Abstract

Psychological Flexibility is an essential concept in Contextual Behavioural Sciences. The development of instruments is vital for its study, and it is an opportunity to reflect on this concept. Among the measures of this construct, Psy-Flex shows promise due to comprehensiveness in assessing the six facets of psychological flexibility and its pragmatic value. In the present study, we sought to translate Psy-Flex to Portuguese and adapt it transculturally for use in Portugal and Brazil. The translation was done independently by Brazilian and Portuguese researchers, and a consensus procedure was done to identify a synthesis. A total of 873 adults from Portugal and Brazil were involved in this study. The participants completed several questionnaires with ACT-related measures (e.g., cognitive fusion, mindful attention) and instruments measuring conceptually related variables (e.g., positive mental health). The results show good psychometric properties of PsyFlex. The one-factor structure of the original instrument was confirmed in both the Portuguese and Brazilian samples. Confirmatory factor analysis revealed a good fit of the model to the data (CFI = 0.985, RMSEA = 0.055) of both countries. Furthermore, the Psy-Flex showed convergent validity with related measures in a conceptually expected way. As a transcultural instrument, we argue that both the similarities and differences across samples suggest the broad human nature of psychological flexibility while retaining its context sensitivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Psychological Flexibility (PF) is the “ability to contact the present moment more fully as a conscious human being, and to change or persist in behaviour when doing so serves valued ends” (Hayes et al., 2006, p. 6). PF constitutes a pivotal facet of overall health and well-being (Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010; Gloster et al., 2017; Hayes et al., 2006).

Within the theoretical framework of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), six interrelated processes collectively facilitate psychological flexibility. Namely: (1) Acceptance, (2) cognitive defusion, (3) present moment, (4) self-as-context, (5) committed action, and (6) values (Hayes et al., 2006). Acceptance promotes openness and willingness to embrace thoughts and feelings instead of experiential avoidance. Cognitive defusion pertains to the transformation of functions of thought, changing how individuals interact with them. Mindfulness involves a state of acute present moment with a non-judgemental attitude. Self as context refers to the idea that the Self emerges with a stable sense of identity, making an individual aware of his flow of experiences without attaching to them. Values are chosen qualities of intentional action. Finally, Committed Action refers to engaging in behaviours coordinated with the qualities of action described in chosen values (Hayes et al., 2006, 2012). These core psychological flexibility processes are superimposed and interrelated, not an end in themselves, but a way to reach a life that is more conscious and consistent with one’s values (Gloster et al., 2020; Hofer et al., 2018). These processes synergistically reinforce each other, collectively striving to amplify psychological flexibility (Hayes et al., 2006).

By contrast, Psychological Inflexibility (PI) refers to getting stuck in undesirable inner experiences using avoidance strategies to lessen the associated distress. These strategies result in difficulties in understanding contextual contingencies and behaving congruently with one’s values and goals (Bond et al., 2011). While psychological flexibility is closely linked to psychological well-being, conversely, PI has been consistently associated with elevated rates of psychopathology (Fairburn et al., 2003; Gilbert, 2019; Gloster et al., 2017; Goldstone et al., 2011; Hayes et al., 2006; Levin et al., 2014; Meyer et al., 2019; Rawal et al., 2010; Tavakoli et al., 2019; Venta et al., 2012).

Assessment of psychological flexibility

Over the last decades, psychological flexibility has gained significant attention in clinical psychology, prompting studies utilizing psychological flexibility as a metric of therapeutic change (e.g., Hayes et al., 2022). Several instruments were developed with this purpose, yet psychometric robustness has been criticized (Kashdan et al., 2020; Tyndall et al., 2019; Vaughan-Johnston et al., 2017; Wolgast, 2014). A recurring critique revolves around the inadequate coverage of all relevant domains, the absence of temporal reference points, and a lack of contextual specificity. As psychological flexibility is a context-sensitive dimension, the measure should be sensitive to a person’s context rather than treating it as a trait (Gloster et al., 2021; Tyndall et al., 2019; Wolgast, 2014).

