Abstract

Partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide (HPAM) as the main component of slickwater fracturing fluid is a shear-sensitive polymer, which suffers from mechanical degradation at turbulent flow rates. Five different concentrations of HPAM as well as mixtures of polyacrylamide/xanthan gum were prepared to investigate the possibility of improving shear stability of HPAM. Drag reduction (DR) measurements were performed in a closed flow loop. For HPAM solutions, the extent of DR increased from 30% to 67% with increasing HPAM concentration from 100 to 1000 wppm. All the HPAM solutions suffered from mechanical degradation and loss of DR efficiency over the shearing period. Results indicated that the resistance to shear degradation increased with increasing polymer concentration. DR efficiency of 600 wppm xanthan gum (XG) was 38%, indicating that XG was not as good a drag reducer as HPAM. But with only 6% DR decline, XG solution exhibited a better shear stability compared to HPAM solutions. Mixed HPAM/XG solutions initially exhibited greater DR (40% and 55%) compared to XG, but due to shear degradation, DR% dropped for HPAM/XG solutions. Compared to 200 wppm HPAM solution, addition of XG did not improve the drag reduction efficiency of HPAM/XG mixed solutions though XG slightly improved the resistance against mechanical degradation in HPAM/XG mixed polymer solutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Due to the development of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing technology in recent years, oil and gas production from unconventional resources such as shale formations has played an important role in supplying energy in the USA (Larch et al. 2012; Palisch et al. 2010). Reaching economic rates of hydrocarbon production from shale formations is only possible when micro-fractures are created and connected through effective stimulation treatments such as horizontal fracturing in multiple stages (Loveless et al. 2014; Barati and Liang 2014; Wu et al. 2013).

Creation of openings in the reservoir rock involves pumping fracturing fluids into the wellbore at elevated flow rates and pressures. The viscosity of a fracturing fluid has a remarkable effect on the fracture initiation and the final size of the fracture (Kalgaonkar and Patil 2012). The main component of low-viscosity fracturing fluids is water and low concentrations of polymer ranging from 0.25 to 10 lb per thousand gallons (Bunger et al. 2013; Palisch et al. 2010). In the last decade, an amazing shift from traditional gel-based fracturing fluids toward using slickwater has occurred. Because of the relatively low viscosity of slickwater, cleanup problems and damage associated with using viscous fluids are minimized, which makes slickwater suitable for fracturing low-permeability reservoirs (Wu et al. 2013; Palisch et al. 2010). As a result of lower viscosity, slickwater cannot suspend and transport proppants as effectively as gelled fluids. To overcome poor proppant transport, higher pumping rates are applied, which in turn leads to significant energy loss due to friction and turbulence in the tubular pipeline (Palisch et al. 2010; Kaufman et al. 2008). In order to lower the surface pumping pressures and compensate for the energy losses during pumping, a small amount of high molecular weight polymer is dissolved in the fluid, which acts as a drag reducer. In slickwater treatments, friction reducer is a significant component of the fluid. Long, flexible chain polyacrylamide-based polymers are known to be the most effective drag reduction polymers (Kim et al. 1998).

