Abstract

Although coal swelling/shrinking during coal seam gas extraction has been studied for decades, its impacts on the evolution of permeability are still not well understood. This has long been recognized, but no satisfactory solutions have been found. In previous studies, it is normally assumed that the matrix swelling/shrinking strain can be split between the fracture and the bulk coal and that the splitting coefficient remains unchanged during gas sorption. In this study, we defined the fracture strain as a function of permeability change ratio and back-calculated the fracture strains at different states. In the equilibrium state, the gas pressure is steady within the coal; in the non-equilibrium state, the gas pressure changes with time. For equilibrium states, the back-calculated fracture strains are extremely large and may be physically impossible in some case. For non-equilibrium states, two experiments were conducted: one for a natural coal sample and the other for a reconstructed one. For the fractured coal, the evolution of permeability is primarily controlled by the transition of coal fracture strain or permeability from local matrix swelling effect to global effect. For the reconstituted coal, the evolution of pore strain or permeability is primarily controlled by the global effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Coal permeability has been widely studied due to its vital importance for the effective extraction of coal seam gas. Coal is a typical dual porosity/permeability system containing porous matrix surrounded by fractures (Liu et al. 2011a). In the coal matrix, there are a large number of interconnected pores that serve as the storehouse for methane in adsorbed form which can cause coal swelling/shrinkage (Mitra et al. 2011). Coal swelling/shrinkage due to gas adsorption/desorption is a well-known phenomenon (Pan and Connell 2011), which changes the coal cleat apertures (Liu et al. 2011b; Wei et al. 2019a) and plays an important role in the alteration of permeability (Zang et al. 2015; Liu and Harpalani 2013). In some experiments, the permeability variation due to coal swelling/shrinkage may exceed 70% (Pan et al. Pan et al. 2010, Harpalani and Schraufnagel 1990) and even more than 90% (Wei et al. 2019b). Therefore, understanding how to quantitatively describe this influence is crucial for the evaluation of both primary gas production from coal reservoirs and for CO2-enhanced coalbed methane recovery (ECBM) (Bergen et al. 2009b).

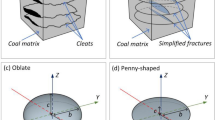

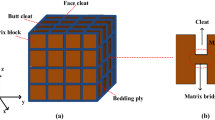

The first reported study of coal-matrix volumetric response to sorption of gas can be traced back to Moffat and Weale (1955). After that, the coal-matrix swelling/shrinkage has been quantified in the laboratory by several researchers (Ottiger et al. 2008; Pini et al. 2009a; Bergen et al. 2009a; Liu and Harpalani 2013). Levine (1996) used a Langmuir-type model to fit the strain data and reservoir pressure. Since then, many permeability models have used the Langmuir equation to represent the bulk sorption strain. In addition, matrix permeability is typically eight orders of magnitude lower than the permeability of the fracture system (Robertson 2005; Gamson et al. 1996). Thus, the permeability depends on its fracture system.

Significant experimental efforts have been made to investigate coal permeability and its evolution (Chen et al. 2013). Based on experimental observations, a variety of coal permeability models have been formulated to define the impact of shrinkage/swelling and match experimental data. In the review of interaction of multiple processes (Liu et al. 2011a), these permeability models are classified into two groups: permeability models under uniaxial strain conditions and permeability models under variable stress conditions.

For uniaxial strain conditions, Gray (1987) firstly attempted to quantify the role of stresses on the evolution of coal–reservoir permeability, and then incorporated swelling/shrinkage effects into the estimation of effective stress by the elastic relation between stress and strain changes within the coal. In this research, it was assumed that reservoir pressure-induced coal-matrix shrinkage is directly proportional to changes in the equivalent sorption pressure. Harpalani and Chen (1997) measured the methane permeability and volumetric strain of a cylindrical specimen under constant effective stress. The results showed that sorption-induced permeability change was linearly proportional to volumetric strain. Seidle and Huitt (1995) assumed matrix swelling and shrinkage are proportional to the amount of gas adsorbed on the coal matrix, not the gas pressure, and that in situ coal deposits can be represented by a matchstick geometry. Under this assumption, a permeability model as a function of sorption-induced volumetric strain was developed, in which simply considered that a change in the length of a matrix block (resulting from swelling or shrinkage) causes an equal, but opposite change in the fracture aperture. Palmer and Mansoori (1996) used the relationship between porosity and pore volume strain and established the permeability evolution model with elastic moduli, initial porosity, sorption isotherm parameters, and pressure drawdown as variable under the assumptions of uniaxial strain and constant overburden stress. Shi and Durucan (2004) followed the research idea that the desorption of methane changes the volumetric strain, the horizontal stress, and the permeability, converted the adsorption expansion strain into the change in effective stress, and established the relationship between permeability and adsorption expansion strain (Gu and Chalaturnyk 2006).

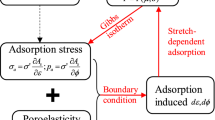

In order to more readily represent the routine conditions for laboratory testing, a series of permeability models under variable stress conditions were established. Zhang et al. (2008) developed an effective strain-based coal permeability model, which can be applied to any boundary conditions. In this article, it was assumed that the sorption-induced matrix strain is the same as the sorption-induced fracture strain. Connell et al. (2010) distinguished the sorption strain of the coal matrix, the pores (or the cleats) and the bulk coal and derived several different forms of permeability models for the laboratory tests (Liu et al. 2018; Cui et al. 2018). However, the fracture strain and the matrix strain are more difficult to measure. Liu et al. (2010) innovatively introduced a new concept of internal swelling stress to consider fracture–matrix interaction during coal deformation processes and concluded that only a fraction of matrix strain resulting from swelling (or shrinkage) contributed to fracture aperture change under certain conditions. A parameter, ƒ, which is the ratio of the strain corresponding to the internal swelling stress to internal swelling strain, was introduced. \(f\) is a constant between zero and one and associated with matrix block connectivity within coal seams. Similarly, Chen et al. (2012) thought only a part of total swelling strain contributes to fracture aperture change and the remaining portion of the swelling strain contributes to coal bulk deformation, and a partition factor is also introduced to estimate this contribution.

