Abstract

We use a unique microdata set that covers the 1984–2009 period to estimate real wage flexibility in Eastern and Western parts of Germany. Empirical analysis reveals that wages of male job stayers in the Eastern and Western parts of Germany are rigid, which leads to significant wage flexibility for internal and external movers. At the aggregate level, wages of the external movers are more flexible than the wages of job stayers in bust periods (when labour market is slack) and more rigid than the wages of job stayers in boom periods (when labour market is tight). In overall terms, the West German labour market is mature but conditions in the East German labour market are consistent with transition economies. Wage flexibility in Germany’s labour market can be attributed to relatively more flexible wages of the external and internal movers in a slack labour market.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Labour market flexibility describes how quickly and to what extent the labour market adapts to economic shocks (Maza and Villaverde 2009) including adjustments in quantities (work hours flexibility and employment flexibility) and prices (wage flexibility). Wage flexibility is the ability of wages to equilibrate demand and supply in different labour market categories (Onaran 2002). Hence, wage flexibility is defined as the speed with which real wages respond to macroeconomic conditions such as the unemployment variations (Clar et al. 2007). In periods of increasing unemployment, wages should be adjusted downwards, which increases the demand for labour but the labour supply decreases, which allows the labour market to return its equilibrium and vice versa. Thus, wage flexibility is a key adjustment mechanism that determines the labour market flexibility. Wage flexibility can be measured by the adjustment of wages over the business cycle (Bils 1985; Grant 2003).

Features of a labour contract generally depend on whether or not the outcomes of a worker’s activities can be observed. Agreed outcomes that are verifiable are normally explicitly stated in the contract. If the outcomes are not verifiable, the working relationship is governed by an implicit contract (Azariadis 1975; Carmichael 1989; Cahuc and Zylberberg 2004). Through an implicit contract, the employer attempts to protect the workers from the adverse effects of changes in economic conditions. Thus, an implicit wage contract can be viewed as an insurance contract, which is designed to shield the workers from business cycle fluctuations. Such contracts are characterized by an implicit understanding between the parties concerning the salary and working conditions (Bertrand 2004; Devereux and Hart 2007).

In a spot labour market, employment involves a sequential exchange of labour services for money (Azariadis 1975; Baily 1974; Gordon 1974). In such a market, (i) wage contracts involve a rather short time period and hence must be frequently re-negotiated and (ii) compensation is largely determined by the marginal revenue product of workers and the prevailing economic conditions (Devereux and Hart 2007). Peeters and den Reijer (2014) argue that productivity is the main determinant of wages in Germany.

See Devereux and Hart (2006).

Nickell and Quintini (2003) find that around 20% of the job stayers experienced nominal wage cuts annually during the 1990s. They also point to high wage flexibility of the job stayers in the UK. Fallick et al. (2016) also find that nominal wage rigidity has been lower in recent years than in earlier decades in the US. Snell et al. (2018) argue that elasticity of real wages with respect to business cycle is large and significant in upswing for incumbent workers in Germany.

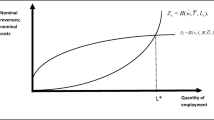

Instead of reproducing the entire Beaurdy and DiNirado model in this section, we only describe the main elements of the model and use their results to derive some testable hypotheses.

Using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) and the Current Population Survey (CPS) data from the US, Beaudry and DiNardo (1991) find empirical support for their model. The empirical work of Grant (2003), which relies on the National Longitudinal Survey (NLS) data, also provides a strong support for Beaudry and DiNardo’s key predictions.

For simplicity, the agents (i.e., firms and households) are assumed to have an identical discount rate and the probability of death (See Beaudry and DiNardo 1991).

Labour market segmentation in Germany can be attributed to a number of factors. For example, the barriers among enterprises/industries/sectors (Deutschmann 1981; Garz 2013). Labour market segmentation can also be observed between the natives and immigrants in some occupations (Constant and Massey 2005). Other factors that contribute to labour market segmentation include (i) the region of origin (Grünert and Lutz 1995; Felbo-Kolding et al. 2019) and job classifications (e.g., standard versus non-standard employment as indicated by Garz 2013). The division of labour and barriers between segments not only make external job mobility costly but also increase earning disparity.

