Abstract

A new type of photocatalytic La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− layered double hydroxide (LDH) material (molar ratio, La/Zn/Al = 1:7:2) was prepared by a complexing agent-assisted homogeneous precipitation technique. The structure of the prepared LDH material was systematically studied. Under UV irradiation, the desulfurization efficiency of the LDH material was 87% in 2 h. For La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH material, the introduction of MoO42− increased the interlayer space for promoting the adsorption of benzothiophene (BT), and MoO42− might provide active sites for the oxidation of BT, resulting in the high desulfurization efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years, sulfur compounds produced in the production and use of fuel have gradually become one of the main pollutants which affect air quality. Sulfur compounds mainly exist in diesel oil in the form of derivatives of thiophene and benzothiophene (BT). Therefore, it is an important issue to reduce the content of sulfur-containing compounds such as thiophene, benzothiophene, dibenzothiophene (DBT) and 4,6-dimethyldibenzothiophene (DMDBT) to very low levels to prevent air pollution during the combustion of commercial diesel or gasoline (Fallah et al. 2014).

Various methods such as adsorption desulfurization (ADS) (Fallah and Azizian 2012; Wang et al. 2011; Miao et al. 2015), biodesulfurization (BDS) (Ismi et al. 2017; Paixão et al. 2016), extraction desulfurization (EDS) (Yu et al. 2017) and oxidative desulfurization (ODS) (Hao et al. 2017) have been reported. Currently, hydrodesulfurization (HDS) is a conventional method for removal of unwanted sulfur compounds in fuel oil (Muzic et al. 2008; Srivastava 2012). The mechanism of HDS reaction was explained by the destruction of the carbon to sulfur bond utilizing hydrogen with a catalyst to form a sulfur-free hydrocarbon and hydrogen sulfide (Song and Ma 2004; Chen et al. 2010; Qiu et al. 2009). However, HDS has a distinct disadvantage, its inefficiency toward heterocyclic sulfur compounds such as BT (Srivastava 2012; Xiao et al. 2008; Hasan et al. 2012).

In this paper, a new LDH material La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− was prepared and used as a photocatalyst for oxidation decomposition of BT. Hydrotalcite is one of the new types of catalytic materials which have been studied in recent years (Taylor 1973; Zhang and Guo 2016; Ji and Wu 2017; Huang et al. 2017; Li and Wei 2015; Fan and Yang 2013). However, few people studied the desulfurization treatment of diesel with hydrotalcite catalysts. The desulfurization rate, after the oxidation decomposition of BT with the new LDH, reached 87% under UV light for 2 h. La3+ could bring more positive charges to the main layer, and more MoO42− was adsorbed on the surface of the layer, resulting in an increase in the interlayer space which was beneficial for the adsorption of BT on the surface of the layer. MoO42− might provide active sites for the oxidation of BT. So La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDHs catalyst showed high desulfurization efficiency and stability.

2 Experimental

2.1 Preparation of La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO4 2− LDH

The preparation of the La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH was divided into three steps as follows: First, appropriate amounts of La(NO3)3·6H2O, Zn(NO3)2·6H2O, Al(NO3)3·9H2O and urea were weighed and dissolved in 500 mL of deionized water. The La/Zn/Al molar ratio was 1:7:2. Once they were homogenized, the solution was added into a round flask at a constant temperature of 98 °C. After 8 h of reaction, the solution was filtered and washed 2–3 times with standard ethanol to get a white solid. The product was dried overnight in an oven at 60 °C and subsequently ground into powder to obtain a La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–CO32− LDH.

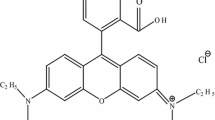

In the second step, La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–CO32− LDH, sodium chloride and concentrated hydrochloric acid were dissolved in the deionized water. After ultrasonic agitation, the volume was fixed at 500 mL and the solution was bubbled with nitrogen for 30 min. The solution was magnetically stirred for 8 h, then filtered, washed and dried at a room temperature to obtain a La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–Cl− LDH.