Gloster et al. (2021) created the Psy-Flex, an instrument comprised of six items that reflect context-depend measures of each of the six components of psychological flexibility. Gloster et al. demonstrated that psychological flexibility predicts mental well-being in clinical and non-clinical samples, underscoring the utility and robustness of the measure (Gloster et al., 2021). In addition, the factorial analysis of the scale showed only one-factor solution that is consistent with the existing theoretical framework (Hayes et al., 2012; Jo et al., 2023; Gur et al., 2024).

An effort to provide psychometrics evidence for psychological flexibility measures across different languages is critical. Many studies have assessed psychological flexibility and related constructs in the Portuguese language, both in Portugal and Brazil (e.g., Barbosa & Murta, 2015; Lucena-Santos et al., 2015 for a review). Portugal and Brazil have had the same native language and unified Portuguese orthography since 2009. Although cultural differences determine the use of different words for the same referent or particular words that are used specifically in one country and not the other, transcultural adaptation of psychometric measures has been done for both Portuguese and Brazilian populations (e.g., Marôco et al., 2014).

The American Psychological Association (APA) underscores the crucial significance of incorporating adaptation and a comprehensive understanding of cultural differences in psychological interventions (APA, 2006). Behavior can only be comprehended when viewed within its specific context. Numerous psychological concepts are developed in particular cultural settings, prompting the essential need to question the validation of these widely accepted constructs and their applicability in other contexts (Borgogna et al., 2020; Gloster et al., 2020).

Present study

The present study sought to adapt and transculturally validate a unique Psy-Flex scale in a Portuguese and Brazilian sample. We sought to confirm the unifactorial structure identified by the original authors and confirmed in subsequent adaptations. Secondly, we aimed to validate PsyFlex by studying its association with another instrument of psychological flexibility and conceptually related variables (i.e., mindfulness, experiential avoidance, cognitive fusion and mental health). Transcultural validation is indispensable for refining the measurement tool and ensuring its applicability across different nationalities.

Until now, few studies have been conducted validating a common and unique Portuguese scale for Portugal and the Brazilian population (e.g., Marôco et al., 2014). This provides a valid instrument of psychological flexibility for a language spoken by over 200 million people worldwide. The application of the same instrument, adapted to Portuguese in a transcultural manner, allows studying psychological flexibility across cultures to help understand what is cross-cultural and context-specific.

Method

Design

The present study is a cross-sectional examination of the psychometric properties of the Psy-Flex instrument after its cultural adaptation for use with adults in Portugal and Brazil. This instrument’s reliability is assessed, aiming to confirm its original factorial structure, and validity is assessed through association with conceptually related instruments comparatively between two culturally distinct samples. The choice of the instruments was to provide a comparison with the original study (Gloster et al., 2021).

Participants

The data for this study was collected from two community samples in Portugal and Brazil. Since the aim was to obtain a diverse sample, only being less than 18 years old and the inability to fill out the self-reports were the excluding criteria. 873 adults participated in this study, of which 213 spoke European Portuguese while 660 spoke Brazilian Portuguese. The participants were mostly women, with an average age of 36 (DP = 12.8). Table 1 presents the characteristics of both samples. There were no statistical differences apart from education level [c2 (3, N = 873) = 27,39, p <.001] and marital status [c2 (3, N = 873) = 27,162, p <.001].

The participants came from several districts in Portugal – Lisboa 112 (50.4%), Setúbal 32 (14.4%), Porto 18 (8,1%), Other 60 (27.0%) – and several states in Brazil - São Paulo 178 (28.3%), Minas Gerais 65 (10.3%), Espírito Santo 63 (10.0%), Rio de Janeiro 60 (9.5%), Other 264 (41.9%). This was a convenience sample. These distributions are similar but do not match both countries’ demographic distributions.

