Abstract

Destructive leadership, a prevalent negative behavior in modern organizations, continues to captivate the interest of scholars and professionals due to its detrimental aftermath. Drawing from social psychological (culture) and conservation of resources theory, we explore the moderating impact of psychological power distance on the link between destructive leadership and emotional exhaustion. The main contribution of this study is that it has created new information about the moderating role of some specific sub-dimensions of psychological power distance (e.g., hierarchy, prestige) in the relationship between destructive leadership and emotional exhaustion. Our findings also reveal a positive correlation between a destructive leadership style and emotional exhaustion. Furthermore, the prestige aspect of psychological power distance amplifies the influence of deficient leadership abilities and unethical conduct on emotional exhaustion. Notably, our study highlights that in the Turkish context, characterized by high power distance, and escalating hierarchies the impact of nepotism disparities on emotional exhaustion. In conclusion, these novel insights underscore a significant research avenue regarding cultural facets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The actions of leaders in charge of societies and organizations have far-reaching effects, influencing organizational culture and the mental well-being of employees. On the other hand, culture is also recognized to influence various organizational relationships. Concordantly, one cultural element that can explain variations in leadership effectiveness, work attitudes, or job performance is an employee’s power distance orientation (Leonidou et al., 2021; Matta et al., 2022). Power distance at an individual level also serves as a moderating factor on various aspects, such as the effectiveness of leadership, employees’ perceptions and opinions of their organizations, and the core impacts of HR practices on employees (e.g., Adamovic, 2023; Li et al., 2017; Loi et al., 2012). In this context, despite some recent studies exploring the nature of power and its effects on leader behavior and employee responses from a psychological standpoint (e.g., Kelemen et al., 2020; Liao et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2021), given the extensive influence of psychological power, it is challenging to assert that the literature has fully developed.

According to the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, resources are broadly defined as objects, personal characteristics, conditions, or energies that are valued because they help one to either directly obtain his or her goals or thwart his or her goal-relevant tendencies (Hobfoll, 2011). However, some non-constructive leadership behaviors such as DL continue to threaten the motivation level of employees (Rasid et al., 2013), individual resources (Hobfoll, 2011), and the welfare of organizations (Brouwers & Paltu, 2020; Veldsman, 2012). This fact creates a need to understand the contextual development of DL in organizations. DL can be seen as a new type of leadership where leaders engage in systematic and prolonged psychological abuse of subordinates (Ryan et al., 2021). Previous research has indicated that the impact of DL may depend on the context, as relationships can vary based on cultural and situational factors (e.g., Burns, 2021; Fors Brandebo, 2020). In parallel, numerous studies reveal the consequences of such leadership styles (Tepper, 2000) and propose theoretical models explaining the mechanisms of these styles (Einarsen et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2010). More specifically, negative leadership styles have been associated in the current literature with Emotional Exhaustion (EE) (Gkorezis et al., 2015; Koç et al., 2022), turnover intentions (Badar et al., 2023), and counterproductive work behavior (Murad et al., 2021). Besides, there is also an increasing research trend regarding the roles played by leadership in the moods and emotions of subordinates (Bono et al., 2007; Gooty et al., 2010).

“National culture has a crucial role in influencing the occurrence of leadership style” (Zhang & Liao, 2015, p. 960), and shapes subordinates’ reactions toward these leadership styles (Hofstede, 2001; Tepper et al., 2017). One of these leadership styles is Destructive Leadership (DL) which is increasing in today’s societal and business areas (Krasikova et al., 2013) and prevents proper organizational functioning (Cascio & Aguinis, 2008). Organizations invest substantial resources in safeguarding and enhancing employee well-being (Salas-Vallina et al., 2021). Within this framework, COR, rooted in the resource-based perspectives of organizations, underscores individuals’ endeavors to safeguard, uphold, and cultivate their resources, highlighting bad management and stress as perceived threats to these resources (Hobfoll, 2011). Therefore, based on the COR, enhancing our understanding of the phenomenon of DL by exploring the impact of Psychological Power Distance (PPD) experienced by subordinates on their perceptions of leaders’ abusive behaviors is also significant in terms of decreasing employees’ level of Emotional Exhaustion (EE). EE, is expressed as “feelings of being emotionally drained by one’s work” (Bakker & Costa, 2014, p. 2), and one of the primary emotional states experienced by employees today. In conclusion, the COR theory as a factor in work-related stress and destructive leadership can be used as a basis to eradicate the harmful effects of destructive leadership for the betterment of professional environments.

As a cultural factor, “Power Distance” (PD) assesses the probability that individuals facing greater inequality within the same social framework will recognize and expect unequal power distribution (Gonzalez, 2021). Hence, PD is a distinguishing feature among societies (Meydan et al., 2014). In this line, the PD beliefs of subordinates also vary depending on different leadership styles (Yang, 2020). For instance, in some cultures, leaders garner respect for taking decisive action, while in others, collaborative and participative decision-making methods hold more significance (Ahmad et al., 2021, p. 1112). However, the issue of low reliability persists in many power distance scales (Taras, 2014). In this context, Adamovic (2023) contends that the measurement components of the Psychological Power Distance (PPD) scale he created amalgamate a broad power distance aspect and encompass noteworthy, though distinct, facets of power distance. Besides, although the concepts of hierarchy and power are often used as substitute concepts, the distinction between these two concepts has been significantly neglected in previous research (Aïssaoui & Fabian, 2015). For example, “in France, employees often do not tolerate power differences, but they tend to value a strong hierarchy” (Adamovic, 2023, p. 3; d’Iribarne, 1996).

However, empirical research on the effects of psychological power distance on DL and related outcomes such as employee EE is surprisingly scarce. This paper seeks to address this gap in the literature. Thus, we aim to explore the potential moderating impact of the newly defined PPD on the connection between DL and EE to achieve trustworthy empirical findings. On the other hand, the study specifically focuses on a sample of Turkish employees, given that Türkiye is the largest economy in the Middle East and Turkish cultural values have had a profound impact on the way organizations are managed in the Middle East region. Besides, most countries in the Middle East were founded with the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and are societies that come from the same traditions and customs (Lindholm, 2008). Thus, as a society that traditionally values respect and compliance with authority, Türkiye represents an ideal context to study the effects of psychological power distance.

Theoretical background

Destructive leadership

“Destructive leadership is conceptualized as a broad umbrella” (Mackey et al., 2021, p. 707) that ranges from abusive supervision (Tepper, 2000; Tepper et al., 2017) to overburdening followers (Schmid et al., 2019). Therefore, a wide variety of theories and different approaches, such as the Psychodynamic approach (Pillay & April, 2022) or Strain theory (Chen & Cheung, 2020) which is a criminological theory, have been used to explain the behaviors and effects of Destructive Leadership (DL). On the other hand, researchers have discovered that a rise in disruptive behaviors, which can deplete individuals’ psychological resources, may stem from factors like heightened anxiety (Byrne et al., 2014), work-related stress (Rosenstein, 2017), or excessive job pressure (Lam et al., 2017). Concurrently, the field of DL is experiencing increased diversity. Within this realm, DL manifests in various structural forms. As per Einarsen et al. (2007) and Larsson et al. (2012), these forms can be categorized as active or passive. Active behaviors encompass traits such as arrogance, unfairness, and intimidating or disciplining subordinates. Passive behavioral patterns highlight leader qualities like disinterest, avoidance of conflict, or poor planning skills (Larsson et al., 2012). Active behaviors are systematic and deliberate, while passive forms indicate deficiencies in leaders’ work and responsibilities (Einarsen et al., 2007). In addition, DL is divided into two dimensions in the literature: task and relationship. Task-related behaviors represent perceptions of the leader’s competence, including:

-

Isolation from outside interference and excessive control.

-

Lack of determination and uncertainty.

-

Stress and loss of control.

The relationship-related behaviors dimension refers to the leader’s skills in human relations, such as:

-

Low ability to relate to colleagues and subordinates and lack of job satisfaction.

-

Lack of understanding and self-centered behavior (Fors et al., 2016).

