Abstract

The general rise in contractors, particularly among knowledge workers negotiating ‘boundaryless’ employment conditions, has generated interest in the nature and forms of contract work. This article explores the learning of contract workers as they negotiate these conditions, with a focus on women. Drawing from a qualitative study of women practicing nursing and education in Canada as self-employed contractors, the discussion focuses on the practices that they learn in order to manage their work activities and identities. In these practices, tensions abound – particularly around the recognition of knowledge in ways that establish the contractor’s identity, position within the organisation, and market value. For women, it is argued from the study findings, boundaryless contract work incurs particular gendered demands that embed contradictions that the contractor must learn to negotiate. This article describes five practices that women contractors learn within these contradictions: (1) being noticed while avoiding notice, (2) nailing down contracts without nailing the contractor, (3) performing a woman in control while hiding the chaos, (4) shape-shifting while ‘branding’ one shape, and (5) proving knowledge in a market of impressions. The article concludes with implications for education that might assist women contract workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The increasing flexibilisation of work in OECD countries is particularly visible in the case of contract workers, whose numbers appear to be rising in North America, Europe, and Australia (Barley and Kunda 2004). This discussion focuses on the learning of self-employed contract workers, who have been described variously in the literature as contractors, freelancers, independent professionals, ‘itinerant experts’ (Barley and Kunda 2004) and ‘boundaryless workers’ (Arthur and Rousseau 2000; Hanson and Hagström 2003). The term ‘boundaryless’ has emerged to acknowledge the unique spaces and the concomitant challenges when individuals must construct the boundaries defining their work knowledge, work activities, environment, identity, and the specific services they are selling to client organisations. These spaces of boundaryless work are fraught with contradictions and difficulty (Brocklehurst 2003), which shall be described further on. For women in boundaryless contract work, the conditions can be especially difficult: this space is genderedFootnote 1 and almost completely unprotected by any equity regulation.

Learning often becomes left aside in the discussions of working conditions and regulatory protections for contract ‘boundaryless’ workers. What practices do contract workers learn in order to manage the ‘boundaryless’ conditions and spaces of their work, particularly women contractors? This discussion explores this question using findings of a qualitative study that examined narratives of Canadian women contractors in knowledge work moving across multiple organisational boundaries – hence, ‘boundaryless’ – in the general fields of nursing and education. These individuals were not necessarily entrepreneurial in the traditional sense of being drawn to the supposed freedom and growth potential of owning their own business. Instead, they usually were inducted at the beginning of their working lives into particular professional identities embedded in institutional communities such as schools and hospitals. However, through various changes in Canada’s economy (i.e. 1990s recession followed by a jobless recovery of organisational cost-cutting, downsizing and restructuring) combined with an ascendancy of entrepreneurial discourses, these professionals found their way to self-employed contract work. Their narratives reveal what happens when people are thrown into boundaryless work conditions. Frequently surprised by the actual demands of such work, these women learned particular practices to negotiate its contradictions. Their efforts draw attention to under-recognised dynamics in contract work and problems in its conditions. The focus here on gender echoes issues that have been well-reported on women employees in organisations (e.g. Probert 1999; Simpson 1998), but that deserve to be recalled in discussions of contract work conditions.

This article begins with an overview of boundaryless contract work and its gendered elements reported in existing literature, and then discusses practice-based learning theory. The next section proceeds to describe the study methods, and the third section outlines particular conditions of boundaryless work reported by women in contract work. The fourth section describes certain contradictory demands of contract work perceived by these women and the practices they learned to work within these contradictions: (1) being noticed while avoiding notice, (2) nailing down contracts without nailing the contractor, (3) performing a woman in control while hiding the chaos, (4) shape-shifting while branding one shape, and (5) proving knowledge in a market of impressions. As the discussion will indicate, these practices combine strategy of managing employment conditions and relations with practices of identity, all of which are closely linked to contractors’ sense of the ‘knowledge’ they are contracting to clients.

Boundaryless Contract Work

Boundaryless contract work is a form of ‘own account’ self-employment (i.e. no employees besides the owner-operator) in which individuals contract their knowledge to different employers in a variety of contexts. Terminology denoting self-employed types of boundaryless work becomes blurry: ‘freelance’, ‘contract’, ‘non-traditional work’ and ‘self-employment’ appear in career literature addressing this phenomenon. Self-employment is a broad category, including business owners/employers as well as independent entrepreneurs producing and selling goods. Contractors such as those discussed in this article may be self-employed, but their work is often entirely knowledge-based and linked to others’ organisations and enterprises rather than being stand-alone enterprises. For this reason, the term ‘boundaryless contract work’ is used here rather than ‘self-employment’. Three common elements that distinguish boundaryless contract work are: (1) a commitment to long-term, rather than temporary freelance employment – as a way of life rather than a ‘stop-gap’ measure; (2) a sense of specialised expertise being developed and offered; and most important, and (3) job mobility across Boundaryless careers have been studied most often in terms of the personal transitions involved, and the construction of a career identity outside of organisational definitions (Cohen and Mallon 1999; Gold and Fraser 2002; Sullivan 1999). Contract workers may struggle with anxiety, lack of income security and non-income benefits, and continuous competition (Gold and Fraser 2002). Contract workers are often marginalised within organisations. Recently, for example, Hoque and Kirkpatrick (2003) found, using data from the UK Workplace Employee Relations Survey, that even managers and professionals on non-standard contracts become marginalised in terms of training opportunities and consultation at work. Further, individuals regulate themselves to accept full responsibility to market their own knowledge and labour, and to mold themselves to be whatever their client organisations may demand (Hanson and Hagström 2003).

