Abstract

Despite the considerable attention it has received, Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) remains open to criticisms regarding failure to conceptualize the moral domain. MFT was revised in response to these criticisms, along with its measurement tool, the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ-2). However, the validity of this revised theoretical structure and its explanatory power relative to existing alternatives, such as Morality as Cooperation Theory (MAC), has not yet been independently tested. Here we first validated MFT’s revised six-factor structure using the MFQ-2 in a large quasi-representative sample (N = 1099) from a predominantly Muslim country (i.e., Türkiye) and then explored the relationship of these six factors with incentivized measures of moral behavior as well as different psychological variables. Our tests revealed excellent fit values for the six-factor structure proposed by the MFQ-2, which explained more of the variance in criterion variables compared to the MAC Questionnaire (MAC-Q). However, MAC-Q performed better in predicting actual moral behavior (e.g., generosity and cooperation) compared with MFQ-2. Taken together, these findings indicate that, at least for the time being, MFQ-2 and the structure of the moral foundations proposed by MFT can be used to conceptualize the moral domain, but its relatively weak relationship to actual moral behavior limits its insights.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

After centuries of speculation, human morality has become subject to systematic empirical investigation (Darley & Shultz, 1990; Haidt et al., 1993; Kohlberg, 1969; Nichols, 2002; Piaget, 1965; Shweder et al., 2013). These scientific debates led to the emergence of Haidt and Graham’s Moral Foundations Theory (MFT; Haidt & Graham, 2007) as the main framework for conceptualizing the domain of human moral psychology and behavior. MFT proposes that morality is based on a specific set of evolved intuitions and, in contrast to previous accounts of morality, posits that these intuitions shape moral judgment. Accordingly, there are five different (intuitive and automatic) moral foundations as follows: care/harm, fairness/reciprocity, ingroup/loyalty, authority/respect, purity/sanctity.

The care/harm foundation denotes prosocial behavior toward vulnerable group members who require care or protection. The fairness/reciprocity foundation refers to the moral sensitivity necessary to maintain intragroup justice and order. Ingroup/loyalty foundation refers to loyalty to one’s own group, as maintaining group unity is of vital importance in competition with other groups. Obedience to authority is another foundation important for cohesion and order in group hierarchies. Lastly, the moral foundation of purity/sanctity is defined as moral sensitivity that is believed to have evolved due to disgust sensitivity. This adaptation, which protects group members from diseases by motivating various preventive health behaviors (e.g., personal hygiene or avoidance of those who are sick), also affects moral judgments about purity. Graham et al. (2009) defined the care/harm and fairness/reciprocity foundations as “individualizing” principles and the other three foundations as “binding” principles related to group affiliation. Accumulated evidence mostly from WEIRD samples indicated that while politically liberal individuals consider only the individualizing dimensions as moral, politically conservative individuals give relatively equal importance to all five dimensions (Graham et al., 2011). Studies consistently underscore the predictive capacity of moral foundations in anticipating diverse outcomes, encompassing responses to sacrificial dilemmas (Crone & Laham, 2015), empathic concerns (Dawson et al., 2021; Strupp-Levitsky et al., 2020), voting behavior (Franks & Scherr, 2015; Iyer et al., 2010), support for stem cell research (Clifford & Jerit, 2013), war attitudes (Koleva et al., 2012), and behavioral compliance during the Covid-19 pandemic (Chan, 2021). The MFT framework has been extensively applied to environmental issues, revealing a consistent association between the endorsement of care and fairness foundations and the willingness to take action on climate change (Dawson & Tyson, 2012; Dickinson et al., 2016), self-reported adherence to pro-environmental norms regarding climate change (Jansson & Dorrepaal, 2015), and self-reported engagement in climate-friendly consumption (Vainio & Makiniemi, 2016; Welsch, 2020). Additionally, investigations into the association between moral foundations and prosocial intentions and behaviors have yielded insightful findings. Individuals emphasizing individualizing foundations over binding foundations tend to exhibit higher prosocial intentions in the presence of strong need (Süssenbach et al., 2019) and report increased donations to international aid and outgroup members (Nilsson et al., 2020). Conversely, those endorsing binding foundations show a diminished likelihood to allocate money in trust games (Clark et al., 2017).

Numerous empirical studies supported the validity of the MFQ-1 (e.g., Doğruyol et al., 2019; Du, 2019). However, several studies have unearthed various limitations for MFT (e.g., Nilsson & Erlandsson, 2015; Yilmaz & Saribay, 2018; Zakharin & Bates, 2021). One major concern pertains to the statistical fit values of the primary measurement tool for the five moral dimensions proposed by MFT, the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ), which often fall below widely accepted benchmarks. Graham et al. (2011) conducted a cross-cultural confirmatory factor analysis of the MFQ, revealing that the five-factor model outperformed alternative models such as individualizing/binding two-factor model and the three-factor model proposed by Shweder et al. (2013), which consists of autonomy (care and fairness), community (loyalty and authority), and divinity (sanctity). While this finding was replicated in various cultures, many studies reported fit values that did not meet standard criteria (e.g., CFI < 0.90). For example, Davies et al. (2014) conducted a comprehensive validation study of the MFQ with a large sample size in New Zealand (N = 3,994), finding that the 5-factor model demonstrated superior fit compared to alternative structural solutions such as the single-factor, two-factor, and hierarchical models. Similarly, Du (2019) conducted a validation study of the MFQ in China, concluding that the five-factor model exhibited superior fit relative to alternative configurations with fewer factors. Nevertheless, other studies reported that the five-factor solutions failed to converge and lacked requisite fit adequacy. Iurino and Saucier (2018) examined the 5-factor structure across 27 countries with 8,055 participants, revealing fit indices falling below established thresholds. Consistent findings were observed in investigations across various national contexts, including Holland (De Buck & Pauwels, 2023), Sweden (Nilsson & Erlandsson, 2015), the United Kingdom (Zakharin & Bates, 2021), and non-WEIRD countries like Hungary (Hadarics & Kende, 2017) and Türkiye (Yalçındağ et al., 2017; Yilmaz et al., 2016a). Conversely, some studies argue for models deviating from the quintessential 5-factor structure. In Australia (Smith et al., 2017) and Brazil (Moreira et al., 2019), a 2-factor model, distinguishing individualizing versus binding factors, demonstrated superior fit compared to the canonical 5-factor model. Harper and Rhodes (2021) proposed a three-factor model (traditionalism, compassion, and liberty) as more effective than other options. Even though Zakharin and Bates (2021) found the five-factor model to be better than other solutions despite its low fit indices, in a subsequent study, they identified the multi-trait multi-method as the optimal solution among the two-factor, five-factor, and hierarchical models. They also introduced two additional foundations: one pertaining to loyalty, distinguishing between loyalty to country and loyalty to clan, and another related to purity, encompassing purity and sanctity. This results in a total of seven foundations overall. Thus, while some studies highlight the predictive capacity of moral foundations measured by the MFQ, a substantial body of research has scrutinized the reliability and validity of the questionnaire, often encountering challenges in achieving satisfactory fit indices and maintaining a consistent factor structure.

