Abstract

This article is based on research about upper secondary students' experiences in vocational becoming as they develop conceptualized knowing through interactions with others. Interactions for meaning-making by vocationalising concepts also involve feedback relating to occupation-specific tasks. The aim was to understand this constructivist process of occupational identity formation - a goal of vocational education. The research reported here draws on data from participant observations and focus group interviews with 34 students in 2nd and 3rd grades in two schools, who were training to become security officers. Students vocationalise five features of security practices: (i) transforming anomaly into specialized concept; (ii) the uniform as a marker; (iii) accountability to the security industry through zero limit; (iv) modernizing the security occupation; and (v) social, study and professional conduct. The findings indicate that processual feedback supports the development of vocational conceptual knowing inferentially in the space of reasons. Teacher-led processual feedback provides more opportunities for vocationalising concepts, whereas student-led feedback during group work offers fewer such opportunities, although it does strengthen student identity. Overall, the findings show that collective meaning-making, supported by processual feedback, contributes to the construction of specialized knowledge for vocational becoming, thus leading to emergent vocational identity. However, making firm decisions about a chosen vocation takes time, and this appears challenging especially for youth with their limited life experiences (Tanggaard in Journal of Education and Work, 20(5), 453–466, 2007). For many prospective security officers, their vantage point remains uncertain, as they imagine, deliberate and put expectations to a reality check during the course of their study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

When preparing for an occupation through vocational education and training (VET), students are introduced to a range of unfamiliar vocational concepts with which they are expected to be conversant. Grasping vocational concepts entails appropriating meanings of words and what they implicitly mean in specific work settings (Brandom 2000). It is a deliberate social act - some spontaneous and others acquired through conscious efforts of instruction and education. Everyday concepts (spontannyje poniatja) emerge from rich, sensory practice of living in physical and social contexts that are natural and somewhat “unruly”, and unmethodical (Vygotskij 1934). Development of everyday concepts commences with embryonic forms of structure and inferences, followed by rudimentary generalization of meanings that arise through everyday experiences. So, grasping a concept is about conceptualising it within a net of socially-constructed and agreed inferences that are vocation specific. We label this as a process of vocationalising concepts. We propose that the process of vocationalising concepts metaphorically forms entry points into a chosen vocation (Chan 2013). It helps students integrate their classroom experiences (Billett 2014) with demands of the vocation. Common vocational concepts that students encounter in VET materialize through a system of mediated meaning-making followed by degrees of generalizations in different physical and social contexts (e.g. workplaces) - influenced by the zone of proximity and active social interactions.

While generalized vocational concepts form the foundational basis for grasping of meanings, specialized vocational concepts need to be framed within the concreteness of a reference point, such as a specific work settings that forms the physical context of social meaning-making. For students, specialized vocational concepts may gradually transform into everyday “living” concepts when saturated with empirical meanings that resonate with students’ experiences in vocational education and training. Specialized concepts gained through VET in schools and workplace settings help realise vocational knowing and becoming. However, students alone cannot fully realize inferential meaning-making without input and feedback from teachers, peers and experienced workers, for instance. So, the question here is how students vocationalise specialized concepts, and how feedback from teachers and peers contribute to their grasping of specialized vocational concepts. This was the focus of research reported in this article. In many ways, it addresses the distinction that Vygotskij made about differences between everyday and scientific conceptions of knowledge.

In this article we illuminate young people’s vocational becoming conceptualized as a constructivist process of vocationalising concepts, facilitated through feedback from peers and teachers. We report research about the development of specialized vocational knowing by Swedish students completing school-based upper secondary vocational education and training (USVET). The case presented here involves students preparing to become security officers. The point of departure is a VET curriculum that is almost entirely set in classroom settings. That is, the program is considered to be limited (i.e. minimum of 15 weeks over a period of three years) in contact with authentic workplace settings. The case study investigated how trainee security officers unpacked and appropriated concepts specific to this vocation; how they constructed meanings through interactions during feedback sessions; and how they learned to develop their capacity to act in accordance with the norms and traditions of security work. The study was guided by two research questions: i) What concepts do students vocationalise?; and ii) What are the contributions of feedback in vocationalising concepts for specialized vocational knowing?

The article commences with theoretical interpretations about the development of vocational concepts and the significance of feedback. This is followed by a brief overview of the Swedish upper secondary school curriculum for training security officers. Then, the research method and our approach to data analysis are explained. Next, the findings are presented, followed by a discussion. Finally, a set of conclusions are drawn. The analyses validate the significance of supportive physical and social spaces that form a communal space of reasons for meaning-making, thereby accomplishing entry points into a chosen vocation. Vocational concepts are developed inferentially and this is augmented with feedback from teachers, peers and other experienced persons. The findings show that teacher-led feedback sessions increase opportunities for vocationalising concepts, but require a shared space of reasons. Student-led sessions on the other hand tend to focus more on strengthening studentship - less on vocationalising concepts.

Developing Vocational Concepts through Feedback

Grasping vocational concepts is about grasping the use of certain words and what they denote. It involves deducting, justifying, giving and asking for meanings and their appropriation (Brandom 2000). The theoretical framework advanced here builds on Vygotskij’s (1934) ideas about concept development, and inferential meaning-making in a shared space of reasons (Brandom 2000; Derry 2008). Derry (2008) explains that students are initiated into a social space within which they will be able to participate in a practice of giving and asking for reasons. A space of reasons enables them to locate things in a pattern or a grid for action. However, this space needs to be open and inviting for students to freely, deliberately and consciously relate to occupational demands and make judgement on a course of action. Bijlsma et al. (2016) contend that vocational becoming through knowledge construction is a reciprocal process of socializing and personalizing. Socializing knowledge requires students to interpret vocational knowledge by explicating and clarifying concepts, values and beliefs with “relevant others” (p. 380) in the workplace and in classroom settings. Implicitly, socializing the concepts or meaning-making is about tapping into and contributing to a collective body of knowledge. It requires one to be well aligned with the community in particular practice settings (Colley et al. 2003; Vincent and Braun 2011). Personalizing or sense making, on the other hand, focuses on individual experiences. Thus, students make sense by concretising, justifying and testing ideas (Heusdens et al. 2016) within a shared learning space.