What constitutes their ‘knowledge’ is particularly complex. As Alvesson (2001) points out, knowledge workers such as consultants tend to use uncertain, shifting knowledge that is essentially ambiguous in its content, significance, and results. In fact, Alvesson (2001) shows that the contracted knowledge (i.e. through consultants) that is most valued by organisational employers tends to rely most upon image impression, rhetorical intensity, and social connections. This ambiguity leads to a shakiness and vulnerability that makes it difficult for contract workers to establish their credibility and to secure their identity. In studies of freelance media workers, Storey et al. (2005) found much of their knowledge tied up with both disciplining and judging their identities while protecting these identities in experiences of rejection, loss of income and loss of mastery. Clearly, the ‘knowledge’ of contracted workers such as the women featured in this article is definitionally heterogeneous and difficult to categorise. Overall, outcomes of income and identity insecurity, knowledge ambiguity, and general marginalisation appear to be inherently related to the in-between space of boundaryless work. Hoque and Kirkpatrick (2003) are among those who have found that these outcomes are especially strong in the case of women. Thus, the effects of gender in these dynamics raise additional questions that deserve attention.

Women in Contract Work

The majority of temporary contract workers in Canada are women (Statistics Canada 2000). Self-employment, such as contract work, has been particularly promoted for women in Canada as a site for full gender equality, economic opportunity, flexibility, freedom, and self-determination (Industry Canada 1999). However on average, self-employed Canadian women, including temporary contract workers, take home one-third less income than self-employed men (Industry Canada 1999). Self-employed women continue to experience difficulty accessing financing, powerful networks, and resources of support and information (Hughes 1999; Mukhtar 1998).

Studies show that self-employed women contractors based at home, which is their typical employment base, struggle with blurred lines and conflicts between home, family and work (Mirchandani 2000; Tietze and Musson 2005). Particularly for contract workers who say they often are expected to provide almost ‘100% beck-and-call’ response to client demands and unexpected crises (Hanson and Hagström 2003), women with care-giving responsibilities can often be caught in double-binds. Brewer (2000) reports that this lack of recognition for work tasks conducted outside the purview of managers and ‘normal’ office hours disadvantages contract workers, particularly women.

In terms of knowledge, which often forms the core of a contractor’s service, gendered hierarchies continue to undervalue women’s knowledge (Probert 1999). Women contractors must deal with institutions and corporations configured by the larger gendered structures of organisation, finance and knowledge made familiar by many commentators (Acker 1990; Probert 1999). Contract workers who must continually re-negotiate their own terms of employment begin at a disadvantage if their knowledge or approach to service is considered less powerful or reliable than that offered by their male competitors. Further, there is evidence that some women do not negotiate contracts aggressively, as the autonomous, competitive lone ‘agent’ self-interestedly seeking the best conditions and job (Mukhtar 1998). Consequently, such individuals can be disadvantaged in open contract competitions. Altogether, women contractors are confronted by the necessity of learning practices to negotiate the gendered conditions influencing their value, relationships, income and workload.

Learning Practices in Boundaryless Work

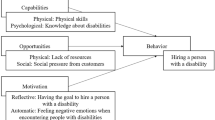

This discussion adopts a socio-material activity conception of learning in work, where learning is understood to be practice-based: embedded in everyday action and arrangements of work (Beckett 2001; Bratton et al. 2003). Learning can be understood as change in consciousness or behavior that expands human possibilities for flexible and creative action. This orientation echoes Engeström’s (1999, 2001) conception of ‘expansive learning’: learning what is not there, creating new knowledge and transforming objects, people and activity. However cultural–historical activity theory as popularised by Engeström, while useful, is only one approach to understanding learning and the emergence of practices. Other useful perspectives include Wenger’s (1998) constructs of engagement, belonging and identity in communities of practice, Latour’s (2005) emphasis on ‘translation’ and mobilisations of both human and non-human actors in networks of action, and Davis and Sumara’s (2006) application of emergence, complicity and simultaneities from complexity science. Each has its limitations, but all share a focus on material practice as embedding symbolic and discursive practice, an analysis of power dynamics constituting forms and recognition of knowledge and practice, a systemic view of learning collectives, and insistence upon tracing inter-objectivity in practice formation rather than stopping at the social constructivist level of inter-subjectivity (Fenwick 2003, 2007a).

While individual change can be observed and explored, practice-based conceptions understand such change to be continuously interactive and ultimately inseparable from the social, cultural, political, spatial and material dynamics enacted in everyday practices of the collective. Thus practice-based learning is partly a cultural phenomenon: the cultural norms, accepted practices, relationships and of course the history(ies) of a particular work community constantly realises what is considered useful knowledge and practice, and what and how new practices emerge (Wenger 1998). Contradictions, inherent within all systems, trigger learning when they are questioned and resolved (Engeström 2001). At the level of individual actors, practice-based learning is also understood to be closely tied to people’s identities generated in their work, which change over the career course (Chappell et al. 2003). Overall, the embedding of learning in these multiple layers of practice makes it difficult for individuals to be aware of, let alone to articulate and interrogate the process and outcome of learning.