Translation and cultural adaptation of Psy-Flex

The Psy-Flex scale was translated independently by two researchers from Portugal and two from Brazil – authors of the current paper. These are senior researchers and clinicians with training in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Despite sharing a common orthography, some usage differences influence understanding. The researchers were asked to translate the English version of PsyFlex in a manner that was sensitive to Portuguese usage in each country. The divergences between versions were consensually resolved to balance spelling and language use. One item was difficult to translate because there was no good Portuguese version of the expression “a steady core”. The authors consensualized the expression that best denoted the concept. The final version was back-translated by a portuguese professional translator, leading to further refinements. After this process, the instrument was piloted, confirming that individuals in both countries easily understood it.

The final version of the items are as follows: (1) Mesmo que os meus pensamentos me levem para outro lugar, em momentos importantes eu consigo focar no que está acontecendo à minha volta (estar presente) [Even if I am somewhere else with my thoughts, I can focus on what’s going on in important moments (being present)], (2) Se necessário, posso deixar que pensamentos e experiências desagradáveis aconteçam sem ter que me livrar deles imediatamente (abertura a experiência) [If need be, I can let unpleasant thoughts and experiences happen without having to get rid of them immediately (Being open for experiences)], (3) Eu consigo observar pensamentos difíceis à distância, sem deixar que eles me controlem (defusão cognitiva) [I can look at hindering thoughts from a distance without letting them control me (Leaving thoughts be)], (4) Mesmo que pensamentos e experiências me confundam, eu consigo reconhecer uma parte importante de mim que não se altera (self como contexto) [Even if thoughts and experiences are confusing me I can notice something like a steady core inside of me (Steady self)], (5) Eu determino o que é importante para mim e decido onde quero usar a minha energia (consciência dos próprios valores) [I determine what’s important for me and decide what I want to use my energy for (Awareness of one’s own values)], & (6) Envolvo-me completamente em coisas que são importantes, úteis ou significativas para mim (compromisso) [I engage thoroughly in things that are important, useful, or meaningful to me (Being engaged)]. The labels for the Likert scale are 1 very seldom(pouco frequente) to 5 very often (muito frequente). Just as in the original scale, higher scores represent higher levels of psychological flexibility.

Instruments

Comprehensive Assessment of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Processes (CompACT)

CompACT (Francis et al., 2016) measures Psychological Flexibility with 23 items. This instrument is divided into three subscales: openness to experience, awareness of behaviour and valued action. In this study, the Portuguese transcultural adaptation of CompACT (Trindade et al., 2021) for both the Portuguese sample from Portugal and the Portuguese sample from Brazil. The instrument demonstrated high internal consistency in both English speaker samples. Portuguese from Portugal in the subscales. In the present study, the scale presented acceptable internal consistency for both Portugal (α = 0.85) and Brazil (α = 0.89). The same is true for the subscales: awareness of behaviour [Portugal (α = 0.88) and Brazil (α = 0.88)], valued action [Portugal (α = 0.86) and Brazil (α = 0.91)] and openness to experience [Portugal (α = 0.74) and Brazil (α = 0.79)].

Mindful Attention and Awareness (MAAS)

The MAAS (Brown & Ryan, 2003) is a 15-item questionnaire that aims to measure the level of mindfulness, namely the attention and awareness in individuals’ daily lives. Items are rated from 1 (“almost always”) to 4 (“almost always”). Never”). We used the two available versions of the instrument - the Portuguese (Gregório & Pinto-Gouveia, 2013) and the Brazilian adaptation (Barros et al., 2015) according to the chosen dialect. The instrument demonstrated high internal consistency in both samples of Portuguese speakers. In the present study, the scale presented acceptable internal consistency for both Portugal (α =.92) and Brazil (α =.90).

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ-II)

The AAQ-II (Bond et al., 2011) is a 7-item questionnaire that assesses experimental avoidance and psychological inflexibility. The items range from 1 (“never true”) to 7 (“always true”). The present study used the Portuguese (Dinis et al., 2012) and Brazilian (Barbosa & Murta, 2015) versions. The instrument demonstrated a consistency high internal in both samples of speakers of Portuguese from Portugal and Portuguese from Brazil. In the present study, the scale presented acceptable internal consistency for both Portugal (α = 0.93) and Brazil (α = 0.94).

Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire (CFQ-7)

The CFQ-7 (Gillanders et al., 2014) is a 7-item questionnaire which assesses cognitive fusion. Items are rated on a scale ranging from 1 (“never true”) to 7 (“always true”). This study used the Portuguese (Pinto-Gouveia et al., 2020) and Brazilian (Peixoto et al., 2019) versions of CFQ-7. The instrument demonstrated high internal consistency in both original adaptations. In the present study, the scale presented acceptable internal consistency for both Portugal (α = 0.95) and Brazil (α = 0.94).

Mental Health Continuum Short Form (MHC-SF)

The MHC-SF (Lamers et al., 2011) is widely used to measure well-being, consisting of 14 items. Each item evaluates the frequency of the duration of each statement during the past month on a scale of 0 (“never”) to 5 (“almost every day”). Affirmations include emotional, social and psychological aspects of well-being. The present study used the Portuguese (Fonte et al., 2020) and Brazilian (Machado & Bandeira, 2015) adaptations of the MHC-SF. The instrument demonstrated high internal consistency in both samples of Portuguese speakers from Portugal in the l. In the present study, the scale presented acceptable internal consistency for both Portugal (α = 0.92) and Brazil (α = 0.92). The same is true for the subscales: emotional [Portugal (α = 0.86) and Brazil (α = 0.88)], social [Portugal (α = 0.84) and Brazil (α = 0.80)] and psychological [Portugal (α = 0.88) and Brazil (α = 0.85)].

Depression, Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21)

The DASS-21 (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) measures psychopathology, namely depression, anxiety and stress. The scale has 21 items and has been widely used. Items are rated on a frequency scale from 0 (“not applicable”) to 3 (“applied most of the time”) in which each statement occurred in the last week. The items may refer to the depression, anxiety, and stress subscales. The Portuguese adaptation (Ribeiro et al., 2004) and the Brazilian adaptation (Vignola, 2013) were used in the present study. The instrument demonstrated high internal consistency in both samples. In the present study, the scale presented acceptable internal consistency for depression [Portugal (α = 0.90) and Brazil (α = 0.90)], anxiety [Portugal (α = 0.87) and Brazil (α = 0.87)] and stress [Portugal (α = 0.91) and Brazil (α = 0.87)].

Procedure

Ethical committees in both countries approved the study. In Brazil, it was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee at Mackenzie Presbyterian University and by the National Research Ethics Committee (SISNEP, Brazil; CAAE n° 68059923.7.0000.0084). In Portugal, the study was approved by the Ethical Committee of ISPA - Instituto Unversitário (Nº I-108-3-23). All participants gave written informed consent, and the original authors of Psy-Flex gave the necessary permissions.

The study protocol was administered and disseminated online through emails, social networks, and contact networks. Paid advertisements in social networks were used both in Portugal and Brazil. In these advertisements, no other variable (other than country and age above 18) was used to select the population target. The study questionnaire was created in Qualtrics. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study and gave informed consent before completing the questionnaire. Participants choose which dialect they speak - Portuguese from Portugal or Brazil. Apart from Psy-Flex and CompACT, which have transcultural versions, there were two versions of the protocol. In each version, the instruments were adapted to each of the participants’ dialects. The order of the application of the instruments was random. The questionnaire was administered using Qualtrics.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated to inspect the data, including averages and standard deviations. To test the hypothesis of unifactoriality, we used Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Cronbach’s alphas to study the internal structure of the scale. T-tests were used to compare samples and Pearson correlations to test linear relationships with other variables. For all analyses, an α ≤ 0.05 was considered. We conducted all analyses in SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 28.0 for Windows and AMOS v.24.

