Abstract

Internationalization has been in the center of research interest in the past decades. With the increasing number of students studying abroad, there has been a growing need for higher education institutions to understand foreign student satisfaction and loyalty. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to distinguish between university- and non-university-related factors accountable for foreign student satisfaction, and to highlight the effect of non-university related factors on overall foreign student satisfaction and loyalty. A clear distinction made between foreign students based on the reason for their loyalty is also studied. The proposed theoretical model is examined with structural equation modeling (SEM) and with the method of partial least squares (PLS). Results show that both university-related and non-university-related satisfaction influence foreign student loyalty. Loyalty of foreign students could be distinguished between. Examined foreign students were proven to be loyal towards either the university, the study abroad experience or none of the above.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The internationalization of higher education has become the center of research interest in the past years (Buckner & Stein, 2020; Garwe & Thondhlana, 2021; Ghazarian, 2020). Even though there are certain contradictions – according to which higher education institutions (hereinafter HEIs) emphasize the importance of mobility and studying abroad, but at the same time they are eager to keep their students – the number of foreign students has been on the rise in recent years all over the world (Restaino et al., 2020; Van Mol et al., 2020). With the upsurge in international student numbers, there has been an increasingly renowned interest in investigating international students’ service quality expectations, satisfaction, and loyalty (Lovemore et al., 2020; Rehman et al., 2020), as satisfying students’ needs is of key importance at today’s higher education environment for retaining students and ensuring positive word-of-mouth recommendations (Alsheyadi & Albalushi, 2020; Landrum et al., 2021).

Some studies have been uncovered, which are concerned with foreign student country-, and institution-specific expectations and satisfaction (de Souza Câmara et al., 2020; Williams, 2020). In the majority of these research papers, examined factors are closely related to university service quality and include factors such as academic services, academic facilities, administrative services, HEI performance, and employee orientation (Alfy & Abukari, 2020; Moslehpour et al., 2020).

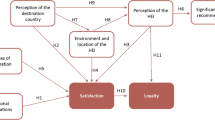

Non-university-related – potentially satisfaction and loyalty altering – factors beyond service quality are rarely studied or categorized (Alfano et al., 2021; Faizan et al., 2016; Mihanovic et al., 2016) but are not unprecedented. Amaro et al. (2019) revealed that the perception of the country, the environment and location of the HEI influence satisfaction, while the global perception of the HEI influences recommendations and increases student satisfaction and loyalty. As several factors beyond HEI service quality influencing student satisfaction and loyalty have been revealed, the topic seems crucial to investigate further for more successful strategic marketing decisions for HEIs to increase international student numbers (Amaro et al., 2019).

Loyalty of students has been a widely studied phenomena. It has mostly been examined from the service quality perspective (Alves & Raposo, 2009) and was found to be influenced by satisfaction (Alfano et al., 2021; Huybers et al., 2015). Pedro et al. (2020) found that loyalty of students included strong positive feelings, sense of belonging and pride of being part of the university. There has also been evidence that students are willing to give back to the university (Pedro et al., 2020). This suggests that student loyalty – and most importantly the meaning behind student loyalty – is a phenomenon to be further studied and investigated, so that student commitment – and thereby loyalty – can be enhanced.

Based on the above, the aim of this paper is to reveal what university- and non-university-related factors influence foreign student satisfaction and how satisfaction influences student loyalty. Furthermore, the study investigates if different types of student loyalty can be differentiated between, on which satisfaction might have an influence. Therefore, the paper intends to add to the higher education marketing literature by determining factors that may influence student satisfaction and contribute to loyalty, thereby further effecting student retention, positive word-of-mouth recommendations, student commitment, more effective student recruitment, and the creation of a successful marketing strategy.

In the paper, a research model is developed and analyzed with structural equation modeling (SEM), with the method of partial least squares (PLS) and with cluster analysis. These methods are widely used in previous higher education marketing literature for the measurement of expectations, satisfaction, and loyalty (Faizan et al., 2016; Savitha & Padmaja, 2017; Amaro et al., 2019).

2 Literature review, development of the theoretical model

The current paper investigates the connection between several notions. Therefore, the main theoretical aspects (expectations, satisfaction, and loyalty) used and examined throughout this paper are defined in the higher education marketing context specifically related to foreign students. Firstly, foreign students are determined as those students who come from foreign countries (except for neighboring countries) and have a foreign nationality. The definitions of expectations, satisfaction and loyalty are investigated and determined from the viewpoint of and are relevant to foreign students exclusively.

2.1 Key definitions

In order to examine the notions in-depth, first, an exact definition of expectations, satisfaction and loyalty is necessary in higher education marketing. In the higher education marketing literature, expectations are mostly studied together with satisfaction, and they are defined either as an influencing factor (Cardozo, 1965), as a basis for subjective comparison (Oliver, 1980), as a forecasting factor (Churchill & Surprenant, 1982), or as a result of previous experience (Woodruff et al., 1983). In the higher education marketing literature, they are mostly defined based on Oliver’s expectations disconfirmation theory (Chui et al., 2016; Oliver, 1980). Expectations regarding university-related and non-university-related factors both surface in the higher education marketing literature (Bryla, 2015; Byrne & Flood, 2005). In the current paper, international students’ expectations are defined as such recalled assumptions, which are about the whole study-abroad process, including both university- and non-university-related factors, relevant to the entire length of the study-abroad process.

Even though customer satisfaction is a notion extensively studied in the higher education marketing literature, there is no common understanding on its exact definition. It is mostly referred to as the result of the comparison between expectations and experience (Churchill & Surprenant, 1982; Oliver & Bearden, 1985; Elkhani & Bakri, 2012). The higher education marketing literature highlighted the fact that foreign student satisfaction is influenced by a variety of factors. However, these factors are not clearly differentiated between. There is a negligible number of studies focusing on non-university-related satisfaction (Alfano et al., 2021; Faizan et al., 2016; Mihanovic et al., 2016), while the majority of studies focus on university-related aspects of satisfaction (Giner & Rillo, 2016; Alfy & Abukari, 2020; Moslehpour et al., 2020). In the current paper, foreign student satisfaction has been determined as the comparison between expectations and experience, which is related to the whole study-abroad process of students and is relevant to both university- and non-university-related issues. Satisfaction can materialize during and after the consumption of the higher educational service. University-related satisfaction includes those factors which the university has direct effect on, while non-university-related satisfaction means factors on which the university does not have a direct effect.