Concept development through inferential meaning-making in sharing a space of reasons captures the interface between theoretical understandings about vocational concepts and generalization of specialized concepts. These transpire from individuals’ living experiences in the context of work. Knowledge conceptualized through the tripartite interactions (i.e. between individual learners, peers and teachers) involves constant cycles of concretising and conceptualizing vocational concepts (Heusdens et al. 2016). This enables students to relate to occupational demands, make judgement and enact a course of action. They are presented with opportunities to create coherence through interwoven and subjectively meaningful patterns of participation (Tanggaard 2007; Brockmann 2010) in various social practices (Lave and Wenger 1991). For example, students studying to become security officers needs to grasp the concept of a uniform. This comprises knowing ways to accomplish the wearing of uniform, the proper ways of storing the equipment in the belt, and also ominous consequences of not being appropriately uniformed. These understandings emerge from space of reasons characteristic of the occupation. As such, a space of reasons also offers a normative context for what to expect. However, Sandal et al. (2014) caution that students do not always appreciate that vocational knowledge entails the appropriation of theoretical, everyday and common-sense knowledge.

The accounts above substantiate that vocationalising concepts through inferential meaning-making with others is a multifaceted activity that can be challenging for VET students because they are yet to be fully initiated into the everydayness of work that shapes occupations. Correspondingly, the accomplishment of vocationalised concepts demands methodical curriculum provisions, not just understandings gained from everyday “unruly” circumstances. Importantly, pedagogical interventions that enrich engagement with others (e.g. teachers, peers and more experienced others) augment collaborative inferences. Feedback from others, for instance, enhances inferential meaning-making to correctly interpret and take actions (Merry et al. 2013). Thus, feedback is interpreted here as going beyond how well tasks are performed. That is, students’ “understanding of the underlying ‘how’ or ‘why’ associated with tasks or processes” (Cornell 2017, p. 279) embedded in the socio-cultural context of practice settings are emphasised. In this way, feedback becomes an important mediator for the development of specialised vocational concepts and knowing. Guile (2006) maintains that constructive feedback to support vocational formation requires not only an appropriate space of reasons, but also a common medium for communicating meanings to acquire rich vocational literacy, because concepts are used to ‘act and communicate inferentially’ (p.265). This allows individuals to respond ‘differentially to actions, events and thoughts’ (p. 265).

The commentary above informs the theoretical foundations for our research. It summarises the process of vocationalising concepts and how feedback contributes to attaining specialised vocational knowing. Our interest here is in not just concepts that develop spontaneously, but those concepts that are purposefully elaborated in interaction-rich classroom situations for development of the students’ specialized vocational knowing (Vygotskij 1934), which contribute to vocational becoming (Billett 2011) through VET. The next section provides an overview of the USVET program for trainee security officers in our case study.

Pathways into the Security Officer Occupation

Upper secondary education in Sweden consists of three-year programs steered towards specific diploma goals. Training to become a security officer is formally placed within the Child and Recreation Program, one of 12 national vocational programs. This program primarily prepares students for people-centred occupations: work with children, youth and adults in various settings (SNAE 2011).

Students in upper secondary school can gain accreditation as security officers through a program offered in collaboration with the security industry, represented by the Security Industry and Working Environment Committee (henceforth BYA),Footnote 1 which is responsible for a specific training package, including its syllabus, instructors, instruction and assessment. The training package consists of two courses and 160 h of workplace-based learning with a security company. The syllabus for a subject called Fire, Surveillance and Safety is equivalent to the training package for the security industry. In addition, another course called the Diploma project requires students to demonstrate their preparedness for outcomes stipulated for the security officer vocation (SNAE 2011). That is, they need to show competence in carrying out tasks in the vocational area. Aside from a set of broad generic goals (e.g., relating to competencies in planning and communication), there is no specific syllabus for the Diploma project. This allows teachers flexibility in designing the course to align with specific demands of frequently recurrent work tasks. In short, the program that offers training to become a security officer is human-centred (Virtanen et al. 2008) and stresses pedagogical work and leadership in various occupational settings.

While there has been steady growth in the security industry in the Western world (Manzo 2012), training to become a security officer remains rudimentary and fragmentary at best (Diphoorn 2016). In Sweden for instance, security officers (mostly males) were hired on their personal dispositions such as good reputation, sobriety, responsibility and self-discipline, good health and stamina. However, following public demand there is now greater standardization and regulation of services through training and accreditation. When first introduced, the training curriculum comprised fire protection, personal demeanor, attitude towards the public and the roles and responsibilities of security officers. Security officers are now required to be accredited through vocational training. The curriculum for vocational training is regulated by the National Police Authority (RPSFS 2012:18). There are other educational pathways into the occupation, predominantly targeting adults where the costs of training are covered by an accredited security company, or where students self-finance or seek assistance from certain national state offices. The study reported in this article was based on the pathway offered through the training program in upper secondary schools.

The Study

For the purpose of this study, two courses from the training package overseen by BYA were selected (School A), together with a course labelled as a Diploma project (School B). The latter had an explicit goal of developing a security and safety plan for a public event such as an international fair. Both the training package and the Diploma project aim explicitly at helping students develop vocational competence as well as identity as security officers, though in slightly different ways.

