Abstract

Purpose of Review

To review randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published from 2021–2023 that reported the effects of peer support interventions on outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2DM).

Recent Findings

Literature searches yielded 137 articles and nine RCTs were ultimately reviewed. The reviewed trials involved in-person support groups, peer coach/mentor support, cultural peer support by community health workers, peer support during shared medical appointments (SMAs) including virtual reality-based SMAs, telehealth-facilitated programs, and telephone peer support. Most interventions combined two or more peer support strategies.

Peer support was associated with significant decreases in HbA1c in 6 of the 9 reviewed studies. The largest statistically significant improvements in HbA1c were reported in a study of community health workers in Asia (-2.7% at 12 months) and a Canadian study in which trained volunteer peer coaches with T2DM met with participants once and subsequently made weekly or biweekly phone calls to them (-1.35% at 12 months). Systolic blood pressure was significantly improved in 3 of 9 studies.

Summary

The findings suggest that peer support can be beneficial to glycemic control and blood pressure in T2DM patients. Studies of peer support embedded within SMAs resulted in significant reductions in HbA1c and suggest that linkages between healthcare systems, providers, and peer support programs may enhance T2DM outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Diabetes is one of the fastest growing global health crises and is a major cause of blindness, kidney failure, heart attacks, stroke, lower limb amputation, and mortality [1]. In 2021, approximately 537 million people had diabetes worldwide and the number is projected to reach 643 million by 2030 and 783 million by 2045 [2].

Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) accounts for more than 90% of diabetes cases. Increasing rates are driven by socio-economic, demographic, environmental, and genetic factors [3]. Much of diabetes care needs to be carried out by patients, including monitoring blood glucose, taking medication, getting regular physical activity and maintaining a healthy diet [4••, 5]. Although complications are often preventable through improved metabolic control and implementation of self-care and lifestyle behaviors, patients face numerous self-management barriers [6, 7]. These include inadequate diabetes knowledge, lack of resources for exercise and healthy eating, discomfort from diabetes-related health problems, negative emotions, and lack of social support [8].

Clinical guidelines recommend that individuals with T2DM participate in a lifestyle management program that includes diabetes self-management education and support (DSMES) comprising medical nutrition therapy, physical activity, smoking cessation counseling, and psychosocial care [4••, 9••]. Peer support is not a specified component of DSMES programs, although diabetes education is often conducted in groups of peers with T2DM [10]. The utilization, reach, and effectiveness of DSMES programs can be improved through peer support, which may help to overcome barriers and compensate for limited resources [11]. DSMES programs have proven to be effective in lowering HbA1c, reducing diabetes complications, lowering rates of all-cause mortality, increasing self-efficacy, improving coping skills, and reducing diabetes distress [10].

Ongoing support from family and peers can be beneficial as patients endeavor to implement and sustain the behaviors needed to effectively self-manage T2DM [12]. Peer support has been defined as “the provision of emotional, appraisal and informational assistance by a created social network member who possesses experiential knowledge of a specific behavior or stressor and similar characteristics as the target population”. [13] Peer support typically involves emotional support and informational support. When both peers have diabetes, mutual reciprocity takes place when individuals take turns sharing their personal experiences and providing emotional and informational support to the other person. Through these mechanisms, peer support can improve understanding, motivation, self-efficacy, and mood, and reduce perceived barriers in individuals with T2DM [14]. Diabetes distress, which is the negative emotional experience resulting from the challenge of living with the demands of diabetes, can also be reduced through peer support. [15] A classification of diabetes peer support models based on the work of Heisler [5] is provided in Table 1 titled, Types of Peer Support Models Used in Type 2 Diabetes.

Different types of peers are used across the spectrum of interventions used in diabetes peer support programs. Fellow T2DM patients are peers on the basis of sharing the experience of living with diabetes. Peer support specialists employed by health clinics are peers because they too have been diagnosed with T2DM and live with the condition. Community health workers supporting patients with T2DM are considered to be “cultural peers” because they also live in the same communities, share patients’ racial and ethnic identities and cultural backgrounds, and may have similar life situations including caring for family members with T2DM, although they do not necessarily have a diagnosis of T2DM [16].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, patients with T2DM were at increased risk of severe infections and mortality and many experienced disruptions to their social support networks [12]. These were significant psychological stressors and increased diabetes self-management challenges [11]. The findings of several diabetes peer support interventions conducted during the pandemic are reported in this review.

Peer support interventions have the potential to positively affect outcomes for individuals with T2DM [17•, 18]. Though they have shown promise, the type and overall effectiveness of peer support programs is highly variable. Our purpose was to identify peer support studies to better understand the breadth of strategies used and their relative effectiveness on diabetes self-management and cardiometabolic outcomes.