The prepared La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–Cl− LDH product was added to 200 ml of a 2.5 mol/L Na2MoO4 solution. The resulting solution was heated to 80 °C, treated with nitrogen for 30 min, and finally magnetically stirred for 12 h. The ion exchange products were washed, filtered and dried to obtain La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH material.

2.2 Characterization of catalyst and photocatalytic reaction

The crystal structure of the sample was determined on a SHIMADZU XRD-6000 X ray powder diffractometer with Cu-Kα (λ = 1.5406 Å) at an operating voltage and current of 40 kV and 40 mA, respectively. The SEM images were taken with a Quantum 200 environmental scanning electron microscope operating at an acceleration of 20 kV. The composition and structure of the sample were analyzed on a Bruker FTIR from Germany. The mass ratio of samples to KBr is 1:100. The BET surface area was determined by the multipoint BET method using the adsorption data over a relative pressure (P/P0) range of 0.65–0.95. The pore size distribution was calculated from the desorption branch of the isotherm following the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) method, assuming a cylindrical pore model. UV–Vis diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) were recorded with a UV-2600 Shimadzu spectrophotometer coupled with an integrating sphere (ISR-2600Plus) from 250 to 800 nm to determine the band gap of the materials.

The chemical composition was determined using atomic emission spectrometry in inductively coupled plasma (Agilent ICP-OES 720). In this method, 0.05 g LDH was added into volumetric plastic digestion tubes. Ten milliliters of ultrapure water was added to the tube along with 4 mL 6 mol/L hydrochloric acid. The digestion tubes were uncapped and heated in a hot block for 2 h. The samples were made up to 50 mL with ultrapure water for analysis.

BT, a representative sulfur compound, was used as a solvent in oil and hexane to prepare simulated oil. During the desulfurization experiment, a certain amount of 30% hydrogen peroxide solution, the La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH catalyst and the model oil were added to a quartz tube. Then, the catalyst powder was uniformly dispersed by ultrasound in 1−2 min. After the reaction, the supernatant liquid was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on a Shimadzu HPLC system (Kyoto, Japan) provided with a LC-10AT pump, a SPD-10A UV detector and a manual injector. Subsequently, the tube was exposed under an UV lamp and continued to mix. The rate of desulfurization can be calculated according to the following formula.

where c is the sulfur content in the model oil after desulfurization and c0 is the initial sulfur content of the model oil.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 XRD pattern, FTIR, SEM images and EDS spectra of La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO4 2− LDH

Figure 1a represents the FTIR profiles of the LaZnAl LDH in different anion layers. Once MoO42− was inserted into the interlayer, the stretching vibration peak at 1361 cm−1 corresponding to the CO32− layer of the La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–CO32− LDH material disappeared, and the peak near 1010 cm−1 belonging to MoO42− appeared, revealing that MoO42− ions were successfully inserted into the La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–Cl− LDH layer as is seen in Sect. 2.1.

Figure 1b shows the XRD patterns of two materials. The diffraction peaks of the materials were the same as the characteristic of LDH materials, and no other diffraction peaks corresponding to complex phases were observed, which revealed the purity of the samples. The LDH layer spacing increased from 0.738 nm to 0.982 nm. The (003) diffraction peaks of the La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH material were symmetrical and very intense, indicating that the material with high crystallinity can be prepared by an ion exchange reaction. In addition, the characteristics of diffraction peaks of the crystal material were intense and sharp, which showed that the product had high crystallinity and crystal structure integrity.

Figure 2 shows a noticeable lamellar structure in the SEM image of La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–CO32− LDH, which is similar to that of La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH. So it is unnecessary to show the SEM image of La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH.