In terms of self-employed workers such as the contractors featured in this article, studies have found that their practices are constituted in multiple fluid networks (virtual, social and material) rather than boundaried organisational hierarchies, and that they learn largely through practice-based experimentation in these networks (Cope and Watts 2000; Gold and Fraser 2002). The knowledge and identities yielded are flexible, provisional and reflexive. My own studies have shown that they learn practices of managing fluid boundaries (Fenwick 2003), negotiating identity and desire across different work spaces (Fenwick 2007b), and bridging and translating knowledge (Fenwick 2006). Overall, from this practice-based perspective of learning, the questions are not about what meanings people construct and how these change, but: How do particular practices emerge in particular contexts of work? What identities and knowledge are generated by these practices? And more to the point for educators, how can practices be reconfigured to enable more expansive environments and identities?

Study Methods and Participants

What practices do women contractors learn in order to manage these boundaryless work conditions? This question launched the study, which used an in-depth interpretive approach following Lincoln and Guba (2000) and Ely et al. (1991) to explore the unique demands and learning in their work narrated by ‘boundaryless contract workers’. For purposes of this study, this group is defined as women who contract their services to various organisations and clients in a variety of employment relationships. This article focuses on 31 in-depth interviews conducted with women based in three Canadian cities (in British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario) who described their work in these terms. Participants were all professionally trained, and recruited from two general areas for purposes of comparing major differences in work conditions: nurses (N = 13), and educators (N = 18). Nurses provided clinical services (i.e. foot care, palliative care), consulting services (i.e. sexual health consulting, holistic health care, sports health), as well as research and program design in areas such as public health education and addictions. Educators taught courses for colleges and universities, led training, leadership and program development, conducted program evaluation and other research, and provided organisational consulting and development services. About half of all participants contracted mostly with organisations, and half mostly with individuals (e.g., providing personal services like foot care).

Participants were solicited through invitations published on professional listserves and in newsletters. All were ‘mid-life’ ranging in age from mid-30s to mid-50s. Most are well-educated. Among educators, all had graduate degrees. Among nurses, eight had a Bachelor of Science, two had graduate degrees, and three had a nursing diploma. Participants were somewhat homogeneous in race–ethnicity: all but one nurse and all but three educators are white. Overall, a degree of mobility and social and cultural capital was enjoyed by many participants in these two groups, though gender issues such as difficult work–family balances were evident.

Interviews explored participants’ experiences and strategies in two general areas: (1) the conditions of boundaryless work and (2) their learning and knowledge developed in boundaryless work. In-depth interpretive analytic procedures (Ely et al. 1991) were used to create a narrative representing each participant’s experiences as a trajectory within a particular professional and socio-cultural context of work. Broad common categories were identified across these narratives related to boundaryless contract work conditions and learning (i.e. types, content, process) experienced by participants related specifically to managing contract work. Then, working from these categories, transcripts were coded and categorised at increasing levels of abstraction to discern common themes and differences, as well as tensions evident within these themes.

A major limitation is the study’s focus on professional workers, and mostly white urban women. Visible minority women and women whose primary cultural affinity is not Canadian, such as one Chinese Canadian and one Indo-Canadian interviewed, report additional difficulties in contract work that are not captured in the general findings here. It can be anticipated, too, that non-professional contract workers such as tradeswomen, or contract workers in clerical, custodial or hospitality sectors, would report struggles with sexism, precarious conditions and low income requiring particular strategies that are not reported here. Further, the helping professions chosen for reasons of finding large numbers of women – nursing and education – might be characterised as rather conservative in forms of practice and stable in contexts of practice, compared with contract knowledge workers in, say, hi-tech industries. Whatever the characteristics of these professions, it is reasonable to assume that the disciplinary forms of knowledge would have some effect on the approaches to learning adopted by their practitioners. Finally, the study methodology relied on narratives which are limited to individuals’ recall and representation of their practices. These narratives are, of course, partial and provisional, as are the interpretive representations wrought in the writing and reading of this text.

General Conditions of Boundaryless Contract Work

To better understand the findings related to contractors’ learning, some awareness of context is important. Therefore, this section presents a brief glimpse of participants’ views of their working conditions. All participants had moved into boundaryless work from employment in a small or large organisation. All claimed that they had freely chosen the form of self-employment here called boundaryless work. Their reasons are consistent with those described in self-employment literature including ‘push’ motives (i.e. frustration with repressive organisational structures or difficulty finding full-time employment in their preferred practice), ‘pull’ motives (i.e. desires for flexible work schedules, freedom from supervision, or urge to create a personal practice), or a push–pull combination (Cohen and Mallon 1999). However, it is by now well-recognised that the notion of ‘choice’ is problematic, and may more accurately represent received cultural discourses emphasising individuals’ responsibility for their own conditions than an individual’s exercise of agency. Even though some of the interviewees here may have believed they freely chose to leave employment, they may in fact have had little choice in cases where work conditions were intolerable, no full-time work was available, or future staff cuts were inevitable.

