Abstract

A concern across many vocational education systems is the high dropout rate from their programs. This problem is likely to be exacerbated at time of low unemployment rates when employers are less demanding about the certification of skills at the time of employment. This qualitative study examines the factors associated with students leaving early from Initial Vocational Education and Training (IVET) institutions in Estonia. The study analyses the challenges and potential risk factors of IVET early leaving from both the students and staff members points of view. The research participants were 20 Estonian IVET students and 12 staff members from various vocational schools. The study highlights the complex interplay of students’ challenges and emphasises the importance of addressing them to promote retention and success in vocational education and training programmes. The study employs the Self-Determination Theory, more specifically, the conceptual frame of basic psychological needs to interpret the data. The results of the research indicate that students at risk are mainly shaped by their primary school experience prior to vocational school, with teachers and peers as the main influencers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Problem of Non-completion invIVET

A concern across many vocational education systems is the high dropout rate from their programs. Yet, despite numerous studies examining the reasons for dropping out, high levels of dropouts in vocational schools continue to be a persistent issue in many countries (Krötz & Deutscher, 2022). According to Eurostat (2022), the rate of early leaving from vocational schools has been decreasing consistently from 13.8% in 2010 to 9.7% in 2021. However, the progress has slowed down since 2016, and there are significant differences across countries, regions, genders, and specific population groups, such as migrants, as reported by Cedefop (2022). High dropout rates are prevalent in Estonia at the secondary education level, especially in vocational education, with only 50% of students acquiring vocational education in nominal time (Serbak, 2018). School dropout is caused by various factors at different levels, and it increases the risk of long-term unemployment, poverty, and criminal behaviour (Reiska, 2018). Students who are at risk of failing to complete school are more likely to face social exclusion and unemployment, as identified in the Estonian Lifelong Learning Strategy 2035 report by the Ministry of Education and Research (HTM, 2020; Novosel et al., 2012). Factors that contribute to early leaving from vocational schools can differ depending on the perceptions of students and staff in the vocational schools. Therefore, it is important to consider multiple perspectives when addressing early leaving from initial education and training to identify and address the underlying causes effectively. By understanding the nature of the problem from different perspectives, we can better support young people, plan interventions, and implement changes at the teacher, school, or institutional level. Incorporating these different perspectives may also contribute to addressing broader issues, such as designing more effective policies for initial vocational education and training.

The aim of this paper is to provide an overview of the challenges that Estonian vocational school students perceive during their initial vocational education and training. Furthermore, to understand and highlight these challenges from both students’ and teachers’ perspectives, providing a comprehensive view of their experiences and identifying overlaps. This analysis provides valuable insights that can contribute to the improvement of the educational environment, curricula and support mechanisms for both students and teachers of Estonian vocational schools.

This study was guided by the following research questions:

-

How do IVET students experience challenges in a vocational school?

-

What are the challenges of IVET students as perceived by vocational school staff?

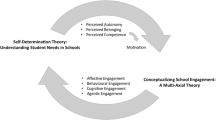

The Self-Determination Theory (SDT) (Ryan & Deci, 2017) has been applied as a conceptual framework enabling to interpret the results of this study and relate many of the challenges with the limited satisfaction of students´ basic psychological needs.

Reasons for Early Leaving from IVET in Estonia

IVET provides practical learning opportunities and a pathway to specific professions, which may be an attractive option for many young people (Schmid & Garrels, 2022). Despite a long-standing tradition of researching reasons for drop-out rates in IVET, they remain high in many countries (Krötz & Deutscher, 2022). The problematic aspect of this issue is that dropout is not just a concern of the school system; it has ramifications that extend to the entire community. According to other studies, young people who drop out of vocational school are more prone to remaining unemployed, living in impoverished conditions, and relying on state financial support. Additionally, students who leave school prematurely are more likely to encounter health issues and engage in criminal activities (Korumaz & Ekşioğlu, 2022). Eurostat data indicates that the EU early leaving rate from IVET for individuals aged 18–24 was 11.4% in 2021. This means that about 11.4% of individuals who began IVET did not complete their studies. In Estonia, the school dropout rate from IVET has become a growing concern, with an annual dropout rate of approximately 20% among all vocational education learners. The largest interruption of studies occurs in the first academic year and is significantly higher among male students (Haaristo & Kirss, 2018). According to Statistics Estonia (2022), there were a total of 5,823 vocational school dropouts in Estonia in 2021, which has increased by 9.4% compared to 2020 (Ibid). Numerous studies have demonstrated that the reasons for school dropout are multifaceted and cannot be attributed to a single factor (Jaggo, 2019; Espenberg et al., 2012; Cedefop, 2016; Böhn & Deutscher, 2022). Espenberg et al. (2012) have analysed the reasons for dropping out of vocational schools from the students’ point of view and divided them as follows: reasons related to the person himself or herself; family; vocational school or economic situation.

Additionally, Jaggo (2019) notes that incorrect programme or profession choices are a contributing factor to IVET dropouts. In Estonia, the most common reasons reported by vocational schools were difficulties with managing studies (46%), other reasons (33%), non-attendance (8%), employment or economic reasons (6%), unsuitable programme (4%), and health reasons (2%) (Jaggo, 2019). Böhn and Deutscher (2022) argue that high dropout rates have multiple reasons, including the mismatch between vocational education and the practical training offered in placements. Their study focuses on examining the alignment of education in vocational schools with practical training. According to Serbak (2018) and the findings from Espenberg et al., 2012 research, a contributing factor to the high dropout rate in vocational schools is the inadequate education level in general subjects. Furthermore, Haaristo and Kirss (2018) highlight that a lack of study motivation is another significant factor in students discontinuing their studies in vocational education. Studies have identified the parental socioeconomic position, such as education level, occupational prestige, and family income, as a strong risk factor for dropout (Evans et al., 2010; Lareau, 2003). Apparently, nothing other than dropping out significantly impacts students’ lives after school. Dropout becomes a challenge not only for the school system but also for the entire community (Korumaz & Ekşioğlu, 2022). Students who drop out face numerous difficulties in their lives because, without the necessary skills, knowledge, and certainly education, finding employment becomes challenging. Consequently, there is a ned to find explanations to understand and respond to this problem. Here, Self-Determination Theory is advanced as a means by which this might occur.

