Abstract

The Gaia program is a 12-week mindfulness intervention based on cultivating body, emotional, and ecological self-awareness, which has been shown to be effective in reducing children’s and adolescents’ internalizing problems, and improving psychological well-being, and psychological distress in early adolescents. To clarify the psychological processes underlying mindfulness effects on mental health among adolescents, the present study aimed to examine whether emotion regulation strategies (i.e., cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression) may be considered as key processes linking the Gaia program effects to improvements in psychological distress and well-being. A total of 361 adolescents (mean age 14 years) were randomly assigned to one of two groups: the Gaia program (i.e., experimental group; N = 210) and waiting list (i.e., control group; N = 151). Measures were administered at three time points, approximately every three months: one week before treatment, one week after treatment, and three months after treatment. Using a structural equation model (SEM), we found that the Gaia Program had a positive and significant indirect effect on psychological well-being only via cognitive reappraisal as measured at follow-up [B = 0.181, 95% C.I. (0.012; 0.395)], whereas no significant indirect effects were found on psychological distress through cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. Findings from this study provide evidence of key emotional processes underlying the effects of a mindfulness intervention on positive but not negative psychological outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescence is a crucial stage of human development, wherein physical and psychological challenges may increase the risk of ill-being (e.g., Solmi et al., 2021). Adolescents begin to explore the most appropriate ways to regulate their emotions, dealing with many developmental changes that require an effective emotional response management (e.g., van Lissa, 2022). Although research has traditionally focused on the reduction of ill-being (e.g., depression or anxiety; Clarke & Currie, 2009), there is wide consensus that illness is not a sufficient, even if necessary, criterion to define mental health. In this vein, the conceptualization of well-being and distress as mutually exclusive has been challenged by clinical research and they are now considered two independent constructs (i.e., the absence of psychological distress does not necessarily imply the presence of well-being and vice versa; e.g., Fava & Guidi, 2020). Moreover, high levels of psychological well-being during the developmental process are considered the hallmark of optimal functioning (Ruini et al., 2009). Thus, it is of relevance to investigate the effectiveness of psychological interventions in a comprehensive approach encompassing both the promotion of psychological well-being and the prevention or reduction of psychological distress in adolescents.

Mindfulness is a promising therapeutic avenue since it has been associated with higher well-being (Garland et al., 2015a), adaptive emotion regulation strategies (Garland et al., 2017), and reduction of psychological distress (Garland et al., 2011). Recent studies investigated the effects of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) on youths’ and adolescents’ mental health. For example, Tan and Martin (2015) showed that adolescents in a mindfulness-based group program reported lower levels of mental distress and psychological inflexibility, as well as higher levels of mindfulness, self-esteem, and mental health at post-treatment and at 3-months follow up when compared with the control group. Moreover, adolescents in contemplation and meditation training reported higher levels of psychological well-being and lower levels of negative affect; however, no effects were observed on positive affect and life satisfaction (Bach & Guse, 2015). Conversely, a mindfulness training did not improve psychological well-being when compared with the control group; however, improvements in psychological well-being were observed in association with a more time spent engaging in home practice of meditation exercises (Huppert & Johnson, 2010). Also, in a recent meta-analytic study on the effects of mindfulness on psychological distress and well-being of children and adolescents, it has been reported that MBIs had a small effect on anxiety, depression, and stress, and no significant effects were found on well-being (Zhang et al., 2022). These authors suggested that further investigations are needed to determine how to increase the stress-buffering effects of MBIs and the potential role in enhancing psychological well-being.

Over the past decades, MBIs have been adapted for the school context. Adolescents spend most of their time at school, wherein psychological well-being, character strengths, and social and emotional skills may be increased, as well as psychological symptoms and psychosocial difficulties may be prevented (Seligman et al., 2009). Thus, school settings can play an important role on a variety of health and scholastic outcomes during adolescence. In this context, mindfulness-based school interventions have been shown to be effective in improving several health outcomes, including psychological distress, anxiety, and depression (Dunning et al., 2019), as well as psychological well-being (Cilar et al., 2020).

Why is mindfulness related to psychological distress and well-being in adolescents? According to Shapiro et al’s. (2006) model, mindfulness practice leads to a shift in perspective (i.e., reperceiving), a meta-mechanism overarching additional direct mechanisms, namely self-regulation, values clarification, cognitive, emotional and behavioral flexibility, and exposure. Based on this model, Klingbeil et al. (2017) synthesized the effects of MBIs on potential therapeutic processes in youth. Overall, MBIs had positive effects on all processes, with the largest effect on mindfulness (i.e., the first-order therapeutic process) and lowest effects on meta-cognition, cognitive flexibility, and emotional/behavioral regulation (i.e., second-order therapeutic processes; Klingbeil et al., 2017). However, these results are based on intervention studies which consider the therapeutic processes as outcome variables (Klingbeil et al., 2017) and few studies investigated these and other potential processes through mediation analysis (Tudor et al., 2022), which is required to understand how interventions exert their effects. A recent scoping review found that only five studies investigated potential mediators of the relationship between school-based mindfulness interventions and adolescents’ outcomes (Tudor et al., 2022). Most of these studies included only two time-points and did not study change in the mediator prior to the change in the outcome (Tudor et al., 2022). In sum, the investigation of processes underlying the effects of school-based mindfulness intervention is still in its infancy and well-designed studies with three-time points evaluations are needed (Tudor et al., 2022).