Using the same dataset, Sommerfeld (2013) consider the issue of performance pay in Germany.

An important advantage of panel data collected from GSOEP is that we can distinguish among the job stayers, internal movers and external movers.

Following Ammermuller et al. (2010), we use a one year lag of the unemployment change variable, Δut-1.

Although the GSOEP East started in 1990, no information on worker employment is 1990 and 1991 is available. Accordingly, the data for East Germany used in this paper cover the 1992–2009 period.

A parallel to the West-East wage gap in Germany can be observed in the US labour market, where even with similar educational attainment and work experience, on average, immigrants earn lower wages than natives. However, there is evidence that the wage gap between immigrants and natives falls over time in the US labour market (Chiswick 1978; Borjas 1985; LaLonde and Topel 1992). The decrease in the wage gap can be attributed to the flexibility of labour market institutions in the US, where immigrants are able to earn higher wages by accumulating on-the-job human capital and through job search (Lessem and Sanders 2013). Furthermore, using the population survey data from 1979 and 1989, Trejo (2020) finds that, compared to other workers in the US, a significant proportion of this wage gap can be attributed to relatively lower educational attainment by Mexican Americans.

Stüber (2017), among others, highlighted the importance of job movement in wage flexibility studies. Stüber argued that failure to control for cyclical job movement could lead to spurious wage flexibility. Empirical assessment of wage flexibility requires an approach that identifies job up- and downgrading. Hence, categorisation of the respondents into job stayers, internal and external movers is necessary to control job movement.

Bils (1985) and Shin (1994) note that wage flexibility is especially pronounced among job movers in the US, which is like the situation in West Germany, where job movers enjoy wage gains in boom periods but suffer from wage losses in recessionary periods. However, Bowlus (1995), Shin (1994), Solon et al. (1994), and Shin and Shin (2008) also found substantial wage flexibility for job stayers in the US, which implies that a compensating differential model in more relevant in the American labour market.

Because of the core-periphery segmentation of the labour force in Germany (Cornelißen and Hübler 2008; Garz 2013; Stüber 2017; Snell et al. 2018), the situation for women differs from that of men. A core work force (e.g., male workers in the West, with implicit contracts) is protected from wage cuts, internal demotions and layoffs. On the other hand, the peripheral work force (e.g., female workers in the East) serves as a buffer that helps to provide wage flexibility in the event of adverse economic shocks. The peripheral work force in Germany faces wage cuts, internal demotion and higher level of job insecurity. Garz (2013) report that the share of female employees in the secondary sector increased by nearly 5 percentage points over the 2001–2005 period. In the post- (labour market) reform period, the secondary sector appears to provide wage flexibility to a greater extent. In overall terms, the secondary sector is characterized by non-standard jobs, which are mostly occupied by female workers who are relatively poorly paid. Such jobs are unstable even in the internal labour market. To reduce the chances of job loss, female workers tend to prefer internal demotion over external job movement. Thus, internal job movement has a negative impact on the female wage growth, especially in the bust periods (−2.87) in the West. This effect is more pronounced (−5.269) in the East. The results presented in Table 4 exhibit the segmented market and periphery working conditions for females and workers in East Germany.

References

Addison JA, Bryson A, Teixeira P, Pahnke A (2011) Slip Sliding Away: Further Union Decline in Germany and Britain. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 58(4):490–513

Agudelo SA, Sala H (2017) Wage rigidities in Colombia: Measurement, causes, and policy implications. J Policy Model 39(3):547–567

Ammermuller A, Lucifora C, Origo F, Zwick T (2010) Wage flexibility in regional labour markets: Evidence from Italy and Germany. Reg Stud 44(4):401–421

Anger S (2011) The Cylicality of Effective Wages within Employer-Employee Matches in a Rigid Labor Market. Labour Econ 18(6):786–797