Self-Determination Theory and the Concept of the Basic Psychological Needs

The Self-Determination Theory (SDT) and the concept of the basic psychological needs is used as a frame for analysing and interpreting the research findings. Self-determination means the ability or process to make one’s own decisions and manage one’s life. Deci and. Ryan (2000) developed a theory of motivation suggesting that people are driven by the need to grow and fulfil themselves (Ryan & Deci, 2017). SDT suggests that people are motivated to grow and change by innate psychological needs and when these needs are met, individuals are more likely to be motivated, engaged, and successful in their pursuits. The ideas of the theory enable to explain vocational school dropout by emphasising people’s need for motivation and control. It highlights three interconnected psychological needs – autonomy, competence, and relatedness – that increase motivation and success when met.

Autonomy is about feeling in control of one’s actions, whether motivated by personal interests or external values. It is not the same as independence. (Ryan & Deci, 2002; Wilson, 2014) For young people, it is not only about wanting independence, but also about support to exchange their ideas with those of adults. How well a person integrates external motivations with their beliefs determines how well they feel in control. For example, a young person who understands the importance of homework, even if they dislike it, is likely to feel more in control than someone who does it just to avoid problems. When frustrated, one experiences a sense of pressure and often conflict, such as feeling pushed in an unwanted direction (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020).

Competence refers to the need to feel effective in coping with the social and physical environment, to look for opportunities to use and present one’s abilities. It is not just about acquiring skills; it means self-confidence and belief in one’s abilities. Like autonomy, supporting this need helps internalise extrinsic activities and leads to higher intrinsic motivation. (Ryan & Deci, 2002; Wilson, 2014) If a person feels incompetent in a task, they are less likely to take it on board, and negative feedback can reduce motivation and engagement. In essence, competence means that a young person feels capable and confident to cope with challenges. When frustrated, one experiences a sense of ineffectiveness or even failure and helplessness (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020).

Relatedness is about feeling connected to others, caring for them, and belonging to a group or community. According to the Self-Determination Theory, people tend to adopt the values of their social groups. In order for young people to follow and recognise school rules, they need to feel connected (connected) and capable (competent). (Ryan & Deci, 2002; Wilson, 2014) When this happens, their behaviour is more likely to be motivated and aligned with the school’s values. Relatedness frustration comes from a sense of social alienation, exclusion, and loneliness (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020).

SDT has been utilised in various studies to investigate students’ perceptions of the motivation of teaching skills through reading and storytelling and their experiences of satisfying psychological needs (Jeno et al., 2022). Consistent with SDT, previous research has demonstrated a positive relationship between the satisfaction of basic psychological needs and indices of well-being (e.g. life satisfaction & vitality), and a negative relationship with indicators of ill-being (e.g. depression) (Vansteenkiste & Van den Broeck, 2015). The theory has been widely applied in different contexts, including learning, work, and health behaviours (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013). SDT theory may be able to provide an understanding of why vocational school students may struggle to stay motivated or remain in school and can assist in developing interventions to address these needs. Hence, we have adopted it for the investigation whose method and findings are discussed here.

Methodological Approach

This qualitative study used data from the research project “EmpowerVET”Footnote 1 to improve the social inclusionFootnote 2 of at-risk young people through initial vocational education and workplace training. In this research, the socio-ecological approach is used as the framework basis for formulating the interview questions. The use of a social-ecological approach (Brofenbrenner´s ecological system theory of 1979) helps to contextualise and integrate the social and environmental dimensions, thereby contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the studied phenomena. Social ecology, viewed as a methodological approach rather than a fixed theory, is applied to analyse complex phenomena (Weaver-Hightower, 2008; Evans et al., 2014). There are two main analytical directions: Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system theory, which focuses on the development of the individual in an interdependent five-level environment (Lörinc et al., 2020); and macro-level analysis that examines organizations, social groups, and politics (Evans et al., 2014; Weaver-Hightower, 2008). Both directions emphasize the dynamic and multi-level interdependencies for the effective functioning and sustainability of the ecological approach.

In the research questions guiding this study, the focus is on the circumstances affecting the development of the individual and the mutual adaptation of their changing living conditions in the environment. The topics for the interview questions with students comprised biographical information; information about family members, education experience in primary school and in vocational school; satisfaction with the study field; future career perspectives; friends´ and family´s support; activities or hobbies outside the home and vocational school; vocational school´s support; internship possibilities; ability to influence what happens in school and society; online communities.