Results

Samples characteristics

Table 2 compares the two samples concerning the self-reports used in this research. Contrasting our samples with those of the original study (Gloster et al., 2021), our sample presented higher scores on the Psy-Flex [(22.3 vs. 20.4), t(1446.63) = -9.45, p <.001]. Furthermore, the Portuguese sample scored significantly but slightly higher in the current study. The first, second and third quartile are the following for Portugal − 21.0 (Q1), 24.0 (Q2), 25.0 (Q3) – and Brazil – 20.0 (Q1), 22.0 (Q2), 24.0 (Q3). Concerning the relationship between psychological flexibility and gender, no differences were found between males (M = 22.6; SD = 3.51) and females (M = 22.1; SD = 3.57), t(849) = 1.905, p =.057. For the remaining variables, the differences were also minor.

Item analysis

The descriptive statistics for the six items of Psy-Flex are presented in Table 3. The median values are above the scale’s medium value (3, p <.001). This suggests a general elevated psychological flexibility in community samples.

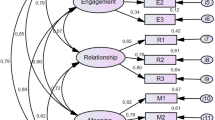

Factor structure

The structural analysis of the original unifactorial model of Psy-Flex was conducted through Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). We obtained a good quality of adjustment: χ2/df = 3.601; CFI = 0.985; GFI = 0.982; RMSEA = 0.055, SRMR = 0.023. The adjustment implied the correlation of errors 1 and 2, 2 and 3 and 1 and 4 (Fig. 1).

The model adjusted simultaneously for the two samples showed to be adequate: c2/gl = 2.855; CFI = 0.979; GFI = 0.988, TLI = 0.946; RMSEA = 0.046; IC90% RMSEA ]0.028; 0.065[. The analysis of invariance of the factorial refined model, assuming the same structure for both samples (configurational invariance), did not show the existence of differences between the factorial weights of the two countries [Dc2 (5) = 3.129; p =.680], in the correlations [Dc2 (1) = 0.181; p =.670] and the residuals [Dc2 (9) = 18.730; p =.028]. However, the averages (intercepts) of items significantly differ in both countries [Dc2 (6) = 116.201; p <.001] (Fig. 2).

The internal consistency of the Psy-Flex scale, measured by Cronbach’s alpha, was α = 0.743 (acceptable). This value would not improve significantly if any of the six items were removed. The results were similar for the two samples, with the Portuguese sample having an α = 0.75 and the Brazilian sample an α = 0.74.

Convergent validity

The correlation between Psy-Flex for Brazil and Portugal shows the same pattern of results. Correlations are positive and moderate (> 0.4) with Comprehensive Assessment of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (and its dimensions), Acceptance and Action Questionnaire, Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire e Depression, and Mental Health Continuum Short-Form. Correlations are positive and weak with Mindful Attention and Awareness. Correlations are negative and moderate with the scales of the Anxiety Stress Scale. These relations are according to what is theoretically expected. A high flexibility is linked with a higher acceptance, mindful attention and awareness and positive mental health. Additionally, it has a negative relation with cognitive fusion and psychopathology (Table 4).

Discussion

The first goal of this study was to adapt Psy-Flex to Portuguese in a transcultural manner. This goal also allowed a comparison of the instruments between Portugal and Brazil and a reflection on psychological flexibility across cultures. We obtained a version of the instrument with good internal consistency and the original one-factor structure (Gloster et al., 2021) for both the Portuguese and Brazilian samples. This is similar to the existing adaptations of the instrument (Jo et al., 2023; Yıldırım & Aziz, 2023).

For both samples, there was evidence of convergent validity with CompACT and its subscales. Psycflex is also related to other measures of concepts associated with psychological flexibility (experiential avoidance, cognitive fusion, mindful attention) in a manner that is theoretically expected. Correlations ranged from weak to moderate, suggesting that despite the existence of an association, the concepts do not overlap and have distinctive values. Finally, Psy-Flex was positively associated with positive mental health and negatively associated with psychopathology - both measured negatively and positively. This follows previous literature suggesting a relationship between psychological flexibility and mental health (e.g., Tavakoli et al., 2019). These results support the validity of the instrument in measuring psychological flexibility, and they are similar to those of the original research on the instrument (Gloster et al., 2021) and adaptations (Jo et al., 2023; Yıldırım & Aziz, 2023). This study reinforces Psy-Flex as a valid and pragmatic instrument for measuring psychological flexibility.

