Abstract

Scientific literature has revealed that there are gender differences in aspects related to mental health. These differences are especially evident in the higher prevalence of emotional disorders (EDs) in women, the greater severity of some clinical variables and symptoms and, also, in the response to psychological treatment. The Unified Protocol (UP) is a transdiagnostic treatment specially designed to address EDs with growing evidence about its cost-effectiveness. The aim of this study is to analyze gender differences in clinical variables and the response to UP treatment applied in a group format. The sample consisted of 277 users (78.3% women) of the Spanish specialized public mental health system, all of them with a diagnosis of EDs. Depressive and anxiety symptomatology, neuroticism, extraversion, interference and quality of life were assessed at baseline, post-treatment, and at 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-ups. We found a statistically significant differences between men and women in severity of depressive and anxious symptomatology, with women presenting the highest scores at the beginning of the treatment. After the intervention, these differences were reduced until no statistically significant differences were found in any of the variables over the 12-month follow-up. The results of this study support the creation of gender-heterogeneous UP groups in the public mental health system for the transdiagnostic treatment of people with EDs. Trial NCT03064477 (March 10, 2017).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that gender is a central factor in people's health, since both biological and social factors determine the disease process of men and women (WHO, 2009). Different hypotheses have been put forward to explain these gender differences, from more biological aspects (X-linked genetic transmission, female endocrine physiology, etc.) to psychosocial factors (e.g. stress or social status, among others) (Aznar et al., 2003). However, it is suggested that both biological and environmental factors are interrelated, postulating that environmental factors interact with each other and exacerbate biological vulnerabilities (Afifi, 2007).

Gender differences in some mental disorders has been shown in mental health research (Matud et al., 2022; Sáenz-Herrero, 2019). This is especially important if we look at the most prevalent mental disorders, depressive and anxiety disorders, where a higher prevalence is repeatedly found in women (Sáenz-Herrero, 2019; Santomauro et al., 2021).

According to the European Health Survey 2020, in Spain (Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE], 2020), in population aged 15 and older, depression was more than twice as prevalent in women (9.2%) than in men (4.0%). Furthermore, it is estimated that by 2030 it will be the leading cause of morbidity in women (WHO, 2009). Moreover, research shows that these differences appear to persist across cultures (Van de Velde et al., 2010). Regarding anxiety disorders, the results are similar to those of depressive disorders: 9.1% in women and 4.3% in men (INE, 2020). This high prevalence is also observed if we look at worldwide rates with around 301 million people (4.1%) presenting an anxiety disorder and 280 million people (3.8%) presenting a mood disorder (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), 2023).

Both depressive and anxiety disorders have been denominated emotional disorders (EDs; Bullis et al., 2019), being neuroticism the most important vulnerability factor associated with the etiology, course and maintenance of EDs (Brown & Barlow, 2009). Again, consistent with the data obtained on the prevalence of EDs, in the scientific literature we found that there are higher scores in neuroticism in women (Costa et al., 2001). However, the literature has also shown that women have higher scores in extraversion too, a protective factor against the onset and maintenance of EDs, according to Brown and Barlow's triple vulnerability model (Brown & Barlow, 2009; Schmitt et al., 2008).

In addition to differences in the prevalence of EDs and in neuroticism and extraversion scores, gender differences have been found in specific emotional symptoms and quality of life. For example, different studies suggest that women have a higher lifetime probability of meeting diagnostic criteria for panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and social anxiety disorder, in some cases nearly twice as likely as men (Kinrys & Wygant, 2005; McLean et al., 2011). In addition, these differences are also observed in the clinical symptomatology and in the course and evolution of the disorders (Kinrys & Wygant, 2005; Weissman, 2014). Specifically, some studies have found greater anxiety symptomatology in women compared to men in all age ranges (Leach et al., 2008). Also literature have found a greater interference, low self-esteem, feelings of guilt, negative self-evaluations, psychomotor agitation and rumination in women; while men showed a greater sense of emptiness, difficulty in achieving work and academic objectives, and increased physical, sexual and occupational activity (Londoño-Pérez et al., 2020). Finally, a worse quality of life has also been found in women compared to men (Nolte et al., 2019).

These differences suggest that there may also be differences in other relevant clinical variables such as adherence to treatment and response to psychological treatment for EDs. In this regard, the results of the studies conducted are contradictory, finding studies that show a higher number of dropouts in women (Speck et al., 2008), while others have shown a higher number of dropouts in men (Asher et al., 2019). These results raise the need to explore this issue with a more exhaustive approach, with the aim of designing interventions and strategies to reduce the risk of dropout (Blain et al., 2010).