Nurse and educator contractors both must deal often with conservative institutions (e.g. schools, colleges and hospitals) governed by typically rigid occupational classifications, credentialling processes, and operational procedures.

I first started – there was tremendous resistance to it. Like I wasn’t allowed to go into a hospital setting and do healing touch with a patient in the hospital. Now I can go and do that. Provided that the doctor is informed and has no difficulty and the head nurse has no difficulty with it. (Betty, nurse, ll. 863–866).

Additionally, because nursing and education are usually publicly funded and considered helping professions, institutions and the public are unused to paying individuals for contracted services. One explained, ‘My challenge was: how could I get a patient to pay me for my nursing knowledge?… And the hospitals don’t know how to contract with us. They don’t know any other billing practice than pay them a salary’ (Gilda, nurse, ll.220–22, 483–485). All of this means that contract nurses and educators report difficulty not only negotiating the terms of employment, but in being recognised as workers. As one noted rather ruefully, ‘My ten year old said to me the other day, you know mom, yours is an invisible job.’ (Dulce, nurse, ll. 1148–1149).

Juggling contracts is a common difficulty. Offers are unpredictable. To ensure adequate income, contractors often say ‘yes’ to everything except the truly distasteful or overwhelming opportunities. This can mean overload work crunches that can be excruciating, with no one to help ‘backfill’ the load. Meanwhile, each employing client has its own schedule for completion, and its own emergencies and other unexpected project problems that the contractor is expected to absorb. Lauren explains, ‘It’s a constant battle. My tendency is to go–go–go, and then collapse…. You are hired for a deliverable, and it’s up to you how you get there. So that’s the attraction and the curse’ (Lauren, educator, ll.189–190). A key problem for some women contracting in the fields of education and nursing is difficulty commanding incomes commensurate with the salary they might obtain as a full-time employee doing the same work:

I have got more offers to teach or to write or to do contract research than I know what to do with. But I mean, they’re not well paid, and they don’t allow me the time that I need to actually do the research.’ (Peg, educator, ll).

Over half of the participants alluded to feelings of restlessness, seeking new challenges after working a few months or years in one place or type of employment. Yet amidst this apparent need for contingency, they also claimed to need a stable focus. This dynamic has been described elsewhere (Fenwick 2007b). It seems driven partly by business purposes, to clarify a niche and build long-lasting relationships with particular clients and partly by personal need for a sense of place, identity, security and boundaries defining one’s life and work in the fluidity of boundaryless work. These two desires – for resilient, often intentional career contingency and for focus and stability – appeared to exist simultaneously as a central tension in the work and subjectivities of boundaryless workers (Fenwick 2007b). Further, they experienced related internal conflicts within the most positive dimensions of boundaryless work (Fenwick 2006). One was the work design element of boundaryless contract work, involving negotiating boundaries in the structure, process, standards, environment and content of their work activities. Another conflicted area was client relations, requiring boundaries delineating credibility, reciprocity and mutual expectation to sustain relationships with multiple clients. In both of these areas, boundaryless workers talked of experiencing both freedom and repression simultaneously.

These central contradictions, and the transition to contracted work, are not foci in the following discussion of what women learned as they negotiated boundaryless work. However, these conditions inform analysis of the practices these women say they have needed to learn to negotiate boundaryless contract work successfully.

Learning Contract Work: Negotiating Contradictions

Women describe their work activity in terms of highly complex negotiations of these conditions and contradictions. The practices they seem to learn to function within them have been organized into five categories, described in the following sections: (1) being noticed while avoiding notice, (2) nailing down contracts without nailing the contractor, (3) performing a woman in control while hiding the chaos, (4) shape-shifting while ‘branding’ one shape, and (5) proving knowledge in a market of impressions. These areas each embed contradictions that must be worked through by these women contractors, often in isolation.

Being Noticed While Avoiding Notice

To be hired, the contractor must promote herself to catch the eye of potential client. This is why networking is considered so crucial. In some sectors, such as education and its related fields of training and organisational development, contracting is particularly competitive. Self-promotion must begin with figuring out what employers need or think they need, and what sort of solutions they value. Women say the key to being noticed is then to distinguish oneself from the pack as offering unique knowledge or approach that can help that employer. Some took a more conventional approach using assertive marketing:

When you introduce yourself to somebody, what do you say? ‘I’m a nurse.’ And assume they know what that is? What you know is not as important as being able to market yourself and your services. How do you know who’s out there who needs you? Are you going to wait for them to ask? No, no. You have to write your business brochure in a way that says, ‘if you’ve got this question you need me’. (Gilda, nurse, ll. 676–681).

Others, however, avoided self-marketing and relied on creating a reputation of excellence and strong relationships among a selective network to be recognised. A major threat to being noticed is the contractor’s inherent position as an outsider to an organisation: ‘Appearing and doing something and disappearing – who was that masked woman?’ (MM, educator, ll. 363–366). Women talked of strategies to promote their visibility such as producing particularly useful innovations. Or, they tried to ensure that they were able to negotiate their work with sufficiently senior managers that the project would have some ‘legs’ in the organisation rather than disappearing into the flow of everyday work. However, at the same time the contractor needs to blend with other employees, ensuring that she is not perceived to enjoy unfair privilege and visibility. Some employees already resent the contractor whose daily billable rate may exceed staff take-home pay for the same hours.

