Abstract

Research on autistic women’s experience of parenthood is lacking. In this paper, two studies are presented. Study 1 comprised a small-scale qualitative study with autistic mothers (n = 9) in which their experiences of motherhood were explored using thematic analysis. The findings showed that participants identified a range of strengths, including connection with their children, high knowledge about childhood, a reflective style of parenting, good coping strategies, identifying with their autism diagnosis, and not caring what others thought. They also identified difficulties, including sensory challenges, coping with uncertainty and change, having to socialise, managing exhaustion, and not being taken seriously by professionals involved with their children. Guided by the findings of Study 1, and in collaboration with an advisory panel of autistic mothers, an online survey using mixed methods was completed by education and social professionals (n = 277) to investigate their understanding of, and attitudes towards, autism in women and mothers. Results showed high awareness and positive attitudes towards autism, but low levels of self-efficacy in working with autistic adults. Qualitative content analysis of open-ended questions shed light on challenges and rewards of working with autistic parents. The findings are discussed with reference to the double empathy problem (Milton Disability & Society, 27(6), 883–887, 2012) and implications for training of professionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Autism as a clinical condition is characterised by differences in social communication, repetitive behaviour, and circumscribed interests from early childhood (DSM-5: APA, 2013). From a neurodiversity perspective, autism is increasingly recognised as a neurodevelopmental difference, which brings both strengths and challenges, often becoming disabling through interaction of the individual and the contexts in which they live (Chapman, 2021; Pellicano & den Houting, 2021). While autism was once understood to occur predominantly in boys and men, progress in research and clinical practice over recent years has challenged this view and has highlighted the prevalence of autism in girls and womenFootnote 1 (Bargiela et al., 2016; Hiller et al., 2014; Hull et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2015). There is growing evidence to suggest gender-related differences in the presentation of autism (Halladay et al., 2015). A so-called ‘female autism phenotype’ may mean that autistic girls/women do not fit with the original characterisation of autism. For example, in comparison to autistic boys/men, autistic girls/women tend to show greater social interest and less stereotypical and repetitive behaviour (Hull et al., 2020), and girls’ restricted interests may align more closely with stereotyped social norms (Hull et al., 2020), although this is not universal. Autistic girls/women may not only have greater capacity for traditional friendship, but they may also display increased social motivation in comparison to autistic boys/men (Head et al., 2014; Sedgewick et al., 2016). Girls/women may also be more likely to ‘mask’ or ‘camouflage’ their autistic features (Hull et al., 2020; Mandy et al., 2012). Given the complex intersection of neurodiversity and gender diversity (Warrier et al., 2020), a binary understanding of autism in men versus women is likely to be reductionist. Notwithstanding this, autistic women (broadly defined) are at elevated risk of either being missed entirely, or misdiagnosed (Giarelli et al., 2010; Happé & Frith, 2020; Lai & Baron-Cohen, 2015). Mental health conditions are more prevalent in autistic people (Lai et al., 2019) and may be particularly pronounced for autistic girls/women (Tint et al., 2017). The autistic community has proposed that addressing the gender bias issue needs to be a priority for researchers, as it has significant ramifications for wellbeing (Pellicano et al., 2014).

Given how recent the research on autism in girls/women has been, investigations of aspects of women’s health in autism have been neglected. One such area is the experience of parenting. The transition to parenthood is a major milestone in anyone’s life, which is associated with new roles and responsibilities (Hansen, 2012). Women are more at risk of mental health problems in the peripartum period than at any other time in their lives (Webster et al., 2000). There are reasons to anticipate that motherhood in autism may present particular challenges, given how profound the changes can be, and the lack of appropriate social supports for autistic people during the transition to adulthood (Wood et al., 2018). Furthermore, due to the high heritability of autism, autistic women may be more likely to be parenting autistic children, which is associated with heightened parenting stress (Hayes & Watson, 2013). Lana Grant’s (2015) first person perspective as an autistic mother highlighted the lack of research into understanding the experience of autistic mothers and a lack of autism awareness amongst maternity professionals.

A number of empirical studies in recent years have shed light on autistic mothers’ experience. Suplee et al. (2014) conducted secondary analysis of online support groups for autistic women to understand childbearing experiences, and found women experienced difficulties with sensory sensitivity, and anxiety during interactions with professionals, but also noted high levels of adherence to healthy childrearing practices and satisfaction with parenting. This experience of sensory challenges has been found repeatedly in subsequent research: Samuel et al. (2022) conducted a systematic review of the sensory challenges experienced by autistic women during pregnancy and childbirth, encompassing four qualitative (Burton, 2016; Donovan, 2020; Gardner et al., 2016; Rogers et al., 2017) and two quantitative studies (Lum et al., 2014; Pohl et al., 2020). Studies reviewed described subsequent negative effects on autistic women’s mental health and frequent difficulty communicating with health professionals, an issue that is pervasive in the wider autistic community (Mason et al., 2019). Autistic mothers also reported difficulties in obtaining information that suited their needs and feelings of loss of control during labour, themes which have been supported by recent qualitative studies (Hampton et al., 2022b; Lewis et al., 2021).

Samuel et al. (2022) highlight that much of the research reviewed has come from the field of nursing/midwifery, and experiences outside of the medical context have not been fully explored. Studies on motherhood beyond birth have been emerging in recent years. McDonnell and Delucia (2021) conducted a systematic review which identified 8 studies related to parenting, and 7 related to pregnancy. Those related to parenting suggested challenges such as some autistic women having their ability to parent questioned by professionals, with higher rates of referral to social services and loss of custody (Griffiths et al., 2019), and having higher rates of mental health problems (Pohl et al., 2020). Dugdale et al. (2021) in a qualitative study of 9 autistic mothers described the mothers having to fight for the right support, often feeling misunderstood and dismissed by professionals. Radev et al. (2023) also found autistic parents perceived stigma around their diagnosis when interacting with statutory child services. There appear to be distinct challenges associated with autism in mothers therefore, in part related to interpersonal interactions with others but also to professionals’ negative perceptions about the capacity of autistic mothers.

Clear evidence of strengths in parenting are also emerging. Studies have identified that autistic women experience levels of parental efficacy equivalent to non-autistic women (Lau et al., 2016). In Hampton et al. (2022b)’s study of the first months of parenting, autistic women described the rewards of parenting and their particular strengths, such as being able to discriminate between their baby’s cries due to strong auditory discrimination and making aspects of parenting such as breastfeeding a focused interest. Dugdale et al. (2021) found autistic women describing intense connection and reward in their role as mothers.

Research on the parenting experiences of autistic mothers is in its infancy, and little research has specifically focused on how the attitudes of professionals with whom autistic mothers interact in relation to their children (e.g. social care and education professionals) impact their experiences of motherhood.

The current study

This study was in two parts, using a mixed methods approach with a participatory research design. The first study was designed to further explore the experience of motherhood for autistic women, in order to deepen understanding of the experience of parenting beyond pregnancy and birth. This study used qualitative analysis of semi-structured interviews– as there are still few studies exploring autistic women’s experiences, this method enabled us to keep their voices at the centre. Following the first study, participants were invited to form a project advisory panel to co-design the second study based on their own priorities for research. The second study therefore used a participatory research approach to co-design a mixed methods survey to investigate the attitudes and knowledge amongst social and education professionals relating to autism in women and mothers, and their levels of self-efficacy in supporting autistic mothers. Participatory research is crucial to ensure that investigations remain sensitive to the needs and priorities of autistic communities (Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019). Existing scales were adapted to relate specifically to autistic mothers, allowing a quantitative description of respondents’ attitudes, knowledge and self-efficacy. This was supplemented by qualitative analysis of responses to open-ended survey questions. A mixed-method approach of this kind allowed us to answer questions that neither method alone could satisfy.