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews with students and staff from IVET institutions in Estonia, with a focus on staff members working in vocational schools with at-risk students. The study used a combined purposive and snowball sampling strategy to select participants for individual and group semi-structured interviews (Bryman, 2016). Management personnel from the schools were contacted via email to suggest staff who could participate in the research. Students were recommended by school representatives, including vocational school teachers and other employees and some students were also recommended among their peers. The approach enabled the inclusion of diverse perspectives and experiences in the data collection process. Prior to conducting the study, an ethics approval was obtained and all respondents provided informed consent before participating in the interviews. With a sample of 20 vocational students, aged between 16 and 24 years, individual Zoom interviews were conducted. Each interview lasted from 50 to 60 min, and all interviews were conducted in the Estonian language. Written consent was obtained from each participant for voice recording and automatic transcription prior to the interviews. Since the target group of the study included also 16-year-old minors, their parent´s written permission in addition to the written consent received from the students themselves was asked so that students could participate in the study. The sample of the interviewees included students (7) from various vocational schools in Estonia, who had dropped out of several schools but were currently enrolled in a specific vocational school, as well as students (13) who were at risk of dropping out of vocational education. The study involved students studying IT, administration, hairdressing, construction, landscaping, business management, art, and cooking. In addition to students, individual (6) and focus group (2) interviews with school staff were conducted to understand their perspective. In total, 12 staff members were interviewed, mainly teachers, but some of the teachers were also involved in other roles in the same vocational school for example as quality manager, head of educational affairs or project manager. The interviews lasted between 50 min and an hour. The questions asked during the interviews focused on topics such as students´ at-risk factors and support practices, strategies for dropout prevention, collaboration between stakeholders, and challenges related to vocational education for at-risk students.

All interviews were recorded, transcribed, systematised, and coded for analysis. Anonymity was ensured by replacing all names with pseudonyms. This study employs a hybrid approach to analysis, initially commencing with an inductive, text-driven analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). In the next step, noticeable themes were categorised into elements based on the underlying theory. The text-driven analysis revealed identifiable patterns aligning with the principles of the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) and the Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction (BPNS) approach focusing on autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Vansteenkiste et al., 2020).

Analysis and Findings

This section will outline students challenges that could potentially lead to dropping out of vocational school based on the interviews with students and staff. These are reported under eight headings: (i) Students lack of interest and motivation in their chosen field of study or speciality; (ii) Students’ learning challenges and participation in the classes and (iii) Challenges regarding internship; (iv) Challenges related to self-esteem and mental health problems; and (v) Poor social relations with friends, classmates and teachers in vocational school; (vi) Challenges related to the student’s poor social relationships in the family; vii). Challenges in combining work and study and viii) Challenges related to addiction to smart devices and computer games. Each of these is now discussed in turn.

1. Students Lack of Interest and Motivation in Their Chosen Field of Study or Specialty

The findings revealed that a large number of students (16 out of 20 students) have chosen their programme not out of interest but to secure admission and obtain a diploma. Low motivation in the chosen field was a shared concern among both students and vocational school staff. Motivation is an important element of success and failure in school and motivation depends on various factors. According to the given study, a decline in motivation may be attributed to the choice of field of study, which young individuals may have made rather superficially.

“I’m interested in the profession I’m studying, but whether I’ll go for the job in the future, it’s a bit doubtful. ….my parents suggested me to go to that vocational school” (Ken, age: 19; study field: Landscape-gardening, 3rd year; at risk of dropping out, as identified by teachers).

Based on the results of the interviews, it can be stated that the students’ choice of the study programme may have been made without much thought. The findings suggest that a significant number of students (15 out of 20 students) select their field of study based on parental, acquaintances or friends’ recommendations rather than personal interest.

However, if the student’s chosen course of study is influenced by parental or friends’ suggestions, it can lead to internal frustration for the student. This is because they may not have been able to satisfy their need for autonomy, as the decision-making process might have been driven by external influence rather than personal interests or internal motivation. 8 out of 20 students who participated in the interviews got the true understanding of the profession during their internship and it was different from their imagination. It can also be argued that the students did not have a sufficient overview of the profession or had a different idea of the profession, and it may also be possible that they did not gather enough information for themselves about what this particular profession represents.

“I’m currently studying commerce. I liked it at first, but now I’m not sure about it anymore… my first internship was in a shop…my idea of that was something else…” (Elle, age: 16, study field: Trade and Commerce, 1st year; at risk of dropping out, as identified by teachers).

In connection to this, some staff members (5) at vocational schools have observed that there are students who may face pressure from their parents to select a particular major. This can lead to difficulties and obstacles in their studies or even to dropping out if the student is not genuinely interested in the subject and has chosen it based solely on their parents’ wishes. According to SDT, a lack of autonomy causes a person to feel pressured and experience conflict, such as feeling pushed in an unwanted direction. Therefore, if the interviews reveal that students may be pressured by their parents to choose a specific major, it may indicate that these students’ need for autonomy is being suppressed.

“… many young people come to interviews with their parents who dominate the conversation. Even when I try to engage with the student directly, the parent often answers for them. This lack of autonomy can lead to problems later on, such as when a student is pressured to study a particular specialty chosen by their parents rather than of their own interests.” (Sergey, teacher-project manager).

It is possible that a student’s decision to drop out or stay in the vocational school is affected by their family’s cultural background. For example, in Estonia, there are students of Russian nationality who may feel pressured by their parents or grandparents to complete vocational school, even if they are not studying the desired specialty.

“In our vocational school we have experienced that if a student has a Russian cultural background, he will finish… pressure from the family relatives is great. In Estonian families, this pressure seems to be lower and students tend to drop out more easily.” (Anu, teacher).

Lack of autonomy occurs when vocational school students are not provided with sufficient freedom to make choices in their learning and major selection. If they perceive that their decisions are disregarded, this may result in resentment and diminished motivation to graduate from vocational school. The interview results may further confirm this notion, as a significant number of participating students admitted that their choice of major was not a decision of their own. Instead, it often came from outside influences, such as parental or friends’ suggestions.

The interviews revealed that education is important for gaining self-confidence and achieving social status. Although one student did not see a diploma as significant, she acknowledged societal pressure to obtain an education for success and advancement.

” It would be nice to continue studying, for example at a university. Actually, this education diploma is not that important to me, it’s more required in society that you should….” (Anna, age:19, study field: IT specialist, 1st year; has experienced several dropouts).