When a polymer solution is subjected to turbulent flow, the large molecules present in the solution undergo different conformational changes such as flow orientation, stretching, and relaxation. These conformational changes alter the flow field and dynamics of turbulent structures in the vicinity of pipe wall. In the macroscopic scale, those variations result in large drag reduction. However, mechanical degradation of polymer solutions complicates their use (Campolo et al. 2015; Moussa and Tiu 1994). Several theories have been proposed to explain mechanical degradation of polymer solutions, among which extreme stretching of polymer chains and scission of the polymer chain have been most accepted (Rodriguez and Winding 1959). Another study reports that chain scission occurs near the midpoint of the polymer which is caused by the extensional features of the turbulent flow (Lim et al. 2003; Merrill and Horn 1984). Due to the susceptibility of PAM molecules to shear degradation under turbulent flow conditions, researchers have considered other candidates such as rigid polysaccharide molecules to improve the shear stability of drag reducers. Kim et al. used a rotating disk apparatus to verify the DR behavior of 100 wppm XG solutions with four different molecular weights. They observed that XG is more resistant to shear forces than most flexible polymers (Kim et al. 1998). Other researchers compared solutions of polyethylene oxide (PEO), PAM, XG, and guar gum (GG). They observed that synthetic polymers initially induced greater DR efficiency, but as result of mechanical degradation, DR efficiency of synthetic polymers declined more quickly than the polysaccharides. The available data in the literature suggest that XG is shear resistant at turbulent flow conditions, but DR induced by XG is small compared to synthetic polymers such as PAM (Soares et al. 2015; Kulmatova 2013; Wyatt et al. 2011; Kenis 1971). According to the literature, binary solutions of polymers can give rise to DR efficiency and shear stability. Dingilian and Ruckenstein (1974) investigated the DR behavior of PAM, PEO, and carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) single and binary solutions. They observed negative deviation from additivity for binary solutions of two flexible polymer molecules (PEO/PAM) and positive deviation for PAM/CMC and PEO/CMC binary solutions, where flexible and rigid molecules coexist in the solution. Dschagarowa and Bochossian (1978) also observed synergism in the DR behavior of poly-isobutylene and l,4-cis-isoprene rubber binary solutions. They also concluded that flow conditions can affect the degree of deviation from additivity. Malhotra et al. (1988) verified DR of PAM/GG, GG/XG, and PAM/XG binary solutions and concluded that the degree of DR and synergism depend on polymer concentration and flow rate. They also concluded that positive deviation in additivity occurs when both polymers are rigid. But, they mentioned that their conclusions are limited to their experimental conditions and synergism might be observed in many other binary mixtures at higher concentrations. Reddy and Singh (1985) verified the same binary solutions at higher concentrations (C > 200 wppm) and in a larger experimental setup. Contrary to previous authors, they observed negative deviation for PAM/polysaccharide binary solutions. They also verified the shear stability of the polymer solutions and concluded that the solutions showing synergism in DR produce better shear stability (Reddy and Singh 1985). Recently Sandoval and Soares (2016) verified the DR behavior of PAM/XG and PEO/XG binary solutions in a pressure-driven flow loop. The authors reported clear synergism between polymers. They concluded that the improvement observed in the mixed solutions was related to the change in the polymeric conformation from coiled to elongated (Sandoval and Soares 2016). Regarding the DR behavior of binary polymer solutions, very limited work is reported in the literature. On the other hand, the existing published research is limited to certain conditions such as small-scale experimental setups (capillary tube), low flow rates and Reynolds numbers, and certain concentrations or molecular weights. Also, some of the available data contradict each other. As mentioned above, Reddy and Singh (1985) had a different observation from Sandoval and Soares (2016) regarding the DR behavior of PAM/XG binary solution, which we believe arises from the differences in the experimental setup and the molecular weights of the polymers.

In this work, we focus on studying the DR behavior and shear stability of anionic HPAM/XG binary polymer solution. Anionic PAM is the partially hydrolyzed form of polyacrylamide with more flexibility and relatively large molar mass. Both polymers are widely used in industrial applications such as slickwater treatments. There has been little or no work regarding the DR behavior of anionic HPAM and XG mixtures. We believe that it would be interesting to verify the DR behavior of two negatively charged molecules coexisting in a solution. Since various HPAM and XG molecules with different molecular weights are available in the market, we also study the behavior of single polymer solutions, so that we can compare them with binary solutions and assess the degree of improvement in shear stability.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials and preparation

Anionic polyacrylamide as a linear flexible polymer and XG as a semirigid polymer were chosen for this investigation. The molecular weights provided for PAM (Kemira Co.) and XG (PFP Technology) by the vendors are (6–8) × 106 kg mol−1 and (4–5) × 106 kg mol−1, respectively. The accurate values for molar mass were measured using light scattering (for HPAM) and viscometry (for XG) methods. In the light scattering experiments, all solvents were filtered through 0.02 μm cellulose acetate Millipore filters. The HPAM solutions were prepared by dissolution of a known amount of polymer in the 0.5 mol L−1 NaCl solvent. The solutions were filtered through a 0.45 μm cellulose acetate Millipore filters. A concentration range of the polymer solutions (0.2–2.0 g L−1) were analyzed using the batch mode (without size separation) of a multi-angle light scattering (MALS) detector (DAWN-HELEOS II, Wyatt Technology) with a laser wavelength of 658 nm. The specific refractive index increments (dn/dc) value of the HPAM in 0.5 mol L−1 NaCl solution, which was determined by an OPTILAB T-reX differential refractometer (Wyatt Technology) at 633 nm and 25 °C, was 0.162 mL/g. Viscosity averaged molecular weight of XG was measured using the method described in the literature (Sohn et al. 2001). In this method, the intrinsic viscosity [η] was measured with an Ubbelohde capillary viscometer (diameter capillary 0.46 mm, Schott-Gerate), immersed in a water bath maintained at 25.0 ± 0.1 °C. First, the specific viscosity η sp was calculated from the relative viscosity, which is the ratio of the viscosity of xanthan gum solution at a certain concentration to that of the solvent. Each concentration was measured five times. The plot of η sp/C versus C (C is the concentration of solutions) gave a straight line, the intercept of which was [η]. Then, using the Mark–Houwink equation the molar mass was calculated:

The measured values for the molecular weights of the polymers, HPAM and XG, were 7.2 × 106 kg mol−1 and 3.9 × 106 kg mol−1, respectively.