Satisfied customers do not always transfer to loyal ones. Loyalty has initially been determined as an equal to satisfaction and retaining customers (Reichheld, 1996; Reichheld & Sasser, 1990), while others stated that loyalty can be measured by repurchase (Oliver, 1999; Reichheld et al., 2000). According to a more complex approach of loyalty, it includes not only repurchase, but emotional attachment, commitment, and possible word-of-mouth recommendations (Oliver, 1999; Reichheld, 2003). In the current study, loyalty is defined according to the latter approach, as – besides being a possible repurchase – positive attitude, commitment, and recommendation (positive WOM), which can materialize during and after the study-abroad process.

2.2 Development of the theoretical model

The revision of key terms provided a basis for the proposed theoretical model. Regarding expectations, the secondary research revealed specifically university-related expectations (Cheng, 2014) and non-university-related ones as well (Aldemir & Gülcan, 2004; Byrne & Flood, 2005). Therefore, expectations can be interpreted as a sum of these two factors. Furthermore, in the literature of higher education marketing, several research essays explore the link between these expectations and satisfaction, many of which compare student expectations and experience based on the SERVQUAL quality concept (Chui et al., 2016; Gregory, 2019), thus determining student satisfaction. In other studies, student satisfaction is researched based on consumer indices, in which expectations are present as a factor influencing satisfaction (Pezeshki et al., 2020; Zhai et al., 2017). In previous research there is evidence that student expectations have an effect on student loyalty (Alves & Raposo, 2009; Shahsavar & Sudzina, 2017). Therefore, in the current study, foreign student expectations are believed to have an influence on foreign student satisfaction. Based on this conclusion and the secondary literature on higher education marketing, the following hypotheses can be set:

-

H1: Foreign student expectations have an effect on university-related foreign student satisfaction.

-

H2: Foreign student expectations affect non-university-related foreign student satisfaction.

There have been numerous studies found in the higher education marketing literature related to both university- and non-university-related satisfaction (Alves & Raposo, 2009; Mekic & Mekic, 2016). Closely university-related satisfaction measurements mostly explore elements of service quality with dimensions defined based on previous research (Cardona & Bravo, 2012; El-Hilali et al., 2015; Lenton, 2015). However, there is no uniformity in the interpretation and grouping of factors influencing university-related student satisfaction. Therefore, based on the higher education marketing literature review, this study explores and synthetizes factors previously appearing in the literature.

Tangible elements of the higher education service environment have been proven to be crucial in student satisfaction (Chui et al., 2016; Lenton, 2015). Among others, Lenton (2015) has proven that tangibles influence student satisfaction and Elliot and Healy (2001) found that academic atmosphere plays an important role in student satisfaction. Tangible resources – studied with a model for measuring higher education performance – such as generally up-to-date study equipment, university campus environment, layout, infrastructure (Cardona & Bravo, 2012), and visually appealing facilities have been found to have a positive effect on student satisfaction (Ahmed & Masud, 2014). Based on this evidence the following hypothesis is set:

-

H3a: Tangibles have a positive effect on university-related foreign student satisfaction.

The influence of academic staff competences on student satisfaction appeared in previous higher education marketing literature (Long et al., 2014). Service excellence (Elliot & Healy, 2001), the education process and staff-student communication (Cardona & Bravo, 2012) reportedly affected student satisfaction. Moreover, competencies (Long et al., 2014), the knowledge of academic staff and their ability to answer student questions and the fact that they are highly educated influenced student satisfaction (Ahmed & Masud, 2014). Teaching methods and the effects of teaching were also proven to have an effect on student satisfaction (El-Hilali et al., 2015; Lanton, 2015; Santos et al., 2020). Based on this, the following hypothesis can be stated:

-

H3b: Competence of HEI professionals has an effect on university-related foreign student satisfaction.

In the higher education marketing literature, the content of the curriculum taught at universities was shown to affect student satisfaction. Service excellence (Elliot & Healy, 2001) and the higher education program (El-Hilali et al., 2015) both had effects on the satisfaction of students. Curran et al. (2010) found that an up-to-date curriculum design significantly influences student satisfaction. Furthermore, Ahmed and Masud (2014) found that the offer of highly reputable programs, flexible timetable and schedule can have a positive effect on student satisfaction. Based on this, the following hypothesis can be stated:

-

H3c: The content of curriculum has a positive effect on university-related foreign student satisfaction.

Besides tangibles, competences and the content of the curriculum, previous research has shown that attitude is a factor that can influence satisfaction. Elliot and Healy (2001) found that both university and individual support and focus on students influence student satisfaction. If academic staff show positive attitude towards students, have a positive relationship with students, understand student needs, and students receive feedback from teachers, higher student satisfaction could be perceived (Ahmed & Masud, 2014). This corresponds with Lenton’s (2015) findings stating that institutional support for students and attention to personal development influences student satisfaction. We can therefore state the following hypothesis:

-

H3d: The attitude of HEI colleagues (teachers and administrative staff) has a positive effect on university-related foreign student satisfaction.

Another factor that might influence foreign student satisfaction is the reliability of HEI colleagues. There is evidence in the higher education marketing literature that if students can rely on HEI staff and they can trust them, or if the academic stuff shows sincere interest in student problems and responds in a timely manner, these can contribute to student satisfaction (Ahmed & Masud, 2014). Most studies using the higher education service quality include reliability, resulting in its importance and effect on student satisfaction (Chui et al., 2016; Yousapronpaiboon, 2014). Therefore, the following hypothesis can be set:

-

H3e: Reliability of HEI colleagues (teachers and administrative staff) has a positive effect on university-related foreign student satisfaction.

The delivery of the curriculum has been proven to have an influence on student satisfaction in previous higher education marketing literature. Research revealed that teaching methods (El-Hilali et al., 2015), providing feedback and support for students (Lenton, 2015), communicating well in the classroom with students (Ahmed & Masud, 2014) can influence student satisfaction. Hence, the following hypothesis is set:

-

H3f: Delivery of curriculum has a positive effect on university-related foreign student satisfaction.