The Theory of Morality as Cooperation (MAC) is a recent theoretical framework that challenges MFT by proposing an alternative conceptualization of the moral domain (Curry, 2016). MAC posits that morality has evolved to facilitate cooperation. Accordingly, the moral domain consists of seven different foundations as follows: family values, loyalty to the group, reciprocity, heroism, deference, fairness, and property (Curry et al., 2019). The family dimension helps resolve problems of resource distribution among relatives and is associated with characteristics such as caring for offspring and helping relatives. Loyalty to the group is a dimension that promotes harmonious cooperation for mutual benefit and is associated with features such as forming coalitions, favoring one’s own group, and adopting local traditions. Reciprocity is a dimension that helps regulate social exchange and is directly related to moral virtues that determine interpersonal relationships, such as eliminating free-riding, trust, and patience. Heroism and obedience relate to two different moral foundations that become relevant, especially in situations of conflict, and they correspond to aggressive and avoidant behavior, respectively. Fairness is another dimension that regulates the sharing of resources and is associated with characteristics such as a sense of equality and fair distribution. The last dimension, property, relates to issues of ownership. In summary, according to MAC, loyalty to group leaders, cooperation (especially for group defense), trustworthiness in identifying and punishing norm violations, showing courage or obedience for group protection, and respecting property are universally accepted moral mechanisms (Curry et al., 2019).

More specifically, MAC argues that morality is an evolved response to resolve problems related to cooperation. Therefore, it does not include dimensions such as the “care” or “sanctity” previously defined as moral foundations by MFT, with the argument that these dimensions are not directly related to cooperation and that care is already inherent in some domains, such as family values and group loyalty. Curry et al. (2019) conducted a survey to validate the Morality as Cooperation Questionnaire (MAC-Q) using Western online samples and demonstrated that it has better fit values than the MFQ. Similarly, in an independent standardization study, Yilmaz et al. (2021) showed that the MAC-Q had good fit values in Türkiye and performed significantly better than the MFQ in predicting outcome variables such as prosocial intentions and political ideology. Overall, the MAC distinguishes itself from the MFT in terms of both its theoretical underpinnings and the fit values associated with the measurement tool used to assess the morality.

Motivated by these criticisms and related studies, Atari et al. (2023) developed MFQ-2 and redesigned all scale items. Specifically, MFQ is criticized for treating equality and proportionality as identical concepts, despite their theoretical differences. The argument posits individuals may assign significance to proportionality even when they do not place the same level of importance on equality, or vice versa. This variation is attributed to several factors, such as social and cultural influences. The contention is that in Western culture, equality and proportionality are closely intertwined. So, they distinguished between fairness, breaking it down into two different foundations as equality and proportionality acknowledging that the notion of cultural connection may not apply universally. One of the significant modifications introduced in MFQ-2 pertains to the item formats within the questionnaire. In MFQ-1, two distinct item formats, namely “judgment” and “relevance,” were employed. For judgment items, participants were asked to indicate their agreement level with various moral judgments (e.g., “Justice is the most important requirement for a society”). On the other hand, for relevance items, participants were asked to express the degree to which they found specific defined actions relevant when making decisions about what is right or wrong (e.g., “Whether or not someone acted unfairly”). In the development of MFQ-2, Atari et al. (2023) opted to use the judgment format. Their rationale was based on the proposition that including a relevance section had been shown to reduce internal consistencies and produced confusion during usage of measurement.

Based on three online studies conducted in 25 different cultures, equality, and proportionality emerged as separate factors, and the six-factor structure showed a good fit to the data overall. In the current form of the MFT, in addition to care, loyalty, authority, and sanctity, equality is defined as the belief that people should endorse and enforce equal social relations, whereas proportionality is defined as the belief that people should value merit-based systems where rewards are proportional to contributions. Likewise, significant variations were observed depending on culture and context. In addition to the original study by Atari et al. (2023), an independent evaluation of the MFQ-2 was conducted on participants from the U.K. and U.S. by Zakharin and Bates (2023). This investigation confirmed the validity of the six-factor model proposed by MFQ-2, with an interesting distinction observed in the Loyalty foundation. Specifically, Loyalty was better represented as a two-factor construct, encompassing Loyalty to country and Loyalty to clan, aligning with findings from their 2021 study. Zakharin and Bates (2023) also highlighted the necessity of both individualizing and binding foundations for a good fit. However, they acknowledged a potential limitation, recognizing that these distinctions between hierarchical factors might be specific to WEIRD cultures, consistent with the proposal by Atari et al. (2023). Hence, an essential next step involves conducting an independent test of MFQ-2 in non-WEIRD cultures to examine whether MFT effectively explains moral domains across diverse cultural contexts. To date, no such independent replication of MFQ-2 has been conducted in non-WEIRD cultures.

Both Atari et al. (2023) and Zakharin and Bates (2023) used several different scales to show external validity such as Schwartz Values Survey (Schwartz, 1992), Moral Foundations Questionnaire-1 (Graham et al., 2011) and Belief in a Just World (Dalbert, 1999). However, none of the existing studies have explored the relationship between the endorsement of moral foundations, as measured by MFQ-2, and actual moral behavior. Instead, these studies have predominantly focused on intentions, despite the well-documented intention-behavior gap in the literature. A notable example is the meta-analysis conducted by Webb and Sheeran (2006), which revealed that manipulating intentions, while predicting a medium-to-large effect size, only resulted in a small-to-medium effect on behavior change. Consequently, there is a need for a study that empirically demonstrates the capacity of MFQ-2 to predict real moral behavior.

In summary, despite the widespread utilization of the Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ) and supporting studies for its original 5-factor model structure, these investigations often fail to meet adequate fit indices (Davies et al., 2014; Graham et al., 2011; Iurino & Saucier, 2018; Nilsson & Erlandsson, 2015), falling below the established threshold. Notably, certain studies propose alternative factor solutions, such as a 2-factor model (Moreira et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2017) and a 3-factor model (Harper & Rhodes, 2021). Addressing the inconsistencies and limitations in the existing literature, Atari et al. (2023) developed MFQ-2, adopting a six-factor structure and testing it across 25 diverse cultures. However, the MFQ-2 lacks independent validation and remains untested in non-WEIRD countries like Türkiye. Furthermore, the association between moral foundations, as measured by the six-factor model, and actual moral behavior remains unclear. Conversely, another recent theoretical framework, the MAC, offers an alternative conceptualization of morality, incorporating seven moral dimensions. While the MAC-Q demonstrated favorable fit indices in Türkiye, it also outperformed the MFQ in predicting prosocial intentions (Yilmaz et al., 2021). In the present study, our objectives were threefold: (1) to assess the validity of the MFQ-2 on a sample representative of the Turkish population in terms of age and gender and (2) to investigate the relationship between MFQ-2 scores and moral behavior, specifically predicting generosity and cooperation behavior, and (3) to compare exploratory power of the MFQ-2 and MAC-Q in predicting criterion variables. Building upon the established predictive roles of the MFQ and MAC-Q in prosocial intentions (Yilmaz et al., 2021), we anticipated a correlation between MFQ-2 scores and prosocial behavior.

