Abstract

Recent research has evidenced the importance of height dissatisfaction in male body image, however the impact of height on body image in women remains relatively unexplored. Our study aimed to investigate the association between height, heightdissatisfaction, body dissatisfaction, and eating disorder symptoms in a sample of 139 women from the USA. Participants were recruited using Amazon's MTurk and reported their actual and ideal height, as well as completing measures of height dissatisfaction, and drive for thinness, drive for muscularity, and eating disorder symptoms. A paired sample t-test was utilised to examine differences in participants’ actual and ideal height. Additionally, linear hierarchical multiple regression was used to assess whether height, eating disorder symptoms, drive for thinness, and drive for muscularity uniquely predicted height dissatisfaction, and significant interactions were explored using a simple slope analysis complemented with a Johnson-Neyman analysis. Results showed that 48.92% of women reported identical actual and ideal height, 33.09% of women wanted to be taller, and 13.67% wanted to be shorter than their actual height. Additionally, shorter women tended to report greater height dissatisfaction, and higher levels of drive for thinness and drive for muscularity were associated with increased height dissatisfaction. However, eating disorder symptoms did not uniquely account for significant variance in height dissatisfaction once accounting for drive for thinness and muscularity. Our exploratory analysis also revealed that for taller than average women, height dissatisfaction was more strongly predicted by drive for muscularity, thus implicating the significance of height and muscle dissatisfaction for taller women. Overall, our study demonstrated that height and height dissatisfaction are important components to the theoretical construct of women’s body image, and therefore should be integrated into theoretical models of female body dissatisfaction and considered in assessment, formulation, and treatment of body image-related disorders. Further research with larger and more diverse samples, including clinical populations, is warranted to validate and extend our findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Body dissatisfaction is a pervasive concern across cultures and ages and can manifest in a variety of ways, including concerns about body shape, weight, and size (Grogan, 2021). For women, body image research has historically focused on the desire for thinness (Fitzsimmons-Craft et al., 2012; Prnjak et al., 2020), with more recent research highlighting the importance of muscular size, shape, and tone (Bozsik et al., 2018; Cunningham et al., 2019). Commonly, both women and men internalise ideal and often unattainable bodies comprised of low body fat and notable muscle shape and tone - bodies in line with societal emphasis on thinness and muscularity as most acceptable and attractive (Talbot & Mahlberg, 2022). Idealised bodies are typically challenging for women to obtain and maintain, and body dissatisfaction follows from the perception that one’s body does not adhere to these internalised ideals. Notably, body dissatisfaction has been linked to several negative outcomes such as the development of eating disorders (Rosewall et al., 2018), as well as negative affect and stress (Barnes et al., 2020; Bornioli et al., 2021) and poorer quality of life (Santhira Shagar et al., 2021).

Height is largely unchangeable and cannot be altered through diet or exercise, and as such, may have a unique influence on body image and dissatisfaction. Studies in undergraduate (Talbot & Mahlberg, 2023) and sexual minority men (Griffiths et al., 2017), as well as men recruited from an internet forum for short-statured individuals (O’Gorman et al., 2019) have demonstrated positive associations between height dissatisfaction and muscle dissatisfaction, drive for muscularity, and eating disorder symptoms, and negative associations with quality of life. Actual height has been shown to negatively correlate with height dissatisfaction (Griffiths et al., 2017; O’Gorman et al., 2019; Talbot & Mahlberg, 2023), as well as conformity to masculine norms – a factor that has been heavily implicated in male body dissatisfaction (Gattario et al., 2015). Shorter stature has also been linked to other factors related to body dissatisfaction, such as loneliness (Mo & Bai, 2022) and narcissism (Kozłowska et al., 2023).