In School A, seven instructors (BYA staff and practitioners from the security industry) came one at a time to deliver the training package. In School B, students worked independently on the Diploma project in three mixed-grade groups (2nd and 3rd grade, i.e. USVET students in second and third year of their study program) facilitated by one, or occasionally two, teachers. Students in the second or third year of study gained a broad range of experiences, hence were better placed to advance their vocational identity formation, compared to students in 1st grade (those in the first year of their study program). There is no intention here to compare the training package trajectory with the Diploma project on the basis of curricular or learning designs, since they are different on several accounts.

Sample

A total of 10 students and seven instructors from School A, and 24 students and two teachers from School B participated in this study. The ethics rules that pertain to humanistic and social science research were observed (Vetenskapsrådet [Research Council] 2017). The students were invited to participate voluntarily, and written consent was obtained prior to data collection. The two teachers were invited and verbal consent was obtained. School A provided a purposeful sample selected on the advice of the Security Industry and Working Environment Committee, claiming School A to be an example showing successful collaboration between the security industry and the school. The choice of School B was based on convenience of access, as it was close to the university and had recently implemented a new, hence interesting, learning design (mixed-grade group work) for the Diploma project.

Method

Data were collected from participant observations (approximately 90 h in total) and five focus group interviews involving 22 students. These two sources complemented each other, allowing the focus group interviews to obtain access to collective accounts of students´ experiences. The students were observed in classrooms between February and May in 2016.Footnote 2 The purpose of the observations was to record what learning opportunities were afforded in the training package as well as in the Diploma project, and to record verbal and non-verbal interactions. The researcher (first author) sat close to the students, directing her attention to watching, listening and later seeking clarifications about what she had observed, rather than applying a specific protocol for the observations. Whenever a practical opportunity arose, segments of lessons were recorded as examples of activities that involved interactions between and among students and teachers, the study materials, and other artefacts. The focus of observations was on the students’ interaction with others, supported by learning materials and design. These interactions were recorded as field notes. The interviews followed once all observations were complete. Prompts for the focus group interviews, lasting approximately one hour, were derived from the analyses of observation and field notes, and loosely guided by a large mind-map. Probing questions were asked to allow for student directed conversations about their experiences (Thomsson 2010). The interviews and lesson segments were digitally recorded, transcribed and de-identified (Delamont 2008; Gibbs 2012). These, together with recorded segments of lessons and field notes, comprised rich empirical data. The participants´ anonymity and confidentiality were assured by de-identifying the transcripts and by following ethics protocols stipulated by the Research Council.

Analysis of Data

Three steps guided the analytical procedure to code typical excerpts. The first step involved data-driven content analysis that yielded broad emergent themes and sub-themes on assessment of vocational knowing (theme) and its aspects (i.e., constructive alignment as a sub-theme). The themes and sub-themes reflected students’ experiences of engagement and interaction with the learning curriculum, peers, teachers and instructors. Recurrent words and phrases were viewed in the context of the situations in which they occurred during the instruction. The words and issues were brought to attention by writing them on the whiteboard and pointing, illustrating through anecdotes, role-playing, demonstrating and rehearsing using various memory enhancing techniques, such as abbreviations, checklists, bullet points and acronyms. The issues thus highlighted by the teachers and instructors were deemed as particularly important from the point of view of specialized vocational knowing. For each theme interaction-rich sequences were identified and used in the second step of analysis. Hence the second step was explorative, exercising careful judgement in order to study closely how certain words gained meanings that surpassed the commonsensical interpretations from a layman’s point of view. Moreover, the second step was about tracking the process of vocational enrichment of certain words that led to the extraction of several vocationally relevant concepts. The third step was to discern general patterns of feedback exchanges, as the students reconciled their prior knowledge and understanding with new understandings resulting from collective reasoning, ending in inferential meaning-making.

Findings: Vocationalising Concepts

Content analysis of the data identified five sets of concepts vocationalised by would-be security officers. These were: (i) transforming anomaly into specialized concept; (ii) the uniform as a marker; (iii) accountability to the security industry through zero limit; (iv) modernizing the security occupation; and (v) social, study and professional conduct. These are summarized in Table 1. The first column lists the key concepts, the second summarizes the rationale, third column lists related actions, and the last column states the significance for identity formation.

Each of the concepts is elaborated below.

-

i)

Transforming anomaly into specialized concept

An important aspect of becoming a security officer through the upper secondary school curriculum entails correct interpretation or summarization of key words and phrases used in specific or general situations. Condensation is enacted collectively during interactions, reinforced with feedback for deeper understanding. For instance, at School A, Fredrik, the instructor, invited the 3rd graders to un-pack and re-pack the meanings of the word anomaly (avvikelse) to vocationalise this concept. An anomaly is an unexpected state or event that could potentially cause danger (Bevakningsbranschens yrkes- och arbetsmiljönämnd Väktarskolan 2015). The routine part of security duties includes making rounds to detect various kinds of anomalies. Correct identification of an anomaly and executing appropriate measures are the first steps in preventing incidences and protecting people and property. An open door or window detected during a round is an anomaly which all the 3rd graders had experienced many times during their work placement. The instructor enriches that experience with meanings beyond the personal and sensory, as well as common sense knowledge (Sandal et al. 2014). Fredrik (the instructor) talks about different “filters” a security officer needs to employ to understand what is going on as he directs the students: “Do not always anticipate crime; change filters, it’s crime protection”. He encourages the students to see an anomaly through different filters in order to decide what action is required. He acknowledges that students will have to explicitly classify an anomaly they detect in one of four forms - observation, defect, threatening incidence and (just) incidence - as well as particular categories i.e., crime protection, fire protection, facility protection or accident protection. Then the students decide what action to take. This type of propositional knowledge is necessary for students to pass the written test and qualify as security officers. In time though, students transform their conceptualization of an anomaly as a tool for action, scaling down and modifying their procedures.