Study 1 method

The first study addressed the following research question: How does being autistic impact women’s experience of parenthood?

Participants

Nine autistic mothers gave informed consent to take part in the study (Table 1). Participants were recruited via adverts on social media, mainly Facebook groups and Twitter. In advance of the interview, a research passport (based on Ashworth et al., 2021) was emailed to participants to find out their communication and participation preferences to ensure inclusivity. Inclusion criteria were women aged 18 or over with a formal diagnosis of autism and at least one child (biological or adopted). Exclusion criteria were being resident in inpatient mental health units or incarcerated, but this did not arise for any potential participant. These criteria were checked during initial email or phone contact with the research team. One woman was not included as they resided outside of the UK and did not have GP details to share in case of safeguarding concerns. Ethical approval was obtained from the relevant University committee and all testing was in line with ethical standards of the British Psychological Society and American Psychological Association.

Data collection

Participants were interviewed to understand their experience of motherhood: in line with their stated preferences, four participated over email, one participated in person and four participated via video call. The semi-structured interview questions were created from studying existing literature on autism, including autobiographical accounts of autistic mothers, and the research team’s clinical experience of working with autistic individuals (Supplementary Material). The interviews were transcribed by the first author, checked by the second and third authors, and were pseudonymised to replace any data which would identify participants or their children.

Data analysis

An inductive, reflexive thematic analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, 2006, 2013, 2020) was utilised to complete the analysis of the interviews, as this method was considered to enable the identification of pertinent issues from across the written and verbal interviews given by the participants, and it is an appropriate methodology to gain broad insights into newly emerging areas of research. The primary researcher became familiar with the interviews through multiple readings and an inductive approach was used to code the transcripts, with a focus on semantic coding to represent participant experience in a critically realist, descriptive way (Braun, Clarke, & Terry, 2014). Themes and subthemes which addressed the research questions were identified from the codes across the entire dataset and were reviewed by the primary researcher and second author, and adjustments were made to incorporate the most salient themes until the structure was finalised. The primary researcher paid attention to reflexivity through ongoing supervision discussions during the analysis process.

Study 1 results

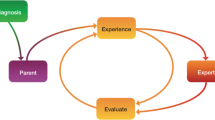

Two main themes were identified, which were Strengths in Parenting and Challenges in Parenting, with a number of subthemes (Fig. 1).

Strengths in parenting

Participants identified several ways in which being an autistic parent could be an advantage; autism provided them with valuable parenting skills, especially with a child who was also autistic. They identified ways in which they managed the demands of parenting.

Children as focused interest

A recurring theme was mothers’ ability to absorb information on children and parenting, which helped them to make decisions with confidence. “You can become quite knowledgeable, especially with…parenting styles and what’s good psychologically for children” (P7). Participants said they did not feel satisfied until they had “read everything” (P4) about a topic that they were interested in. “I’m also a bit obsessive and spend hours of my time on parenting Facebook groups and read books and articles about birth, parenting, and breastfeeding. It might have turned into a special interest” (P3). They talked about monitoring their children closely to obtain knowledge about their development, meaning they were able to assess their own and their children’s health needs in a timely manner, and they talked about researching before they attended appointments, which enabled them to advocate for their children’s needs with professionals - as one mother described her considerations about having her daughter assessed: “If I go down the route for diagnosis as well, it’s going to be a constant fight. So from an autistic perspective, having the knowledge and having gone through it before…” (P7).

Reflecting on mental states

The theme was evident when the mothers described their parent-child relationship and how they attempted to navigate their way around their own and their children’s feelings. They talked about regularly attempting to make sense of their child’s behaviours, considering their mental states, for example: “She is very quick to anger….I am not angry person so I don’t understand that reaction, when she comes out with that, so I find that difficult” (P7). They reflected on what they did when they were uncertain about how their children were feeling, sometimes using their own experiences to make sense of them: “I’m thinking about things from my perspective e.g. would fiddle toys or less background noise help at school. Is he stressed as I was?” (P3). They talked about a desire for their children to avoid the confusion and upset that they had experienced as children with regard to their autism: “I want them to have much better than my upbringing and don’t want them to experience the struggles, confusion and distress that my memories are filled with” (P2).

Connection with an autistic child

The mothers felt understood and accepted by their children and specifically experienced a high level of connectedness with their autistic children. Mothers talked about having insight into experiences which perhaps only an autistic individual would be able to understand, such as anxiety, sensory experiences and focused interests. “I think a lot of it’s around how I can understand a lot his anxieties and I know how to help him…I know when to encourage him and when to let him be” (P4). Mothers talked about connecting with their children around “intense interests and abilities to retain and learn information” (P2). They described enjoying and sharing their children’s interests and play, e.g. “He knows things that you wouldn’t even dream of knowing. I just find… he is funny and dead interesting” (P4). Some reported more uncertainty about understanding their neurotypical children as easily, e.g. “With [daughter’s name], I’m on the back foot all the time so being able to interpret where she is coming from is difficult. I don’t know whether [that’s] because she is neurotypical” (P7).

Not caring what others think

The mothers talked about their capacity to parent according to their children’s needs instead of ‘what others might think’, “being open to ideas about parenting rather than following methods because of family, friends, or traditions” (P3). They saw a strength in their ability not to feel the pressure of societal norms about themselves and their children, which allowed them to be playful and supportive. “I presume a woman in her late 30s would usually be more refined, so I like to think I can tap into my inner child a lot more when around them” (P2). Not caring what others think was also important when seeking support for their child’s health. Their strong advocacy for their children was driven by motivation to ensure their children were treated with fairness in school and healthcare settings: “I think we had to fight for every bit of the support that we had. Just even getting recognition that there was an issue was a battle” (P7).

Coping strategies

Autistic mothers described ways in which they managed the stresses inherent in parenting, including support from online groups, partners, close family, friends, charities, and religion, as well as time to themselves to be quiet or enjoy their interests. “I’ve found [an online platform] groups very helpful as I can share experiences in writing without a communication barrier and find people with similar experiences and autism who I would never talk to if relied on socialising verbally” (P3). For some, having systems and routines around parenting to guide their choices helped mitigate stress: “I loved the Gina Ford one because it said do this, this, this, and it gave me a routine and said obviously you change it if you need to. But it gave me the structure I needed” (P6). For others, allowing themselves to stim was helpful, and others spoke about deliberate self-harm (picking skin and hitting themselves) as helping to alleviate stress. The coping strategies described were often about balancing time for themselves with their children. “At home, I try to spend at least some time every day doing something for myself…this helps me to cope much better with the demands of parenting” (P9). “Being close to nature and outdoors in my garden gives me much needed headspace. Lots and lots of alone and downtime” (P2). Mothers also spoke frequently about just having to ‘get on with it’, despite what they were feeling, describing their willingness to endure discomfort for their children’s sake. “You get on with it because you are caring for your kids” (P7).