The comparison of two samples of two countries sharing a language allows for the consideration of psychological similarities and differences across cultures. The two samples were somewhat different on several instruments, with the sample from Portugal having slightly higher values in positive constructs – such as psychological flexibility and positive mental health. However, the factorial structure of Psy-Flex remained the same in both samples, and the relations with other variables followed the same pattern of associations. The unifactoriality was observed in the adaptations of the instruments done so far. In the present study, comparing two culturally different contexts sharing the same language, this uniformity is informative. It suggests that psychological flexibility is a cross-cultural human set of skills relevant across cultures that are associated with well-being and human flourishing. Future research may expand this exploration of the cross-cultural and culture-specific dimensions of psychological flexibility and how it is embedded in specific contexts – culturally or otherwise.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, despite being varied in several demographic variables, notably place of residence, the samples were not representative of either country. This opens the possibility of bias and limits the scope of comparison between samples and with other studies. Future studies using representative samples have the potential to have higher external validity and to control the role of demographics like education level or age. Secondly, like in similar studies, the samples overrepresent females and individuals with higher education levels. This was true for both samples; in both countries, it would be important to study males and individuals of more unfavourable backgrounds. Exploring distinct social contexts within a specific national culture is just as crucial as studying different cultures. This exploration could entail the identification of cultural determinants or moderators of psychological flexibility. Furthermore, studying interventions or societal events (e.g., economic crises) could further enhance our understanding of this relevant process.

Psy-Flex is confirmed to be a valid and valuable tool for studying psychological flexibility. Clinically, this concept is important in accessing the client’s strengths and resources and in bridging with interventions that foster the elements assessed in this instrument – being present, open to experience, and contextual endless of self. It can, therefore, be used in initial assessments and triage but also as a link with intervention. This study also shows psychological flexibility as essential in understanding well-being and flourishing across cultures. Translating Hayes and Pistorello (2015, p.26), “Such diversity is even more obvious when all the communities of Portuguese-speaking countries are considered. Two of the most important features of third-generation methods are that they are much more contextual and focused on principles and processes directed at people, their problems, and their pursuit of happiness rather than disorders. This focus makes it easier to imagine ways to overcome the cognitive and behavioural division”. This study was a step in this direction.

Data sharing

Data is available in a public repository (Open science framework) - DOI https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/ZHTBV.

Data availability

Data is available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

American Psychological Association, Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice. (2006). Evidence- based practice in psychology. American Psychologist, 61(4), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.4.271

Barbosa, L. M., & Murta, S. G. (2015). Acceptance and commitment therapy: History, fundamentals, model and evidence. Brazilian Journal of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy, 16(3), 34–49. https://doi.org/10.31505/rbtcc.v16i3.711

Barros, V. V. D., Kozasa, E. H., Souza, I. C. W. D., & Ronzani, T. M. (2015). Validity evidence of the Brazilian version of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 28, 87–95.

Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. M., Guenole, N., Orcutt, H. K., et al. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the acceptance and action questionnaire–II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 676–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.Beth.2011.03.007

Borgogna, N. C., McDermott, R. C., Berry, A., Lathan, E. C., & Gonzales, J. (2020). A multicultural examination of experiential avoidance: AAQ– II measurement comparisons across Asian American, Black, Latinx, Middle Eastern, and White college students. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 16, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.01.011

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848.

Dinis, A., Pinto-Gouveia, J., Xavier, A., & Gregório, S. (2012). Experiential avoidance in clinical and non-clinical samples: AAQ-II Portuguese version. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 12(2), 139–156.

Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Shafran, R. (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A transdiagnostic theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(5), 509–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(02)00088-8

Fonte, C., Silva, I., Vilhena, E., & Keyes, C. L. (2020). The Portuguese adaptation of the mental health continuum-short form for adult population. Community Mental Health Journal, 56(2), 368–375.

Francis, A. W., Dawson, D. L., & Golijani-Moghaddam, N. (2016). The development and validation of the Comprehensive assessment of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy processes (CompACT). Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 5(3), 134–145.