As reviewed above, there is a large collection of coal permeability models from empirical ones to theoretical ones. Table 1 shows some representative ones. The key to solve the permeability evolution is to establish the relationship between the adsorption expansion strain and fracture strain. Bulk strain is easy to measure by a strain gauge, while fracture strain is difficult to measure by direct experiments due to its small size and its location in the sample. Therefore, simplified models (such as capillary tubes, matchstick model and cube model) or assumptions are used for quantitative expression of fracture strain. Depending on assumptions, fracture strains can be roughly estimated:

- (1)

Permeability models are developed under uniaxial strain boundary conditions or constant volume boundary conditions (Robertson and Christiansen 2007; Zang et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2012; Liu and Rutqvist 2010). For constant volume boundary conditions, 100% of coal swelling due to the adsorbed gas injection should contribute to the decrease in cleat apertures and coal permeability (Qu et al. 2014). For uniaxial strain conditions, the fracture strain can be calculated based on the evolution of permeability. However, these assumptions may not always be satisfied within the reservoir as discussed by Durucan and Edwards (1986). Furthermore, most of the samples at the laboratory scale are under stress-controlled conditions rather than under constant volume or uniaxial strain conditions (Shi et al. 2018). These assumptions may overestimate the effect of gas sorption on permeability under stress control conditions where the coal sample can expand outward (Robertson and Christiansen 2007; Zang et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2012; Liu and Rutqvist 2010).

- (2)

Permeability models are developed under conditions of variable stress. In these cases, a partition factor is normally introduced (Chen et al. 2012, Liu and Rutqvist 2010). The partition factor is used to estimate the fracture strain. However, there are two drawbacks to this treatment: (1) This approach fails to fully resolve the problem of fracture strain because it does not consider the true matrix–fracture interactions (Zhang et al. 2018). In addition, this value is usually fitted to an optimal solution through the permeability data without considering the influence of external factors; (2) the initial porosity of the cleat is required for the calculation of fracture strains. However, the fracture porosity cannot be directly measured (Shi et al. 2014).

- (3)

It was assumed that the sorption-induced strain for the coal is the same as for the fracture strain (Zhang et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2010, 2011b; Wu et al. 2011). Under this assumption, the adsorption strain will have no effect on the porosity change and permeability evolution, which is not completely consistent with the experimental results.

In this study, we developed fracture strain models to back-calculate the evolution of fracture strain based on the measured permeability data. The back-calculated strains were analyzed both at the equilibrium and non-equilibrium states and discussed their implication on the validity of coal permeability models.

2 Model formulation of fracture strain data

In this section, we first derive a permeability model applicable to any boundary conditions starting from volumetric balance. Then the fracture strain due to matrix adsorption under general conditions is calculated according to the permeability data. Finally, the fracture strain calculation methods are developed under a spectrum of boundary conditions.

2.1 A fracture-strain-based permeability model

The volumetric balance between the volume of bulk rock (Vb), the matrix volume (Vm), and fracture (the cleat for coal in this work) volume (Vf), is \(V_{\text{b}} = V_{\text{m}} + V_{\text{f}}\). The porosity of the rock \(\phi\) is defined as \(\phi = {{V_{\text{f}} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{V_{\text{f}} } {V_{\text{b}} }}} \right. \kern-0pt} {V_{\text{b}} }}\), and can be differentiated,

In Eq. (1), \({\text{d}}\varepsilon_{\text{f}} = {\text{d}}V_{\text{f}} /V_{\text{f}}\) is the fracture strain, \({\text{d}}\varepsilon_{\text{b}} = {\text{d}}V_{\text{b}} /V_{\text{b}}\) is the bulk strain. \(\phi_{ 0}\) is the porosity of the coal at a reference state. Integration of Eq. (1) leads to the following,

Total fracture strain εf and total bulk strain εb can be decomposed into two parts (Connell et al. 2010; Pan and Connell 2012); one that is caused by the mechanistic tractions (denoted by εmb and εmf, respectively) and the other by the gas sorption (denoted by εsb and εsf, respectively), so Eq. (2) can be written as

where εmb and εmf denote the mechanistic strains of rock and fracture, respectively; εsb and εsf are the strains of rock and fracture introduced by matrix swelling due to gas sorption.

The mechanistic strains of rock εmb and mechanistic strains of fracture εmf in Eq. (3) can be expressed as (Zimmerman and Bodvarsson 1996; Pan and Connell 2012).

and

where \(C_{{{\text{b}}\sigma }} = - (\partial V_{\text{b}} /\partial \sigma )_{p} /V_{\text{b}}\), \(C_{{{\text{p}}\sigma }} = - (\partial V_{\text{f}} /\partial \sigma )_{p} /V_{\text{f}}\), σ is the mean stress.

Substituting Eq. (3), Eq. (4) and Eq. (5) into Eq. (2), one obtains

Experiments show that the coal permeability varies with porosity as follows (Wu et al. 2010; Cui and Bustin 2005):

Substituting Eq. (6) into Eq. (7), one obtains

Similarly, if we use the cubic form, Eq. (8) can be written as

When considering the gas diffusion process and the dynamic permeability in the process of gas injection, p in Eq. (9) is a function of time and is labeled p(t), so Eq. (9) can be written as

2.2 A general model of fracture strains

The sorption-induced volumetric strain εsb in Eq. (3) is fitted into Langmuir-type curves and has been verified through experiments (Levine 1996; Pan and Connell 2007). A Langmuir equation used to calculate this volumetric strain εsb is defined as

and

where the Langmuir volumetric strain, εsL, is a constant representing the volumetric strain at infinite pore pressure and the Langmuir pressure constant, pL, representing the pore pressure at which the measured volumetric strain is equal to 0.5εsL.

The fracture strain εsf represents the compression strain of fracture during matrix adsorption and expansion of coal sample, which directly affects the opening change in cleat and plays an important role in permeability evolution. However, it cannot be measured directly. The bulk strain caused by adsorption is usually expansion strain, but the fracture strain is usually compression strain. In order to facilitate the comparison of the two strain values, we define the compressive strain is positive. So Eq. (8) can be written as:

Therefore, we can define a parameter γ, the ratio of fracture strain and bulk strain, which is used to represent the relationship between fracture strain and bulk strain. It is defined as

Substituting Eq. (14) into Eq. (13) leads to

The first term on the right-hand side of Eq. (15) represents the poromechanical effects on permeability, and the second term on the right-hand side of Eq. (15) represents the effects of matrix swelling/shrinking on permeability

Transforming Eq. (13) yields

2.3 Fracture strain models under different boundary conditions

Equations (13), (14) and (15) can be applied to specific boundary conditions. At present, boundary conditions are usually classified into two groups: uniaxial strain boundary conditions and variable stress boundary conditions. Variable stress boundary conditions can be further divided into three cases: constant pore pressure and varying confining pressure (abbreviation for CPP), constant confining pressure and varying pore pressure (abbreviation for CCP), varying confining pressure and varying pore pressure by a constant difference (abbreviation for CES). In this study, we focus on the effect of matrix adsorption expansion on fracture strain.