In this instance, the students are invited by Fredrik to occupy a space of reasons to understand inferentially, what an anomaly means to them. Having already gained some familiarity with the work of security officers, they are eager to learn more concrete and generalized meanings. Thus, an anomaly in the space of reasons enables students to collectively draw inferences. Fredrik’s feedback reinforces, interrogates and encourages the students to give and ask for reasons. They are asked to justify ways to detect anomalies, analyse and summarise, to make sense by connecting anomalies, then employ appropriate responses. There is a constant movement between the concrete, the localized and the general that contributes to meaning condensation. When the instructor asks the students whether they used a method called SKÖLL (general, conceptual) they recast their answers in concrete, localized terms:

Fredrik: Did you detect anomalies by smell?

Dennis: There was a smell of smoke in there and then we detected some people there.

Fredrik: Every time you enter you have to stop, was it difficult to use SKÖLL (use senses to detect) Footnote 3 ?

Robert: There was a security officer who used to wear bare arms deliberately to feel air currents. [observation, School A, grade 3, March 2016]

The feedback and discussions generated movement between conceptualizing, stripping the knowledge bare of personalized details, and concretising - that is, saturating it with the particular (Bijlsma et al. 2016; Heusdens et al. 2016). This is how the meaning of anomaly as a concept is vocationalised through feedback on the process, exhorting students to apply a security officer lens to see anomalies. The students discern both the particular and the “abstract” as security officer specific, far from dichotomizing it into theory and practice - all based on integration of sensory experiences with processual feedback.

Appropriate vocationalisation of anomalies for security occupations contributes to the development of vocational knowing. Another concept relates to the uniform as a marker for security officers.

-

ii)

The uniform as a marker

Students’ interpretation of the security officer uniform was laden with meaning. For them, the uniform legitimates ways of exercising force in order to restrain violence, and gives freedom of movement. They fixed the meaning of uniform as a protective measure, where the wearer remains anonymous although sometimes contradictory, since it could also jeopardize one’s personal security, given it exposes the wearer and also makes him/her vulnerable. An interpretation is that this contradiction presents a conceptual entry point. It is not just about putting on a uniform like wearing any other clothing, but also ways of “accomplishing” the uniform as a transformational artefact that morphs the wearer from a member of the public into a worker who performs a particular role. Being a security officer, in turn, granted and guaranteed the wearer extended legal protection and power. Knowing how to “accomplish” the uniform was interpreted as legitimate knowledge. Incomplete accoutrement may strip a security officer of rights to specific extended legal protection. The 3rd-graders inferred this in the space of reasons they collectively inhabited. The verbal feedback they provided to each other helped them collectively condense the concept of uniform with vocationally relevant meaning, related to a security officer’s all-encompassing need for self-protection. Peer feedback directed everyone’s attention to a collectively established appreciation of this need. This is exemplified in the conversation below.

Marie: Everything must be black

Annika: The uniform

Stina: Black or else dark gray, isn’t it?

All: Yeah

Stina: Are you wearing white socks? Then you are not approved, you aren’t a real security officer

Annika: Mm, but what about if you can’t see them?

Stina: You mustn’t, “what socks did you put on? Well, they were white”. Then you were not a real security officer…

Annika: That’s true

Stina: If I’m knocked down as a security officer, wearing white socks then it won’t count as an offence to an officer simply because I was wearing white socks as opposed to black

Annika: They can blame you for that

Stina: Because I haven’t fulfilled it …

Annika: The uniform

Stina: The uniform. [focus group, School B, grade 3, May 2016]

The students saturate the uniform with factual, judicial meaning (it won’t count as an offence) in addition to emotional and moral meanings. They move between the particular and the general threat-protection contradiction. For Ellen, the sheer sight of the uniform calls upon certain actions the students learn through feedback and apply in order to handle threats and abuse.

Ellen: … There was that guy passing by, asking my colleagues first “What the hell are you standing here for?” They said “take it easy, it’s the way we do it”. Then he placed himself right in front of me, just a couple of inches away from my face and said “Yeah, you’ve got here a pretty girl with pretty eyes”. I felt really offended (with emphasis) since he was standing that close so I had to retreat behind my colleague. It was scary (laughs). [focus group, School A, grade 3, April 2016]

The episode above shows the perpetrator was provoked by the sheer presence of a uniform. His verbal and non-verbal response bring about a chain of reactions, getting the student to retreat to safety behind a colleague. The incident above triggered an interaction between Ellen, her supervisors, and the perpetrator. It exemplifies how a particular emotional value saturates the concept of uniform as a general contradiction between threat and protection. When Ellen and her classmates acknowledge the contradiction, they metaphorically came across an entry point in their development of vocational knowing. That is, reconciling the pressure of being visible to public scrutiny, at the same time being a moral role model. The uniform demands that the wearer upholds a respectable outward projection for the whole security industry. Sara, the instructor, invites 2nd-graders to “put on a costume” to rehearse their make-believe vocation before they commit themselves to it. Vocationalising concepts in classroom settings cannot generally be anything else other than collective testing of meaning-making in light of the students´ limited interaction with working life. For instance, when Sara asks: Has it ever crossed your mind what security officers usually wear?

Pernilla responds: I’ve once seen a girl with a heavy make-up. It looked as if she was just playing, pretending. Totally overdone.