On the other hand, “employees will attribute leadership behavior in the process of interaction with the leaders” (Jiao & Wang, 2023, p. 2), and the psychological states of subordinates will also be affected depending on their attribution. As a result, based on attribution theory (Heider, 1958; Weiner, 1985), it should not be ignored that whether the above-mentioned behaviors will be perceived as destructive or non-destructive may differ depending on the psychological state and perceptions of the subordinates in addition to cultural impact (Kong & Jogaratnam, 2007; Ojo, 2012).

Emotional exhaustion

Burnout, a psychological syndrome brought on by a prolonged reaction to ongoing workplace stressors (Maslach et al., 2001), is a significant issue that is becoming worse as workers are subjected to increasing pressure and demands from their managers under different cultural contexts (Rattrie et al., 2020). Moreover, burnout has been associated with several negative organizational outcomes, including job performance, emotional labor, and reduced employee well-being (Moon & Hur, 2011; Qiu et al., 2023; Maslach et al., 2001). “It is generally accepted to encompass three dimensions that occur in a developmental sequence” (Strack et al., 2015, p. 578): from emotional exhaustion (EE) to depersonalization and subsequent decline in achievement (Cordes & Dougherty, 1993; Maslach et al., 2001). Within this framework, EE refers to the extent to which an individual is depleted or lacking in physical and psychological resources to cope with an interpersonal stress situation (Maslach et al., 2001). Employees who experience EE at work feel extremely stressed because they lose their physical and mental endurance (Obi et al., 2020) which ultimately leads to unhealthy tendencies as well as anxiety, stress, and depression (Bianchi et al., 2015; Weigl et al., 2017). On the other hand, the main characteristics of EE at the organizational level are the desire to quit work, absenteeism, and low morale (Maslach, 1996). Ultimately, the chronic experience of negative emotions in both individual and organizational contexts and the difficulties employees experience in regulating them can deplete their cognitive and emotional resources, which emerges as an important risk factor for EE (Chang, 2009; Hsieh et al., 2011).

Destructive leadership and emotional exhaustion

Different leadership styles have a known impact on employees’ emotions (Baig et al., 2021), and “employees’ perceptions about the leader are likely to affect their attitudes” (Gkorezis et al., 2015, p. 622). In this context, destructive leadership styles (e.g., abusive supervision, petty tyranny, negative leadership) may trigger negative emotional reactions from employees (Schilling & Schyns, 2015), and increase employees’ emotional exhaustion (Chi & Liang, 2013). According to the Emotional Dissonance theory, negative supervision may also lead employees to conceal their true emotions (Naseer & Raja, 2021). Thus, scholars are focusing on leaders’ negative behavioral impact on employees’ emotional exhaustion levels (Gkorezis et al., 2015) to increase employee well-being at work (Hetrick et al., 2022). In addition, interpersonal stressors that diminish the well-being of employees are frequently experienced within the organizational atmosphere dominated by DL due to the nature of this harmful style (Hetrick et al., 2022). According to the Emotional Dissonance theory, negative supervision may also lead employees to conceal their true emotions (Naseer & Raja, 2021). Within this framework, scholars are focusing on leaders’ negative behavioral impact on employees’ emotional exhaustion levels (Gkorezis et al., 2015) to increase employee well-being at work (Hetrick et al., 2022), interpersonal stressors that diminish the well-being of employees are frequently experienced within the organizational atmosphere dominated by DL due to the nature of this harmful style (Hetrick et al., 2022), this article bases the theoretical connection between Destructive Leadership (DL) and Emotional Exhaustion (EM) on the definition of Einarsen et al. (2007).

[..] is the systematic and repeated behavior of a leader or manager that harms the organization’s legitimate interests by undermining the organization’s resources, and effectiveness, motivation, and job satisfaction of subordinates (p. 208).

Current studies have explored the positive relationship between despotic, toxic, and destructive leadership with emotional exhaustion (e.g., Shahzad et al., 2023; Koç et al., 2022). In this context, “meta-analytic evidence demonstrates that DL has negative consequences for followers’ workplace behaviors (e.g., job performance, organizational citizenship behaviors [OCBs], workplace deviance)” (Mackey et al., 2019, p. 3). These empirical findings may suggest that DL outputs could also result in EM among employees. In conclusion, destructive leaders can cause fundamental problems in business life, such as increasing the level of emotional exhaustion (Krumov et al., 2016), and subordinates who are constantly exposed to leaders’ destructive practices experience frustration and emotional exhaustion (Glasø & Vie, 2009). Given the theoretical discussions above, the research’s first hypothesis was formulated as follows.

-

H1: There is a positive relationship between destructive leadership and emotional exhaustion.

Psychological power distance

The PPD concept originates from a multidisciplinary field of study called cross-cultural psychology, which seeks to understand how culture impacts the cognitive and behavioral outcomes of individuals and groups (Yang, 2020). According to Hofstede (1991, p. 27), “power distance can be described as the degree to which individuals who are less powerful within a country’s institutions and organizations anticipate and acknowledge the unequal distribution of power”. In this context, “Shore and Cross (2005, p. 57) underlined that power is distributed more equitably in low power distance cultures and unequally in high power distance cultures. For instance, the power distance index (Khakhar & Rammal, 2013) shows that the Arab world, which values traditional authority highly (Inglehart, 1997), scores highly in this index, and people working in these cultures strictly follow higher hierarchical orders (Chiaburu et al., 2015; Korkmazyurek & Korkmazyurek, 2023). In summary, “individuals who score highly on psychological power distance also tend 1) accept and tolerate power differences in the workplace, 2) avoid conflict with authority figures, 3) prefer a clear hierarchy at work, 4) strive for status and prestige, and 5) expect a social distance between managers and employees.” (Adamovic, 2023, p. 2).

Psychological power distance as a moderator

It has been suggested that various cultures have their norms regarding what constitutes good or bad leadership, and these norms may be reflected in the perception of psychological power distance (Tang et al., 2020). In this context, numerous studies explore the connection between PD and leaders’ influence tactics as PD decides if subordinates in a culture would accept a leader’s influence and the specific situations in which a leader might face resistance from a group of subordinates. Thus, investigating the role of PD in employees’ perception of leaders and better understanding the impact of leaders on employee well-being, will not only inform practices for workplace health intervention but also enlighten leadership researchers in discussing the universal and contingency theory of leadership. On the other hand, several power distance measures, like the ones created by Cable & Edwards (2004), Dorfman & Howell (1988), and Maznevski and colleagues (2002), have produced interesting findings on the importance of power distance concerning employee results and leadership (Adamovic, 2023, p. 2). As an example, Tepper (2007) claims that “countries with high power distance experience more abusive supervision”. Thus, individuals characterized by large power distance have a high tolerance for lack of autonomy and rely more on centralization and formalization of authority (Hofstede, 1980). In this context, PPD influences how people feel, think, and act about problems of status and power at work and is crucial in understanding how leaders and subordinates interact (Adamovic, 2023, p. 1).

The moderating impact of PD on the link between workers’ job satisfaction, performance, and absenteeism was highlighted by Lam and Friends (2002. p.14). On the other hand, Farh and Friends (2007: 721) found in their study that PD had a negative moderating effect on the relationship between work outcomes such as organizational commitment, job performance, and conscientiousness. According to the findings above, we can argue that PPD has a deterministic effect on the functioning of the theoretical mechanisms between DL and EM. Besides, In countries with high power distance, abuse by superiors is quite normative and consistent for subordinates in superior-subordinate relationships (Tepper, 2007). In this regard, the need for power in the prestige dimension (Carl et al., 2004; Hofstede, 2001; Schwartz, 2014), which is an organic extension of previous power distance studies, is also associated with narcissistic and Machiavellian actions and attitudes (Jonason et al., 2022). “People with high power distance orientation in the workplace typically accept status disparities, whereas people with low power distance orientation frequently support treating everyone equally regardless of status symbols.” (Adamovic, 2023, p. 3). Conversely, workers with a low power distance orientation favor participatory leadership and decision-making processes which is not as prevalent under abusive supervision (Rao & Pearce, 2016). As a result, in countries with low power distance, abusive supervision may affect the emotional state of subordinates (Meydan et al., 2014).