Whilst there is emerging research on height dissatisfaction in men, less is known about the impact of height on body image in women. Height, or women’s perception of their height, may impact their body image in a variety of ways. For example, women who are shorter in stature may experience greater dissatisfaction with their bodies, as height is often associated with social desirability and attractiveness (Swami et al., 2008). Indeed, Perkins et al. (2021) found that shorter Australian women were more dissatisfied with their height, felt that they were treated poorly due to their height, and reported poorer quality of life, compared to taller women.

On the other hand, taller women may also experience body dissatisfaction due to a perceived lack of femininity. There is a cultural stereotype that associates femininity with petite or delicate features such as a small frame or delicate bone structure, which may conflict with the typically larger stature of taller women. Taller women may also feel that they fall outside of others’ height preferences, as prior research has established that a dyad consisting of a taller man and shorter woman is the most common preference for heterosexual romantic relationships (Salska et al., 2008; Yancey & Emerson, 2016).

In both cases, dissatisfaction with height may lead to attention towards and behaviours targeting other more changeable dimensions of body image: body fat and muscularity. If one believes that their height, whether too short or too tall, creates a deficit in attractiveness, then they may be driven to engage with compensatory behaviours that reduce their level of body fat and increase their muscle tone or athleticism and thus move closer toward the commonly reported ideal female body (Bozsik et al., 2018; Prnjak et al., 2020). In extreme cases, this could lead to behaviours like food restriction, purging, and compulsive exercise. Indeed, Favaro et al. (2007) demonstrated a link between height and eating disorder psychopathology, finding that shorter stature was associated with an increased risk of having an eating disorder.

It is also reasonable to consider that the relationship between height dissatisfaction and body dissatisfaction may be bidirectional. Women who experience significant body dissatisfaction are rarely focused on a single aspect or dimension of their body, as indicated through studies showing close associations between body fat dissatisfaction, muscle dissatisfaction, and other eating disorder symptoms (Cunningham et al., 2022; Prnjak et al., 2022), and high comorbidity between body dysmorphic disorder - a disorder in which an individual focuses on a perceived deficit in their physical appearance, and eating disorders (Dingemans et al., 2012; Ruffolo et al., 2006). It follows that dissatisfaction with one aspect of one’s body (e.g., body fat or muscularity) may negatively impact their perception of another (e.g., height), or inform a general belief that every aspect of one’s body is unattractive or unacceptable. It is also important to consider the potential perceived impact of height on body proportion. For instance, women wanting to be thinner might see greater height as an avenue to redefining their distribution of body fat or body shape generally. Conversely, greater height might be perceived as an important aspect of achieving strength and power in women with a high drive for muscularity.

Present study

Given the relationship between height dissatisfaction and body dissatisfaction in men and the negative impact of body dissatisfaction on women, we aimed to explore the association between height, height dissatisfaction, and body dissatisfaction-related constructs in women from the USA. Based on previous studies in men we hypothesised that there would be a significant difference between women’s actual height and their desired (ideal) height. Additionally, we hypothesised that women’s height, as well as indices of body dissatisfaction including drive for thinness and muscularity, and eating disorder symptoms, would be significantly associated with height dissatisfaction. Finally, we explored the possibility that a person’s height interacted with the relationship between these predictors, to get a preliminary understanding of whether women of different height are similarly vulnerable to the relationship between height dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms and body dissatisfaction drives.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

Our study utilised data from a larger project aimed at understanding the role of body image and personality traits. The sample for the present study comprised of 139 women from the USA recruited from Amazon’s MTurk. See Table 1 for demographic characteristics of the sample. Informed consent was obtained prior to undertaking the study. Ethics approval for the study was granted by an institutional Human Ethics Research Board at an Australian University (ID: 2021–010 S).