Regarding treatment response, the literature has not found conclusive results on whether there are gender differences in response to cognitive-behavioral treatment (CBT), finding studies where being female was associated with a more favorable evolution and a greater reduction of symptomatology after a CBT intervention (Asher et al., 2019; Karatzias et al., 2007; Pieh et al., 2012), while others found greater improvement in men after the intervention (Felmingham & Bryant, 2012) or found no statistically significant differences (Cuijpers et al., 2014).

In the specific case of CBT-based transdiagnostic approaches, a single treatment to treat different disorders by focusing on addressing the etiological and maintenance mechanisms shared by a group of disorders (Brown & Barlow, 2009). One of the most well supported transdiagnostic interventions is the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (UP; Barlow et al., 2018). UP emphasizes the presence of emotional regulation deficits in people with EDs observed in their intense emotional responses, aversive reactions to emotions, and avoidance behaviors (Barlow et al., 2018). In addition, its versatility allows its application in group format, which postulates it as an efficient option for public health systems, since it would reduce treatment-related costs (Norton, 2012) and reduce waiting lists (Díaz et al., 2017).

However, althought different systematic reviews and meta-analysis have shown that the UP significantly improves symptoms of anxiety and depression (Carlucci et al., 2021; Cassiello-Robbins et al., 2020; Sakiris & Berle, 2019), and that it is cost-effective when applied in a group format (Peris-Baquero et al., 2022), there are still few studies using the UP that have analyzed whether there are gender differences in the response to treatment. To our knowledge, there are only two studies that have applied the UP and have analyzed gender differences, the studies conducted by Carlucci et al. (2021) and by Varkovitzky et al. (2018). However, none of these studies have analyzed whether there are gender differences in response to treatment when UP is applied in group format, which would have a critical impact on the time needed to recruit participants for the treatment groups and probably in the effectiveness of the intervention.

The aim of our study is to explore whether there are gender differences in treatment retention, number of treatment sessions received and clinical variables, and in the efficacy and response to treatment (UP in group format) of people with a diagnosis of ED who are treated in the Spanish public mental health system. In line with previous literature, our hypotheses are: 1) Women will present higher scores in emotional symptomatology, personality dimensions and interference as well as lower scores in quality of life at the start of treatment; 2) Women will present lower adherence to treatment; 3) The UP will be effective in improving the study outcomes, but there will be differences in score trajectories according to gender.

Method

Participants

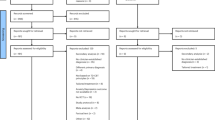

The sample consisted of 277 participants who were part of a multicenter randomized clinical trial (Osma et al., 2018). For this study, only those participants who were assigned to the UP condition in group format were selected, all of them users of the public mental health system and with a primary diagnosis of ED. A total of 78.3% (n = 217) of the participants were female, with a mean age of 41.84 (SD = 11.99, range 18—70), while 21.7% (n = 60) were male, with a mean age of 42.68 (SD = 11.64, range 18—65). The rest of the sociodemographic information can be seen in Table 1, and the flow diagram of the participants throughout the study can be seen in Fig. 1.

Instruments

Primary outcomes

The diagnostic evaluation was carried out through the semi-structured interview ADIS-IV (Di Nardo et al., 1994), for the diagnosis of anxiety and depression disorders according to DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

Sociodemographic information was collected through a questionnaire developed ad hoc, which included data on gender, age, marital status, number of children.

Number of treatment sessions received. This information was collected after the intervention and at each of the follow-up assessments (T2, T3, T4, and T5).

The depressive and anxious symptomatology was evaluated through the Beck depression inventory (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996; Sanz et al., 2003) and Beck anxiety inventory (BAI; Beck & Steer, 1993; Sanz et al., 2012). These instruments consist of 21 items that evaluate the severity of depressive and anxious symptomatology through a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 3, from least to most severe. Both instruments showed adequate internal consistency in the present sample (Cronbach's alpha of 0.91 for BDI-II, and 0.92 for BAI).

Secondary outcomes

Neuroticism and extraversion personality dimensions were assessed through the NEO-FFI (Costa & McCrae, 1999). Specifically, through 12 items for each dimension, with a Likert-type response scale ranging from 0 to 4 from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”. The instrument obtained adequate reliability values in both dimensions (Cronbach's alpha of 0.72 for neuroticism, and 0.81 for extraversion).

Interference was evaluated through the Maladjustment Inventory (MI; Echeburúa et al., 2000). Through 6 items and with a response scale ranging from 0 “Nothing” to 5 “A lot”, it evaluates the interference in the areas of social life, work, free time, couple and family relationships and global interference. A Cronbach's alpha of 0.82 was obtained in the present study.

