Abstract

Since the seminal work by Hackman and Oldham (1975) there has been a growing body of literature demonstrating how work characteristics can positively both organizations and their employees. While the very nature of the task or job at hand is well explored, insufficient attention has been given to the social and cultural context in which the work is done (Spreitzer & Cameron, 2012). Based on Meynhardt’s public value approach (2009, 2015), we investigate whether organizational public value acts as an additional work characteristic in the Job Characteristics Model (JCM), thus extending the model. Specifically, we theorize that organizational public value is an additional unique resource for employees and social context work characteristic in the JCM that is positively related to employees work engagement. Additionally, our study analyzes that the positive relationship between the work characteristics, including organizational public value, and work engagement is mediated by self-efficacy. Moreover, we analyze whether employees working in industries with a public focus integrated into their core business will experience higher levels of public value in their jobs than employees in other industries. To test our hypotheses, we conducted a representative online survey in different public and non-public organizations in Switzerland (N = 949). Overall, the results support our hypotheses and contribute to close the gap by taking social context factors into the JCM and to reveal processes between the macro-level (organizational public value, work characteristics) and micro-level (employees work experience). Further theoretical and practical implications as well as future research avenues are discussed in the paper.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

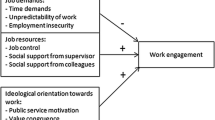

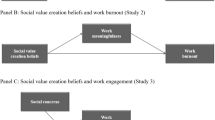

What makes individuals, workgroups and organizations flourish at work is an important topic that has attracted increasing interest from researchers. To find out more about how positive states at work emerge, positive organizational scholarship researchers have called for further research that addresses the interrelationships among individuals and the broader organization as well as the social and cultural context of work (Dutton & Glynn, 2008; Spreitzer & Cameron, 2012). Moreover, this relationship receives more public attention due to issues such as ecological, demographical or geopolitical grand challenges (Brammer et al., 2019). Due to the rising number of global events, business needs to step up on societal issues. Because public and non-public organizations contribute to societal cohesion (Meynhardt, 2015), societal legitimization of organizational activities remains a critical point. Thus, scholars and practitioners are focusing on the relationship between organizations, society and individuals, pursuing concepts such as public value (Meynhardt, 2009, 2015). The public value approach of Meynhardt (2009, 2015) describes the individual perception of an organization’s contribution to the common good, so that the evaluation can be positive or negative, depending on the shared collective need fulfilment. Already Bryson et al. (2021) emphasized, “[t]o create public value and advance the common good is […] what the grand challenges of our time require” (p. 180). In particular, current data highlights that existing crisis and challenges have a negative impact on employees work outcomes (Newman et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2021). Therefore, organizations are being called upon to find ways to counteract this (Gabriel & Aguinis, 2022; Pearson & Mitroff, 2019). One pathway begins with the recognition that the social context in which organizations are embedded, has an impact on the organizational and individual level and should be considered in the work design. However, current work design models neglect the social impact of organizations for employees and society and the effect on positive work outcomes, such as work engagement (Bailey et al., 2017). Established models, such as the job characteristics model (JCM) (Hackman & Oldham, 1975), addresses questions of how tasks need to be designed to positively influence employee-related outcomes through related work characteristics, but the broader social and organizational context has barely been taken into account, so there is a need to expand the JCM. Previous studies have mainly focused on the relationship of work characteristics such as skill variety or task identity on positive work outcomes (Milovanska-Farrington, 2023; Rai & Maheshwari, 2020; Saks, 2006). Consequently, we need more research into the relevance of work characteristics, not only in terms of the task itself (Parker et al., 2001), but rather in terms of the social context of the organization and the associated impact on employees’ work outcomes. In this regard, our main aim of the study is to include public value as an organizational social context factor and additional unique work characteristic into the JCM to investigate the relationship with positive work-related outcomes, especially on employees work engagement. In order to close the gap between the macro-level (organizational public value, work characteristics) and micro-level (employees work experience), it is important to understand the underlying processes. While organizations are stronger called upon to reflect their purpose and role in society, at the same time, employees search for purpose and meaning in work (Jasinenko & Steuber, 2023; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Experiencing work meaningfulness is one of the most important factor related to organizational outcomes such as employee well-being or work engagement (e.g., Albrecht et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2011; Lysova et al., 2019; Panda et al., 2022). Thus, understanding alternative sources of meaning and motivation at work, which are associated with human thriving and contribution to the greater good, is central for work researchers. Following the meaningfulness of work that arises from the underlying mechanisms of the JCM and public value theory, we further include self-efficacy beliefs as mediator of this connection. Thus, our study connects to the work of Grant (2008), who found that when employees see the significance of their work by improving the welfare of others, it positively influences their job performance. By extending these findings to the organizational level instead of the task level, we assume that when employees recognize their organization contributes to the greater good, it enables them to perceive their work as more meaningful and strengthens also their self-efficacy, which should be positively related to their work engagement. So far, the purposeful strategic focus on creating public value has already been linked to increased organizational performance at the macro-level (Gartenberg et al., 2019), but the outcomes of perceived public value creation at the intra-individual micro-level have not yet been sufficiently researched (Hartley et al., 2017). We also seek to examine whether there is a difference in the perception of the public value of public and non-public organizations. Ritz et al. (2023) have already pointed out to closing this research gap by encouraging future research to examine the extent to which perceptions of public value depend on sector affiliation and other organizational characteristics. For the purpose of our study, we applied a cross-sectional design with study data from different industries in public and non-public organizations in Switzerland.