Antonczyk D, Fitzenberger B, Sommerfeld K (2010) Rising wage inequality, the decline of collective bargaining, and the gender wage gap. Labour Econ 17(5):835–847

Azariadis C (1975) Implicit Contracts and Underemployment Equilibria. J Polit Econ 83:1183–1202

Baker G, Gibbs M, Holmstrom B (1994) The Wage Policy of a Firm. Q J Econ 109(4):921–955

Baily M (1974) Wages and employment under uncertain demand. Review of Economic Studies 41(1):37–50

Barlevy G (2001) Why Are the Wages of Job Changers So Procyclical? J Labor Econ 19(4):837–878

Beaudry P, DiNardo J (1991) The effect of implicit contracts on the movement of wages over the business cycle: evidence from micro data. J Polit Econ 99(4):665–688

Bentivogli C, Pagano P (1999) Regional disparities and labour mobility: the euro-11 versus the USA. LABOUR 13(3):737–760

Bertrand M (2004) From the Invisible Handshake to the Invisible Hand? How Import Competition Changes the Employment Relationship. J Labor Econ 22(4):723–765

Bils MJ (1985) Real Wages over the Business Cycle: Evidence from Panel Data. J Polit Econ 93(4):666–689

Blanchflower DG, Bryson A (2010) The wage impact of trade unions in the UK public and private sectors. Economica 77(305):92–109

Borjas GJ (1985) Assimilation, changes in cohort quality, and the earnings of immigrants. J Labor Econ 3(4):463–489

Bowlus AJ (1995) "Matching Workers and Jobs: Cyclical Fluctuations in Match Quality," Journal of Labor Economics 13(2):335–350

Burda, M.C. (2016), The German Labor Market Miracle, 2003–2015: An Assessment. SFB 649 Discussion Paper 2016–005. Berlin, Germany

Cahuc P, Zylberberg A (2004) Labor Economics. MIT Press, Cambridge

Carmichael L (1989) Self-enforcing contracts, shirking, and life cycle incentives. Journal of Economics Perspectives 3:65–84

Chiswick B (1978) The effect of Americanization on the earnings of foreign-born men. J Polit Econ 86:897–921

Clar M, Dreger C, Ramos R (2007) Wage flexibility and labour market institutions: a meta-analysis. Kyklos 60(2):145–163

Cornelißen T, Hübler O (2008) Downward wage rigidity and job mobility. Empir Econ 34(2):205–230

Constant A, Massey DS (2005) Labor market segmentation and the earnings of German guest workers. Population Research & Policy Review 24(5):489–512

Deutschmann C (1981) Labour market segmentation and wage dynamics. Manag Decis Econ 2(3):145–159

Devereux PJ, Hart RA (2006) Real Wage Cyclicality of Job Stayers, Within-Company Job Movers, and Between-Company Job Movers. Ind Labor Relat Rev 60:105–119

Devereux PJ, Hart RA (2007) The spot market matters evidence on implicit contracts from Britain. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 54(5):661–683

DIW. (2010a). Documentation PGEN. Person-related status and generated variables. The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) Survey 2009

DIW. (2010b). Living in Germany. Survey 2009 on the social situation of households. The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) Survey 2009

Doménech R, García JR, Ulloa C (2018) The effects of wage flexibility on activity and employment in Spain. J Policy Model 40(6):1200–1220

Dustmann C, Fitzenberger B, Schönberg U, Spitz-Oener A (2014) From Sick Man of Europe to Economic Superstar: Germany's Resurgent Economy. J Econ Perspect 28(1):167–188

Elsby MWL, Shin D, Solon G (2016) Wage Adjustment in the Great Recession and Other Downturns: Evidence from the United States and Great Britain. J Labor Econ 34(S1 Part 2):S249–S291

Fallick BC, Lettau M, Wascher WL (2016) Downward nominal wage rigidity in the United States during and after the great recession. Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2016–001. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, https://doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2016.001

Felbo-Kolding J, Leschke J, Spreckelsen TF (2019) A division of labour? Labour market segmentation by region of origin: the case of intra-EU migrants in the UK, Germany and Denmark. J Ethn Migr Stud 45(15):2820–2843