Gilbert, P. (2019). Psychotherapy for the 21st century: An integrative, evolutionary, contextual, biopsychosocial approach. Psycholology & Psychotherapy: Theory Research & Practice, 92, 164–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12226

Gillanders, D. T., Bolderston, H., Bond, F. W., Dempster, M., Flaxman, P. E., Campbell, L., et al. (2014). The development and initial validation of the cognitive fusion questionnaire. Behavior Therapy, 45(1), 83–101.

Gloster, A. T., Meyer, A. H., & Lieb, R. (2017). Psychological flexibility as a malleable public health target: Evidence from a representative sample. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 6(2), 166–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2017.02.003

Gloster, A. T., Walder, N., Levin, M. E., Twohig, M. P., & Karekla, M. (2020). The empirical status of acceptance and commitment therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18, 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.09.009

Gloster, A. T., Block, V. J., Klotsche, J., Villanueva, J., Rinner, M. T., Benoy, C., … & Bader, K. (2021). Psy-Flex: A contextually sensitive measure of psychological flexibility. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 22, 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2021.09.00

Goldstone, E., Farhall, J., & Ong, B. (2011). Life hassles, experiential avoidance and distressing delusional experiences. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49, 260–266.

Gregório, S., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2013). Mindful attention and awareness: Relationships with psychopathology and emotion regulation. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 16, E79.

Gur, A., Mouadeb, D., Reich, A., & Atar, L. (2024). Translation and psychometric evaluation of the Hebrew version of psy-flex to assess psychological flexibility. Journal of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapy, 34(1), 100483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbct.2023.100483

Hayes, S. C., & Pistorello, J. (2015). Prefácio: A terceira geração da terapia cognitiva e comportamental no brasil e nos demais países de língua portuguesa. In P. Lucena-Santos, J. Pinto-Gouveia, & M. S. Oliveira (Eds.), Terapias Comportamentais de Terceira Geração: Guia para Profissionais (pp. 21–27). Sinopsys Editora.

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behavior Research and Therapy, 44, 1–25.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy. The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

Hayes, S. C., Ciarrochi, J., Hofmann, S. G., Chin, F., & Sahdra, B. (2022). Evolving an idionomic approach to processes of change: Towards a unified personalized science of human improvement. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 156, 104155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2022.104155

Hofer, P. D., Waadt, M., Aschwanden, R., Milidou, M., Acker, J., Meyer, A. H., Lieb, R., & Gloster, A. T. (2018). Self-help for stress and burnout without therapist contact: An online randomized controlled trial. Work & Stress, 32(2), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2017.1402389

Jo, D., Seong, B., & Yang, E. (2023). Psychometric properties of the psy-flex scale: A validation study in a community sample in Korea. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 2023(30), 70–79.

Kashdan, T. B., & Rottenberg, J. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 865–878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.001

Kashdan, T. B., Disabato, D. J., Goodman, F. R., Doorley, J. D., & McKnight, P. E. (2020). Understanding psychological flexibility: A multimethod exploration of pursuing valued goals despite the presence of distress. Psychological Assessment, 32(9), 829–850. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000834

Lamers, S. M. A., Westerhof, G. J., Bohlmeijer, E. T., Klooster, T., & Keyes, C. L. M. (2011). Evaluating the psychometric properties of the mental health Continuum Short Form (MHC-SF). Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(1), 99–110.

Levin, M. E., Maclane, C., Daflos, S., Seeley, J. R., Hayes, S. C., Biglan, A., & Pistorello, J. (2014). Examining psychological inflexibility as a transdiagnostic process across psychological disorders. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 3(3), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2014.06.003

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 335–343.

Lucena-Santos, P., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Oliveira, M. S. (2015). Primeira, Segunda e Terceira Geração de Terapias Comportamentais. In P. Lucena-Santos, J. Pinto-Gouveia, & M. S. Oliveira (Eds.), Terapias comportamentais de terceira geração: Guia para profissionais (pp. 29–58). Sinopsys.