Methods

PubMed, the Cochrane Library, and the PsycInfo and PsycArticles databases were searched for articles published between January 1, 2021 and December 31, 2023. This timeframe was selected based on T2DM patients’ increased needs for social and emotional support around the time of the COVID-19 pandemic [19, 20]. The included search terms were type 2 diabetes, diabetes mellitus, peer support, social support, support group, self-help group, group support, community support, group education, group visits, and shared medical appointments. Search terms for outcome variables included HbA1c, glycemic control, obesity, body mass index, and weight loss. Studies reporting only survey data or qualitative findings, or that otherwise lacked physiologic outcomes were excluded. Studies of other forms of diabetes (e.g., type 1, gestational) were excluded as were studies of children and non-English language articles.

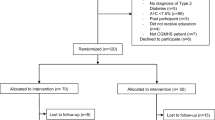

The searches yielded 137 articles for which 129 abstracts were reviewed against inclusion and exclusion criteria, yielding 41 articles that were examined in full text format. After the exclusion of non-RCTs, pilot studies, and studies with incomplete data or low rates of completion, 9 articles were utilized in this review. A flowchart based on PRISMA guidelines is provided in Fig. 1, titled Flow Diagram for Review [21].

Results

Key findings from the review are discussed in this section and are summarized in Table 2 titled, Characteristics and Key Outcomes of Reviewed Studies.

In-Person Peer Support

There is significant evidence for the effectiveness of in-person (IP) support in diabetes education programs [17•, 18, 22]. IP support allows direct verbal and non-verbal communication, enables social interactions and facilitates the exchange of peer-to-peer information, support, and goal setting.

Shared Medical Appointments

Shared medical appointments (SMAs) are typically IP doctor-patient visits in which groups of patients are seen by one or more healthcare providers. Patients interact with both providers and with peers during SMAs [23]. Heisler and colleagues compared the effectiveness of diabetes SMAs to usual care in improving HbA1c [24•]. Patients with T2DM and elevated HbA1c who had been prescribed medication were recruited from 5 U.S. Veterans Affairs (VA) health systems. Participants engaged in IP SMAs of 60–120 min totaling 6–8 h over 12 months where they received education, engaged in goal setting, and shared their experiences with peers. A SMA plus reciprocal peer support intervention arm was available in which participants had the option to be connected to another participant for mutual support, but uptake was low resulting in data being combined with the SMA-only group data. The control group received usual care.

At 6 months, the intervention group’s mean HbA1c was reduced by 0.35% compared to usual care (p = 0.001) and was lower than usual care by 0.53% in participants attending at least half of the sessions (p = 0.001), however, these differences were not significant at 12 months. Insulin starts were significantly greater in the intervention group at both 6 and 12 months. Significant mean differences were not observed for systolic blood pressure, statin starts, or HTN med class changes.

Health Clinic Staff-facilitated Support Groups

Mexico is among countries with the highest prevalence of diabetes, with more than 24% of adults over age 50 being diagnosed with T2DM [25]. The Mexican Ministry of Health’s primary care services include diabetes support groups known as Grupos de Ayuda Mutua (GAM), which provide a supportive group environment, glucose self-monitoring and health information via monthly meetings. Rosales and colleagues sought to complement the GAM program with Meta Salud Diabetes (MSD), a secondary prevention curriculum designed to operate within the framework of the GAM and evaluated its effects on Framingham CVD risk in a cluster-randomized trial [26]. The objective was for the MSD to improve the existing GAM by providing educational information, group discussions, and interactive workshops to promote a healthier diet, increased physical activity and reduced disease complications.

The GAM + MSD intervention consisted of 2-h IP participatory educational sessions and group-based interactive activities facilitated by trained health center staff that engaged GAM support groups at 22 government health clinics over 13 consecutive weeks. The following items were on the agenda at each session: blood pressure and glucose monitoring; readings, discussions and games related to the day’s topic of focus; implementation of a physical activity, and a follow-up goal setting exercise. The usual care group participated in standard GAM support groups.

Mean Framingham CVD risk score was significantly reduced by 3.17% points in the MSD arm versus GAM usual care at 3 months (p = 0.013), however, the between groups difference was not significant at 12 months. Greater reduction in mean Framingham CVD risk was observed in men than women and in those whose HbA1c was < 8% at baseline. No significant effects were observed for HbA1c, blood pressure, or blood lipids. Compared to baseline, diabetes distress in the GAM + MSD group was significantly lower at the 3- and 12-month follow-up assessments.

IP Diet & Lifestyle Intervention with Telephone Support

Sampson and colleagues implemented an IP diet and lifestyle intervention with and without additional telephone support provided by trained peers in the UK for individuals with newly diagnosed “screen detected” type 2 diabetes [27]. Participants were randomized into three arms. Those in the intervention arm (INT) received six 2-h group educational sessions over 12 weeks and up to fifteen 2.5-h group maintenance sessions 8 weeks apart; maximum possible contact time was 49.5 h over 30 months. Individuals randomized to the second arm received the INT intervention plus monthly telephone support from peer volunteers who themselves had T2DM and who had received training as diabetes peer mentors (INT-DPM). Telephone contacts were monthly for 3 months and then every 2 months thereafter for up to 46 months. Those in the control arm (CON) received no intervention.