Adolescence is a pivotal stage for the development of emotion regulation, which parallels developing regulatory neural circuitry. According to the process model, expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal are the most commonly used emotion regulation strategies (Gross, 2014). Despite a wide consensus on emotion regulation as a critical process linking mindfulness to psychological outcomes, the nature of the relationship between mindfulness and emotion regulation strategies is still inconsistent across theorists. Some researchers considered mindfulness as a mere form of non-judgmental awareness and non-conceptual attention, which would extinguish evaluative processes (e.g., Chambers et al., 2009). According to this perspective, “emotions are just emotions and there is no need to regulate them” (Nyklíček, 2011; p. 106). Conversely, others suggested that mindfulness promotes evaluative processes (i.e., cognitive insight) allowing one to reframe meaning of experiences (Garland et al., 2015a). Whereas the former view poses cognitive reappraisal as antithetical to mindfulness, the latter (i.e., the mindfulness-to-meaning theory) posits that cognitive reappraisal is a critical process towards psychological well-being (Garland et al., 2015a) and distress (Garland et al., 2011). Accordingly, “mindfulness allows one to decenter from stress appraisals into a metacognitive state of awareness, resulting in broadened attention to novel information that accommodates a reappraisal of life circumstances” (Garland et al., 2015b; p. 377). Consistently, Garland et al. (2017), found that broaden awareness, as measured at six months post-intervention, predicted increases in cognitive reappraisal after nine months post-intervention, which, in turn, led to higher level of positive affect, as measured at 12 months post-intervention. In a similar vein, mindfulness may be posed to be antithetical to emotion suppression, in that there is an emphasis on non-judgmental acceptance and awareness of the experience, regardless of its valence and intensity; thus, a mindful individual might accept thoughts and emotions, rather than reflexively act on them (Chambers et al., 2009). As pointed out by Nyklíček (2011), however, it is worth to distinguish between the suppression of experience and the suppression of expression. Whereas the suppression of the emotional experience is incompatible with mindfulness, since mindfulness embraces any experience, expressive suppression is not per se incompatible with mindfulness, since it may be viewed as a “natural by-product of mindfulness” (Nyklíček, 2011; p. 106). Indeed, the author posited that a mindful individual who has learned to accept the emotional experience through mindfulness meditation, could also choose to not express an emotion immediately, since it could be seen as transitory and changeable, not tied to the present moment, but more to the projection of past personal memories.

A paucity of studies investigated the relationship between mindfulness, emotion regulation strategies (i.e., cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression), and psychological outcomes in youth. For example, two observational studies found that expressive suppression, but not cognitive reappraisal, mediated the association between dispositional mindfulness and negative functioning (e.g., depression and anxiety) in middle (Ma & Fang, 2019) and high school students (Pepping et al., 2016). Moreover, Fung et al. (2019) tested the efficacy of a school-based mindfulness intervention in ethnic minority youth. They found that expressive suppression and rumination, but not cognitive reappraisal, explained the improvements in youth internalizing problems and stress following the intervention. Overall, these results may suggest that cognitive reappraisal is not a relevant process, in that mindfulness wouldn’t promote evaluative processes which may potentially lead to desired outcomes. It is worth noting, however, that these results are based on outcomes related to negative functioning. There is evidence showing that adaptive emotion regulation strategies (e.g., cognitive reappraisal) have weaker or null associations with psychopathology than maladaptive strategies (e.g., expressive suppression; Aldao et al., 2010; Aldao & Nole-Hoeksema, 2012). When considering well-being outcomes, some evidence suggests an opposite trend; for instance, reappraisal, but not suppression, was associated with eudaimonic and hedonic well-being (Kraiss et al., 2020). Overall, these results emphasize the need for considering both well-being and ill-being outcomes.

Rationale and hypotheses

There is strong evidence suggesting that emotion regulation plays a pivotal role in youth’s psychological distress. Meta-analytic results showed that increased use of cognitive reappraisal was negatively associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms in adolescents, whereas suppression was positively associated (Schäfer et al., 2017). Although mindfulness was found to be effective in improving emotional/behavioral strategies (Klingbeil et al., 2017), whether reappraisal and suppression reflect relevant processes linking mindfulness to psychological distress has been investigated by few observational and intervention studies (Fung et al., 2019; Ma & Fang, 2019; Pepping et al., 2016). According to this initial evidence, mindfulness would lead to improvements of distress through a decreased use of expressive suppression, but not through an increased use of cognitive reappraisal.

Moreover, there is a paucity of research specifically investigating the predictive role of emotion regulation strategies on psychological well-being in healthy adolescents. It is worth noting that most research on adolescents’ emotion regulation focused on clinical samples (Kraiss et al., 2020) and did not specifically examine psychological well-being (e.g., De France & Hollenstein, 2019; Verzelletti et al., 2016). Furthermore, little is known about the most specific emotion regulation strategy may be considered a key process linking mindfulness to psychological well-being, since, to the best of our knowledge, such mediating role of adolescents’ expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal has never been investigated.

In the current study, we build on these gaps by investigating cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression as potential processes that may explain the effects of the Gaia program (i.e., a school-based mindfulness intervention) on psychological distress and well-being. The Gaia Program was already found to be effective in improving several outcomes (e.g., internalizing, externalizing problems; Ghiroldi et al., 2020; Scafuto et al., 2022). The program integrated insight from previous research based on the correlation between mindfulness, relatedness to nature and sense of global community (Scafuto, 2021). Specifically, the first and the second modules of the Gaia program target concentrative meditation on body sensations (e.g. body scan); the third module is focused on the relationship between these sensations and emotions, and between emotions and events that co-occur (answering to questions such as “When do you usually feel this emotion/ body sensation?”). It is encouraged the verbal description of one’s sensations (e.g. “a sense of a nod in the throat”), the process of naming and identifying emotions (e.g. “such as fear”) and the sharing with others, also through the so-called psychosomatic drawing. The fourth module instead is focused on ecological self-awareness, targeting one’s identification with nature (e.g. exercise of being a tree; being a planet; and the reading of the Earth Charter; Ghiroldi et al., 2020).

Why do we hypothesize that Gaia Program affects emotion regulation and by this, psychological wellbeing and distress? One of the main aims of the Gaia program is to direct voluntary attention to the physiological condition of the body (Nani et al., 2019). Hence, this practice may involve interoceptive sensibility, that is the capacity to sense, interpret, and consciously integrate signals related to the physiological condition of the body (Garfinkel & Critchley, 2013), and which has been associated with effective emotion regulation (Price & Hooven, 2018; Tan et al., 2023). The intervention could promote mind-body connection by initiating from intentional mental processing at the level of the cerebral cortex (top-down; Taylor et al., 2010). Indeed, top-down processes can be enhanced by the verbal description of one’s sensations and by the identification of emotions (Taylor et al., 2010).