Education is important for developing critical thinking skills. However, some students reported that society puts too much emphasis on equating success with educational qualifications. Another concern was the challenges many of the students face to be successful with study requirements.

2. Students’ Learning Challenges and Participation in the Classes

Although autonomy is considered an important factor in promoting motivation, it is important to maintain a balance. Too much autonomy, especially in certain situations, can have unintended consequences, such as decreased motivation or the perception that learning is not taking place. An illustrative example of this can be drawn from the COVID-19 period when students were required to study from home. The COVID-19 pandemic presented challenges for vocational students, especially those prone to dropping out due to the shift to online learning. This was acknowledged as a major obstacle by both students and IVET staff in interviews. Challenges and fears affected students’ regular attendance, leading some to avoid school. Contrary to providing a solution, distance learning during the pandemic intensified these issues, as was revealed in the interviews.

”I had to check the study information system every day, but I usually slept in the mornings…at home I get lazier and then I don’t have the motivation” (Heli, age: 19, study field: Construction, 2nd year; has experienced several dropouts).

The interviews conducted with students suggest that many of them face challenges in staying interested in and comprehending the material they learn. Despite the importance of reading and comprehension skills for success in today’s information-driven society, most students consider books as a form of entertainment rather than a means for self-improvement and learning. This shift in attitude towards reading could pose a challenge to their academic and personal growth. They tend to be more interested in books related to fantasy, science fiction, crime, and topics such as school bullying and violence.

“I like crime books… one book talked about a girl whose mother was a serial killer. I never read compulsory school literature… The only book that was interesting to me was…about a youngster who ran away from home.” (Karen, age: 16, study field: IT specialist, 2nd year; at risk of dropping out, as identified by teachers).

“I don’t read books very much. There is a book “Class”. It was about bullying at school and there was a shooting in school.” (Kai, age:20, study field: hairdressing, 2nd year; has experienced a drop out).

Students in vocational school who are drawn to books centred on school bullying, violence, and science fiction may carry deeper emotional and psychological layers. Their reading preferences may likely reflect personal experiences or reflections on the darker aspects of society, suggesting potential complex social challenges they may face. In this context, signs of relatedness with SDT are noticeable, which may indicate social alienation, exclusion, and loneliness. Internships were also reported as being a source of difficulty by many of the students.

3. Challenges Regarding Internship

Students highlighted challenges with securing and completing internships, a mandatory component in vocational schools that may contribute to dropout rates. While students receive guidance on the content of practical training, finding a suitable contact is their responsibility. Many students gain their first work experience through internships, necessitating additional support from schools in securing placements. Students (6 out of 20) believe that such support should be provided to enhance their internship experience.

“The vocational school should help more in finding an internship placement. They very rarely recommend placement contacts, rather we look it up ourselves… I think for me it was more difficult to communicate…and during internship communicate with clients, it was difficult for me, I got nervous and I didn’t know how to respond when clients asked for help and, and…. I think that was the difficulty.” (Lorena, age: 20; study field: Business Management, 2nd year; at risk of dropping out, as identified by teachers).

“…students have to search for internships. We have internship bases that are not very good, rather at a low level, i.e. the student does not get much new knowledge or skills” (Katrin, teacher-specialist).

The challenges associated with practical experience are frequently mentioned as factors contributing to dropout rates. While internships can be challenging to secure, the study also revealed that students may experience feelings of insecurity when searching for internship opportunities. According to the SDT in the concept of the BPNS competence, it refers to a lack of competence because students lack self-confidence and belief in their own abilities. Similar to autonomy, supporting this need helps internalize external activities and leads to higher internal motivation.

Securing suitable placements for practical training posed a challenge for both students and staff in vocational schools. Existing training bases were perceived as offering limited opportunities for learning. Vocational school staff observed that students are sometimes offered jobs during internships, motivating them more than continuing their studies. This dynamic may contribute to students dropping out of school in favour of employment, presenting challenges to their educational and professional development.

“…during internships they get work experience and they also start to get a salary, and they realize that there is no point in finishing a profession in school…they choose instead of studying to go for a real job.” (Anne, teacher).

IVET staff suggest that combining work and study, particularly during internships, may contribute to vocational school dropout rates. Students face pressure from job offers during internships, leading to overwhelming work-study balance and a loss of motivation for vocational education. This set of concerns led to challenges with self-esteem and mental health.

4. Challenges Related to Self-esteem and Mental Health Problems

Students noted self-esteem and mental health challenges that vocational school teachers failed to acknowledge. They can reported being unsupported and alone, experienced anxiety disorders and other mental health problems that they reported not being taken seriously. Cases of teachers being rude or making inappropriate comments were reported, revealing a significant number of students with anxiety disorders in the study.

“I’m a bit socially anxious. I went to the school psychologist and told that I was having a hard time. I’m having a hard time all the time. It is difficult for me to ask for help.” (Anna, age:19, study field: IT Specialist, 1st year; she has experienced several dropouts).

Students noted that it was challenging for them to seek help and that they often reported feeling isolated in dealing with this issue while at school. There were also students who expressed difficulties already in their elementary school studies, pointing out reasons such as bullying, lack of teacher support, and overly stressful coursework. In the results of the interviews, signs related to SDT and mental health problems were identified. These mental health problems can often be linked to the feelings of loneliness and lack of social connections that characterize a lack of relatedness.

“I was bullied from the first grade…in the fourth grade I already went to a psychologist…my teacher labelled me as the worst boy in the class” (Mark, age: 21, study field: Construction, 3rd year; at risk of dropping out, as identified by teachers).

