Abstract

Lateral epicondylitis or tennis elbow is a painful and functionally limiting entity affecting the upperextremity and is frequently treated by hand surgeons. Corticosteroid injection is one of the most common interventions for lateral epicondylitis or tennis elbow. Here, a review of the medical literature on this treatment is presented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

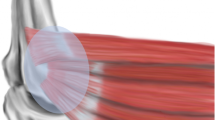

Tennis elbow is a diagnostic term that describes a pattern of pain and localized tenderness at the lateral epicondyle of the distal humerus. The anatomic basis of the injury to the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) origin appears to be multifaceted, involving hypovascular zones, eccentric tendon stresses, and a macroscopic degenerative response. Although many treatments have been advocated, this article discusses the treatment of steroid injection for lateral epicondylitis and documents a review of the medical literature.

Pathology and pathophysiology

Tennis elbow was first described in 1883 by Major [1] as a condition causing lateral elbow pain in tennis players. Over the years, this term has become synonymous with all lateral elbow pain, despite the fact that the condition is most often work-related and many patients who have this condition do not play tennis [2].

It has been estimated, however, that 10–50% of people who regularly play tennis will develop the condition at some time during their careers [3]. A recent study on biomechanics demonstrated that the eccentric contractions of the ECRB muscle during backhand tennis swings, especially in novice players, are the likely cause of repetitive microtrauma that causes tears in the tendon and lateral epicondylitis [4]. Some others suggested causes of tennis elbow, or lateral epicondylitis, are trauma to the lateral region of the elbow, relative hypovascularity of the region [5], and fluoroquinolone antibiotics [6].

Lateral epicondylitis occurs much more frequently than medial-sided elbow pain, with ratios reportedly ranging from 4:1 to 7:1 [7, 8]. In the general population, the incidence is equal among men and women, and in tennis players, male players are more often affected than female players [9].

The disorder occurs more often in the dominant extremity. The average age of the patient who has lateral epicondylitis is 42 years old, with a bimodal distribution among the general population. An acute onset of symptoms occurs more often in young athletes, and chronic, recalcitrant symptoms typically occur in older patients. Although the term epicondylitis implied that inflammation is present, it is in fact only present in the very early stages of the disease.

Treatment: corticosteroid injections

Corticosteroid injection has been historically the most common intervention for lateral epicondylitis. This intervention must be compared to the efficacy of a “wait-and-see” policy because the disorder is most often self-limited.

Smidt et al. [10] reviewed 13 randomized, controlled trials that evaluated the effects of corticosteroid injections compared to placebo injection, injection with local anesthetic and injection with dexamethasone and triamcinolone. Although the evaluated evidence showed superior short-term effects of corticosteroid injections for lateral epicondylitis in terms of pain relief and grip strength, no beneficial effects were found for intermediate- or long-term follow-up [10].

Among prospective, randomized trials controlled with a placebo injection, none showed a difference at final evaluation.

Altay et al. [11] compared 60 patients treated with 2 ml lidocaine to 60 patients treated with 1 ml lidocaine combined with 1 ml triamcinolone, with all injections performed with a peppering technique of 40–50 injections. Another trial compared disabilities of the arm, shoulder, and hand score, grip, and pain in 31 patients injected with lidocaine and dexamethasone and 33 patients injected with lidocaine only [12]. A third trial randomized 19 subjects to receive rehabilitation and a sham injection, and 20 to receive rehabilitation and a corticosteroid injection [13]. There was no significant difference between the two groups on a pain questionnaire, a visual analog pain scale, and a grip measurement at 4, 8, and 24 weeks (P < 0.05). Both groups improved significantly over time, with more than 80% of subjects reporting improvements from baseline to 6 months (P < 0.5) [13].

Bisset et al. [14] in Australia and Smidt et al. [15] in the Netherlands randomized patients with tennis elbow to physiotherapy, corticosteroid injection, or a “wait-and-see” approach. In both studies, corticosteroid injection showed significantly better effects at 6 weeks (P < 0.01) but paradoxically high recurrence rates and significantly poorer outcomes at 1 year (P = 0.0001) [15]. In a randomized trial comparing steroid injection to naproxen and placebo tablets, injections were better at 4 weeks, but over 80% of patients were better by 52 weeks in all groups with no significant differences (P < 0.05) [16].

In another double-blinded study comparing different kinds of steroid injections to lidocaine alone, Price et al. [17] found that the early response to steroid preparations was significantly better than for lidocaine (P < 0.5), but at 24 weeks, the degrees of improvement were similar. Of interest was the discovery that post-injection worsening of pain occurred in approximately half of all steroid-treated patients [17].

Conclusions

Corticosteroid injection is the corner store of care for lateral epicondylitis. The objective of such conservative care is to relieve pain and reduce inflammation, allowing sufficient rehabilitation and return to activities. Although this treatment has been described as highly successful, there remains a lack of information concerning the long-term outcome of steroid treatment. In conclusion, I believe that a corticosteroid injection runs the risk of delaying resolution of symptoms in the long run.

References

Major HP. Lawn-tennis elbow [letter]. Br Med J. 1883;2:557.

Coonrad RW, Hooper WR. Tennis elbow: its courses, natural history, conservative and surgical management. J Bone Joint Surg. 1973;55:1177–82.

Nirschl RP. Elbow tendinosis/tennis elbow. Clin Sports Med. 1992;11:851–70.

Riek S, et al. A simulation of muscle force and internal kinematics of extensor carpi radialis brevis during backhand tennis stroke: implications for injury. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 1999;14:477–83.

Schneeberger AG, Masquelet AC. Arterial vascularization of the proximal extensor carpi radialis brevis tendon. Clin Orthop. 2002;398:239–44.

LeHuec JC, et al. Epicondylitis after treatment with fluoroquinolone antibiotics. J Bone J Surg Br. 1995;293–5.

Gabel GT, Morrey BF. Tennis elbow. Instr Course Lect. 1998;47:165–72.

Leach RE, Miller JK. Lateral and medial epicondylitis of the elbow. Clin Sports Med. 1987;6:259–72.

Nirschl RP. Soft tissue injuries about the elbow. Clin Sports Med. 1986;5:637–52.

Smidt N, et al. Corticosteroid injections for lateral epicondylitis: a systematic review. Pain. 2002;96:23–40.

Altay T, et al. Local injection treatment for lateral epicondylitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;398:127–30.

Lindenhovius A, et al. Injection of dexamethasone versus placebo for lateral elbow pain: a perspective, double-blind, randomized clinical trial. J Hand Surg. 2008;33A:909–19.

Newcomer KL, et al. Corticosteroid injection in early treatment of lateral epicondylitis. Clin J Sport Med. 2001;11:214–22.

Bisset L, et al. Mobilisation with movement and exercise, corticosteroid injection, or wait and see for tennis elbow: randomised trial. BMJ. 2006;333:939.

Smidt N, et al. Corticosteroid injections, physiotherapy, or a wait-and-see policy for lateral epicondylitis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:657–62.

Hay EM, et al. Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of local corticosteroid injection and naproxen for treatment of lateral epicondylitis of elbow in primary care. BMJ. 1999;319:964–8.

Price R, et al. Local injection treatment of tennis elbow—hydrocortisone, triamcinolone, and lignocaine compared. Br J Rheumatol. 1991;30:39–44.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article has been retracted due to plagiarism.

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12178-012-9114-2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Saccomanni, B. RETRACTED ARTICLE: Corticosteroid injection for tennis elbow or lateral epicondylitis: a review of the literature. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 3, 38–40 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-010-9066-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-010-9066-3