Since emotion regulation involves an effective communication between the body, thoughts, and feelings (Price & Hooven, 2018), we hypothesized that targeting interoceptive sensibility and mind-body connection through the Gaia program may sustain an effective emotion regulation (e.g., the ability to modify evaluation of stressful events or to act in a proactive way to change the emotional experience). Specifically, we derived the following hypotheses:

-

(1)

consistently with previous findings showing that expressive suppression mediated the association between mindfulness and psychological distress (Fung et al., 2019; Ma & Fang, 2019; Pepping et al., 2016), we hypothesized that participating to the Gaia program would reduce the use of expressive suppression, which in turn would lead to lower levels of psychological distress (H1);

-

(2)

building on previous studies with adults showing no association between expressive suppression and psychological well-being (Kraiss et al., 2020), we aim to extend these results to adolescents by hypothesizing that the Gaia program would reduce the use of expressive suppression, but the latter would not lead to higher levels of psychological well-being or such effects would be small (H2);

-

(3)

in line with the mindfulness-to-meaning theory (Garland et al., 2015a) and previous studies showing significant associations between cognitive reappraisal and psychological well-being in adults, we aim to extend these results to adolescents by hypothesizing that the Gaia program would increase the use of cognitive reappraisal, which would lead to higher levels of psychological well-being (H3);

-

(4)

since cognitive reappraisal had weaker or null associations with psychological distress compared to expressive suppression (Aldao et al., 2010; Aldao & Nole-Hoeksema, 2012), we hypothesized that the Gaia program would increase the use of cognitive reappraisal, but the latter would not lead to lower levels of psychological distress or such effects would be small (H4).

Method

Participants

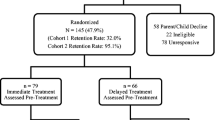

This research is part of a larger prospective study investigating the effects of the Gaia program in youth (Ghiroldi et al., 2020; Scafuto et al., 2022). A sample of 361 participants (sex: females = 190; males = 168) with an average age of 13.45 (SD = 2.16; min-max: 10; 20) participated in the study. About 46% of students attended the 8th-grade school (Females 49%, Males 51%), while about 54% of students were from higher school levels (Females 57%, Males 43%). Regarding geographical distribution, participants involved in the study were from school institutes in different regions of Italy: about 45% of students were from school institutes in the North of Italy (i.e., Crema, Genova, Rosolina), and about 55% of students were from school institutes in the Center-South of Italy (i.e., Ancona, Falconara Marittima, Frascati, Jesi, Piglio, Senigallia).

To estimate the optimal sample size and statistical power of the target mediation effects, we used the method developed by Wang and Rhemtulla (2021). We made the following assumptions about population parameters: all manifest variables had loadings set at 0.7, with residual variance set at 0.51. The expected effect size of treatment on mediators and that of mediators on outcomes were all set to 0.30. The direct treatment effect on both outcomes was set at 0.10. Finally, residual variance for treatment was set to 0.5 and all auto-regressive paths at 0.5. Given these constraints, the expected effect size of mediation effects was as small as 0.09. Setting critical alpha at 0.05, and running 1000 Monte Carlo simulations, with a sample of 400 units, the estimated statistical power ranges from 0.85 to 0.95. Assuming a 20% drop-out (i.e. a sample size of N = 350) and letting all constraints invariant, the expected statistical power ranges from 0.77 to 0.89.

Procedure

A group of 150 adults (educators, psychologists, and teachers) participated in a three-day intensive training course plus a 28-lesson online multimedia training to introduce mindfulness in the classroom. The training course included elements of classroom mindfulness theory and practice, and basic information on neuroscience, psychology, socio-emotional skills, and ecological empathy. Only 22 Gaia trainers belonging to 11 schools were available to participate in the study. Twenty-eight classes (on average about three classes for each school), led by teachers who were trained to be Gaia instructors, were randomized into the mindfulness or control conditions.

The research design considers a treatment factor with two independent and randomly assigned conditions: Gaia training (i.e., experimental group) and Waiting list (i.e., control group). The experimental group included 210 students (58% of the sample). The students in the control group (N = 151, 42% of the sample) were allocated to the waitlist condition and attended usual classes during the intervention. After obtaining parents’ consent, all students received information about the general aims of the study and the program was conducted during classroom lessons. In the present study, the blinding of outcome assessors to intervention allocation was not possible. However, both teachers and outcome assessors were blind to the results of the scales.

The Gaia program

The Gaia Program is a mindfulness-based intervention that includes twelve one-hour weekly sessions and four modules (each module requires three work sessions): (1) motivation to participate in Gaia; (2) body self-awareness; (3) emotional self-awareness and empathy; (4) global and ecological self-awareness (for a detailed description of activities included in the Gaia program, see Ghiroldi et al., 2020). In this study, the original format was tailored for adolescents, by adapting the language and the modalities to increase their motivation to participate in the activities. Overall, participants were invited to shift attention firstly to the breath, then to body sensations, and later to focus on possible body tensions, identifying the associated emotions. At the end of each session, participants were invited to refocus on their breathing and the body as a whole. The proposed activities encompassed body scan, observation and description of body sensations and tensions, empowerment exercise to affirm one’s identity (saying to the group one’s name after a grounding exercise), relaxing and activating exercises that stimulated parasympathetic and sympathetic systems, respectively. Body movements, such as walking or exercising, were always accompanied by the invitation to mindful breathing. All sessions were preceded by group activities to facilitate the mindful experience and they were followed by a group sharing about the individual insights.

Measures

All participants completed measures at baseline, post-treatment, and 3-months follow up. Psychological well-being was assessed with the 18-item validated Italian version of the Psychological Well-Being (Sirigatti et al., 2013). Items are rated on a six-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 6 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating higher eudaimonic well-being. Psychological distress was assessed with the validated Italian version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Iani et al., 2014). The questionnaire includes 14 items rated on a four-point scale (from 0 to 3), with higher scorer indicating higher psychological distress. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ; Balzarotti et al., 2010) was used to measure individual differences in emotion regulation strategies, i.e., cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. The questionnaire contains 10 items based on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). Sample items are “I control my emotions by changing the way I think about the situation I’m in” (cognitive reappraisal) and “I keep my emotions to myself” (expressive suppression).

For the assessment of reliability, we used the McDonald’s omega coefficient (McDonald, 1999), which is more suitable than the Cronbach’s α because it corrects the underestimation bias of α when the assumption of the tau-equivalent model is violated (Dunn et al., 2014). As reliability coefficient, omega coefficients values above 0.60 will be considered acceptable. In our study, omega coefficients for each scale at pre-test, post-test, and follow up were respectively: Cognitive Reappraisal, ωT0 = 0.84, ωT1 = 0.88, and ωT2 = 0.90; Expressive Suppression, ωT0 = 0.61, ωT1 = 0.65, and ωT2 = 0.74; Psychological Distress, ωT0 = 0.77, ωT1 = 0.84, and ωT2 = 0.85; Psychological Well-being, ωT0 = 0.80, ωT1 = 0.84, and ωT2 = 0.84.