Measures

Participants reported their actual and ideal height and completed the Male Body Attitude Scale-Height subscale (Tylka et al., 2005). We selected this measure as no measure of height dissatisfaction for women exists, and the two items that comprise this scale are non-sex-specific. Of note, this scale has been used to measure height dissatisfaction in women in a previous study (Perkins et al., 2021). Participants endorse their height dissatisfaction on a 6-point scale (1 = never; 6 = always), and items were averaged to create an index of height dissatisfaction with higher scores indicating greater dissatisfaction. To measure drive for thinness we used the Drive for Thinness Scale (Garner & Van Strien, 2004). Participants reported their drive for thinness on a 6-point scale (1 = never; 6 = always), and items were averaged to an create index of drive for thinness with higher scores indicating a greater drive for thinness. Analogously, drive for muscularity was measured with the Drive for Muscularity Scale (McCreary et al., 2004). Items were averaged to create an index of drive for muscularity, with higher scores indicating a greater drive for muscularity.

To measure eating disorder symptoms, we used the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire–Short (Gideon et al., 2016). Participants indicated their frequency of symptoms per week (0 = 0 days; 3 = 6–7 days), and items were averaged to create an index of eating disorder psychopathology with higher scores indicating more eating disorder symptoms.

Statistical analysis

There were six participants with missing data for ideal height. We retained these participants in all analyses. To address our first hypothesis, we utilized a paired sample t-test to examine whether there was a significant difference between participant’s actual and ideal height. To address our second hypothesis, a linear hierarchical multiple regression was used to assess whether height, eating disorder symptoms, drive for thinness, and drive for muscularity uniquely predicted height dissatisfaction. All variables were grand mean centered with gcenter from the EMAtools package to reduce multicollinearity and improve interpretation of the model output. Model assumptions were checked by inspecting the full model using the check_model function from the performance package. Results indicated that assumptions of normality, linearity, and homogeneity of variance of the regression residuals, and multicollinearity of the predictors were all met (see Figure S1 in supplementary materials). In the first step of the hierarchical multiple regression, participants’ height and eating disorder symptom scores were entered as predictors. Drive for thinness scores were entered into the model in the second step, and drive for muscularity scores were entered into the model in the third step. In step four, interaction terms between height and eating disorder symptoms, drive for thinness, and drive for masculinity, respectively, were entered into the model to assess whether height moderated the effects of the predictors on height dissatisfaction.

We entered eating disorders symptoms at step 1 to examine its relationship with height dissatisfaction after controlling for the covariate of actual height. We then entered drive for thinness and drive for muscularity at steps two and three, respectively. The goal for entering these at separate steps was to assess for how each motive contributed to the variance in height dissatisfaction after accounting for eating disorder symptoms. Finally, we entered the interactions with actual height at step 4 - after accounting for the variance in height dissatisfaction already explained by each predictor - to test whether the predictors explanatory power varied at different levels of height. We explored significant interactions using a simple slope analysis complemented with a Johnson-Neyman analysis (Bauer & Curran, 2005) using sim_slopes from the interactions package. The simple slopes analysis involved examining whether the relationship between height dissatisfaction and each drive at higher and lower actual heights (+/- 1 standard deviation of height) was significant. The Johnson-Neyman technique complements this assessment by estimating the threshold(s) of actual height where each relationship becomes significant.

Results

Hypothesis 1: Actual and ideal height in the sample

As seen in Table 1, women on average reported a significantly greater ideal compared to actual height, t(132) = -2.87, p =.005, d = -0.23.

Hypothesis 2: Height dissatisfaction as a function of eating disorder symptoms and body dissatisfaction motives