Franz W, Pfeiffer F (2006) Reasons for Wage Rigidity in Germany. Labour 20(2):255–284

FSO. (2011). Labour market statistics, unemployment rates by area, Federal Statistics Office, USA

Garz M (2013) Labour Market Segmentation: Standard and Non-Standard Employment in Germany. Ger Econ Rev 14(3):349–371

Gordon D (1974) An neo-classical theory of Keynesian unemployment. Econ Inq 12(4):431–459

Grant D (2003) The effect of implicit contracts on the movement of wages over the business cycle: evidence for the National Longitudinal Surveys. Industrial and Labour Relations Review 56(3):393–408

Grünert H, Lutz B (1995) East German labour market in transition: segmentation and increasing disparity. Ind Relat J 26(1):19–31

Hall RE (1974) The process of inflation in the Labour Market. Brook Pap Econ Act 2:343–393

Hashimoto M (1979) Bonus payments, on-the-job training, and lifetime employment in Japan. J Polit Econ 87(5):1086–1104

Heckman JJ (1976) The common structure of statistical models of truncation, sample selection and limited dependent variables and a simple estimator for such models. Ann Econ Soc Meas 5:475–492

Heckman JJ (1979) Sample Selection Bias as a Specification Error. Econometrica 47(1):153–161

Heckman JJ (2001) Micro data, heterogeneity, and the evaluation of public policy: Nobel Lecture. J Polit Econ 109:673–748

Heckman JJ, Sedlacek G (1985) Heterogeneity, Aggregation, and Market Wage Functions: An Empirical Model of Self-selection in the Labor Market. J Polit Econ 93:1077–1125

Hirsch BT (2004) Reconsidering Union Wage Effects: Surveying New Evidence on an Old Topic. J Lab Res 25(2):233–266

Hirsch B, Zwick T (2015) How selective are real wage cuts? a micro-analysis using linked employer–employee data. Labour 29(4):327–347

Hubler O, Jirjahn U (2003) Works Councils and Collective Bargaining in Germany: The Impact on Productivity and Wages. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 50:471–491

Izquierdo, M., Jimeno, J. F., Kosma, T., Lamo, A., Millard, S., & Rõõm, T., et al. (2017). Labour market adjustment in Europe during the crisis: microeconomic evidence from the wage dynamics network survey. European Central Bank. ECB Occasional Paper, No.192

Kang L, Peng F (2017) Wage flexibility in the Chinese labour market, 1989–2009. Reg Stud 51(4):616–628

Kenworthy L (2001) Wage-setting Measures: A Survey and Assessment. World Polit 54:57–98

Kluge J, Weber M (2018) Decomposing the German East–West Wage Gap. Econ Transit 26(1):91–125

LaLonde RJ, Topel RH (1992) Assimilation of immigrants in the U.S. labor market. In Borjas, G. J. and Freeman, R. B., editors, Immigration and the Work Force. The University of Chicago Press

Lessem R, Sanders C (2013) Decomposing the native-immigrant wage gap in the United States. Sci Rep 3(10):2866–2866

Maza A, Villaverde J (2009) Provincial wages in Spain: Convergence and flexibility. Urban Stud 46(9):1969–1993

Matysiak A, Steinmetz S (2008) Finding Their Way? Female Employment Patterns in West Germany, East Germany, and Poland. Eur Sociol Rev 24(3):331–345

Martins PS (2007) Heterogeneity in real wage cyclicality. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 54:684–698

Moulton BR (1986) Random Group Effects and the Precision of Regression Estimates. J Econ 32:385–397

Nickell S, Quintini G (2003) Nominal wage rigidity and the rate of inflation. Economic Journal 113:762–781

Ochel W (2005) Decentralizing Wage Bargaining in Germany - A Way to Increase Employment? Labour 19(1):91–121

OECD. (2004). How does the United States compare? OECD Employment Outlook 2004

Onaran O (2002) Measuring wage flexibility: The case of Turkey before and after structural adjustment. Appl Econ 34(6):767–781

