Abstract

Maladaptive Daydreaming (MD) is a dysfunctional mental activity characterized by an excessive immersion in fantasy, whose function is being increasingly discussed and investigated. Accordingly, this study aims to examine its function as an emotion regulation strategy among MDers by evaluating the pattern of associations among MD, emotion regulation (ER) difficulties, anxiety, depression, stress symptoms, and negative problem-solving orientation. The mediating role of MD level in the association between difficulties in ER and both the psychological distress variables and negative problem-solving orientation was evaluated. N = 252 MDers, aged 18–70 years (Mage = 30.63, SD = 11.40, 84.1% females), participated in the study and completed self-report measures. Some unexpected results emerged: among difficulties in ER’s dimensions, only lack of emotional self-awareness negatively and significantly associated with all symptom variables; solely difficulty pursuing goals when experiencing negative emotions and reduced trust in one’s capacity to self-regulate positively and significantly correlated with MD. MD negatively correlated with depression, anxiety, and negative problem-solving orientation. Three mediation models showed the mediating role of MD in reducing the negative effect of difficulty pursuing goals when experiencing negative emotions on both anxiety and negative problem-solving orientation and of trust in one’s capacity to self-regulate on negative problem-solving orientation. Overall, findings seem to point to functional peculiarities among MDers and support the view of MD as an emotion regulation strategy allowing the management and reduction of negative emotions and negative perceptions of problem situations. Notwithstanding, further research evaluating the potential moderating role of MD-specific fantasies is warranted. Unexpected findings are discussed.

Highlights

-

1)

The role of MD level in the association between anxiety, depression, stress, and negative problem-solving orientation, and ER difficulties.

-

2)

Among ER dimensions, only Difficulty pursuing Goals and No Trust in Strategy selection show a relevant positive association with MD.

-

3)

MD negatively correlates with depression, anxiety, and negative problem-solving orientation.

-

4)

MD reduces the impact of Difficulty pursuing Goals when feeling negative emotions on anxiety symptoms and negative problem-solving orientation.

-

5)

MD reduces the impact of No trust in Strategy selection on negative problem-solving orientation.

-

6)

MD seems to function as an ER strategy; however, its effect might be only short-term.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Maladaptive daydreaming

Literature suggests that individuals use daydreaming as a coping strategy for stress (Winnicott, 1971). For example, Singer (1975) viewed daydreaming as a typical cognitive activity used to develop daily planning skills, manage emotions better, and integrate different life experiences. Several studies have been conducted on the cognitive activity of daydreaming, including the possibility that it could become pathological (Mooneyham & Schooler, 2013; Singer, 1975). This pathological form of daydreaming, better known as Maladaptive Daydreaming (MD) was first coined by Somer (2002). He defined MD as an “extensive fantasy activity that replaces human interactions and/or interferes with the individual’s academic, interpersonal or vocational functioning” (Somer, 2002, p. 199). The characteristics of MD that differentiate it from typical daydreaming are (a) constant craving for fantasies, (b) high levels of experienced presence, (c) stereotypical and repetitive movements (e.g., swinging, walking), and (d) to get absorbed into and sustain one’s fantasy (Schimmenti et al., 2020; Soffer-Dudek et al., 2020; Somer et al., 2016a).

Various hypotheses have been proposed regarding the origin of this phenomenon. Initially, Somer (2002) believed it could stem from traumatic events, suggesting that instead of creating an imaginary friend, the person generates an alternative, safer, and controllable world. Shortly thereafter, Somer et al. (2016a) found that while traumatic experiences may contribute to MD, not all subjects have experienced a direct traumatic event. This led to the hypothesis that MD results from a more complex framework and not just a single cause (Somer et al., 2016a). Several scientific studies have reported the presence of an absorptive component that appears to be closely associated with MD (Somer & Herscu, 2017). At the same time, many studies suggest that MD comprises a dissociative component (Pietkiewicz et al., 2018; Ross et al., 2020; Soffer-Dudek & Somer, 2023; Somer, 2002), particularly in terms of the ability to “absorb” into another reality and the presence of different “alter-egos” represented by other versions of themselves and by characters within complicated stories. In line with this, a recent proposal called for viewing MD as an “absorption disorder” (Soffer-Dudek & Somer, 2023). The authors suggested that MD should be seen as existing on a continuum. At one extreme are normal or less severe forms of dissociation-like states, such as externalizing thoughts and creative writing. At the other extreme are severe dissociative conditions, including dissociative identity disorder (DID). Thus, MD would be considered a less severe dissociative disorder, positioned just before the DID category on this continuum (Soffer-Dudek & Somer, 2023). Other authors, such as Bigelsen et al., (2016), have stressed that Maladaptive Daydreamers (MDers) feel an increasing urge to fantasize upon awakening and immediately after being interrupted, highlighting salient features such as mood modification, tolerance, relapse, and withdrawal. These features led researchers to conceptualize and investigate MD as a potential behavioral addiction (Bigelsen et al., 2016; Griffiths, 2005; Pietkiewicz et al., 2018). Although these different conceptualizations exist, it is necessary to acknowledge that MD is not yet recognized within diagnostic manuals.