You’re basically bringing common sense, you don’t know much more than the people that have worked in the organisation for years, but you are treated like the second coming by some managers. You’d better tread softly. (Tarya, adult educator).

Treading this line carefully is an important skill. The contractor’s success in a project and chances of being hired back often depend on being noticed as special by management while managing not to alienate staff, in fact cultivating collaborative and trusting work relationships with staff.

Nailing Down Contracts Without Nailing the Contractor

The strategies of contract negotiation are another skill area that contractors need to learn. Women said that to avoid misunderstanding and unmet expectations, they had to figure out how to anticipate every aspect of an activity, then figure a balance between reasonable compensation and what the client would be willing to pay. These contractors were often surprised that routines for such contracts were not in place in employing organisations. The responsibility then falls to the contractor to plan ahead and ensure that the contract addresses every aspect, including contingencies: precise objectives, access to equipment and space for the work, payment schedules, fair timelines, and what constitutes completed work. Women said that, still, they often found themselves personally absorbing the project overruns and myriad unanticipated details or problem-solving, in an effort to please the client and prove their worth. Unanticipated labour is particularly frequent in knowledge work which often cannot be neatly contained as concrete activity with clear temporal boundaries:

It took a while to really, really define the requirements of the project … as we got into it, it was far more complex then we had anticipated. Took way more time and meant that everything else got, you know, I got pressure in other areas, the other areas in my life, trying to make time for that. (Dulce, nurse)

Projects often require follow-up, or ‘evergreening’ work, that employers may expect but forget to negotiate. Some organisations, women complained, are fuzzy about their objectives and expectations, and need help developing the necessary clarity to create a workable contract. In other cases, the organisation’s needs and expectations far exceed the resources available for the contracted work. Again, it falls to the contractor to educate, to define boundaries, to clarify what is feasible and what is not.

Learning how to price one’s service, for some women, is difficult. Billable rates need to include all the non-billable work (e.g. research and development, administrative hours, insurance and licensing, provision for benefits) required to sustain the contractor’s practice. This requires presenting clients with what can seem high rates that some women said they found hard to justify to themselves, worrying that their service may not be worth the pay rate. Learning how to balance this sustainability with empathy for clients is another skill. Educators providing service to non-profit organisations or unions, for example, typically lowered their rates or even occasionally agreed to volunteer their service. Nurses providing service to individual clients, particularly the elderly, often developed sliding rate scales. Perhaps for most of these women within the first five years of contract work, negotiating money was an activity in which they particularly struggled to become comfortable. Two contractors with more than 5 years’ experience had become involved in mentoring other women contractors, and both indicated their perception that women contractors needed particular support and information to become confident in negotiating fair contract payments.

Performing a Woman in Control While Hiding the Chaos

Emotional labour has by now been long recognised as an invisible but exhausting dynamic of work and skill in many service occupations. Women contractors emphasised the stress of unpredictable contract income, inducing them to accept most offers leading to overwork that compounds the stress.

It’s nerve racking because one of the challenges of being a portfolio worker is never quite knowing if you’re going to keep getting work…. So that can be really tough because I therefore say yes to all work that comes my way and then end up tearing my hair out. (TL, educator/organisational developer, ll. 1152–1162).

But tearing out hair, losing one’s temper, or, god forbid, collapsing into tears is tacitly forbidden. This is particularly the case in knowledge contract work where the contractor’s primary role is to serve the client, and where the entire work relationship is centered on one bounded contract of duty. That is, contractors show up and must perform: there is little allowance for the personal ups and downs that longer term working relationships can often absorb. Women contractors accepted as duty their need to hide all of the stress caused by the chaos of serving multiple masters to appear like a woman in perfect control. One educator explained that she was grateful to be able to work at home as a contractor, because when the stress caused her to collapse in serious illness she was still able to work in bed. Others talked of hiding emotions, and learning to appear calm, enthusiastic, and cheerful for clients. Anything less might suggest weakness, inability to do the job, and possibly ruin future opportunities. Additionally, women worked to create the illusion of 100% devotion to each client’s particular needs.

I always try to make the client think that I’m never doing anything else. So I never tell a client that I have another job or that I’m on a deadline, or that I’m busy that week, or that I can’t get around to them cause I’m working on something else. Like I never ever, ever let somebody think that there might be someone else who’s more important or whose work would take away from their work. I always make them feel like they’re the only job, they’re the most important and they’re the only person I’m working on at the moment. (Elena, educator/graphic designer, ll. 384–391).

This performance of complete devotion seemed to be a natural expectation from organisational as well as individual clients. The main problem was that most women contractors were managing multiple clients, with inevitable doubling and tripling of the requisite devotions. Stress was exacerbated in juggling not only the workload but also the hiding of these simultaneous demands, both external and intra-personal. Women contractors learn how to manufacture an image of control that conceals all of this conflict – and they learn it so effectively that they appear sometimes to conceal these conflicts, with their attendant labour and deleterious personal consequences, from themselves.