Analytic strategy

To check baseline equivalence between intervention and control group, we carried out a series of ANOVAs with treatment effects as independent variable on each separated relevant measures taken at pre-test (i.e., Cognitive Reappraisal, Expressive Suppression, Psychological Well-Being, and Psychological distress). Skewness and kurtosis were calculated to check the normality of the data; moreover, to verify whether multivariate outliers may have affected the data, we performed a multivariate normality test for all the variables. We estimated fixed effects for Treatment while controlling for random effects due to school classes variation. All estimates were corrected for Satterthwaite’s method.

An intention-to-treat analysis was performed to assess the impact of missing values on treatment effectiveness. We conducted a series of mixed-effects ANOVA models using outcomes (Cognitive reappraisal, Expressive suppression, Psychological well-being, and Psychological distress) as dependent variables with dropout/non-dropout as between subjects factor (completers vs. non-completers), time as within subjects factor (pre-test and post-test), as well as their interaction.

Furthermore, we conducted an attrition analysis to assess whether measures collected at pre-test and post-test significantly predicted dropout at follow-up by using the lmer function in the lme4 package for R software. For testing attrition, we performed a multilevel logistic regression model regressing the binary dropout variable on main outcomes as well as sex, age, and time (pre-test and post-test). To address this issue, we used Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods. All chains were run with a “burn-in” period of 5,000 followed by 50,000 monitoring iterations (initial values provided using penalised quasi-likelihood linearization, PQL) in order to account for dependency between repeated observations. For this purpose, we used the runMLwiN function in the R2MLwiN package.

Finally, we performed a dual process simplex structure equation model (i.e., SEM; Goldsmith et al., 2018), assuming the emotion regulation strategies (i.e., Cognitive reappraisal and Expressive suppression) as independent and parallel mediators of the treatment effects on Psychological well-being and Distress. We controlled for contemporaneous confounding variables (i.e., sex and age) between mediators and outcomes at baseline. To estimate the parameters, we used the Robust Maximum Likelihood Method of Estimation and the Robust Huber-White standard error estimates. Indirect effects were calculated using Montecarlo 95% C.I. estimates with 50,000 draws. Missing values were imputed using the Full Information Likelihood Approach, considering all available data for each case (Rosseel, 2012). Finally, we used item parcels to reduce random error and parameters estimate bias, and to improve model fit estimates (e.g., Hau & Marsh, 2004). For evaluating model’s goodness of fit, we considered the cutoff guidelines developed by Hu and Bentler (1999) and revised by Marsh et al. (2004). In particular, we reported the following fit indices and cutoffs: RMSEA, and SRMR values below 0.08, and CFI and NNFI above 0.90. As pointed out by Marsh et al. (2004), it is worth noting that these fit indices are sensitive to missing values (Davey et al., 2005) and to model complexity (Kenny & McCoach, 2003); thus, departure from cutoffs are not indicative of whether a model is valid or not (Marsh et al., 2004).

All analyses were run with R Software. SEM parameters were estimated with lavaan 0.6–12 (Rosseel, 2012), while Montecarlo estimates of indirect effects were calculated using semTools Package 0.5-6 (Jorgensen et al., 2022).

Results

Table 1 shows means and standard deviations of outcome measures at baseline, post-test, and follow-up. Results shows that two groups did not differ in psychological characteristics as measured at baseline, respectively Cognitive reappraisal (F[1, 21.62] = 1.42, p = .246), Expressive suppression (F[1, 19.19] = 0.02, p = .881), Psychological well-being (F[1, 28.36] = 3.01, p = .093), Psychological distress (F[1, 21.42] = 0.68, p = .417).

Intention-to-treat

Between pre- and post-treatment, the mortality rate was zero, whereas between post-test and follow-up there was a mortality rate of 52.9% (n = 102). At follow-up the sample consisted of 170 participants, of which 52.3% (n = 79) in the waiting list condition and 43.3% (n = 91) in the Gaia program. Missing values were approximately equally distributed between the two treatment conditions (χ2 = 2.50, p = .114). Intention-to-treat analyses showed no significant differences between completers and non-completers in all measures (Table 2).

Attrition analysis

The results of attrition analysis showed that none of the main outcomes or sex, age, and time predicted dropout at follow-up (Table 3). Thus, the dropout at follow-up was not explained by a specific pattern of outcomes score at the pre-test or at the post-test.

Testing mediation hypothesis

Fit indices for the model (Robust χ2(742) = 1177.32, p <.001) were satisfactory concerning absolute fit indices (Robust RMSEA = 0.047; 90% RMSEA C.I.: 0.040; 0.053; SRMR = 0.092), and approximately satisfactory concerning relative fit indices (Robust CFI = 0.908; TLI = 0.894; χ2/df = 1.59). As previously stated, it is likely that the missing values, and most of all, the model complexity (i.e., the number of manifest variables needed to define all latent constructs; Marsh et al., 2004; Kenny & McCoach, 2003) contributed to lower CFI and TLI. Considering the inconsistent literature on model’s goodness of fit (Marsh et al. 2004), we believe that, overall, even if these fit indices point to a partially satisfactory global fit, they do not undermine the validity of hypotheses we tested. Figure 1 shows direct effects between study variables included in the mediation model. For convenience, we report only significant completely standardized coefficients; for a thorough list of results, see table S1 in supplementary materials. Concerning hypotheses H1 and H2, no direct effects of the Gaia program were observed on expressive suppression, neither at post-test nor at follow-up; however, expressive suppression affected psychological distress at both post-treatment (β = 0.12), and at follow up (β = 0.23). Expressive suppression also showed a significant negative effect on psychological well-being at post-test (β = -0.12), and at follow up (β = -0.18). Concerning hypotheses H3 and H4, we found that the Gaia program effectively increased cognitive reappraisal at follow-up (β = 0.13) but not at post-treatment; and that cognitive reappraisal at post-test and at follow-up, positively affected psychological well-being (respectively: post-test, β = 0.20 and follow up, β = 0.20). Cognitive reappraisal also significantly decreased psychological distress at post-test (β = -0.20) but not at follow-up (β = -0.09). Finally, when considering the indirect effects (table S2) of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression on both psychological distress and well-being, the treatment had a positive and significant indirect effect on psychological well-being only via cognitive reappraisal, both measured at follow-up [β = 0.18, 95% C.I. (0.012; 0.395)].