Sara, the instructor replies: It shouldn’t be like that. As a security officer you represent “the company outwards. If I do anything wrong, I smear the whole security industry, we are highly visible in cars painted with logos”. [observation, School A, grade 2, March 2016]

Sara’s feedback is explicit and reproving, “it shouldn’t be like that”. Her response to Pernilla’s comment confirms and reinforces the students’ meaning-making of the uniform as conventional respectability and respectfulness (Valbärj and Nyberg 1997). Such blunt feedback signals to them how well aligned their self-perceived and “real” dispositions need to be with the requirements of the community of practice (Colley et al. 2003; Vincent and Braun 2011). The instructor’s feedback directs the already ongoing (note Pernilla’s remark) process of students´ identification with the security industry as a mark of social respectability denoted by the uniform. Other than this, the industry holds a security officer accountable for his/her conduct.

-

iii)

Accountability to the security industry: Zero Limit

A security officer is accountable to the security industry and its employers. This accountability is articulated by zero limit, communicated as occupational ethics in the training package. Adherence to the zero limit is presented by the instructor as a primary feature of a security officer’s vocational knowing. During a class the students played an ethics dilemma board game. One activity they completed was about a security officer being offered a small birthday gift by a customer. Since they were not able to reach a consensus on the dilemma, they asked Fadi, the instructor, for help. Fadi explained that the zero limit restricted vocational freedom of action: The first rule is “do not take anything”, the other is “do not use the customer’s benefits, resources, equipment and time” and then there is “do not accept gifts” [observation, School A, grade 2, May 2016]. The 2nd-graders struggled to grasp the concept, relying on the instructor’s feedback to “get it right” inferentially, engaging in a space of reasons. Prompted by Fadi’s question about the zero limit, in the first place they tried various arguments, for instance: Things will be different at different workplaces, then you will make mistakes, so how do we not get into trouble?

Pernilla and Anders: The customer

Fadi: Exactly, the customer, good because the customer is in focus. If the customers get angry we lose our jobs so this is the main reason why we have the zero limit, in order not to make our customers angry. [observation, School A, grade 2, May 2016]

Fadi’s feedback swiftly resolved the matter by correcting any misconceptions in a space of reasons they collectively and momentarily inhabited. His feedback moves from the board game situation, i.e., the task at hand, to extend students´ principled understanding of occupational practice. The concept of zero limit reflected the industry’s effort to manage its trust capital, a foundation of the industry’s prosperity (Valbärj and Nyberg 1997). Accountability towards several actors demands a security officer’s canonical occupational knowing which can be enacted in different ways, depending on the varying social structures of security companies (Brockmann 2010; Bijlsma et al. 2016). The students may not fully comprehend nor appreciate its details, even though their grasp of this concept is indicative of emerging specialized vocational knowing. They may not even be ready to step over the threshold of accountability, given their limited experience. It was not surprising that they asked for reasons to align themselves with occupational ethics. Importantly, one facet of specialized knowing is accountability through accomplishment of the uniform.

-

iv)

Modernising the security occupation

During in-school training, students put their previous ideas about the role of a security officer to a reality check. Marcus gives evidence of this: I remember how my view on a security officer as an occupation has changed a lot (…) it is more civil service, you are not there to brawl, you are there to watch [focus group, School A, grade 3, April 2016]. Their conversations proceeded from that of an action film character to that of a contemporary security officer - that is, a scout, janitor, negotiator and technician.

The training package introduces students to a figure of thought, the modern security officer which stands for a security oriented janitor, good at fixture repair. A modern security officer is, according to Robert and Marcus, “cowardly” as far as abstaining from taking any unnecessary risks, and “chooses” his or her fights with the utmost care for self-protection. Caution and concern for one’s security become features ingrained in the vocational identity of security personnel. The instructors’ feedback helps students appreciate how “being cowardly” relates to the specialized vocational knowing of a modern security officer.

Marcus: They (instructors) said that a modern security officer is a coward (…) you never (with emphasis) put yourself at risk because later on you sit there, thinking back “oh, I knocked down that person, saving 17 lives but now I suffer from hepatitis C”, congratulations (with irony).

Robert: Exactly, it is like that, you are supposed to be very cowardly, you should think of your own safety first. [focus group, School A, grade 3, April 2016]

Through peer feedback in the space of reasons, Robert and Marcus reconcile contradictions, that is, the need to protect others and the freedom to choose an action for self-protection. In sum, a constant need for self-protection becomes a driving force shaping specialized vocational knowing. Peer feedback in a focus group collectively changed understanding of reasons underpinning vocational actions.

One facet of a modern security officer that the students were introduced to was the fictitious character of the ninja. The ninja enters the training as part of what Fredrik the instructor calls “ancient knowledge”, giving students an opportunity to earn a distinction, “a black belt in surveillance” [observation, School A, grade 3, March 2016]. The ninja silently moves in the darkness, undetected and always ready for action. The creature is agile, intuitive, watchful and always on guard. The ninja also uses its sharpened senses to position itself spatially. The ninja as a metaphor for specialized vocational knowing of a security officer connects the ancient past with the future. So the ninja refers both to certain ways of meaning-making as well as techniques (e.g., the pie method; the quick peek method). Thus, the instructor’s feedback on the process of integrating many facets of the security officer’s different roles further enhances students´ emerging understandings about a more modern notion of the security occupation.

-

v)

Social, study and professional conduct

Feedback in the Diploma project explicitly focused on social processes of group work, and on students as classmates. Throughout the project, the students were addressed by the teachers as work team mates expected to take responsibility for their own learning and that of their peers, in line with the goals of the Diploma project. So pedagogy as a social and supportive function affects both the content and the kind of vocational knowing that is on offer within a Diploma project. This is perhaps not surprising, given the embeddedness of educational subject matter in pedagogy for human-centred vocational education (Virtanen et al. 2008).