There are only a scarce number of studies that are concerned mainly or partly with uncovering the non-university-related satisfaction determinants of foreign students (Machado et al., 2011; Mihanovic et al., 2016; Smith, 2020; Yang et al., 2013). In these studies, even though they are called otherwise, factors are usually closely related to the university itself (Yang et al., 2013). Based on the review of higher education marketing literature, this study synthetizes non-university-related factors that might have an influence on student satisfaction.

Evidence from the higher education marketing literature shows that personal life and housing influences student satisfaction in a foreign country (Mihanovic et al., 2016). Living in a new city can be challenging for foreign students and it thereby affects satisfaction (Machado et al., 2011; Jiang et al., 2020). Living costs can also mean an additional burden to consider when studying abroad and can influence the satisfaction of students (Pezeshki et al., 2020). Besides living in a new city and having to deal with living costs, living conditions are also crucial and are proven to have an influence on student satisfaction (Smith, 2020). Based on this evidence from the literature, the following hypothesis is stated:

-

H4a: Living in the city has an effect on non-university-related foreign student satisfaction.

Closely related to living in the city of the chosen HEI, the international environment outside the university appears as an influencing factor of student satisfaction (Smith, 2020). The international environment further includes the possibilities for social life of students, being able to meet other foreign or local people and participate actively day by day in this international environment outside the university’s walls (Machado et al., 2011; Smith, 2020; Jiang et al., 2020). This also includes being part of an international environment on both personal and social levels (Mihanovic et al., 2016). Based on this, the following hypothesis is created:

-

H4b: The international environment outside the university has an effect on non-university-related foreign student satisfaction.

Foreign students living in a new city do not only explore the university and its halls, but during their study program, they also get access to different public facilities and leisure activities via their social lives (Mihanovic et al., 2016; Smith, 2020). Those facilities that are available for the local citizens are also there to be used by foreign students as well. Therefore, the importance of different cultural and sport facilities, public parks and access to leisure activities can play a crucial role in student satisfaction (Aldemir & Gülcan, 2004), so the following hypothesis is set:

-

H4c: Public facilities and access to leisure activities have an effect on non-university-related foreign student satisfaction.

Having public facilities is not enough for a city from the perspective of foreign students. These students need to have access to any other additional places where they can spend their free time and relax. Different social and free-time activities were found to be of key importance when it comes to student satisfaction (Mihanovic et al., 2016). Moreover, the opening hours of these facilities also influence satisfaction (Abdullah, 2006). Based on these, the following hypothesis is stated:

-

H4d: Access to places to spend free time at has an effect on non-university-related foreign student satisfaction.

Last, but not least, some students may not have the opportunity to have their studies financed fully by their families or by a scholarship. Others might feel that they would like to gain practical experience and have a career related to their studies while learning abroad (Letcher & Neves, 2010). Therefore, some may decide to start working besides their studies and expect to have job opportunities (Karemera et al., 2003). Previous studies have found that the possibility for foreign students to have a job in a foreign country can highly influence their satisfaction (Pezeshki et al., 2020).

-

H4e: Job opportunities have an effect on non-university-related foreign student satisfaction.

Researchers enlist several main factors influencing students’ loyalty, such as the availability of study programs, location, size, and complexity of the HEI, the quality of teaching (Huybers et al., 2015), feedback from and communication with teachers (Jager & Gbadamosi, 2013), a proper study pace, student supporting facilities, tangibles, and equipment (Wiers-Jenssen et al., 2002). Based on the evidence from these studies, satisfaction with closely university-related issues supposedly has an effect on the loyalty of foreign students.

-

H5: University-related foreign student satisfaction has a positive effect on foreign student loyalty.

Numerous higher education marketing studies have proven the relationship between the satisfaction and loyalty of foreign students (Alves & Raposo, 2007; Alves & Raposo, 2009; Elliot & Healy, 2001; Wiers-Jenssen et al., 2002; Lenton, 2015; Cardona & Bravo, 2012; Owlia & Aspinwall, 1996; El-Hilali, et al., 2015; Lee, 2010; Schertzer & Schertzer, 2004; Giner & Rillo, 2016). In previous research, WOM and its role in loyalty was found to be significant (Alves & Raposo, 2007; Alves & Raposo, 2009; Kakar et al., 2021). Despite the extensive literature on higher education marketing and international students’ satisfaction, only a small portion of these studies is concerned with those factors, which are not closely university-related, but might influence the satisfaction and loyalty of students (Alfano et al., 2021; Faizan et al., 2016; Mihanovic et al., 2016; Schertzer & Schertzer, 2004; Yang et al., 2013). Based on the evidence in the higher education marketing literature, the following hypothesis can be stated:

-

H6: Non-university-related foreign student satisfaction has a positive effect on foreign student loyalty.

Based on the previously examined higher education marketing literature and the hypotheses, the conceptual model of the quantitative research of the current study can be seen on Fig. 1.

3 Methodology and sample

The primary research method of the paper is an online questionnaire, which was available to fill between March and April 2019. Constructs were measured with Likert-scale questions, as their usage in higher education marketing studies is an internationally accepted methodology (Gronholdt et al., 2000; Turkyilmaz et al., 2018). Expectations scales were measured based on Østergaard and Kristensen (2005), while university-related and non-university-related satisfaction measurement relied on studies from Owlia and Aspinwall (1996), Mihanovic et al. (2016) and Machado et al. (2011). Foreign student loyalty was measured partly by scales used in previous studies (Østergaard and Kristensen, 2005; Alves & Raposo, 2009), and scales developed by the authors. These scales’ reliability was tested with Cronbach-alpha and were deemed suitable for further analysis.

The method used for analysis included PLS-SEM and cluster analysis. The examined theoretical concepts of expectations, satisfaction and loyalty were studied as latent variables. To examine the hypotheses, the relationship between the latent variables was investigated with structural equation modeling (SEM), as this methodology can be applied higher education marketing research (El-Hilali et al., 2015; Giner & Rillo, 2016; Kazár, 2014). In this study, the partial least squares (PLS) technique (Hair et al., 2014) can be applied, as the variables are not normally distributed (in case of both Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests and in case of each variable it is p < 0,01). SmartPLS 3 software was used for the PLS path analysis (Ringle et al., 2015). Additionally, to classify foreign students participating in the survey into separate sub-groups, cluster analysis was conducted, as it is a methodologically accepted way to classify university students into sub-groups in higher education marketing studies (Saenz et al., 2011; Caliskan et al., 2013; Gallyamova et al., 2018; Bennasar-Veny et al., 2020). The aim of the cluster analysis was to determine whether students could be classified based on their loyalty.