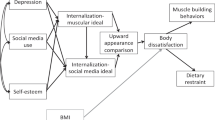

Figure 1 shows the simple correlations between the variables of interest. Notably, height dissatisfaction was moderately correlated with height (r = −.23), and also showed moderate correlations for drive for thinness (r =.30) and muscularity (r =.39), and eating disorder symptoms (r =.34). Table 2 shows the results from a hierarchical regression model assessing the predictive utility of eating disorder symptoms and drive for thinness and muscularity in explaining variance in height dissatisfaction. Step 1 of the model significantly predicted height dissatisfaction, F(2, 136) = 14.65, p <.001, and showed that eating disorder symptoms significantly predicted height dissatisfaction after accounting for variance in height dissatisfaction explained by actual height. The addition of drive for thinness in step 2 statistically improved model fit, F(1,135) = 4.33, p =.04, R2change = 0.02. However, drive for thinness was a non-significant predictor of height dissatisfaction, while eating disorder symptoms remained a unique predictor of height dissatisfaction. Step 3 of the model included the drive for muscularity, which improved model fit, F(1,134) = 8.63, p =.004, R2change = 0.05. The additional predictor significantly explained variance in height dissatisfaction. Importantly, including drive for muscularity rendered eating disorder symptoms a non-significant predictor, which implied drive for muscularity mediated the relationship between eating disorder symptoms and height dissatisfaction. Step 4 of the model explored the possibility that actual height moderated the relationship between each predictor and height dissatisfaction. The addition of the three interaction terms further improved model fit, F(3,131) = 5.77, p <.001, R2change = 0.09. Height significantly interacted with both eating disorder symptoms and drive for muscularity. We explored the suggested moderation patterns below.

Exploratory analyses

As Table 3 illustrates, a simple slopes analysis testing the predictive utility of drive for muscularity at below average (-1 SD), average, and above average height (+ 1 SD) revealed that women with average and above average height demonstrated height dissatisfaction that was significantly explained by a drive for muscularity, whereas women with below average height showed no evidence for this relationship. The Johnson-Neyman analysis further clarified this patterns, as drive for muscularity significantly predicts height dissatisfaction (p <.001) when actual height is 2.73 centimetres or higher above the mean (i.e. taller than ~ 165 cm; see Fig. 2), and this relationship is non-significant below this threshold for of actual height. A similar simple slopes analysis testing the predictive utility of eating disorder symptoms revealed no statistically significant evidence for moderation effects.

Johnson-Neyman plot showing the level range of height (at least 2.73 cm above the mean) where the coefficient for drive for muscularity significantly predicts height dissatisfaction (p <.001). Note: Height is mean centered, so that scores above zero indicate heights greater than the group mean and scores lower than zero indicate heights below the group mean

Discussion

The present study provided one of the first examinations of the relationship between height, height dissatisfaction, body dissatisfaction, and eating disorder symptoms in women. In support of the first hypothesis, women on average wanted to be taller than their actual height. This corresponds to Perkins et al. (2021) study which found analogous results in an Australian community sample of women. Notably, only a third of our sample (33.09%) reported a desire to be taller than their actual height, whilst around half of our sample (48.92%) reported alignment of their actual and ideal height. These results were somewhat lower than expected, given that Perkins et al. (2021) reported that 45% of women in their sample wanted to be taller. These results were also lower than those reported in male samples. For instance, Talbot and Mahlberg (2023) found that 43% of their Australian male sample wished that they were taller.

Results of our regression analyses showed that there was a negative association between height dissatisfaction and reported height, indicating that shorter women tend to report greater height dissatisfaction. The direction of this association aligns with that reported by Perkins et al. (2021) in Australian women, and studies examining height dissatisfaction in men (Griffiths et al., 2017; O’Gorman et al., 2019; Talbot & Mahlberg, 2023); however it is noteworthy that all studies (other than Talbot & Mahlberg, 2023, that reported r = −.21) reported marginally stronger relationships (-0.31 for Perkins et al., 2021, − 0.41 for O’Gorman et al., and − 0.44 for Griffiths et al., 2017) than what we observed in this study. As most prior studies have examined men, this could reflect gender norms whereby one’s height is a more central factor for men with respect to their height dissatisfaction, though this is speculative and needs to be evaluated explicitly in future research.