To establish a baseline for further studies, deionized water was used throughout. Using an analytical balance, polymer powders were weighed with an accuracy of ±1 mg (Mettler Toledo XS603s). The preparation of the polymer solutions took place in a separate tank. First, the polymer powders were gradually sprinkled into the solvent and slowly agitated at 30 rpm, in order to prevent particles from clumping on the surface. Then the prepared solutions were stored overnight for complete hydration. The studied concentrations of HPAM solutions were 100, 150, 200, 500, and 1000 wppm. In order to investigate the effect of XG, mixed polymer solutions of 100 wppm HPAM + 100 wppm XG (total C = 200 wppm), 150 wppm HPAM + 100 wppm XG (total C = 250 wppm), and for comparison, 600 wppm XG solutions were prepared.

2.2 Drag reduction and viscosity measurements

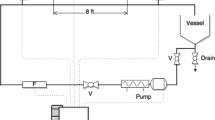

A closed-loop flow system was used for drag reduction and turbulent flow measurements (Fig. 1). The system is comprised of a 60-L supply tank connected to a progressive cavity pump (SEEPEX BN 10-12) with a pumping capacity of 30 GPM (113.56 L/min), and a seamless stainless steel horizontal pipe test section of L = 8 ft. (2.44 m) and inner diameter of 1 in. (2.54 cm). The flow rate of the system was measured using a mass flow meter (OPTIMASS 1000, KROHNE) with an accuracy of ±0.15% and a repeatability of ±0.05% as stated by the manufacturer. The pressure drop data along the measuring length of the pipe were gathered using a membrane differential pressure transducer (PX409, OMEGA). At each flow rate, the Fanning friction factor is calculated by:

Here, f is the Fanning friction factor, ρ is the fluid density, U is the average velocity, ΔP is pressure drop in the measurement length of L, and D is the internal diameter of the pipe.

In the flow experiments, the drag reduction efficiency of the polymer solutions was defined as:

where subscripts “w” and “s” stand for water and polymer solution, respectively, and “Re = const.” signifies the fact that the comparison between the flows is made at the same Reynolds numbers. Here Re = ρUD/η a, and η a is fluid viscosity. In drag reduction experiments, the flow rate was increased stepwise (and kept constant for 1 min at each flow rate), and then, the polymer solutions were sheared in the flow loop at maximum flow of 30 GPM for 2 h and sampling was performed eight times at shearing periods of t = 0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 80, 100, and 120 min. After the shearing process, the flow rate was decreased stepwise in the same manner as it was increased.

Viscosity measurements were carried out in a DHR controlled stress rheometer. The instrument is equipped with a Peltier system to control sample temperature. In our experiments, sample temperature was maintained at 25 ± 0.01 °C. The geometry used in the apparent viscosity measurements was cone and plate. The cone diameter and angle were 60 mm and 2°, respectively. Approximately, 2 mL of the solution was placed between the cone (rotating plate) and the fixed plate and the instrument was set to the strain control mode. In this mode, shear rate (\(\dot{\gamma }\)) was logarithmically increased from 0.01 to 1000 s−1 and shear stress was measured simultaneously, and then, apparent viscosity was calculated using \(\eta_{a} = \sigma /\dot{\gamma }\) correlation, where σ and η a are shear stress and apparent viscosity, respectively. The power-law and Carreau–Yasuda viscosity models were used for fitting the viscosity data.

In the power-law model, n (behavior index) is a measure of deviation from Newtonian behavior and K (consistency index) is a measure of average viscosity. K and n known as power-law parameters were used in friction factor calculations.