Identifying with autism

This theme emerged as a strength when mothers talked about how their own autism diagnosis gave them a sense of identity, confidence, and self-acceptance. One mother described finding Lana Grant’s book ‘From Here to Maternity’: “I sat in the library and I bawled my eyes out because suddenly somebody got it. It was amazing. I wish I had known about that book when I was pregnant…it was a brilliant book and it described what I was feeling” (P6). Becoming parents was often pivotal in the journey to diagnosis - of the nine mothers interviewed, seven received their diagnosis after becoming parents, often after a child underwent an assessment. Diagnosis allowed them to approach parenting with a sense of their strengths, challenges, and coping strategies. “The way I experience autism and need for structure and routine. I think any child typical or not, thrive with structure and routine. I feel it creates a safety for them too” (P2). “I am also good at engaging in lengthy tasks and seeing things through to completion– my children seem to find this a good model for their own behaviour, particularly when it comes to things like homework” (P9). This was particularly the case when parenting autistic children: “We celebrate every little milestone or achievement that may be overlooked within a typical family, as we know the small things are such big things in terms of the effort that has gone in to get there” (P2).

Challenges in parenting

The participants highlighted ways in which parenting is complicated by being autistic, as well as by societal stereotypes about autism. These challenges are described within five subthemes below.

Constant changes

The participants talked about motherhood changing the level of control they felt over their daily routine, which could heighten anxiety. “I also don’t know how to adapt when things don’t go according to plan– this happens frequently with children! So there are many challenging situations in this respect”(P9). Mothers spoke about the executive functioning challenges entailed in switching attention or being interrupted, and in organising the household and children: “leaving the house with kids and lots of things packed is incredibly slow and hard to cope with” (P3); “Sometimes the things I really need to do I get overwhelmed with…like meal planning” (P4). Additionally, developmental and behaviour changes in children, such as the change from more physical care to emotional care, were described as difficult by some of the mothers, sometimes creating a sense of doubt in their own abilities to meet their children’s needs. This self-doubt was expressed despite the confidence in their parenting knowledge engendered by extensive research on the subject, as described above, reflecting the complex and dynamic experience of parenting as an autistic mother.

Sensory challenges

Most mothers commented on their difficulties associated with pregnancy and increased sensitivities to touch, light, sounds and interaction, and difficulties with noise and physical contact as parents. “If there is a lot of movement around the house (running, play-fighting, etc.), I find the visual and audio processing really difficult” (P9). Mothers described conflict between their own and their children’s sensory needs and having to tolerate intense personal discomfort for their child’s benefit, e.g. breastfeeding despite sensory challenges. “My kids are sensory-seekers and I am sensory avoidant, so that’s hard” (P7). The additional appointments linked with parenthood (e.g. GP or hospital visits, school events, social outings) meant heightened sensory input, e.g. “You got people sitting close to you. You got bags and other children running around, the noises, the lights, and the buzzing noises” (P1).

Having to socialise

Motherhood brought expectations that women should attend social situations they might previously have avoided, such as mother and toddler groups, children’s parties, and appointments for children. “Children make people avoidance impossible. I need to interact with schools and their friendships. Also interactions with other parents. These types of interactions can rob me of my energies throughout the day and can then make me struggle for the rest of the day or even days to follow” (P2). Participants discussed the challenge of holding conversations in group settings and filtering out the noise of other people. These settings could raise social anxiety and were not necessarily experienced as supportive, sometimes raising fears of being judged, “When I look back I feel like I was so awkward and I was weird with people” (P4). Women described having to mask their differences in social settings, and at times making mistakes during interaction, which added to the pressure felt.

Mentally and physically exhausting

Mothers sometimes spoke about prioritising their children’s needs over their own. This, in combination with the masking of autistic behaviours in social contexts, was experienced as mentally, emotionally and physically exhausting. “I am excellent at masking…I have to survive but it’s exhausting” (P1). Some had experienced mental health difficulties, particularly anxiety and depression, which could be related to characteristics such as perfectionism: “One of the things I got very upty with was food, trying to feed my family very healthily…I really did go over the top” (P6). However, mothers described carrying on regardless, and continuing to experience joy in their role: “Aspects of parenting are just relentless and it’s a grind and it’s glorious and exhausting and it’s wonderful and it’s horrible” (P7).

Not being taken seriously

Participants recounted experiences of not being believed or taken seriously by professionals on issues regarding their children. “I find I very often get my concerns dismissed” (P5). The prospect of not being believed meant that mothers were often interacting with professionals from a defensive position. To be listened to and taken seriously, they often attended appointments prepared with facts and research. Most spoke about having to persistently fight for their and their children’s rights or services, which could be misunderstood by professionals as them being difficult, “You got to be on the ball all the time to get the right support” (P7). However, a few mentioned the benefits of having at least one professional on their side: “If you got one good professional then half the battle is done” (P4).

Study 1 interim discussion

Autistic mothers in previous studies have reported unique challenges and strengths (McDonnell & DeLucia, 2021), which were confirmed and expanded in the current study. The first encapsulated strengths in autistic parenting, including the capacity to become devoted and intensely interested in children and parenting, which enabled autistic mothers to make informed choices about their approach to child-rearing, consistent with findings from previous qualitative studies (Dugdale et al., 2021; Hampton et al., 2022a). The second subtheme described how participants deliberately reflected on mental states to understand their own and their children’s experiences. Mentalizing about children is an important and often challenging aspect of parenting for all people (Luyten et al., 2017), and the mothers in this study showed evidence of being reflective. Further research to understand these processes may be helpful to understand whether autistic parents approach parental mentalizing in particular ways. The third subtheme, ‘connection with an autistic child’ demonstrated the mutual understanding between the mothers and their autistic children in particular, consistent with previous research (Dugdale et al., 2021), although it would be interesting to further interrogate differences in parenting non-autistic and autistic children, which were alluded to in the current study. The fourth subtheme ‘not caring what others think’ demonstrated the mothers’ determination to do what was best for their children, and to be fun and carefree rather than burdened by society’s expectations. This independent spirit suggested a rejection of conformity and a more unique and inclusive perspective, characteristic of neurodiversity (Pellicano & den Houting, 2021). The fifth subtheme, ‘coping strategies’ described the many ways in which participants sought to mitigate the stress of parenting in resourceful ways. The use of online support groups was particularly striking and may represent an important mechanism for women and mothers with autism to access a supportive community, as has been found for other autistic groups (Crompton et al., 2022; Saha & Agarwal, 2016). The allusion by some mothers to deliberate self-harm as a positive coping strategy echoes previous findings that non-suicidal self-injury can be perceived as an unproblematic method of emotional regulation by autistic adults (Moseley et al., 2019). However, this is not always the case, and this finding highlights the need to ensure that mental health supports are accessible to autistic mothers who wish to utilise them. The sixth subtheme, identifying with autism, demonstrated ways in which a diagnosis increased participants’ self-acceptance. This has much in common with the reports of adults late diagnosed as autistic (Bargiela et al., 2016), and is similar to the first-person report by Grant (2015) who wrote about how her diagnosis changed her own expectations of herself as a mother.