Shapeshifting While ‘Branding’ One Shape

A fourth practice that women contractors learn is self-branding. This is an extension of being noticed. The boundaryless contractor needs to conceptualise and ‘brand’ her expertise as a billable service that potential clients need. Making this service recognisable and unique, not just to clients but also to themselves, was an important skill:

I can remember the moment when I was in an elevator being introduced to someone and I actually shook their hand and said, when they said ‘What do you do?’ and I said, ‘I’m an organisational development consultant and I have my own business.’ I can remember thinking, Oh my God, that’s sounded so impressive! And I don’t know what got me there. (Genelle, educator/leadership skills developer, ll. 949–954).

At the same time, the contractor needs to flexibly adapt herself to become whatever is needed by the organisation. This means learning how to ‘shapeshift’ in Gee’s (2000) terms, altering her professional image, the knowledge she offers and the disposition she presents, to fit the organisation’s needs. This shapeshifting should not be overstated. Women also emphasised particular values and principles around which they designed their practice, seeking out clients with whom they felt a genuine values fit and sometimes refusing work that they judged to be of questionable worth. However, the wide range of work activities engaged by a typical nursing or educational contractor – sometimes during the same general time period – necessitated a high degree of adaptation. Similarly, the variety of work organisations into which contractors slipped in and out demanded some shapeshifting to function in different cultures and relational nets.

The inherent contradiction that women contractors seemed to need to learn was how to balance the branded identity with the flexible shapeshifting. This balance required frequent identity work, drawing attention to certain unique aspects of their knowledge and style of practice. At the same time, they had to avoid becoming ‘stuck’ in a particular identity, partly because in knowledge work, the worker herself is learning and shifting to new ways of working. ‘You can get locked in. Who I am and what I do has changed, but people see me as what I used to do’ (Estelle, educator, ll. 37–38). The danger in all this identity work, said this educator, was being seen as ‘jack of all trades, master of none’. The skill was learning to set boundaries defining sufficient identity and expertise for credibility, while flexibly meeting changing client demands.

Proving Knowledge in a Market of Impressions

In proving their credibility on the knowledge market, contractors such as nurses and educators came to learn that the conventional paths to employment and promotion in their profession – namely, academic credentials and long-term experience – counted for little. Performance in contracted work is the currency of credentials: the old saw is ‘you’re only as good as your last contract’. But learning this skill of knowledge performance is laced with contradiction. First, performance depends on the particular view and expectations of clients. Subjugating oneself to this view, in knowledge work, means walking that difficult line of appeasing the client’s view while providing knowledge that sometimes challenges that view – a challenge which is precisely what the client is often paying for, but may not appreciate. Second, performance means continuous scrutiny. One is ‘on’ 100% of the time that one is visible by the client; there is little allowance for an ‘off’ day in the way that a long-term employee known for excellence is given space to be sometimes tired or frustrated. Third, one’s reputation of performance is shared through client networks operating in an informal, tacit realm. In this unregulated discursive space, judgments made about a person’s knowledge and trustworthiness can be based on hunches, rumor, appearance and personal prejudices. One organisational developer who often worked in partnership with a Caribbean-Canadian woman, claimed: ‘It’s very much word of mouth and in that respect it’s very privileged too because it’s mostly white people hiring’ (Beulah, educator, ll. 872–873). In a competitive market of service offerings, without the instant status and credibility afforded by employment with a recognised organisation, contract workers must find ways to prove themselves trustworthy to each new client. As one woman explained,

When you say to someone you’re a freelancer they don’t know what to make of you. And they’re not exactly sure whether you’re serious. And they’re not exactly sure where what they tell you is going to wind up. It would be much easier if I could say I’m working for [a large organisation]. (Isla, educator, ll. 529–532).

Fourth, in performance-driven client-judged credibility, some women worried about sliding professional standards, e.g. knowledge judged according to disciplinary, rather than market, criteria:

It’s very market driven, so there’s all kind of competition and people doing that – so there aren’t any quality standards and that’s an issue for me. And how I’ve chosen to deal with that is to become certified in whatever way I can. (DS, educator, ll. 567–570).

Finally, learning how to prove one’s knowledge is a continuous process. For each new contract, each new client, the contractor must begin all over in reproving and performing her knowledge. In fundamental ways, this is an impossible undertaking given the complexity of knowledge and the impressionistic ways it is judged:

Maybe because I’m a woman, maybe because I’m visible minority woman but sometimes more difficult for people to take me seriously because they don’t know the knowledge that I have. They underestimate the values that I have… I have to work harder convincing people in order to make them realise that I do have a great knowledge in Human Rights which [sic] I’ve worked in this area for seventeen years. (Susha, educator, ll. 282–287).

Furthermore, few organisations understand what they really want in terms of knowledge and don’t take the time to figure it out, claimed one nurse:

‘Well, are you selling something?’ ‘Well yes, my knowledge.’ ‘Well, what is that?’ ‘Well, let me tell you about my thirty years.’ And it’s too long a story. (Gilda, nurse, ll. 474–478, 484–486).