In the Carreau–Yasuda equation, η is the shear viscosity, and η 0 and η ∞ are viscosities at zero-shear and infinite-shear plateaus, while λ, n, and a represent the inverse shear rate at the onset of shear thinning, power-law index, and transition index, respectively.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Polyacrylamide solutions

In order to assess the degree of drag reduction and polymer degradation, several samples were taken at specified intervals over the shearing process. Shear stress and apparent viscosity of the samples were measured in the rheometer, and the power-law and Carreau–Yasuda parameters were calculated. For Newtonian fluids, the value of n is 1 and for shear-thinning fluids, such as polymer solutions, n is <1. As the value of n deviates from 1, the degree of non-Newtonian behavior increased. The Carreau–Yasuda and power-law parameters calculated for different concentrations of the anionic polyacrylamide are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 2a, b, respectively. Comparison of power-law parameters of fresh (zero shearing time) HPAM solutions showed that by increasing concentration, values of K increased and n values decreased, indicating increased non-Newtonian behavior. It can also be found that, as the shearing time increased, the values of power-law parameters changed for all the polymer solutions. Figure 2a shows that, over the shearing time, K values of HPAM solutions decreased and n values increased and get close to one (Newtonian behavior). The difference in the n values of the solutions before and after the shearing was large (35%–152% increase for various concentrations). The overall change in n values (after the shearing period) was 35% for a 100 wppm solution, and by increasing concentration, the maximum change in n values (152%) appeared at 200 wppm. As the concentration increased above 200 wppm, n droped to 69% for the 1000 wppm solution. As a result of shear degradation and consequently viscosity reduction, K values declined. By increasing concentration from 100 wppm to 1000 wppm, K values reached a maximum decline of 64% at 200 wppm, but with further concentration increase a 33% decline in K value was found for 1000 wppm HPAM solution.

Another indication of shear degradation is shown in Fig. 3, where the apparent viscosity of the 200 wppm HPAM solution, at shear rates under 10 s−1, undergoes drastic reduction as the circulation time increases. The reason that we only saw changes at lower shear rates might be related to the scission of the molecules that belong to the high tale of the molecular weight distribution of the polymer (Liberatore et al. 2004). Those molecules contributed to the formation of the zero-shear viscosity plateau.

Prandtl–Karman coordinates are a semilog graph of f −½ versus Re.f ½, where f and Re are Fanning friction factor and Reynolds number, respectively. Using Prandtl–Karman coordinates, the degree of DR of polymer solutions can be compared with respect to the boundaries of drag reduction; the onset of drag reduction as the point of departure from Prandtl–Karman law and maximum drag reduction (MDR) or Virk’s asymptote (White and Mungal 2008; Virk 1975). Prandtl–Karman plot for different concentrations of HPAM is shown in Fig. 4. Three flow regimes can be detected:

-

(a)

\(Re\sqrt f < 200\); laminar flow. All polymer solutions obey Poiseuille’s law.

-

(b)

\(200 < Re\sqrt f < 350\); laminar to turbulent transition.

-

(c)

\(Re\sqrt f > 350\); turbulent flow.

It is observed that except for the laminar to turbulent transition region, the turbulent friction factor data for the solutions are bounded in the area between the two universal asymptotes and the data points are linear for all concentrations.

Results of linear fitting of the data points in the turbulent region (Table 2) revealed that by increasing the concentration of polymer, the slope of the lines tended to increase. According to the literature, the slope increment with respect to the Prandtl–Karman law (δ) is proportional to the square root of polymer concentration (\(\delta \propto \sqrt C\)) with a proportionality constant that is the characteristic of the polymer (Virk and Baher 1970). The slope increment values are reported in Table 2. The proportionality constant for the HPAM used in this work is calculated to be 0.27 ± 0.05. Figure 4 shows that by increasing HPAM concentration, the extent of DR increases and the data points approach Virk’s asymptote. Among different concentrations, the extent of DR and slope of data points for 100 wppm HPAM solution were closest to the Prandtl–Karman line (the onset of DR). On the other hand, the greatest DR belongs to the 1000 wppm solution. For solutions with polymer content greater than 200 wppm, in \(200 < Re\sqrt f < 500\) range, the data points were nearly tangential to the MDR line, but by increasing the flow rates (Reynolds number), the data points tended to deviate from MDR. Results indicated that further increase in concentration did not have a large effect on the degree of DR in the experimental conditions of this work.

The effect of polymer concentration and mechanical degradation on the Fanning friction factor of HPAM solutions is shown in Fig. 5a, b, respectively. It can be seen that even at low concentrations of polymer (100 wppm), Fanning friction factor values were much lower than those of water. Increasing polymer concentration resulted in further reduction in friction factors (data points get close to the maximum drag reduction asymptote), and consequently, drag reduction efficiency increased. The smallest values of friction factors at different Reynolds numbers belong to 1000 wppm solution. It was also observed that the difference between turbulent friction factors of 200, 500, and 1000 wppm solutions was very small, which is in agreement with the results shown in Prandtl–Karman coordinates, indicating that at the studied range of Reynolds numbers, DR efficiency was close to its maximum value (MDR); further increase in concentration did not change friction factors. We can also observe that as the Reynolds numbers increased, the data points tended to deviate from MDR.