From Fig. 3, we can see the EDS spectra of La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–CO32− LDH and La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH. The EDS analysis indicated that La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH consisted mainly of La, Zn, Al and Mo elements, and the La/Zn/Al molar ratio was 1.00:6.73:2.37 (see Table 1), which was close to the actual ratio of 1:7:2. This result showed that Mo element existed in La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH.

3.2 Comparison of activities of La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO 24 and La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–CO3 2− LDHs

Figure 4a, b shows the N2 adsorption isotherms of the La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–CO32− and La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH materials. Both materials showed typical ΙV-shaped N2 absorption isotherms, with small plateaus and hysteresis cycles at high relative pressures. The La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–CO32− and La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH materials were special mesoporous materials. According to the IUPAC definition, this hysteresis loop was of a typical H3 type, which showed the existence of narrow slit channels in the material and the characteristic of LDH materials with a special layered structure. Regarding the BET surface and BJH pore size distribution, the La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–CO32− and La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH materials had surface areas of 93.4 and 186.5 m2/g, respectively. The mean pore sizes of La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–CO32− and La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH materials were found to be 19.6 and 34.2 nm, respectively. The presence of large MoO42− ions inserted into the LDH layers increased the layer spacing, the specific surface area and the pore size.

The UV–Vis DRS of the La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–CO32− and La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDHs are shown in Fig. 5. It can be seen that there was a significant adsorption of both the LDHs in the UV–Vis region. The absorption onset was located at 242 and 322 nm for La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–CO32− LDHs and La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDHs, respectively. The band gap energies of the two LDHs were determined by an established method. The band gap width of La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDHs was about 3.85 eV, 1.27 eV less than that of La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–CO32− LDHs (5.12 eV) using the formula Eg = hc/λ (Eg = 1240/λ) (Nakato et al. 1982).

According to solid energy band theory and the light catalysis mechanism, the smaller the forbidden band width is, the more likely valence electrons are to be excited (Yang et al. 2005; Nakamura et al. 2004). Therefore, it is also suggested that La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDHs had better light absorption activity than La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–CO32− LDHs.

Figure 6a shows the desulfurization rates under different experimental conditions. The desulfurization performance of La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH material was superior to La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–CO32− LDH under UV irradiation. The desulfurization rate of La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH reached 87% in 2 h, which was 2.02 times that of La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–CO32− LDH. We compared the activity of the photocatalyst under UV and visible radiation and found that the desulfurization rate was greater under UV radiation than under visible radiation on the same catalyst. As shown in Fig. 6b, the desulfurization rates of the catalyst La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH were 87%, 86%, 86% and 84% in the recycling experiments. The desulfurization rate of the catalyst slightly decreased, and the desulfurization rate remained above 84%, revealing its excellent activity and stability. Considering the amount of degradation products adsorbed in the LDHs, the desulfurization rate should exceed 94%. The structure of LDH material is relatively stable. The adsorption of MoO42− on the layer surface is stable due to the interlayer confinement. The interlayer space and active sites increased due to the existence of more MoO42−, which was beneficial for the adsorption and oxidation of BT on the surface layer. Therefore, La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH catalyst showed high desulfurization efficiency and stability.

3.3 Investigation of the reaction mechanism

Figure 7 shows the catalytic oxidation of BT on the La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH catalyst. Based on the experimental results and previous work (Li et al. 2015; Zhao et al. 2012; Zhang et al. 2013, 2014; Song et al. 2013), a mechanism (Eqs. 1–7) was proposed and discussed. This mechanism can explain the enhanced photocatalytic activity of the LDH photocatalysts as follows. First, when the La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH molecules absorbed the energy of UV light, photon-generated electrons (e−) and conduction band yielding holes (h+) were generated. Second, photochemical oxidation was carried out, and the hydroxyl radicals were directly produced by hydrogen peroxide. At the same time, the electron hole (h+/e−) reacted with water to produce hydroxyl radicals. On the other hand, the previously generated electrons could directly oxidize the oxygen absorbed on the LDH surface, forming O2− radicals. Finally, the strong oxidized radical (OH− and O2−) generated can oxidize BT to benzothiophene sulfoxide (BTO2).