Notwithstanding, growing evidence points to the potential for including MD as a psychological disorder (Soffer-Dudek & Theodor-Katz, 2022). Multiple research studies have reported associations between MD and symptoms such as depression and anxiety (Chirico et al., 2022; Musetti et al., 2021; Soffer-Dudek & Somer, 2018), with high comorbidity rates for these disorders at 66.7% and 71.8% respectively (Salomon-Small et al., 2021; Somer et al., 2017a, b). The literature has indeed underlined the complexity of the psychopathological landscape of MD, recognizing the impairment and distress experienced by individuals engaging in MD (Somer et al., 2017a, b). To deepen understanding of MD, scholars have delved into the investigation of the function that MD might play, pointing at an escapist function that allows one to avoid and/or evade distressing states (Somer, 2002). Accordingly, it was not long before researchers attempted to study the relationship between MD and emotional regulation (ER), a transdiagnostic process that underlies the development and maintenance of multiple clinical conditions (Cludius et al., 2020; Sloan et al., 2017).

Maladaptive daydreaming and emotional regulation

Multiple studies have found intriguing connections and associations between MD and ER (Pyszkowska et al., 2023; Sándor et al., 2023; West & Somer, 2020). ER is the process by which individuals process and manage their emotional states and associated behavioral responses; maladaptive responses to distressing feelings are regarded as emotion dysregulation (Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Gross, 2013). From a multidimensional perspective, this intricate process encompasses an individual’s self-awareness and ability to recognize and accept emotions. It also involves the capacity for impulse and behavioral control when experiencing negative emotions, along with one’s overall sense of efficacy in managing emotions and selecting appropriate ER strategies (Gratz & Roemer, 2004). In this context, past studies have reported an association between MD and all of the above-mentioned ER dimensions (Pyszkowska et al., 2023; Sándor et al., 2023; Thomson & Jaque, 2023; West & Somer, 2020), showing that greater difficulties in all dimensions were associated with increased MD. Indeed, research indicates that people with MD have greater difficulty in managing negative emotions, which includes an inability to mobilize emotional management strategies, greater difficulty in accepting negative feelings, difficulty in controlling impulse-driven behavior, and greater difficulty in engaging in goal-directed behavior (Pyszkowska et al., 2023; Thomson & Jaque, 2023). West and Somer (2020) further found that both immersive daydreaming and MD were associated with difficulties in ER, leading them to conclude that any form of exaggerated daydreaming may provide temporary relief from negative emotions. As such, it has been hypothesized that daydreaming may serve as a form of ER strategy, with the effectiveness varying based on the level of distress experienced (Somer et al., 2019).

In this respect, the literature suggests that MD might serve as a means to avoid unpleasant memories and/or emotions, offering respite and soothing effects (Somer, 2002), by using immersion in fantasy to seek emotional support from imaginary characters and/or to avoid negative emotions (Somer et al., 2016a, b). However, a recent longitudinal study (Soffer-Dudek & Somer, 2018) investigating the relationship between MD and emotional experience observed that negative emotions and depression symptoms followed, yet did not proceed, to more intense and prolonged MD, and were associated with reduced positive emotions. This led the authors to hypothesize that the pleasure associated with MD might be short-term, thus providing only a brief momentary relief; as such, it does not favor lasting positive emotions and may lead to increased negative ones. The negative emotionality linked to increased and more intense MD (Soffer-Dudek & Somer, 2018) aligns with evidence reporting that what MDers perceive as most distressing is the difficulty in stopping or impeding MD (Greene et al., 2020; Schimmenti et al., 2020), thus stressing the maladaptive nature of MD (Soffer-Dudek & Somer, 2018).

The present study: aim and hypotheses

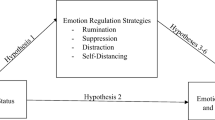

Given the conflicting evidence and discourses reported in the literature, the goal of this study is to further the investigation of MD’s function as an ER strategy (Somer et al., 2019). More specifically, previous research (Somer, 2002; Somer et al., 2016a, b; Thomson & Jaque, 2023) has conceptualized daydreaming as a strategy adopted by individuals to cope with difficult experiences and/or overwhelming emotions. Its use as a form of escape from negative emotions and/or to search for positive emotions, even if generated by immersion in fantasy, may be one of the reasons why individuals who can fantasize in an immersive manner begin to overuse it, to the point of becoming maladaptive. However, although some reported positive feelings following MD (Somer, 2002), thus justifying increased reliance on it, others reported the opposite (Soffer-Dudek & Somer, 2018), thereby stressing the maladaptive nature of MD. Notwithstanding, although on the rise, literature specifically dedicated to investigating MD as an ER strategy remains limited. As such, adding to the available literature, the present study examines the pattern of associations between MD level, difficulties in ER, and symptoms of anxiety, depression, and stress within a sample of individuals experiencing MD. Furthermore, in line with existing evidence that portrays MD as a mode to evade reality and deal with challenging situations (Somer, 2002; Somer, et al., 2016a), its association with negative problem-solving orientation will also be evaluated. To present knowledge, no previous study has included this construct when investigating MD. It encompasses cognitive components relevant to interpreting problematic events as threatening, perceiving low self-efficacy, believing in inadequate problem-solving abilities, and maintaining pessimism about the outcomes of problem-solving (Bottesi & Ghisi, 2017). Therefore, evaluating how MD might influence such negative problem-solving orientation in MDers is expected to provide insights into how their immersion in fantasy might alter their perception of problematic situations and thus its use as a regulation strategy. We expect to find significant positive associations between MD and difficulties in ER (Pyszkowska et al., 2023; Sándor et al., 2023; Thomson & Jaque, 2023; West & Somer, 2020), while the association between MD and negative problem-solving-orientation will be exploratively evaluated. Ultimately, to evaluate further the process whereby MD might function as an ER strategy, mediation models will be performed. More specifically, this study hypothesizes a positive association between difficulties in ER and both the psychological symptoms considered (Everaert & Joormann, 2019; Schäfer et al., 2017) and negative problem-solving orientation (Belavkin, 2001; Malmivuori, 2006), and investigates the mediating role of MD in these associations.