The sample of the study was drawn from international students studying full-time at the chosen university in Hungary. The University of Szeged was the subject of the current study, as it has been welcoming foreign students for more than 30 years. With a continuously growing number of study programs available for foreign students, this university presents a good opportunity for the current research, as results might be of key importance in the marketing directions the institution intends to take to attract and retain more foreign students. At the time of the research, about 2505 foreign students were studying at the university, while the sample consisted of 188 students. The sample size can be considered relatively small due to no direct contact to foreign students and their low willingness to fill in surveys. However, regardless of the sample size, the current study can provide us with a better understanding on their satisfaction and loyalty, based on which further research could be conducted on a bigger sample. Respondents’ country of origin was varied, they arrived at the destination from more than 40 countries and studied almost on every faculty of the examined university. Due to the nature of the survey, it cannot be deemed representative.

4 Results

The constructs’ validity was examined with Cronbach-Alfa and CR (composite reliability) indicators in the outer model. Results suggest that each examined construct reaches the minimum value (> 0.6 Hair et al., 2009). Convergence validity was examined with standardized factor weights and AVE (average variance extracted) indicators. Factor loadings above 0.6 and below 0.7 were also accepted (Hair et al., 1998; IRM, 2014), as AVE indicators exceeded the minimum value (> 0.5 Hair et al., 2014) in case of each latent variable, after two variables were excluded from the analysis. Therefore, the existence of all remaining constructs is validated. Discriminant validity was examined based on the test of Fornel and Larcker (1981) and the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) (Henseler et al., 2015). Each variable met the Fornel and Larcker criterion, as variables’ AVE values were higher than the squares of the correlation coefficients between the construct and the other constructs. The HTMT of each examined variable was smaller than one (Henseler et al., 2015). Therefore, discriminant validity is established. The outer model suggests the existence of the latent variables and each indicator represents the same phenomenon.

The bootstrap algorithm helped to test the path coefficients’ significance regarding the inner model (Hair et al., 2014). The number of iterations were 5000. The results show that 7 paths can be considered significant, while 8 paths are non-significant in the model (H1, H2, H3a, H3d, H3e, H3f, H4c, H4e). The latter ones mean that expectations do not have an effect on either university-, or non-university-related satisfaction (H1, H2); tangibles, attitude and delivery (H3a, H3d, H3e, H3f) do not affect university-related satisfaction; public facilities and job opportunities (H4c, H4e) do not influence non-university-related satisfaction.

After leaving out the non-significant effects from the model, the PLS algorithm was run again, and each remaining path has a significant effect at a five percent significance level. The significant paths can be seen in Table 1. In case of the outer model, running the PLS algorithm did not affect the criterion values (Cronbach-alpha, CR, AVE, standardized factor loadings, Fornell-Larcker criteria and the HTMT).

After the exclusion of non-significant paths, the final model can be seen on Fig. 2. There are positive paths observed in each case. Standardized path coefficients (β) show that:

-

the content of curriculum (β = 0.485) has a stronger effect on university-related foreign student satisfaction than competences (β = 0.312).

-

living in the city (β = 0.578) has the strongest effect on non-university-related foreign student satisfaction, followed by places to spend free time at (β = 0.275) and international environment (β = 0.127).

-

university-related foreign student satisfaction has a stronger effect (β = 0.720) on foreign student loyalty than non-university-related foreign student satisfaction (β = 0.135).

Results show that H3b, H3c, H4a, H4b, H4d, H5 and H6 can be accepted. Competences and content of curriculum (H3b, H3c) affect university-related foreign student satisfaction, while living in the city, international environment, and places to spend free time at (H4a, H4b, H4d) influence non-university-related foreign student satisfaction. Both satisfaction types have an effect on foreign student loyalty (H5, H6).

As factors influencing foreign student satisfaction and loyalty are in the center of the current research, indirect and total effects should also be examined in the model. The indirect effect of competences on foreign student loyalty (β = 0.225) materializes through university-related foreign student satisfaction (= 0.312*0.720), similarly to the effect of content of curriculum (β = 0.349) on loyalty (= 0.485*0.720).

Places to spend free time at has an indirect effect on foreign student loyalty (β = 0.037) via non-university-related foreign student satisfaction (= 0.275*0.135). Living in the city has a similarly weak but significant indirect effect on foreign student loyalty (β = 0.078) via non-university-related foreign student satisfaction (= 0.578*0.135). Based on the R2 values in the ellipses, the exploratory forces in the model could be considered moderately strong. It is important to highlight that even though the path coefficient is higher between university-related foreign student satisfaction and loyalty, than between non-university-related foreign student satisfaction and loyalty, the R2 value is higher in case of non-university-related foreign student satisfaction (R2 = 0.712) than that of university-related foreign student satisfaction (R2 = 0.541).

It is also important to highlight the significance of the effects between the variables in the model. This is based on the f2 indicator, which examines the change in the determination coefficient of the endogenous variable when an exogenous variable is omitted (Hair et al., 2014). Based on Table 2 it can be stated that weak, medium, and strong effects can be observed in the model. The effects of university-related foreign student satisfaction on foreign student loyalty and living in the city on non-university-related foreign student satisfaction can be considered strong. Medium effects can be observed between places to spend free time at and non-university-related foreign student satisfaction, and competences and university-related foreign student satisfaction. Additional and less strong effects should also be considered, as all these paths can be considered significant at a five percent significance level (Table 3).