At 12 months, mean HbA1c significantly decreased in the telephone peer support INT-DPM group compared to the control group (CON) (-0.3%; p = 0.007), however, differences were not significant between the INT-DPM and INT groups, or between the INT and control groups. Days of resistance exercise per week significantly increased compared to the control group in both the INT and INT-DPM groups (INT: 4.22 days, p = 0.01; INT-DPM: 3.32 days, p = 0.02). Glycemic control was significantly lower in INT-DPM group vs. the CON group for participants < 65 years of age compared to those > 65 years (INT-DPM -2.7% vs. CON -2.2%; interaction p = 0.007). No significant differences were observed between any of the groups for body weight, body fat %, or waist circumference.

Family- and Friend-focused Peer Intervention

Positive support by family and friends of individuals with T2DM is strongly associated with more consistent self-care and lower glycemic control [28]. However, it is possible for both helpful and harmful interactions to co-occur within families and friendships. As cultural peers, family members and friends can support or undermine an individual’s diabetes self-care behaviors, which affects the likelihood of them continuing to implement the behaviors [29].

Nelson and colleagues implemented an intervention entitled, Family/friend Activation to Motivate Self-care (FAMS) to assist patients with T2DM in pursuing self-care goals and in effectively responding to both helpful and harmful input from family and friends [30]. In this RCT, FAMS provided monthly health coaching phone calls by behavioral health providers that were subsequently reinforced by text messaging over the 9-month intervention period. Each FAMS participant had the option to designate a cultural peer support person (family member or friend) and invite them to receive the text messages sent by their health coach, potentially prompting peer interactions about the participant’s health behaviors and diabetes self-management goals. Monthly coaching calls to FAMS participants focused on building the following skills: improving the ability to recognize and manage both helpful and harmful messages from friends or family members, SMART goal setting, assertive communication, obtaining social support, collaborative problem-solving, and cognitive behavioral coping skills. Participants in the control group received usual care. Participants and support persons in both study arms received print materials on managing diabetes and providing support to individuals with diabetes, and participants received text messages advising how to access their HbA1c results.

At 6 months, mean HbA1c decreased by 0.25% compared to controls but did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.09). Effects on HbA1c vs. controls were also non-significant at 9 months (-0.05%; p = 0.9) and at 12 months (-0.02%; p = 0.9). Interestingly, participants who were not cohabitating with their support person had significantly lower HbA1c at 6 months (-0.64%; p = 0.033) but not at other time points. The investigators suggested that out-of-home support is likely to strengthen one’s support network, especially for those living alone, and may result in fewer instances of harmful social interactions than can occur with a cohabitating support person. At both 6 and 9 months, significant improvements were observed in intermediate targets of the FAMS intervention compared to controls including diabetes self-efficacy, problem eating behaviors, summative physical activity, helpful family/friend involvement, and autonomy support, although the study did not attempt to measure the relative contributions made by health coaches and cultural peer support persons to these outcomes. Another recent trial of a family and friend cultural peer support intervention for patients with diabetes yielded similar findings, with improvements in intermediate targets but non-significant effects on HbA1c [31].

Peer Coaches and Peer Mentors

Peer Leader Supported Self-Care Intervention

Although large numbers of patients with T2DM receive diabetes care in primary care settings, patients at the highest risk are often managed in subspecialty settings. Tang and colleagues conducted a peer-led intervention for adult T2DM patients presenting to endocrinology and diabetes education centers in British Columbia, Canada [32] and compared it to a usual care control group. Peer leaders completed 30 h of knowledge and skills training in T2DM self-management, providing emotional support, and linking patients to clinical resources. It is important to note that the peer leaders themselves had T2DM and a mean self-reported HbA1c ≤ 8.0% [33]. Individuals in the usual care control group received all services normally available to them at the diabetes education centers, including access to a nurse, dietician and social worker.

Intervention group participants received 30 h of T2DM self-management education and were subsequently matched with a peer leader based on gender and geographic proximity. After an initial IP educational meeting between peer leader and participant, peer leaders made 12 weekly telephone contacts with their partners over the first 3 months of the 48-month intervention to discuss self-management challenges, solve problems, and set self-management goals. During the final 36 weeks, peer leaders made 18 biweekly telephone support calls to intervention group participants.

At 3 months and 12 months post-intervention, HbA1c was not significantly different either from baseline within the intervention group or between the intervention and control groups. Significant between group improvements in systolic blood pressure were observed in the intervention group compared to controls at 12 months (-4.1 points; p = 0.023). Overall distress and emotional distress scores in the intervention group were significantly lower at 3 months and 12 months than at baseline but neither were significantly different than controls at any time point.