Quality of life was assessed through the Quality of Life Index (QLI; Ferrans & Powers, 1985; Mezzich et al., 2000). This measure consists of 10 items, with a Likert-type response scale ranging from 0 to 10, from worst to best self-perceived quality of life. The instrument obtained an adequate internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.86.

Procedure

This is a secondary study part of a main study that consisted of a multicenter RCT conducted in public specialized psychological care services comparing the efficacy of UP applied in a group fornat with the treatment as usual (TAU). Both treatment conditions were carried out face-to-face, and the inclusion criteria consisted of: a) Primary diagnosis of emotional disorder (e.g., anxiety disorder, mood disorder, adaptive disorder, among others); b) Over 18 years of age; c) Fully understands the language in which the therapy is performed; d) Can participate in the evaluation and treatment sessions and sign the informed consent; e) In case of pharmacological treatment, maintain it unchanged 3 months prior to the start of treatment and during the treatment.

As for the exclusion criteria: a) The patient has a severe mental disorder (e.g., bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or organic mental disorder), current risk of suicide or substance abuse in the previous 3 months (cannabis, coffee or nicotine consumption is excluded); b) The patient has received in the last 5 years, 8 or more sessions of psychological treatment clearly based on the principles of CBT. In the case of the UP, all groups were led by a therapist and co-therapist, and the intervention consisted of 12 two-hour treatment sessions applied weekly, over approximately 3 months, in groups consisting of approximately 8 to 10 participants. Of the 41 therapists and co-therapists who participated, only 8 were men (19.5%). In any group therapist and co-therapist were men. For this study, only those participants who were assigned to the UP condition in group format were selected. Using G*Power (Faul et al., 2007), statistical power was calculated from our sample size (n = 277), the number of intersubject groups = 2 (Gender), the number of intrasubject measures = 5 (Time) and a medium effect size, obtaining a statistical power of 1. Assessment protocols were conducted face-to-face, in paper and pencil format, at baseline (T1), post-treatment (T2), 3-month follow-up (T3), 6-month follow-up (T4) and 12-month follow-up (T5). All participants signed the informed consent form, and the study was approved by the research ethics committees of the different centers where the participants were recruited. For more information about the characteristics of the study, please see (Osma et al., 2018). Gender-based analysis was carried out following the SAGER (Sex and Gender Equity in Research) guidelines (Heidari et al., 2016).

Data analysis

First, descriptive statistical analyses and mean comparisons were carried out using ANOVA analysis and Chi-square tests. These analyses were carried out with the SPSS software (version 25.0, IBM Corp., 2017). Next, the data were analyzed with linear mixed effects models using the lm4 package (version lme4_1.1 –13; Bates et al., 2015) for R statistical software (version 4.2.1; R Core Team, 2021). Six different models were fitted for each dependent measure: Depression (BDI-II), anxiety (BAI), neuroticism, extraversion, maladjustment (MI) and quality of life (QLI). For each model, Time (T1 = Baseline time, T2 = Post-treatment time, T3 = 3-month follow-up, T4 = 6-month follow-up, T5 = 12-month follow-up), Gender (Men vs. Women) and their interaction term were entered as fixed effects. Time was dummy coded, being T1 the baseline. Gender was also dummy coded, being Men the baseline. Random intercepts for center and participants were included in the random part of the nested models [i.e., Dependent measure ~ Time × Gender + (1|Center/Participant)]. |T|-values > 1.96 were considered to indicate a statistically significant effect.

Results

Socio-demographic results and mean differences in study outcomes by gender at baseline (T1)

The descriptive results for the dependent measures as a function of gender and time are provided in Table 2. No statistically significant differences were found between men and women in age (F = .26, p = .613), primary diagnosis (χ2(12) = 15.09, p = .237), secondary diagnosis (χ2(18) = 10.34, p = .919) and comorbidity (χ2(1) = 1.16, p = .281).

Number of sessions and treatment retention over time as a function of gender

The results showed no statistically significant differences based on gender in the number of treatment sessions attended immediately after treatment (T2) and in the total number of sessions attended at T5. Only differences in T3 (F = 9.08, p = .003, Cohen´s d = 0.58) and T4 (F = 8.00, p = .005, Cohen´s d = 0.56) were found, with men presenting the highest number of sessions attended. Finally, in terms of the treatment retention throughout the study, a total of 38 men (63.3% of treatment retention) and 138 women (63.6% of treatment retention) completed treatment (T2), and a total of 22 men (36.7% of treatment retention) and 81 women (37.3% treatment retention) completed the evaluation protocols up to T5. No statistically significant differences in treatment retention were found between men and women (p > .05).