In order to understand the examined institution’s foreign student loyalty deeper and to see if foreign student loyalty types can be differentiated between, factor and cluster analysis were conducted based on the loyalty scale items previously added to the survey as a result of previous in-depth interviews. Creating new variables was possible based on the reliability analysis. Therefore, foreign student loyalty scales were examined with Principal Component Analysis. The KMO value was 0.907 and according to the Bartlett’s test of sphericity, factor analysis could be conducted. After Varimax rotation a two-factor result was concluded and factor loadings above 0.5 were accepted (Hair et al., 1998; IRM, 2014). The first factor could be named as foreign student university loyalty, as items related to foreign student university were grouped together. The second factor included items connected to the foreign student experience of studying abroad, so it is named foreign student experience loyalty.

On the basis of the factor analysis, cluster analysis was conducted to determine the loyalty of respondents. Hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted with Ward method and Euclidean distance. The dendrogram suggested several clusters but based on the scatter plot diagram (Fig. 3), a three-cluster solution was accepted. The first cluster includes foreign students who seem to be more loyal towards the university, while the second involves those who are more loyal to the study-abroad experience. Therefore, the first cluster is named “university loyal foreign students” (41.5%) and the second is “experience loyal foreign students” (46.8%). Foreign students in the third cluster do not seem to be loyal towards either university or experience, so they are named “Not loyal foreign students” (11.7%).

These findings on clusters reveal those foreign students participating in the research can be categorized regarding their loyalty based on what they are loyal to. As the current study is not representative in nature, conclusions can only be drawn to the sample. Further cross tabs findings show that most university loyal students are fee payers and participate in undivided 5-year degree programs (e.g.: in the field of: medicine, law, dentistry), while experience loyal students come from bachelor’s, PhD, and undivided programs with scholarships (e.g.: in the field of music, economics, philology, or IT). Non-loyal students can be found on almost every program level, except for PhD programs. Foreign student loyalty was found to develop over time spent in a higher education institution, as foreign students tend to reflect on themselves as loyal, when they are in the middle or towards the end of their studies.

5 Discussion

This research introduces a new hypothetical model for understanding what factors influence foreign student satisfaction and loyalty. The novelty of the model lies in the fact that non-university-related factors influencing foreign student satisfaction are distinguished between. The model was tested with PLS path analysis and bootstrapping, which are widely accepted methods in HEI studies (El-Hilali et al., 2015; Giner & Rillo, 2016; Lee, 2010). Moreover, the study uncovered the categorization of foreign student loyalty at the examined university with the help of cluster analysis (Bennasar-Veny et al., 2020; Caliskan et al., 2013; Saenz et al., 2011; Sultan & Wong, 2013a).

The results show that foreign student expectations do not have a significant effect on neither university- (H1), nor non-university-related foreign student satisfaction (H2). These results contradict previous literature, which revealed significant effects thereof (Alves & Raposo, 2009; Shahsavar & Sudzina, 2017; Gregory, 2019; Pezeshki et al., 2020). Interestingly, tangibles had no effect on university-related foreign student satisfaction (H3a), as previously seen in the literature, where Mekic and Mekic (2016) found the opposite. Similarly to this, attitude did not influence university-related foreign student satisfaction (H3d), even though prior studies showed significant effects (Ahmed & Masud, 2014; Lenton, 2015). Neither reliability (H3e) nor delivery (H3f) affected university-related foreign student satisfaction, even though both Yousapronpaiboon (2014) and Chui et al. (2016) found otherwise. The same tendency appeared in connection with public facilities (H4c) and job opportunities (H4e). As contrary to previous findings (Aldemir & Gülcan, 2004; Mihanovic et al., 2016; Smith, 2020), no significant effects were found between them and university-related foreign student satisfaction.

Significant path findings correspond to previous higher education marketing literature, as teachers’ competences (H3b) and the content of the curriculum (H3c) have a significant effect on university-related foreign student satisfaction (El-Hilali et al., 2015; Lenton, 2015) and they also have an indirect effect on foreign student loyalty. Additionally, living in the city (H4a), the international environment (H4b) (Machado et al., 2011; Schertzer & Schertzer, 2004) and places to spend free time at (H4d) (Abdullah, 2006; Mihanovic et al., 2016) also have a significant effect on non-university-related foreign student satisfaction. Living in the city and places to spend free time at both have an indirect effect on foreign student loyalty as well. All in all, both non-university (H5) and university-related satisfaction (H6) have a strong effect on foreign student loyalty, the latter of which was already discussed in previous studies mostly related to service quality (Alves & Raposo, 2009; Shahsavar & Sudzina, 2017).

Foreign student loyalty was studied in depth, but contrary to certain previous literature (Douglas & Davies, 2008; Sultan & Wong, 2013a), not in a qualitative way. Even though previous studies revealed different loyalty clusters and categorizations of students (Gallyamova, 2018; Bennasar-Veny et al., 2020), new light is shed on foreign student loyalty with the differentiation of university-, experience foreign student loyalty and lack thereof. These findings could specifically be useful for the chosen university and might encourage other HEIs to investigate their foreign student loyalty deeper.

6 Conclusions and Implications

This research was undertaken to reveal what factors influence university- and non-university related foreign student satisfaction, and whether foreign student satisfaction has an effect on foreign student loyalty. The second aim of this paper was to investigate foreign student loyalty deeper. Returning to the aims declared at the beginning of this study, this research has identified that both university- and non-university-related foreign student satisfaction exist as latent variables, competences and content influencing university-related foreign student satisfaction; living in the city, international atmosphere, and places to spend free time at affecting non-university-related foreign student satisfaction. Both types of satisfaction were found to have an effect on foreign student loyalty. The second major finding was revealed by cluster analysis showing that university-, experience and lack of foreign student loyalty can be differentiated between in case of the examined foreign students.

These findings have significant implications for the understanding of how foreign student expectations could be defined and measured in higher education institutions. If defined as a basis for subjective comparison (Oliver, 1980) or a forecasting factor (Churchill & Surprenant, 1982), unbiased expectations could be asked from freshmen. Therefore, the measurement of foreign student expectations prior to or upon student arrival in the target country (Gerdes & Mallinckrodt, 1994) is suggested. However, if examined as recalled assumptions – as it was done in this paper – expectations can be biased and regarded as a constantly changing and developing phenomenon (whether asked from a second- or fifth-year student) and can further depend on the study phase and study-field of the foreign student (e.g.: expectations from the field of medicine or business) (Woodruff et al., 1983).