Dual process simplex model with contemporaneous paths and contemporaneous residual covariance paths (Goldsmith et al., 2018, pp. 196) assuming Cognitive Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression as independent and parallel mediators (at T1 and T2, respectively post-test and follow-up) of the effect of Treatment (at T0, pre-test) on HADS and PWB (at T1 and T2, respectively post-test and follow-up). Note. Only latent structural relationships are shown. Values in path model represent completely standardized coefficients. TREATMENT = Control group (coded as 0) and Intervention group (coded as 1); HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; PWB = Psychological Well-Being.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to understand how a mindfulness school-based intervention (i.e., the Gaia program) exerted its effects on adolescents’ psychological distress and well-being. We hypothesized that two emotion regulation strategies, that is cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression, may be relevant processes. Overall, the results showed that only psychological well-being, but not psychological distress, may be explained by emotion regulation as a result of participating to the Gaia program. Specifically, only cognitive reappraisal, as measured at 3-months follow up, mediated the relationship between treatment and psychological well-being (supporting hypothesis 3); treatment-related changes in cognitive reappraisal accounted for a reduction of psychological distress at post-treatment, but not at follow up (partly supporting hypothesis 4); finally, while the use of expressive suppression was not sensitive to the Gaia program, suppression affected psychological distress (partly supporting hypothesis 1) and well-being (rejecting hypothesis 2).

These results suggest that youth participating to the Gaia program achieved higher levels of psychological well-being over time by using more frequently cognitive reappraisal to regulate their emotions. This is consistent with previous theoretical and empirical research suggesting that cognitive reappraisal is a relevant process when considering dispositional mindfulness and mindfulness-based interventions. Garland et al. (2015a) proposed that mindfulness can be considered a mental state that promotes cognitive reappraisal which, in turn, can generate eudaimonic well-being (Garland et al., 2015a). Mindfulness may generate a metacognitive state of awareness, which leads one to decenter from stress appraisals and broadens attention to novel information. As a consequence, it accommodates reappraisal of life circumstances that may lead, in turn, to higher levels of savoring positive aspects of the social context, higher motivations for values-driven behaviors, and a more meaningful and eudaimonic existence (Garland et al., 2015b). Likewise, mindfulness may be considered as an attentional process which may promote greater flexibility in generating new evaluations of emotional experience (Farb et al., 2014). Thus, our result suggests that the Gaia program may increase psychological well-being by allowing adolescents to decenter from stress appraisals into a metacognitive state of awareness, that is a step towards broadened attention to contextual information which facilitates reappraisal of life circumstances. It is worth noting that cognitive reappraisal at follow-up, but not at post-treatment, explained the effect of the Gaia program on psychological well-being. This result may suggest that reappraisal may require more time to change after the Gaia program in order to increase psychological well-being. Although reappraisal and well-being resulted both simultaneously affected by the intervention at the follow-up, we may not exclude that they could occur in a different time span. It may be possible that cognitive reappraisal changed in between the post-test and the follow-up (3 months), before affecting well-being at the follow-up.

Our results showed that the Gaia program increased the use of cognitive reappraisal, which in turn decreased the levels of psychological distress at post-treatment, but not at follow-up (partly supporting hypothesis 4). Mediation analysis revealed a non-significant indirect effect. Thus, improvements of psychological well-being, but not distress, could be accounted for by the increase of cognitive reappraisal. This is in line with previous findings showing that reappraisal was differentially associated with psychological well-being and distress, with weaker or null associations with psychopathology (e.g., anxiety and depression; Aldao et al., 2010; Kraiss et al., 2020). Thus, the Gaia program may foster the use of cognitive reappraisal, which is more beneficial to adolescents’ psychological well-being than distress. Indeed, well-being cannot be merely considered as the opposite of distress (Fava & Guidi, 2020).

Contrary to our expectations, findings suggest that expressive suppression does not represent a mechanism explaining the effects of the Gaia program on psychological distress. Specifically, the Gaia program did not show any effect on the use of expressive suppression; nevertheless, a heightened use of expressive suppression led to higher psychological distress (partly supporting hypothesis 1) and to lower psychological well-being (rejecting hypothesis 2). Drawing upon previous neuroscientific research, this result may be explained in light of mindfulness effects on the use of top-down (i.e., cognitive reappraisal) and bottom-up (i.e., expressive suppression) processing strategies (Chiesa et al., 2013; Guendelman et al., 2017). Neuroscientific evidence examined the hypothesis that mindful emotion regulation may lead to an increase in the activity of prefrontal cortex, which is relevant for cognitive control, and to a downregulation in the affect processing brain regions (e.g., amygdala; Tang et al., 2015). In this vein, the level of expertise may be the most important aspect. Indeed, in their systematic review, Tang et al. (2015) showed that novice meditators reported an increase in prefrontal activity following mindfulness, whereas experienced meditators did not use this prefrontal control (Tang et al., 2015). The authors concluded that expert meditators “might have automated an accepting stance towards their experience and thus no longer engage in top-down control efforts but instead show enhanced bottom-up processing” (Tang et al., 2015; p. 218). Accordingly, it is possible that the Gaia program, which focuses on the role of sensations, impulses, and body movements in self-disclosure, may improve top-down processes in novice meditators. Indeed, it was developed as a health promotion program targeting the general population in the school contexts, for participants with no previous experience of meditation intervention. It could be hypothesized that a longer and advanced practice within the frame of the psychosomatic mindfulness training could, instead, improve bottom-up processes (e.g., expressive suppression). Further research should address this question.