De Clercq and colleagues (2021) discovered that PPD is positively associated with subordinates’ perception of superiors’ destructive leadership. This indicates that when subordinates perceive high PPD, they are more likely to view their leaders as engaging in such destructive behaviors. This correlation can also be attributed to abusive supervision, a form of destructive leadership behavior. According to social learning theory (Rumjaun & Narod, 2020), when leaders’ power is internalized and reflected as subordinates’ psychological power distance, the aggressive behaviors displayed by leaders are likely to be observed and learned by subordinates. These aggressive behaviors could then lead to emotionally exhausting reactions in the subordinates. Correlationally, this study suggests that psychological power distance mediates the link between destructive leadership behaviors and subordinates’ emotional exhaustion levels.

-

H2: Psychological power distance has a moderating role in the relationship between perceived destructive leadership and emotional exhaustion.

Method

The causal research method which is one of the quantitative research methods is used in the study. Cross-sectional data were collected using an electronic survey form through the convenience sampling method. Participants received the link to the electronic survey form via social media and email. The statistical analyses were carried out with AMOS 24 and SPSS 27.

Sample and procedure

The survey sample size was determined by the Non-random convenience sampling method and the process of its determination was as follows: The sample size that can numerically represent the universe of working people was calculated with the formula below (Ding et al., 2022).

In this formula, n represents the required sample size and Z represents the z-statistic at a 90% confidence level (Z = 1.64). σ represents the standard deviation of the overall population and takes the value of 0.5. d is the tolerance error or sampling error. It is the difference between the universe parameter and the statistical value obtained from the sample. Since such a research model has not been studied before in the Turkish culture, the tolerance error for the sample was accepted as 10%. The final required sample size was calculated as 67.

Along this line, in a homogenous group with a reliability of 0.90 and a sampling error of 0.10, a sample group of 61 people can represent a universe of 100 million people (Yazıcıoğlu & Erdoğan, 2004). Moreover, in a heterogeneous group, a sample size of 96 is sufficient. Data were collected from a total of 222 employees working in different jobs by using the convenience sampling method via an online survey. This sample strategy allows us to collect data that covers more industries in Türkiye. The participation of participants in the research was voluntary. Working in a workplace was the only criterion for participants. In this context, it was accepted that the sample size was large enough to represent the universe.

117 (53%) of the participants were female, and 105 (47%) were male. The participants have 14.48 (sd = 10.46) mean years of working experience, while their age was between 19 and 67 years, with a mean value of 40.87 (sd = 9.42). % 24.9 of the participants were between 19 and 34, % 24.9 between 35 and 40, % 25.8 between 41 and 47, and % 24,4 between 47 and 67 years old.

Measure of psychological power distance

The PPD perception was measured with the scale, developed by Adamovic (2023). This scale is a five-point Likert-type scale (1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree) comprising fifteen items under five factors (Power, Conflict with Authority Figure, Hierarchy, Prestige, and Social Distance). Ascending numbers indicate the extent to which power distance was perceived. The overall original psychological power distance scale demonstrated strong reliability (α = 0.82). The scale has not been used in Turkish before. For this reason, firstly, this scale was adapted to Turkish, and then the validity and reliability of the scale were tested. By adopting this scale, the method suggested by Brislin et al. (1973) was used. This method includes five basic steps: translation into the target language, evaluation of the translation into the target language, back-translation into the source language, evaluation of the back-translation into the source language, and final evaluation with experts. After the adaptation process, exploratory factor analysis was applied for the validity of the scale. In the exploratory factor analysis, the Principal Axis Analysis method and the Varimax Rotation Technique were applied to calculate factor loadings. Factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were taken into consideration. As a result of the factor analysis, it was seen that all factor loadings were higher than 0.30 and there were no overlapping items. The lowest factor loading value recommended for a good factor analysis is 0.30 (Tavakol & Wetzel, 2020). As a result of the exploratory factor analysis, the KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) value was found to be 0.76, and the result of Bartlett’s test was found to be p < 0.001. After that, Confirmatory Factor Analysis was performed to examine the structural validity of the measurement tool. The single-factor, first-level related, unrelated, and second-level related models were tested and Psychological Power Distance Scale showed the highest goodness of fit in the first-level related model (Δχ2 = 145.18, p < 0.001, SD = 79, Δχ2/SD = 1.84, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.92, IFI = 0.92, TLI = 0,90) which verified it’s original five-factor dimension. In our study, the Psychological Power Distance scale showed generally strong reliability (α = 0.78).

Measurement of destructive leadership

Destructive Leadership was measured with the scale which was developed by Aydinay (2022). Five Point Likert-type scale (1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree) comprises 26 items under five factors (Inadequate leadership skills and unethical behaviors, Authoritarian leadership, Inability to deal with new technology and other changes, Nepotism (favoritism), Callousness toward subordinates). Ascending numbers indicate the extent to which destructive leadership was perceived. The original scale’s reliability was reported using Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of α = 0.97, which showed that the scale was reliable. The validity of the scale was tested with confirmatory factor analysis, (Δχ2 = 590.23, p < 0.01, SD = 280, Δχ2/SD = 2.11, RMSEA = 0.07, CFI = 0.94, IFI = 0.94, TLI = 0,93) which verified it’s original five-factor dimension. In our study, the Destructive Leadership scale showed generally strong reliability (α = 0.97).

Measurement of emotional exhaustion

In the study, to measure the emotional exhaustion levels the emotional exhaustion dimension scale in the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MTE) (Maslach et al. 1996), translated into Turkish by Ergin (1992), was used. Five-point Likert-type scale (1 strongly disagree to 5 strongly agree) comprises 9 items under one factor. The original scale’s reliability was reported using Cronbach’s coefficient alpha of α = 0.86, which showed that the scale was reliable. The validity of the scale was tested with confirmatory factor analysis, (Δχ2 = 40.51, p < 0.006, SD = 21, Δχ2/SD = 1.93, RMSEA = 0.07, GFI = 0.96, CFI = 0.98, IFI = 0.98, TLI = 0,97) which verified it’s original one-factor dimension. In our study, the Emotional Exhaustion scale showed generally strong reliability (α = 0.91).

Results

Table 1 displays the variables’ descriptive statistics as well as the Pearson correlation coefficients. Examining the correlations between the variables of the study, all sub-dimensions of Destructive Leadership [Inadequate leadership skills and unethical behaviors (r = 0.46, p < 0.01), Authoritarian leadership (r = 0.49, p < 0.01), Inability to deal with new technology and other changes (r = 0.42, p < 0.01), Nepotism (r = 0.40, p < 0.01), Callousness toward subordinates (r = 0.40, p < 0.01)] were positively correlated with emotional exhaustion. There was no correlation between Psychological Power Distance sub-dimensions (Power, Conflict with Authority Figures, Hierarchy, Prestige, and Social Distance) and emotional exhaustion. Moreover, there was no correlation found between sub-dimensions of Destructive Leadership and Psychological Power Distance.

Using SPSS 27 software, a multiple regression analysis was executed to test the research’s first hypothesis. First of all, by controlling the effects of gender and age, the direct relationship between destructive leadership dimensions and emotional exhaustion was examined. Table 2 displays the analysis findings. The variance explained by emotional exhaustion in this model is R2 = 0.31. The results indicate that Authoritarian leadership (b = 0.29, p < 0.01) is positively and significantly associated with emotional exhaustion. The study’s first hypothesis is supported by this result. The other sub-dimensions of Destructive leadership (Inadequate leadership skills and unethical behaviors, Inability to deal with new technology and other changes, Nepotism, and Callousness toward subordinates) aren’t associated with emotional exhaustion (p > 0.05).