Method

Participants and procedure

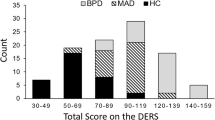

Data were collected through an elaborate Google Form questionnaire that was prepared and shared via various social media platforms (e.g., Facebook) in MD-related channels. Anonymity for all participants was guaranteed and informed consent, included within the survey link, was collected before the administration of the surveys. Participation was voluntary and participants were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any moment without incurring any repercussions and ensuring the non-use of their data. Thus, the data was collected through snowball sampling and our initial sample size was N = 312 participants; 60 participants were then excluded since they did not reach the cut-off level needed to be classified as MDers (Maladaptive Daydreaming Scale-16, MDS-16 ≥ 51; Schimmenti et al., 2020). The final sample size thus included N = 252 participants aged between 18 and 70 years (M = 30.63; SD = 11.40) with females forming a majority of the sample at 84.1%.

Measurement instrument

Maladaptive Daydreaming Scale-16

The MDS-16 (Italian validation; Schimmenti et al., 2020) is a self-report questionnaire consisting of 16 items scored on a scale ranging from 0 to 100% with 10% intervals (0% = Never to 100% = All the time). The two subscales that this questionnaire measures are the level of somatosensory retreat and the level of interference with life. Combining the scores on the two subscales allows us to arrive at a total score indicating the severity of MD. A total score ≥ 51 suggests the presence of probable MD (Schimmenti et al., 2020). In the present study the total score showed a highly satisfactory internal consistency: α = 0.90. An example item is “When you get up in the morning, how strong is your urge to start daydreaming immediately?” (Item 13).

Difficulties in emotion regulation- short form

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation- Short Form (DERS-SF; Italian validation; Rossi et al., 2023) is an 18-item short-form scale derived from the DERS which is a scale commonly used to assess difficulties in ER (Gratz & Roemer, 2004). This scale contains 6 domains; (a) lack of emotional awareness, (b) lack of emotional clarity, (c) difficulties engaging in goal-directed behavior, (d) lack of trust in one’s capacities to select adaptive ER strategies, (e) impulse control difficulties and (f) non-acceptance of emotional responses. This scale is measured on a 5-point Likert Scale (1 = almost never, 5 = almost always), with higher scores indicating a heightened difficulty in regulating one’s emotions. In the present study, the six sub-scales were considered, all showing a satisfactory internal consistency: Non-acceptance of Emotions α = 0.64; Difficulty pursuing Goals α = 0.81; No trust in Strategy selection α = 0.50; Difficulty in Impulse control α = 0.73; Lack of Clarity α = 0.60; Lack of Awareness α = 0.61. An example of an item is “When I am upset, I am embarrassed to feel this way” (Item 12).

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale

The Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS; Italian validation Bottesi et al., 2015) is a 21-item self-report instrument that measures levels of anxiety, stress, and depression. Each item is measured on a 4-point Likert Scale (0 = Never happened, 3 = Happens almost always); participants are asked to answer each item considering the previous seven days. The instrument provides three different measures for anxiety, depression, stress symptoms level, and an overall distress score. In the present study, the three sub-scales were considered, all showing a satisfactory internal consistency: Depression symptoms α = 0.70; Anxiety symptoms α = 0.73; Stress symptoms α = 0.67. An example item is “I have felt that life is meaningless” (Item 21).

Negative problem orientation questionnaire-revised

The Negative Problem Orientation Questionnaire-Revised (NPOQ-R; Italian validation Bottesi & Ghisi, 2017) is a self-report measure designed to evaluate the cognitive component of negative problem orientation. More specifically, it evaluates the attitude toward problem-solving as regards the interpretation of problematic events as threatening, the perception of low self-efficacy, and the belief of possessing inadequate problem-solving abilities, combined with pessimism about the outcomes of problem-solving that ultimately contribute to a state of low frustration tolerance. The instrument consists of 12 items measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Completely disagree to 5 = Completely agree) where a high total score indicates a negative orientation to problem-solving. This instrument showed satisfactory internal consistency (α = 0.77); an example item is “I often see problems as bigger than they are” (Item 10).

Data analysis

Analyses were performed using RStudio and SPSS. After assessing demographic information and descriptive statistics (categorical variables: N, %; continuous variables: M, SD), bi-variate Pearson’s r correlations were computed (p < 0.05) and interpreted when r ≥ 0.20 (r ≥ 0.30 medium effect; r ≥ 0.50 = large effect; Cohen, 1988). Based on the correlational results obtained simple mediational models were calculated through SPSS PROCESS Macro (Model 4, Fig. 1; Hayes, 2022) including MD level as mediator; the sample’s age was included as a covariate. Slopes (i.e., β) were not standardized. For hypothesis testing, the bootstrapping method – a high-power non-parametric test – was employed by applying 5000 bootstraps. The obtained bootstrap 95% confidence interval is considered significant when it does not include 0, thereby indicating significant associations.

Mediation Models (PROCESS Model 4): The mediating role of MD in the association between Difficulties pursuing Goals on Anxiety symptoms (a) and Negative Problem-Solving orientation (b) and in the association between No trust in Strategy selection and Negative Problem-Solving orientation (c). Note. Slopes are not standardized; * p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001

Results

Demographic information is reported in Table 1 and descriptive statistics in Table 2.