The finding that expressive suppression did not mediate any association between mindfulness intervention and psychological outcomes deserves a further explanation. Data on the relationship between mindfulness and expressive suppression is somewhat controversial. In a recent meta-analytic study in adults, mindfulness had no significant relationship with expressive suppression, whereas the association between mindfulness and cognitive reappraisal was confirmed (Zhou et al., 2023). Conversely, two cross-sectional studies with adolescents showed that expressive suppression, but not cognitive reappraisal, mediated the association between dispositional mindfulness and psychological distress (Ma & Fang, 2019; Pepping et al., 2016). Contrary to cognitive reappraisal, which is known as an “antecedent-focused” strategy since it begins before the emotion response is fully activated, expressive suppression is considered as a “response-focused” strategy, which occurs to modify the behavioral component of the emotional response (Gross, 2014). Previous theoretical and empirical studies reported that different aspects could hinder the change of expressive suppression during adolescence (e.g., Gross & Cassidy, 2019). For example, peers could encourage the tendency to suppress emotions; indeed, youths expected more negative interpersonal consequences than adults when disclosing their emotions; hence, peers reinforce expressive suppression to respect specific interpersonal norms, which may encourage the fear of interpersonal consequences of emotional disclosure, that is experienced as a vulnerability (e.g., Gardner et al., 2017). It is likely that participants in the Gaia program may not have benefited from mindfulness meditation due to interpersonal factors, such as social norms of the school context, which could impact on the role of mindfulness in improving expressive suppression. As a competing explanation, adolescents who learned to accept the emotional experience through the Gaia program, could also choose to not express an emotion immediately, since it could be seen as transitory and changeable, not tied to the present moment. This explanation is based on the distinction between the suppression of experience and the suppression of expression, where the latter has been conceptualized as not per se incompatible with mindfulness (Nyklíček, 2011). Thus, future studies may benefit from considering both expressive and experience suppression to detect potential differential associations with mindfulness.

Finally, we found no direct effects of the Gaia program on psychological distress, but positive significant effects on psychological well-being, as both measured at post-test. The MBIs effects on adolescents’ psychological distress are still controversial (e.g., Zhang et al., 2022). For example, MBIs significantly improved psychological distress in participants with mixed mental disorders and these gains were enhanced at 3-months follow-up (Tan & Martin, 2015). In another study, mindfulness has shown to be effective in reducing depressive symptoms at 6-months follow-up (Raes et al., 2014). Conversely, recent meta-analytic studies (Phillips & Mychailyszyn, 2022; Zhang et al., 2022) found small significant effect size for MBIs for both anxious and depressive symptoms, and psychological distress, suggesting that mindfulness meditation may not provide additional benefits for these internalizing symptoms when compared to active control groups or waitlist control groups. Our findings may suggest that the Gaia program is ineffective in reducing psychological distress. It is worth considering, however, that we can’t rule out possible delayed effects of the intervention, which couldn’t be examined in the current study. Our analysis based on two-time points may indeed be insufficient to detect a significant effect of the Gaia program on psychological distress. In a similar vein, a possible explanation may be that improvements in psychological distress (i.e., anxiety and depression) may first require improvements in eudaimonic well-being in youths; thus, a possible reduction in psychological distress at a later time point couldn’t be detected in the current study. Hallam and colleagues (2014) focused on the prospective relationship between eudaimonic values, anxious-depressive symptoms, and emotion regulation, reporting that eudaimonic values development in adolescence may indirectly reduce risk for anxious-depressive symptoms in young adulthood. In the latter, this trajectory was mediated by a process of promoting emotional competence (i.e., a greater sense of responsibility, self-control, planfulness, and autonomy) across emerging adulthood (Hallam et al., 2014). Future studies may consider to have more than two measurements of psychological distress.

Limitations and future research

Some evident limitations can be underlined. First, we did not include an active control group which would have reduced the risk of the Hawthorne effect. Second, we considered only three-points of measurement; it would have been more appropriate to have at least 4-points of measurements to verify our speculations about the obtained findings. However, it is worth noting that we could not provide for further assessments over time when the study was designed. Third, a high dropout rate was observed, especially at follow-up. However, it is worth noting that participants did not drop out of study; some schools, due to contextual factors, could not afford the completion of all follow-up measurements. Finally, we did not rule out the possible effects of the Gaia instructors on the mindfulness meditation and outcome measures. Future studies may control for the operator effect (e.g., frequency of meditation practice and level of experience in teaching) to avoid significant biases.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the current study provides new insights into the psychological mechanisms which mediated the relationship between mindfulness and positive and negative psychological outcomes among youth. Regarding the intervention, the program trained teachers who led the program and targeted a non-clinical population of adolescents in school contexts, who did not receive previous mindfulness interventions and, hence, novice to the practice. In addition, the program was based on a novel mindfulness intervention that integrated body-based practices, and was largely appreciated by teachers and students. Finally, the current study reviewed the existing studies which examined the emotional processes potentially implicated in the mindfulness effects over time. In particular, our findings pave the way for further studies to examine cognitive reappraisal as one of the main emotion regulation strategy implicated in the mindfulness meditation in the youth population.

Conclusions

Little is known about the effects of school-based mindfulness interventions on psychological distress. Moreover, no previous study examined these effects on psychological well-being and investigated emotion regulation as a potential process through mediation analysis. Thus, the present study sought to overcome these methodological and empirical gaps by examining the mediation role of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression on the relationship between a school-based mindfulness intervention and youths’ mental health (i.e., psychological distress and well-being).

Youths participating to a school-based mindfulness intervention, namely the Gaia program, experienced higher levels of psychological well-being, as reported in a previous study (Scafuto et al., 2024). Data of the present study suggest that this effect may be accounted for by increased use of cognitive reappraisal. Psychological distress at follow up was not sensitive to change. Expressive suppression did not mediate any association between the intervention and both psychological distress and well-being. These results suggest that cognitive reappraisal may be a relevant process, providing initial evidence that the mindfulness-to-meaning theory may be extended to youths and school contexts.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aldao, A., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2012). When are adaptive strategies most predictive of psychopathology? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121(1), 276–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023598

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004

Bach, J. M., & Guse, T. (2015). The effect of contemplation and meditation on ‘great compassion’ on the psychological well-being of adolescents. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(4), 359–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.965268

Balzarotti, S., John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2010). An Italian adaptation of the emotion regulation questionnaire. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26, 61–67. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000009

Chambers, R., Gullone, E., & Allen, N. B. (2009). Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(6), 560–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.06.005

Chiesa, A., Serretti, A., & Christian Jakobsenc, J. (2013). Mindfulness: Top– down or bottom–up emotion regulation strategy? Clinical Psychology Review, 33(1), 82–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.006