Vocational knowing of a security officer in upper secondary school relies heavily on retaining and honing all the attributes and abilities of a “responsible” student and classmate. When Britt (the teacher) approached a group chaired by Izabel with the help of Tobias, who was the group’s secretary for the day, she encouraged the students to review the official regulation, Fappen,Footnote 4 and divide the work among themselves. In response to a student who asked What legal support do I have to Google? Britt and other students began to make suggestions about what legal support applied in the case of people starting a tussle. Both peer and teacher feedback directed attention to the collective task at hand of drawing up a plan.

Izabel suggests: If we catch someone in the act then we can stop it, if someone says “he took it” then we should call the police.

Britt: What does the document say?

Discussions among second and third grade students concentrated mainly on everyday and commonsense action orientated matters such as what to do when a situation arises, without paying particular attention to regulations. Teachers had to refocus them to think about the application of specific vocational concepts (e.g., relating the situation to legislation) and implications for the occupation. In another instance, the concept of “catching in the act” was met with silence, leading the conversation to take another turn. Ideally, it is more appropriate to particularize it by elaborating on what legal support applies if people start a tussle? And, notably, what are we allowed to do? Thus, the group cannot proceed vocationalising concepts in this instance, since the classmates are by themselves unable to momentarily share a communal space of reasons. The lack of feedback (that is, muted feedback) highlights the difficulty for students in creating entry points (Chan 2016) into vocational knowing without much assistance from the teachers.

The Diploma project for the students in 3rd gradeFootnote 5 concluded with an oral group presentation which finally confirmed for the students the “real” purpose of the group work, namely social skills for team work:

Britt (teacher): So now you have experienced what it is like, suddenly you face a situation where you work with other people than you were supposed to. How do you handle this? Monica’s and my plan was like this, it is not the final product that counts most in the Diploma project but rather it is about team work. Can you handle unexpected events? Are you prepared to work with new group members? [observation, School B, grade 3, May 2016]

When Britt asked her colleague Monica to evaluate, it was general feedback that was called for (Total impression? You struggled keeping up good faith and in good spirits, [observation, School B, grade 3, May 2016]). Monica then went on to emphasize the importance of working independently for those who are about to graduate: We let go a bit on purpose because you are now supposed to be employable … we decided not to carry you through this till the end, but rather to let you take the opportunity to show that you can make it work and take responsibility for it. Thus, the teachers´ feedback was directed at the intangible social dynamics that group work activates (flexibility, making effort, perseverance). This intangibility is mirrored in the teachers´ feedback. Both teachers commented on the students´ collective and individual efforts to make the group work succeed.

Taken together, feedback in the Diploma project mainly reinforces students as classmates, whereas feedback in the training package creates entry points (Chan 2016) by letting students try out an imaginary security officer uniform with the responsibilities entailed in this socio-cultural act. The discourse in the training package moves quickly back and forth between particular, often personal, and more general meanings. Feedback in the training package is meant to shape a modern security officer (ninja, janitor, negotiator, technician and whistleblower). Feedback in the Diploma project, however, is meant to form responsible and independent students and classmates. It can be argued that the space of reasons that the teachers and students inhabited opened up certain inferences about what knowledge counted as valid and legitimate in this group work, as well as what dispositions were desirable for the profession. It is the combination of conceptual, social and dispositional skills of being a student that underpins vocational knowing for group work in the Diploma project.

Summary and Discussion

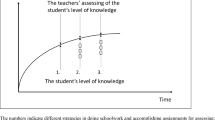

The study examined how young people vocationalised concepts that contributed to vocational becoming as security officers. The role feedback played in the process was also analysed. Concepts that students vocationalised included conceptualisation of anomaly as a vocational tool. Students also accomplish the uniform, displaying their accountability in its several facets, and reconciling its built-in contradictions. By revisiting prior understandings, students align themselves with the ideal of a modern security officer that includes roles as janitor, ‘ninja’ and negotiator. They transform vocational concepts into general tools for practicing social, study and professional conduct. Drawing on the analyses, we extricate some general conclusions to explain the process of vocationalising concepts in readiness for vocational becoming. The two classroom strategies (through the training package and the Diploma project) invite students to inhabit different spaces of reasons, enabling vocational becoming on different terms. Teacher-led instruction and feedback provides more opportunities for vocationalising concepts, thus strengthening security officer vocational becoming, whereas student-led instruction strengthens the students for studentship, offering considerably fewer opportunities for vocationalising concepts. Vocationalising concepts in a school setting is a socio-cultural, constructivist act, embedded in pseudo contexts for particular vocations. Meaning is co-constructed, socially appropriated and augmented by feedback on the process of understanding in a space of reasons. Feedback for vocationalising concepts in classroom situations is contingent on whether feedback is part of teacher intervention that focuses the process rather than a particular task. Feedback offers situated opportunities for the creation of entry points for becoming a security officer.

The research sheds light on vocational discourses and pedagogies (e.g. through feedback) within upper secondary vocational school, which shape vocationalising of concepts and vocational becoming. Pedagogical considerations, for example, the choice of teacher directed or student-led feedback to a heterogeneous group of students, can limit the scope of vocational becoming that is available to students due to time constraints and nature of the space of reasons. The training package offers teacher directed instruction (Vestergaard Louw 2013) whereas the Diploma project is loosely organized as student-led, mixed-grade group work. Teacher interventions for heterogeneous group projects in the Diploma project make it challenging for teachers as well as students to occupy the same space of reasons for meaning-making through inferences (Brandom 2000; Derry 2008; Guile 2006). In the Diploma project the students have the freedom to create a space of reasons for themselves, guided only by their current level of competence, with limited peer feedback to expand understanding. Student-led instruction limits their efforts in advancing above the concrete - fracturing and fragmenting the process of restructuring generalizations (Vygotskij 1934).