With this paper, we contribute three-fold: First, we supplement the JCM with Meynhardt’s public value approach (2009, 2015), which considers the contribution to the common good as social contextual factor at the macro-level and investigate the relationship with micro-level experience of employee work engagement. In this context the organizational, societal and individual levels are considered in our study. Second, our study serves as a further addition to the field of research on public value (Grubert et al., 2022; Meynhardt & Jasinenko, 2020; Ritz et al., 2023) that has also supported to bridge the gap between micro- and macro-level processes. Third, our study shows practitioners what positive consequences organizational public value has on employees beside other work characteristics, so that measures to create public value within the organization should be established.

Theoretical background and hypotheses development

Job characteristics model

Work design research can be described as “the study, creation, and modification of the composition, content, structure, and environment within which jobs and roles are enacted” (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2008, p. 47). In the following, we employ the term work design rather than job design because this term better reflects the fact that important aspects of work include characteristics of the environment in which work takes place in addition to the content and organization of tasks (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006). The JCM proposes five core dimensions of work – skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy and feedback from the job (Hackman & Oldham, 1975). These characteristics produce three “critical psychological states”, namely experienced meaningfulness of work, experienced responsibility for the outcomes of work, and knowledge of the results of work activities (Hackman & Oldham, 1975). These psychological states are considered to be responsible for positive personal and work outcomes such as internal motivation, work satisfaction, or performance (Hackman & Oldham, 1975). Working in jobs with high task significance leads employees to feel that their job is meaningful (Hackman & Oldham, 1975). However, by focusing on the task level, task significance signals the employee that their own endeavors provide opportunities to contribute to others’ welfare (Grant, 2008). Task significance does not refer to contributing to others’ welfare at an organizational level, which is considered in our study. Some studies support the importance of social characteristics in work design (e.g., Humphrey et al., 2007; Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006). Results of the analysis showed that social characteristics explained a large amount of unique variance concerning different employee outcomes like organizational commitment (40%), job satisfaction (17%) and subjective performance (9%) apart from motivational characteristics (Humphrey et al., 2007). However, just a few researchers have addressed social and contextual factors of work. Morgeson and Humphrey (2006), for example, developed an extended model of work design that considers social characteristics (e.g., social support and feedback from superiors and employees) and contextual characteristics (e.g., ergonomics and work conditions). Grant (2007) took another important step toward a broader social perspective on work design, developing a conceptual framework to explain relational aspects of work design. He proposed that a relational architecture of jobs can enhance employees’ prosocial motivation and performance (Grant, 2007). Although these approaches extend the view on work design models toward emphasizing social and contextual factors of work, they do not consider the broad view of how organizations are embedded in society and how the current grand challenges affect the organizational and employee level in this context. Therefore, we address the question of the relevance of an organization’s public value as an addition in the JCM for employees work engagement.