Bullying at school can damage students’ mental health, and reports suggest that teachers themselves may be the cause. 7 out of 20 students faced bullying from elementary school to vocational school, prompting frequent school changes without adequate support. This lack of help contributed to mental and physical health problems, including depression, anxiety and other psychiatric problems.

“In elementary school a teacher yelled at me constantly. She asked me to read a text, but I couldn’t read very well and she started yelling at me until I started to cry…” (Karen, age: 16, study field: IT Specialist, 2nd year; at risk of dropping out, as identified by teachers).

Bullying stress can negatively affect a student’s learning and motivation, while frequent school switches disrupt educational continuity. Hesitancy to disclose mental health issues due to stigma worsens the problem. The findings underscore the increasing prevalence of mental health problems among today’s youth. Like many other institutions, vocational schools may avoid admitting students with mental health disorders, who are also at risk of dropping out. Interviews revealed that schools often recommend these students to leave, as they lack support services such as a school psychologist. In addition, students may feel embarrassed to seek help from school psychologists.

“We had a psychologist at school, and I was suggested to go there, but I refused to go.

because she was my classmate’s stepmother.” (Karen, age: 16; study field: IT Specialist, 2nd year; at risk of dropping out, as identified by teachers).

Teachers and mentors should also be aware of students’ problems and provide support when needed, as demonstrated in the following case: “I wanted to leave the vocational school, I was so anxious. I didn’t go to school for two weeks, I was afraid to go there. Some teachers didn’t understand that, and I had a panic attack once.” (Elis, age: 20; study field: Hairdressing, 2nd year; at risk of dropping out, as identified by teachers). While teachers and staff may not mention mental health as a reason for student dropout, it is crucial to recognize that these issues are not always openly discussed or acknowledged, especially without an official diagnosis. Students may fear not being taken seriously or facing a stigma when seeking help, potentially leading to unaddressed mental health problems and contributing to dropout rates. Part of this might be also contributed to concerns about poor relationships with friends, classmates and teachers.

5. Poor Social Relations with Friends, Classmates and Teachers in Vocational School

A significant number of students (13 out of 20 students) preferred online communication through social media due to struggles with boredom, loneliness, anxiety, and depression, issues that staff and mentors in vocational schools did not address during interviews. While online contact may offer a sense of belonging and support, it can hinder the development of social skills and real-life relationships. This issue may be connected to the growing use of technology and social media among young people, impacting their social development and communication skills.

“I don’t want many friends, I rather want time to myself….my frustration is caused by teachers who treat us like little children, we always have to ask permission to do something e.g.…even to ask if I can go to throw trash away.” (Meelis, age:17; study field: IT Specialist, 1st year; at risk of dropping out, as identified by teachers).

There are various reasons why students may exhibit behavioural problems and withdraw from social interactions at school. For some, it may be a sign of underlying mental health issues such as anxiety or depression. Others may struggle with learning difficulties or feel overwhelmed by academic demands. In some cases, students may simply feel disconnected from their peers and find it difficult to form meaningful relationships. According to student reports, toxic friendships between students can affect academic performance and might lead to dropping out. Relatedly, there are signs that point to a lack of relatedness, such as students having behavioural problems and withdrawing from social interactions. Some may struggle with learning disabilities, seeking autonomy in dealing with their challenges. Feeling overwhelmed by academic demands can also be a manifestation of autonomy issues, as students may struggle with wanting more control over their academic responsibilities.

“I’ve never had friends. I don’t like to communicate…” (Sintia, age: 23, study field: Art, 2nd year; she has experienced a drop out).

Regardless of the underlying cause, it is important for educators and caregivers to be aware of the warning signs of behavioural problems and provide appropriate support and intervention. There are also signs of lack of relatedness in students’ stories. Students mentioned that they feel disconnected from their peers and struggle to form meaningful relationships. The COVID-19 pandemic, prompting a shift to online or hybrid learning, has impacted students’ social and emotional well-being. Vocational staff note challenges in social interaction, particularly for hands-on vocational programmes. Without in-person collaboration, students may feel isolated. Additionally, students in vocational programmes encounter barriers to social interaction amid the challenges of online learning.

“… when I have a class, they’re not very social. But if I still see one learner who feels very confident in this particular topic, I direct them to the other student who is maybe not so confident and say to them that they can do it together. But online it is impossible to socialize”. (Anne, teacher)

Poor social relations with teachers can pose a significant challenge for vocational school students, fostering feelings of frustration, disengagement, and a lack of motivation to learn. These challenges may signify a deficit in the relatedness (SDT), indicating a potential barrier to fulfilling meaningful connections in the educational environment and impacting students’ overall well-being and motivation.

“In my previous school the teachers were more interested in me, asked me how I was doing and supported me more.” (Kai, age:20; study field: Hairdressing, 2nd year; has experienced a drop out).

“Teachers in our vocational school should talk to us more and I wish they could talk to us more respectfully…sometimes they make unnecessary comments.” (Anna, age:19; study field: IT Specialist, 1st year; has experienced several dropouts).

It can be inferred that students desire more attention from their teachers. This suggests that the quality of teacher-student interactions, characterized by attention and positive engagement, may play a crucial role in shaping students’ learning experiences and motivation. The findings underscore the importance of strengthening communication and relationships between teachers and students to enhance overall well-being and academic success in vocational school. Yet, these challenges were also found within their relations with family members.

6. Challenges Related to the Student’s Poor Social Relationships in the Family

Vocational school teachers (5 out of 12) believe that students who face academic challenges also have issues at home. The lack of parental cooperation with vocational schools can be a significant barrier to student success. Parents play an important role in supporting their children’s education and providing a stable home environment that fosters academic achievement. These relationships might affect the student’s well-being and academic performance. Poor communication or conflict within the family can create stress, and anxiety for the student, which can make it difficult for them to concentrate and perform well in school.