Cilar, L., Štiglic, G., Kmetec, S., Barr, O., & Pajnkihar, M. (2020). Effectiveness of school-based mental well-being interventions among adolescents: A systematic review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(8), 2023–2045. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14408

Clarke, D. M., & Currie, K. C. (2009). Depression, anxiety and their relationship with chronic diseases: A review of the epidemiology, risk and treatment evidence. Medical Journal of Australia, 190, S54–S60. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02471.x

Davey, A., Savla, J., & Luo, Z. (2005). Issues in Evaluating Model Fit With Missing Data. Structural Equation Modeling, 12(4), 578–597. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1204_4

De France, K., & Hollenstein, T. (2019). Emotion regulation and relations to well-being across the lifespan. Developmental Psychology, 55(8), 1768–1774. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000744

Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2014). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology, 105(3), 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12046

Dunning, D. L., Grifths, K., Kuyken, W., Crane, C., Foulkes, L., Parker, J., & Dalgleish, T. (2019). Research review: The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on cognition and mental health in children and adolescents - a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 60, 244–258. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12980

Farb, N. A., Anderson, A. K., Irving, J. A., & Segal, Z. V. (2014). Mindfulness interventions and emotion regulation. In Gross, J. J. (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation– Second Edition, pp. 548–568. Guilford Publications.

Fava, G. A., & Guidi, J. (2020). The pursuit of euthymia. World Psychiatry, 19(1), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20698

Fung, J., Kim, J. J., Jin, J., Chen, G., Bear, L., & Lau, A. S. (2019). A randomized trial evaluating school-based mindfulness intervention for ethnic minority youth: Exploring mediators and moderators of intervention effects. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-018-0425-7

Gardner, S. E., Betts, L. R., Stiller, J., & Coates, J. (2017). The role of emotion regulation for coping with school-based peer-victimisation in late childhood. Personality and Individual Differences, 107, 108–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.11.035

Garfinkel, S. N., & Critchley, H. D. (2013). Interoception, emotion, and brain: new insights link internal physiology to social behaviour. Commentary on: “Anterior insular cortex mediates bodily sensibility and social anxiety” by Terasawa et al. (2012). Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8(3), 231–234. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nss140

Garland, E. L., Gaylord, S. A., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2011). Positive reappraisal mediates the stress-reductive effects of mindfulness: An upward spiral process. Mindfulness, 2, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-011-0043-8

Garland, E. L., Farb, N. A., Goldin, P. R., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2015a). Mindfulness broadens awareness and builds eudaimonic meaning: A process model of mindful positive emotion regulation. Psychological Inquiry, 26, 293–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2015.1064294

Garland, E. L., Farb, N. A., Goldin, P. R., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2015b). The mindfulness-to-meaning theory: Extensions, applications, and challenges at the attention–appraisal–emotion interface. Psychological Inquiry, 26(4), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2015.1092493

Garland, E. L., Hanley, A. W., Goldin, P. R., & Gross, J. J. (2017). Testing the mindfulness-to-meaning theory: Evidence for mindful positive emotion regulation from a reanalysis of longitudinal data. PLoS ONE, 12, e0187727. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187727

Ghiroldi, S., Scafuto, F., Montecucco, N. F., Presaghi, F., & Iani, L. (2020). Effectiveness of a school-based mindfulness intervention on children’s internalizing and externalizing problems: The Gaia project. Mindfulness, 11(11), 2589–2603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01473-9

Goldsmith, K. A., MacKinnon, D. P., Chalder, T., White, P. D., Sharpe, M., & Pickles, A. (2018). Tutorial: The practical application of longitudinal structural equation mediation models in clinical trials. Psychological Methods, 23(2), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000154

Gross, J. J. (2014). Handbook of emotion regulation– (2nd ed.). Guilford Publications.

Gross, J. T., & Cassidy, J. (2019). Expressive suppression of negative emotions in children and adolescents: Theory, data, and a guide for future research. Developmental Psychology, 55(9), 1938. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000722

Guendelman, S., Medeiros, S., & Rampes, H. (2017). Mindfulness and Emotion Regulation: Insights from Neurobiological, Psychological, and Clinical Studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 220. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00220

Hallam, W. T., Olsson, C. A., O’Connor, M., Hawkins, M., Toumbourou, J. W., Bowes, G., & Sanson, A. (2014). Association Between Adolescent Eudaimonic Behaviours and Emotional Competence in Young Adulthood. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 1165–1177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9469-0

Hau, K. T., & Marsh, H. W. (2004). The use of item parcels in structural equation modelling: Non-normal data and small sample sizes. British Journal of Math, Statistics, and Psychology, 57(2), 327–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.2004.tb00142.x

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Huppert, F. A., & Johnson, D. M. (2010). A controlled trial of mindfulness training in schools: The importance of practice for an impact on well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(4), 264–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439761003794148

Iani, L., Lauriola, M., & Costantini, M. (2014). A confirmatory bifactor analysis of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in an Italian community sample. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12, 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-12-84

Jorgensen, T. D., Pornprasertmanit, S., Schoemann, A. M., & Rosseel, Y. (2022). semTools: Useful tools for structural equation modeling. R package version 0.5–6. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=semTools

Kenny, D. A., & McCoach, D. B. (2003). Effect of the Number of Variables on Measures of Fit in Structural Equation Modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 10(3), 333–351. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM1003_1

Klingbeil, D. A., Renshaw, T. L., Willenbrink, J. B., Copek, R. A., Chan, K. T., Haddock, A., Yassine, J., & Clifton, J. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions with youth: A comprehensive meta-analysis of group-design studies. Journal of School Psychology, 63, 77–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2017.03.006

Kraiss, J. T., Ten Klooster, P. M., Moskowitz, J. T., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2020). The relationship between emotion regulation and well-being in patients with mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 102, 152189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152189

Ma, Y., & Fang, S. (2019). Adolescents’ mindfulness and psychological distress: The mediating role of emotion regulation. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1358. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01358

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., & Wen, Z. (2004). In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling, 11(3), 320–341. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2

McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment. Erlbaum.