Community Health Workers

Community health workers (CHWs) are cultural peers in that they typically share cultural, racial, ethnic, community, and socioeconomic backgrounds with the individuals they serve and they may have direct experience with target health conditions as a patient or in support of a family member [34]. With education and training in diabetes self-management and health behavior change skills, CHWs have the potential to positively affect diabetes outcomes [35].

Home-based Diabetes Education and Counseling by Trained Volunteers

In Nepal, the healthcare system has traditionally focused on communicable diseases rather than chronic conditions and has struggled to adapt to rapidly increasing rates of T2DM [36]. A national initiative to address this need involves the mobilization of more than 50,000 Female Community Health Volunteers (FCHVs) in communities across the country. In this study, these locally-based cultural peers delivered a 12-month IP community-based diabetes intervention to adults in semi-urban settings in Western Nepal with the goal of reducing mean blood glucose [37]. This cluster randomized trial enrolled community residents with a current diagnosis of T2DM or mean blood glucose levels of 126 mg/dL or higher. FCHVs provided home-based diabetes education and counseling, measured blood glucose, blood pressure, height, and weight, and referred patients for clinic visits as needed. Home visits by FCHVs took place once every 4 months (3 visits) for one year. Participants randomized to the control group received usual care in which they managed their T2DM as usual and were placed on a wait list with the option to receive the intervention after 12 months.

Mean fasting blood glucose in the intervention group significantly decreased by 2.7% in the FCHV intervention group while it increased by 2.2% in the usual care group (p < 0.001). Systolic blood pressure significantly decreased (-7.86 points; p = 0.002) in the intervention group vs. controls. Significant improvements were not observed in diastolic blood pressure, physical activity, BMI, alcohol consumption, smoking, fruit and vegetable intake, or medication adherence.

CHW-led Diabetes Education and Support

In a Houston, TX-based study (USA), Spanish-fluent CHWs served as cultural peers to Spanish-speaking low-income Latino(a) adults with T2DM [38]. In the intervention group, CHWs led monthly IP diabetes education group visits for 6 months and engaged in weekly m-Health communication (phone call or text) with study participants. To increase the CHWs’ knowledge of T2DM, they received quarterly diabetes training from physicians via telehealth. Participants randomized to the control group received usual care and placed on a wait list to receive the intervention after 6 months.

At 6 months, mean HbA1c in the intervention group was significantly lower (-0.98%) than controls (p = 0.002) and decreased to a significantly greater extent among intervention group participants with uncontrolled diabetes (-1.31%) compared to control group participants with uncontrolled diabetes (p = 0.007). Mean systolic blood pressure decreased significantly more in the intervention group than control group (-6.89 vs. + 0.03 points; p = 0.023) and the intervention group was also had a significantly greater reduction in mean diastolic blood pressure vs. the control group (-3.36 vs. + 0.2 points; p = 0.046). No significant between group differences were observed for body weight. Significantly more patients in the intervention group started insulin and statin medications compared to controls. Preventive care measures (B12 screening, foot and eye exams, immunizations, urine microalbumin) occurred significantly more often in the intervention group than the control group (p < 0.001).

Peer Coaching Supported DVD Education

The personal stories of peers with T2DM were leveraged in an intervention based on social cognitive theory that aimed to improve medication adherence among low-income African American adults with T2DM [39]. The study took place in a rural Alabama region predominantly populated by African Americans that includes some of the poorest counties in the US, with a prevalence of diabetes of roughly twice the national average [40]. Medical resources are scarce and age-adjusted mortality rates are 39% higher for African Americans compared to the US average. Study participants were taking diabetes oral medications and who reported medication non-adherence or wanted help taking their medications. Peer coaches were community residents who had diabetes or took care of family members with diabetes.

Intervention participants were provided with DVDs that featured diabetes education and personal stories about how community members accepted their diagnosis of T2DM and overcame barriers to medication adherence during a six-month, 11-session behavioral diabetes self-care program delivered by peer coaches over the phone. During a 6-week intensive phase, intervention participants watched a 15–30 min DVD each week about the challenges and successes experienced by patients with diabetes and afterwards discussed the video’s content with a peer coach in a 30–60 min telephone call. After 6 weeks, peer coaches made biweekly or monthly telephone calls over the remaining 4.5 months to monitor participants’ progress, review information, provide education, and develop self-management strategies. Control participants received a self-paced general health program on topics that were independent of study outcomes.

After 6 months, the study’s primary outcome, medication adherence, significantly improved in the intervention group vs. controls (-0.25; p < 0.0001), however the study arms did not differ in mean HbA1c, blood pressure, body weight, or LDL cholesterol. Intervention participants’ beliefs in the necessity of medications, their medication use self-efficacy, and their diabetes self-efficacy significantly increased, although participants’ self-rated quality of life was not significantly improved. The authors speculated that improvements in medication adherence may not have been substantial enough to affect the physiological measures after 6 months. A limitation that potentially attenuated outcomes was that follow-up blood draws for some participants were delayed for a significant period of time after completion of the intervention.