“Family support is lacking as there are weak family systems in place…some parents do not wish to be involved and expect the vocational school to solely take care of the student” (Veera, teacher-specialist).

Interviews with school staff revealed that many parents do not want to cooperate with the vocational school. However, some parents may be reluctant to collaborate with vocational schools due to a variety of reasons, such as language barriers, cultural differences, or a lack of trust in the education system. This may point to the importance of addressing the challenges of parent collaboration to strengthen the school community’s sense of relatedness. According to students’ (14 out of 20) interviews, they do view their homes as a safe place where they can seek support from family members when needed. Although some students had single-parent households, parents working abroad, or said they were living alone, they reported feeling safe and having someone to turn to when needed. Even if they did not receive support from their parents, they could rely on siblings or grandparents for help.

“…The most important people in my life are my mother and father. The principled ones support me the most” (Meelis, age:17; study field: IT Specialist, 1st year; at risk of dropping out, as identified by teachers).

“Currently, my family holds great importance to me…My mother has been a mental support for me.” (Mark, age: 21; study field: Construction, 3rd year; at risk of dropping out, as identified by teachers).

Overall, the insights gathered from both school staff and students underscore the need for targeted efforts in addressing barriers to parent collaboration while also recognizing and reinforcing the supportive environments that students find within their homes.

7. Challenges in Combining Work and Study

Balancing work and school commitments can be a significant challenge for students in vocational schools, particularly for those who are completing internships or other work-based learning experiences. Students may struggle to manage their time effectively, which can lead to feelings of stress, burnout, and ultimately, dropping out of school. Schools could consider partnering with employers so that work-based learning experiences are structured in ways that support students’ academic success. This may include setting clear expectations for workload and communication, regular check-ins and feedback, and ensuring students have access to the resources they need to succeed both academically and professionally.

“They will immediately go into the real world of work and the employer proposes to them to work in shifts beside the school… I’ve had students who don’t make it to the first classes in the morning because they’ve finished work at three in the morning.” (Anu, teacher).

It is not uncommon for students in vocational schools, particularly boys, to seek employment opportunities outside of their studies. This may be due to a variety of factors, including a desire for financial independence and the need to support themselves and their families.

“We have noticed that mostly boys are looking for work besides the studies… in our statistics during the 3rd study year many students already want to live independently. They need money for everyday life” (Veera, teacher-specialist).

Financial difficulties and the challenge of working while studying can be major obstacles for students in initial vocational schools. These factors can put a significant strain on students’ time and resources, making it difficult to balance work and academic commitments. Based on the example of one student in the interviews, it is unfortunate that despite the course mentor’s efforts to help him, he could not cope with the work and educational requirements. This underscores the importance of providing students with comprehensive support services to help them manage their financial and academic responsibilities. Financial challenges and the need to work while studying can affect students’ autonomy. The need to balance work and academic responsibilities can limit students’ perceived control over their time and resources.

“I had financial problems. And I had to go to work beside study. My mentor…offered me to do my stuff in June…but I didn’t get there because at that moment I was working…and I finished so late and I didn’t have a chance to get there.” (Mark; age: 21, study field: Construction, 3rd year; at risk of dropping out, as identified by teachers).

However, early recruitment with attractive salaries can also lead to a decline in motivation to focus on studies, as students may prioritize earning money over their academic commitments. This, of course is now a growing concern with high levels of employment leading to a reduced requirement for young people to complete compulsory education and tertiary education programs. Another and related contemporary issue is the attraction of young people to electronic devices and computer gaming.

8. Challenges Related to Addiction to Smart Devices and Computer Games

The prevalence of smart devices and computer games has become a significant challenge for vocational school teachers. Students (13 out of 20 students) report spending significant amounts of time (up to 8–12 hours a day) on these devices, which can negatively impact their academic performance and overall wellbeing. In some cases, students may become addicted to smart devices and computer games, making it difficult for them to focus on their studies and engage in other activities. This can have a negative impact on their social skills, as well as their ability to manage their time and prioritize their responsibilities.

“I use social media a lot, when I’m bored I spend quite a lot of time on social media. At home I am usually online… I mostly watch Facebook, Instagram, Tik-Tok and YouTube videos.” (Ken, age: 19; study field: Landscape-gardening, 3rd year; at risk of dropping out, as identified by teachers).

“I really don’t use social media much, I’m more like playing online computer games. I could play for up to eight hours a day… I would rather be in a dark room than go outside” (Karen, age: 16, study field: IT Specialist, 2nd year; at risk of dropping out, as identified by teachers).

The challenges with student focus and communication skills in vocational schools can be attributed, in part, to the prevalence of technology and social media. According to teachers, students are constantly distracted by the vast amount of information available to them through their devices, which makes it difficult for them to focus on their studies and develop critical thinking skills. In addition to this, some teachers also believe that students lack the ability to effectively communicate in real-life situations. They may be comfortable communicating through digital devices, but struggle with face-to-face interactions. This can make it difficult for them to develop important social skills and build meaningful relationships with their peers and mentors. The negative impact on social skills highlighted by teachers may be related to students’ poor relatedness (SDT). In addition, excessive use of the smartphone can be a consequence of feelings of loneliness, as several young people in the study pointed out that they do not have friends and often feel lonely. Excessive use of smartphones and computer games can hinder students’ ability to engage socially, preventing their needs for relatedness from being met.

“Some students are very lonely, and they are afraid to communicate with others in school…but they are very good communicators on their smartphones or online” (Katrin, teacher-internship specialist).