Evolution of depressive and anxious symptomatology over time as a function of gender

The model for depressive symptomatology showed an R2 coefficient of 0.750. The model also showed significant effects of Time in all the levels (from T2 to T5) (b ranged from -5.86 to -10.29, t ranged from -3.84 to -5.38, all p < .001) and a significant main effect of Gender (b = 4.61, IC95% [0.95;8.27], t = 2.47, p < .05), which points to higher levels of depression for women throughout the period, as can be seen on Table 3 and Fig. 2. In addition, the model showed a significant interaction effect between Gender (women) and Time (T3 and T4) (b = -5.73, IC95% [-9.26;-2.20], t = -3.18, p < .01; and b = -4.65, IC95% [-8.26;-1.05], t = -2.53, p < .05 respectively), pointing to closer levels of depression for women and men only during T3 and T4 evaluations.

Regarding anxious symptomatology, the model showed an R2 coefficient of 0.733. As can be seen on Table 3 and Fig. 2, the model also showed a significant effect of Time in all the levels (from T2 to T5) (b ranged from -7.45 to -9.58, t ranged from -4.59 to -5.57, all p < .001), and a main effect of Gender (b = 4.78, IC95% [1.07;8.48], t = 2.53, p < .05), pointing to higher levels of anxiety for women throughout the period. The model did not show interaction effects between Gender (Women) and Time (T2, T3, T4, T5).

Evolution of neuroticism, extraversion, maladjustment, and quality of life over time as a function of gender

As can be seen on Table 4 and Fig. 3, the model for neuroticism showed an R2 coefficient of 0.642. The model also showed a significant effect of Time in all the levels (from T2 to T5) (b ranged from -2.86 to -5.60, t ranged from -2.65 to -4.21, all p < .01), but did not show a main effect of Gender. Despite of it, the model showed a statistically significant interaction effect between Gender (women) and Time (T4) (b = -2.81, IC95% [-5.36; -0.25], t = -2.16, all p < .05), which points to lower levels of neuroticism for women at T4.

Model estimates for neuroticism and extraversion as a function of Gender (Man vs. Women) and Time (T1 vs. T2 vs. T3 vs. T4 vs. T5). Note: Error bars represent 95% CIs. Dashed line represents a standard deviation above the normative mean for neuroticism, and a standard deviation below the normative mean for extraversion (Manga et al., 2004).

Regarding the model for extraversion, the model showed an R2 coefficient of 0.776. The model also showed a significant effect of Time only in T4 (b = 2.05, IC95% [0.21;3.89], t = 2.18, p < .05). The model did not show a main effect of Gender either. In spite of it, the model also showed a statistically significant interaction effect between Gender (Women) and Time (T3) (b = 2.86, IC95% [0.77;4.95], t = 2.69, p < .01), pointing to statistically significant higher levels of extraversion for women at T3, as can be seen on Table 4 and Fig. 3.

The model for interference, assessed through the MI instrument, showed an R2 coefficient of 0.679. The model also showed a significant effect of Time in all the levels (from T2 to T5) (b ranged from -3.66 to -4.66, t ranged from -3.24 to -4.00, all p < .001), but did not show a main effect of Gender. Despite this, the model showed a significant interaction effect between Gender (Women) and Time (T3 and T4) (b = -3.71, IC95% [-6.25; -1.16], t = -2.85, p < .01; and b = -2.75, IC95% [-5.31;-0.19], t = -2.10, p < .05, respectively), which points to lower levels of MI for women at T3 and T4 evaluation, as can be seen on Table 4 and Fig. 4.

In terms of quality of life, the model showed an R2 coefficient of 0.622. As can be checked on Table 4 and Fig. 4, the model also showed a significant effect of Time in all levels (from T2 to T5) (b ranged from 0.84 to 1.22, t ranged from 3.28 to 4.44, all p < .001), but there were no main or interaction effects due to the Gender of the participants (all t’s < 1.96).

Discussion

This is the first study to explore gender differences in relation to sociodemographic variables, symptoms severity, adherence and response to treatment, and treatment efficacy of a group of individuals with diagnoses of EDs after the application of the UP in group format in public mental health settings in Spain.