The challenges identified were also consistent with previous studies, as well as expanding these themes. The first subtheme ‘constant changes’ highlighted how the disruption to daily routines as well as macro-level changes that parenting entailed (e.g. changing parenting approach as children grow and develop) could be particularly anxiety-provoking for autistic mothers. Intolerance of uncertainty is a psychological characteristic often found to be heightened in autism, and a driver of anxiety (Jenkinson et al., 2020). This may go some way to explaining heightened levels of mental health difficulties in autistic mothers (e.g. Pohl et al., 2020) and suggests an area where greater support may be warranted (e.g. Rodgers et al., 2018). The second subtheme ‘sensory challenges’ is consistent with previous research, as participants talked about seeing, hearing, and feeling the world differently to neurotypical individuals (Dugdale et al., 2021; Sinclair, 2012; Talcer et al., 2021), which made some of their experiences with parenting particularly challenging, sometimes leading to overwhelming anxiety and discomfort, which could then further impact their ability to engage with others and think clearly (Aylott, 2010; Baranek, 2002; Dugdale et al., 2021; Gardner et al., 2016; Milner et al., 2019; Pohl et al., 2020; Simone, 2010). This connected to the third subtheme, ‘having to socialise’, where participants found themselves having to socialise more often as parents. The associated sensory and social challenges this posed, including the need to mask when in social settings, was particularly stressful, which again can contribute to increased mental health difficulties (Bradley et al., 2021; Gould & Ashton-Smith, 2011). The fourth subtheme ‘mentally and physically exhausting’ highlighted these challenges, including additional stressors which contribute to this, such as coping with a society ill-equipped to the needs of autistic people (Higgins et al., 2021). The final subtheme, ‘not being taken seriously’, was striking, and became the topic of Study 2. While on the one hand the participants described ‘not caring what others think’ and being highly informed, on the other hand, their interactions with professionals could be particularly challenging and stigmatising. The anticipation of autism-related stigma exacerbated communication difficulties for these mothers. The findings of this study support previous research (Dugdale et al., 2021; Pohl et al., 2020; Radev et al., 2023) indicating that autistic mothers are more likely to worry about the judgments of others on their parenting and to feel isolated or unable to seek support from others with parenting. Despite the push for better understanding of autism suggested within national policies, research findings continue to highlight the lack of awareness of autism in women amongst various services (Autism Act, 2009; Department of Health, 2014; Venkat et al., 2012). Further research on professionals’ experience of working with autistic people was deemed necessary to clarify the sources of these issues.

Study 2 methods

Participatory research design

Following Study 1, the participants were invited to take part in a project advisory panel to contribute their views on the most important avenues for further research with autistic mothers: five agreed to take part, signed a consent form and were consulted about their communication preferences. The panel met twice via online conferencing and communicated via email with the researchers. The first online meeting identified the objectives and design for Study 2. It was agreed that a high priority for the researchers and advisory panel was to conduct an online survey to understand professionals’ knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy in identifying and meeting the needs of autistic women and mothers. Professionals who have regular contact with autistic mothers, in social care or educational settings, were targeted. Members of the panel reviewed the draft survey and approved the wording of the questions. At the second meeting, the findings and interpretation of the survey were presented and discussed. Finally, members were asked to review the manuscript before submission for publication. Following best practice in patient and public involvement from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) UK, all panel members were reimbursed for their time (Mockford et al., 2012; Viswanathan et al., 2004).

The aims of the survey were (1) to measure professionals’ knowledge of autism in general, and specifically in women, (2) to measure levels of self-efficacy in working with autistic people, (3) to evaluate attitudes towards autism in parents, and (4) to elicit their views on their experiences of working with autistic parents. We also sought to examine how professionals’ self-efficacy related to their knowledge of autism, attendance at training, personal experience of autism, and professional area (education versus social care). We hypothesised that knowledge of autism and attendance at training would relate to self-efficacy. We did not make a hypothesis about whether professional area would relate to self-efficacy, as there is no clear precedent in the literature on which to base this. There are reasons to anticipate that more personal experience of autism would relate to better self-efficacy, but we did not have a firm hypothesis about this given a lack of previous research.

Procedure

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the University committee and the study adhered to APA and BPS standards for the study of human participants. After ethical approval was obtained, professionals from a variety of backgrounds in education and social care in the UK, specifically those with experience of working with autistic parents, were invited to participate in an online, mixed-methods survey between December 2020 and January 2021. Recruitment was through convenience and opportunity sampling methods, using social media, autism charities, emails to headteachers, and local councils. Participants gave informed consent, and the survey took approximately 30 minutes to complete. All data were collected anonymously.

Participants

In total, 406 participants responded to the online survey. Responses were not considered for those who completed less than 60% of the survey (n = 109). Staff from education settings (n = 211 e.g. deputy headteachers, headteachers, teachers, teaching assistants, SENCO) and social care (n = 66; e.g. social workers, support workers) were recruited. A number of respondents worked in mental health settings (n = 20) but they were excluded as we had not applied for NHS ethical approval and could not reliably tell whether the respondents worked in the NHS. This left data from n = 277 participants (Table 2). Participants self-reported their professional roles, which were coded by the researchers into 11 categories and also into broad ‘education’ and ‘social care’ categories.

Materials

The survey was split into four sections (see Supplementary materials).

Part 1 comprised 13 items about the participants’ professional background, the frequency with which they worked with parents, with autistic individuals, any autism training they had completed, any personal experience of autism, and their experience and views about asking people whether they had an autism diagnosis.

Part 2 included 29 items assessing their knowledge of autism, adapted from Unigwe et al. (2017). Some items required a ‘true’ or ‘false’ response, for example, ‘A child failing to respond to their name when called can be an early sign of autism’. Other questions had multiple options to choose from with only one being correct, responses marked ‘unsure’ were scored as incorrect. Scores on each item were added to yield a total score of 29. The higher the score, the greater the knowledge about autism. All participants were provided with the correct answers on completion of the survey, along with links to a temporary webpage developed by the primary researcher about autism in mothers, which had been reviewed and approved by the project advisory panel. Two subscales were included: 11 items around ‘Knowledge of Autism in Females’ (Cronbach’s α = 0.67), and 18 items regarding ‘Knowledge of Autism, General’ (Cronbach’s α = 0.49). Given the low internal consistency of the latter subscale, it was excluded from subsequent analyses. Three additional items developed for this study were included in Part 2, focussed on professionals’ attitudes towards autistic parents’ parenting abilities, which were treated separately to the knowledge questions.

Part 3 included four open-ended questions about participants’ experiences of working with autistic parents, e.g. “Can you tell us about any successes or positive experience you have had with working with autistic parents?”

Part 4 was a self-efficacy scale adapted for the current study from Unigwe et al. (2017) designed to understand professionals’ perceived self-efficacy when thinking of working with autistic people, for example, one asked the participants how confident they feel about “Recognising the signs and symptoms of autism in girlsˮ and scores ranging from 1 (‘not at all confident’) to 10 (‘extremely confident’). There were 11 items with potential scores from 10 to 110. Higher scores indicated greater self-efficacy. Where up to 2 items were not completed, the missing item/s were prorated using the mean for the completed items. If more than 2 items were missing, the scale was not computed. High internal consistency (α = 0.91) was found on this scale.