In support of our second hypothesis, our regression also demonstrated that women’s drive for thinness and muscularity uniquely predicted height dissatisfaction: women who had a high drive for thinness and muscularity, respectively, tended to have greater height dissatisfaction. A potential explanation for this result may lie in the largely unchangeable nature of height. Thus, if women are dissatisfied with a smaller stature, they may seek to enhance other more easily changeable domains of body image such as body fat and muscular shape/tone. In this way, some women may be seeking to compensate for a smaller stature through adapting a drive to be thinner and more toned, and hence more in line with the commonly idealised female body type. Another explanation might lie in how height impacts body proportions. Height itself explained very small amounts of variation in our model compared to eating disorder symptoms and drive for thinness and muscularity, which might suggest that dissatisfaction with height might more closely be driven by how height impacts body proportions. For instance, greater height might function to increase perceptions of thinness or make one’s body look leaner, more toned and athletic – the ‘fit ideal’ female body (Bozsik et al., 2018; McComb & Mills, 2022). Therefore, the desire to be taller might stem from the drive to be perceived as thinner, or more toned/athletic.

Further, although the effect was small, results of our exploratory analysis revealed that for taller than average women, height dissatisfaction was more strongly predicted by drive for muscularity. Essentially, this suggests that amongst taller women, those who want to be taller also want to be more muscular. Simply put, this might reflect a sub-group of our sample who are already tall but generally want to be bigger through both height and muscularity. This novel observation highlights that it is important for researchers and clinicians to consider height dissatisfaction for individuals with body dissatisfaction concerns regardless of their actual height. Prior research has often focused on the vulnerability of shorter people (Favaro et al., 2007; O’Gorman et al., 2019; Perkins et al., 2021) but our data suggests that taller women may also be vulnerable to height dissatisfaction by way of stronger muscularity concerns.

Eating disorder symptoms did not uniquely account for significant variance in height dissatisfaction once drive for thinness and muscularity were entered into our regression model, despite accounting for 31% of the variance in height dissatisfaction in step 1. Therefore, our results support the association between height dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms, yet highlight the important role that body image concerns – specifically, muscularity desires– play in promoting the connection between eating disorder symptoms and height dissatisfaction. Ultimately, our results highlight that body dissatisfaction may underpin women’s height dissatisfaction and its link with eating disorder symptoms. This completements the results of Favaro et al. (2007), which showed a strong link between women with eating disorders and smaller stature, by suggesting that it will be important for future research to consider body dissatisfaction motives when attempting to understand the link between height and eating disorders in future studies.

Limitations and conclusion

Limitations of the present study are noted. First, we utilised self-report measures which may have limited reliability of results (Haeffel & Howard, 2010). Second, our study utilised a W.E.I.R.D sample, thus limiting generalisability of results to non-Western cutlures (Henrich et al., 2010). Third, the validity of collecting data through Amazon Mturk has been called into question for eating disorders-related research (Burnette et al., 2022), thus results should be taken with caution. Last, the cross-sectional design of our study as well as the moderate sample size and our exploratory approch means that generalisability of results is somewhat limited and results should be interpreted with caution.

Despite these limitations, our study provides one of the first examinations of height, height dissatisfaction, body dissatisfaction, and eating disorder symptoms in women. Ultimately, our study adds to the evidence that height and height dissatisfaction are unique significant contributors to women’s body image, and therefore should be integrated into theoretical models of female body dissatisfaction. It also highlights the need to consider height dissatisfaction in assessment. Indeed, no published scale of body dissatisfaction includes a measure of height dissatisfaction beyond the MBAS, which is designed for men and only includes two items to measure height dissatisfaction. A more thorough and validated assessment of height dissatisfaction could be used as part of assessment for women presenting with body image-related disorders, and if relevant, factored into the thus including formulation and treatment of these disorders.

Future studies should aim to replicate our results with larger and more diverse samples of women, and further investigate this relationship in clinical populations such as women with eating disorders. Future studies should also further consider the curvilinear relationships between height, body dissatisfaction, and eating disorder symptoms (i.e., focusing on body dissatisfaction in both taller and shorter women).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Barnes, M., Abhyankar, P., Dimova, E., & Best, C. (2020). Associations between body dissatisfaction and self-reported anxiety and depression in otherwise healthy men: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 15(2), e0229268.