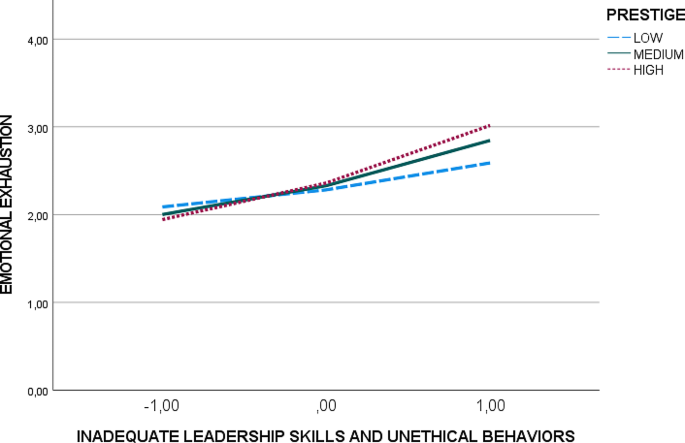

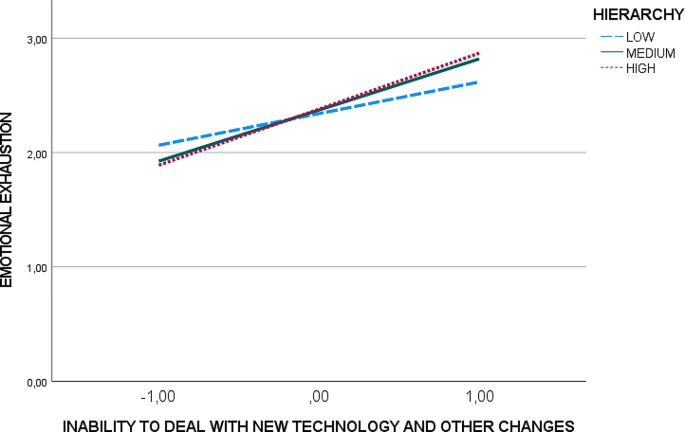

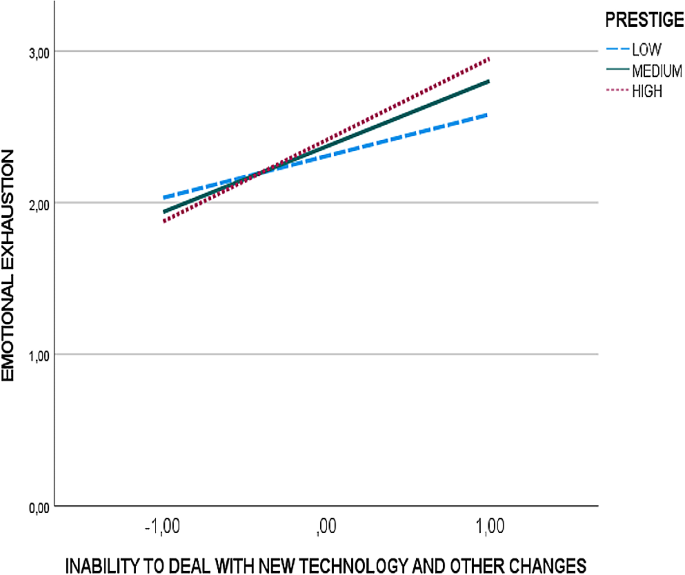

Next, to test hypothesis 2, the moderating effect of psychological power distance sub-dimensions in the relationship between destructive leadership sub-dimensions and emotional exhaustion was examined through SPSS PROCESS 4.1 macro (Hayes, 2018). Totally twenty-five regression analyses were conducted. Model 1 of the PROCESS was applied in all analyses, based on 5000 bootstrap samples. As a result of all analyses, it was found that the Inadequate Leadership Skills and Unethical Behaviors X Prestige interaction variable (b = 0.17, 0.05 < 95% CI < 0.28), the Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes X Hierarchy interaction variable (b = 0,13, 0.02 < 95% CI < 0.24), the Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes X Prestige interaction variable (b = 0.16, 0.05 < 95% CI < 0.27), Nepotism X Hierarchy interaction variable (b = 0.10, 0.009 < 95% CI < 0.20) was significantly and positively associated with emotional exhaustion. All the other interactions were not significant.

To understand the interaction of Inadequate Leadership Skills and Unethical Behaviors X Prestige interaction, we examined the levels of independent variables based on the levels of moderator variables. To establish low and high values as a default setting, the 16th and 84th percentiles of the moderator variable by PROCESS are taken into consideration (Hayes, 2018). In our analysis when the prestige level is low, the association between Inadequate Leadership Skills, Unethical Behaviors, and emotional exhaustion (b = 0.25, 0.11 < 95% CI < 0.39), was relatively low. In contrast, when the prestige was high, Inadequate Leadership Skills and Unethical Behaviors were relatively highly related to emotional exhaustion (b = 0.54, 0.40 < 95% CI < 0.67). As the level of prestige increases, Inadequate Leadership Skills, Unethical Behaviors, and emotional exhaustion association also increase. This demonstrates that prestige strengthens the relationship between Inadequate Leadership Skills and Unethical Behaviors and Emotional Exhaustion. Along this line, we can say that prestige positively moderates the relationship between Inadequate Leadership Skills and Unethical Behaviors, and Emotional Exhaustion. This result validates the study’s second hypothesis.

To figure out the mechanism of the moderating effect of prestige, a simple slope plot was drawn as seen in Fig. 1. It shows that in the case of a low level of prestige (dashed line) the increase in the Inadequate Leadership Skills and Unethical Behaviors leads to a moderately significant difference in emotional exhaustion. However, in the case of a high level of prestige (dashed straight line) differences in the Inadequate Leadership Skills and Unethical Behaviors lead to a relatively higher significant change in emotional exhaustion.

To understand the interaction of the Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes X Hierarchy interaction, we examined the levels of independent variables according to the levels of moderator variables. To establish low and high values as a default setting, the 16th and 84th percentiles of the moderator variable by PROCESS are taken into consideration (Hayes, 2018). In our analysis when the hierarchy level is low, the association between Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes and emotional exhaustion (b = 0.28, 0.12 < 95% CI < 0.43), was relatively low. On the contrary, when the hierarchy was high, the Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes was relatively highly related to emotional exhaustion (b = 0.49, 0.35 < 95% CI < 0.63). As the level of hierarchy increases, the Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes and emotional exhaustion association also increase. This shows that hierarchy strengthens the relationship between the Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes and emotional exhaustion. Accordingly, we can say that hierarchy positively moderates the relationship between the Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes and emotional exhaustion. This finding supports the second hypothesis of the study.

To figure out the mechanism of the moderating effect of hierarchy, the basic slope plot was created, as seen in Fig. 2. It shows that in the case of a low level of hierarchy (dashed line) the increase in the Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes leads to a moderately significant difference in emotional exhaustion. However, in the case of a high level of hierarchy (dashed straight line) differences in the Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes lead to a relatively higher significant change in emotional exhaustion.

To understand the interaction of the Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes X Prestige interaction we examined the levels of independent variables according to the levels of moderator variables. To establish low and high values as a default setting, the 16th and 84th percentiles of the moderator variable by PROCESS are taken into consideration (Hayes, 2018). In our analysis when the prestige level is low, the association between the Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes and emotional exhaustion (b = 0.27, 0.13 < 95% CI < 0.42), was relatively low. On the contrary, when the prestige was high, the Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes was relatively highly related to emotional exhaustion (b = 0.54, 0.39 < 95% CI < 0.68). As the level of prestige increases, the Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes, and emotional exhaustion association also increase. This shows that prestige strengthens the relationship between the Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes and emotional exhaustion. Accordingly, we can say that prestige positively moderates the relationship between the Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes and emotional exhaustion. This finding supports the second hypothesis of the study.

To figure out the mechanism of the moderating effect of prestige, the basic slope plot was created, as seen in Fig. 3. It shows that in the case of a low level of prestige (dashed line) the increase in Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes leads to a moderately significant difference in emotional exhaustion. However, in the case of a high level of prestige (dashed straight line) differences in Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes lead to a relatively higher significant change in emotional exhaustion.