Taken together, the findings suggest that foreign student satisfaction relates to the whole study abroad experience and both university- (Alfy & Abukari, 2020; Moslehpour et al., 2020) and non-university-related satisfaction (Alfano et al., 2021; Mihanovic et al., 2016) can be defined and distinguished between. Even though in the current study only five variables (competences, content, international environment, living in the city, places to spend free time at) influenced foreign student satisfaction, non-significant path-related variables can be included in the overall study of foreign students, as results may vary based on foreign student study track, level, and phase.

The data of this study suggest that loyalty can be achieved through both university- and non-university-related satisfaction. Moreover, foreign student loyalty can be comprehended according to the complex approach, as it includes emotional attachment, commitment, and possible word-of-mouth recommendations (Oliver, 1999; Reichheld, 2003). The results of the cluster analysis further implies that there are different underlying factors of foreign student loyalty. As opposed to the suggestions on expectations and satisfaction, the research results on loyalty imply the possibility of measuring foreign student loyalty on an institution-wide sample, based on which similarities and differences between study fields and levels can be found.

The findings of this research provide insights for higher education institutions into foreign student expectations, satisfaction, and loyalty. The principal implication of the current study for higher education institutions is that the continuous measurement of these notions has to be supplemented with specific study track- and study phase-related research potentially examining different levels of studies (bachelor, master, PhD) separately. A joint analysis of foreign students was proven to be useful and provides grounds for further studies but has raised several questions to be investigated.

Finally, a number of important limitations need to be considered. First, the research included a lengthy online questionnaire. Another limitation lies in the fact that the paper relied on a convenience sample including foreign students from different study tracks and phases. Moreover, the results of this survey are limited solely to foreign students at a Hungarian university. Therefore, additional studies are recommended to test the applicability of the examined model more in depth and in different HEIs as well.

Although the current study is based on a small sample of participants, it offers insight into foreign student satisfaction and loyalty. The paper establishes a quantitative framework and model for the measurement of several constructs. This approach is hoped to prove useful in expanding our understanding of foreign student satisfaction and loyalty at higher education institutions in the future.

The main strength of this study is that it represents a comprehensive examination of foreign student satisfaction and loyalty. However, this research has also raised many questions in need of further investigation. Firstly, the study of a less complex cohort of foreign students is needed in case of expectations and satisfaction, including only one specific faculty or department, where foreign students may have similar backgrounds and interests (e.g.: in job opportunities). The current study investigated a university with 12 different faculties, where willingness to work besides studies may vary deeply among foreign students of medicine and business (Gallyamova et al., 2018). Secondly, significant paths – especially the novel one between non-university foreign student satisfaction and foreign student loyalty – should be investigated with foreign students from different academic programs and years separately to determine any differences that might arise from these factors mentioned. Thirdly, foreign student loyalty may either be studied as three separate latent variables (university loyalty, experience loyalty, and lack of loyalty), on which university-related, non-university-related and overall foreign student satisfaction’s effects could be measured, or an institution-wide sample should be drawn to highlight any differences between study fields and levels. The conceptual model set and tested in the current research could be the basis of studies conducted in specific faculties of the institution, and it could be further adapted to other universities in Hungary and Europe as well. Another direction could be to further research the reason why some foreign students are not loyal. This would enable the HEI to enhance service quality, possibly satisfy foreign student students’ needs to a greater extent and thereby retain them, as retaining a customer may be less expensive than attracting new ones (Reichheld, 1996). As mentioned above, the measurement of the constructs included in this study can be adopted at a faculty level and conducted at a regular basis to ensure continuous feedback and potential service improvement (Chui et al., 2016).

Change history

18 February 2022

Updated due to the missing funding.

References

Abdullah, F. (2006). The development of HedPERF: A new measuring instrument of service quality for the higher education sector. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 30(6), 569–581.

Ahmed, S., & Masud, M. M. (2014). Measuring service quality of a higher education institute towards student satisfaction. American Journal of Educational Research, 2(7), 447–455.

Aldemir, C., & Gülcan, Y. (2004). Student satisfaction in higher education: a Turkish case. Higher Education Management and Policy, OECD Publishing, 16(2), 109–122.

Alfano, V., Gaeta, G. & Pinto, M. (2021). Non-academic employment and matching satisfaction among PhD graduates with high intersectoral mobility potential, International Journal of Manpower, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJM-10-2020-0489

Alfy, S. E., & Abukari, A. (2020). Revisiting perceived service quality in higher education: Uncovering service quality dimensions for postgraduate students. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 30(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2019.1648360

Alsheyadi, A. K., & Albalushi, J. (2020). Service quality of student services and student satisfaction: The mediating effect of cross-functional collaboration. The TQM Journal, 32(6), 1197–1215. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-10-2019-0234

Alves, H., & Raposo, M. (2007). Conceptual model of student satisfaction in higher education. Total quality management, Universidade de Beira Interior, Covilhã, Portugal, 18, 5, 571–588.

Alves, H., & Raposo, M. (2009). The measurement of the construct satisfaction in higher education. Service Industries Journal, 29(2), 203–218.

Amaro, D. M., Marques, A. M. A., & Alves, H. (2019). The impact of choice factors on international students’ loyalty mediated by satisfaction. International Review of Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 16, (2), 211–233.

Bennasar-Veny, M., Yañez, A. M., Pericas, J., Ballester, L., Fernandez-Dominguez, J. C., Tauler, P., & Aguilo, A. (2020). Cluster analysis of health-related lifestyles in university students. International Journal of Environment Responsibility and Public Health, 5(17), 1776. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051776

Bryla, P. (2015). The impact of international student mobility on subsequent employment and professional career. a large-scale survey among polish former Erasmus students. Procedia, Social and Behavioral Sciences, 176, 633–641.

Buckner, E., & Stein, S. (2020). What Counts as Internationalization? Deconstructing the Internationalization Imperative. Journal of Studies in International Education, 24(2), 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315319829878

Byrne, M., & Flood, B. (2005). A study of accounting students’ motives, expectations and preparedness for higher education. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 29(2), 111–124.