Public value

Organizations are “organs of society. They do not exist for their own sake, but to fulfill a specific social purpose and satisfy a specific need of society, community, or individual” (Drucker, 2011, p. 36). Since organizations work in and for society, they have an important role in shaping societal values that are collectively shared (Meynhardt, 2009, 2015). Organizations behave responsibly when corporate actions are aligned with society’s values and needs and are legitimized by society (Meynhardt, 2009, 2015). One needs to look at its micro foundation to understand better the consequences of socially responsible firm behavior for employees. In this context, the construct of organizational public value is used to identify the value contribution of an organization to society. Based on Meynhardt’s approach (2009, 2015), the theory includes a psychologically-based explanation for the relationship between individual experiences and the evaluation of business activities to improve the greater good. Public value refers to the interrelatedness between the individual and society and links individual basic needs to societal value creation of organizations. According to Meynhardt’s approach, “value for the public is a result of evaluations about how basic needs of individuals, groups and the society as a whole are influenced in relationships involving the public” (Meynhardt, 2009, p. 212). Thereby, emotional-motivational processes like needs, emotions, or attitudes that initiate evaluations build the basis of evaluation (Meynhardt, 2009). Further, psychological needs build the basis of public value because every evaluation is grounded in psychological needs, which serve as reference points for evaluations (Meynhardt, 2009, 2015). This evaluation of organizational activities is calibrated according to these basic psychological needs, which have their foundation in Epstein’s cognitive-experiential self-theory (Epstein, 2003): the need for orientation and control, which reflects a utilitarian-instrumental dimension; the need for positive self-evaluation, which reflects a moral-ethical dimension; the need for positive relationships, which reflects a political-social dimension; and the need for gaining pleasure and avoiding pain, which reflects a hedonistic-aesthetical dimension (Meynhardt, 2009). Hence, organizations can contribute to the fulfillment of basic needs and, in this way, can create public value but can also destroy public value if basic needs are not satisfied (Meynhardt, 2009, 2015). Public value integrates different equally important value dimensions and thus takes a more holistic view on value creation. We grounded our study on the public value approach by Meynhardt (2009, 2015). Especially, value creation for society can be seen as a resource for the individual (Meynhardt, 2009), because the satisfaction of needs is a condition for personal development (Epstein, 2003). It responds to the needs of individuals to find meaning and purpose in life. Previous research findings has shown a positive relationship between organizational public value and motivational work outcomes at the organizational and employee level (Grubert et al., 2022; Ritz et al., 2023). Accordingly, the current research results lead to the assumption that organizational public value is an important social context work characteristic at the organizational level that is positively related to work engagement at the individual level. In this regard, Meynhardt’s public value approach (2009, 2015) provides an organizational perspective and allows us to integrate processes between the macro- and micro-level.

The relationship between work characteristics, including organizational public value, and work engagement