Correlations

Pearson’s r bi-variate correlations are shown in Table 3. Results highlighted that MD only showed a significant and positive medium effect size correlation with the Difficulty pursuing Goals dimension of difficulties in ER. A further significant positive correlation emerged with the No trust in Strategy selection dimension, yet with a slightly smaller effect size. MD then significantly and negatively correlated with Depression and Anxiety symptoms as well as Negative Problem-Solving orientation. Negative Problem-Solving orientation also negatively and significantly correlated with the Difficulty pursuing Goals and No trust in Strategy selection dimensions. Among the difficulties in ER dimensions, only Lack of Awareness is negatively and significantly associated with all three symptom variables (i.e., Depression, Anxiety as well as Stress symptoms). Nonetheless, Difficulty pursuing Goals is also negatively and significantly associated with Anxiety symptoms. Instead, Stress symptoms positively and significantly correlated with Difficulty in Impulse control. Among each other, the dimensions of difficulties in ER were minimally correlated, with only Difficulty pursuing Goals and No trust in Strategy showing a significant positive medium effect size correlation.

Mediational models

The mediational models calculated are shown in Fig. 1 and were performed in line with the correlational results presented above. As such, only three models were calculated. MD was included as the mediator in all three models; in models a) and b) the Difficulty pursuing Goals (when experiencing negative emotions) dimension was included as an independent variable, while in model c) it was the No trust in Strategy selection dimensions. Finally, in model a) the Anxiety symptoms variable was included as a criterion variable, while in both models b) and c) it was Negative Problem-Solving orientation.

In both models a) and b) the significant and positive association between the Difficulty pursuing Goals dimension and MD has emerged (For both models: β = 7.07; SE = 1.43; t = 4.94; 95% CI = 4.25, 9.90; R2 = 13.07%) as well as the significant direct negative effect of the former on Anxiety symptoms (β = -0.12; SE = 0.04; t = -3.14; 95% CI = -0.19, -0.04) and Negative Problem-Solving orientation (β = -1.12; SE = 0.45; t = -2.48; 95% CI = -2.02, -0.23). No trust in Strategy selection also positively and significantly associated with MD (β = 7.22; SE = 1.71; t = 4.22; 95% CI = 3.85, 10.59; R2 = 10.93%), and showed a direct significant negative effect on Negative Problem-Solving orientation (β = -2.05; SE = 0.52; t = -3.96; 95% CI = -3.07, -1.03).

MD negatively and significantly associated with Anxiety symptoms (β = -0.004; SE = 0.002; t = -2.56; 95% CI = -0.007, -0.0009) as well as Negative Problem-Solving orientation (Model b: β = -0.05; SE = 0.02; t = -2.40; 95% CI = -0.08, -0.008; Model c: β = -0.04; SE = 0.02; t = -2.22; 95% CI = -0.08, -0.01). Accordingly, all indirect effects were significant. More specifically, the indirect effect of Difficulty pursuing Goals on Anxiety symptoms as mediated by MD was observed (β = -0.03; SE = 0.01; 95% CI = -0.05, -0.006); the model’s R2 for Anxiety symptoms was 8.64%. In model b as well the indirect effect of Difficulty pursuing Goals on Negative Problem-Solving orientation as mediated by MD was observed (β = -0.33; SE = 0.16; 95% CI = -0.68, -0.06); Model b’s R2 for Negative Problem-Solving orientation was 8.57%. The sample’s Age, as a covariate, in models a) and b) was significant only for the association between Difficulty pursuing Goals and MD Interference with life (For both models: β = -0.44; SE = 0.15 t = -2.98; 95% CI = -0.73, -0.15).

Finally, also the indirect effect of No trust in Strategy selection on Negative Problem-Solving orientation as mediated by MD was observed (β = -0.30; SE = 0.14; 95% CI = -0.61, -0.04). In this model as well, the sample’s Age, as covariate, was significant only for the association between No trust in Strategy selection and MD (β = -0.47; SE = 0.15 t = -3.11; 95% CI = -0.76, -0.17); model c’s R2 for Negative Problem-Solving orientation was 11.81%.

Discussion

The present study aimed at deepening the understanding of MD as a form of ER strategy. We did so by exploring the association between MD level, difficulties in ER’s dimensions as well as depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms in an MDers sample. Furthermore, we explored the association between MD level and MDers’ attitude toward negative problem-solving orientation, which subsumes the cognitive components relevant to the interpretation of problematic events as threatening the perception of low self-efficacy, and the belief of possessing inadequate problem-solving abilities with pessimism about outcomes of problem-solving.