The present research

MFT is committed to explaining the moral domain across all cultures, but Atari et al.‘s dataset (2023) misses some important cultural contexts. In particular, it is not clear whether MFQ-2 extends to non-WEIRD cultures such as Türkiye where the majority of the population is predominantly Muslim. Likewise, the relationship between MFQ-2 and actual moral behavior has not yet been tested. Therefore, in this preregistered study, we first tested the validity of MFQ-2 on a sample representative of the Turkish population in terms of age and gender and examined whether MFQ-2 predicts generosity and cooperation behavior.

Method

The preregistration form, the data, and the analysis codes are available at the Open Science Framework (OSF): https://osf.io/x62vp/?view_only=d0756ec739e94be895081b7ebc460871.

Participants

Initially, 1892 participants were recruited for our online study via a local survey data collection agency (Istanbul Economics Research; https://researchistanbul.com/home/). A target sample size of 1,500 was determined before data collection. Initially, given the constraints of our limited resources for this study, we made the decision to maximize participant recruitment, resulting in a total of 1500 participants. While a priori power analysis is a widely employed technique for determining sample size, alternative methods may be considered for making informed decisions regarding sample size in the presence of resource limitations (Lakens, 2022). Considering potential attrition and without any data analysis, we oversampled, ending with 1892 participants. As preregistered, those who failed to provide complete answers to MFQ-2 (n = 675) and those who were identified as multivariate outliers on the 36 items of the MFQ-2 scale as exhibiting in Mahalanobis distance (n = 118, χ2 (36) = 67.99, p < .001) were excluded from the analyses. The final sample size was 1099 (Mage = 33.22, SD = 16.17; 578 female). Post hoc, we ran both sensitivity and achieved power analysis. The standard sensitivity analysis for a Pearson correlation test with α = 0.05, 1 - β = 0.90, and N = 1099 revealed that our design could reliably detect magnitudes greater than r = .10. The achieved power analysis (Moshagen & Erdfelder, 2016) with RMSEA = 0.05 as the level of misspecification on MFQ-2 items revealed that 1099 observations achieved power higher than > 99.9%.

Procedure

The study design was correlational. The study design was correlational. The translation of the MFQ-2 scale into Turkish involved an independent translation process conducted by two authors. The translated version underwent review by two additional authors to ensure consensus and accuracy. Subsequently, the materials were uploaded onto the Qualtrics platform, and the online participation link, facilitating access for participants to complete the questionnaire, was shared with them. All participants received the same instructions. The scales and questionnaires were randomly presented, followed by a standard demographic form. We used lotteries to motivate participation and task compliance. As noted in the instructions, fifty participants were randomly chosen after the end of the study to receive 50 Turkish lira for their participation. Two additional lottery tickets were randomly distributed, each providing an endowment of 100 Turkish lira to be used in a randomly selected economic game. For these two participants and their partners in the game, the outcome of the economic game was actually implemented. This is a valid and cost-saving incentivization technique, previously used in the literature (e.g., Charness et al., 2016). Before initiating the data analysis, a data cleaning procedure was executed in accordance with the preregistered criteria described above. Initially, confirmatory analyses were performed to evaluate the construct validity of MFQ-2, followed by exploratory analyses.

Materials

Moral Foundations Questionnaire-2 (MFQ-2)

This version builds on the first version of the scale introduced by Graham et al. (2009, 2011) and created by Atari et al. (2023). The MFQ-2 subscales include Care, Equality, Proportionality, Loyalty, Authority, and Purity. Participants rate their agreement with each item on a five-point Likert scale that 1 indicates “Does not define me at all” while 5 indicates “Does define me at all”. The MFQ-2 demonstrates high internal consistency, with reliability coefficients that range from 0.82 to 0.89 across the subscales. There are 35 items in the questionnaire such as “Caring for people who are suffering is an important virtue”, “Everyone should defend their country when necessary”.

Morality as Cooperation-Questionnaire (MAC-Q)

Grounded in the Morality as Cooperation Theory (Curry, 2016), Morality as Cooperation-Questionnaire (Curry et al., 2019) comprises seven subscales: family, group, reciprocity, heroism, fairness, deference, and property. Yilmaz et al. (2021) adapted the scale into Turkish, and the relevance (vs. judgment) subscale showed acceptable levels of internal consistency reliability, ranging from 0.69 to 0.89. Following Yilmaz et al. (2021), we used only relevance subscale of MAC-Q. Reliability coefficients of MAC-Q ranged from 0.81 to 0.89 across the subscales. Participants are asked to indicate the extent of importance they assign to several situations on a scale of 0 to 100 when making decisions. There are 22 items describing various situations, such as " People should be willing to do anything to help a member of their family” or " Society should do more to honour its heroes.”

Public goods game

Each participant is given an equal amount of money at the beginning of the game. They can decide to keep some for themselves or contribute any amount to a public pool. The money donated to the public pool is then multiplied by two and distributed equally among all participants. The amount of money contributed is used to measure cooperative behavior. Derived from experimental economics, Public Goods Game (PGG) is widely used in behavioral sciences as a tool to predict cooperative behavior. Several studies have demonstrated its predictive validity (Englmaier & Gebhardt, 2011; Fehr & Leibbrandt, 2008; Hilbig et al., 2012).

Dictator game

The dictator game is a standard measure of generosity by determining how much of the money the active participant, the dictator, shares with the passive participant. The amount of money shared with the other participant is considered a measure of generosity. Similar to the PGG, the Dictator Game (DG) is an economic game extensively employed in behavioral sciences literature to predict generosity. Its predictive validity has been demonstrated in various studies, including those conducted by Barr and Zeitlin (2010), Stoop (2013), and Barends et al. (2019).

Uncertainty avoidance

Sariçam (2014) translated the twelve-item scale by Carleton et al. (2007) into Turkish. It measures participants’ predisposition to respond negatively to perceived uncertainty (Carleton et al., 2007; Shane, 1995). The scale has good internal consistency with a reliability level of 0.91. Participants indicated their agreement on 1 (does not define me at all) to 5 (does define me at all) Likert-type scale. “A small unforeseen event can spoil everything, even with the best of planning”, “I always want to know what the future has in store for me” are the example items from the scale.

Belief in zero-sum game

One’s tendency to interpret a situation as either a win or a loss is referred to as belief in a zero-sum game. Participants’ belief in a zero-sum game was assessed using this eight-item scale created by Różycka-Tran et al. (2015) for exploratory purposes. In a cross-cultural study conducted in 36 countries, Różycka-Tran et al. (2019) found that the scale reliability ranges between 0.69 and 0.95. The scale has good internal consistency with a reliability level of 0.87. The seven-point-Likert-type scale was used that 1 indicates “totally not agree” and 7 indicates “totally agree”. The example from the scale is as follows: “The well-being of a minority is achieved at the expense of harm to the majority”.

Reflective thinking

The Turkish versions of the Cognitive Reflection Test (Frederick, 2005) and the Cognitive Reflection Test 2 (Thomson & Oppenheimer, 2016) were employed to measure the reflective thinking tendency of participants. These tests have a single correct answer, which can be attained through reflective thinking. The CRT total score is calculated based on the average of CRT-1 and CRT-2 scores with a reliability level of 0.69.

Demographic form

Participants were asked to provide the following information: age, gender, education, socioeconomic status, and location of residence. In addition, they were asked to indicate their trust in other players in the economic games they played for exploratory purposes.