Our first hypothesis was that women would present higher scores than men in emotional symptomatology and related clinical variables. The results of this study have partially corroborated this hypothesis. In our study, women had the highest anxiety and depressive scores at baseline, in line with the findings of other studies (Londoño-Pérez et al., 2020; Santomauro et al., 2021) and contrary to others where no differences were found in the variables according to gender (Varkovitzky et al., 2018). However, no differences were found in neuroticism, extraversion, interference or quality of life, contrary to the findings of other studies (Costa et al., 2001; Londoño-Pérez et al., 2020; Nolte et al., 2019).

Our second hypothesis was that women would have lower adherence to treatment, with a higher dropout rate than men. The results of this study have not confirmed this hypothesis. No statistically significant differences were found in the number of sessions at T5, nor in treatment retention, with rates being similar between men and women at all evaluation times. These results of adherence to treatment differ from those obtained by other authors which pointed to a greater dropout of men or women (Asher et al., 2019; Spek et al., 2008), probably because of the difference on the intervention format, transdiagnostic group vs disorder-specific treatment groups, or internet-based treatment.

Our third hypothesis was that the UP would be effective in improving the study outcomes and that there would be differences in response to treatment, with a different score trajectories depending on gender. In general, this hypothesis has been confirmed. Depressive and anxious symptomatology decreases over time regardless of gender, despite the scores for women being higher throughout all the evaluation points. This result coincides with what is shown in the literature (Londoño-Pérez et al., 2020; Santomauro et al., 2021). In addition, once the intervention was received, the scores were equal between the genders, and these results were maintained in the long term (T5). These results are consistent with those reported in the literature (Asher et al., 2019; Carlucci et al., 2021; Felmingham & Bryant, 2012; Pieh et al., 2012; Spek et al., 2008).

Regarding personality dimensions, we found that neuroticism is reduced over time for both men and women and their scores are similar throughout the intervention. This result contrasts with the studies that show that there are higher neuroticism scores in women (Costa et al., 2001), since although there seems to be a tendency for women to score higher in neuroticism, once women receive treatment, their scores are reduced until they reach scores similar to those obtained by men. Based on this result, we can say that the emotion regulation strategies included in the UP were able to reduce neuroticism scores in men and women at post-treatment and over the follow-ups regardless of the baseline scores; thus, it has been confirmed that the UP has been specifically design to target neuroticism (Carlucci et al., 2021), a vulnerability factor related to the etiology and maintenance of EDs (Brown & Barlow, 2009).

A statistically significant improvement on extraversion was only found at T4, with the highest scores corresponding to women. This result would be like the one found in the study of Schmitt et al. (2008). Finally, although no statistically significant changes were observed, there was a clear trend towards improvement, especially if we observe T1 and T5. Although the UP is not originally designed to address extraversion, it does seem to obtain favorable results in its improvement. A possible explanation could be that the different emotional regulation skills that are worked on through the UP also indirectly improve extraversion, serving to improve the appearance and management of pleasant emotions, related, for example, to situations in which the person may have been using maladaptive strategies such as avoidance. Studies such as those conducted by Laposa et al. (2017) and Reinholt et al. (2017) also found changes in extraversion. Another possible explanation for these changes may be associated with applying the intervention in a group format, which would have an impact and a social benefit on the participants (Burlingame et al., 2013).

In relation to interference, the results did not show a main effect of time. However, a different score trajectories according to gender were observed. Specifically, women obtained the lowest scores at T3 and T4. This result contrasts with studies that identify greater interference in women (Londoño-Pérez et al., 2020). Despite this result, when analyzing the scores between men and women at T5, no statistically significant differences were found, so that both women and men saw their interference scores reduced, finally reaching similar scores.

In terms of quality of life, a statistically significant improvement was found over time, a result that coincides with other studies such as that carried out by Wilner et al. (2020). However, the score trajectories were similar between men and women. These results differ from others that point to a worse quality of life for women (Nolte et al., 2019), but coincide with those obtained by Bai et al. (2020) who concluded that the differences in life satisfaction (closely related to quality of life; Garrido et al., 2013) are not significant between men and women.

These results support the efficacy of UP group treatment for the reduction of emotional symptomatology and add to the evidence already available (Carlucci et al., 2021; Cassiello-Robbins et al., 2020; Sakiris & Berle, 2019), and are relevant from a cost-effective point of view. Gender-hetereogeneous UP groups achieve the same clinical results at long-term without adaptations, making it easier to treat a greater number of participants at the same time, thus reducing both the costs associated with treatment (Norton, 2012), and waiting lists in public mental health settings (Díaz et al., 2017).