SMAs Utilizing Telehealth and Virtual Environments

Telehealth became heavily-utilized during the COVID-19 pandemic and has proven comparable to IP consultations in clinical effectiveness [41]. In Boston, MA (USA) a two-arm trial was implemented to compare conventional IP diabetes SMAs to virtual reality-augmented diabetes SMAs conducted via telehealth for African American or Black and Hispanic or Latina adult women with uncontrolled HbA1c (≥ 8.0%) [42].

A 3D computer-based simulated environment was used to engage study participants in SMAs and DSME using a telehealth platform with “immersive, experiential learning with animated educational content” [42]. Virtual world (VW) participants used personal avatars to represent themselves and engage with peers to carry out behavioral changes. They used the avatars to engage in SMAs and to practice the use of positive health behaviors such as dance and social support. Those in the VW group were provided with laptops and wireless internet access.

Both IP and virtual SMAs lasted 120 min including taking vital signs, documenting acute and chronic illness symptoms, health system visits, and self-management activities. All participants received the same 8-module DSME curriculum on topics including diabetes self-monitoring, preventive care, healthy eating, exercise, and stress management.

English- and Spanish-language cohorts of 6–12 individuals met in IP or VW settings for 8 weekly diabetes SMAs of 2-h duration. A healthcare provider met individually with each participant in a separate physical space or via a private telehealth session or telephone call for a one-on-one consult during every SMA. After 8 weeks, participants entered a 16-week maintenance phase when no formal SMAs occurred.

An intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis showed significant mean improvements in HbA1c from baseline to 6 months in the IP group (-0.8%; 10.2% to 9.4%) and in the VW group (-0.5%; 9.7% to 9.2%); between group differences were not statistically significant suggesting that the VW-based SMAs were no less effective than the traditional IP SMAs. Changes in HbA1c in a subset of participants completing at least 6 SMAs per protocol (PP) were similar to the results of the ITT analysis in that between group means were not significantly different.

Significant improvements in levels of physical activity were not observed in either the ITT or PP analyses. The investigators reported that participants had difficulties using the equipment to measure physical activity. Changes in depression scores within the IP and VM groups were non-significant, although substantial within group improvements were observed for diabetes distress in both groups.

Mechanisms of Peer Support

Peer support can play an important role in improving patients’ glycemic outcomes in T2DM [43]. Conceptually, peer support can be grounded in social cognitive theory [44] and self-determination theory [45]. Social cognitive theory proposes that learning can occur by observing the behavior of others and its consequences. Without the necessity of direct personal experience for learning, the volume of knowledge and skills that can be quickly learned by patients with T2DM is greatly expanded compared to experiential learning. Further, by observing peers as “social models,” self-efficacy and mastery of diabetes self-care behaviors may increase [44].

Self-determination theory posits that individuals are influenced by three factors: their capacity to exert control over their life and their future, their sense of competence (which increases with positive peer feedback which in turn increases motivation), and their connectedness to others [46]. Peer support can reinforce all 3 of these factors, particularly by providing positive feedback on behaviors, increasing self-efficacy, and leading to satisfying interpersonal connections [45].

The mechanisms of peer support relationships include having a shared lived experience, the identification of individual strengths, the provision of social and practical support, and the unique position of the peer as fellow patient, peer support specialist, or CHW cultural peer rather than a medical provider [47]. The mutual sharing of personal difficulties and experiences of suffering have been shown to increase feelings of normalization, connectedness and shared humanity [48, 49]. Because peers have faced many of the same problems, peer support is a practical way to learn ways to overcome barriers to diabetes self-management [6].

Discussion

Diabetes peer support interventions were associated with significant decreases in HbA1c in 6 of the 9 reviewed studies, and these findings align with those of older reviews. A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 studies showed that diabetes self-management education with integrated peer support reduced HbA1c levels, (SMD, -0.41; 95% confidence interval [50], -0.69 to -0.13; p < 0.001) [17•]. A scoping review by Lu et. al. found that a wide range of peer support models used as complements to primary care were associated with favorable improvements in HbA1c [51]. Further, a meta-analysis by Liang and colleagues found that peer support significantly improved self-efficacy compared with controls receiving usual care or usual diabetes education [SMD = 0.41, 95% CI = (0.20, 0.62), p = 0.0001], and self-management behaviors were significantly improved versus controls [SMD = 1.21, 95% CI = (0.58, 1.84), p = 0.0002] [18].

A sizeable decrease in HbA1c (-2.7%) was observed in a Nepal-based intervention study in which trained FCHVs held IP visits with the households of participants to provide diabetes education once every 4 months [37]. Although intervention contacts were infrequent and the FCHV interventionists were volunteers, it should be noted that FCHVs served as extenders of healthcare providers with whom they work closely at local clinics. As cultural peers to study participants, they were often regarded as integral, trusted member of their communities with whom a relationship had been established, often over many years. In addition, this was the only reviewed study that featured a household-based intervention, involving families in participants’ adoption of diet and lifestyle behaviors, attendance at clinic appointments, and modifications to medication adherence practices.