4 Conclusions

A new complexing agent-assisted homogeneous precipitation technique was successfully developed to synthesize La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH. By comparing the desulfurization effect of two LDHs under UV irradiation, the La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH material had superior desulfurization performance to La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–CO32− LDH. The experimental result indicated that BT was stuck first to the layers of LDH, and then, it was photodecomposed to BTO or BTO2. In conclusion, it was expected that La3+–Zn2+–Al3+–MoO42− LDH has a potential in photocatalysis degradation of organic compounds such as thioether, thiophene, dibenzothiophene and its derivatives.

References

Chen TC, Shen YH, Lee WJ, Lin CC, Wan MW. The study of ultrasound-assisted oxidative desulfurization process applied to the utilization of pyrolysis oil from waste tires. J Clean Prod. 2010;18:1850–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.07.019.

Fallah RN, Azizian S. Removal of thiophenic compounds from liquid fuel by different modified activated carbon cloths. Fuel Process Technol. 2012;93:45–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2011.09.012.

Fallah RN, et al. Effect of aromatics on the adsorption of thiophenic sulfur compounds from model diesel fuel by activated carbon cloth. Fuel Process Technol. 2014;119:278–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2013.11.016.

Fan XM, Yang Z. The electrochemical behaviors of Zn–Al–La-hydrotalcite in Zn–Ni secondary cells. J Power Sources. 2013;241:404–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2013.04.136.

Hao L, Wang M, Deng C, Ren W, Shi Z, Lü H. L-proline-based deep eutectic solvents (DESs) for deep catalytic oxidative desulfurization (ODS) of diesel. J of Hazard Mater. 2017;339:216–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.06.050.

Hasan Z, Jeon J, Jhung SH. Oxidative desulfurization of benzothiophene and thiophene with WOx/ZrO2 catalysts: effect of calcination temperature of catalysts. J Hazard Mater. 2012;205–206:216–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.12.059.

Huang GL, et al. Water–n-BuOH solvothermal synthesis of ZnAl–LDHs with different morphologies and its calcined product in efficient dyes removal. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2017;494:215–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2017.01.079.

Ismi H, Yustin P, Syoni S, Siti KC. Biodesulfurization of organic sulfur in Tondongkura coal from Indonesia by multi-stage bioprocess treatments. Hydrometallurgy. 2017;168:84–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hydromet.2016.10.027.

Ji HS, Wu WH. Enhanced adsorption of bromate from aqueous solutions on ordered mesoporous Mg-Al layered double hydroxides (LDHs). J Hazard Mater. 2017;334:212–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.04.014.

Li CM, Wei M. Recent advances for layered double hydroxides (LDHs) materials as catalysts applied in green aqueous media. Catal Today. 2015;247:163–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cattod.2014.05.032.

Li SW, Li YY, Yang F, Liu Z, Gao RM, Zhao JS. Photocatalytic oxidation desulfurization of model diesel over phthalocyanine/La0.8Ce0.2NiO3. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2015;460:8–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2015.08.030.

Miao G, et al. Selective adsorption of thiophenic compounds from fuel over TiO2/SiO2 under UV-irradiation. J Hazard Mater. 2015;300:426–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.07.027.

Muzic M, Sertic-Bionda K, Gomzi Z. Kinetic and statistical studies of adsorptive desulfurization of diesel fuel on commercial activated carbons. Chem Eng Technol. 2008;31:355–64. https://doi.org/10.1002/ceat.2007.00.341.

Nakamura R, Tanaka T, Nakato Y. Mechanism for visible light responses in anodic photocurrents at n-doped TiO2 film electrodes. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:10617–20. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp048112q.