Overall, contrary to expectations from the broader literature, our data revealed minimal associations among the different ER dimensions (Gratz & Roemer, 2004; Moreira et al., 2022; Rossi et al., 2023), as well as between the latter and MD (Pyszkowska et al., 2023; Sándor et al., 2023; Thomson & Jaque, 2023; West & Somer, 2020) and the symptom variables considered (Everaert & Joormann, 2019; Schäfer et al., 2017). These results suggest that among MDers, these dimensions of ER might hold a different quality as compared to normative samples. On a similar note, in a previous study comparing MDers and Non-MDers (Chirico et al., 2022), it was noted that the ER strategy of reappraisal, which significantly contributed to the pattern of association with psychopathological symptoms among Non-MDers, played a marginal role among MDers. This led the authors (Chirico et al., 2022) to suggest the presence of significant functional differences between individuals with MD and those without it, implying that ER dimensions may acquire qualitatively different nuances among MDers. In this context, it is noteworthy that only heightened Difficulties in Impulse control during negative emotional experiences were associated with increased stress symptoms, which aligns with expectations. This seems consistent with evidence highlighting distress among MDers when feeling unable to stop the urge to daydream (Greene et al., 2020), which may contribute to elevated stress symptoms. Differently, the ER dimension regarding the Lack of Emotional Self-awareness exhibited a significant association with depression, anxiety, as well as stress symptoms. However, such association was negative, suggesting that greater emotional self-awareness, among individuals experiencing MD, is linked to increased psychological symptoms. Emotional self-awareness involves recognizing, distinguishing, and modulating emotional states, shaped by interactions with one’s environment (Levenson, 1994), thus necessitating continuous balanced monitoring of oneself and one’s surroundings. It is worth noting that previous research has highlighted MDers’ tendency to exhibit overexcitability (Thomson & Jaque, 2023) while simultaneously adopting self-suppression escapism strategies to deal with problematic situations (Pyszkowska et al., 2023). Indeed, MD has been proposed as an avoidance-based strategy, serving as an escapist approach to detach oneself from life experiences and emotions (Pyszkowska et al., 2023). Given that emotional self-awareness involves processing a multitude of internal and external stimuli, MDers might find it particularly challenging to suppress their emotions. Consequently, they may experience heightened awareness as overwhelming, leading to an increase in distress. Interestingly, contrary to past evidence (Somer et al., 2017a, b), our findings suggest that among MDers, increased MD is associated with reduced depression and anxiety symptoms, as well as a decrease in negative attitudes toward problem-solving. This supports the mentioned escapist function of MD, working as a buffer against negative emotional states related to depression and anxiety symptoms; furthermore, cognitively, it may provide a sense of enhanced efficacy and possibility to cope with life problems, aligning with evidence emphasizing MD’s function in allowing disengagement from stressful situations by favoring mood enhancement (Somer, 2002). Adding to the above, our results further highlighted that the reduced trust in one’s capacity to adaptively self-regulate and increased difficulties in deploying attention from negative emotions are associated with an increase in MD. This is in line with past propositions hypothesizing that a potential mechanism underlining the association between MD and difficulties in ER could be related to MDers’ difficulty in disengaging thoughts and redirecting their attention due to deficits in cognitive control (Chirico et al., 2022; Greene et al., 2020). Cognitive control is a neuro-cognitive construct that involves the capacity to select, based on the task at hand and the context, appropriate emotions, thoughts, and behaviors, while simultaneously suppressing habitual actions that are not suitable (Miller & Cohen, 2001). This description echoes the defining characteristics of MD, where individuals become increasingly absorbed in fantasy to the extent that they find it particularly difficult, or even impossible, to stop such mental activity, as well as the associated stereotypical and repetitive movements and behaviors enacted during fantasy immersion (Schimmenti et al., 2020; Soffer-Dudek et al., 2020; Somer, 2002; Somer et al., 2016a). As such, in line with the above-mentioned escapist function of MD (Somer, 2002), our data seem to suggest the presence of a vicious cycle, whereby as individuals experience increased difficulty disengaging from negative emotions, their cognitive control over their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors diminishes. However, subsequently, because MDers often experience distress associated with this loss of control (Greene et al., 2020), their confidence in their ability to self-regulate may diminish, making it harder for them to find alternative self-regulation strategies. In other words, they might experience difficulties in disengaging attention from both negative emotions and MD which could then further reduce their perceived efficacy as regards the selection and employment of more adaptive ER strategies.

Taken together, our results strengthen the above discourse, which is reflected in the results obtained from the mediational models performed. Against expectations (Everaert & Joormann, 2019; Schäfer et al., 2017), results showed that, among probable MDers, greater difficulties in deploying attention from negative emotions are associated with reduced anxiety symptoms. Furthermore, heightened difficulties in redirecting attention from negative emotions and diminished trust in one’s capacity to adaptively self-regulate were both associated with a reduced negative orientation towards problem resolution. Importantly, in all three models, the mediating effect of MD between these associations emerged, indicating the presence of the previously discussed process. In other words, as individuals experiencing MD perceive themselves as less proficient in self-regulation and face increased difficulty detaching themselves from negative emotions, the inclination to engage in fantasies intensifies (Greene et al., 2020); this ultimately enables them to alleviate their feelings of anxiety. Simultaneously, this inclination toward engaging in fantasies, as seen in individuals experiencing MD, could potentially lead to an improvement in their attitude toward the problems at hand (Somer, 2002). Alternatively, it may allow them to disengage from the demands of problem-solving altogether. Based on these results, evidence seems to suggest similarities between the function played by MD and the principles of exposure therapy, a well-documented strategy that aims to expose individuals to objects they fear within safe and controlled environments (Telch et al., 2014). One aspect of exposure therapy is imaginal exposure where individuals are made to vividly imagine the feared situations or objects (Arntz et al., 2007). It is plausible that MD could work as a type of imaginal exposure where individuals immerse themselves in anxiety-eliciting daydreams that over time have the potential to reduce anxiety and negative feelings at large by allowing a vivid – yet safer – context for emotional processing. Indeed, a previous study showed that a more positive MD was associated with greater emotional clarity (Greene et al., 2020). However, aligning with past evidence (Soffer-Dudek & Somer, 2018) pointing to the seemingly short-term benefit of MD, our findings should be interpreted with caution until replication. Notwithstanding, this is noteworthy considering the evidence discussing the addictive components of MD (Pietkiewicz et al., 2018; Somer, 2018), whereby the short-term positive feelings experienced through increased fantasy immersion might result from its usually rewarding nature (Somer et al., 2016b), which then might lead to an increasing crave for it (Bigelsen et al., 2016). Such an increasing need to fantasize aligns with the concept of tolerance, untimely fostering the frequency and intensity of the behavior to continue experiencing that short-lived sense of reward (Griffiths, 2005; Pietkiewicz et al., 2018; Somer et al., 2016a). Instead, another valuable perspective we could refer to is that of the expectation fulfillment theory (Griffin & Tyrrell, 2014). This theory posits that the main function of dreams is to engage with emotional arousals that were not acted out in the previous day. Accordingly, in line with previous propositions from the literature (Greene et al., 2020; Somer, 2002), this seems to support the view that as a response to increased ER-related difficulties, MDers use MD as a form of need fulfillment. However, it is reasonable to anticipate that different themes of fantasies among MDers might moderate the understanding of the function of MD, reflecting varying needs among this population (Somer, 2002).