Mobile phones are nearly ubiquitous and can increase the number of contacts among peers. Six of the nine reviewed studies used mobile phones to support the intervention and four of these studies resulted in significant improvements in glycemic control. Several studies used both telephone calls and text messaging between peers and participants, providing more frequent opportunities for diabetes education, goal setting, problem-solving, trust-building, and strengthening of connections.

Healthcare system-sponsored diabetes education and peer support programs may have advantages compared to stand-alone peer support programs. Study participants were recruited at health clinics for 7 of the reviewed studies, 5 of which resulted in significant reductions in HbA1c. All three of the reviewed studies involving SMAs resulted in significant decreases in HbA1c, suggesting that directly integrating primary care providers and diabetes clinical services into diabetes education and peer support programs yields impactful benefits.

A study comparing VW SMAs to IP SMAs to found them to be comparable in effectiveness. The significant health risks posed by the COVID-19 pandemic to individuals with T2DM were reduced in the VW group as participants’ engaged in the intervention from their homes in comparison. In contrast, IP group visits were implemented in healthcare clinics in proximity to other patients and clinic staff. The VW intervention presents a potentially safer and more convenient way for T2DM patients to participate in SMAs and peer support programs while receiving benefits that are on par with IP SMAs.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this review. The review focuses on diabetes peer support interventions published over a relatively short 3-year time period. The review captured only studies published from 2021–2023 and does not include research published outside of this time frame.

Two of the included studies had modest sample sizes. Small samples have numerous disadvantages including increased risk of bias, increased variability, limited generalizability, and reduced statistical power, all of which can threaten the validity and reliability of a study’s findings.

The follow-up periods were only 6 months in duration for 2 of the 9 studies, which does not permit an evaluation of the longer-term durability of the treatment effect in diabetes, a long-term chronic disease. Due to the short time frames involved, caution should be exercised in drawing conclusions from these studies.

This review was intended to include a number of peer support interventions conducted during the period of the COVID-19 pandemic, which is recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO) to have started in March 2020 and ended in May 2023 [52]. However, it was difficult to determine the temporal overlap of the study periods with the pandemic. Although most of the included articles specified a date for the initiation of recruitment, they did not indicate an end date for the peer support intervention, which would have allowed it to be determined if the intervention extended into the pandemic period.

The pandemic was an event unrelated to study interventions but that may have influenced outcomes, and is a type of history bias. Interestingly, none of the articles discussed the possible influence of the pandemic on study participants’ experiences and study outcomes. Because there was no assessment of the effects of the pandemic on participants’ experiences in the reviewed studies, it is not possible to estimate its influence on outcomes. Additional research is needed to more closely examine the influence of the pandemic and other types of widespread disruptive events on patients with T2DM and the effects on peer support and outcomes.

It is important to note that diabetes peer support interventions are rarely studied in isolation. In the studies in the present review, peer support was part of a multifaceted intervention involving diabetes self-management education and sometimes clinical care. This makes it difficult to separate and isolate the effects of peer support from other aspects of the interventions. More research is needed to study the effects of peer support both alone and as part of multidimensional diabetes interventions.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that diabetes education and peer support interventions can be effective for improving control of HbA1c and blood pressure, however, they were not associated with significant improvements in body weight. Studies of peer support groups embedded within SMAs resulted in significant reductions in HbA1c, suggesting that the engagement of clinicians in diabetes peer interventions enhances outcomes. In the design of peer support programs, it may be advantageous to engage households, healthcare providers, and clinics in program implementation.

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

World health organization (WHO). Diabetes fact sheet. 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes. Accessed 17 May 2024.

International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 10th Edition. 2021.

Aceves B, Denman CA, Ingram M, Torres JF, Nuño T, Garcia DO, et al. Testing Scalability of a Diabetes Self-Management Intervention in Northern Mexico: An Ecological Approach. Front Public Health. 2021;9:617468. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.617468.

•• American Diabetes A. 5. Lifestyle Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(Suppl 1):S46-S60. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc19-S005. Provides current clinical practice recommendations for lifestyle management of diabetes that provides the general treatment goals and guidelines, components of diabetes care, and tools to evaluate quality of care.

Heisler M. Different models to mobilize peer support to improve diabetes self-management and clinical outcomes: evidence, logistics, evaluation considerations and needs for future research. Fam Pract. 2010;27 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):i23–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmp003.

Simmons D, Cohn S, Bunn C, Birch K, Donald S, Paddison C, et al. Testing a peer support intervention for people with type 2 diabetes: a pilot for a randomised controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-5.

ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, Bannuru RR, Brown FM, Bruemmer D, et al. 3. Prevention or Delay of Type 2 Diabetes and Associated Comorbidities: Standards of Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(Suppl 1):S41-S8. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc23-S003.