Data analysis

The quantitative data were analysed for frequencies and descriptive information using IBM SPSS. As the distributions for some of the variables (knowledge about autism in women, and self-efficacy scale) were non-normal, therefore non-parametric statistics were used for correlations and group comparisons. The open-ended questions were analysed using qualitative content analysis, following the guidance from Hsieh and Shannon (2005), as we anticipated short answers which would not be sufficiently rich for thematic analysis. A conventional content analysis approach was utilised, where the first author immersed themselves in the data, and using an inductive approach, identified words that expressed key ideas, which were coded. Codes which cohered with others were grouped into sub-categories, and categories with similar content were identified. Credibility was monitored through discussing the coding and category development with the second author.

Study 2 results

Descriptive statistics

As seen in Table 2, of the whole sample, 69% were in contact with autistic adults and/or children every day; 14% at least once a week; 6% less than once a week; and 8% less than once a month. Most participants were in daily contact with parents (64%), while a small percentage reported never having contact with parents (5%). Almost half (43%) of the participants knew autistic people in their personal life and 30% specified that they had one or more autistic family member. No personal experience was reported by 20%. A small number of participants reported themselves to be autistic (3%). The majority of the participants had completed some autism-related training (84%), while some reported being unsure whether they had any autism-related training (4%) and some reported not having any training (12%).

Table 3 details scores on the knowledge of autism in women and the self-efficacy scale. Generally, knowledge of autism in women was good, with a mean close to the maximum for the scale (possible scores were 0–11). By contrast, the self-efficacy mean score was close to the midpoint of the scale (possible scores were 11–110). For the attitudes towards autism in parents questions, very few overtly negative attitudes were endorsed by the participants to the first and second question (Table 3). In the third attitude question, participants were given four statements and asked to indicate which they agreed with most. Of 217 respondents to this question, most professionals (65%) agreed with the statement indicating that autistic mothers at times might need additional support.

How does professional self-efficacy relate to knowledge and experience?

Spearman’s correlations were conducted to examine how self-efficacy related to knowledge of autism. Contrary to prediction, there was no significant correlation between self-efficacy and knowledge, rs = 0.11, p =.09.

Non-parametric group comparisons were conducted to examine whether self-efficacy was higher in those (1) with personal experience of autism (e.g. having experience of autism amongst friends, family, or self, n = 186), versus those without (n = 51), which was found to be the case, U = 5825.5, p <.05; (2) in those who had completed autism training (n = 203) versus those who had not (n = 28), showing that those who had completed training had higher self-efficacy scores, U = 1869 p <.01; and (3) in those who were in education (n = 177) versus social care (n = 60) roles, showing that those in social care roles had higher self-efficacy scores, U = 6295, p <.05.

Open-ended questions

Participants were asked whether they would feel comfortable to ask a woman whether they were autistic and, if the answer was ‘no’, then the participants were prompted to report why not. Just 25% of respondents said that they would ask, 50% said they would not, and 25% were unsure. Reasons not to ask included feeling that it may be offensive, invasive and direct, upsetting to the other person, fearing they may be wrong, and feeling it was the person’s choice to inform them.

Next the categories from the qualitative content analysis on questions related to experiences working with autistic mothers were as follows (Fig. 2):

Positive and rewarding work

Most professionals reported having positive experiences and having a wish to provide good quality care to autistic individuals and autistic parents as it provided them with a sense of satisfaction and reward. The ability to empathise with parents and support them with their challenges left the professionals with a sense of pride and satisfaction. Subcategories were as follows.

Trusting relationships

Professionals shared that through their experience of working with autistic mothers, the absence of ‘trusting relationships’ could be detrimental. The professionals in this study also highlighted that in order to earn the trust of autistic parent/mothers, professionals needed to gain understanding, have time and patience, and be compassionate and open-minded. Some professionals shared that they successfully developed trusting relationships through talking about what the parents might need and providing reassurance, guidance, and timely intervention. “Once relationships are established we have success…Whilst not directly asking if parents have autism, we build trusting relationships so they eventually tell us what we had anticipated. We care for all our families. Many have complex and challenging lives”.

Qualities of autistic parents

This category described some of the contributions made by autistic parents, along with their strengths as parents. They viewed autistic parents as “often very supportive and want the best for their child”. Participants described the strengths of autistic parents, including knowledge about child development, openness and awareness of their own needs and their ability to communicate those needs. “I have worked with a mother who had ASD, she was amazing with her children, one of whom had autism. She was able to relate to their needs and give them the support and care that they needed. Sometimes she would need help, but she was able to care for her children independently (single mother) and she gave them every chance at a happy life”. One professional shared that, where difficulties or misunderstandings arose “it is up to me to adapt the way I work to communicate more effectively” rather than locating the source of difficulty within the autistic mother.

A conflict between needs and resources

Regardless of the encouraging number of adjustments and strategies that professionals used to support autistic parents, there was a clear conflict between knowing that a person-centred approach is required to support autistic parents and having access to the necessary resources to effectively do so. A number talked about the lack of resources, leading to challenges around engagement from parents. “More training is required as children in this day and age should not be being missed in children’s services”. Professionals also mentioned their own time constraints and lack of resources, which led to professionals having to make modifications and go out of their way through their “own good will” which meant that they risked “savage penalties from a target-obsessed system”.

Communication

This category was warranted in its own right, due to the frequency with which participants discussed the communication differences of autistic parents.

Supporting parents with communication challenges

Some participants described their difficulty with the directness of the autistic parents, such as a matter-of-fact style of communication, which could create misunderstandings for professionals and left them feeling they were not liked by the parents. “Early in my career, my feelings were hurt by some comments”. Some professionals recognised that the challenges can be due to their own judgements and expectations, lack of understanding and prejudice. However, for some, the challenges reduced as they gained more experience and they felt more comfortable and able to find helpful ways of supporting autistic individuals. Some professionals attributed communication breakdown to autistic parents’ tendency to fixate on small details, which might be seen as insignificant small details: “They can sometimes be very focused on one aspect of their child’s education or become fixated on something they perceive is or isn’t happening.” This gives insight into possible stereotyping of autistic parents, as well as autistic parents having some challenges around being ‘taken seriously’, which was identified in Study 1.

Examples of good practice

Most professionals wrote about positive experiences and outcomes through taking a tailored approach. One professional advised: “Treat each person as an individual, and respect and acknowledge their views. Never think you know their child better than them. Listen to understand, not to answer or judge.” These led to positive experiences, such as increased social interactions and a parent feeling confident. “I have found that if parents are supported to become confident in their parenting abilities, the outcomes are excellent.” Professionals wrote about employing autism-specific techniques during their meetings with autistic parents to facilitate clear communication between both parties, such as ‘planning and preparation’, allowing enough time, using visual aids, having a trusted staff member with the parent, and trusting parents with information about their child.

Study 2 interim discussion

The findings from Study 2 showed that professionals generally had good knowledge of autism in women, and the vast majority expressed positive attitudes towards autism in mothers. Nevertheless, professional self-efficacy was not particularly high. The analyses supported the idea that professional self-efficacy was higher in those who had attended training, had personal experience of autism, and were in social care versus education professionals, but was unrelated to knowledge of autism. Analysis of the open-ended questions revealed themes which overlapped substantially with themes raised by autistic mothers in Study 1. The general discussion below explores common themes.