Notwithstanding, is noteworthy that the direct negative effects of the two dimensions of ER on anxiety and negative problem-solving orientation were significant even when accounting for MD. This aspect remains an open question that warrants future investigation; however, a potential moderator of such an association could be related to the perceived enjoyability of MD. Specifically, beyond deficits in cognitive control contributing to increased and intensified MD, if fantasies are perceived as enjoyable and need-fulfilling (Greene et al., 2020; Somer, 2002), difficulties in ER might serve as a maladaptive driving force, furthering the inclination to immerse oneself in the safe space of fantasy. Fantasy immersion could thus allow for a freer and consequence-free emotional expression, ultimately leading to a more positive emotional state. While these ideas are speculative, this evidence underscores important functional peculiarities among individuals experiencing MD.

Limitations and considerations for future research

Some limitations should be considered for a comprehensive interpretation of our study results. Firstly, although the overall sample size was satisfactory, it should be noted that most of our sample consisted of females and a significant portion were students, which represents a limitation in terms of the finding’s generalizability. Accordingly, future studies should investigate the associations observed in the present study relying on more diverse samples, in terms of age, gender, and overall cultural background. Furthermore, the adoption of self-reports at large and their adoption to evaluate MD specifically, including the classification of participants as MDers, introduces potential biases due to their single-informant nature. Future studies should adopt a more robust approach, possibly incorporating the Structured Clinical Interview for Maladaptive Daydreaming (SCIMD; Somer et al., 2017a, b). However, the measure used in our study (MDS-16; Somer et al., 2016a) has proven effective in distinguishing self-identified MDers vs. Non-MDers, with previous research reporting excellent agreement between the SCIMD and MDS-16 (Somer et al., 2017a, b). In this regard, while excluding the minority of participants not meeting the criteria for probable MD is a methodological strength of our study, since it allowed us to perform analysis on a more homogenous sample as regards the evaluation of MD’s function, it nonetheless prevented a comparison between MDers and Non-MDers; this represents a limitation of the study. Additionally, we did not assess the content of participants’ fantasies, limiting a deeper understanding of how and why MD might function as a regulation strategy. Future studies should collect such data to explore the influence and potential differences in ER and psychological symptoms in association with the content and themes of MDers’ fantasies (Brenner et al., 2022). As last, the cross-sectional nature of this study should be duly acknowledged, due to which no causal connections between variables can be assumed. Nonetheless, following Hayes’ approach (Hayes, 2022), since analysis relies on the Ordinary Least Squared (OLS) regression method, the multivariate regressions creating the mediation model serve to assess the association of a criterion variable with the dependent one while controlling for the impact of all others. This approach aids in controlling for the shared variance among the independent variables in the models, allowing for the evaluation of the distinct contribution of each to the dependent one, without implying causal relationships among them. Notwithstanding, longitudinal studies are warranted to deepen the understanding of the temporal association between the investigated dimensions, thus investigating the long-term interplay between MD and both ER and psychological symptoms and well-being. In this regard, the results obtained from the present study, which relied on quite a large sample size (> 200), strengthen and open up the dialogue on MD as a strategy for ER. Accordingly, future researchers could widen the scope of this dialogue by considering in detail the different fantasies that MDers engage in as well as the level of enjoyability and lack of it associated with MD. They could also make appropriate comparisons between MDers and non-MDers across different psychopathological variables to further the investigation of the discussed functional differences (Chirico et al., 2022). In line with this, future research is warranted to investigate the association between ER dimensions—specifically, the difficulty in disengaging attention from negative emotions and the lack of trust in one’s capacity to adaptively self-regulate, which echoes the construct of cognitive control—and MD among MDers. Greater investigation into the interplay between these dimensions and the function of MD could provide valuable insights into the neuro-cognitive-affective mechanisms responsible for the emergence and maintenance of MD. Such insights would hold significant informative value for clinical practice, potentially guiding the development of more effective interventions and therapeutic strategies for individuals struggling with MD. In this regard, future research should also evaluate the efficacy and effectiveness of these interventions, thereby assessing if interventions targeting ER processes can aid in reducing MD and ultimately MDers psychological symptoms.

Implications and conclusions

Albeit the present study findings should be considered tentative waiting for future research to support them, the current study nonetheless holds the potential to be informative and instructive to practitioners for a variety of reasons. Firstly, although MD could be associated with a reduction in negative emotions and psychological symptoms, these effects don’t need to sustain themselves over a long period (Soffer-Dudek & Somer, 2018). Indeed, while MD may bring about a reduction in symptomology while providing a safer context for problems’ evaluation in the short term, it is important to remember that the underlying emotional difficulties persist, with the risk of leading to a long-term rebound effect where symptomology could worsen over time. Practitioners could therefore acknowledge this benefit while also elaborating on the potential for long-term adversity when working with MDers. Moreover, by understanding how the escapism-driven avoidant mechanisms could work for MDers, practitioners could work on substituting this with durable and adaptive ER strategies to provide some long-term benefits to MDers, with the intent of improving treatment outcomes and facilitating more durable and long-term symptom management.