Shi C, Zhu H, Liu J, Zhou J, Tang W. Barriers to self-management of Type 2 diabetes during COVID-19 medical isolation: a qualitative study. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes: Targets Ther. 2020;13:3713–25. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S268481.

•• American Diabetes Association Professional Practice. A.5. Facilitating Behavior Change and Well-being to Improve Health Outcomes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(Suppl 1):S53-S72. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc21-S005. Discusses key recommendations for improving outcomes in T2DM through behavior change and evaluates the evidence supporting each recommendation.

Powers MA, Bardsley JK, Cypress M, Funnell MM, Harms D, Hess-Fischl A, et al. Diabetes self-management education and support in adults with type 2 diabetes: a consensus report of the american diabetes association, the association of diabetes care & education specialists, the academy of nutrition and dietetics, the american academy of family physicians, the American academy of PAs, the American association of nurse practitioners, and the American pharmacists association. Diabetes Educ. 2020;46(4):350–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721720930959.

Rose KJ, Scibilia R. The COVID19 pandemic - perspectives from people living with diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;173:108343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108343.

Singh AK, Khunti K. COVID-19 and diabetes. Annu Rev Med. 2022;73:129–47. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-042220-011857.

Dennis CL. Peer support within a health care context: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2003;40(3):321–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7489(02)00092-5.

Heisler M, Halasyamani L, Resnicow K, Neaton M, Shanahan J, Brown S, et al. “I am not alone”: the feasibility and acceptability of interactive voice response-facilitated telephone peer support among older adults with heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2007;13(3):149–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-5299.2007.06412.x.

Skinner TC, Joensen L, Parkin T. Twenty-five years of diabetes distress research. Diabet Med. 2020;37(3):393–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.14157.

Daniels AS, Bergeson S, Myrick KJ. Defining Peer Roles and Status Among Community Health Workers and Peer Support Specialists in Integrated Systems of Care. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(12):1296–8. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201600378.

• Azmiardi A, Murti B, Febrinasari RP, Tamtomo DG. The effect of peer support in diabetes self-management education on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology and health. 2021;43:e2021090. https://doi.org/10.4178/epih.e2021090. A review of the effectiveness of diabetes self-management education interventions with integrated peer support on glycemic control in patients with T2DM.

Liang D, Jia R, Zhou X, Lu G, Wu Z, Yu J, et al. The effectiveness of peer support on self-efficacy and self-management in people with type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(4):760–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2020.11.011.

Izzo R, Pacella D, Trimarco V, Manzi MV, Lombardi A, Piccinocchi R, et al. Incidence of type 2 diabetes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Naples, Italy: a longitudinal cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;66:102345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102345.

Sujan MSH, Tasnim R, Islam MS, Ferdous MZ, Apu MAR, Musfique MM, et al. COVID-19-specific diabetes worries amongst diabetic patients: The role of social support and other co-variates. Prim Care Diabetes. 2021;15(5):778–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcd.2021.06.009.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906.

Dale JR, Williams SM, Bowyer V. What is the effect of peer support on diabetes outcomes in adults? Syst Rev Diabet Med. 2012;29(11):1361–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03749.x.

Kirsh SR, Aron DC, Johnson KD, Santurri LE, Stevenson LD, Jones KR, et al. A realist review of shared medical appointments: How, for whom, and under what circumstances do they work? BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):113. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2064-z.

• Heisler M, Burgess J, Cass J, Chardos JF, Guirguis AB, Strohecker LA, et al. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Diabetes Shared Medical Appointments (SMAs) as Implemented in Five Veterans Affairs Health Systems: a Multi-site Cluster Randomized Pragmatic Trial. Journal of general internal medicine. 2021;36(6):1648–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06570-y. Multi-site RCT that examined the effects of implementing SMAs on glycemic control and other metabolic outcomes in more than 1500 patients with T2DM.

Lopez Sanchez GF, Lopez-Bueno R, Villasenor-Mora C, Pardhan S. Comparison of diabetes mellitus risk factors in Mexico in 2003 and 2014. Front Nutr. 2022;9:894904. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.894904.

Rosales CB, Denman CA, Bell ML, Cornejo E, Ingram M, Del Carmen Castro Vasquez M, et al. Meta Salud Diabetes for cardiovascular disease prevention in Mexico: a cluster-randomized behavioural clinical trial. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50(4):1272–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyab072.

Sampson M, Clark A, Bachmann M, Garner N, Irvine L, Howe A, et al. Effects of the Norfolk diabetes prevention lifestyle intervention (NDPS) on glycaemic control in screen-detected type 2 diabetes: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):183. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-021-02053-x.

Vongmany J, Luckett T, Lam L, Phillips JL. Family behaviours that have an impact on the self-management activities of adults living with Type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. Diabet Med. 2018;35(2):184–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13547.

Bennich BB, Roder ME, Overgaard D, Egerod I, Munch L, Knop FK, et al. Supportive and non-supportive interactions in families with a type 2 diabetes patient: an integrative review. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2017;9:57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-017-0256-7.