Data analysis

As detailed in the introduction, numerous studies have presented varying models with different numbers of factors. In this study, we similarly explored and tested different models, considering insights from the findings of previous research. For example, a six-factor model was examined, as Atari et al. (2023) showed that it is the best-fitting model in certain cultural contexts. Additionally, a single-factor model was tested, inspired by Atari et al.’s (2023) demonstration that the six moral foundations revealed single higher-order dimension in sixteen samples out of twenty. In the remaining four samples, they established the individualizing-binding distinction. Atari et al. (2023) indicated that individualizing-binding distinction might be more applicable to WEIRD cultures. Consequently, to explore whether individualizing-binding distinction is applicable to our sample and the role of recently added proportionality dimension on individualizing-binding distinction, we tested various alternatives; with one specifying that the proportionality foundation predicted individualizing foundations and the other predicting binding foundations, and a third alternative with five foundations proposed by the MFQ-1 (by omitting proportionality foundation). We tested each model using single-order and higher-order solutions to further explore the factor structure.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Exploratory Structural Equation Modelling (ESEM) were conducted in Mplus (Ver. 8) (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). As confirmatory analyses, we first conducted ESEM separately on the MFQ-2 and MAC-Q items. We then ran a series of models to explore how the six moral foundations of MFQ-2 map onto previous higher-order conceptualization (i.e., individualizing and binding). First, we ran a first-order single-factor CFA model and a second-order single-factor ESEM model to test whether the six-factor structure of the moral foundations of MFQ-2 predict a higher-order moral latent construct. Then, three alternative first-order ESEMs based on the previous conceptualization of original MFQ were conducted, where care and fairness items represent individualizing and loyalty, authority, and purity items represent binding foundations. In two of these models, proportionality either predicted individualizing or binding, whereas, in the third model, proportionality was excluded from the model to test the original conceptualization in MFQ-1. Afterward, we estimated these three alternative models hierarchically as second-order models. In all second-order models, the ESEM-within-CFA strategy was used (Morin & Asparouhov, 2018). Accordingly, first-order ESEM models were respecified within CFA models by setting unstandardized factor loadings as starting values and freely estimating factor variances. Finally, following Van Zyl and Ten Klooster’s (2022) suggestions, we ran CFA counterparts of ESEM models to determine the best-fitting model.

In ESEM specifications, items were forced to load on a targeted factor, and cross-loadings on non-targeted factors were estimated but aimed to be as close to zero as possible. Given its ability to model categorical data (Brown, 2006), we used weighted least squares (WLSMV) on MFQ-2 items and maximum likelihood (ML) on the ordered (non-categorical) MAC-Q items. Target rotation was used in all models assuming correlated latent structures. Nested models were compared using delta fit indices. Changes in RMSEA larger than 0.015 and changes in TLI larger than 0.01 indicate improved fit (Chen, 2007).

Results

Construct validity

Results of ESEM with the 36 items of MFQ-2 revealed excellent fit to the data (χ2 = 847.32, df = 429, p < .001; CFI = 0.990; TLI = 0.985; RMSEA = 0.030, 90% CI [0.027, 0.033]) and outperformed its CFA equivalent (ΔRMSEA = 0.043, ΔTLI = 0.072). All items were significantly loaded on targeted factors (Table 1).

Five items (three items of authority, one item of equality, and one item of loyalty) cross-loaded on non-targeted factors with larger loadings than the targeted loadings. Considering ESEM and high latent intercorrelations between moral foundations, we decided to retain cross-loaded items. We then tested the factor structure of MAC-Q to compare the construct validity of MFQ-2 and MAC. The seven-factor model yielded excellent fit to the data (χ2 = 135.91, df = 84, p < .001; CFI = 0.997; TLI = 0.992; RMSEA = 0.026, 90% CI [0.017, 0.034]). As a result, both the six-factor structure of MFQ-2 and the seven-factor structure of MAC-Q were validated.Footnote 1

Across exploratory models, a single-factor model where all items loaded on a single latent construct revealed a poor fit to the data. The remaining models showed good-to-excellent fit to the data (Table 2). Second-order ESEM-within-CFA models yielded better fit compared to first-order ESEM, first-order CFA, and second-order CFA counterparts. However, the model fit values of the ESEM-within-CFA models were comparable across three alternative specifications of individualizing and binding foundations. Morin et al. (2020) argued that latent correlations should also be considered in ESEM models to evaluate model fit. Latent correlations were relatively high (r’s ranged between 0.87 and 1.30), suggesting linear dependency among latent constructs. Since high intercorrelations are indicative of model misspecification (i.e., level of distinction between latent constructs) and since second-order single-factor models provided more parsimonious solutions with comparable fit indices, we retained the second-order single-factor model (ESEM-within-CFA) as the best fitting model Footnote 2. Thus, we calculated a total score for MFQ-2.

Explanatory power

We estimated correlations of MFQ-2, behavioral (e.g., incentivized) measures of cooperation and generosity (i.e., public goods game and dictator game), analytic cognitive style (i.e., CRT-1 and CRT-2), demographic variables (i.e., religiosity and political ideology), and other criterion variables (i.e., uncertainty avoidance and zero-sum beliefs) along with seven MAC-Q dimensions. Descriptive statistics and gender differences for MFQ-2, MAC-Q, and criterion variables are presented in Table 3.

The total score of MFQ-2 was positively, albeit weakly, correlated with the amount of money allocation in the Public Goods Game (r = .062, p = .040), religiosity (r = .270, p < .001), and right-wing political ideology (r = .186, p < .001), while it was negatively, albeit weakly, correlated with CRT total score (r = −.091, p = .003). Besides, the total score of MAC-Q was positively correlated with the amount of money allocation in the Public Goods Game (r = .217, p < .001) and Dictator game (r = .150, p < .001), religiosity (r = .081, p = .022), and CRT total score (r = .100, p = .002).

More specifically, care was positively correlated with the amount of money allocated in the Public Goods Game (r = .083, p = .006) and the Dictator Game (r = 070, p = .020). Besides, proportionality (r = .087, p = .004) and loyalty (r = .065, p = .031) were also positively associated with the amount of money allocated in the Public Goods Game. All six dimensions were positively correlated with religiosity (ranged between 0.13 and 0.38, p’s < 0.001) except proportionality. Care (r = .104, p = .003), loyalty (r = .157, p < .001), authority (r = .274, p < .001), and purity (r = .284, p < .001) were correlated with right-wing political ideology. Among the correlations between moral foundations and analytic cognitive style, five moral foundations that were represented in the previous formulation of MFQ were negatively associated with at least one of the CRT scores (significant correlations ranged between − 0.08 and − 0.17) while recently added proportionality foundation was positively associated with CRT-2 (r = .11, p = .001). Results also showed significant associations between all moral foundations and other variables, such as uncertainty avoidance and zero-sum beliefs (ranged between 0.26 and 0.44, p’s < 0.001). A summary of the correlations is presented in Table 1S.