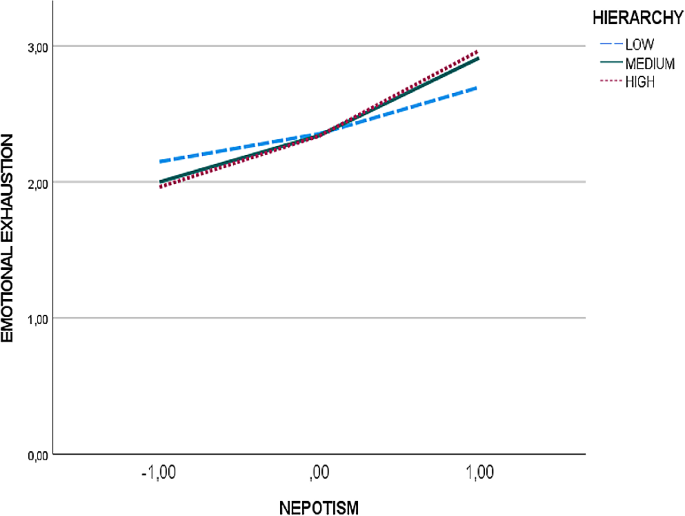

To figure out the mechanism of the moderating effect of the Nepotism X Hierarchy interaction we examined the levels of independent variables according to the levels of moderator variables. To establish low and high values as a default setting, the 16th and 84th percentiles of the moderator variable by PROCESS are taken into consideration (Hayes, 2018). In our analysis when the hierarchy level is low, the association between Nepotism and emotional exhaustion (b = 0.21, 0.08 < 95% CI < 0.33), was relatively low. On the contrary, when the hierarchy was high, Nepotism was relatively highly related to emotional exhaustion (b = 0.38, 0.26 < 95% CI < 0.49). As the level of hierarchy increases, Nepotism, and emotional exhaustion association also increase. This shows that hierarchy strengthens the relationship between Nepotism and emotional exhaustion. Accordingly, we can say that hierarchy positively moderates the relationship between Nepotism and emotional exhaustion. This finding supports the second hypothesis of the study.

To figure out the mechanism of the moderating effect of hierarchy, the basic slope plot was drawn as seen in Fig. 4. It shows that in the case of a low level of hierarchy (dashed line) the increase in Nepotism leads to a moderately significant difference in emotional exhaustion. However, in the case of a high level of hierarchy (dashed straight line) differences in Nepotism lead to a relatively higher significant change in emotional exhaustion.

Discussion and conclusion

The study holds some important theoretical implications. The findings of this study offer valuable insights into the moderating role of newly conceptualized Psychological Power Distance (PPD) on the relationship between Destructive Leadership (DL) and Emotional Exhaustion (EE). First, our empirical results support previous research findings regarding the positive correlation between negative leadership styles such as toxic and narcissistic (e.g., Badar et al., 2023) and EE. Similar to the findings of Abubakar et al.‘s (2017) study on nepotism and workplace withdrawal, nepotism, one of the components of DL, was found to be positively correlated (r = 0.40, p <.01) with EE. Hierarchy and nepotism pose risks in different forms (Tytko et al., 2020). A great example is the risk of possible downfall when concentrating all power on a small group of privileged relatives and the organs of that group. Also, it explains in terms of the risk of mutual support under hierarchy. When a society is structured in a certain way and has a social structure that allows powerful groups to protect each other’s interests, as is common in Middle Eastern societies, the privilege of that group is guaranteed (Shamaileh & Chaábane, 2022). And this mutual reinforcement can be a stable thing over time. Subsequently, the risks and consequences of these dysfunctional and corruptive practices in the context of organizational performance may also be possible.”

On the other hand, we can discuss our empirical results based on the concept of Perceived external prestige (Kamasak & Bulutlar, 2008) and social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 2004), which are also shaped around the concepts of social value and status. “According to the literature, perceived external prestige, unlike corporate image or corporate reputation, is based on employees’ beliefs (Šulentić et al., 2017). Within this framework, when we look at the items measuring the prestige dimension of PPD, we encounter statements that gaining respect and status is important for employees to exert social influence (Cheng et al., 2013). Previous studies have shown that the concept of prestige/status is also associated with EE (Sessions et al., 2022) and narcissism which is one of the main characteristics of DL (e.g., Cheng et al., 2010; Haertel et al., 2023; Zeigler et al., 2019). Correlationally, our empirical findings also show that prestige also strengthens the relationship between inadequate leadership skills, unethical behaviors, and EE. Besides, This study also created new information about the moderating role of some specific sub-dimensions of PPD in the relationship between DL and EE. Furthermore, the prestige aspect of PPD amplifies the influence of deficient leadership abilities and unethical conduct on EE.

On the other hand, “hierarchies may produce undesirable or dysfunctional consequences” in organizations (Magee & Galinsky, 2008; Leavitt, 2005). In this context, the fact that differences in Nepotism lead to a relatively higher significant change in EE in case the hierarchy is high can be considered as an empirical finding that may lead to undesirable and dysfunctional results in the organizational context. Additionally, in the context of this research, a specific mediating link of prestige/status seeking emerged in the effect of destructive leadership style on EE. Although this finding is limited, it can be generalized to Middle Eastern countries (e.g., Syria, Lebanon, Iraq) where power distance is high. Therefore, The study holds some managerial implications. These results may assist organizations and leadership training experts in developing interventions to reduce employee EE and abusive supervisory behaviors. In addition, the interactional effect of high levels of hierarchy on the relationship between DL and EE also sheds light on the cultural and psychological processes in societies where PPD is high.

When the prestige was high, the Inability to Deal with New Technology and Other Changes was relatively highly related to EE (b = 0.54, 0.39 < 95% CI < 0.68). In other words, as the level of prestige increases, the challenges of inability to adopt new technology, and EE association also increase. This shows that prestige strengthens the relationship between the challenges of the inability to adopt new technology and EE. Most of the time, it is seen that introducing new technology to the workplace may create fear in the employees. Techniques such as training, communication, and support should be used by the management to minimize these challenges (Ivanov et al., 2020). In this context, power distance measures the extent to which subordinates accept control from their leaders or supervisors, or the extent of freedom that they can practice their own beliefs, values, and behaviors (Guzman & Fu, 2022). In high power distance cultures, subordinates are not allowed to raise their voice to their supervisor- no matter right or wrong they think. Traditionalists think that this rigid stratification may stop the implementation of new technology developed in high power distance countries like China or Malaysia (e.g., Rithmire, 2023). In conclusion, our empirical findings point out a well-established path for future study which focuses on the impact of power distance theories on organizational behavior like technology adaptation.

In a recent research by Harms and his colleagues, they found that the negative effects of DL on EE (Hattab et al. 2022) could be reduced by PPD. This means that when subordinates do not perceive a large power distance between them and their leaders, the harmful effect of DL on EE may be minimized. This may be because when subordinates have low PPD from their leaders, they are likely to question the necessity of coping with EE and evaluate demands made by the leaders. On the contrary, when subordinates perceive a large psychological power distance, they are more likely to accept the situation and engage in EE because it is a reflection of decorum or cultural practices. Moreover, it has been suggested that different cultures have their norms about what is good or bad leadership, and these norms can be reflected in the perception of PPD. Investigating the role of power distance in employees’ perception of leaders and better understanding the impact of leaders on employee well-being, will not only inform practices for workplace health intervention but also enlighten leadership researchers in discussing the universal and contingency theory of leadership.

The study of the moderating role of PPD will be advantageous for the following reasons. Firstly, fostering a transparent and merit-based work culture in high PPD countries is a way to reduce and prevent nepotism in the employment setting (Kirya, 2020). Secondly by identifying how and under what circumstances different types of leaders may impact differently on employees, human resource practitioners will have better insight into leader selection and training. For example, if an organization operates in a relatively low power distance culture such as the United States (Hofstede, 2001), then the findings from our research suggest that both supportive and directive leadership styles may be effective in reducing employees’ EE. However, if the same organization aims to expand to countries with higher power distance, especially those in the Middle East, it will be beneficial to have leaders with less directive and more supportive leadership styles in charge. In this circumstance, human resource practitioners can use the cultural dimensions of different societies such as power distance to evaluate the suitability of leaders’ approaches and make necessary modifications.

Limitations and future research directions

Because most concepts in the social sciences are interrelated in some way, theoretical frameworks that provide a holistic perspective are particularly important in facilitating research.

Therefore, in order not to expand the scope of the research too much, thereby the theoretical structure is limited to specific correlated variables. On the other hand, organizations are rich in complex interpersonal interactions, and these relational dynamics, combined with unique organizational factors, can differentiate the relationship of DL and EE from one organization to another. Besides, culture is another important antecedent predictor in terms of organizational outcomes. For example, the culture that affects the follower’s questioning, ethical decision-making, or tolerance of the unethical behavior of the supervisor (Cohen, 1995). Therefore, it should not be ignored that the level of EE may differ depending on the level of exposure to DL along with culture, situational circumstances, level of motivation, or personality characteristics of employees.