This study sheds light on how students in USVET become initially conversant with concepts from an occupational body of knowledge that is entirely novel to them. However, incorporating an industry training package into USVET is not a customary feature of USVET. Some young prospective security officers may feel positively singled out and enjoy more attention than their peers. In comparison with other service occupations that the Child and Recreation Program trains for, the students in this study may count on relatively stable employment in a fast growing sector, providing they comply with the requirements and scrutiny from the security industry. Hence, students´ motivation to effortfully engage in educational activities may be greater.

The research opens a promising line of inquiry into how teachers in vocational schools can enhance feedback strategies and processes by considering a group’s make-up, students’ current knowledge and understanding and its alignment to vocational practice. The act of vocationalising concepts relies heavily on students´ ability to share a communal space of reasons. However, not much is known about students’ understanding and engagement in communal space of reasons. We advocate more research into how pedagogical considerations and teacher-led interventions hamper or enhance students’ approaches to vocationalising concepts; and how the process can be further augmented through feedback. As it stands, school-based USVET offers distinct (and not sufficiently researched) opportunities for teachers to create a space of reasons conducive to feedback that enables students to vocationalise concepts. Despite the small scope of this study, it shows how feedback that enhances vocational becoming is most useful in a shared space of reasons, albeit through a collective (student-peer-teacher) process of justifying reasons. Feedback through student-led constellations (and not just due to classroom setting) primarily enhances their identity as students and presents fewer opportunities for vocationalising concepts aligned with occupational performance. However, this may not pose a problem for young prospective security officers in the Diploma project whose broad social skills can be easily morphed with occupation specific knowing because they are more exposed to practical opportunities when completing their projects. Conversely, those relying mostly on classroom settings (e.g. USVET students) may experience limitations in socializing vocational concepts.

Conclusion

The findings of the case study suggests that vocational becoming is contingent upon students developing conceptualized vocational knowing in a field where formalized training is relatively recent and still quite rudimentary. Vocationally relevant concepts are developed inferentially and feedback augments the process by bringing together and bridging understandings in a collectively created space of reasons. Feedback at the process level is contingent on contributions from more knowledgeable others to collectively construct inferences within space of reasons. For young security officers-to-be, engagement in the space of reasons is conducive to interrogation, condensation of meaning, selecting appropriate actions based on the need for self-protection, and connecting the particular with the general. The findings support that conceptualized vocational knowing is necessary for vocational becoming, that is, as a socio-constructivist process of meaning-making facilitated through feedback in general, and feedback at the process level, in particular.

Teacher-directed instruction and feedback has its value not only as a means of enculturating students into a practice community of security officers, but also empowering students to deduct, justify, give and ask for meanings and their appropriation. The findings highlight the role of vocational teachers in creating a space of reasons for vocationalising concepts, and subsequently for vocational becoming. Vocationalising concepts cannot therefore be reduced to abstractions or “theory” that students can access either directly (e.g. from the teacher) or by themselves (e.g. from learning materials). It advances through teachers’ efforts in situating concepts in a space of reasons that they collectively and temporarily inhabit. For instance, in the Diploma project the mix of students in grades 2 and 3 contributed to collaboration for vocationalising concepts across the grades, with more experienced students in Grade 3 sharing richer understandings. Grade 2 students demonstrated similar levels of understanding only after they had attended the first part of the training package. Only then did they grasp vocational concepts which became meaningful to them in a novel space of reasons. They then showed more appreciation of feedback from older peers and teachers. Given the significance of feedback, more research is needed to expand the scope of vocationalising concepts in school-based classroom settings. Specifically, research on how collaborations with various contributors (i.e. in schools and in work settings) can improve vocationalising concepts, thus advance current practices and processes. More research into feedback to build social skills and capacities through interactions in people-centred vocational programs is also necessary. This will also inform training on feedback as a multi-purpose didactic tool for vocational teachers.

Overall, the findings show that collective meaning-making, supported by feedback, contributes to vocationalising concepts to construct specialized knowledge that forms the foundations for entry points (Chan 2016). Students are required to construct appropriate meanings of vocational concepts in ways that are aligned with what is expected of them in terms of becoming a competent worker in their chosen vocation (Billett 2011). Hence vocationalising concepts is central to their learning and preparation for work. Respectively, feedback from peers, teachers and other experienced persons also has significance for enhancing the process of vocationalising concepts. Hence, all agents involved need to develop skills in giving constructive feedback, thereby enhance practices and processes for vocationalising concepts.

Notes

BYA stands for Bevakningsbranschens yrkes- och arbetsmiljönämnd. It is an umbrella association representing the interests of both employers and employees through collaboration with trade unions.

Intermittently and according to the timetable, that is, a whole school day for the training package in School A and one lesson for the Diploma project in School B.

SKÖLL is an acronym for a method to detect anomalies. It stands for “stop-feel-overview-listen-smell”.

Fappen is an abbreviation and it refers to Rikspolisstyrelsens föreskrifter och allmänna råd till lagen (1974:191) och förordningen (1989:149) om bevakningsföretag. (RPSFS 2012:18) FAP 579–2 [the National Policy official regulation and recommendations to the Act (1974:191) and the ordinance of the security industry (1974:191)], https://polisen.se/Global/www%20och%20Intrapolis/FAP/FAP579_2_RPSFS2012_18.pdf, accessed 2016–04-25.

The students in grade 2 continued their Diploma project.

References

Bevakningsbranschens yrkes- och arbetsmiljönämnd Väktarskolan (2015). Grundförfarande för bevakningspersonal: BYA handbok. [Basic methods for security industry personnel: BYA handbook] (2nd ed). Kista: BYA Väktarskolan.