Machado, W. D. L., & Bandeira, D. R. (2015). Positive mental health scale: Validation of the mental health continuum-short form. Psico-Usf, 20, 259–274.

Marôco, J. P., Campos, J. A. D. B., Vinagre, M. D. G., & Pais-Ribeirod, J. L. (2014). Adaptação transcultural Brasil-Portugal da escala de Satisfação com o Suporte Social para estudantes do ensino superior [Brazil-Portugal transcultural adaptation of the Social Support Satisfaction Scale for college students]. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 27(2), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-7153.201427205

Meyer, E. C., Kotte, A., Kimbrel, N. A., DeBeer, B. B., Elliott, T. R., Gulliver, S. B., & Morissette, S. B. (2019). Predictors of lower-than-expected posttraumatic symptom severity in war veterans: The influence of personality, self-reported trait resilience, and psychological. Behavior Research and Therapy, 113, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.12.005

Peixoto, E. M., Honda, G. C., Gagnon, J., de Cássia Nakano, T., da Rocha, G. M. A., Zanini, D. S., & Balbinotti, M. A. A. (2019). Questionário De Fusão Cognitiva (CFQ): Novas evidências de validade e invariância transcultural. Psico, 50(1), e27851.

Pinto-Gouveia, J., Dinis, A., Gregório, S., & Pinto, A. M. (2020). Concurrent effects of different psychological processes in the prediction of depressive symptoms–The role of cognitive fusion. Current Psychology, 39(2), 528–539.

Rawal, A., Park, R. J., & Williams, J. M. (2010). Rumination, experiential avoidance, and dysfunctional thinking in eating disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(9), 851–859. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.009

Ribeiro, J. L. P., Honrado, A. A. J. D., & Leal, I. P. (2004). Contribuição para o estudo da adaptação portuguesa das escalas de ansiedade, depressão e stress (EADS) de 21 itens de Lovibond e Lovibond. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças (pp. 2229–239).

Tavakoli, N., Broyles, A., Reid, E. K., Sandoval, J. R., & Correa-Fernández, V. (2019). Psychological inflexibility as it relates to stress, worry, generalized anxiety, and somatization in an ethnically diverse sample of college students. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 11, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2018.11.001

Trindade, I. A., Ferreira, N. B., Mendes, A. L., Ferreira, C., Dawson, D., & Golijani-Moghaddam, N. (2021). Comprehensive assessment of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy processes (CompACT): Measure refinement and study of measurement invariance across Portuguese and UK samples. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 21, 30–36.

Tyndall, I., Waldeck, D., Pancani, L., Whelan, R., Roche, B., & Dawson, D. L. (2019). The Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II) as a measure of experiential avoidance: Concerns over discriminant validity. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 12, 278–284.

Vaughan-Johnston, T. I., Quickert, R. E., & MacDonald, T. K. (2017). Psychological flexibility under fire: Testing the incremental validity of experiential avoidance. Personality and Individual Differences, 105, 335–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.10.011

Venta, A., Sharp, C., & Hart, J. (2012). The relation between anxiety disorder and experiential avoidance in inpatient adolescents. Psychological Assessment, 24, 240–248.

Vignola, R. C. B. (2013). Escala de depressão, ansiedade e estresse (DASS): Adaptação e validação para o português do Brasil. Master dissertation in psychology. Available at: http://repositorio.unifesp.br/handle/11600/48328

Wolgast, M. (2014). What does the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ-II) really measure? Behavior Therapy, 45(6), 831–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2014.07.002

Yıldırım, M., & Aziz, I. A. (2023). Turkish validation of the psy-flex scale and its association with resilience and social support. Environment and Social Psychology, 8(1), 1513. https://doi.org/10.18063/esp.v8.i1.1513

Funding

Open access funding provided by FCT|FCCN (b-on). The present research had no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Neto, D.D., Mouadeb, D., Lemos, N. et al. Contextual similarities in psychological flexibility: the Brazil-Portugal transcultural adaptation of Psy-Flex. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06241-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06241-9