Caliskan, Ö., Özgen, B. & Adigüzel M. B. (2013) Satisfaction and academic engagement among undergraduate students: a case study in Istanbul university. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science (2147- 4478), 2(4), 84–92. https://doi.org/10.20525/ijrbs.v2i4.83

Cardona, M. M., & Bravo, J. J. (2012). Service quality perceptions in higher education institutions: The case of a Colombian university. Estudios Gerenciales, 28, 23–29.

Cardozo, R. (1965). An experimental study of customer effort, expectation, and satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research, 2(3), 244–249.

Cheng, A. Y. (2014). Perceived value and preferences of short-term study abroad programmes: A Hong Kong study. Procedia, Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 4277–4282.

Chui, T. B., Ahmad, M. S., Bassim, F. A. & Zaimi, A. (2016) Evaluation of service quality of private higher education using service improvement matrix. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 224, 132–140.

Churchill, G. A., & Surprenant, C. (1982). An investigation into the determinants of customer satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Research, 19, 491–504.

Curran, V., Sharpe, D., Flynn, K., & Button, P. (2010). A longitudinal study of the effect of an interprofessional education curriculum on student satisfaction and attitudes towards interprofessional teamwork and education. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 24(1), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820903011927

de Souza Câmara, A. R. A., et al. (2020). Determinants of student satisfaction and loyalty among students from Brazilian Accounting Sciences graduate programs. Revista De Educação e Pesquisa Em Contabilidade, 14(1), 14–33. https://doi.org/10.17524/repec.v14i2.2474

Douglas, J., & Davies, J. (2008). The development of a conceptual model of student satisfaction with their experience in higher education. Quality Assurance in Education, 16(1), 19–35.

El-Hilali, N., Al-Jaber, S., & Hussein, L. (2015). Students’ satisfaction and achievement and absorption capacity in higher education. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 177, 420–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.02.384

Elkhani, N., & Bakri, A. (2012). Review on Expectancy Disconfirmation Theory (EDT) model in B2C e-commerce. Journal of Information Systems Research and Innovation, 2, 95–102.

Elliot, K. M., & Healy, M. A. (2001). Key factors influencing student satisfaction related to recruitment and retention. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 10(4), 1–11.

Faizan, A., Yuan, Z., Kashif, H., Pradeep, K., Nair, N., & Ari, R. (2016). Does higher education service quality effect student satisfaction, image and loyalty? A study of international students in Malaysian public universities. Quality Assurance in Education, 24, 1.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluation structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research. 18, 1, 39–50.

Gallyamova, I. R., Yusupova, N. I., Smetanina, O. N., & Uzbekova, L. Y. (2018). Analysis of Data to Determine Customer Loyalty in the Educational Sphere Using Kohonen Maps. International Scientific Journal Insutry, 4, 203–208.

Garwe, E.C. and Thondhlana, J. (2021) Making internationalization of higher education a national strategic focus, Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-09-2020-0323

Gerdes, H., & Mallinckrodt, B. (1994). Emotional, social, and academic adjustment of college students: A longitudinal study of retention. Journal of Counseling and Development, 72, 281–288.

Ghazarian, P. G. (2020) A Shared Vision? Understanding Barriers to Internationalization. Journal of Comparative & International Higher Education, 12(Fall), 99–123. https://doi.org/10.32674/jcihe.v12iFall.1839

Giner, G. R., & Rillo, A. P. (2016). Structural equation modelling of co-creation and its influence on the student’s satisfaction and loyalty towards university. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics, 291, 257–263.

Gregory, J. L. (2019). Applying SERVQUAL: Using service quality perceptions to improve student satisfaction and program image. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 11(4), 788–799. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-12-2018-0268

Gronholdt, L., Martensen, A., & Kristensen, K. (2000). The relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty: Cross-industry differences. Total Quality Management, 11(4–6), 509–514.

Hair, J. F., Jr., et al. (1998). Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings. Prentice-Hall.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publication.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate data analysis, 7th edition. Prentice Hall. Upper Saddle River.

Henseler, J., & ChristianSarstedt, M. R. M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135.

Huybers, T., Louviere, J., & Islam, T. (2015). What determines student satisfaction with university subjects? A choice-based approach. Journal of Choice Modelling, 17, 52–65.

I. R. M. (2014). Association, marketing and consumer behavior: concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications, IGI Global.

Jager, J., & Gbadamosi, G. (2013). Predicting students’ satisfaction through service quality in higher education. International Journal of Management Education, 11, 107–118.

Jiang, Q., Yuen, M. & Horta, H. (2020). Factors influencing life satisfaction of international students in Mainland China. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling 42, 393–413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-020-09409-7

Kakar, A. S., Mansor, N. N. A., & Saufi, R. A. (2021). Does organisational reputation matter in pakistan’s higher education institutions? The Mediating Role of Person-Organization Fit and Person-Vocation Fit between Organizsational Reputation and Turnover Intention, International Review of Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 18, 151–169.

Karemera, D., Reuben, L. J., & Sillah, M. R. (2003). The effects of academic environment and background characteristics on student satisfaction and performance: The case of South Carolina State University’s School of Business. College Student Journal, 37(2), 298.

Kazár, K. (2014). A PLS-útelemzés és alkalmazása egy márkaközösség pszichológiai érzetének vizsgálatára. Statisztikai Szemle, 92(1), 33–52.

Landrum, B., Bannister, J., Garza, G., & Rhame, S. (2021). A class of one: Students’ satisfaction with online learning. Journal of Education for Business, 96(2), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2020.1757592

Lee, J.-W. (2010). Online support service quality, online learning acceptance, and student satisfaction. Internet and Higher Education, 13, 277–283.

Lenton, P. (2015). Determining student satisfaction: An economic analysis of the national student survey. Economics of Education Review, 47, 118–127.

Letcher, D. Q. & Neves, J. S. (2010) Determinants of undergraduate business student satisfaction. Research in Higher Education Journal, 1–26.

Long, C. S., Ibrahim, Z., & Kowang, T. O. (2014). An analysis on the relationship between lecturers’ competencies and students’ satisfaction. International Education Studies, 7(1), 37–46.

Machado, M. L., Brites, R., Magalhaes, A., & Sá, M. J. (2011). Satisfaction with higher education: Critical data for student development. European Journal of Education, 46, 415–432.