We used MFQ-2 scores in predicting criterion variables to test the unique predictive power of each moral foundation. We also predicted the same criterion variables using MAC-Q dimensions to compare the exploratory power of the two scales. Thus, we regressed eight criterion variables on MFQ-2 and MAC-Q scores separately (Table 4). Results of regression analyses using MFQ-2 scores as predictors revealed that equality predicted higher levels of cooperative behavior, B = -2.73, p = .040; 95% CI [-5.33, -0.12], F(6, 1092) = 2.41, p = .026.Footnote 3 Care was the only predictor of generosity (i.e., the monetary amount allocated to the other player in the Dictator Game); however, the regression model was not significant, B = 5.33, p = .006; 95% CI [1.50, 9.17], F(6, 1092) = 1.55, p = .158.

Equality (Breligiosity = -0.16, p = .025; 95% CI [-0.30, -0.02], Bideology = -0.17, p = .010; 95% CI [-0.30, -0.04]) and Proportionality (Breligiosity = -0.60, p < .001; 95% CI [-0.82, -0.39], Bideology = -0.22, p = .031; 95% CI [-0.41, -0.02]) predicted lower levels of religiosity and right-wing political ideologyFootnote 4. On the contrary, authority (Breligiosity = 0.70, p < .001; 95% CI [0.47, 0.92], Bideology = 0.50, p < .001; 95% CI [0.29, 0.71]) and purity (Breligiosity = 0.57, p < .001; 95% CI [0.37, 0.78], Bideology = 0.47, p < .001; 95% CI [0.28, 0.66] predicted higher levels of religiosity, F(6, 799) = 37.88, p < .001, and right-wing political ideology, F(6, 799) = 19.88, p < .001.

In predicting analytic cognitive style, equality (BCRT−1 = -0.16, p = .025; 95% CI [-0.30, -0.02], BCRT−2 = -0.17, p = .010; 95% CI [-0.30, -0.04]) and authority (BCRT−1 = -0.16, p = .025; 95% CI [-0.30, -0.02], BCRT−2 = -0.17, p = .010; 95% CI [-0.30, -0.04]) negatively predicted CRT-1 (F(6, 799) = 19.88, p < .001) and CRT-2 (F(6, 799) = 19.88, p < .001). On the other hand, proportionality (BCRT−1 = 0.70, p < .001; 95% CI [0.47, 0.92], BCRT−2 = 0.50, p < .001; 95% CI [0.29, 0.71]) predicted improved analytic thinking performance on CRT scores. Finally, equality and proportionality were associated with higher levels of uncertainty avoidance and zero-sum beliefs. On average, MFQ-2 scores explained 12% of the variance in criterion variables whereas MAC-Q scores explained 5% of the variance on average. The MFQ-2 explained more variance in the criterion variables than MAC. However, when we look at the magnitudes of the relationship between MFQ-2, MAC-Q, and moral behaviors, MAC-Q (r’s ranging from 0.11 to 0.22) performed better in predicting cooperation and generosity than MFQ-2 (r’s ranging from < 0.01 to 0.09).

Exploratory analysis

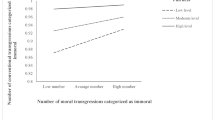

To further explore whether the moral foundations measured by MFQ-2 tap onto a single or two-factor structure, we ran a two-step cluster analysis. Results revealed two clusters having similar sizes (nC1 = 533; nC2 = 566). In line with the CFA analyses, moral foundations did not differ from each other in clustering participants. As presented in Fig. 1, the first cluster comprised participants with high endorsement of all foundations, while the second cluster was composed of participants with low endorsement of moral foundations. The most important predictor was authority, followed by loyalty, care, purity, proportionality, and equality, supporting the view that moral foundations can be clustered based on a single higher-order factor.

Discussion

This research provides the first independent empirical support for the updated version of MFQ, corroborating its basic assumptions in a predominantly Muslim country. The fit-values of MFQ-2 indicate a six-factor structure and tend to better represent laypeople’s moral psychology than the original five-factor structure, whose limitations have been previously identified (see Yilmaz & Saribay, 2018). Although MFQ-2 predicted criterion variables better than MAC-Q’s seven-factor structure, fit values were similar. However, MAC-Q outperformed MFQ-2 in predicting actual moral behavior involving generosity and cooperation.

Hence, the first independent test of the updated version of MFQ suggests a valid tool to capture lay moral psychology in a predominantly Muslim country. Nevertheless, the alternative model provided by MAC-Q seems equally effective in this task. Critically, our findings suggest that the six dimensions can be reduced to a single higher-order dimension (e.g., morality) as in the MAC-Q (i.e., cooperation), problematizing the standard distinction between individualizing and binding foundations. These findings are generally consistent with the literature (e.g., Atari et al., 2023; Curry et al., 2019; Yilmaz et al., 2021), which showed that while both the six-factor solution of MFQ-2 and the seven-factor solution of MAC-Q are supported across the various cultures observed, the same cannot be said for the standard two-factor solution of moral foundations. Another important limitation of MFQ-2, shown here for the first time, is its relative inability to predict actual moral behavior compared with MAC-Q. While the MFQ-2 and MAC-Q are valuable empirical instruments for measuring the morality construct, it is crucial to acknowledge their inherent limitations, including measurement error and varying precision. It is essential to recognize that the validity of these measures is a matter of degree, emphasizing the statistical nature of the conclusions drawn from their use. It is imperative to exercise caution in making inferences about real moral intuitions solely based on the factor structures obtained. Hence, it is essential to interpret the current findings with the acknowledgment that both the MFQ-2 and the MAC-Q serve as indirect measures of morality concerning intentions rather than direct assessments of moral intuitions themselves.

Intention-behavior gap

The relationship between moral judgment (e.g., “foundations”) and moral behavior (e.g., cooperation), at least as proposed in the literature (e.g., Curry et al., 2019; Graham & Haidt, 2010), is not well-understood. Studies using MFQ or MAC-Q (Atari et al., 2023; Curry et al., 2019; Yilmaz et al., 2021) have not explored how moral judgments (e.g., intentions) relate to actual moral behavior. Such exclusive reliance on intention measures can bias the scientific study of morality due to “gaps” between behavior and intention, known since the classic work of LaPiere (1934). There is growing evidence that this gap also exists in the field of moral psychology (Camerer et al., 2018; Sheeran & Webb, 2016). For example, Bostyn et al. (2018) showed that standard and behavioral responses in the classic trolley dilemma could often diverge.

The intention-behavior gap can be particularly significant in moral psychology because moral actions involving generosity and cooperation are particularly open to social influence and desirable responses (Clarkson et al., 2022). Yet, the actual size of this gap in studies on moral foundations remains unclear, in large part due to the underutilization of behavioral measures in moral psychology (Ellemers et al., 2019). We know of only one prior study that has measured both moral foundations and actual moral behavior. Using a cross-sectional and correlational design on a WEIRD sample, Clark et al. (2017) showed that the two-factor structure can help predict behavior in economic games, which could be interpreted as a sign of a small gap. However, this study by (Clark et al., 2017) was not preregistered, and its sample size was small. Using a large-scale preregistered study, we showed that, despite significant correlations between MFQ-2 and MAC-Q scores on the one hand and generosity and cooperation behavior on the other, the effect sizes were smaller for MFQ-2 than MAC-Q. Hence, although our results provide evidence for the predictive validity of MFQ-2, they also raise questions about its usefulness in predicting behavior across moral domains. Future studies should attempt to conceptually replicate our findings using different operationalization of moral foundations and moral behaviors.