2.3.1 Fracture strain under constant effective stress conditions

Under CES boundary conditions, since \(\Delta \sigma - \Delta p\text{ = 0}\), Eq. (13) can be simplified:

where kis and k1s, respectively, refer to the core permeability of the i pressure point and the first pressure point, which were measured with adsorbent gas.

As shown in Eq. (17), the change in coal permeability is defined only by the swelling strain, that is why the primary goal of CES tests is to measure the influence of gas adsorption/desorption on the evolution of coal permeability and the associated processes (Shi et al. 2018).

For simplicity, the lowest pressure point of each test with adsorbing gas is selected as the reference point, with the initial pressure as p01 and the initial permeability as k01, and i as the number of the test points. If assuming \(\varepsilon_{\text{sb0}} = \varepsilon_{\text{sf0}} = 0\), then the above equation can be derived

2.3.2 Fracture strain under constant confining pressure conditions

Under CCP boundary conditions, since \(\Delta \sigma \text{ = 0}\), Eq. (13) can be simplified:

As shown in Eq. (20), the coal permeability can change significantly due to the effect of pore pressure changes and sorption strain during adsorbing gas injection (e.g., CH4 and CO2). However, when the non-adsorbing gas (e.g., He and Ar) is injected, the adsorption strain of matrix can be regarded as negligible, and Eq. (20) can be reduced to Eq. (21)

where kins and k1ns, respectively, refer to the core permeability of the i pressure point and the first pressure point, which were measured with non-adsorbing gas.

Comparing Eqs. (20) and (21), the difference of coal permeability between injected adsorbing gas and non-adsorbing gas is caused by matrix strain at the same pore pressure. Therefore, the ratio of Eqs. (20) and (21) can be written as

If the initial conditions are set where the pore pressure in coal is zero, then \(\varepsilon_{{{\text{sb}}0}} = \varepsilon_{{{\text{sf}}0}} = 0\). The εsf can be calculated by

2.3.3 Fracture strain under uniaxial strain conditions

Considering the characteristics of actual reservoir production, Geertsma (1966) holds that the reservoir with high transverse size is mainly deformed in the vertical direction during the production process and it can be approximated by \(\varepsilon_{xx} = \varepsilon_{yy} = 0\). Currently, the commonly used S-D model is based on the assumption of uniaxial strain and the permeability evolution formula is as follows (Shi and Durucan 2004):

Similar to the case of constant confining pressure, permeability is affected by both effective stress change and gas adsorption. When injected with He, Eq. (24) can be simplified:

Therefore, the same treatment method is adopted to obtain the following formula:

2.4 A dynamic fracture strain model

When gas is injected into the sample, gas instantly invades the fractures due to its relatively high permeability and continues to diffuse into the matrix. In the process of dynamic equilibrium of pore pressure, the change in effective stress and the adsorption strain of matrix act on the change in permeability. For injected absorbed gas, we have

For injected non-adsorbing gases, it can be simplified

So, fracture strain can be written as

3 Analysis of fracture strains

At present, a large number of scholars have carried out a series of permeability experiments. In this section, fracture strains are calculated by Eqs. (19), (23), (26) and (29) according to the permeability data and adsorption parameters. These data are derived from published literature or from our own experiments. From these equations, it can be seen that the Langmuir constants and permeability data measured using non-absorbent and absorbent gas of the same coal sample are indispensable.

Some experimental data are tested around 1 MPa to study the influence of gas slip on permeability (Niu et al. 2014; Wang et al. 2019). When the gas pressure is greater than 1 MPa, slip has little effect on permeability. For the sake of simplification, the coupling effects of adsorption expansion and slippage are not considered for the moment, and only the effect of adsorption expansion on permeability is studied. Therefore, the gas injection pressure selected is generally greater than 1 MPa to simplify this problem.

3.1 Calculation of fracture strains under different boundary conditions

3.1.1 Fracture strains of CES tests

Meng and Li (2018) conducted permeability tests on two different rank coals under a fixed effective stress of 3.5 MPa. The properties of coal and experimental details are listed in Table 2. When the pore pressure changes from 1 to 5 MPa (CH4), the permeability of lignite coal and anthracite coal decreased by 57% and 82%, respectively. Fracture strain at CES boundary conditions can be calculated by Eq. (19), and the results are as shown in Fig. 1a. With the increase in pore pressure, the matrix has an obvious compression effect on the fracture and the fracture strain increases.

Relations between the fracture strain and the ratio of fracture strain to bulk strain and its pore pressure using methane at CES boundary conditions (experimental data from Meng and Li 2018). a Fracture strain \(\varepsilon_{\text{sf}}\). b Ratio of fracture strain to bulk strain γ

Figure 1b illustrates the ratio of fracture strain to bulk strain as a function of pore pressure under CES conditions. As the pore pressure increases, the value of γ increases roughly. When the pore pressure changes from 2 to 5 MPa, the value of γ changes from 42.6 to 51.2 for the high-rank coal sample and from 24.5 to 31.3 for the low-rank coal.

The effect of Biot’s coefficient on permeability and fracture strain is worth noting. Pan et al. (2010) conducted the experiment of injecting non-adsorbed gas He under CES boundary conditions. The gas pressure changed from 2 to 10 MPa, and the permeability changed by about 10%. Compared with the permeability change caused by adsorbed gas injected under the same conditions, the permeability change can be completely ignored. Lin and Kovscek (2014) did a similar experiment and came to the conclusion that helium permeability of the core only increased slightly with the increase in pore pressure under constant effective stress. It is shown that the matrix-adsorbed gas plays a major role in permeability evolution under constant effective stress, and when analyzing the fracture strain due to bulk adsorption, the influence of Biot’s coefficient can be ignored.

3.1.2 Fracture strains of CCP tests

We selected the permeability data of using He, N2 and CO2 by Pini et al. (2009b) under a CCP boundary condition of 10 MPa. The properties of coal and experimental details are listed in Table 3. The results show that as the pore pressure varies from 0.93 to 7.42 MPa, the permeability decreases and then increases during CO2 injection. However, the permeability increases during the helium injection. As shown in Fig. 2a, as the pore pressure increases, the fracture strain increases and better conforms to the Langmuir equation. If we choose the pL of the matrix as a parameter to the Langmuir equation, the correlation coefficient of both gases is up to 98%. Figure 2b shows that the magnitude of γ varies between 28 and 29.3 for CO2 and between 104 and 108 for the nitrogen under CCP conditions, respectively.