The PPD is a newly conceptualized notion. In this context, we also believe that the hypothesis and the results of our study may lead to new research questions for unexplored fields. In addition, there are several practical implications within our research. We explained the organic mechanism between DL and EE under the moderation of PPD. In this sense, employees and practitioners need to understand the motivation and psychological contract (Rousseau, 1990) level of employees under the reign of DL. On the other hand, based on our conceptual elaboration in this paper, we also suggest future research on gender, because, male and female forms of destructive leadership can differ significantly in terms of gender barriers and catalysts such as role fit. Finally the complex nature of the research variables, qualitative research is needed to explore which individual resources (e.g., self-efficacy) or behaviors will be negatively affected to cope with destructive leaders. As an additional comment, the significant effect of hierarchy on emotional exhaustion in the Turkish sample, where power distance is high (Hofstede, 2001) could be a starting point for future research in the context of the impact of cultural homogenization/globalization via internal uniformity (Conversi, 2014).

This study has some limitations. First of all, this study is conducted in a rather small region in Türkiye. Examining this research model at the international level in different provinces and different cultures will make strong contributions to the literature. The second is the investigation of the proposed causal relationship through the application of a cross-sectional research methodology. Thirdly, because our study relies on self-reported questionnaires, it is susceptible to common method biases and social desirability.

References

Abubakar, A. M., Namin, B. H., Harazneh, I., Arasli, H., & Tunç, T. (2017). Does gender moderates the relationship between favoritism/nepotism, supervisor incivility, cynicism and workplace withdrawal: A neural network and SEM approach. Tourism Management Perspectives, 23, 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.06.001

Adamovic, M. (2023). Breaking down power distance into 5 dimensions. Personality and Individual Differences, 208, 112178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2023.112178

Ahmad, A. R., ALHAMMADI, A. H. Y., & Jameel, A. S. (2021). National culture, leadership styles and job satisfaction: An empirical study in the United Arab Emirates. The Journal of Asian Finance Economics and Business, 8(6), 1111–1120. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no6.1111

Aïssaoui, R., & Fabian, F. (2015). The French paradox: Implications for variations in global convergence. Journal of International Management, 21(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intman.2014.12.004

Aydinay, M., Cakici, A., & Cakici, A. (2022). The effect of destructive leadership on self-efficacy and counterproductive work behaviors: A research on service sector employees in Mersin, Turkey. Journal of Global Business Insights, 6(2), 186-206. https://www.doi.org/10.5038/2640-6489.6.2.1166

Badar, K., Aboramadan, M., & Plimmer, G. (2023). Despotic vs narcissistic leadership: Differences in their relationship to emotional exhaustion and turnover intentions. International Journal of Conflict Management, 34(4), 818–837. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCMA-12-2022-0210

Baig, S. A., Iqbal, S., Abrar, M., Baig, I. A., Amjad, F., Zia-ur-Rehman, M., & Awan, M. U. (2021). Impact of leadership styles on employees’ performance with moderating role of positive psychological capital. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 32(9–10), 1085–1105. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2019.1665011

Bakker, A. B., & Costa, P. L. (2014). Chronic job burnout and daily functioning: A theoretical analysis. Burnout Research, 1(3), 112–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2014.04.003

Bianchi, M., Giacomini, E., Crinelli, R., Radici, L., Carloni, E., & Magnani, M. (2015). Dynamic transcription of ubiquitin genes under basal and stressful conditions and new insights into the multiple UBC transcript variants. Gene, 573(1), 100-109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2015.07.030

Bono, J. E., Foldes, H. J., Vinson, G., & Muros, J. P. (2007). Workplace emotions: The role of supervision and leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1357

Brislin, R., Lonner, W., & Thorndike, R. (1973). Cross-cultural Research methods. John Wiley.

Brouwers, M., & Paltu, A. (2020). Toxic leadership: Effects on job satisfaction, commitment, turnover intention and organisational culture within the South African manufacturing industry. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(1), 1–11. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-1fa457614d

BurnsJr, W. A. (2021). A typology of destructive leadership: Pseudotransformational, laissez- faire, and unethical causal factors and predictors. Destructive Leadership and Management Hypocrisy: Advances in theory and practice (pp. 49–66). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Byrne, A., Dionisi, A. M., Barling, J., Akers, A., Robertson, J., Lys, R., & Dupre, K. (2014). The depleted leader: The influence of leaders’ diminished psychological resources on leadership behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 25, 344–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2013.09.003

Cable, D. M., & Edwards, J. R. (2004). Complementary and supplementary fit: a theoretical and empirical integration. Journal of applied psychology, 89(5), 822. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.822

Carl, D., Gupta, V., & Javidan, M. (2004). Power distance. Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of, 62(2004), 513-563.

Cascio, W. F., & Aguinis, H. (2008). Research in industrial and organizational psychology from 1963 to 2007: Changes, choices, and trends. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(5), 1062–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.5.1062

Chang, M. L. (2009). An appraisal perspective of teacher burnout: Examining the emotional work of teachers. Educational Psychology Review, 21, 193–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-009-9106-y

Chen, X., & Cheung, Y. W. (2020). School characteristics, strain, and adolescent delinquency: A test of macro-level strain theory in China. Asian Journal of Criminology, 15(1), 65–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-019-09296-x

Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., & Henrich, J. (2010). Pride, personality, and the evolutionary foundations of human social status. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31(5), 334–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.02.004

Cheng, J. T., Tracy, J. L., Foulsham, T., Kingstone, A., & Henrich, J. (2013). Two ways to the top: Evidence that dominance and prestige are distinct yet viable avenues to social rank and influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(1), 103. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030398

Chi, S. C. S., & Liang, S. G. (2013). When do subordinates’ emotion-regulation strategies matter? Abusive supervision, subordinates’ emotional exhaustion, and work withdrawal. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2012.08.006

Chiaburu, D. S., Chakrabarty, S., Wang, J., & Li, N. (2015). Organizational support and citizenship behaviors: A comparative crosscultural meta-analysis. Management International Review, 55(5), 707–736. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-015-0253-8

Cohen, D. V. (1995). Creating ethical work climates: A socioeconomic perspective. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 24(2), 317-343. https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-5357(95)90024-1

Conversi, D. (2014). Between the hammer of globalization and the anvil of nationalism: Is Europe’s complex diversity under threat? Ethnicities, 14(1), 25–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796813487727

Cordes, C. L., & Dougherty, T. W. (1993). A review and integration of research on job burnout. Academy of Management Review, 18, 621–656. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1993.9402210153

d’Iribarne, P. (1996). The usefulness of an ethnographic approach to the international comparison of organizations. International Studies of Management & Organization, 26(4), 30–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.1996.11656693

De Clercq, D., Fatima, T., & Jahanzeb, S. (2021). Ingratiating with despotic leaders to gain status: The role of power distance orientation and self-enhancement motive. Journal of Business Ethics, 171(1), 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04368-5

Ding, J., Qiao, P., Wang, J., & Huang, H. (2022). Impact of food safety supervision efficiency on preventing and controlling mass public crisis. Front Public Health, 10(1052273). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.105227

Dorfman, P., & Howell, J. P. (1988). Dimensions of national culture and effectiveleadership patterns: Hofstede revisited. In R. N. Farmer, & E. G. McGoun (Eds.),Advances in international comparative management. London, England: JAI Press, 172-150.

Einarsen, S., Aasland, M. S., & Skogstad, A. (2007). Destructive leadership behaviour: A definition and conceptual model. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(3), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.002

Ergin, C. (1992). Doktor ve hemşirelerde tükenmişlik ve Maslach Tükenmişlik Ölçeğinin uyarlanması, VII. Ulusal Psikoloji Kongresi, Hacettepe Üniversitesi, Ankara.