Equality vs. proportionality

The updated version of the Moral Foundations Theory proposes equality and proportionality as separate constructs (Atari et al., 2023). For instance, proportionality demonstrates stronger relationships with reciprocity and fairness dimensions of MAC-Q than equality. Those who value equality tend to report lower average scores in verbal, analytical thinking skills, while those who value proportionality tend to report higher average scores. Only equality shows a positive relationship with religiosity, while neither dimension explains political ideology. Our findings agree with previous studies showing a negative relationship between fairness and right-wing political orientation in Türkiye (Yalçındağ et al., 2019; Yilmaz et al., 2016a; Yılmaz et al., 2016b) but are inconsistent with others (Yilmaz et al., 2016c). In larger and more representative samples, these relationships turn out nonsignificant (e.g., Yilmaz et al., 2016c), while negative relationships were reported in convenience and student-majority samples (e.g., Yilmaz et al., 2016a; Yılmaz et al., 2016b). Considering that the sample in this study represents Türkiye in age and gender, the nonsignificant results with ideology are consistent with general observations in the literature. Significant positive correlations have been reported with both religiosity and right-wing ideology, as in previous studies (e.g., Yalçındağ et al., 2019), in dimensions traditionally known as binding foundations. Furthermore, considering that religiosity holds more importance than ideology in Türkiye (e.g., Rubin & Çarkoğlu, 2013), the larger correlation coefficients related to religiosity can be understood in the context of Turkish cultural norms.

Moral relevance vs. judgment

The updated version of MFT, unlike the original version of the theory, has shown good fit values above standard criteria in a predominantly Muslim country, indicating that it can be used in future studies. We note that the comparisons made here are between the relevance form of MAC-Q and the judgment form of MFQ-2. MFQ-2 has abandoned the distinction between relevance and judgment and has converted all items into judgment form, which we used. As pointed out by Curry et al. (2019), the problem of combining relevance and judgment forms in MFQ also applies to MAC-Q. We exclusively used the relevance subscale of MAC-Q because this was the only subscale that performed well in both Curry et al.‘s original (2019) and Yilmaz et al.‘s (2021) independent standardization studies. However, a new scale for MAC-Q that is solely based on judgment is needed to provide a more precise comparison with MFQ-2.

Theoretical and practical contributions

The findings of the present study offer valuable insights that contribute to both theoretical advancements and practical implications within the existing literature. Firstly, our study aligns with Atari et al.‘s (2023) criticism of the foundational premises of fairness within the MFT, endorsing their suggestion of two distinct foundations, equity and proportionality, thus reinforcing the notion that fairness alone lacks adequacy in encompassing nuanced differences. Specifically, it seems that conflating equality and proportionality as fairness within a singular dimension fails to represent diverse cultural viewpoints accurately. This highlights the necessity for cross-cultural studies of moral judgments to differentiate between these foundations. Our findings further validate the conclusions drawn by Atari et al. (2023) in the context of Türkiye, a non-WEIRD country. We demonstrated that the Turkish version of MFQ-2 can be used to measure moral judgment endorsements with the six-factor model, expanding the tool’s applicability beyond its initial validation.

Our study additionally reveals that while moral endorsement scores derived from the MFQ-2 predict moral behaviors, the MAC-Q demonstrates superior predictive efficacy. This finding corroborates prior research, which similarly found that the MAC-Q outperforms the original MFQ-1 in predicting prosocial intentions (e.g., Yilmaz et al., 2021). Thus, despite the MFQ-2 representing an improvement to the theoretical structure proposed by the MFT, it nonetheless exhibits shortcomings in predicting prosocial tendencies, thereby bolstering criticisms against it in favor of the MAC-Q.

Limitations and future directions

Our non-Western sample provided evidence for the validity of MFQ-2. However, unlike most previous research on the topic that relies on convenience samples (e.g., Atari et al., 2023; Curry et al., 2019; Yilmaz et al., 2021), the present study used a quota sample that is representative of the Turkish population in age and gender. Future studies should aim to use probabilistic samples to increase the external validity of their tests.

Another claim of the theory that awaits testing is the assertion that, although moral foundations are evolutionary adaptations, they still are influenced by environmental factors. For instance, experimental paradigms can be employed to examine how resource scarcity, known to reduce cooperation (Roux et al., 2015), affects the importance given to different foundations. However, it is not clear whether the foundations proposed by MFQ-2 are directly related to cooperation as in MAC. The weak associations of MFQ-2 with generosity and cooperation found in our study underscore this theoretical ambiguity. Future studies can further investigate this relationship longitudinally.

Another limitation involves the potential for translation issues with the questionnaire items, which could introduce noise into the data. However, it is noteworthy that the MFQ-2 demonstrated favorable fit indices, suggesting that this concern can be mitigated.

Conclusion

In sum, our findings support conceptualizing moral foundations as theorized by MFT and as measured by MFQ-2. Future research should continue to compare this theory with new alternatives, such as MAC, using longitudinal designs and observing actual moral behavior. Therefore, it is of great importance to develop and validate psychometric tools that are thought to measure the structures proposed by contemporary moral theories.

Data availability

All data and preregistration forms are accessible at https://osf.io/63ucs/?view_only=a49f8567f17e469b8eed84caacfc010e.

Notes

Due to the differences in estimation techniques and model specifications, we could not directly compare the two models (i.e., MAC-Q and MFQ-2). Instead, we interpret that both models provided excellent fit to the data on the same sample suggesting that both scales worked as intended.

We also conducted exploratory factor analysis on MFQ-2 items. Results revealed a single factor with an eigenvalue greater than one (eigenvalue = 4.39, explained variance = 73.16%). Parallel analysis also confirmed a single-factor solution.

Zero-order correlation between equality and cooperation was not significant yet regression coefficient was negative and significant implying a statistical suppression. Our regression models were based on a theoretical perspective, we therefore kept the models as it was. Besides, since detecting the source of statistical suppression and interpreting such suppressive relationship after the fact is not important (Ludlow & Klein, 2014), we only reported the multiple regression results for transparency purposes, however we did not discuss the multiple regression findings indicating suppressor relationships (i.e., stronger regression coefficient as compared to zero-order correlation).

Similar statistical suppression was observed in predicting political ideology and religiosity using MFQ-2.

References

Atari, M., Haidt, J., Graham, J., Koleva, S., Stevens, S. T., & Dehghani, M. (2023). Morality beyond the WEIRD: How the nomological network of morality varies across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 125(5), 1157–1188. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000470

Barends, A. J., De Vries, R. E., & Van Vugt, M. (2019). Power influences the expression of honesty-humility: The power-exploitation affordances hypothesis. Journal of Research in Personality, 82, 103856. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2019.103856

Barr, A., & Zeitlin, A. (2010). Dictator games in the lab and in nature: External validity tested and investigated in Ugandan primary schools. ideas.repec.org. https://ideas.repec.org/p/csa/wpaper/2010-11.html

Bostyn, D. H., Sevenhant, S., & Roets, A. (2018). Of mice, men, and trolleys: Hypothetical judgment versus real-life behavior in trolley-style moral dilemmas. Psychological Science, 29(7), 1084–1093. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617752640

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. The Guilford.