Nakato Y, Shioji M, Tsubomura H. Photoeffects on the potentials of thin metal films on a n-TiO2 crystal wafer. The mechanism of semiconductor photocatalysts. Chem Phys Lett. 1982;90:453–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/0009-2614(82)80253-4.

Paixão SM, Arez BF, Roseiro JC, Alves L. Simultaneously saccharification and fermentation approach as a tool for enhanced fossil fuels biodesulfurization. J Environ Manag. 2016;182:397–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.07.099.

Qiu JH, Wang GH, Zeng D, Tang Y, Wang M, Li YJ. Oxidative desulfurization of diesel fuel using amphiphilic quaternary ammonium phosphomolybdate catalysts. Fuel Process Technol. 2009;90:1538–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2009.08.001.

Song CS, Ma XL. Ultra-deep desulfurization of liquid hydrocarbon fuels: chemistry and process. Int J Green Energy. 2004;1:167–91. https://doi.org/10.1081/GE-120038751.

Song HY, Gao JJ, Chen XY, He J, Li CX. Catalytic oxidation-extractive desulfurization for model oil using inorganic oxysalts as oxidant and Lewis acid-organic acid mixture as catalyst and extractant. Appl Catal A Gen. 2013;456:67–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcata.2013.02.017.

Srivastava VC. An evaluation of desulfurization technologies for sulfur removal from liquid fuels. RSC Adv. 2012;2:759–83. https://doi.org/10.1039/C1RA00309G.

Taylor HFW. Crystal structures of some double hydroxide minerals. Miner Mag. 1973;39:377–89. https://doi.org/10.1180/minmag.1973.039.304.01.

Wang LT, et al. A theoretical study of thiophenic compounds adsorption on cation-exchanged Y zeolites. Appl Surf Sci. 2011;257:7539–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2011.03.115.

Xiao J, Li Z, Liu B, Xia QB, Yu MX. Adsorption of benzothiophene and dibenzothiophene on ion-impregnated activated carbons and ion-exchanged Y zeolites. Energy Fuels. 2008;22:3858–63. https://doi.org/10.1021/ef800437e.

Yang J, Chen CC, Ji HW, et al. Mechanism of TiO2-assisted photocatalytic degradation of dyes under visible irradiation: photoelectrocatalytic study by TiO2-film electrodes. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:21900–7. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp0540914.

Yu X, Shi M, Yan SQ, Wang H, Wang XH, Yang W. Designation of choline functionalized polyoxometalates as highly active catalysts in aerobic desulfurization on a combined oxidation and extraction procedure. Fuel. 2017;207:13–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2017.06.027.

Zhang SW, et al. In situ synthesis of water-soluble magnetic graphitic carbon nitride photocatalyst and its synergistic catalytic performance. Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5:12735–43. https://doi.org/10.1021/am404123z.

Zhang SW, Li JX, Wang XK, Huang YS, Zeng MY, Xu JZ. In situ ion exchange synthesis of strongly coupled Ag@AgCl/g-C3N4 porous nanosheets as plasmonic photocatalyst for highly efficient visible-light photocatalysis. Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:22116–25. https://doi.org/10.1021/am505528c.

Zhang XL, Guo L. Removal of phosphorus by the core-shell bio-ceramic/Zn-layered double hydroxides (LDHs) composites for municipal wastewater treatment in constructed rapid infiltration system. Water Res. 2016;96:280–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2016.03.063.

Zhao DL, Sheng GD, Chen CL, Wang XK. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue under visible irradiation on graphene@TiO2 dyade structure. Appl Catal. 2012;111–112:303–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2011.10.012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Edited by Xiu-Qin Zhu.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, LG., Li, HX., Song, XL. et al. Degradation of benzothiophene in diesel oil by LaZnAl layered double hydroxide: photocatalytic performance and mechanism. Pet. Sci. 16, 173–179 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-018-0285-3

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-018-0285-3