General discussion

This two-study paper provides insight into both the experience of autistic mothers and the professionals who work with them. Study 1 highlighted a range of strengths and challenges that autistic mothers face in their roles (see Study 1 interim discussion), one of which was difficulty interacting with professionals. The co-produced survey of professionals’ experience of interacting with autistic mothers in Study 2 gave important and complimentary insights into these exchanges.

Study 2 yielded a number of positive findings. There was high uptake of autism training, which contrasts with previous studies within the UK (Dillenberger et al., 2016). Knowledge of autism was high amongst participants, and self-expressed attitudes towards autism in parents were overwhelmingly positive. This is a welcome counterpoint to the perception that there is stigma towards autism amongst professionals (Botha et al., 2020). Of course, the study is limited by using self-report and a self-selecting sample, and an element of social desirability bias may have influenced the responses. Those working in social care rated themselves as having higher self-efficacy than those in education, which may point to a need for further training for school and University staff on adult autism. Furthermore, those who had completed autism training rated themselves as having higher self-efficacy, potentially showing the benefits of training on practice, as has been found with physicians (Clarke & Fung, 2022).

The qualitative content analysis of education and social care professionals’ experience mirrored themes from Study 1 in fascinating ways. The autistic mothers described ways they approached meetings with professionals, including researching in advance and coming prepared with information; strongly advocating for their children irrespective of what others think; and they described feeling judged and misunderstood at times. In Study 2, some professionals mentioned these features explicitly, describing the feeling that autistic parents could be highly informed and may have had set ideas about the outcome of a meeting, or sometimes appeared to be fixated on a particular outcome. Professionals admitted to sometimes struggling with the direct style of communication and feeling that autistic parents did not like them. This provides a vivid illustration of the double empathy problem (Milton, 2012; Mitchell et al., 2021). The findings suggest that the mutual challenges experienced by the mothers and the professionals may arise from misunderstanding between the two groups. Professionals may at times interpret the parents’ direct communication style as challenging or offensive and may become defensive in response. In turn, autistic parents described ‘not caring what others think’, particularly when advocating for their children. As such, it is possible that they may at times have difficulty with understanding how they are perceived by the professionals, or in tuning into the priorities and viewpoints of the professionals. Adding to this the experience of having their parenting judged negatively, it is no wonder if autistic mothers may in turn be defensive or mistrustful during interactions. Compounding the difficulties in these interpersonal exchanges is the often-unnamed autism. Only a quarter of professionals reported that they would ask a parent if they were autistic, for fear of being perceived as rude or intrusive. In turn, autistic mothers described fearing stigma if they revealed their diagnoses. This is likely to lead to scenarios in which open communication is inhibited.

Previous research has supported the idea that a mismatch of styles and expectations between autistic and neurotypical people is what leads to communication difficulties (e.g. Crompton et al., 2020), in other words, misunderstandings can be bidirectional (Pager & Shepherd, 2008; Milton, 2012). Research with dyads of autistic women and professionals would be highly beneficial to examine the sources of communication success and challenge, and to better understand interpersonal transactions and the interpretations of both parties. Recent research has begun to utilise these methodologies in dyadic work (e.g. Gordon-Pershey & Hodge, 2018; Heasman & Gillespie, 2019; Sasson & Morrison, 2019) and with mixed focus groups between professionals and patients (e.g. Femdal & Solbjør, 2018).

The constraints of time and resources were also noted to limit the capacity of professionals to provide autistic parents with the adaptations they needed, even where they understood what those were. On the other hand, professionals in the study shared that when they made appropriate adjustments to their practice, they experienced rewarding work with autistic parents. In the current study, autistic mothers also reported some of their experiences with professionals to be positive. These results highlight that simple adaptations, such as consistency of care, taking time to build relationships, using visual aids, giving clear written information, and working collaboratively, can have a significant impact. Assuming competence in autistic mothers and taking a flexible attitude towards achieving outcomes appeared to characterise the more effective approaches by professionals.

Strengths of the current studies include the participatory research design, prioritising inclusivity of the views of autistic mothers in design, data collection and interpretation, in keeping with a commitment to the neurodiversity movement (Fletcher-Watson et al., 2019). The study also provided psychoeducation around autism in mothers to professionals who participated in Study 2, demonstrating a commitment to Kurt Lewin’s philosophy of ‘action research’ (Adelman, 1993). The mixed-method approach of Study 2 also provided valuable insights into both the extent and prevalence of knowledge, self-efficacy and attitudes, as well as evoking the reasons and rationale behind these measures. Of course, both studies are limited by the self-selecting samples: in Study 1, this may mean that mothers experiencing fewer stressors were able to participate; in Study 2, this may mean that professionals who were well disposed to working with autistic populations were more likely to respond. Nevertheless, the studies provided valuable insight on autistic motherhood from mothers’ and professionals’ perspectives, and indicated some interesting areas for further research.

The two studies presented here suggest that supporting professionals to understand autistic women and mothers should be as much a priority as helping mothers to communicate their own needs. Initiatives may be most helpfully focussed on increasing the confidence of professionals and autistic women in communicating with each other. Autistic-led training may be a useful way to facilitate this (e.g. Gillespie-Lynch et al., 2021), and may lead to increases in confidence in both autistic parents and professionals.

Data availability

The quantitative data from Study 2 has been submitted as a supplemental file.

Change history

14 June 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06112-3

Notes

Throughout this paper, the terms women, girls, and mother are used rather than ‘female’, and boys or men rather than ‘male’, in recognition of the social construction of gender. Research on the biological aspects of pregnancy and childbirth is included, though these experiences will not apply to all of those who identify as autistic women and mothers, e.g. transgender, adoptive, or stepmothers.

References

Adelman, C. (1993). Kurt Lewin and the origins of Action Research. Educational Action Research, 1(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965079930010102

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author.

Ashworth, M., Crane, L., Steward, R., Bovis, M., & Pellicano, E. (2021). Toward empathetic Autism Research: Developing an autism-specific Research Passport. Autism in Adulthood, 3(3), 280–288. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0026.

Autism Act. (2009). Retrieved online [16 April 2024] at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2009/15/contents

Aylott, J. (2010). Improving access to health and social care for people with autism. British Journal of Nursing, 24(27), 47–56.

Baranek, G. T. (2002). Efficacy of sensory and motor interventions for children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32(5), 397–422. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020541906063

Bargiela, S., Steward, R., & Mandy, W. (2016). The experiences of late-diagnosed women with autism spectrum conditions: An investigation of the female autism phenotype. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(10), 3281–3294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2872-8

Botha, M., Dibb, B., & Frost, D. M. (2020). Autism is me: An investigation of how autistic individuals make sense of autism and stigma. Disability & Society, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1822782

Bradley, L., Shaw, R., Baron-Cohen, S., & Cassidy, S. (2021). Autistic adults’ experiences of camouflaging and its perceived impact on mental health. Autism in Adulthood. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0071

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2020). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020

Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Rance, N. (2014). How to use thematic analysis with interview data (process research). In A. Vossler, & N. Moller (Eds.), The Counselling & Psychotherapy Research Handbook. Sage.

Burton, T. (2016). Exploring the experiences of pregnancy, birth and parenting of mothers with autism spectrum disorder. Keele University. https://eprints.staffs.ac.uk/2636/1/. Accessed 16 Apr 2024.