Our model aims to create understanding about the relationship between work characteristics, including the employee perception of an organizational public value, and employee work engagement and their underlying mechanism. In the recent years, the work engagement concept and research field gained interest. The authors Schaufeli et al. (2002) describe the experience of engagement among employees as a positive work-related state of mind with character traits of vigour, dedication and absorption. A majority of work engagement research focuses on the impact at the individual factors instead of situational and contextual factors (Bailey et al., 2017). Thus, previous research has been undertaken by work design research, which has shown that good working conditions and workplace lead to higher levels of work engagement (Dinh, 2020; Rasool et al., 2021; Jurek & Besta, 2021; Truss et al., 2013). In the context of the JCM, a meta-analyze pointed out that task-related work characteristics (task variety and autonomy) are positively linked to engagement at work (Crawford et al., 2010). Further research has indicated that work characteristics are positively related to work engagement (e.g., Hakanen et al., 2008; Rai & Maheshwari, 2020; Saks, 2006). But the field has broadened through additional research examining not only work-specific characteristics (Chen et al., 2011) as in the JCM, but also contextual characteristics related to work engagement (Bailey et al., 2017; Christian et al., 2011; Humphrey et al., 2007). However, so far, there is no research that take social context characteristics as the public value into consideration. In this sense, this study attempts to identify the positive relationship of the organizational and societal level on work engagement on the individual level in order to bridge the gap, which was already postulated by Bailey et al. (2017). This is becoming increasingly important due to the current challenges organizations are confronted with (Brammer et al., 2019). We extended the JCM by the inclusion of the employee perception of organizational public value, which leads to our argument that an organization’s contribution to society is a source of meaningfulness for employees and an important additional work characteristic in the JCM, which has not been researched before according to our knowledge. Many employees are searching for more than mere financial compensation and want to find work that offers the possibility to achieve something meaningful. Hence, work design models should integrate alternative manifestations of work meaningfulness that are not limited to the characteristics of certain tasks (Chaudhary, 2022; Glavas, 2012). One source of meaningfulness for the employee should be represented by the organization’s contribution to the common good in the sense of public value. In this study the term meaningfulness is defined as the perception of the importance of goals and activities they perform in the organizations in relation to employees own self and life (Barrick et al., 2013). In order to provide employees with meaningfulness, organizations have a responsibility to balance the needs of the organization with the needs of the employees (Cartwright & Holmes, 2006). Organizations that contribute to the common good can satisfy the basic needs of employees, as described in Meynhardt’s public value theory (2009, 2015), which leads to employees valuing their work as more meaningful, rewarding and worthwhile for themselves and others (Aguinis & Glavas, 2019; May et al., 2004). Accordingly, work meaning arises when employees understand what they are doing and why their work is significant (Wrzesniewski et al., 2003). In this view, work meaning is socially constructed and dynamic over time. Individual characteristics like personal values and preferences, along with the social context – the interaction with others – contribute appreciably to work meaning (Wrzesniewski et al., 2003). Work meaning at the individual task level focuses on the content of the work itself, whereas work meaning at the organizational level focuses on the interaction between organizational members and the values and goals of the organization (Pratt & Ashfort, 2003). Since meaningfulness depends on employees’ identities and individual sense-making, it cannot just be provided by the organization. However, organizations can facilitate employees’ experiences of meaningfulness in and at work (Pratt & Ashfort, 2003). Organizational practices that concentrate on the job itself, such as job redesign to increase skill variety or autonomy, foster the experience of meaningfulness in work. The experience of meaningfulness at work can be achieved by enriching employees’ organizational membership by promoting organizational goals, values, or beliefs or the alteration of relationships between employees (Pratt & Ashfort, 2003). Employees’ perception of work as meaningful has a positive impact on work outcomes (Albrecht et al., 2021; Allan et al., 2019; Frieder et al., 2018; Hackman & Oldham, 1975; Lysova et al., 2019; Panda et al., 2022), especially on work engagement (Woods & Sofat, 2013; Demirtas et al., 2017; Fairlie, 2011). Particularly important is the research on work engagement that has identified an indirect relationship between work characteristics and work engagement through meaningfulness (May et al., 2004; Rothmann & Welsh, 2013). Consequently, it is not surprising that meaningful work characteristics – in the sense of self-actualizing work, work that has a social impact, reflects values and realizes one’s life goals – were found to predict substantive variance of employee engagement in addition to other work characteristics (e.g., Fairlie, 2011). Other studies have shown that the experience of work meaningfulness has been the most powerful mediator between all motivational work characteristics and work outcomes (Humphrey et al., 2007). Hence, we argue that in the same way task-specific work characteristics contributes to experienced meaningfulness in work, public value should contribute to experienced meaningfulness at work. Therefore, we believe that the organization’s value creation for society offers an additional resource for the employee (Meynhardt, 2015) by infusing meaningfulness at work and thus should be positively related to employee work engagement. Thus, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

Employee perception of an organization’s public value accounts for additional unique variance in employee work engagement beyond the work characteristics skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy and feedback from the job.