Much of this resonates with others’ findings (e.g. Alvesson 2001; Storey et al. 2005) that proving the ‘knowledge’ of contract knowledge work is mostly about managing identity and impression.

Boundaryless Workers and Implications for Education

In these women’s reported experiences of boundaryless contract work, the practices they learned in order to manage contract work were about managing contradictions, building self-image, and positioning their work in spaces where they had no defined position. The particular practices they developed were crafted through experimentation within layers of networks in the fluid and ill-defined spaces commonly associated with boundaryless conditions. These networks embedded contradictions that enmesh the lone contractor. This individual must learn practices to manage the contradiction by enacting something simultaneously with its opposite, such as being noticed while avoiding notice, or nailing down contracts without nailing the contractor. In the process, the women took onto themselves extensive additional labour: educating employers about contracts, hiding work, and hiding stress or exhaustion. They labored to appear completely fit, to adapt to employers’ every need, and to offer knowledge in contexts where, as Alvesson (2001) showed, what is valued as knowledge often depends upon image impression, rhetorical intensity, and social connections.

These practices and labour are not recognised, valued or rewarded on the market, even by the women contractors themselves. Women had little language for these practices, and no forum for their discussion. Thus, most women appeared to learn in isolation without benefit of support, affirmation, resources, or space to develop critical awareness and even analysis of this contradictory element of contracting. And because there was no forum in which to make this learning explicit and available to critical analysis, they became subjugated by its demands. So, they learned to accept work expansion and systemic contradictions without challenge, and to become complicit in creating the illusion of a perfect flexible worker subject.

But gendered patterns more broadly shared among the study participants are also disturbing. Many women seemed ready to turn themselves inside out to be ‘the good contractor’: available, offering valuable and unique service. All seemed to accept as natural and inevitable the round-the-clock hours, some even celebrating this load as ‘freedom’. They also accepted the lack of income security and personal benefits. Two were single women in their mid-50s with no pension, becoming increasing tired and looking for ways to reduce the workload while maintaining a reasonable standard of living. Overwork, exhaustion and stress-related illness were described as consequences of their own choices, and thus their own responsibility. It is important to note here that some contractors accepted complete personal responsibility for their position (e.g. negotiating comprehensive contract details, arranging their own retirement funds and full insurance, etc). In all of these negotiations, as pointed out earlier, women can be disadvantaged from the outset in open contract bidding based on assumptions of a completely autonomous agent, mobile and free from commitments. Further, the whole process of competing for and negotiating work unfolds through informal networked world where racism and sexism can flourish, and where many hours are required to establish and nurture relationships. Most women contractors emphasised building strong relationships with clients. These relational nets often blended personal connection and friendship with work, involving expectations of reciprocity that incurred special obligations (Fenwick 2006). Thus, some women contractors found themselves pressed to provide (unpaid) extras such as development work for courses, planning and follow up meetings, or proposals that sketch out strategies for next steps.

These issues may suggest a need for more protective regulation for contractors, or more formal organising of contract workers for bargaining purposes. However, the discussion here focuses on aspects of learning and education in the case of women contractors. In these respects, the foregoing discussion suggests that educators have a role to play in helping women contractors to understand and learn vocabulary for the contradictory conditions of ‘boundaryless’ contract work, and the practices that some learn to manage these conditions. Compliant efforts to be noticed, to hide anxiety and stress, to shapeshift while branding oneself, and to prove/reprove one’s credibility can be critically analysed once they are named and discussed. Systemic gendered work conditions and gendered knowledge dynamics, so often invisible to working women, need to be acknowledged, and their effects made visible in everyday transactions of women contractors. All contractors, particularly new ones and not just women, also need education in negotiating comprehensive contracts: in terms of work content, negotiation process, minimal contract provisions, reasonable pay rates that accommodate the entire work effort, contractor’s rights and protections. Educators can also help contractors consider the extra labour embedded in of the practices of negotiating boundaryless conditions of contract work discussed in this article: managing emotions and balancing contradictions. These might have implications for planning one’s work, or even for negotiating the work terms. Finally, educators should consider educating employers about their responsibilities in better provision for women contractors. Employer clients and organisations that hire contractors infrequently may be struggling to understand how to plan for, integrate and support a boundaryless contract worker’s service effectively. They may be unaware of the contingencies that often arise, the gender dynamics at play, and the ‘backstage’ issues that contractors are forced to struggle with alone – attention to which ultimately ensures benefits in better work and fewer problems for the employer. Educators can help all parties name these issues, critically analysing their sources and systemic currents, and finding useful models for negotiating humane, equitable and meaningful work.

Notes

One reviewer of this article requested a definition of this term: ‘gendered work’ refers to the way social and behavioral attributes attaching to one or other sex are embedded in the construction of particular kinds of work and workers.

References

Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gender and Society, 4, 139–158.

Alvesson, M. (2001). Knowledge work: Ambiguity, image, identity. Human Relations, 54(7), 863–886.

Arthur, M. B. & Rousseau, D. M. (2000). The boundaryless career as a new employment principle. In M. B. Arthur & D. M. Rousseau (Eds.), The boundaryless career. New York: Oxford University Press.