Chapman, R. (2021). Neurodiversity and the social ecology of mental functions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(6), 1360–1372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620959833

Clarke, L., & Fung, L. K. (2022). The impact of autism-related training programs on physician knowledge, self-efficacy, and practice behavior: A systematic review. Autism, 26(7), 1626–1640. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221102016

Crompton, C. J., Hallett, S., Ropar, D., Flynn, E., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2020). I never realised everybody felt as happy as I do when I am around autistic people’: A thematic analysis of autistic adults’ relationships with autistic and neurotypical friends and family. Autism, 24(6), 1438–1448. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320908976

Crompton, C. J., Hallett, S., McAuliffe, C., Stanfield, A. C., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2022). A Group of Fellow travellers who understand: Interviews with autistic people about post-diagnostic peer support in Adulthood. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 831628. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.831628

Department of Health. (2014). Think autism: Fulfilling and rewarding lives, the strategy for adults with autism in England: An update. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/299866/Autism_Strategy.pdf. Accessed 16 Apr 2024.

Dillenburger, K., McKerr, L., Jordan, J. A., & Keenan, M. (2016). Staff Training in Autism: The one-Eyed wo/man. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(7), 716.

Donovan, J. (2020). Childbirth experiences of women with Autism Spectrum Disorder in an Acute Care setting. Nursing for Women’s Health, 24(3), 165–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nwh.2020.04.001

Dugdale, A. S., Thompson, A. R., Leedham, A., Beail, N., & Freeth, M. (2021). Intense connection and love: The experiences of autistic mothers. Autism, 25(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/13623

Femdal, I., & Solbjør, M. (2018). Equality and differences: Group interaction in mixed focus groups of users and professionals discussing power. Society Health & Vulnerability, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/20021518.2018.1447193

Fletcher-Watson, S., Adams, J., Brook, K., Charman, T., Crane, L., Cusack, J., Leekam, S., Milton, D., Parr, J. R., & Pellicano, E. (2019). Making the future together: Shaping autism research through meaningful participation. Autism, 23(4), 943–953. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318786721

Gardner, M., Suplee, P. D., Bloch, J., & Lecks, K. (2016). Exploratory study of childbearing experiences of women with Asperger syndrome. Nursing for Women’s Health, 20(1), 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nwh.2015.12.001

Giarelli, E., Wiggins, L. D., Rice, C. E., Levy, S. E., Kirby, R. S., Pinto-Martin, J., & Mandell, D. (2010). Sex differences in the evaluation and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders among children. Disability and Health Journal, 3(2), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.07.001

Gillespie-Lynch, K., Daou, N., Obeid, R., et al. (2021). What contributes to Stigma towards Autistic University Students and students with other diagnoses? Journal of Autism Development Disorder, 51, 459–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04556-7

Gordon-Pershey, M., & Hodge, A. (2018). Communicative behaviors of sibling dyads with a child with autism and a typically developing child. Journal of Interactional Research in Communication Disorders, 8(2), 246–242.

Gould, J., & Ashton-Smith, J. (2011). Missed diagnosis or misdiagnosis? Girls and women on the autism spectrum. Good Autism Practice (GAP), 12(1), 34–41.

Grant, L. (2015). From here to maternity: Pregnancy and motherhood on the autism spectrum. Jessica Kingsley.

Griffiths, S., Allison, C., Kenny, R., Holt, R., Smith, P., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2019). The vulnerability experiences quotient (VEQ): A study of vulnerability, mental health and life satisfaction in autistic adults. Autism Research, 12(10), 1516–1528. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2162

Halladay, A. K., Bishop, S., Constantino, J. N., Daniels, A. M., Koenig, K., Palmer, K., Messinger, D., Pelphrey, K., Sanders, S. J., Singer, A. T., Taylor, J. L., & Szatmari, P. (2015). Sex and gender differences in autism spectrum disorder: Summarizing evidence gaps and identifying emerging areas of priority. Molecular Autism, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-015-0019-y

Hampton, S., Allison, C., Aydin, E., Baron-Cohen, S., & Holt, R. (2022a). Autistic mothers’ perinatal well-being and parenting styles. Autism, 26(7), 1805–1820. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211065544

Hampton, S., Man, J., Allison, C., Aydin, E., Baron-Cohen, S., & Holt, R. (2022b). A qualitative exploration of autistic mothers’ experiences II: Childbirth and postnatal experiences. Autism, 26(5), 1165–1175. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211043701

Hansen, T. (2012). Parenthood and happiness: A review of folk theories versus empirical evidence. Social Indicators Research, 108(1), 29–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205

Happé, F., & Frith, U. (2020). Annual Research Review: Looking back to look forward– changes in the concept of autism and implications for future research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(3), 218–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13176

Hayes, S. A., & Watson, S. L. (2013). The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(3), 629–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1604-y

Head, A. M., McGillivray, J. A., & Stokes, M. A. (2014). Gender differences in emotionality and sociability in children with autism spectrum disorders. Molecular Autism, 5(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/2040-2392-5-19

Heasman, B., & Gillespie, A. (2019). Neurodivergent intersubjectivity: Distinctive features of how autistic people create shared understanding. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 23(4), 910–921. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318785172

Higgins, J. M., Arnold, S. R., Weise, J., Pellicano, E., & Trollor, J. N. (2021). Defining autistic burnout through experts by lived experience: Grounded Delphi method investigating. Autistic Burnout Autism. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613211019858

Hiller, R. M., Young, R. L., & Weber, N. (2014). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder based on DSM-5 criteria: Evidence from clinician and teacher reporting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(8), 1381–1393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9881-x

Hsieh, H-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Hull, L., Petrides, K. V., & Mandy, W. (2020). The female autism phenotype and camouflaging: A narrative review. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 7(4), 306–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-020-00197-9

Jenkinson, R., Milne, E., & Thompson, A. (2020). The relationship between intolerance of uncertainty and anxiety in autism: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Autism, 24(8), 1933–1944. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320932437

Lai, M.-C., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2015). Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 2(11), 1013–1027. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00277-1

Lai, M. C., Baron-Cohen, S., & Buxbaum, J. D. (2015). Understanding autism in the light of sex/gender. Molecular Autism, 6(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-015-0021-4

Lai, M. C., Kassee, C., Besney, R., Bonato, S., Hull, L., Mandy, W., Szatmari, P., & Ameis, S. H. (2019). Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(10), 819–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30289-5

Lau, W. Y. P., Peterson, C. C., Attwood, T., Garnett, M. S., & Kelly, A. B. (2016). Parents on the autism continuum: Links with parenting efficacy. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 26, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2016.02.007

Lewis, C. C., Mettert, K., & Lyon, A. R. (2021). Determining the influence of intervention characteristics on implementation success requires reliable and valid measures: Results from a systematic review. Implementation Research and Practice, 2. https://doi.org/10.1177/2633489521994197

Lum, M., Garnett, M., & O’Connor, E. (2014). Health communication: A pilot study comparing perceptions of women with and without high functioning autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(12), 1713–1721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.09.009

Luyten, P., Nijssens, L., Fonagy, P., & Mayes, L. C. (2017). Parental reflective functioning: Theory, Research, and clinical applications. The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 70(1), 174–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/00797308.2016.1277901

