Abstract

Calf strains are common injuries seen in primary care and sports medicine clinics. Differentiating strains of the gastrocnemius or soleus is important for treatment and prognosis. Simple clinical testing can assist in diagnosis and is aided by knowledge of the anatomy and common clinical presentation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Calf strains are a common injury. The “calf muscle” or triceps surae consists of three separate muscles (the gastrocnemius, soleus, and plantaris) whose aponeuroses unite to form the Achilles tendon. The clinical history and physical exam along with imaging studies allow localization of the injured muscle. Differentiating strains in the gastrocnemius and soleus is particularly important for an accurate prognosis, appropriate treatment, and successful prevention of recurrent injury.

Calf strains are generally regarded as common injuries, particularly in athletes, although specific data on injury rates are sparse [1–5]. In one study of soccer players, calf strains represented 3.6% of injuries over a 5-year period [5].

Gastrocnemius strains

Calf strains are most commonly found in the medial head of the gastrocnemius [3]. This injury was first described in 1883 in association with tennis and is commonly called tennis leg [6]. The classic presentation is of a middle-aged male tennis player who suddenly extends the knee with the foot in dorsiflexion, resulting in immediate pain, disability, and swelling. Pain and disability can last months to years depending on the severity and effectiveness of initial treatment [1].

The gastrocnemius is considered at high risk for strains because it crosses two joints (the knee and ankle) and has a high density of type two fast twitch muscle fibers [2, 4, 5, 7]. The combination of biarthrodial architecture leading to excessive stretch and rapid forceful contraction of type two muscle fibers results in strain. This mechanism of injury conjures up the image of a cracking whip. Consequently, strains of the gastrocnemius have historically been called coup de fouet or snap of the whip [6].

Plantaris strains

The plantaris also crosses the knee and ankle joints prior to its common Achilles tendon insertion on the calcaneus. However, the plantaris is considered largely vestigial and rarely involved in calf strains [2, 5]. Isolated strains are difficult to distinguish clinically from strains of the gastrocnemius and can only be identified through imaging [5]. If identified recommended treatment is similar to gastrocnemius strains [5]. As such, this article will group plantaris strains with strains of the gastrocnemius.

Soleus strains

Strains of the soleus vary in reported occurrence from rare to common [3, 5, 8, 9]. Soleus muscle injury may be underreported due to misdiagnosis as thrombophlebitis or lumping of soleus strains with strains of the gastrocnemius [9, 10]. Unlike the gastrocnemius the soleus is considered low risk for injury. It crosses only the ankle and is largely comprised of type one slow twitch muscle fibers. Soleus strains also tend to be less dramatic in clinical presentation and more subacute when compared to injuries of the gastrocnemius. The classic presentation is of calf tightness, stiffness, and pain that worsen over days to weeks. Walking or jogging tends to provoke symptoms [3]. Swelling and disability are generally mild [8].

Differentiating calf muscle strains

Although epidemiology and clinical history can help to distinguish strains of the soleus and gastrocnemius, it is the physical exam that allows us to isolate the site and severity of injury. To localize strains to the gastrocnemius or soleus, a combination of palpation, strength testing, and stretching is required.

Palpation of the calf should occur along the entire length of the muscles and the aponeuroses. It is necessary to identify tenderness, swelling, thickening, defects, and masses if present. Gastrocnemius strains typically present with tenderness in the medial belly or the musculotendinous junction. In soleus strains the pain is often lateral [3]. A palpable defect in the muscle helps in localization and suggests more severe injury.

The origin of the gastrocnemius and soleus are anatomically distinct arising from above and below the knee respectively. This allows the examiner to isolate the activation of the muscles by varying the degree of knee flexion. With the knee in maximal flexion the soleus becomes the primary generator of force in plantar flexion. Conversely with the knee in full extension the gastrocnemius provides the greater contribution [11]. This relationship allows for more accurate strength testing of the individual calf muscles and enables the clinician to better delineate which muscle has been injured.

A similar approach is used to test pain and flexibility with passive ankle movements and stretching. In this case, the knee is again placed in maximal extension and then subsequently in flexion while the ankle is passively dorsiflexed to cause relative isolated stretch of the gastrocnemius and soleus respectively. Use of this technique for clinical isolation of the gastrocnemius and soleus is key to determining the site of injury and guiding rehabilitate stretching and strengthening exercises as described below.

Additional testing that can be used during evaluation of calf strain includes the Thompson test for complete disruption of the Achilles tendon, circumferential calf measurements to quantify asymmetry and functional movements. These movements may include hopping, running, and jumping in order to illicit more sublet calf muscle dysfunction.

It should be noted that concomitant tears of both the soleus and gastrocnemius are possible. This can complicate the clinical picture. Coexisting strains of the gastrocnemius and soleus were found in 17% of calf strains in one radiology study [5].

Although a diagnosis can usually be made on clinical grounds as outlined above, the use of imaging can help if the diagnosis is in doubt. Imaging may also be useful in diagnosis and grading of calf injuries in elite athletes because of unique financial and strategic consequences of return to play decisions [5].

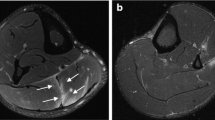

Except in rare situations, MRI and musculoskeletal ultrasound (MSK US) are the two choices for imaging. Both can be used to confirm strain, localize the injured muscle and determine extent of injury. Screening MRI usually consists of T1 and T2 series with occasional addition of fluid sensitive fat suppressed sequences. Contrast agents are not routinely recommended [5, 12].

MSK US is preferred by some institutions and authors [5, 8]. It may be particularly useful when used as part of the initial clinical exam by the sports medicine physician when severe pain and swelling limit clinical testing. Ultrasound may also be valuable in early triage of calf injuries or complaints when a wider differential is in play. Ultrasound has advantages of cost, portability, speed, and ease of use compared to MR when in the hands of an experienced operator.