Farh, J. L., Hackett, R. D., & Liang, J. (2007). Individual-level cultural values as moderators of perceived organizational support–employee outcome relationships in China: Comparing the effects of power distance and traditionality. Academy of management journal, 50(3), 715-729. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.25530866

Fors Brandebo, M. (2020). Destructive leadership in crisis management. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 41(4), 567–580. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-02-2019-0089

Fors Brandebo, M., Nilsson, S., & Larsson, G. (2016). Leadership: Is bad stronger than good? Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 37(6), 690–710. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-09-2014-0191

Gkorezis, P., Petridou, E., & Krouklidou, T. (2015). The detrimental effect of machiavellian leadership on employees’ emotional exhaustion: Organizational cynicism as a mediator. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 11(4), 619. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v11i4.988

Glasø, L., & Vie, T. L. (2009). Toxic emotions at work. Scandinavian Journal of Organizational Psychology, 2, 13–16.

Gonzalez, N. L., (2021). The impact of culture on business negotiations. Honors Projects. 839. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/honorsprojects/839

Gooty, J., Connelly, S., Griffith, J., & Gupta, A. (2010). Leadership, affect and emotions: A state of the science review. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(6), 979-1004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.10.005

Guzman, F. A., & Fu, X. (2022). Leader–subordinate congruence in power distance values and voice behaviour: A person–supervisor fit approach. Applied Psychology, 71(1), 271–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12320

Haertel, T. M., Leckelt, M., Grosz, M. P., Kuefner, A. C., Geukes, K., & Back, M. D. (2023). Pathways from narcissism to leadership emergence in social groups. European Journal of Personality, 37(1), 72–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/08902070211046266

Hattab, S., Wirawan, H., Salam, R., Daswati, D., & Niswaty, R. (2022). The effect of toxic leadership on turnover intention and counterproductive work behaviour in Indonesia public organisations. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 35(3), 317–333. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-06-2021-0142

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based perspective (2nd ed.). The Guilford.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. Martino Publishing.

Hetrick, A. L., Mitchell, M. S., Villarosa-Hurlocker, M. C., & Sullivan, T. S. (2022). The consequence of unethical leader behavior to Employee Well-Being: Does support f rom the Organization mitigate or exacerbate the stress experience? Human Performance, 35(5), 323–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2022.2123486

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resources theory: Its implication for stress, health, and resilience. The Oxford Handbook of Stress Health and Coping, 127, 147.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values, abridged version. Sage Publications.

Hofstede, G. (1991). Empirical models of cultural differences. In N. Bleichrodt & P. J. D. Drenth (Eds.), Contemporary issues in cross-cultural psychology (pp. 4–20). Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions andorganizations across nations. Sage Publications.

Hsieh, C. W., Jin, M. H., & Guy, M. E. (2011). Consequences of work-related emotions: Analysis of a cross-section of public service workers. The American Review of Public Administration, 42(1), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074010396078

Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and postmodernization: Cultural, economic, and political change in 43 societies. Princeton University Press.

Ivanov, S., Kuyumdzhiev, M., & Webster, C. (2020). Automation fears: Drivers and solutions. Technology in Society, 63, 101431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101431

Jiao, Y. C., & Wang, Y. C. (2023). Under the mask: The double-edged sword effect of leader self-sacrifice on employee work outcomes. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1052623.

Jonason, P. K., Czerwiński, S. K., Tobaldo, F., Ramos-Diaz, J., Adamovic, M., Adams, B. G., & Sedikides, C. (2022). Milieu effects on the Dark Triad traits and their sex differences in 49 countries. Personality and Individual Differences, 197, 111796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111796

Kamasak, R., & Bulutlar, F. (2008). The impact of communication climate and job satisfaction in employees’ external Prestige perceptions. Yönetim Ve Ekonomi, 18(2), 133–144.

Kelemen, T. K., Matthews, S. H., & Breevaart, K. (2020). Leading day-to-day: A review of the daily causes and consequences of leadership behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 31(1), 101344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2019.101344

Khakhar, P., & Rammal, H. G. (2013). Culture and business networks: International business negotiations with Arab managers. International Business Review, 22(3), 578-590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2012.08.002

Kirya, M. T. (2020). Promoting anti-corruption, transparency and accountability in the recruitment and promotion of health workers to safeguard health outcomes. Global Health Action, 13(sup1), 1701326. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2019.1701326

Koç, O., Bozkurt, S., Taşdemir, D. D., & Günsel, A. (2022). The moderating role of intrinsic motivation on the relationship between toxic leadership and emotional exhaustion. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1047834. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1047834

Kong, M., & Jogaratnam, G. (2007). The influence of culture on perceptions of service employee behavior. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 17(3), 275–297. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520710744308

Korkmazyurek, Y., & Korkmazyurek, H. (2023). The gravity of culture on project citizenship behaviors. Current Psychoogyl, 42, 27415–27427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03849-7

Krasikova, D. V., Green, S. G., & LeBreton, J. M. (2013). Destructive leadership: A theoretical review, integration, and future research agenda. Journal of Management, 39(5), 1308–1338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312471388

Krumov, K., Negruti, A., Hristova, P., & Krumova, A. (2016). Perceptions of toxic leaders- empirical research. J Innov Entrep Sustain Dev, 1, 3–17.

Lam, C. K., Walter, F., & Huang, X. (2017). Supervisors’ emotional exhaustion and abusive supervision: The moderating roles of perceived subordinate performance and supervisor self-monitoring. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(8), 1151–1166. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2193

Lam, S. S., Schaubroeck, J., & Aryee, S. (2002). Relationship between organizational justice and employee work outcomes: a cross‐national study. Journal of organizational behavior, 23(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.131

Larsson, G., Fors Brandebo, M., & Nilsson, S. (2012). Destrudo-L: Development of a short scale designed to measure destructive leadership behaviours in a military context. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 33(4), 383–400.

Leavitt, H. J. (2005). Top down: Why hierarchies are here to stay and how to manage them more effectively. (No Title).

Leonidou, L. C., Aykol, B., Larimo, J., Kyrgidou, L., & Christodoulides, P. (2021). Enhancing international buyer-seller relationship quality and long-term orientation using emotional intelligence: The moderating role of foreign culture. Management International Review, 61(3), 365–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-021-00447-w

Li, W., Lu, Y., Makino, S., & Lau, C. M. (2017). National power distance, status incongruence, and CEO dismissal. Journal of World Business, 52(6), 809–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2017.08.001

Liao, Z., Lee, H. W., Johnson, R. E., Song, Z., & Liu, Y. (2021). Seeing from a short-term perspective: When and why daily abusive supervisor behavior yields functional and dysfunctional consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(3), 377. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000508

Lindholm, C. (2008). The Islamic middle east: tradition and change. John Wiley & Sons.

Loi, R., Lai, J. Y., & Lam, L. W. (2012). Working under a committed boss: A test of the relationship between supervisors’ and subordinates’ affective commitment. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(3), 466–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.12.001

Mackey, J. D., Ellen III, B. P., McAllister, C. P., & Alexander, K. C. (2021). The dark side of leadership: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of destructive leadership research. Journal of Business Research, 132, 705-718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.037

Mackey, J. D., McAllister, C. P., Maher, L. P., & Wang, G. (2019). Leaders and followers behaving badly: A meta-analytic examination of curvilinear relationships between destructive leadership and followers’ workplace behaviors. Personnel Psychology, 72(1), 3–47.

Magee, J. C., & Galinsky, A. D. (2008). 8 social hierarchy: The self-reinforcing nature of power and status. The Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 351–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520802211628

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1996). Maslach Burnout Inventory manual (3rd ed.). Consulting Psychologists Press.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

Matta, S., Rogova, N., & Luna-Cortés, G. (2022). Investigating tolerance of uncertainty, COVID-19 concern, and compliance with recommended behavior in four countries: The moderating role of mindfulness, trust in scientists, and power distance. Personality and Individual Differences, 186, 111352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111352

Maznevski, M. L., Gomez, C. B., DiStefano, J. J., Noorderhaven, N. G., & Wu, P. C. (2002). Cultural dimensions at the individual level of analysis: The cultural orientations framework. International journal of cross cultural management, 2(3), 275-295. https://doi.org/10.1177/147059580223001

Meydan, C. H., Basim, H. N., & BASAR, U. (2014). Power distance as a moderator of the relationship between organizational citizenship behavior and impression management. Eurasian Journal of Business and Economics, 7(13), 105–118.