Panagiotidis T, Pelloni G (2003) Testing for non-linearity in labour markets: the case of Germany and the UK. J Policy Model 25(3):275–286

Peeters M, den Reijer A (2014) Coordination versus flexibility in wage formation: a focus on the nominal wage impact of productivity in Germany, Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and the United States. Appl Econ 46(7):698–714

Peng F, Siebert WS (2007) Real Wage Cyclicality in Germany and the UK: New Results Using Panel Data. IZA DP No. 2688

Peng F, Siebert WS (2008) Real wage cyclicality. Labour 22(4):569–591

Pino G, Soto A (2014) Analysis of wage flexibility across the Euro Area: evidence from the process of convergence of the labour income share ratio. Appl Econ 46(29):3572–3580

Piore MJ (1979) Birds of passage: Migrant labor and industrial societies. Cambridge University Press, New York

Reder MW (1955) The Theory of Occupational Wage Differentials. Am Econ Rev 45:833–852

Rosenfeld RA, Trappe H, Gornick JC (2004) Gender and Work in Germany: Before and After Reunification. Annu Rev Sociol 30:103–124

Shin D (1994) Cyclicality of real wages among young men. Econ Lett 46:137–142

Shin D, & Shin K (2008) "Why Are The Wages of Job Stayers Procyclical?," Macroeconomic Dynamics 12(1):1–21

Shin D, Solon G (2007) New Evidence on Real Wage Cyclicality Within Employer-Employee Matches. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 54(5):648–660

Snell A, Stüber H, Thomas JP (2018) Downward real wage rigidity and equal treatment wage contracts: theory and evidence. Rev Econ Dyn 30:265–284

Solon G (1988) Self-selection bias in longitudinal estimation of wage gaps. Econ Lett 28(3):285–290

Solon G, Barsky R, Parker JA (1994) Measuring the Cyclicality of Real Wages: How Important Is Composition Bias? Q J Econ 109:1–26

Solon G, Whatley W, Stevens AH (1997) Wage Changes and Intracompany Job Mobility over the Business Cycle: Two Case Studies. Ind Labor Relat Rev 50:402–415

Sommerfeld K (2013) Higher and higher? Performance pay and wage inequality in Germany. Appl Econ 45(30):4236–4247

Stüber H (2017) The real wage cyclicality of newly hired and incumbent workers in Germany. Economic Journal 127(600):522–546

Stüber H, Beissinger T (2012) Does downward nominal wage rigidity dampen wage increases? Eur Econ Rev 56(4):870–887

Traxler F (2003) Bargaining (De)centralization, Macroeconomic Performance and Control over the Employment Relationship. Br J Ind Relat 41(1):1–27

Trejo SJ (2020) Why Do Mexican Americans Earn Low Wages? Labour Economics, 62, Article No. 101771

Visser J (2009) Database on Institutional Characteristics of Trade Unions, Wage Setting, State Intervention and Social Pacts in 34 Countries between 1960 and 2007. Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies AIAS, University of Amsterdam

WEF (2011) The Global Competitiveness Report 2010–11. World Economic Forum, Geneva

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for very helpful comments and suggests. We are also grateful to several colleagues at the WPEG, NIESR, IE-SEBA and EALE Conferences for comments on earlier drafts. Fei Peng thanks the Shanghai Young Eastern Scholarship (QD2015049) for financial support. Lili Kang thanks the financial aid received from China National Social Science Fund (No. 14BJL028) and Shanghai ShuGuang Scholarship (15SG53). The German Socio-Economic Panel Data (GSOEP) is used with the permission of the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin). Neither the original collectors of the data nor the distributors bear any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented in this paper. All remaining errors are our own responsibility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors confirm that manuscript complies with ethical standards. No part of this paper has published, and it is not submitted to another journal.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, F., Anwar, S. & Kang, L. Job Movement and Real Wage Flexibility in Eastern and Western Parts of Germany. J Econ Finan 44, 764–789 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-020-09516-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-020-09516-6