Bauer, D. J., & Curran, P. J. (2005). Probing interactions in fixed and multilevel regression: Inferential and graphical techniques. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 40(3), 373–400.

Bornioli, A., Lewis-Smith, H., Slater, A., & Bray, I. (2021). Body dissatisfaction predicts the onset of depression among adolescent females and males: A prospective study. J Epidemiology Community Health, 75(4), 343–348.

Bozsik, F., Whisenhunt, B. L., Hudson, D. L., Bennett, B., & Lundgren, J. D. (2018). Thin is in? Think again: The rising importance of muscularity in the thin ideal female body. Sex Roles, 79, 609–615.

Burnette, C. B., Luzier, J. L., Bennett, B. L., Weisenmuller, C. M., Kerr, P., Martin, S., Keener, J., & Calderwood, L. (2022). Concerns and recommendations for using Amazon MTurk for eating disorder research. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 55(2), 263–272.

Cunningham, M. L., Szabo, M., Kambanis, P. E., Murray, S. B., Thomas, J. J., Eddy, K. T., Franko, D. L., & Griffiths, S. (2019). Negative psychological correlates of the pursuit of muscularity among women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52(11), 1326–1331.

Cunningham, M. L., Pinkus, R. T., Lavender, J. M., Rodgers, R. F., Mitchison, D., Trompeter, N., Ganson, K. T., Nagata, J. M., Szabo, M., & Murray, S. B. (2022). The ‘not-so-healthy’appearance pursuit? Disentangling unique associations of female drive for toned muscularity with disordered eating and compulsive exercise. Body Image, 42, 276–286.

Dingemans, A. E., van Rood, Y. R., de Groot, I., & van Furth, E. F. (2012). Body dysmorphic disorder in patients with an eating disorder: Prevalence and characteristics. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45(4), 562–569.

Favaro, A., Tenconi, E., Degortes, D., Soave, M., Zanetti, T., Nardi, M. T., Caregaro, L., & Santonastaso, P. (2007). Association between low height and eating disorders: Cause or effect? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40(6), 549–553.

Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E., Harney, M. B., Koehler, L. G., Danzi, L. E., Riddell, M. K., & Bardone-Cone, A. M. (2012). Explaining the relation between thin ideal internalization and body dissatisfaction among college women: The roles of social comparison and body surveillance. Body Image, 9(1), 43–49.

Garner, D. M., & Van Strien, T. (2004). EDI-3. Eating Disorder Inventory-3: Professional Manual.

Gattario, K. H., Frisén, A., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M., Ricciardelli, L. A., Diedrichs, P. C., Yager, Z., Franko, D. L., & Smolak, L. (2015). How is men’s conformity to masculine norms related to their body image? Masculinity and muscularity across western countries. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 16(3), 337.

Gideon, N., Hawkes, N., Mond, J., Saunders, R., Tchanturia, K., & Serpell, L. (2016). Development and psychometric validation of the EDE-QS, a 12 item short form of the eating disorder examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q). PLoS ONE, 11(5), e0152744.

Griffiths, S., Murray, S. B., Medeiros, A., & Blashill, A. J. (2017). The tall and the short of it: An investigation of height ideals, height preferences, height dissatisfaction, heightism, and height-related quality of life impairment among sexual minority men. Body Image, 23, 146–154.

Grogan, S. (2021). Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315681528

Haeffel, G. J., & Howard, G. S. (2010). Self-report: Psychology’s four-letter word. The American Journal of Psychology, 123(2), 181–188.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). Most people are not WEIRD. Nature, 466(7302), 29–29.

Kozłowska, M. A., Talbot, D., & Jonason, P. K. (2023). The Napoleon complex, revisited: Those high on the Dark Triad traits are dissatisfied with their height and are short. Personality and Individual Differences, 203, 111990.