Relations between the fracture strain and the ratio of fracture strain to bulk strain and its pore pressure at CCP (experimental data from Pini et al. 2009b). a Fracture strain \(\varepsilon_{\text{sf}}\). b Ratio of fracture strain to bulk strain γ

However, the fracture strain calculated according to Wang et al.’s (Wang et al. 2011) data shows a completely different rule and the results of fracture strain are shown in Fig. 3. With the increase in pore pressure, the fracture strain experiences either continuously increases or increases and then decreases. When the second condition occurs, it means that when swelling reaches a certain point, swelling increases cleat aperture and is beneficial to the increase in permeability, which contradicts the previous conclusion that adsorption expansion reduces permeability. This anomaly may be due to that the interaction between the fracture and the matrix was mutated when the adsorption expansion of matrix reaches a certain stage. However, this explanation is just a conjecture that needs to be discussed in future research on this abnormal phenomenon.

Relations between the fracture strain and the ratio of fracture strain to bulk strain and pore pressure at CCP (experimental data from Wang et al. 2011). a Fracture strain \(\varepsilon_{\text{sf}}\). b Ratio of fracture strain to bulk strain γ

3.1.3 Fracture strains of uniaxial strain tests

Feng et al. (2017) conducted permeability tests using He and CH4 under uniaxial strain conditions. The initial reservoir pressure was estimated to be ~ 8.3 MPa, and the vertical and horizontal stresses were estimated at ~ 20.7 and ~ 13.8 MPa. With the flowing gas pressure varying from 1.4 to 8.3 MPa, the permeability using helium keeps increasing and increases by three times, while when methane is injected, the permeability keeps decreasing to 95%. The fracture strains with respect to pore pressure are shown in Fig. 4a. Since only giving pL = 5 MPa without giving specific value of εsL, we assume εsL = 0.01 to calculate γ (Table 4).

Relations between fracture strain and the ratio of fracture strain to bulk strain and pore pressure using methane at uniaxial strain (experimental data from Feng et al. 2017). a Fracture strain \(\varepsilon_{\text{sf}}\). b Ratio of fracture strain to bulk strain γ

It should be noted that the two boundary conditions, uniaxial strain condition and CES condition, were tested with the same coal. Because the permeability data measured in the laboratory are usually in a stress boundary condition while the field data are usually in the uniaxial strain condition, we can further analyze the difference between these two boundary conditions. As the pore pressure increases from 1.4 to 8.3 MPa, the permeability using methane decreases by only 45% under CES boundary conditions, which is significantly less than the decrease under uniaxial strain boundary conditions. As shown in Fig. 4a, the fracture strain under CES is lower than that under uniaxial strain, which indicates that only a fraction of the matrix adsorption strain about 52.8% acted on the compression fracture under CES boundary conditions.

3.2 Evolution of fracture strains during gas injection

When the gas is injected into the coal sample, the original gas equilibrium in the matrix and fracture is broken to attain a new gas pressure equilibrium, which can last for hours or even days at the laboratory scale (Danesh et al. 2017; Liu et al. 2016; Seidle and Huitt 1995). In the process of reaching the new equilibrium, the gas pressure in the cleat reaches equilibrium quickly while the gas pressure and adsorption strain in the matrix constantly change. During this process, the matrix interacts with fractures, and these interactions change permeability and volumetric strain (Liu et al. 2016). Therefore, the volumetric strain evolution characteristics and the permeability evolution characteristics should be continuously measured during the gas injection process.

Researchers normally measured the permeability of coal under the assumption that the adsorption equilibrium state had been reached. Only a few sets of experimental data (Wang et al. 2009, 2010; Liu et al. 2016, Siriwardane et al. 2009) have measured permeability changes throughout the process. Siriwardane et al. (2009) measured the CO2 permeability of Pittsburgh coals under constant confining stress and constant pore pressure conditions by using the pressure transient method. The measured permeability changed notably with the CO2 exposure time, and the permeability variation exhibited an evident kinetic feature. Unfortunately, they did not measure the change in the volumetric strain over time. In this study, we conducted our own experiments to analyze the dynamic evolution process.

3.2.1 Coal core collection and preparation

We selected two different structures of coal samples for the experiment, a natural sample and a reconstituted sample. The natural sample was obtained from the exposed surface of an underground mine located in Henan Province in China. The reconstituted one was made by compressing coal particles from a lump of bituminous coal in Shanxi Province and with a size range of 0.154–0.25 mm. The physical dimensions of the coal cores were both 50 mm in diameter by 100 mm in length.

3.2.2 Experimental apparatus and experimental approach

An unconventional gas (UG) permeability test system was used, as shown in Fig. 5. It primarily consisted of three units: (1) a loading module consisting of a high-pressure chamber, a servo-system, a pressure pump and a temperature control unit; (2) a pore pressure control unit containing a vacuum pump, a cylinder, various pipes and a gas pressure controller; and (3) a data measurement and recording system. Upstream pressure was controlled by an electro-pneumatic actuator connected to a pneumatically actuated regulator. The gas pressure controller had an accuracy of 0.1% of full scale. Pulse decay method was used as coal permeability measuring method due to its shorter test durations compared to steady-state measurements (Yang et al. 2019; Wei et al. 2019b). The volumetric strain was calculated by measuring two axial strain gauges and two radial strain gauges.

Schematic of experimental apparatus for measurement of permeability and volumetric strain (after Wei et al. 2019b)

3.2.3 Experimental procedure

The primary experimental processes are as follows: (1) The coal core was placed in an oven at 45 °C for 12 h before being placed in the core holder. (2) The coal core was installed in the core holder, and a set confining pressure was applied. After that, the sample was placed in a vacuum desiccator for 24 h to remove the residual gas. (3) Methane was injected into the coal, and the upstream pressure was controlled to generate pressure difference between upstream and downstream. In the whole period of experiment, the confining pressure was kept a constant and the temperature was maintained at 20 ± 0.5 °C. The strain at the starting gas injection point was taken as the initial point, and the initial strain was set as 0.