Limitations

Despite the positive results obtained in this study, it is not without limitations. Firstly, this study was carried out in a specific context, public mental health centers, so the results cannot be generalized to other clinical or community contexts. Despite this limitation, the statistical models we have applied included Center as random effects and the results have not shown statistically significant effects. Another limitation present in this study is that the number of men and women participating was not equal, which may have impacted on the results. Despite this, this distribution is in line with reality, where the highest prevalence of EDs is found in women (WHO, 2017).

Conclusions

The results of this study have shown that the modules and techniques that make up the UP for training in adaptive emotional regulation strategies in people diagnosed with EDs do not require adaptations based on gender, at least in group implementation. Despite the differences in symptomatological severity at the beginning of the treatment, or the differences in the score trajectories of symptoms throughout the treatment, both men and women achieve comparable improvements after the intervention and up to 12 months of follow-up. The improvements obtained include both vulnerability variables (personality dimensions) and emotional symptoms, as well as those related to interference and quality of life. Based on our results, we can recommend the creation of gender-heterogeneous UP groups for the transdiagnostic treatment of people with EDs. These results suggest that the UP applied in group is a cost-effective solution to be chosen in public mental health settings.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Afifi, M. (2007). Gender differences in mental health. Singapore Medical Journal, 48(5), 385–391.

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV). Author.

Asher, M., Hermesh, H., Gur, S., Marom, S., & Aderka, I. (2019). Do men and women arrive, stay, and respond differently to cognitive behavior group therapy for social anxiety disorder? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 64, 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2019.03.005

Aznar, M. P. M., Díaz, F., Ávila, L. A., Rodríguez, M. V., & Aznar, M. J. M. (2003). Diferencias de género en ansiedad y depresión en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios. Psicopatología Clínica Legal y Forense, 3(1), 5–15.

Bai, X., Li, Z., Chen, J., Liu, C., & Wu, X. (2020). Socioeconomic inequalities in mental distress and life satisfaction among older Chinese men and women: The role of family functioning. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(4), 1270–1281. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12960

Barlow, D. H., Farchione, T. J., Sauer-Zavala, S., Latin, H. M., Ellard, K. K., Bullis, J. R., Bentley, K. H., Boettcher, H. T., & Cassiello-Robbins, C. (2018). Unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: Therapist guide. Oxford University Press.

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1993). Beck anxiety inventory manual. Psychological Corporation.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). BDI-II, Beck depression inventory: Manual second edition. Psychological Corporation.

Blain, L. M., Galovski, T. E., & Robinson, T. (2010). Gender differences in recovery from posttraumatic stress disorder: A critical review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(6), 463–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2010.09.001

Brown, T. A., & Barlow, D. H. (2009). A proposal for a dimensional classification system based on the shared features of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: Implications for assessment and treatment. Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 256–271. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016608

Bullis, J. R., Boettcher, H., Sauer-Zavala, S., & Barlow, D. H. (2019). What is an emotional disorder? A transdiagnostic mechanistic definition with implications for assessment, treatment, and prevention. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12278

Burlingame, G. M., Strauss, B., & Joyce, A. (2013). Change mechanisms and effectiveness of small group treatments. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (pp. 640–689). Wiley.

Carlucci, L., Saggino, A., & Balsamo, M. (2021). On the efficacy of the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 87, 101999.

Cassiello-Robbins, C., Southward, M. W., Tirpak, J. W., & Sauer-Zavala, S. (2020). A systematic review of Unified Protocol applications with adult populations: Facilitating widespread dissemination via adaptability. Clinical Psychology Review, 101852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101852

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1999). Revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO five-factor inventory (NEO-FFI) TEA ediciones. Madrid, Spain.

Costa, P. T., Terracciano, A., & McCrae, R. R. (2001). Gender differences in personality traits across cultures: Robust and surprising findings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(2), 322–331. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.2.322

Cuijpers, P., Weitz, E., Twisk, J., Kuehner, C., Cristea, I., David, D.,... & Hollon, S. D. (2014). Gender as predictor and moderator of outcome in cognitive behavior therapy and pharmacotherapy for adult depression: An “individual patient data” meta‐analysis. Depression and Anxiety, 31(11), 941–951. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22328

Di Nardo, P. A., Brown, T. A., & Barlow, D. H. (1994). Anxiety disorders interview schedule for DSM-IV: Lifetime version (ADIS-IV-L). Psychological Corporation.