Nani, A., Manuello, J., Mancuso, L., Liloia, D., Costa, T., & Cauda, F. (2019). The Neural Correlates of Consciousness and Attention: Two Sister Processes of the Brain. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13, 1169. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.01169

Nyklíček, I. (2011). Mindfulness, emotion regulation, and well-being. In Nyklíček, I., Vingerhoets, A., Zeelenberg, M. (Eds.), Emotion regulation and well-being, pp. 101–118. Springer.

Pepping, C. A., Duvenage, M., Cronin, T. J., & Lyons, A. (2016). Adolescent mindfulness and psychopathology: The role of emotion regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 99, 302–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.04.089

Phillips, S., & Mychailyszyn, M. (2022). The effect of school-based mindfulness interventions on anxious and depressive symptoms: A meta-analysis. School Mental Health, 14, 455–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-021-09492-0

Price, C. J., & Hooven, C. (2018). Interoceptive awareness skills for emotion regulation: Theory and approach of mindful awareness in body-oriented therapy (MABT). Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 798. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00798

Raes, F., Griffith, J. W., Van der Gucht, K., & Williams, J. M. G. (2014). School-based prevention and reduction of depression in adolescents: A cluster-randomized controlled trial of a mindfulness group program. Mindfulness, 5, 477–486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0202-1

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Ruini, C., Ottolini, F., Tomba, E., Belaise, C., Albieri, E., Visani, D., Offidani, E., Caffo, E., & Fava, G. A. (2009). School intervention for promoting psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 40(4), 522–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.07.002

Scafuto, F. (2021). Individual and social‐psychological factors to explain climate change efficacy: The role of mindfulness, sense of global community, and egalitarianism. Journal of Community Psychology, 49(6), 2003–2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22576

Scafuto, F., Ghiroldi, S., Montecucco, N. F., Presaghi, F., & Iani, L. (2022). The Mindfulness-based Gaia program reduces internalizing problems in high-school adolescents: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness, 13(7), 1804–1815. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01920-9

Scafuto, F., Ghiroldi, S., Montecucco, N. F., De Vincenzo, F., Quinto, R. M., Presaghi, F., & Iani, L. (2024). Promoting well‐being in early adolescents through mindfulness: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Journal of Adolescence, 96(1), 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12252

Schäfer, J. Ö., Naumann, E., Holmes, E. A., Tuschen-Caffier, B., & Samson, A. C. (2017). Emotion regulation strategies in depressive and anxiety symptoms in youth: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 261–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0585-0

Seligman, M. E., Ernst, R. M., Gillham, J., Reivich, K., & Linkins, M. (2009). Positive education: Positive psychology and classroom interventions. Oxford Review of Education, 35(3), 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980902934563

Shapiro, S. L., Carlson, L. E., Astin, J. A., & Freedman, B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 373–386. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20237

Sirigatti, S., Penzo, I., Iani, L., Mazzeschi, A., Hatalskaja, H., Giannetti, E., & Stefanile, C. (2013). Measurement invariance of Ryff’s psychological well-being scales across Italian and Belarusian students. Social Indicators Research, 113(1), 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0082-0

Solmi, M., Radua, J., Olivola, M., Croce, E., Soardo, L., Salazar de Pablo, G., Shin, J., Kirkbride, J. B., Jones, P., Kim, J. Y., Carvalho, A. F., Seeman, M. V., Correll, C. U., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2022). Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Molecular Psychiatry, 27(1), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7

Tan, L., & Martin, G. (2015). Taming the adolescent mind: A randomised controlled trial examining clinical efficacy of an adolescent mindfulness-based group programme. Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 20(1), 49–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12057

Tan, Y., Wang, X., Blain, S. D., Jia, L., & Qiu, J. (2023). Interoceptive attention facilitates emotion regulation strategy use. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 23(1), 100336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2022.100336

Tang, Y. Y., Hölzel, B. K., & Posner, M. I. (2015). The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 16(4), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3916

Taylor, A. G., Goehler, L. E., Galper, D. I., Innes, K. E., & Bourguignon, C. (2010). Top-Down and Bottom-Up Mechanisms in Mind-Body Medicine: Development of an Integrative Framework for Psychophysiological Research. Explore, 6(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2009.10.004

Tudor, K., Maloney, S., Raja, A., Baer, R., Blakemore, S. J., Byford, S., Crane, C., Dalgleish, T., De Wilde, K., Ford, T., Greenberg, M., Hinze, V., Lord, L., Radley, L., Opaleye, E. S., Taylor, L., Ukoumunne, O. C., Viner, R., MYRIAD Team, Kuyken, W., & Montero-Marin, J. (2022). Universal Mindfulness Training in Schools for Adolescents: a Scoping Review and Conceptual Model of Moderators, Mediators, and Implementation Factors. Prevention Science, 23(6), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-022-01361-9

van Lissa, C. J. (2022). Mapping phenomena relevant to adolescent emotion regulation: A text-mining systematic review. Adolescent Research Review, 7(1), 127–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-021-00160-7

Verzeletti, C., Zammuner, V. L., Galli, C., & Agnoli, S. (2016). Emotion regulation strategies and psychosocial well-being in adolescence. Cogent Psychology, 3(1), 1199294. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2016.1199294

Wang, Y. A., & Rhemtulla, M. (2021). Power analysis for parameter estimation in structural equation modeling: A discussion and tutorial. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 4(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245920918253

Zhang, Y., Chen, S., Wu, H., & Guo, C. (2022). Effect of Mindfulness on Psychological Distress and Well-being of Children and Adolescents: A Meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 13(2), 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01775-6

Zhou, S., Wu, Y., & Xu, X. (2023). Linking Cognitive Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression to Mindfulness: A Three-Level Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1241. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20021241

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the teachers who administered the questionnaires and delivered the intervention. We also thank the Headmasters and all school communities to allow data collection.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. Partial financial support was received from the Italian Ministry of Labour and Social Policies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: FS, SG, NFM, and LI; Methodology: FP; Formal analysis and investigation: FP; Writing - original draft preparation: FDV and RMQ; Writing - review and editing: FS and FP.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the ethical review board for psychological research of the European University of Rome (007a/2018).

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the parents of the adolescents included in the study.

Financial interests

The authors declare they have no financial interests.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Scafuto, F., Quinto, R.M., Ghiroldi, S. et al. The mediation role of emotion regulation strategies on the relationship between mindfulness effects, psychological well-being and distress among youths: findings from a randomized controlled trial. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06081-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06081-7