The mediating role of self-efficacy in the relationship between work characteristics, including organizational public value, and work engagement

In addition to work characteristics and organizational public value as a resource for the employee work engagement, individual factors are also important to consider, because they play an important role in work design models owing to their interaction with work characteristics (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Individual factors might act as “third variables” (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014, p. 51) in the sense that they not only influence how work characteristics are perceived, but also influence employee well-being and motivation. According to the conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll, 1989), individuals strive to gain, build and preserve resources as well as experience stress when resources are threatened. A key resource that relates to physical and emotional well-being, and which is important for human functioning as a personal resource, is self-efficacy (Bandura, 1994; Hobfoll, 1989; Judge et al., 2007). The self-efficacy theory is based on Bandura’s conception (1997) and describes individuals’ assessment of how effectively they can organize and perform the cognitive, social and behavioral skills that constitute them in dealing with future situations (Bandura, 1997, 1983). The belief that one’s skills are sufficient in a situation arises from successful past experiences, vicarious learning, verbal persuasion, and physiological and psychological states (Bandura, 1997). Moreover, they are continuously adjusted and revised in the face of incoming information (Epstein, 2003; Judge et al., 2007). As a result, previous experiences with work characteristics should enhance individual self-efficacy (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Epstein, 2003). However, we also assume that the employees’ perception of the organizations contribution to the common good can increase their self-efficacy. One explanation for this assumption is based on the social identity theory (Ashfort & Mael, 1989; Tajfel & Turner, 1985). It proposes that individuals derive their identity from their membership to relevant social groups. One membership that shapes identity is organizational membership, and if organizations can meet employees’ need for meaning, it leads to positive identification (Ashfort & Mael, 1989). Individuals strive for a positive social identity and identify as employees with the actions and image of their organizations, especially if those organizations are perceived positively by others (Ashfort & Mael, 1989). From a public value perspective, this means that if employees can associate themselves with organizations that fulfill their personal needs and the needs of society, it should lead to a positive anticipated external appraisal and positive feelings, which should enhance their self-concept and accordingly their self-efficacy. More specifically, belonging to an organization that contributes greatly to the common good can facilitate employees’ identification with the organization and perceived meaning in work, thereby positively influencing employees’ self-image as well as their sense of belonging to the organization (Brieger et al., 2020; Jia et al., 2019). Consequently, based on the social identity theory and experience of meaningful work, we argue that the employee’s understanding of contributing to society through membership in an organization with public value orientation should enhance their self-efficacy. Therefore, we assume that organizational membership and perception of public value as a unique additional social context resource will constitute a work characteristic for the employee and expands the framework of the JCM, which is positively related to work engagement and mediated by self-efficacy. Our assumption is supported by numerous studies, which have found individual factors, such as self-efficacy, foster work engagement (Christian et al., 2011; Schaufeli & Salanova, 2007). In addition, studies have found the mediating influence of personal resources like self-efficacy in the relationship between work resources and engagement (Albrecht & Marty, 2020; Llorens et al., 2007; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). These findings confirm Gist and Mitchell’s (1992) theoretical perspective that self-efficacy is an important personal resource which directly and indirectly influences motivation- and performance-related outcomes. Further findings revealed a mediating influence of personal resources on the relationship between work characteristics and engagement, since providing a resourceful environment enhances personal feelings to be capable of controlling the work environment and makes people stay engaged (Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). But there is a lack of research on social context factors that influence self-efficacy (Guan & So, 2016). Additionally, integrating insights from self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2012) and social-cognitive theory (Bandura, 2001), researchers have begun to uncover a supplementary path from self-efficacy beliefs towards work engagement: human agency. Given these theories hold human nature to be inherently proactive and generative (Bakker & van Woerkom, 2017), research has increasingly focused on how need-fulfillment through e.g., the confirmation of self-efficacious beliefs can promote agentic behaviors fostering work engagement, such as an increased focus on the task and increased helpful relating at work (Spreitzer et al., 2005). Based on the literature and previous research findings we expect self-efficacy partially mediate the relationship between work characteristics and work engagement, because we did not include all possible mediators within this process (Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). In light of our study’s work-context, we therefore hypothesize:

Hypothesis 2

Self-efficacy will partially mediate the relationship between work characteristics, including the additional resource as employee perception of public value, and work engagement.

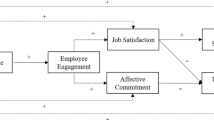

The resulting mediation model is depicted in Fig. 1.

