction and sustained volunteerism in NPOs. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations,27(2), 618–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11266-015-9593-Z/TABLES/6

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). The assessment of reliability. Psychometric Theory (pp. 248–292). McGraw-Hill.

Omoto, A. M., & Snyder, M. (2002). Considerations of community: The context and process of volunteerism. American Behavioral Scientist,45(5), 867. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764202045005007

Otoo, F. E. (2014). Constraints of international volunteering: A study of volunteer tourists to Ghana. Tourism Management Perspectives,12, 15–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2014.07.002

Piatak, J. S. (2016). Time is on my side: A framework to examine when unemployed individuals volunteer. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly,45(6), 1169–1190. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764016628295

Pierce, T., Lydon, J. E., & Yang, S. (2001). Enthusiasm and moral commitment: What sustains family caregivers of those with dementia. Basic and Applied Social Psychology,23(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324834BASP2301_3

Qvist, H. P. Y. (2021). Hours of paid work and volunteering: Evidence from danish panel data. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly,50(5), 983–1008. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764021991668

Rogalsky, K., Doherty, A., & Paradis, K. F. (2016). Understanding the sport event volunteer experience: An investigation of role ambiguity and its correlates. Journal of Sport Management,30(4), 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1123/JSM.2015-0214

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). When rewards compete with nature: The undermining of intrinsic motivation and Self-Regulation. In Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation The Search for Optimal Motivation and Performance (pp. 13–54). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012619070-0/50024-6

Sander-Regier, R., & Etowa, J. (2014). “I really like being with this group of people”: Social wellbeing and nature volunteering at Ottawa’s Fletcher Wildlife Garden. International Journal of Arts and Sciences,7(6), 291–304.

Schismenos, S., Smith, A. A., Stevens, G. J., & Emmanouloudis, D. (2020). Failure to lead on COVID-19: What went wrong with the United States? International Journal of Public Leadership,17(1), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPL-08-2020-0079

Silverberg, K., Ellis, G., Backman, K., & Backman, S. (1999). An identification and explication of a typology of public parks and rescreation volunteers. World Leisure & Recreation,41(2), 30–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10261133.1999.9674148

Snyder, M., & Omoto, A. M. (1992). Volunteerism and society’s response to the HIV epidemic. Current Directions in Psychological Science,1(4), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.EP10769014

Southby, K., South, J., & Bagnall, A. M. (2019). A rapid review of barriers to volunteering for potentially disadvantaged groups and implications for health inequalities. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations,30(5), 907–920. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11266-019-00119-2/TABLES/5

Studer, S. (2015). Volunteer management: Responding to the uniqueness of volunteers. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly,45(4), 688–714. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764015597786

Studer, S., & von Schnurbein, G. (2013). Organizational factors affecting volunteers: A literature review on volunteer coordination. Voluntas (24 vol., pp. 403–440). Springer Science and Business Media, LLC. 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9268-y

Sundeen, R. A., Raskoff, S. A., & Garcia, M. C. (2007). Differences in perceived barriers to volunteering to formal organizations: Lack of time versus lack of interest. Nonprofit Management and Leadership,17(3), 279–300. https://doi.org/10.1002/NML.150

Taormina, R. J., & Gao, J. H. (2008). A comparison of work enthusiasm and its antecedents across two Chinese Cultures. Journal of Asia Business Studies,2(2), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/15587890880000405/FULL/PDF

Traeger, C., & Alfes, K. (2019). High-performance human resource practices and volunteer engagement: The role of empowerment and organizational identification. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations,30(5), 1022–1035. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11266-019-00135-2/TABLES/4

Usadolo, S. E., & Usadolo, Q. E. (2019). The impact of lower level management on volunteers’ workplace outcomes in South African non-profit organisations: The mediating role of supportive supervisor communication. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations,30(1), 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11266-018-9970-5/TABLES/6

Venkatesh, V., Brown, S. A., & Bala, H. (2013). Bridging the qualitative-quantitative divide: Guidelines for conducting mixed methods research in information system. MIS Quarterly,37(1), 21–54.

Wang, S., Zhang, X., & Martocchio, J. (2011). Thinking outside of the box when the box is missing: Role ambiguity and its linkage to creativity. Creativity Research Journal,23(3), 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2011.595661

Wayne, S. J., Shore, L. M., & Liden, R. C. (2017). Perceived organizational support and leader-member exchange: A social exchange perspective. Academy of Management Journal,40(1), 82–111. https://doi.org/10.5465/257021

Webb, N. J., & Abzug, R. (2008). Do occupational group members vary in volunteering activity? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly,37(4), 689–708. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764008314809

Weeks, L. E., & MacQuarrie, C. (2011). Supporting the volunteer career of male hospice-palliative care volunteers. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine,28(5), 342–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909110389322

Willems, J., Huybrechts, G., Jegers, M., Vantilborgh, T., Bidee, J., & Pepermans, R. (2012). Volunteer decisions (not) to leave: Reasons to quit versus functional motives to stay. Human Relations,65(7), 883–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712442554

Wilson, J., & Musick, M. (1997). Who cares? Toward and integrated theory of volunteer work. American Sociological Review, 62(5), 694–713. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657355

Wright, B. E., & Millesen, J. L. (2008). Nonprofit board role ambiguity: Investigating its prevalence, antecedents, and consequences. The American Review of Public Administration,38(3), 322–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074007309151

Wymer, W., Riecken, G., & Yavas, U. (1997). Determinants of volunteerism: A cross-disciplinary review and research agenda. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing,4(4), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1300/J054v04n04_02