Shearing had a large impact on reducing the DR ability of polyacrylamide solutions. Comparing the friction factors of 200 wppm HPAM solution at different Reynolds numbers (Fig. 5b) showed a 30%–50% decline after 2 h of shearing. It can be observed that as a result of shearing, friction factor values moved away from MDR line and shifted toward water friction factors at different Reynolds numbers. Although flow rate was constant for all the experiments, a shift in the data points of the sheared samples toward lower Reynolds numbers was observed. The shift was an indication of alteration in the flow regime, which occurred due to the change in the rheological properties of the solutions as a result of shear degradation. Figure 6 shows the changes in the DR% over shearing time for different concentrations of HPAM at constant flow rate. It was observed that, for fresh samples (t = 0), the extent of DR increased from 30% to 67% by increasing polymer concentration from 100 to 1000 wppm. Results also indicated that solutions above 200 wppm produced nearly identical DR at the early stages of shearing (t < 20 min), which corresponds to the results shown in Prandtl–Karman coordinates (Fig. 4). But beyond 20 min, the DR curves tended to diverge, indicating that the degree of shear degradation was different for each polymer concentration. Ptasinski et al. (2003) reported that in flexible polymers such as HPAM, as shear force reached a certain level, the molecules stretch and consequently effective viscosity increased, the turbulent buffer layer thickened, and due to dissipation of the energy from turbulent fluctuations drag was reduced. It is also known that drag is reduced when turbulent flow interacts with polymer networks. When polymer concentration is high enough (above critical overlap concentration, C*), polymer chains are packed closer and begin to interact with each other and form entangled networks (Skelland and Meng 1996).

The decline in the degree of DR was observed at all the concentrations of HPAM solution. Resistance to mechanical degradation over the shearing period is shown in Fig. 7.

Results showed that, as the concentration increased, the resistance to mechanical degradation also increased. This made the 100 wppm solution the least resistant and 1000 wppm solution the most resistant to mechanical degradation. These results agreed with those reported by as Soares et al. (2015), indicating that increasing polymer concentration (PAM or PEO) in the solution could increase the resistance to mechanical degradation. It was also observed that the shear stabilities of 100, 150, 200 wppm solutions were very close and followed the same trends. In other words, 200 ppm solution was only slightly more resistant to degradation (DR t=120/DRmax = 0.5) than 100 wppm solution (DR t=120/DRmax = 0.39). But, above 200 wppm a sudden rise in the shear resistance of the solutions was observed. Both 500 and 1000 wppm solutions showed superior shear stability compared to other solutions. We found that although 200 wppm HPAM solution had similar initial DR% to 500 and 1000 wppm solutions (Fig. 6), it had a larger decline in DR (Fig. 7). The values of DR t=120/DRmax for 500 and 1000 wppm solutions were 0.62 and 0.72 at the end of 2-h shearing period, respectively. It is also interesting to note that the DR/DRmax declined at a slower rate after t = 60 min. For example, the reduction in DR/DRmax value for 1000 wppm solution from t = 60 min to t = 120 min was only 0.06.

From viscosity measurements, the critical overlap concentration (the concentration that marks the beginning of polymer–polymer interaction) of the HPAM solution was determined to be 200 wppm. At C < 200 wppm, there was no polymer network, so there was no decline due to polymer network breakup, but at C > 200 wppm, the networks were more entangled and upon deformation can recover quickly. Also, it seems that at higher concentrations (C > 200 wppm), the extensional force from the turbulent flow was distributed among a larger number of molecules, which resulted in a lower number of chain scissions and higher DR stability. But at C < 200 wppm polymer networks just began to form and were weak. Therefore, at the beginning of the shearing process DR efficiency increased, but gradually as shear forces acted, unstable polymer networks, as well as individual polymer molecules broke up, which resulted in a large decline in the DR efficiency of C < 200 wppm HPAM solutions compared to higher concentrations.

Another result was that the rate of DR decline was fast in the first 60–80 min of the shearing process. This is probably due to the presence of longer chains of polymer in the fresh solutions, which are more susceptible to chain scissions (require less energy to break). After 60 min, the gap between DR lines (Fig. 6) remained nearly constant, which indicated that polymer chains were broken up at a similar rate at all the concentrations.