Díaz, J., Díaz-de-Neira, M., Jarabo, A., Roig, P., & Román, P. (2017). Estudio de derivaciones de Atención Primaria a centros de Salud Mental en pacientes adultos en la Comunidad de Madrid. Clínica y Salud, 28(2), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clysa.2017.03.001

Echeburúa, E., de Corral, P., & Fernández-Montalvo, J. (2000). Escala de Inadaptación: Propiedades psicométricas en contextos clínicos. Análisis y Modificación De Conducta, 26(107), 325–340.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Felmingham, K. L., & Bryant, R. A. (2012). Gender differences in the maintenance of response to cognitive behavior therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(2), 196–200. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027156

Ferrans, C. E., & Powers, M. J. (1985). Quality of life index: Development and psychometric properties. Advances in Nursing Science, 8, 15–24.

Garrido, S., Méndez, I., & Abellán, J.-M. (2013). Analysing the simultaneous relationship between life satisfaction and health-related quality of life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(6), 1813–1838. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9411-x

Heidari, S., Babor, T. F., De Castro, P., Tort, S., & Curno, M. (2016). Sex and Gender Equity in Research: rationale for the SAGER guidelines and recommended use. Research Integrity and Peer Review, 1, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-016-0007-6

IBM Corp. (2017). IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 25.0. IBM Corp.

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). (2023). Global Health Data Exchange (GHDx). Retrieved 03/06/2023, from https://www.healthdata.org/spain?language=149

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). (2020). Encuesta Europea de Salud en España (EESE). Retrieved 03/06/2023, from https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176784&menu=resultados&idp=1254735573175

Karatzias, A., Power, K., McGoldrick, T., Brown, K., Buchanan, R., Sharp, D., & Swanson, V. (2007). Predicting treatment outcome on three measures for post-traumatic stress disorder. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 257(1), 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-006-0682-2

Kinrys, G., & Wygant, L. E. (2005). Anxiety disorders in women: Does gender matter to treatment? Revista Brasileira De Psiquiatria, 27(suppl 2), s43–s50. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-44462005000600003

Laposa, J. M., Mancuso, E., Abraham, G., & Loli-Dano, L. (2017). Unified protocol transdiagnostic treatment in group format: A preliminary investigation with anxious individuals. Behavior Modification, 41(2), 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445516667664

Leach, L. S., Christensen, H., Mackinnon, A. J., Windsor, T. D., & Butterworth, P. (2008). Gender differences in depression and anxiety across the adult lifespan: The role of psychosocial mediators. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(12), 983–998. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0388-z

Londoño-Pérez, C., Cita-Álvarez, A., Niño-León, L., Molano-Cáceres, F., Reyes-Ruíz, C., Vega-Morales, A., & Villa-Campos, C. (2020). Sufrimiento psicológico en hombres y mujeres con síntomas de depresión. Terapia Psicológica, 38(2), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082020000200189

Manga, D., Ramos, F., & Morán, C. (2004). The Spanish norms of the NEO Five-Factor Inventory: New data and analyses for its improvement. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 4(3), 639–648.

Matud, M. P., Zueco, J., Díaz, A., Del Pino, M. J., & Fortes, D. (2022). Gender differences in mental distress and affect balance during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Current Psychology, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03282-w

Mezzich, J. E., Ruipérez, M. A., Pérez, C., Yoon, G., Liu, J., & Mahmud, S. (2000). The Spanish version of the quality of life index: Presentation and validation. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 188(5), 301–305. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-200005000-00008

McLean, C. P., Asnaani, A., Litz, B. T., & Hofmann, S. G. (2011). Gender differences in anxiety disorders: Prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 45(8), 1027–1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006

Nolte, S., Liegl, G., Petersen, M. A., Aaronson, N. K., Costantini, A., Fayers, P. M., Groenvold, M., Holzner, B., Johnson, C. D., Kemmler, G., Tomaszewski, K. A., Waldmann, A., Young, T. E., Rose, M., & EORTC Quality of Life Group (2019). General population normative data for the EORTC QLQ-C30 health-related quality of life questionnaire based on 15,386 persons across 13 European countries, Canada and the Unites States. European Journal of Cancer, 107, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2018.11.024

Norton, P. J. (2012). Group cognitive-behavioral therapy of anxiety: A transdiagnostic treatment manual. Guilford Press.

Osma, J., Suso-Ribera, C., García-Palacios, A., Crespo-Delgado, E., Robert-Flor, C., Sánchez-Guerrero, A., Ferreres-Galan, V., Pérez-Ayerra, L., Malea-Fernández, A., & Torres-Alfosea, M. Á. (2018). Efficacy of the unified protocol for the treatment of emotional disorders in the Spanish public mental health system using a group format: study protocol for a multicenter, randomized, non-inferiority controlled trial. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-018-0866-2

Peris-Baquero, Ó., Moreno, J. D., & Osma, J. (2022). Long-term cost-effectiveness of group unified protocol in the Spanish public mental health system. Current Psychology, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03365-8

Pieh, C., Altmeppen, J., Neumeier, S., Loew, T., Angerer, M., & Lahmann, C. (2012). Geschlechtsunterschiede in der multimodalen Therapie depressiver Störungen mit komorbider Schmerzsymptomatik. Psychiatrische Praxis, 39(06), 280–285. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0032-1305097

R Core Team (2021). R: a language and environment for statistical computing. In R Foundation for Statistical Computing. R foundation for statistical computing Vienna, Austria.