McComb, S. E., & Mills, J. S. (2022). Eating and body image characteristics of those who aspire to the slim-thick, thin, or fit ideal and their impact on state body image. Body Image, 42, 375–384.

McCreary, D. R., Sasse, D. K., Saucier, D. M., & Dorsch, K. D. (2004). Measuring the drive for muscularity: Factorial validity of the drive for muscularity scale in men and women. Psychology of men & Masculinity, 5(1), 49.

Mo, Q. L., & Bai, B. (2022). Height dissatisfaction and loneliness among adolescents: The chain mediating role of social anxiety and social support. Current Psychology, 1–9.

O’Gorman, B., Sheffield, J., & Griffiths, S. (2019). Does masculinity moderate the relationship of height with height dissatisfaction? Findings from an internet forum for short statured men. Body Image, 31, 112–119.

Perkins, T., Hayes, S., & Talbot, D. (2021). Shorter women are more dissatisfied with their height: An exploration of height dissatisfaction in Australian women. Obesities, 1(3), 189–199.

Prnjak, K., Pemberton, S., Helms, E., & Phillips, J. G. (2020). Reactions to ideal body shapes. The Journal of General Psychology, 147(4), 361–380.

Prnjak, K., Fried, E., Mond, J., Hay, P., Bussey, K., Griffiths, S., Trompeter, N., Lonergan, A., & Mitchison, D. (2022). Identifying components of drive for muscularity and leanness associated with core body image disturbance: A network analysis. Psychological Assessment, 34(4), 353.

Rosewall, J. K., Gleaves, D. H., & Latner, J. D. (2018). An examination of risk factors that moderate the body dissatisfaction-eating pathology relationship among New Zealand adolescent girls. Journal of Eating Disorders, 6(1), 1–10.

Ruffolo, J. S., Phillips, K. A., Menard, W., Fay, C., & Weisberg, R. B. (2006). Comorbidity of body dysmorphic disorder and eating disorders: Severity of psychopathology and body image disturbance. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 39(1), 11–19.

Salska, I., Frederick, D. A., Pawlowski, B., Reilly, A. H., Laird, K. T., & Rudd, N. A. (2008). Conditional mate preferences: Factors influencing preferences for height. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(1), 203–215.

Santhira Shagar, P., Donovan, C. L., Boddy, J., Tapp, C., & Harris, N. (2021). Does culture moderate the relationship between body dissatisfaction and quality of life? A comparative study of Australian and Malaysian emerging adults. Health Psychology Open, 8(1), 20551029211018378.

Swami, V., Furnham, A., Balakumar, N., Williams, C., Canaway, K., & Stanistreet, D. (2008). Factors influencing preferences for height: A replication and extension. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(5), 395–400.

Talbot, D., & Mahlberg, J. (2022). Beyond desirable: Preferences for thinness and muscularity are greater than what is rated as desirable by heterosexual Australian undergraduate students. Australian Psychologist, 57(2), 105–116.

Talbot, D., & Mahlberg, J. (2023). Exploration of height dissatisfaction, muscle dissatisfaction, body ideals, and eating disorder symptoms in men. Journal of American College Health, 71(1), 18–23.

Tylka, T. L., Bergeron, D., & Schwartz, J. P. (2005). Development and psychometric evaluation of the male body attitudes scale (MBAS). Body Image, 2(2), 161–175.

Yancey, G., & Emerson, M. O. (2016). Does height matter? An examination of height preferences in romantic coupling. Journal of Family Issues, 37(1), 53–73.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by an Australian University (ID: 2021–010 S).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from every participant included in this study before undertaking the study.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Talbot, D., Mahlberg, J. An examination of the relationship between height, height dissatisfaction, drive for thinness and muscularity, and eating disorder symptoms in north American women. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06108-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06108-z