The issue of smartphone and computer game addiction among vocational school students is a complex one. While many students deny having problems with addiction, vocational school teachers believe that it is a significant issue that can negatively impact academic performance and social skills. One potential reason for the discrepancy between student and teacher perspectives is that students may not be fully aware of the extent to which their device use is impacting their academic and social lives. They may also be in denial about the addictive nature of smartphones and computer games.

Factors Underpinning Low Retention within Vocational Education

The following discussion highlights the various challenges that students face in vocational school, which are interpreted by using the SDT and the conceptual frame of BPNS. The challenges for vocational school students were dissatisfaction with the chosen profession, difficulties in finding an internship, studying, attending classes and the attitude of teachers at school towards them. They admitted that they lack motivation to study the field. Motivation, whether intrinsic or extrinsic, is a crucial determinant of success and failure (Ryan & Deci, 2017). The findings of other studies (Meyers & Houssemand, 2011) highlighting a lack of motivation as a cause for dropping out of school align with the conclusions drawn from this study. It was observed that this lack of motivation might be attributed more to the fact that the choice of the field of study was influenced by parental preferences rather than the student’s own. Additionally, students may have lacked a realistic perception of their chosen field’s practical application in a real workplace. These results underscore the importance of enhancing students’ self-determination in the process of choosing a field of study and ensuring that educational programmes clearly depict the practical relevance of a chosen field in the actual job market.

Various studies (Meyers & Houssemand, 2011) on school dropout have identified issues related to internships as common causes for dropping out. Also, in this study students and school staff pointed out that finding an internship place can be challenging and also could be one of the reasons why students drop out of vocational school. While internships can be challenging to secure, the study also revealed that students may experience feelings of insecurity when searching for internship opportunities. According to the SDT in the concept of BPNS competence, it refers to a lack of competence because students lack self-confidence and belief in their own abilities. Similarly, to autonomy (Ryan & Deci, 2017), supporting this need helps internalize external activities and leads to higher internal motivation.

In addition, the study revealed significant signs of mental health problems among young people. Although the students themselves did not admit it in the interviews, they pointed out that they often experience depression, isolation, anxiety, low self-confidence and suffer from traumas caused by previous school bullying. Consequently, it can be inferred that the students’ basic psychological needs are not being satisfied. This inference is drawn from the observed characteristics, as connections may be identified with autonomy, competence, and relatedness within the framework of basic psychological needs (Ryan & Deci, 2017). If these needs are not met, it can lead to decreased motivation and mental health problems. (Vansteenkiste et al., 2020; Ryan & Deci, 2017; Vansteenkiste & Ryan, 2013) Balancing and satisfying these needs is crucial. Supporting students in decision-making and fostering involvement can address autonomy challenges and potentially boost motivation to study. It is important for vocational schools to create a supportive and inclusive environment that prioritizes mental health and provides opportunities for students to seek help when needed.

In other research findings (Korumaz & Ekşioğlu, 2022), it has also been emphasized that vocational schools and teachers play a crucial role in supporting students, even when progress is slow. Teachers should exhibit greater tolerance and understanding towards the youth. The importance of family support for young individuals is underscored. Thoughts from this study also highlight the idea that schools and students’ families should collaborate more closely to provide support for the students’ learning.

The results of the study showed that, at times, the perceptions of vocational school students differed significantly from those of the school staff. Specifically, students had different views than the school staff on certain topics. These differences were most notable in areas related to mental health challenges, poor social relationships with friends, classmates, and teachers, as well as addiction to smart devices and computer games.

The published views were consistent with the findings in the scientific literature (Meyers & Houssemand, 2011; Battin-Pearson & Newcomb, 2000), but additionally, new factors emerged that may influence dropout from vocational school, such as students’ mental health problems.

Limitations, Implications, Future Directions and Conclusion

This study provided an opportunity to elucidate the challenges faced by vocational school students that may influence dropout rates. These challenges included motivational issues, practice difficulties and mental health issues. The contribution of this article lies in its potential to understand the perspectives of different parties. Therefore, this study made it possible to explore different perspectives, considering the perspectives of both students and vocational school teachers. In addition, the results of this study highlight the need for targeted interventions that address the challenges identified among vocational school students. The findings underscore the importance of addressing these challenges for student retention and success, with particular emphasis on the significance of considering students’ mental health in intervention strategies. In addition, the study highlighted the need for a supportive and inclusive environment, cooperation between schools and families, and a focus on the mental well-being of students.

While the insights gleaned from this study are valuable, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of the sample size. The article’s limitations may stem from various factors, such as the small research sample (students n = 20 and teachers n = 12), therefore the results may not be representative of the entire population of students and teachers in vocational schools. Thus, the results should be interpreted with caution, and further studies with larger and more diverse samples are warranted to confirm and build on the findings of this study. Acknowledging the limitations of the research design may further enhance the validity and generalizability of future research in this area, thereby contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of the challenges and opportunities of vocational education. Implications of this study highlight challenges that vocational school students face, particularly those that may contribute to dropout rates. These study results show the need for targeted support mechanisms. Policymakers and education stakeholders can use this knowledge to design and implement initiatives that aim to improve the overall experience of students in vocational schools.

For future research, it would be beneficial to broaden the study’s scope to include neighboring countries, allowing for diverse perspectives from varied contexts to be explored. Additionally, efforts should be undertaken to ensure gender balance among participants, aiming for an equal or similar proportion of both boys and girls. In addition to individual interviews and focus group discussions, this study could be enhanced by incorporating additional research methods to deepen its scope and breadth. Surveys administered to a wider sample of vocational school students and teachers could complement the qualitative insights gained from interviews by providing quantitative data to corroborate and expand upon the findings. Furthermore, expert interviews with educational policymakers, specialists in the field, and vocational school administrators could provide broader perspectives on systemic issues and potential solutions.