Several models for correlating the DR behavior of polymer solutions can be found in the literature. Two of the most common models are the exponential decay model (Bello et al. 1996) and Brostow’s model (Brostow 1983). Based on the exponential decay model proposed by Bello et al. (1996), DR follows an exponential decline with time for polyacrylamide and polysaccharide solutions:

where DR% (t) and DR% (0) (or DRmax) are percent drag reduction at times t and t = 0, respectively, and λ is an adjustable parameter. Brostow’s equation is a more general model, which has been applied to various shear degradation applications (Lim et al. 2003) and has been developed to quantitatively describe DR and its changes with time:

Here W is the average number of vulnerability points per chain and h is called rate constant.

The two models were used in this work to correlate the DR data of HPAM and HPAM/XG solutions. Calculated model parameters and goodness of fit (R 2) for both models are reported in Table 3. The solid lines in Fig. 6 represent the fitting results. It can be found that for the studied concentrations of HPAM solution, both models describe the degradation behavior well, though Brostow’s model gives better fits and its predicted values are more accurate.

3.2 HPAM/XG mixed solutions

In order to verify the possibility of stabilizing HPAM with XG, mixed solutions were prepared and sheared in the same manner as the HPAM solutions. Based on the results obtained from the previous section, the DR behavior of binary polymer solutions was compared to that of 200 wppm HPAM solution. Several authors have mentioned that the degree of DR in XG solutions depends on the concentration and molar mass of XG (Soares et al. 2015; Pereira et al. 2013). So higher concentrations of XG are required to reach the same level of DR as HPAM. Our preliminary experiments showed that the DR efficiency of 600 wppm XG was close to the DR values of 200 wppm HPAM.

The Carreau–Yasuda model fitting results of the mixed solutions and a solution containing XG are included in Table 1. Also, friction factors of the mixed polymer solutions and solutions of 600 wppm XG and 200 wppm HPAM are shown in Fig. 8a. It was found that, although polymer concentration in the 600 wppm XG solution was greater than that of 200 wppm HPAM solution, the 600 wppm XG solution possessed greater friction factors. Higher flexibility of HPAM polymer chains with respect to semirigid XG chains resulted in higher energy adsorption (stretching) due to interaction with dynamic turbulent flow and subsequently, superior drag reduction capability of flexible polymers. Also, it was found that in the fresh binary solutions, there is no outstanding synergetic effect between HPAM and XG molecules. Even the 150 wppm HPAM + 100 wppm XG solution, which has a higher total polymer concentration, showed larger friction factors than 200 wppm HPAM.

Figure 8b compares the friction factors of the solutions after 120 min of shearing. Because of high shear stability, XG solution maintained its initial friction reduction efficiency, with a relatively small change in friction factor values. But for the mixed HPAM/XG solutions, the friction factor values largely increased as a result of shearing. It is interesting to note that 200 wppm HPAM solution had a larger increase in its friction factors than mixed solutions (Fig. 8b). This suggested that addition of XG was beneficial in controlling the shear degradation of HPAM. The decline in the DR efficiency and shear resistance of the samples over shearing time is shown in Figs. 9 and 10. Also, as mentioned above, Brostow’s and exponential decay models were used to correlate DR with time (solid lines in Fig. 9; Table 4).

The results indicated that the DR efficiencies of both HPAM and XG binary solutions were smaller than that of 200 wppm HPAM solution, indicating that partially replacing HPAM with XG in the binary solutions had reduced the DR efficiency of the single HPAM solution. Regarding the DR behavior of HPAM/XG binary mixtures, different views can be found in the literature. Sandoval and Soares (2016) recently reported that the DR efficiency of HPAM/XG mixture is close to the DR values of the single HPAM solution at the same total concentration. However, they confirmed that the synergetic effect in PAM/XG mixture is not as notable as PEO/XG. Reddy and Singh (1985) also studied PAM/XG mixtures and reported that the single PAM solution has a higher DR efficiency than a binary mixture. Their data were limited to fresh solutions. We believe that the differences in the reported data might be attributed to the differences in the experimental conditions. In our work, since we were dealing with two negatively charged polymers in the solution, we would expect to obtain different results. We also believed that due to the higher flexibility (higher molecular weight) of the anionic HPAM used in our experiments, HPAM molecules were more susceptible to scission and the interaction between HPAM and XG was reduced. Compared to 600 wppm XG solution, the DR% of 100 wppm HPAM/150 wppm XG solution was high only in the first 60 min of the shearing process and after that, as a result of mechanical degradation the DR values declined. Also, it was found that the 100 wppm HPAM/100 wppm XG solution was less efficient in DR than the 600 wppm XG solution from the beginning till end of the shearing period. Comparison of the shear resistance (DR/DRmax) of the solutions revealed that, as expected, 600 wppm XG solution had the best shear stability among all the solutions and the least decline in DR over the shearing period (0.15 decline in DR/DRmax value). Contrary to XG, 200 wppm HPAM and the binary HPAM/XG solutions suffered from poor shear resistance and a large decline in their DR efficiencies. These results are in agreement with the results reported by Sandoval and Soares (2016). It is interesting to note that the shear resistance of both binary solutions and 200 wppm HPAM solution was nearly identical.