This study therefore adds to an increasing body of literature on MD and puts forth an interesting set of findings that merit further discussion and research from academicians working within this domain. Although our findings don’t fully align with previous research depicting comorbidity, it is important to acknowledge that this field of study is only just emerging, and it is only with ample amounts of research that we will be able to arrive at a holistic understanding of MD and its function.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available; however, they can be available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- DID:

-

Dissociative Identity Disorder.

- ER:

-

Emotion regulation.

- MD:

-

Maladaptive Daydreaming.

- MDer/s:

-

Maladaptive Daydreamer/s (people with MD)

References

Arntz, A., Tiesema, M., & Kindt, M. (2007). Treatment of PTSD: A comparison of imaginal exposure with and without imagery rescripting. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry,38(4), 345–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.10.006

Belavkin, R. V. (2001). In The role of emotion in problem solving (pp. 49–57). C. Johnson.

Bigelsen, J., Lehrfeld, J. M., Jopp, D. S., & Somer, E. (2016). Maladaptive daydreaming: Evidence for an under-researched mental health disorder. Consciousness and Cognition,42, 254–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2016.03.017

Bottesi, G., & Ghisi, M. (2017). La valutazione dell’orientamento negativo al problema: Validazione italiana del Negative Problem Orientation Questionnaire. [Evaluating negative problem orientation: Italian validation of the Negative Problem Orientation Questionnaire]. Psicoterapia Cognitiva e Comportamentale,23(3), 275–290.

Bottesi, G., Ghisi, M., Altoè, G., Conforti, E., Melli, G., & Sica, C. (2015). The Italian version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21: Factor structure and psychometric properties on community and clinical samples. Comprehensive Psychiatry,60, 170–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.04.005

Brenner, R., Somer, E., & Abu-Rayya, H. M. (2022). Personality traits and maladaptive daydreaming: Fantasy functions and themes in a multi-country sample. Personality and Individual Differences,184, 111194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111194

Chirico, I., Volpato, E., Landi, G., Bassi, G., Mancinelli, E., Gagliardini, G., Gemignani, M., Gizzi, G., Manari, T., Moretta, T., Rellini, E., Saltarelli, B., Mariani, R., & Musetti, A. (2022). Maladaptive daydreaming and its relationship with psychopathological symptoms, emotion regulation, and problematic social networking sites use: A network analysis approach. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00938-3

Cludius, B., Mennin, D., & Ehring, T. (2020). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic process. Emotion,20(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000646.supp

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed). L. Erlbaum Associates.

Everaert, J., & Joormann, J. (2019). Emotion regulation difficulties related to depression and anxiety: A network approach to model relations among symptoms, positive reappraisal, and repetitive negative thinking. Clinical Psychological Science,7(6), 1304–1318. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702619859342

Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment,26(1), 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94

Greene, T., West, M., & Somer, E. (2020). Maladaptive daydreaming and emotional regulation difficulties: A network analysis. Psychiatry Research,285, 112799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112799

Griffin, J., & Tyrrell, I. (2014). Why we dream: The definitive answer: how dreaming keeps us sane or can drive us mad. HG Publishing.

Griffiths, M. (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use,10(4), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500114359

Gross, J. J. (2013). Emotion regulation: Taking stock and moving forward. Emotion,13(3), 359–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032135

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Levenson, R. W. (1994). Human emotions: A functional view. In P. Ekman & R. J. Davidson (Eds.), The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions (pp. 123–126). Oxford University Press.

Malmivuori, M.-L. (2006). Affect and self-regulation. Educational Studies in Mathematics,63(2), 149–164.

Miller, E. K., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Review of Neuroscience,24, 167–202. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.167

Mooneyham, B. W., & Schooler, J. W. (2013). The costs and benefits of mind-wandering: A review. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology / Revue Canadienne de Psychologie Expérimentale,67(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031569

Moreira, H., Gouveia, M. J., & Canavarro, M. C. (2022). A bifactor analysis of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale—Short Form (DERS-SF) in a sample of adolescents and adults. Current Psychology,41(2), 757–782. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00602-5

Musetti, A., Franceschini, C., Pingani, L., Freda, M. F., Saita, E., Vegni, E., Zenesini, C., Quattropani, M. C., Lenzo, V., Margherita, G., Lemmo, D., Corsano, P., Borghi, L., Cattivelli, R., Plazzi, G., Castelnuovo, G., Somer, E., & Schimmenti, A. (2021). Maladaptive daydreaming in an adult Italian population during the COVID-19 lockdown. Frontiers in Psychology,12, 631979. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.631979

Pietkiewicz, I. J., Nęcki, S., Bańbura, A., & Tomalski, R. (2018). Maladaptive daydreaming is a new form of behavioral addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions,7(3), 838–843. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.95

Pyszkowska, A., Celban, J., Nowacki, A., & Dubiel, I. (2023). Maladaptive daydreaming, emotional dysregulation, affect and internalized stigma in persons with borderline personality disorder and depression disorder: A network analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy,30(6), 1246–1255. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2923

Ross, C. A., Ridgway, J., & George, N. (2020). Maladaptive daydreaming, dissociation, and the dissociative disorders. Psychiatric Research and Clinical Practice,2(2), 53–61. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.prcp.20190050

Rossi, A. A., Panzeri, A., & Mannarini, S. (2023). The Italian Version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale– Short Form (IT-DERS-SF): A two-step validation study. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment,45(2), 572–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-022-10006-8

Salomon-Small, G., Somer, E., Harel-Schwarzmann, M., & Soffer-Dudek, N. (2021). Maladaptive daydreaming and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: A confirmatory and exploratory investigation of shared mechanisms. Journal of Psychiatric Research,136, 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.02.017