Notes

Empower VET Baltic Research Programme Project “Vocational Education and Workplace Training Enhancing Social Inclusion of At-Risk Young People”.

References

Battin-Pearson, S., & Newcomb, M. D. (2000). Predictors of early high school dropout: A test of five theories. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92, 568–582.

Böhn, S., & Deutscher, V. (2022). Dropout from initial vocational training –A meta-synthesis of reasons from the apprentice’s point of view. Educational Research Review. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100414. ,35.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology.

Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

Cedefop (2016). Leaving education early: Putting vocational education and training centre stage. Volume I: Investigating causes and extent. Publications Office of the European Union.

Espenberg, K., Beilmann, M., Rahnu, M., Reincke, E., & Themas, E. (2012). Õpingute katkestamise põhjused kutseõppes (pp. 26–34). Tartu: Tartu ülikool. https://www.hm.ee/sites/default/files/opingute_katkestamise_pohjused_kutseoppes.pdf.

Eurostat Statistics (2022). [https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Early_leavers_from_education_and_training].

Eurostat (2021). Early leavers from education and training by sex and age, and by level of education and training (ISCED-F 2013) - annual data. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/educ_uoe_enra21/default/table?lang=en.

Evans, G. W., Li, D., & Whipple, S. S. (2010). Cumulative risk and child development. Psychological Bulletin, 136(6), 793–819.

Evans, K., Waite, E., Kerch, N. (2014). Towards a social ecology of adult learning in and through the workplace. In M. Malloch, L. Cairns, K. Evans, & B. O´Connor (Eds.), The sage handbook of workplace learning

Haaristo, H-S., & Kirss, L. (2018). Kutseõppeasutuste tugisüsteemide analüüs: olukorra kaardistus, võimalused ja väljakutsed tugisüsteemide rakendamisel katkestamise ennetusmeetmena, Poliitikauuringute Keskus Praxis. http://www.praxis.ee/wpcontent/uploads/2017/05/Kutsehariduse-tugisüsteemid_aruanne_lõplik.pdf.

HTM (2020). Haridus-ja teadusministeeriumi 2019. aasta tulemusaruanne. Tartu: HTM

Jaggo, I. (2019). Ülevaade kutsehariduse katkestamisest 2005–2017. Haridus- ja Teadusministeerium.

Jeno, L. M., Egelandsdal, K., & Grytnes, J-A. (2022). A qualitative investigation of psychological need-satisfying experiences of a mobile learning application: A self-determination theory approach. Computers and Education Open, 3, 100108.

Korumaz, M., & Ekşioğlu, E. (2022). Why do students in vocational and technical education drop out? A qualitative case study. International Journal of Contemporary Educational Research, 9(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.33200/ijcer.935042.

Krötz, M., & Deutscher, V. (2022). Drop-out in dual VET: Why we should consider the drop-out direction when analyzing drop-out. Empirical Res Voc Ed Train, 14, 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40461-021-00127-x.

Lareau, A. (2003). Unequal childhoods: Race, class, and family life. University of California Press.

Le Boutillier, C., & Croucher, A. (2010). Social inclusion and mental health. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(3), 136–139. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802210X12682330090578

Lörinc, M., Ryan, L., D’Angelo, A., Kaye, N. (2020). De-individualising the ‘NEET problem’: An ecological systems analysis. European Educational Research Journal, 19(5), 412–427

Novosel, L., Deshler, D. D., Pollitt, D. T., Mark, C., & Mitchell, B. B. (2012). At-Risk learners. In N. M. Seel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of the sciences of Learning. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1428-6_551.

Praxis. (2013). Noored ja sotsiaalne kaasatus. Noorteseire aastaraamat 2012. Tallinn: Praxis

Raymond, M., & Houssemand, C. (2011). Teachers’ perception of school drop-out in Luxembourg. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 15 (2011) 1514–1517.

Reiska, E. (2018). Noorte sotsiaalne tõrjutus. RASI toimetised nr 3. Tallinn: Tallinna Ülikool

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). Overview of self-determination theory. Handbook of self-determination research. University of Rochester.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York, NY: Guilford Publishing

Schmid, E., & Garrels, E. (2022). Editorial: Inclusion in vocational education and training (VET). Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE), 6(3–4). https://doi.org/10.7577/njcie.5073.

Serbak, K. (2018). Mis mõjutab Keskhariduseni jõudmist Eestis? Analüüs EHISe andmetel. Haridus- ja Teadusministeerium.

Vansteenkiste, M., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration.

Vansteenkiste, M., & Van den Broeck, A. (2015). Understanding the Motivational Dynamics Among Unemployed Individuals: Refreshing Insights from the Self-Determination Theory Perspective Maarten Vansteenkiste and Anja Van den Broeck The Oxford Handbook of Job Loss and Job Search (Forthcoming) Edited by Ute-Christine Klehe and Edwin A.J. van Hooft. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.3299.9122.

Vansteenkiste, M., Ryan, R. M., & Soenens, B. (2020). Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions.Motivation and Emotion 44:1–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09818-1.

Weaver-Hightower, M. B. (2008). An ecology metaphor for educational policy analysis: A call to complexity. Educational Researcher, 37(3), 153–167

Wilson, M. V. S. (2014). Basic psychological need satisfaction from the perspective of permanently excluded children and young people: An exploratory study. University of London. School of Psychology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing of Interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bentsalo, I., Loogma, K., Ümarik, M. et al. Challenges and Risk Factors of Early Leaving from IVET: Perceptions of Students and Schools´ Staff. Vocations and Learning 17, 351–371 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-024-09345-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-024-09345-2