From the obtained friction factor results, it can be inferred that addition of XG reduced the DR capability of mixed solutions (DR% = 40% and 55%) with respect to 200 wppm HPAM solution. Also results suggested that increasing HPAM concentration in the mixed solutions does not change the DR efficiency decline significantly. Since there was only a small amount of chain degradation in semirigid polymers, the extent of DR depended only on the interaction between polymer chains and entanglements, which is directly related to polymer concentration. It should be considered that the concentration of XG was 100 wppm for mixed solutions, which is below the critical concentration of XG (C* ≈ 300 ppm). Hence, as suggested by other authors (Wyatt et al. 2011; Berman 1978), mixing HPAM with higher concentrations of XG would be more beneficial in maintaining high DR efficiency and even better control of shear degradation of polyacrylamide solutions, which is the subject of our future work. Same as for the HPAM solutions, Brostow and exponential decay models were used to correlate the drag reduction behavior over time for the HPAM/XG mixed solutions. The result is shown in Fig. 9 and Table 4. It can be found that both models give good fitting, but similar to HPAM solutions, the Brostow’s model correlated the DR reduction data better.

4 Conclusions

The results from this work show that among different concentrations of HPAM, 1000 wppm solution has the highest drag reduction efficiency and the lowest decline in DR%. Increasing the concentration above 200 wppm does not change the DR% of the fresh samples significantly, though increasing concentration increases resistance to mechanical degradation. Results also indicate that mixing flexible HPAM with XG did not improve the degree of DR significantly, but slightly improved the DR stability of HPAM solutions. Since the drag reduction of rigid polymers depends only on concentration, mixing HPAM with higher concentrations of XG might be beneficial in maintaining the DR efficiency of HPAM as well as improving its shear stability. Brostow and exponential decay models were used to correlate the drag reduction decline data. Results indicate that both models can correlate the DR behavior of HPAM, as well as mixed HPAM/XG solutions. Brostow’s model gave slightly better fits.

References

Barati R, Liang J-T. A review of fracturing fluid systems used for hydraulic fracturing of oil and gas wells. J Appl Polym Sci. 2014;131(16). doi:10.1002/app.40735.

Bello JB, Müller AJ, Sáez AE. Effect of intermolecular cross links on drag reduction by polymer solutions. Polym Bull. 1996;36(1):111–8. doi:10.1007/BF00296015.

Berman NS. Drag reduction by polymers. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 1978;10(1):47–64.

Brostow W. Drag reduction and mechanical degradation in polymer solutions in flow. Polymer. 1983;24(5):631–8.

Bunger AP, McLennan J, Jeffrey R. Effective and sustainable hydraulic fracturing. InTech, Janeza Trdine. 2013;9:51000.

Campolo M, Simeoni M, Lapasin R, Soldati A. Turbulent drag reduction by biopolymers in large scale pipes. J Fluids Eng. 2015;137(4):041102.

Dingilian G, Ruckenstein E. Positive and negative deviations from additivity in drag reduction of binary dilute polymer solutions. AIChE J. 1974;20(6):1222–4.

Dschagarowa E, Bochossian T. Drag reduction in polymer mixtures. Rheol Acta. 1978;17(4):426–32.

Kalgaonkar RA, Patil PR. Performance enhancements in metal-crosslinked fracturing fluids. 1 January 2012. SPE: Society of Petroleum Engineers; 2012.

Kaufman PB, Penny GS, Paktinat J. Critical evaluation of additives used in shale slickwater fracs. 1 January 2008. SPE: Society of Petroleum Engineers; 2008.

Kenis PR. Turbulent flow friction reduction effectiveness and hydrodynamic degradation of polysaccharides and synthetic polymers. J Appl Polym Sci. 1971;15(3):607–18.

Kim CA, Choi HJ, Kim CB, Jhon MS. Drag reduction characteristics of polysaccharide xanthan gum. Macromol Rapid Commun. 1998;19(8):419–22. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-3927(19980801)19:8<419:AID-MARC419>3.0.CO;2-0.

Kulmatova D. Turbulent drag reduction by additives. Phys Rev Lett. 2013;84:4765–8.