Camerer, C. F., Dreber, A., Holzmeister, F., Ho, T. H., Huber, J., Johannesson, M., Kirchler, M., Nave, G., Nosek, B. A., Pfeiffer, T., Altmejd, A., Buttrick, N., Chan, T., Chen, Y., Forsell, E., Gampa, A., Heikensten, E., Hummer, L., Imai, T., & Wu, H. (2018). Evaluating the replicability of social science experiments in nature and science between 2010 and 2015. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(9), 637–644. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0399-z

Carleton, R. N., Norton, M. A. P. J., & Asmundson, G. J. G. (2007). Fearing the unknown: A short version of the intolerance of uncertainty scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(1), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.014

Chan, E. Y. (2021). Moral foundations underlying behavioral compliance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, 110463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110463

Charness, G., Gneezy, U., & Halladay, B. (2016). Experimental methods: Pay one or pay all. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 131, 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2016.08.010

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Clark, M. S., Lemay, E. P., & Reis, H. T. (2017). Other people as situations: Relational context shapes psychological phenomena. Oxford Handbook of Situations. Oxford University Press.

Clarkson, E., Jasper, J. D., & Gugle, B. (2022). Differences in moral judgment predict behavior in a Covid triage game scenario. Personality and Individual Differences, 195, 111671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111671

Clifford, S., & Jerit, J. (2013). How words do the work of politics: Moral foundations Theory and the debate over Stem Cell Research. The Journal of Politics, 75(3), 659–671. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022381613000492

Crone, D., & Laham, S. M. (2015). Multiple moral foundations predict responses to sacrificial dilemmas. Personality and Individual Differences, 85, 60–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.04.041

Curry, O. S. (2016). Morality as cooperation: A problem-centred approach. In Shackelford, T. K. & Hansen, R. D. (Eds.), The Evolution of Morality (pp. 27–51). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19671-8_2

Curry, O. S., Chesters, J., M., & Van Lissa, C. J. (2019). Mapping morality with a compass: Testing the theory of ‘morality-as-cooperation’ with a new questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality, 78, 106–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.10.008

Dalbert, C. (1999). The world is more just for me than generally: About the personal belief in a just world scale’s validity. Social Justice Research, 12(2), 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022091609047

Darley, J. M., & Shultz, T. R. (1990). Moral rules: Their content and acquisition. Annual Review of Psychology, 41(1), 525–556. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ps.41.020190.002521

Davies, C. L., Sibley, C. G., & Liu, J. H. (2014). Confirmatory factor analysis of the moral foundations questionnaire. Social Psychology, 45(6), 431–436. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000201

Dawson, S., & Tyson, G. (2012). Will morality or political ideology determine attitudes to Climate Change? Australian Community Psychologist: The Official Journal of the APS College of Community Psychologists, 24(2), 8–25.

Dawson, K. J., Han, H., & Choi, Y. (2021). How are moral foundations associated with empathic traits and moral identity? Current Psychology, 42(13), 10836–10848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02372-5

De Buck, A., & Pauwels, L. (2023). Moral foundations Questionnaire and Moral foundations Sacredness Scale: Assessing the factorial structure of the Dutch translations. Psychologica Belgica, 63(1), 92–104. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb.1188

Dickinson, J. L., McLeod, P. L., Bloomfield, R. J., & Allred, S. B. (2016). Which moral foundations predict willingness to make lifestyle changes to avert climate change in the USA? PLoS ONE, 11(10), e0163852. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163852

Doğruyol, B., Alper, S., & Yilmaz, O. (2019). The five-factor model of the moral foundations theory is stable across WEIRD and non-WEIRD cultures. Personality and Individual Differences, 151, 109547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109547

Du, J. (2019). Validation of the Moral foundations questionnaire with three Chinese ethnic groups. Social Behavior and Personality, 47(8), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.8009

Ellemers, N., Van Der Toorn, J., Paunov, Y., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2019). The psychology of morality: A review and analysis of empirical studies published from 1940 through 2017. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 23(4), 332–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868318811759

Englmaier, F., & Gebhardt, G. (2011). Free-Riding in the lab and in the field. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1946756

Fehr, E., & Leibbrandt, A. (2008). Cooperativeness and impatience in the tragedy of the commons. Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1214914

Franks, A. S., & Scherr, K. C. (2015). Using moral foundations to predict voting behavior: Regression models from the 2012 U.S. Presidential Election. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 15(1), 213–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12074

Frederick, S. (2005). Cognitive reflection and decision making. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(4), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533005775196732

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, W. B. (2003). A very brief measure of the big-five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 504–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1

Graham, J., & Haidt, J. (2010). Beyond beliefs: Religions bind individuals into moral communities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(1), 140–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868309353415

Graham, J., Haidt, J., & Nosek, B. A. (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 1029–1046. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015141

Graham, J., Nosek, B. A., Haidt, J., Iyer, R., Koleva, S., & Ditto, P. H. (2011). Mapping the moral domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 366–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021847

Hadarics, M., & Kende, A. (2017). A closer look at intergroup threat within the dual process model framework: The mediating role of moral foundations. Psychological Thought, 10(1), 167–177. https://doi.org/10.5964/psyct.v10i1.210

Haidt, J., & Graham, J. (2007). When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Social Justice Research, 20(1), 98–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-007-0034-z

Haidt, J., Koller, S. H., & Dias, M. G. (1993). Affect, culture, and morality, or is it wrong to eat your dog? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(4), 613–628. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.4.613

Harper, C. A., & Rhodes, D. (2021). Reanalysing the factor structure of the moral foundations questionnaire. British Journal of Social Psychology, 60(4), 1303–1329. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12452

Hilbig, B. E., Zettler, I., & Heydasch, T. (2012). Personality, punishment and public goods: Strategic shifts towards cooperation as a matter of dispositional honesty–humility. European Journal of Personality, 26(3), 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.830

Iurino, K., & Saucier, G. (2018). Testing measurement invariance of the Moral foundations questionnaire across 27 countries. Assessment, 27(2), 365–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191118817916

Iyer, R., Graham, J., Koleva, S., Ditto, P. H., & Haidt, J. (2010). Beyond identity politics: Moral psychology and the 2008 democratic primary. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 10(1), 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-2415.2010.01203.x

Jansson, J., & Dorrepaal, E. (2015). Personal norms for dealing with climate change: Results from a survey using moral foundations theory. Sustainable Development, 23(6), 381–395. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.1598

Kohlberg, L. (1969). Stage and sequence: The cognitive developmental approach to socialization. In D. Goslin (Ed.), Handbook of socialization theory and research (pp. 347–480). Rand McNally.

Koleva, S., Graham, J., Iyer, R., Ditto, P. H., & Haidt, J. (2012). Tracing the threads: How five moral concerns (especially purity) help explain culture war attitudes. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(2), 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2012.01.006

Lakens, D. (2022). Sample size justification. Collabra, 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.33267

LaPiere, R. T. (1934). Attitudes vs. Actions. Social Forces, 13(2), 230–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/2570339

Ludlow, L., & Klein, K. (2014). Suppressor variables: The difference between ‘Is’ versus ‘Acting as’. Journal of Statistics Education, 22(2), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691898.2014.11889703

Moreira, L. V., De Souza, M. L., & Guerra, V. M. (2019). Validity evidence of a Brazilian version of the moral foundations questionnaire. Psicologia: Teoria E Pesquisa, 35. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102.3772e35513

Morin, A. J. S., & Asparouhov, T. (2018). Estimation of a hierarchical exploratory structural equation model (ESEM) using ESEM-within-CFA. Substantive Methodological Synergy Research Laboratory.