Nelson LA, Spieker AJ, Greevy RA Jr, Roddy MK, LeStourgeon LM, Bergner EM, et al. Glycemic outcomes of a family-focused intervention for adults with type 2 diabetes: Main, mediated, and subgroup effects from the FAMS 2.0 RCT. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2023;206:110991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2023.110991.

Rosland AM, Piette JD, Trivedi R, Lee A, Stoll S, Youk AO, et al. Effectiveness of a Health Coaching Intervention for Patient-Family Dyads to Improve Outcomes Among Adults With Diabetes: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2237960. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.37960.

Tang TS, Afshar R, Elliott T, Kong J, Gill S. From clinic to community: a randomized controlled trial of a peer support model for adults with type 2 diabetes from specialty care settings in British Columbia. Diabet Med. 2022;39(11):e14931. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.14931.

Tang TS, Sidhu R, Halani K, Elliott T, Sohal P, Garg A. Participant-directed intervention tailoring is associated with improvements in glycemic control for South Asian adults with type 2 diabetes. Can J Diabetes. 2022;46(3):287–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjd.2021.11.003.

Jeet G, Thakur JS, Prinja S, Singh M. Community health workers for non-communicable diseases prevention and control in developing countries: Evidence and implications. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0180640. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180640.

Hunt CW, Grant JS, Appel SJ. An integrative review of community health advisors in type 2 diabetes. J Community Health. 2011;36(5):883–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-011-9381-7.

Gyawali B, Neupane D, Vaidya A, Sandbaek A, Kallestrup P. Community-based intervention for management of diabetes in Nepal (COBIN-D trial): study protocol for a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19(1):579. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-018-2954-3.

Gyawali B, Sharma R, Mishra SR, Neupane D, Vaidya A, Sandbæk A, et al. Effectiveness of a female community health volunteer-delivered intervention in reducing blood glucose among adults with type 2 diabetes: an open-label, cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2035799. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35799.

Vaughan EM, Hyman DJ, Naik AD, Samson SL, Razjouyan J, Foreyt JP. A Telehealth-supported, Integrated care with CHWs, and MEdication-access (TIME) Program for Diabetes Improves HbA1c: a Randomized Clinical Trial. J Gen int med. 2021;36(2):455–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06017-4.

Andreae SJ, Andreae LJ, Cherrington AL, Richman JS, Johnson E, Clark D, et al. Peer coach delivered storytelling program improved diabetes medication adherence: a cluster randomized trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2021;104:106358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2021.106358.

Andreae SJ, Andreae LJ, Cherrington A, Richman J, Safford M. Peer coach delivered storytelling program for diabetes medication adherence: Intervention development and process outcomes. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2020;20:100653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conctc.2020.100653.

Carrillo de Albornoz S, Sia KL, Harris A. The effectiveness of teleconsultations in primary care: systematic review. Fam Pract. 2022;39(1):168–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmab077.

Mitchell SE, Bragg A, De La Cruz BA, Winter MR, Reichert MJ, Laird LD, et al. Effectiveness of an immersive telemedicine platform for delivering diabetes medical group visits for African American, black and hispanic, or latina women with uncontrolled diabetes: the women in control 20 noninferiority randomized clinical trial. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e43669. https://doi.org/10.2196/43669.

Peimani M, Monjazebi F, Ghodssi-Ghassemabadi R, Nasli-Esfahani E. A peer support intervention in improving glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(3):460–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.10.007.

Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behavior. 2004;31(2):143–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104263660.

Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68.

Ryan RM, Patrick H, Deci EL, Williams GC. Facilitating health behaviour change and its maintenance: Interventions based on Self-Determination Theory. Eur Health Psychol. 2008;10(March):2–5.

Watson E. The mechanisms underpinning peer support: a literature review. J Ment Health. 2019;28(6):677–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1417559.

Kotera Y, Llewellyn‑Beardsley J, Charles A, Slade M. Common Humanity as an Under‑acknowledged Mechanism for Mental Health Peer Support. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. First published online September 19, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00916-9.

Alasiri E, Bast D, Kolts RL. Using the implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) to explore common humanity as a dimension of self-compassion. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2019;14:65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.09.004.

Horigan G, Davies M, Findlay-White F, Chaney D, Coates V. Reasons why patients referred to diabetes education programmes choose not to attend: a systematic review. Diabet Med. 2017;34(1):14–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.13120.

Lu S, Leduc N, Moullec G. Type 2 diabetes peer support interventions as a complement to primary care settings in high-income nations: a scoping review. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(11):3267–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2022.08.010.

World Health Organization (WHO). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: Overview 2024 [4/14/24]. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/covid-19. Accessed 17 May 2024.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JJW wrote the main manuscript. KU and PY provided editing and feedback and reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Werner, J.J., Ufholz, K. & Yamajala, P. Recent Findings on the Effectiveness of Peer Support for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 18, 65–79 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12170-024-00737-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12170-024-00737-6