3.2.4 Experimental results and analysis

The experimental data of permeability and volumetric strains are shown in Figs. 6 and 7, respectively. In Fig. 6, the permeability and volumetric strain both varied significantly, although the confining pressure and gas pressure are kept constant in the experiment. When methane is injected, the permeability first increases, then decreases and finally stabilizes as the gas adsorption progresses. Specifically, when the injection time is 2 h, the permeability value is the highest, which is 0.147 mD. Taking the permeability at this time as the reference point, when the injection time is 24 h, the permeability decreases by 32%, and when the injection time is 48 h, the permeability decreases by 54%. When the injection time is nearly 10 days, the permeability tends to stabilize at about 0.031 mD, which is 78.9% lower than the reference point and 53% lower than the 48-h permeability. In comparison, the evolution of permeability using He is totally different and just needs 48 h to reach the stability. For the case of CH4 injection, the volumetric strain increases rapidly with time—decreases slowly—and tends to be stable in 3 days; for the case of He injection, the volumetric strain increases rapidly and tends to be stable in ~ 10 h. Furthermore, when the volumetric strain reaches a stable state, the permeability is still in a rapid decline stage for the case of CH4 injection as shown in Fig. 6. The volumetric strain and permeability changes for the reconstituted coal sample during CH4 and He injections are shown in Fig. 7. For the case of CH4 injection, the volumetric strain rises rapidly and tends to reach the equilibrium after 6 h. Similarly, the volumetric strain also reaches a stable value after 3 h during the helium injection. During the whole process of gas injection, the permeability values of both gases remain relatively stable.

According to Eq. (29), we calculated the fracture strain and γ with respect to the adsorbed time and the calculated results are shown in Fig. 8. The fracture strains of the natural and the reconstituted samples show two different patterns. For the natural sample, the fracture strain decreases rapidly and then increases slowly until it becomes stable. For the reconstituted sample, the fracture strain increases first, then falls and then stabilizes.

As shown in Figs. 6 and 7, the evolutions of permeability for the natural and reconstituted coals are very different. The equilibration time of the reconstituted coal is far less than that of the natural coal. The reason for the difference is that the natural coal behaves as a fractured medium while the reconstituted coal as a porous medium. For a fractured medium, gas instantly invades the fracture because of its relatively high permeability and then diffuses into the coal matrix. As the diffusion progress, the fracture may shrink due to matrix swelling. For a reconstituted coal, gas spreads all over the sample and the whole sample behaves as the coal matrix. The different behavior is illustrated in Fig. 9a, b. For the natural coal, the evolution of permeability is primarily controlled by the transition of coal fracture deformation from local matrix swelling effect to global effect. For the reconstituted coal, the evolution of permeability is primarily controlled by the global effect.

3.3 Influencing factors on the fracture strain

According to previous studies (Tan et al. 2019, Liu et al. 2017), many factors affect coal permeability, including effective stress, pore pressure and gas types. These factors may also affect the fracture strain and the ratio of fracture strain to bulk strain, γ.

3.3.1 Impact of effective stress

In order to illustrate the relationship between effective stress, fracture strain and γ, it is necessary to select permeability data containing different effective stress conditions in the experiment. We take Pan et al.’s (2010) and Wu et al.’s (2017) experimental data as an example. The properties of coal samples and experimental details are listed in Table 5. Wu et al. (2017) measured methane permeability at effective pressures of 1 MPa to 5 MPa in four groups (we select case 3), and Pan et al. (2010) measured the methane permeability at effective pressure of 2, 4 and 6 MPa in one group. The calculated fracture strains and γ are shown in Fig. 10.

Both the fracture strain and the strain ratio should remain unchanged under a constant effective stress. They all should be horizontal lines. Therefore, all changes (deviations from horizontal lines) shown in Fig. 10 are due to gas adsorption-induced swelling. The effect of effective stress on fracture strain may be attributed to two aspects: effect of effective stress on the fracture opening and the effect of matrix–fracture interactions. The increase in effective stress will decrease fracture opening while the matrix–fracture interactions may further narrow and open the fracture opening depending on the gas diffusion area.

3.3.2 Impact of gas characteristics on fracture strain and γ

Studies have been conducted on the adsorption capacity and adsorption strain of coal bulk to different gases (Ottiger et al. 2008; Pini et al. 2009a; Bergen et al. 2009a; Pone et al. 2009). The results show that CO2-induced matrix swelling is larger than the CH4-induced one, while the CH4-induced matrix swelling is larger than the N2-induced one. The helium-induced matrix swellings are negligible. These studies rarely report the influence of gas species on the fracture strain. Figure 3 shows that, at the same pore pressure, the fracture strain caused by CO2 adsorption is larger than that caused by methane adsorption. Similarly, as shown in Fig. 4, Pini et al. (2009b) injected helium, nitrogen and carbon dioxide into core samples, respectively, and found that the fracture strain caused by carbon dioxide adsorption was greater than that caused by nitrogen adsorption. These differences are reflected in the magnitudes of γ from ~ 30 to ~ 105 for different gases.

4 Implications on the validity of coal permeability models

In order to analyze fracture strain data caused by matrix adsorption systematically, the values calculated above are collected in Fig. 11. The horizontal axis represents the ratio of the permeability measured with absorbent gas to the permeability measured with non-absorbent gas under the same conditions. It can be seen clearly that the fracture strain is usually larger than 0.1. This indicates that the actual fracture strain is much larger than the bulk strain. In the previous permeability models, some assumptions related to fracture strain are made to simplify the permeability models, for example assuming that the fracture strain and bulk strain are equal (Zhang et al. 2008; Liu et al. 2010, 2011b; Wu et al. 2011), or strains are infinitesimal (Connell et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2008; Izadi et al. 2011; Chen et al. 2010; Zhang et al. 2018). Obviously, our back-calculated results are not consistent with this fundamental assumption.

As shown in Fig. 3, the maximum fracture strain is 1.1, 1.2 for methane and 1.4, 1.6 for CO2 under CCP conditions of 6 and 12 MPa, respectively. These maximum fracture strains (the compressive fracture strain is positive) are greater than 1. However, the phenomenon of compressive strain exceeding 1 is not realistic and physically impossible. This indicates a contradiction to the assumption of infinitesimal deformation in the derivation of coal permeability models. In permeability models (Zhang et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2012; Connell et al. 2010), the effects of poromechanical effects on the permeability and the effects of matrix swelling/shrinking on the permeability are usually assumed to be separable and investigated individually (Shi et al. 2018). In this assumption, the upper limit of fracture strain is 1 due to the fracture wall cannot interpenetrate each other. However, when gas is injected into a dual-permeability system, the gas pressure in the cleat reaches equilibrium quickly and opens the fractures, and then diffuses into the matrix. The effects of poromechanical response precede the sorption-induced swelling on the change in fracture aperture and permeability, but not simultaneously (Wang et al. 2012). Figures 6 and 8 show the changes in bulk strain and fracture strain with the adsorption time. It can be clearly seen that the natural sample bulk strain tends to be stable on the third day, while the fracture strain needs a longer time (more than 10 days) to reach stability. This reflects that the fracture strain and bulk strain of natural sample are not completely synchronous and the fracture strain lags the bulk strain. The reason for this difference may be that although the bulk strain is potentially small, its impact on the fracture strain or permeability is much more significant.