Moon, T. W., & Hur, W. M. (2011). Emotional intelligence, emotional exhaustion, and job performance. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 39(8), 1087–1096. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2011.39.8.1087

Murad, M., Jiatong, W., Shahzad, F., & Syed, N. (2021). The influence of despotic leadership on counterproductive work behavior among police personnel: Role of emotional exhaustion and organizational cynicism. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 36(3), 603–615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-021-09470-x

Naseer, S., & Raja, U. (2021). Why does workplace bullying affect victims’ job strain? Perceived organization support and emotional dissonance as resource depletion mechanisms. Current Psychology, 40(9), 4311–4323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00375-x

Obi, I. M. O., Bollen, K., Aaldering, H., Robijn, W., & Euwema, M. C. (2020). Servant leadership, third-party behavior, and emotional exhaustion of followers. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research. https://doi.org/10.1111/ncmr.12184

Ojo, O. (2012). Influence of organizational culture on employee work behavior. International Journal of Contemporary Business Studies, 3(11), 46–57.

Peng, J., Li, M., Wang, Z., & Lin, Y. (2021). Transformational leadership and employees’ reactions to organizational change: Evidence from a meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 57(3), 369–397. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886320920366

Pillay, J., & April, K. (2022). Developing Leadership Maturity: Ego Development and Personality Coaching. Effective Executive, 25(1), 40–73.

Qiu, P., Yan, L., Zhang, Q., Guo, S., Liu, C., Liu, H., & Chen, X. (2023). Organizational display rules in nursing: Impacts on caring behaviors and emotional exhaustion through emotional labor. International Nursing Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12876

Rao, A. N., & Pearce, J. L. (2016). Should management practice adapt to cultural values? The evidence against power distance adaptation. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 23(2), 1–49. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-03-2014-0035

Rasid, S. Z. A., Manaf, M. A. A., & Quoquab, F. (2013). Leadership and organizational commitment in the islamic banking context: The role of organizational culture as a mediator. American Journal of Economics, 3(5), 171–176. https://doi.org/10.5923/c.economics.201301.29

Rattrie, L. T., Kittler, M. G., & Paul, K. I. (2020). Culture, burnout, and engagement: A meta- analysis on national cultural values as moderators in JD‐R theory. Applied Psychology, 69(1), 176–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12209

Rithmire, M. (2023). Precarious ties: Business and the state in authoritarian Asia. Oxford University Press.

Rosenstein, A. (2017). Disruptive and unprofessional behaviors. In K. Brower, & M. Riba (Eds.), Physician Mental Health and Well-Being. Integrating Psychiatry and Primary Care. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55583-6_3

Rousseau, D. M. (1990). New hire perceptions of their own and their employer’s obligations: A study of psychological contracts. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 11(5), 389–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030110506

Rumjaun, A., & Narod, F. (2020). Social Learning Theory—Albert Bandura. Science education in theory and practice: An introductory guide to learning theory (pp. 85–99)

Ryan, P., Odhiambo, G., & Wilson, R. (2021). Destructive leadership in education: A transdisciplinary critical analysis of contemporary literature. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 24(1), 57–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2019.1640892

Salas-Vallina, A., Alegre, J., & López‐Cabrales, Á. (2021). The challenge of increasing employees’ well‐being and performance: How human resource management practices and engaging leadership work together toward reaching this goal. Human Resource Management, 60(3), 333–347. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22021

Schilling, J., & Schyns, B. (2015). The causes and consequences of bad leadership. Zeitschrift für Psychologie. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000185

Schmid, E. A., Verdorfer, P., A., & Peus, C. (2019). Shedding light on leaders’ self- interest: Theory and measurement of exploitative leadership. Journal of Management, 45(4), 1401–1433. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317707810

Schwartz, S. H. (2014). National culture as value orientations: Consequences of value differences and cultural distance. In Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture (Vol. 2, pp. 547-586). Elsevier.

Sessions, H., Nahrgang, J. D., Baer, M. D., & Welsh, D. T. (2022). From zero to hero and back to zero: The consequences of status inconsistency between the work roles of multiple jobholders. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(8), 1369. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000935

Shahzad, K., Iqbal, R., Nauman, S., Shahzadi, R., & Luqman, A. (2023). How a despotic project manager jeopardizes Project Success: The role of Project Team Members’ emotional exhaustion and Emotional Intelligence. Project Management Journal, 54(2), 194–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/87569728221145891

Shamaileh, A., & Chaábane, Y. (2022). Institutional favoritism, income, and political trust: Evidence from Jordan. Comparative Politics, 54(4), 741–764. https://doi.org/10.5129/001041522X16331935725154

Shore, B., & Cross, B. J. (2005). Exploring the role of national culture in the management of large scale international science projects. International Journal of Project Management,23, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2004.05.009

Strack, J., Lopes, P. N., & Esteves, F. (2015). Will you thrive under pressure or burn out? Linking anxiety motivation and emotional exhaustion. Cognition and Emotion, 29(4), 578–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2014.922934

Šulentić, T. S., Žnidar, K., & Pavičić, J. (2017). The key determinants of perceived external prestige (PEP)–qualitative research approach. Management: Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 22(1), 49.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (2004). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. Political psychology (pp. 276–293). Psychology Press.

Tang, G., Chen, Y., van Knippenberg, D., & Yu, B. (2020). Antecedents and consequences of empowering leadership: Leader power distance, leader perception of team capability, and team innovation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(6), 551–566. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2449

Taras, V. (2014). Catalogue of instruments for measuring culture. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266520890_Catalogue_of_Instruments_for_Measuring_Culture

Tavakol, M., & Wetzel, A. (2020). Factor Analysis: a means for theory and instrument development in support of construct validity. International Journal of Medical Education,6(11), 245–247. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5f96.0f4a. PMID: 33170146; PMCID: PMC7883798.

Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–190. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556375

Tepper, B. J. (2007). Abusive supervision in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 33(3), 261–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307300812

Tepper, B. J., Simon, L., & Park, H. M. (2017). Abusive supervision. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 123–152. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062539

Tytko, A., Smokovych, M., Dorokhina, Y., Chernezhenko, O., & Stremenovskyi, S. (2020). Nepotism, favoritism and cronyism as a source of conflict of interest: Corruption or not? Amazonia Investiga, 9(29), 163–169. https://doi.org/10.34069/AI/2020.29.05.19

Veldsman, T. H. (2012). The growing cancer endangering organisations: Toxic leadership. Conference on Leadership in Emerging Countries presented by Department of Industrial Psychology and People Management, Faculty of Management, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg.

Wang, M., Sinclair, R., & Deese, M. N. (2010). Understanding the causes of destructive leadership behavior: A dualprocess model. In B. Schyns, & T. Hansbrough (Eds.), When leadership goes wrong: Destructive leadership, mistakes, and ethical failures (pp. 73–97). Information Age.

Weigl, M., Beck, J., Wehler, M., & Schneider, A. (2017). Workflow interruptions and stress at work: a mixed-methods study among physicians and nurses of a multidisciplinary emergency department. BMJ open, 7(12), e019074. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019074

Weiner, B. (1985). An attributional theory of achievement motivation and emotion. Psychological Review, 92(4), 548–573.

Yang, J. S. (2020). Differential moderating effects of collectivistic and power distance orientations on the effectiveness of work motivators. Management Decision, 58(4), 644–665. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-10-2018-1119

Yazıcıoğlu, Y., & Erdoğan, S. (2004). SPSS applied scientific research methods. Detay Publishing.

Zeigler-Hill, V., Vrabel, J. K., McCabe, G. A., Cosby, C. A., Traeder, C. K., Hobbs, K. A., & Southard, A. C. (2019). Narcissism and the pursuit of status. Journal of Personality, 87(2), 310–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12392

Zhang, Y., & Liao, Z. (2015). Consequences of abusive supervision: A meta-analytic review. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 32, 959–987. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-015-9425-0

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Korkmazyurek, Y., Ocak, M. The moderating role of psychological power distance on the relationship between destructive leadership and emotional exhaustion. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06016-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06016-2