Sándor, A., Bugán, A., Nagy, A., Bogdán, L. S., & Molnár, J. (2023). Attachment characteristics and emotion regulation difficulties among maladaptive and normal daydreamers. Current Psychology,42(2), 1617–1634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01546-5

Schäfer, J. Ö., Naumann, E., Holmes, E. A., Tuschen-Caffier, B., & Samson, A. C. (2017). Emotion regulation strategies in depressive and anxiety symptoms in youth: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Youth and Adolescence,46(2), 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0585-0

Schimmenti, A., Sideli, L., La Marca, L., Gori, A., & Terrone, G. (2020). Reliability, validity, and factor structure of the Maladaptive Daydreaming Scale (MDS–16) in an Italian sample. Journal of Personality Assessment,102(5), 689–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2019.1594240

Singer, J. L. (1975). The inner world of daydreaming (1st ed). Harper & Row.

Sloan, E., Hall, K., Moulding, R., Bryce, S., Mildred, H., & Staiger, P. K. (2017). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic treatment construct across anxiety, depression, substance, eating and borderline personality disorders: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review,57, 141–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.09.002

Soffer-Dudek, N., & Theodor-Katz, N. (2022). Maladaptive daydreaming: Epidemiological data on a newly identified syndrome. Frontiers in Psychiatry,13, 871041. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.871041

Soffer-Dudek, N., & Somer, E. (2018). Trapped in a daydream: Daily elevations in maladaptive daydreaming are associated with daily psychopathological symptoms. Frontiers in Psychiatry,9, 194. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00194

Soffer-Dudek, N., & Somer, E. (2023). Maladaptive daydreaming is a dissociative disorder: Supporting evidence and theory. In M. J. Dorachi, S. N. Gold, & J. A. O'Neil (Eds.), Dissociation and the dissociative disorders: Past, present, future (2nd ed., pp. 547–563). Routledge.

Soffer-Dudek, N., Somer, E., Abu-Rayya, H. M., Metin, B., & Schimmenti, A. (2020). Different cultures, similar daydream addiction? An examination of the cross-cultural measurement equivalence of the Maladaptive Daydreaming Scale. Journal of Behavioral Addictions,9(4), 1056–1067. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00080

Somer, E. (2002). Maladaptive daydreaming: A qualitative inquiry. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy,32(2/3), 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020597026919

Somer, E. (2018). Maladaptive daydreaming: Ontological analysis, treatment rationale; a pilot case report. Frontiers in the Psychotherapy of Trauma and Dissociation,1, 1–22.

Somer, E., & Herscu, O. (2017). Childhood trauma, social anxiety, absorption and fantasy dependence: Two potential mediated pathways to maladaptive daydreaming. Journal of Addictive Behaviors, Therapy & Rehabilitation,06. https://doi.org/10.4172/2324-9005.1000170

Somer, E., Lehrfeld, J., Bigelsen, J., & Jopp, D. S. (2016a). Development and validation of the Maladaptive Daydreaming Scale (MDS). Consciousness and Cognition,39, 77–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2015.12.001

Somer, E., Somer, L., & Jopp, D. S. (2016b). Childhood antecedents and maintaining factors in maladaptive daydreaming. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease,204(6), 471–478. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000507

Somer, E., Soffer-Dudek, N., & Ross, C. A. (2017a). The comorbidity of daydreaming disorder (maladaptive daydreaming). Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease,205(7), 525–530. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000685

Somer, E., Soffer-Dudek, N., Ross, C. A., & Halpern, N. (2017b). Maladaptive daydreaming: Proposed diagnostic criteria and their assessment with a structured clinical interview. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice,4(2), 176–189. https://doi.org/10.1037/cns0000114

Somer, E., Abu-Raya, H. M., & NsairySimaan, Z. (2019). Maladaptive daydreaming among recovering substance use disorder patients: Prevalence and mediation of the relationship between childhood trauma and dissociation. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction,17(2), 206–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-0011-9

Telch, M. J., Cobb, A. R., & Lancaster, C. L. (2014). Exposure therapy. In P. Emmelkamp & T. Ehring (Eds.), The Wiley Handbook of Anxiety Disorders (1st ed., pp. 715–756). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118775349.ch35

Thomson, P., & Jaque, V. (2023). Maladaptive daydreaming, overexcitability, and emotion regulation. Roeper Review,45(3), 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783193.2023.2212634

West, M. J., & Somer, E. (2020). Empathy, emotion regulation, and creativity in immersive and maladaptive daydreaming. Imagination, Cognition and Personality,39(4), 358–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276236619864277

Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and reality. Routledge.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Padova within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. The study received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Sara Spisto, Elisa Mancinelli, Silvia Salcuni; Data Collection: Sara Spisto; Methodology: Elisa Mancinelli; Formal analysis: Elisa Mancinelli; Writing—original draft preparation: Sara Spisto, Vinay Jagdish Sukhija; Writing—review and editing: Vinay Jagdish Sukhija, Elisa Mancinelli; Supervision: Silvia Salcuni.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed consent

Participants were informed that participation was voluntary, and data were collected autonomously. They were also informed that they could withdraw from the study at any moment, without providing an explanation for it and without incurring in any type of consequence.

Research involving human participants

The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Interdepartmental Ethical Committee of the University of Padova (No. 4778/2022).

Conflicts of interest

None to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mancinelli, E., Spisto, S., Sukhija, V.J. et al. Maladaptive daydreaming as emotion regulation strategy: exploring the association with emotion regulation, psychological symptoms, and negative problem-solving orientation. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06487-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06487-3