Barley, S., & Kunda, G. (2004). Gurus, hired guns and warm bodies: Itinerant experts in a knowledge economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Beckett, D. (2001). Hot action at work: Understanding ‘understanding’ differently. In T. Fenwick (Ed.), Socio-cultural understandings of workplace learning (pp. 73–84). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

Bratton, J., Helms Mills, J., Pyrch, T., & Sawchuk, P. (2004). Workplace learning: A critical introduction. Aurora, Ontario: Garamond.

Brocklehurst, M. (2003). Self and place: a critique of the boundaryless career. Paper presented to the Critical Management Studies Conference. University of Lancaster.

Brewer, A. B. (2000). Work design for flexible work scheduling: Barriers and gender implications. Gender, Gender, Work and Organization, 7(1), 33–49.

Chappell, C., Tennant, M., Soloman, N. & Yates, L. (2003). Reconstructing the lifelong learner: pedagogy and identity in individual, organisational and social change. London: Routledge.

Cohen, L., & Mallon, M. (1999). The transition from organisational employment to portfolio working: Perceptions of boundarylessness. Work, Employment & Society, 13(2), 329–352.

Cope, J., & Watts, G. (2000). Learning by doing – an exploration of experience, critical incidents and reflection in entrepreneurial learning. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research, 6(3), 104–124.

Davis, B., & Sumara, D. J. (2006). Complexity and education: Inquiries into learning, teaching and research. Mahwah, New Jersey: Erlbaum.

Ely, M., Anzul, M., Friedmen, T., Garner, D., & Steinmetz, A. M. (1991). Doing qualitative research: Circles within circles. London: Falmer.

Engeström, Y. (1999). Innovative learning in work teams. In Y. Engeström, R. Miettinen, & R. L. Punamaki (Eds.), Perspectives on activity theory (pp. 377–406), Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14(1), 133–146.

Fenwick, T. (2003). Flexibility and individualisation in adult education careers: The case of portfolio workers. Journal of Education and Work, 16(2), 165–184.

Fenwick, T. (2006). Contradictions in portfolio careers: Work design and client relations. Career Development International, 11(1), 66–79.

Fenwick, T. (2007a). Towards enriched conceptions of work learning: Participation, expansion and translation/mobilization with/in activity. Human Resource Development Review, 5(3), 285–302.

Fenwick, T. (2007b). Knowledge workers in the in-between: Network identities. Journal of Organisational Change Management, 20(4), 509–524.

Gee, J. P. (2000). New people in new worlds: Networks, capitalism and school. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures. London and New York: Routledge.

Gold, M., & Fraser, J. (2002). Managing self-management: Successful transitions to portfolio careers. Work, Employment and Society, 16(4), 579–598.

Hanson, M., & Hagström, T. (2003). The (hidden) curricula of workplace learning: Self-regulation and self-discipline in flexible work settings. Paper presented at the 11th European Congress on Work and Organisational Psychology, Lisboa.

Hoque, K., & Kirkpatrick, I. (2003). Non-standard employment in the management and professional workforce: Training, consultation and gender implications. Work Employment and Society, 17(4), 667–689.

Hughes, K. (1999). Gender and self employment in Canada: assessing trends and policy implications. Canadian Policy Research Network, Ottawa: Renouf Pub.

Industry Canada. (1999). Shattering the glass box: Women entrepreneurs and the knowledge-based economy. Micro-Economic Policy Analysis Branch, retrieved January 2000 from http://strategis.ic.gc.ca/sc_ecnmy/mera/egdoc/o4.htm.

Latour, B. (2005). Re-assembling the social – An introduction to actor network theory. London: Oxford University Press.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (2000). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions and emerging confluences. In N. K. Denzin, & Y.S. Lincon (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mirchandani, K. (2000). ‘The best of both worlds’ and ‘Cutting my own throat’: Contradictory images of home-based work. Qualitative Sociology, 23(2), 159–182.

Mukhtar, S.-M. (1998). Business characteristics of male and female small and medium enterprises in the UK: Implications for gender-based entrepreneurialism and business competence development. British Journal of Management, 9, 41–51.

Probert, B. (1999). Gendered workers and gendered work: Implications for women's learning. In D. Boud & J. Garrick (Eds.), Learning in work (pp. 98–116). London: Routledge.

Simpson, R. (1998). Presenteeism, power and organizational change: Long hours as a career barrier and the impact on the working lives of women managers. British Journal of Management, 9, 37–53.

Statistics Canada. (2000). Women in Canada 2000: A gender based statistical report. Ottawa, Ontario: Statistics Canada.

Storey, J., Salaman, G., & Platman, K. (2005). Living with enterprise in an enterprise economy: freelance and contract workers in the media. Human Relations, 58(8), 1033–1054.

Sullivan, S. E. (1999). The changing nature of careers: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management 25(3), 457–484.

Tietze, S. & Musson, G. (2005). Recasting the home–work relationship: A case of mutual adjustment? Organization Studies,26, 1331–1352.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgements

The study reported in this article was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Fenwick, T. Women’s Learning in Contract Work: Practicing Contradictions in Boundaryless Conditions. Vocations and Learning 1, 11–26 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-007-9003-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-007-9003-9