Morin, A. J. S., Myers, N. D., & Lee, S. (2020). Modern factor analytic techniques: Bifactor models, exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM), and bifactor-ESEM. In G. Tenenbaum & R. C. Eklund (Eds.), Handbook of sport psychology (1st ed., pp. 1044–1073). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119568124.ch51

Moshagen, M., & Erdfelder, E. (2016). A new strategy for testing structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 23(1), 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.950896

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables: User’s guide (Version 8). Authors.

Nichols, S. (2002). Norms with feeling: Towards a psychological account of moral judgment. Cognition, 84(2), 221–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-0277(02)00048-3

Nilsson, A., & Erlandsson, A. (2015). The Moral foundations taxonomy: Structural validity and relation to political ideology in Sweden. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 28–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.049

Nilsson, A., Erlandsson, A., & Västfjäll, D. (2020). Moral foundations theory and the psychology of charitable giving. European Journal of Personality, 34(3), 431–447. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2256

Piaget, J. (1965). The moral judgment of the child. Harcourt.

Roux, C., Goldsmith, K., & Bonezzi, A. (2015). On the psychology of scarcity: When reminders of resource scarcity promote selfish (and generous) behavior. Journal of Consumer Research., ucv048. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucv048

Różycka-Tran, J., Boski, P., & Wojciszke, B. (2015). Belief in a zero-sum game as a social axiom: A 37-nation study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 46(4), 525–548. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022115572226

Różycka-Tran, J., Jurek, P., Olech, M., Piotrowski, J., & Żemojtel‐Piotrowska, M. (2019). Measurement invariance of the belief in a zero‐sum game scale across 36 countries. International Journal of Psychology, 54(3), 406–413. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12470

Rubin, B., & Çarkoglu, A. (Eds.). (2013). Religion and politics in Turkey. Routledge.

Sariçam, H. (2014). Beli̇rsi̇zli̇ğe tahammülsüzlük ölçeği̇ (btö-12) Türkçe formu: Geçerli̇k ve güveni̇rli̇k çalişmasi. Route Educational and Social Science Journal, 1(3), 148–148. https://doi.org/10.17121/ressjournal.109

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (pp. 1–65). https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60281-6

Shane, S. (1995). Uncertainty avoidance and the preference for innovation championing roles. Journal of International Business Studies, 26(1), 47–68. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490165

Sheeran, P., & Webb, T. L. (2016). The intention-behavior gap: The intention-behavior gap. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(9), 503–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12265

Shweder, R. A., Much, N. C., Mahapatra, M., & Park, L. (2013). The ‘big three’ of morality (autonomy, community, divinity) and the ‘big three’ explanations of suffering. In A. M. Brandt & P. Rozin (Eds.), Morality and health (pp. 119–169). Routledge.

Smith, K. B., Alford, J. R., Hibbing, J. R., Martin, N. G., & Hatemi, P. K. (2017). Intuitive ethics and political orientations: Testing moral foundations as a theory of political ideology. American Journal of Political Science, 61(2), 424–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12255

Stoop, J. (2013). From the lab to the field: Envelopes, dictators and manners. Experimental Economics, 17(2), 304–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-013-9368-6

Strupp-Levitsky, M., Noorbaloochi, S., Shipley, A., & Jost, J. T. (2020). Moral foundations as the product of motivated social cognition: Empathy and other psychological underpinnings of ideological divergence in individualizing and binding concerns. PLoS ONE, 15(11), e0241144. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241144

Süssenbach, P., Rees, J., & Gollwitzer, M. (2019). When the going gets tough, individualizers get going: On the relationship between moral foundations and prosociality. Personality and Individual Differences, 136, 122–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.01.019

Thomson, K. S., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2016). Investigating an alternate form of the cognitive reflection test. Judgment and Decision Making, 11(1), 99–113. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1930297500007622

Vainio, A., & Mäkiniemi, J. (2016). How are moral foundations associated with climate-friendly consumption? Journal of Agricultural & Environmental Ethics, 29(2), 265–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-016-9601-3

Van Zyl, L. E., & Ten Klooster, P. M. (2022). Exploratory structural equation modeling: Practical guidelines and tutorial with a convenient online tool for mplus. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 795672. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.795672

Webb, T. L., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 132(2), 249. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249

Welsch, H. (2020). Moral foundations and voluntary public good provision: The case of climate change. Ecological Economics, 175, 106696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106696

Yalçındağ, B., Özkan, T., Cesur, S., Yılmaz, O., Tepe, B., Piyale, Z. E., Biten, A. F., & Sunar, D. (2017). An investigation of moral foundations theory in Turkey using different measures. Current Psychology, 38(2), 440–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9618-4

Yalçındağ, B., Özkan, T., Cesur, S., Yilmaz, O., Tepe, B., Piyale, Z. E., Biten, A. F., & Sunar, D. (2019). An investigation of moral foundations theory in Turkey using different measures. Current Psychology, 38(2), 440–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9618-4

Yilmaz, O., & Saribay, S. A. (2018). Moral foundations explain unique variance in political ideology beyond resistance to change and opposition to equality. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 22(8), 1124–1138. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430218781012

Yilmaz, O., Harma, M., Bahçekapili, H. G., & Cesur, S. (2016a). Validation of the Moral foundations questionnaire in Turkey and its relation to cultural schemas of individualism and collectivism. Personality and Individual Differences, 99, 149–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.090

Yılmaz, O., Sarıbay, S. A., Bahçekapılı, H. G., & Harma, M. (2016b). Political orientations, ideological self-categorizations, party preferences, and moral foundations of young Turkish voters. Turkish Studies, 17(4), 544–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/14683849.2016.1221312

Yilmaz, O., Erdoğan, E., & Saribay, A. (2016c). Türkiye’deki Ahlaki Temeller ve Politik İdeoloji: Bir Kümeleme Analizi Çalışması (Vol. 1). Sosyal Psikoloji Kongresi.

Yilmaz, O., Harma, M., & Doğruyol, B. (2021). Validation of morality as cooperation questionnaire in Turkey, and its relation to prosociality, ideology, and resource scarcity. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 37(2), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000627

Zakharin, M., & Bates, T. C. (2021). Remapping the foundations of morality: Well-fitting structural model of the moral foundations questionnaire. PLoS ONE, 16(10), e0258910. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258910

Zakharin, M., & Bates, T. C. (2023). Moral foundations theory: Validation and replication of the MFQ-2. Personality and Individual Differences, 214, 112339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2023.112339

Acknowledgements

Onurcan Yilmaz acknowledges support under the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TÜBİTAK) ARDEB 1001 Grant (Project No: 121K638).

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dogruyol, B., Velioglu, İ., Bayrak, F. et al. Validation of the moral foundations questionnaire-2 in the Turkish context: exploring its relationship with moral behavior. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06097-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06097-z