Grading calf strains

Clinical testing also allows for the grading of calf injuries. All muscle strains are graded 1–3 based on disability, physical finding, and pathologic correlation. Although there is little consistency by authors in the semantics of grading strains, there is consensus on the use of a three-part classification system. This system includes clinical, pathologic, and radiology correlation as noted in the following table [1, 7, 13, 14].

Grade | Symptoms | Signs | Pathologic correlation | Radiology correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Grade 1 1st degree mild | Sharp pain at time of injury or pain with activity. Usually able to continue activity | Mild pain and localized tenderness. Mild spasm and swelling No or minimal loss of strength and ROM | <10% muscle fiber disruption | Bright signal on fluid-sensitive sequences. Feathery appearance <5% muscle fiber involvement |

Grade 2 2nd degree moderate | Unable to continue activity | Clear loss of strength and ROM | >10–50% disruption of muscle fibers | Change in myotendinous junction. Edema and hemorrhage |

Grade 3 3rd degree severe | Immediate severe pain, disability | Complete loss of muscle function Palpable defect or mass. Possible positive Tompson’s test | 50–100% disruption of muscle fibers | Complete disruption of discontinuity of muscle. Extensive edema and hemorrhage. Wavy tendon morphology and retraction |

Treatment for calf strains

Accurate diagnosis and early appropriate treatment can significantly affect duration and amount of disability [1]. Complete recovery of strength and flexibility should be achieved prior to return to pre-injury activity. Premature return may result in a prolonged recovery or incomplete return to pre-injury baseline.

Acute treatment is aimed at limiting hemorrhage and pain, as well as preventing complications. Over the first 3–5 days, muscle rest by limiting stretch and contraction, cryotherapy, compressive wrap or tape, and elevation of the leg are generally recommended [1, 2, 7, 13, 14]. Simple application of an ACE wrap, heel wedge, and crutch-assisted walking would accomplish these goals. Use of NSAIDs should be restricted in the first 24–72 h due to increased bleeding from antiplatelet effects. Celebrex and possibly other COX-2 inhibitors are an option during this period due to their lack of antiplatelet effect [15]. Acetaminophen or narcotic pain medication could also be used. Moist heat and massage early in the healing process are thought to increase the chance of hemorrhage and are generally contra-indicated [13]. Although rare, myositis ossifcans and compartment syndrome can complicate acute strains. If symptoms have not improved as expected with acute treatment, reexamination and consideration for imaging studies should be considered to evaluate for complications or surgical indications.

Following successful acute treatment more active rehabilitation strategies can be started. Rehabilitative exercises should isolate the soleus and gastrocnemius by varying knee flexion as described above. Passive stretching of the injured muscle at this stage helps elongate the maturing intermuscular scar and prepares the muscle for strengthening. As range of motion returns, strengthening should begin with unloaded isometric contraction. Ten days after the injury, the developing scar has the same tensile strength as the adjacent muscle and further progression of rehabilitative exercises can begin. Isometric, isotonic, and then dynamic training exercises can be added in a consecutive manner as each type of exercise is completed without pain [3, 14]. Application of other physical therapy modalities, including massage, ultrasound and electrical stimulation, could also be considered at this stage.

Surgical consultation should be considered for grade III strains (50–100% disruption of muscle) and for cases of prolonged (4–6 months) pain with evidence of contracture. Contractures suggest the presence of painful and restrictive adhesions that may be amenable to surgical intervention. The presence of large intramuscular hematoma may impair clinical progress and is also an indication for surgical referral [14].

References

Coughlin MJ, Mann RA, Saltzman CL. Surgery of the foot and ankle. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2006.

DeLee JC, Drez D Jr, Miller MD, editors. DeLee & Drez’s orthopaedic sports medicine; principles and practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003.

Brukner P, Khan K. Clinical sports medicine. Revised 2nd ed. Australia: McGraw-Hill; 2002.

Garrett WE Jr. Muscle strain injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24(6 suppl):S2–8.

Armfield DR, Kim DH, Towers JD, Bradley JP, Robertson DD. Sports-related muscle injury in the lower extremity. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25:803–42.

Fu FH, Stone DA, editors. Sports injuries: mechanisms, prevention, treatment. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001.

Simon RR, Sherman SC, Koenigsknecht SJ, editors. Emergency orthopedics: the extremities. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2006.

Brukner P. Calf and ankle swelling. Aust Fam Physician. 2000;29(1):35–40.

Cavalier R, Gabos PG, Bowen JR. Isolated rupture of the soleus muscle: a case report. Am J Orthop. 1998;27:755–7.

Lundgren JM, Davis BA. Endartery stenosis of the popliteal artery mimicking gastrocnemius strain: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(9):1548–51.

Bojsen-Moller J, Hansen P, Aagaard P, Svantesson U, Kjaer M, Magnusson SP. Differential displacement of the human soleus and medial gastrocnemius aponeuroses during isometric plantar flexor contractions in vivo. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:1908–14.

Nquyen B, Brandser E, Rubin DA. Pains, strains and fasciculations: lower extremity muscle disorders. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2000;8(2):391–408.

Starkey D, Johnson G, editors. Athletic training and sports medicine. Sudbury: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2006.

Jarvinen TAH, et al. Muscle injuries: biology and treatment. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:745–64.

Leese PT, et al. Effects of celecoxib, a novel cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, on platelet function in healthy adults: a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;40:124–32.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bryan Dixon, J. Gastrocnemius vs. soleus strain: how to differentiate and deal with calf muscle injuries. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2, 74–77 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-009-9045-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-009-9045-8