Reinholt, N., Aharoni, R., Winding, C., Rosenberg, N., Rosenbaum, B., & Arnfred, S. (2017). Transdiagnostic group CBT for anxiety disorders: The unified protocol in mental health services. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 46(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2016.1227360

Sáenz-Herrero, M. (2019). Psychopathology in women: Incorporating gender perspective into descriptive psychopathology (2md edn). Springer.

Sakiris, N., & Berle, D. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the Unified Protocol as a transdiagnostic emotion regulation based intervention. Clinical Psychology Review, 72, 101751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101751

Santomauro, D. F., Mantilla Herrera, A. M., Shadid, J., Zheng, P., Ashbaugh, C., Pigott, D. M., Abbafati, C., Adolph, C., Amlag, J. O., Aravkin, A. Y., Bang-Jensen, B. L., Bertolacci, G. J., Bloom, S. S., Castellano, R., Castro, E., Chakrabarti, S., Chattopadhyay, J., Cogen, R. M., Collins, J. K.,… Ferrari, A. J. (2021). Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 398(10312), 1700–1712. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02143-7

Sanz, J., Navarro, M. E., & Vázquez, C. (2003). Adaptación española del Inventario para la Depresión de Beck-II (BDI-II): 1. Propiedades psicométricas en estudiantes universitarios. Análisis y Modificación de Conducta, 29(124), 239–288.

Sanz, J., García-Vera, M. P., & Fortún, M. (2012). The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI): Psychometric properties of the Spanish version in patients with psychological disorders. Behavioral Psychology/ Psicologia Conductual, 20(3), 563–583.

Schmitt, D. P., Realo, A., Voracek, M., & Allik, J. (2008). Why can’t a man be more like a woman? Sex differences in Big Five personality traits across 55 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(1), 168–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.94.1.168

Spek, V., Nyklíček, I., Cuijpers, P., & Pop, V. (2008). Predictors of outcome of group and internet-based cognitive behavior therapy. Journal of Affective Disorders, 105(1–3), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2007.05.001

Van de Velde, S., Bracke, P., & Levecque, K. (2010). Gender differences in depression in 23 European countries. Cross-national variation in the gender gap in depression. Social Science & Medicine, 71(2), 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.035

Varkovitzky, R. L., Sherrill, A. M., & Reger, G. M. (2018). Effectiveness of the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders Among Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Pilot Study. Behavior Modification, 42(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445517724539

Weissman, M. M. (2014). Treatment of Depression: Men and Women Are Different? American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(4), 384–387. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13121668

Wilner, J. G., Dufour, S., Kennedy, K., Sauer-Zavala, S., Boettcher, H., Farchione, T. J., & Barlow, D. H. (2020). Quality of Life in Heterogeneous Anxiety Disorders: Changes Across Cognitive-Behavioral Treatments. Behavior Modification, 44(3), 343–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445518815603

World Health Organization. (2009). Gender and mental health. Retrieved 03/08/2023, from http://www.Who.int/gender/henderandhealth.html

World Health Organization. (2017). Depression and other common mental disorders: Global health estimates. World Health Organization, 1–24. CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants, health professionals and collaborating centers that have made this study possible.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. Support for this study was provided by Plan Estatal de I + D + I 2013–2016 and co-funded by the “ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación y Fomento de la investigación del Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER). Otra manera de hacer Europa” [Grant Number PI17/00320], and Gobierno de Aragón (Departamento de Ciencia, Universidad y Sociedad del Conocimiento)” [Grant Number Research team S31_23R].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Vanessa Ferreres-Galán, Óscar Peris-Baquero and Jorge Osma. Data analysis were performed by Óscar Peris-Baquero and José David Moreno. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Vanessa Ferreres-Galán, Óscar Peris-Baquero and Jorge Osma, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of all collaborating centers.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing interests

The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in any material discussed in this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferreres-Galán, V., Peris-Baquero, Ó., Moreno-Pérez, J.D. et al. Is the Unified Protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders equally effective for men and women?. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06159-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06159-2