Mandy, W., Chilvers, R., Chowdhury, U., Salter, G., Seigal, A., & Skuse, D. (2012). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder: Evidence from a large sample of children and adolescents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(7), 1304–1313. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21947663/

Mason, D., Ingham, B., Unrbanowicz, A., Michael, C., Birtles, H., Woodbury-Smith, M., Brown, T., James, I., Scarlett, C., Nicolaidis, C., & Parr, J. P. (2019). A systematic review of what barriers and facilitators prevent and enable physical healthcare services access for autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49, 3387–3400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04049-2

McDonnell, C., & DeLucia, E. A. (2021). Pregnancy and parenthood among autistic adults: Implications for advancing maternal health and parental well-being. Autism in Adulthood, 100–115. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0046

Milner, V., McIntosh, H., Colvert, E., & Happé, F. (2019). A qualitative exploration of the female experience of autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(6), 2389–2402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03906-4

Milton, D. E. M. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: The ‘double empathy problem. ’ Disability & Society, 27(6), 883–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.710008

Mitchell, P., Sheppard, E., & Cassidy, S. (2021). Autism and the double empathy problem: Implications for development and mental health. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 39(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjdp.12350

Mockford, C., Staniszewska, S., Griffiths, F., & Herron-Marx, S. (2012). The impact of patient and public involvement on UK NHS health care: A systematic review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 24(1), 28.

Moseley, R. L., Gregory, N. J., Smith, P., Allison, C., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2019). A choice, an addiction, a way out of the lost: Exploring self-injury in autistic people without intellectual disability. Molecular Autism, 10, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-019-0267-3

Pager, D., & Shepherd, H. (2008). The sociology of discrimination: Racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit, and consumer markets. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 181–209. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131740

Pellicano, E., & den Houting, J. (2021). Annual research review: Shifting from ‘normal science’ to neurodiversity in autism science. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 63, 381–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13534

Pellicano, E., Dinsmore, A., & Charman, T. (2014). What should autism research focus upon? Community views and priorities from the United Kingdom. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 18(7), 756–770. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314529627

Pohl, A. L., Crockford, S. K., & Blakemore, M. (2020). A comparative study of autistic and non-autistic women’s experience of motherhood. Molecular Autism, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-019-0304-2

Radev, S., Freeth, M., & Thompson, A. R. (2023). I’m not just being difficult… I’m finding it difficult’: A qualitative approach to understanding experiences of autistic parents when interacting with statutory services regarding their autistic child. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613231212794

Rodgers, J., Herrema, R., Honey, E., & Freeston, M. (2018). Towards a treatment for intolerance of uncertainty for autistic adults: A single case experimental design study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(8), 2832–2845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-3550-9

Rogers, C., Lepherd, L., Ganguly, R., & Jacob-Rogers, S. (2017). Perinatal issues for women with high functioning autism spectrum disorder. Women and Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 30(2), e89–e95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2016.09.009

Saha, A., & Agarwal, N. (2016). Modeling social support in autism community on social media. Network Modeling Analysis in Health Informatics and Bioinformatics, 5(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13721-016-0115-8

Samuel, P., Yew, R. Y., Hooley, M., Hickey, M., & Stokes, M. A. (2022). Sensory challenges experienced by autistic women during pregnancy and childbirth: A systematic review. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 305(2), 299–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-021-06109-4

Sasson, N. J., & Morrison, K. E. (2019). First impressions of adults with autism improve with diagnostic disclosure and increased autism knowledge of peers. Autism, 23(1), 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361317729526

Sedgewick, F., Hill, V., Yates, R., Pickering, L., & Pellicano, E. (2016). Gender differences in the social motivation and friendship experiences of autistic and non-autistic adolescents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46, 1297–1306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015

Simone, R. (2010). Aspergirls: Empowering females with Asperger Syndrome. Jessica Kingsley Publishers Ltd.

Sinclair, J. (2012). Autism network international: The development of a community and its culture. In J. Bascom (Ed.), Loud hands: Autistic people, speaking (pp. 17–48). The Autistic.

Suplee, P., Gardner, M., Bloch, J., & Lecks, K. (2014). Childbearing experiences of Women with Asperger Syndrome. Journal of Obstetric Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 43(S1), S76–S76. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12455

Talcer, M. C., Duffy, O., & Pedlow, K. (2021). A qualitative exploration into the sensory experiences of autistic mothers. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 53, 834–849. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05188-1

Tint, A., Weiss, J. A., & Lunsky, Y. (2017). Identifying the clinical needs and patterns of health service use of adolescent girls and women with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research: Official Journal of the International Society for Autism Research, 10(9), 1558–1566. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1806

Unigwe, S., Buckley, C., Crane, L., Kenny, L., Remington, A., & Pellicano, E. (2017). GPs’ confidence in caring for their patients on the autism spectrum: An online self-report study. British Journal of General Practice, 67(659). https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp17X690449

Venkat, A., Jauch, E., Russell, W. S., Crist, C. R., & Farrell, R. (2012). Care of the patient with an autism spectrum disorder by the general physician. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 88(1042), 472–481. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2011-130727

Viswanathan, M., Ammerman, A., Eng, E., Garlehner, G., Lohr, K. N., Griffith, D., Rhodes, S., Samuel-Hodge, C., Maty, S., Lux, L., Webb, L., Sutton, S. F., Swinson, T., Jackman, A., & Whitener, L. (2004). Community-based participatory research: Assessing the evidence. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment (Summary), 99, 1–8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15460504/

Warrier, V., Greenburg, D. M., Weir, E., Buckingham, C., Smith, P., Lai, M. C., Allison, C., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2020). Elevated rates of autism, other neurodevelopmental and psychiatric diagnoses, and autistic traits in transgender and gender-diverse individuals. Nature Communications, 11, 3959. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17794-1

Webster, J., Linnane, J. W., Dibley, L. M., & Pritchard, M. (2000). Improving antenatal recognition of women at risk for postnatal depression. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 40(4), 409–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1479-828X.2000.tb01170.x

Wood, D., Crapnell, T., Lau, L., Bennett, A., Lotstein, D., Ferris, M., & Kuo, A. (2018). Emerging adulthood as a critical stage in the life course. In N. Halfon, C. B. Forrest, R. M. Lerner, & E. M. Faustman (Eds.), Handbook of life course health development. Springer. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK543712/. Accessed 16 Apr 2024.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by departmental seed funding from York St John University and University College Cork, awarded to the second author. The authors wish to particularly thank the members of the autistic mothers’ project advisory panel who provided invaluable input on the research topic, design, and interpretation. We also thank the participants who took part in the study, and the gatekeepers who distributed the survey.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The research was carried out as part of the first author’s doctoral thesis in Counselling Psychology under the supervision of the second and third authors. The second author drafted and re-drafted the manuscript, while the first and third authors provided comments and corrections. All authors approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the University ethics board and all testing was in line with BPS and APA standards. Informed consent to participate was obtained, and for data to be published.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original version of this article has been revised to correct the article title.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

(DOCX 31 kb)

Supplementary Material 2

(SAV 888 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sutcliffe-Khan, F., Larkin, F. & Hamilton, L. Parents’ and professionals’ views on autistic motherhood using a participatory research design. Curr Psychol 43, 21792–21807 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05999-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05999-2