5 Conclusions

In this study, we defined the fracture strain as a function of permeability change ratio and back-calculated the fracture strains both at the equilibrium and non-equilibrium states. In the equilibrium state, the gas pressure is steady within the coal; in the non-equilibrium state, the gas pressure changes with time. Based on the results of this study, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- (1)

For equilibrium states, our results show that the back-calculated fracture strains are large. In some cases, the fracture strain may be larger than unity. This is physically impossible. This conclusion is not consistent with the assumption of infinitesimal strain in poroelasticity. This inconsistency suggests that the current strain-splitting approach may not be acceptable in permeability models.

- (2)

For non-equilibrium states, both the fracture strain and the bulk strain evolve with time. However, the evolution of fractured (natural) coal is very different from that of intact (reconstituted) coal. For the fractured coal, the evolution of permeability is primarily controlled by the transition of the coal fracture strain or permeability from local matrix swelling effect to global effect. For the reconstituted coal, the evolution of pore strain or permeability is primarily controlled by the global effect. This conclusion suggests that the reconstituted coal samples cannot be used as substitutes of natural ones.

Abbreviations

- b 0 :

-

Initial fracture aperture (m)

- C f :

-

Fracture compressibility (Pa−1)

- C bσ :

-

Bulk compressibility with respect to stress (Pa−1)

- C pσ :

-

Fracture compressibility with respect to stress (Pa−1)

- C m :

-

Compressibility of the matrix (Pa−1)

- E :

-

Young’s modulus of rock (Pa)

- E f :

-

Young’s modulus of fracture (Pa)

- E m :

-

Young’s modulus of matrix (Pa)

- ƒ :

-

A fraction (0–1)

- k :

-

Current permeability of rock (m2)

- k 0 :

-

Initial permeability of rock (m2)

- k is :

-

Permeability of the i pressure point measured with adsorbent gas

- k 1s :

-

Permeability of the first pressure point measured with adsorbent gas

- k ins :

-

Permeability of the i pressure point measured with non-adsorbing gas

- k 1ns :

-

Permeability of the first pressure point measured with non-adsorbing gas

- K :

-

Bulk modulus of rock (Pa)

- K f :

-

Bulk modulus of fracture (Pa)

- K m :

-

Bulk modulus of matrix (Pa)

- K n :

-

Stiffness of void (Pa/m)

- M :

-

Constrained axial modulus (Pa)

- p :

-

Pore pressure (Pa)

- p 0 :

-

Pore pressure at infinite (Pa)

- p f :

-

Pressure in the fracture (Pa)

- p f0 :

-

Initial pressure in the fracture (Pa)

- p m :

-

Pressure in the matrix (Pa)

- p m0 :

-

Initial pressure in the matrix (Pa)

- p L :

-

Langmuir pressure (Pa)

- s :

-

Fracture spacing (m)

- S :

-

The mass of adsorbate per unit volume of coal (kg/m3)

- V b :

-

The volume of bulk rock (m3)

- V f :

-

The volume of fractures (m3)

- V m :

-

The volume of matrix (m3)

- α m :

-

Biot coefficient for matrix

- α f :

-

Biot coefficient for fracture

- γ :

-

The ratio of fracture strain caused by adsorption to the bulk strain caused by adsorption

- ε b :

-

Bulk strain

- ε b0 :

-

Initial bulk strain

- ε f :

-

Fracture strain

- ε f0 :

-

Initial fracture strain

- ε mb :

-

Bulk strain caused by the mechanistic tractions

- ε mf :

-

Fracture strain caused by the mechanistic tractions

- ε sb :

-

Bulk strain caused by adsorption

- ε sb0 :

-

Initial bulk strain caused by adsorption

- ε sf :

-

Fracture strain caused by adsorption

- ε sf0 :

-

Initial fracture strain caused by adsorption

- ε sL :

-

Langmuir volumetric strain

- ε ν :

-

Volumetric strain

- ξ :

-

Volumetric swelling coefficient

- σ :

-

Total stress (Pa)

- σ c :

-

Confining pressure (Pa)

- σ h :

-

Axial pressure (Pa)

- ν :

-

Poisson’s ration of rock

- ϕ 0 :

-

Initial porosity of rock

- ϕ :

-

Porosity of rock

- ϕ f0 :

-

Initial porosity of fracture

References

Bergen F, Spiers C, Floor G, Bots P. Strain development in unconfined coals exposed to CO2, CH4 and Ar: effect of moisture. Int J Coal Geol. 2009a;77:43–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2008.10.003.

Bergen F, Krzystolik P, Wageningen N, Pagnier H, Bartlomiej S. Production of gas from coal seams in the Upper Silesian Coal Basin in Poland in the post-injection period of an ECBM pilot site. Int J Coal Geol. 2009b;77:175–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2008.08.011.

Chen ZW, Liu JS, Elsworth D, Connell LD, Pan ZJ. Impact of CO2 injection and differential deformation on CO2 injectivity under in situ stress conditions. Int J Coal Geol. 2010;81:97–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2009.11.009.

Chen ZW, Liu JS, Pan ZJ, Connell LD, Elsworth D. Influence of the effective stress coefficient and sorption-induced strain on the evolution of coal permeability: model development and analysis. Int J Greenh Gas Control. 2012;8:101–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2012.01.015.

Chen ZW, Liu JS, Elsworth D, Pan ZJ, Wang SG. Roles of coal heterogeneity on evolution of coal permeability under unconstrained boundary conditions. J Nat Gas Sci Eng. 2013;15:38–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2013.09.002.

Connell LD, Lu M, Pan ZJ. An analytical coal permeability model for tri-axial strain and stress conditions. Int J Coal Geol. 2010;84:103–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2010.08.011.

Cui XJ, Bustin RM. Volumetric strain associated with methane desorption and its impact on coalbed gas production from deep coal seams. AAPG Bull. 2005;89:1181–202. https://doi.org/10.1306/05110504114.

Cui GL, Liu JS, Wei MY, Shi R, Elsworth D. Why shale permeability changes under variable effective stresses: new insights. Fuel. 2018;213:55–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2017.10.068.