Bijlsma, N., Schaap, H., & de Bruijn, E. (2016). Students’ meaning-making and sense-making of vocational knowledge in Dutch senior secondary vocational education. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 68(3), 378–394.

Billett, S. (2011). Vocational education: Purposes, traditions and prospects. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Billett, S. (2014). Integrating learning experiences across tertiary education and practice settings: a socio-personal account. Educational Research Review, 12, 1–13.

Brandom, R. (2000). Articulating reasons: An introduction to inferentialism. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Brockmann, M. (2010). Identity and apprenticeship: The case of English motor vehicle maintenance apprentices. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 62(1), 63–73.

Chan, S. (2013). Learning through apprenticeship: Belonging to a workplace, becoming and being. Vocations and Learning, 6, 367–383.

Chan, S. (2016). Assisting with qualification completion by applying the concept of occupational identity as conferred before self-inference: A longitudinal case study of bakery apprentices. Vocations and Learning, 9, 1–20.

Colley, H., James, D., Diment, K., & Tedder, M. (2003). Learning as becoming in vocational education and training: Class, gender and the role of vocational habitus. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 55, 471–498.

Cornell, K. K. (2017). Feedback. In J. L. Hodgson & J. M. Pelzer (Eds), Veterinary medical education: A practical guide, (pp. 273–285). John Wiley & Sons.

Delamont, S. (2008). For lust of knowing - observation in educational ethnography. In G. Walford (Ed.), How to do educational ethnography (pp. 39–56). London: Tufnell Press.

Derry, J. (2008). Abstract rationality in education: From Vygotsky to Brandom. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 27, 49–62.

Diphoorn, T. (2016). “Surveillance of the surveillers”: Regulation of the private security industry in South Africa and Kenya. African Studies Review, 59(2), 161–182.

Gibbs, A. (2012). Focus groups and group interviews. In J. Arthur (Ed.), Research methods and methodologies in education (pp. 186–192). London: Sage.

Guile, D. (2006). Learning across contexts. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 38(3), 251–268.

Heusdens, W. T., Bakker, A., Baartman, L. K. J., & de Bruijn, E. D. (2016). Contextualising vocational knowledge: a theoretical framework and illustrations from culinary education. Vocations and Learning, 9, 151–165.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Manzo, J. (2012). On the practices of private security officers: Canadian security officers' reflections on training and legitimacy. Social Justice, 38(1/2), 107–127.

Merry, S., Price, M., Carless, D., & Taras, M. (2013). Conclusion and reflections. In S. Merry, M. Price, D. Carless, & M. Taras (Eds.), Reconceptualising feedback in higher education: Developing dialogue with students (pp. 204–209). Abingdon Oxon: Routledge.

National Police Authority. (RPSFS 2012:18). Retrieved from https://polisen.se/Global/www%20och%20Intrapolis/FAP/FAP579_2_RPSFS2012_18.pdf

Sandal, A. K., Smith, K., & Wangensteen, R. (2014). Vocational students experiences with assessment in workplace learning. Vocations and Learning, 7, 241–261.

SNAE. (2011). Upper secondary school 2011 [Gymnasieskola 2011]. Swedish National Agency for education [Skolverket]. Stockholm: Fritzes.

Tanggaard, L. (2007). Learning at trade vocational school and learning at work: Boundary crossing in apprentices’ everyday life. Journal of Education and Work, 20(5), 453–466.

Thomsson, H. (2010). Reflexiva intervjuer [reflexive interviews] (2nd ed.). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Valbärj, K., & Nyberg, D. (1997). Väktarbranschen - en bransch med anor [security industry-an industry with traditions]. In Alla dagar alla nätter-fyra transporthistoriska essäer (pp. 191–219). Stockholm: Svenska transportarbetarförbundet.

Vestergaard Louw, A. (2013). Indgang og adgang på erhvervsuddannelserne: analyse af tømrerelevernes muligheder og udfordringer i mødet med faget, lærerne og de pædagogiske praksisser på grundforløbet [entrance and access to vocational training: An analysis of carpentry students´ opportunities and challenges in the encounter with the subject, the teachers and the pedagogical practices in the basic course]. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://viden.sl.dk/media/5249/indgang-og-adgang-paa-erhvervsuddannelser.pdf

Vetenskapsrådet [Research Council]. (2017). God forskningssed [good practice research]. Retrieved from https://publikationer.vr.se/produkt/god-forskningssed/.

Vincent, C., & Braun, A. (2011). ‘And hairdressers are quite seedy...’: The moral worth of childcare training. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 11(2), 203–214.

Virtanen, A., Tynjälä, P., & Stenström, M.-L. (2008). Field-specific educational practices as a source for students' vocational identity formation. In S. Billett, C. Harteis, & A. Eteläpelto (Eds.), Emerging perspectives of workplace learning (pp. 19–34). Rotterdam: Sense.

Vygotskij, L. S. (1934), Myshlenie i rech. Retrieved from https://vk.com/doc27441302_400797894?hash=7f71a268e35ce85ae5&dl=ddaecf3dcba0167848

Acknowledgements

This article is part of a doctoral dissertation at the Department of Education and Special Education, the University of Gothenburg. The outline of this article and some data were presented at the annual European Conference on Educational Research-ECER, Dublin, Ireland, 23-26 August, 2016. This paper was developed during the first author’s short professional attachment with Griffith Institute for Educational Research, Griffith University. The hosting and support provided by the institute are duly acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Johansson, M.W., Wärvik, GB. & Choy, S. Vocationalising Specialized Concepts: Appropriating Meanings Through Feedback. Vocations and Learning 12, 197–215 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-018-9204-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-018-9204-4