Mekic E., & Mekic, E. (2016). Impact of higher education service quality on student satisfaction and its influence on loyalty: Focus on first cycle of studies at accredited HEIs in BH. ICESoS 2016, Proceedings, 43–56.

Mihanovic, Z., Batinic, A. B. & Pavicic, J. (2016) The link between students’ satisfaction with faculty, overall students’ satisfaction with student life and student performances. Review of Innovation and Competitiveness: A Journal of Economic and Social Research, 2(1), Ožujak 2016.

Moslehpour, M., Chau, K. Y., Zheng, J., Hanjani, A. N., & Hoang, M. (2020). The mediating role of international student satisfaction in the influence of higher education service quality on institutional reputation in Taiwan. International Journal of Engineering Business Management. https://doi.org/10.1177/1847979020971955

Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17, 460–469.

Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63, 33–44.

Oliver, R. L., & Bearden, W. O. (1985). Disconfirmation processes and consumer evaluations in product usage. Journal of Business Research, 13, 235–246.

Østergaard P. & Kristensen, K. (2005). Drivers of student satisfaction and loyalty at different levels of higher education (HE): Cross-institutional results based on ECSI methodology. In New perspectives on research into higher education: SRHE Annual Conference; 2005; Edinburg: University of Edinburgh.

Owlia, M. S., & Aspinwall, E. M. (1996). A framework for the dimensions of quality in higher education. Quality Assurance in Education, 4(2), 12–20.

Pedro, I. M., Mendes, J. C., Pereira, L. N., & Sequeira, B. D. (2020). Alumni’s Perception about Commitment Towards their University: Drivers and Consequences. International Review of Public and Nonprofit Marketing, 17, 469–491.

Pezeshki, E. R., & Sabokro Jalilian, M. N. (2020). Developing customer satisfaction index in Iranian public higher education. International Journal of Educational Management, 34(7), 1093–1104. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-11-2018-0378

Rehman, M. A., Woyo, E., Akahome, J. E., & Sohail, M. D. (2020). The influence of course experience, satisfaction, and loyalty on students’ word-of-mouth and re-enrolment intentions. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2020.1852469

Reichheld, F. F. (1996). Learning from customer defections. Harvard Business Review, 74, 56–69.

Reichheld, F. F. (2003). The one number you need to grow. Harvard Business Review, 81(12), 46–54.

Reichheld, F. F., & Sasser, W. E. (1990). Zero defections: Quality comes to services. Harvard Business Review, 68(5), 105–111.

Reichheld, F. F., Markey, R. G., Jr., & Hopton, C. (2000). The loyalty effect – the relationship between loyalty and profits. European Business Journal, 12(3), 134–139.

Restaino, M., Vitale, M. P., & Primerano, I. (2020). Analysing international student mobility flows in higher education: A comparative study on European countries. Social Indicators Research: An International and Interdisciplinary Journal for Quality-of-Life Measurement, Springer, 149(3), 947–965.

Ringle, C. M., Wende, S. & Becker, J.-M. (2015) SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH, Boenningstedt. http://www.smartpls.com

Saenz, V. B., Hatch, D., Bukoski, B. E., Kim, S., Lee, K., & Valdez, P. (2011). Community College Student Engagement Patterns: A Typology Revealed Through Exploratory Cluster Analysis. Community College Review, 39(3), 235–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091552111416643

Santos, G., Marques, C. S., Justino, E., & Mendes, L. (2020). Understanding social responsibility’s influence on service quality and student satisfaction in higher education, Journal of Cleaner Production, Volume 256. ISSN, 120597, 0959–6526.

Savitha, S. & Padmaja, P. V. (2017). Measuring service quality in higher education: application of ECSI model. International Journal of Commerce, Business and Management, 6, 5, Sep-Oct 2017.

Schertzer, C. B., & Schertzer, S. M. B. (2004). Student satisfaction and retention: A conceptual model. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 14(1), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1300/J050v14n01_05

Shahsavar, T. & Sudzina, F. (2017) Student satisfaction and loyalty in Denmark: Application of EPSI methodology. PLoS ONE 12 (12): e0189576.

Smith C. (2020) International Students and Their Academic Experiences: Student Satisfaction, Student Success Challenges, and Promising Teaching Practices. In: Gaulee U., Sharma S., Bista K. (eds) Rethinking Education Across Borders. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-2399-1_16

Sultan, P., & Wong, H. Y. (2013). Antecedents and consequences of service quality in a higher education context: A qualitative research approach. Quality Assurance in Education, 21(1), 70–95.

Turkyilmaz, A., Temizer, L., & Oztekin, A. (2018). A casual analytic approach to student satisfaction index modeling. Annals of Operations Research, 263(1–2), 565–585.

Van Mol, C., Caarls, K., & Souto-Otero, M. (2020). International student mobility and labour market outcomes: An investigation of the role of level of study, type of mobility, and international prestige hierarchies. High Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00532-3

Wiers-Jenssen, J., Stensaker, B., & Grogaard, J. B. (2002). Student satisfaction: Towards an empirical deconstruction of the concept. Quality in Higher Education, 8(2), 183–195.

Williams, R. (2020). The effect of casual teaching on student satisfaction: evidence from the UK. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3739417 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3739417

Woodruff, R., Cadotte, E., & Jenkins, R. (1983). Modeling Consumer Satisfaction Processes Using Experience-Based Norms. Journal of Marketing Research, 20(3), 296–304.

Yang, Z., Becerik-Gerber, B., & Mino, L. (2013). A study on student perceptions of higher education classrooms: Impact of classroom attributes on student satisfaction and performance. Building Environment, 70, 171–188.

Yousapronpaiboon, K. (2014). SERVQUAL: measuring higher education service quality in Thailand. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, pp. 1088–1095.

Zhai, X., Gu, J., Liu, H. Liang, J. & Tsai, C. C. (2017). An Experiential Learning Perspective on Students’ Satisfaction Model in a Flipped Classroom Context. Journal of Educational Technology & Society, 20(1), 198–210. Retrieved March 28, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.20.1.198

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Szeged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kéri, A., Hetesi, E. Is it only the university they are satisfied with? – Foreign student satisfaction and its effect on loyalty. Int Rev Public Nonprofit Mark 19, 601–622 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-021-00311-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12208-021-00311-5