Danesh N, Chen ZW, Connell LD, Kizil MS, Pan ZJ, Aminossadati SM. Characterisation of creep in coal and its impact on permeability: an experimental study. Int J Coal Geol. 2017;173:200–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2017.03.003.

Durucan S, Edwards JS. The effects of stress and fracturing on permeability of coal. Min Sci Technol. 1986;3:205–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-9031(86)90357-9.

Feng R, Harpalani S, Pandey R. Evaluation of various pulse-decay laboratory permeability measurement techniques for highly stressed Coals. Rock Mech Rock Eng. 2017;50:297–308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-016-1109-7.

Gamson P, Beamish B, Johnson D. Coal microstructure and secondary mineralization: their effect on methane recovery. Geol Soc Lond Spec Pub. 1996;109(1):165–79.

Geertsma J. Problems of rock mechanics in petroleum production engineering. In: 1st Congress of the international society of rock mechanics. 1966.

Gilman A, Beckie R. Flow of coal-bed methane to a gallery. Transp Porous Med. 2000;41:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006754108197.

Gray I. Reservoir engineering in coal seams: part 1-the physical process of gas storage and movement in coal seams. SPE Reserv Eng. 1987;2:28–34. https://doi.org/10.2118/12514-PA.

Gu F, Chalaturnyk RJ. Numerical simulation of stress and strain due to gas sorption/desorption and their effects on in situ permeability of coalbeds. J Can Pet Technol. 2006;45:2247–51. https://doi.org/10.2118/06-10-05.

Guo PK, Cheng YP, Kan J, Li W, Tu QY, Liu HY. Impact of effective stress and matrix deformation on the coal fracture permeability. Transp Porous Med. 2014;103:99–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-014-0289-4.

Harpalani S, Chen G. Influence of gas production induced volumetric strain on permeability of coal. Geotech Geol Eng. 1997;15:303–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00880711.

Harpalani S, Schraufnagel RA. Shrinkage of coal matrix with release of gas and its impact on permeability of coal. Fuel. 1990;69:551–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-2361(90)90137-F.

Izadi G, Wang S, Elsworth D, Liu JS, Wu Y, Pone D. Permeability evolution of fluid-infiltrated coal containing discrete fractures. Int J Coal Geol. 2011;85:202–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2010.10.006.

Levine JR. Model study of the influence of matrix shrinkage on absolute permeability of coal bed reservoirs. Geol Soc Lond Spec Publ. 1996;109:197–212. https://doi.org/10.1144/GSL.SP.1996.109.01.14.

Lin WJ, Kovscek AR. Gas sorption and the consequent volumetric and permeability change of coal I: experimental. Transp Porous Med. 2014;105:371–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-014-0373-9.

Liu SM, Harpalani S. Permeability prediction of coalbed methane reservoirs during primary depletion. Int J Coal Geol. 2013;113:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2013.03.010.

Liu HH, Rutqvist J. A new coal-permeability model: internal swelling stress and fracture-matrix interaction. Transp Porous Med. 2010;82:157–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-009-9442-x.

Liu JS, Chen ZW, Elsworth D, Miao XX, Mao XB. Evaluation of stress-controlled coal swelling processes. Int J Coal Geol. 2010;83:446–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2010.06.005.

Liu JS, Chen ZW, Elsworth D, Qu HY, Chen D. Interactions of multiple processes during CBM extraction: a critical review. Int J Coal Geol. 2011a;87:175–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2011.06.004.

Liu JS, Chen ZW, Elsworth D, Miao XX, Mao XB. Evolution of coal permeability from stress-controlled to displacement-controlled swelling conditions. Fuel. 2011b;90:2987–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2011.04.032.

Liu QQ, Cheng YP, Zhou HX, Guo PK, An FH, Chen HD. A mathematical model of coupled gas flow and coal deformation with gas diffusion and klinkenberg effects. Rock Mech Rock Eng. 2014;48:1163–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00603-014-0594-9.

Liu QQ, Cheng YP, Ren T. Experimental observations of matrix swelling area propagation on permeability evolution using natural and reconstituted samples. J Nat Gas Sci Eng. 2016;34:680–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2016.07.035.

Liu T, Lin BQ, Yang W. Impact of matrix–fracture interactions on coal permeability: model development and analysis. Fuel. 2017;207:522–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2017.06.125.

Liu XX, Sheng JC, Liu JS, Hu YJ. Evolution of coal permeability during gas injection—from initial to ultimate equilibrium. Energies. 2018;11:2800. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11102800.

Lu SQ, Cheng YP, Li W. Model development and analysis of the evolution of coal permeability under different boundary conditions. J Nat Gas Sci Eng. 2016;31:129–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2016.02.049.

Meng Y, Li ZP. Experimental comparisons of gas adsorption, sorption induced strain, diffusivity and permeability for low and high rank coals. Fuel. 2018;234:914–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2018.07.141.

Mitra A, Harpalani S, Liu SM. Laboratory measurement and modeling of coal permeability with continued methane production: part 1—laboratory results. Fuel. 2011;94:110–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2011.10.052.

Moffat DH, Weale KE. Sorption by coal of methane at high-pressures. Fuel. 1955;34:449–62.

Niu SW, Zhao YS, Hu YQ. Experimental investigation of the temperature and pore pressure effect on permeability of lignite under the in situ condition. Transp Porous Med. 2014;101:137–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-013-0236-9.

Ottiger S, Pini R, Storti G, Mazzotti M. Competitive adsorption equilibria of CO2 and CH4 on a dry coal. Adsorption. 2008;14:539–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10450-008-9114-0.

Palmer I, Mansoori J. How permeability depends on stress and pore pressure in coalbeds: a new model. In: SPE annual technical conference and exhibition. Soc Pet Eng. 1996. https://doi.org/10.2118/52607-pa.

Pan ZJ, Connell LD. A theoretical model for gas adsorption-induced coal swelling. Int J Coal Geol. 2007;69:243–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2006.04.006.

Pan ZJ, Connell LD. Modelling of anisotropic coal swelling and its impact on permeability behaviour for primary and enhanced coalbed methane recovery. Int J Coal Geol. 2011;85:257–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2010.12.003.

Pan ZJ, Connell LD. Modelling permeability for coal reservoirs: a review of analytical models and testing data. Int J Coal Geol. 2012;92:1–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2010.12.003.

Pan ZJ, Connell LD, Camilleri M. Laboratory characterisation of coal reservoir permeability for primary and enhanced coalbed methane recovery. Int J Coal Geol. 2010;82:252–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2009.10.019.