Larch KL, Aminian K, Ameri S. The impact of multistage fracturing on the production performance of the horizontal wells in shale formations. 1 January 2012. SPE: Society of Petroleum Engineers; 2012.

Liberatore MW, Baik S, McHugh AJ, Hanratty TJ. Turbulent drag reduction of polyacrylamide solutions: effect of degradation on molecular weight distribution. J Nonnewton Fluid Mech. 2004;123(2):175–83.

Lim S, Choi H, Lee S, So J, Chan C. λ-DNA induced turbulent drag reduction and its characteristics. Macromolecules. 2003;36(14):5348–54.

Loveless D, Holtsclaw J, Weaver JD, Ogle JW, Saini RK. Multifunctional boronic acid crosslinker for fracturing fluids. 19 January 2014. IPTC: International Petroleum Technology Conference; 2014.

Malhotra J, Chaturvedi P, Singh R. Drag reduction by polymer–polymer mixtures. J Appl Polym Sci. 1988;36(4):837–58.

Merrill E, Horn A. Scission of macromolecules in dilute solution: extensional and turbulent flows. Polym Commun. 1984;25(5):144–6.

Moussa T, Tiu C. Factors affecting polymer degradation in turbulent pipe flow. Chem Eng Sci. 1994;49(10):1681–92.

Palisch TT, Vincent M, Handren PJ. Slickwater fracturing: food for thought. SPE Prod Oper. 2010;. doi:10.2118/115766-PA.

Pereira AS, Andrade RM, Soares EJ. Drag reduction induced by flexible and rigid molecules in a turbulent flow into a rotating cylindrical double gap device: comparison between Poly (ethylene oxide), Polyacrylamide, and Xanthan Gum. J Nonnewton Fluid Mech. 2013;202:72–87. doi:10.1016/j.jnnfm.2013.09.008.

Ptasinski P, Boersma B, Nieuwstadt F, Hulsen M, Van den Brule B, Hunt J. Turbulent channel flow near maximum drag reduction: simulations, experiments and mechanisms. J Fluid Mech. 2003;490:251–91.

Reddy G, Singh R. Drag reduction effectiveness and shear stability of polymer–polymer and polymer–fibre mixtures in recirculatory turbulent flow of water. Rheol Acta. 1985;24(3):296–311.

Rodriguez F, Winding C. Mechanical degradation of dilute polyisobutylene solutions. Ind Eng Chem. 1959;51(10):1281–4. doi:10.1021/ie50598a034.

Sandoval GA, Soares EJ. Effect of combined polymers on the loss of efficiency caused by mechanical degradation in drag reducing flows through straight tubes. Rheol Acta. 2016;55(7):559–569.

Skelland A, Meng X. The critical concentration at which interaction between polymer molecules begins in dilute solutions. Polym Plast Technol Eng. 1996;35(6):935–45.

Soares EJ, Sandoval GA, Silveira L, Pereira AS, Trevelin R, Thomaz F. Loss of efficiency of polymeric drag reducers induced by high Reynolds number flows in tubes with imposed pressure. Phys Fluids (1994–present). 2015;27(12):125105.

Sohn J-I, Kim C, Choi H, Jhon M. Drag-reduction effectiveness of xanthan gum in a rotating disk apparatus. Carbohydr Polym. 2001;45(1):61–8.

Virk P, Baher H. The effect of polymer concentration on drag reduction. Chem Eng Sci. 1970;25(7):1183–9.

Virk PS. Drag reduction fundamentals. AIChE J. 1975;21(4):625–56. doi:10.1002/aic.690210402.

White CM, Mungal MG. Mechanics and prediction of turbulent drag reduction with polymer additives. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 2008;40:235–56.

Wu Q, Sun Y, Zhang H, Ma Y, Bai B, Wei M. Experimental study of friction reducer flows in microfracture during slickwater fracturing. 8 April 2013. SPE: Society of Petroleum Engineers; 2013.

Wyatt NB, Gunther CM, Liberatore MW. Drag reduction effectiveness of dilute and entangled xanthan in turbulent pipe flow. J Nonnewton Fluid Mech. 2011;166(1–2):25–31. doi:10.1016/j.jnnfm.2010.10.002.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Research Partnership to Secure Energy for America (RPSEA) and Oklahoma State University Chemical Engineering Department for partial support of this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Edited by Xiu-Qin Zhu.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Habibpour, M., Clark, P.E. Drag reduction behavior of hydrolyzed polyacrylamide/xanthan gum mixed polymer solutions. Pet. Sci. 14, 412–423 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-017-0152-7

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12182-017-0152-7