Pini R, Ottiger S, Burlini L, Storti G, Mazzotti M. CO2 storage through ECBM recovery: an experimental and modeling study. Energy Procedia. 2009a;1:1711–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2009.01.224.

Pini R, Ottiger S, Burlini L, Storti G, Mazzotti M. Role of adsorption and swelling on the dynamics of gas injection in coal. J Geophys Res Solid Earth. 2009b. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008JB005961.

Pone J, Halleck PM, Mathews J. Sorption capacity and sorption kinetic measurements of CO2 and CH4 in confined and unconfined bituminous Coal. Energy Fuels. 2009;23:4688–95. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef9003158.

Qiang M, Harpalani S, Liu SM. A simplified permeability model for coalbed methane reservoirs based on matchstick strain and constant volume theory. Int J Coal Geol. 2011;85:43–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2010.09.007.

Qu HY, Liu JS, Pan ZJ, Connell LD. Impact of matrix swelling area propagation on the evolution of coal permeability under coupled multiple processes. J Nat Gas Sci Eng. 2014;18:451–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2014.04.007.

Robertson EP. Measurement and modeling of sorption-induced strain and permeability changes in coal. Golden: Colorado School of Mines, Arthur Lakes Library; 2005.

Robertson EP, Christiansen RL. Modeling laboratory permeability in coal using sorption-induced strain data. SPE Reserv Eval Eng. 2007;10(03):260–9. https://doi.org/10.2118/97068-PA.

Robertson EP, Christiansen RL. A permeability model for coal and other fractured, sorptive-elastic media. In: SPE Eastern regional meeting. Society of petroleum engineers, 2006. https://doi.org/10.2118/104380-MS.

Seidle JR, Huitt L. Experimental measurement of coal matrix shrinkage due to gas desorption and implications for cleat permeability increases. In: International meeting on petroleum Engineering. Society of petroleum engineers, 1995. https://doi.org/10.2118/30010-MS.

Shi JQ, Durucan S. Drawdown induced changes in permeability of coalbeds: a new interpretation of the reservoir response to primary recovery. Transp Porous Med. 2004;56(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:TIPM.0000018398.19928.5a.

Shi JQ, Durucan S, Shimada S. How gas adsorption and swelling affects permeability of coal: a new modelling approach for analysing laboratory test data. Int J Coal Geol. 2014;128–129:134–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2014.04.012.

Shi R, Liu JS, Wei MY, Elsworth D, Wang XM. Mechanistic analysis of coal permeability evolution data under stress-controlled conditions. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci. 2018;110:36–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2018.07.003.

Siriwardane H, Haljasmaa I, McLendon R, Irdi G, Soong Y, Bromhal G. Influence of carbon dioxide on coal permeability determined by pressure transient methods. Int J Coal Geol. 2009;77:109–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2008.08.006.

Tan YL, Pan ZJ, Feng XT, Zhang DX, Connell LD, Li SJ. Laboratory characterisation of fracture compressibility for coal and shale gas reservoir rocks: a review. Int J Coal Geol. 2019;204:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2019.01.010.

Wang GX, Massarotto P, Rudolph V. An improved permeability model of coal for coalbed methane recovery and CO2 geosequestration. Int J Coal Geol. 2009;77:127–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2008.10.007.

Wang GX, Wei XR, Wang K, Massarotto P, Rudolph V. Sorption-induced swelling/shrinkage and permeability of coal under stressed adsorption/desorption conditions. Int J Coal Geol. 2010;83:46–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2010.03.001.

Wang SG, Elsworth D, Liu JS. Permeability evolution in fractured coal: the roles of fracture geometry and water-content. Int J Coal Geol. 2011;87:13–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2011.04.009.

Wang SG, Elsworth D, Liu JS. A mechanistic model for permeability evolution in fractured sorbing media. J Geophys Res Solid Earth. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011JB008855.

Wang LS, Chen ZW, Wang CG, Elsworth D, Liu WT. Reassessment of coal permeability evolution using steady-state flow methods: the role of flow regime transition. Int J Coal Geol. 2019;211:103210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2019.103210.

Wei MY, Liu JS, Elsworth D, Li SJ, Zhou FB. Influence of gas adsorption induced non-uniform deformation on the evolution of coal permeability. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci. 2019a;114:71–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2018.12.021.

Wei MY, Liu JS, Shi R, Elsworth D, Liu ZH. Long-term evolution of coal permeability under effective stresses gap between matrix and fracture during CO2 injection. Transp Porous Med. 2019b;130(3):969–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11242-019-01350-7.

Wu Y, Liu JS, Elsworth D, Chen ZW, Connell LD, Pan ZJ. Dual poroelastic response of a coal seam to CO2 injection. Int J Greenh Gas Control. 2010;4:668–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2010.02.004.

Wu Y, Liu JS, Elsworth D, Siriwardane H, Miao XX. Evolution of coal permeability: contribution of heterogeneous swelling processes. Int J Coal Geol. 2011;88:152–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2011.09.002.

Wu YT, Pan ZJ, Zhang DY, Down DI, Lu ZH, Connell LD. Experimental study of permeability behaviour for proppant supported coal fracture. J Nat Gas Sci Eng. 2017;51:18–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2017.04.020.

Yang D, Wang W, Chen WZ, Tan XJ, Wang LG. Revisiting the methods for gas permeability measurement in tight porous medium. J Rock Mech Geotech Eng. 2019;11:263–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2018.08.012.

Zang J, Wang K, Zhao YX. Evaluation of gas sorption-induced internal swelling in coal. Fuel. 2015;143:165–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2014.11.007.

Zhang HB, Liu JS, Elsworth D. How sorption-induced matrix deformation affects gas flow in coal seams: a new FE model. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci. 2008;45:1226–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2007.11.007.

Zhang SW, Liu JS, Wei MY, Elsworth D. Coal permeability maps under the influence of multiple coupled processes. Int J Coal Geol. 2018;187:71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coal.2018.01.005.

Zimmerman RW, Bodvarsson GS. Hydraulic conductivity of rock fractures. Transp Porous Med. 1996;23:1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00145263.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the State Key Research Development Program of China (Grant No. 2017YFC0804203), Key Research Program of Frontier Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. QYZDB-SSW-DQC029) and the Australian Research Council under Grant DP200101293. These supports are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Handled by Associate Editor Wai Li

Edited by Yan-Hua Sun

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Liu, J., Pan, P. et al. Evolution and analysis of gas sorption-induced coal fracture strain data. Pet. Sci. 17, 376–392 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-019-00422-z

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-019-00422-z