The difference of organizational public value in industries

Linking to the theory of social identity and the sense of belonging to an organization, there can be different perceptions based on the organizational industry. Employees who work in organizations that contribute more to the common good can more easily identify with the organization, which in turn affects their self-efficacy and perceived meaning of work (Brieger et al., 2020). Moreover, research has shown differences regarding the task significance of certain occupations (Grant, 2008; Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006). Employees who worked in jobs that focused on the promotion of human life reported higher task significance owing to the increased salience of their work’s purpose, which resulted in a more affective engagement. Grant (2007) suggested that if employees see that their work positively impacts other people, their productivity increases. Furthermore, employees who know the impact of their work on society or community perceive work as more significant and meaningful (Grant, 2008). Furthermore, the authors Levitats and Vigoda-Gadot (2020) emphasized that employees, especially in the public sector, make not only within, but also outside the organization an engaged contribution to society in order to serve the organization’s mission. However, prior research does not investigated the different perceptions of organizational level contribution to the welfare of others and society in various industries. Referred to the organizational level, we argue that public value is more salient in organizations where the significance of serving a collective is part of its core business. Hence, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3

Employees working in industries with a public focus integrated into their core business will experience higher levels of public value in their work than employees in other industries.

Method

Participants

We tested the hypotheses with data from Switzerland from 2015. Respondents were asked to evaluate the public value of their employing organizations within an online survey. Participants were 949 Swiss German-speaking citizens who were employed at the time of the survey. They were members of a large panel of an independent Swiss market research institute intervista (intervista.ch) and worked across 31 industries. Within the industries, a distinction can be made between public and non-public industries. The public industries include e.g., public administration and healthcare. The non-public industries consists e.g., of banks and insurance. Prior to the main study, a qualitative (N = 5) and quantitative (N = 100) pretest revealed that the length of the survey was adequate and the questions were comprehensible. Respondents’ age ranged between 19 and over 70 years, of whom 46.6% of the respondents were female and 34.2% had a college degree or higher. In addition, 40.0% held a leadership position and 67.1% worked full-time. Overall, this distribution of socio-economic characteristics corresponds to that of the Swiss population, indicating a comparatively representative sample. After completing the socio-demographic data, participants were asked to complete the survey, which included instruments that test our three hypotheses.

Preliminary analysis

Since we used the short version of the public value scale and abbreviated the self-efficacy scale, we tested construct validity by conducting a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using maximum likelihood estimates following Hinkin (1998) and Harman’s one-factor test for endogeneity (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986). These procedures found that common source bias was not an issue, as a common factor would only extract 30.53% of the variance on average, which is far below the recommended threshold. If the first factor had accounted for the majority of variance among all measures, the presence of a substantial amount of common method bias would have been likely (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Following advice by Hinkin (1998), we statistically tested the validity of the variables public value and self-efficacy by conducting an individual confirmatory factor analyses (CFA). To further test a good fit, we performed a test for convergent validity and composite reliability for the variables public value and self-efficacy. We used the following five indices for the results of the CFA: chi-square/df ratio (χ2 / df), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root-Mean-Square-Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and Standardized Root-Mean-Square-Residual (SRMR). All items load significantly (p < .01) on the specified factor. Factor loadings are generally high (≥ 0.71). Maximum likelihood-based estimation results indicate the model fit for public value (χ2 (2) = 146.96; p < .001; CFI = 0.93; TLI = 0.79; RMSEA = 0.27; SRMR = 0.055) and self-efficacy (χ2 (3) = 403.8; p < .001; CFI = 1.0; TLI = 1.0). For the variable public value the SRMR value is below the value of 0.08 and likewise the CFI and TLI show good values for the model fit of the variables public value and self-efficacy, even the RMSEA value does not match the value under 0.05 for the variable public value (Brown, 2015). Moreover, the average variances extracted (AVE) of 0.73 and 0.59 indicate that convergent validity was not an issue for the variables public value and self-efficacy. The composite reliability (CR) for public value is 0.91 and for self-efficacy 0.81. Hence, we are confident in our short measure since the fit indices indicate overall good construct to data fit and suggesting that the short scales are indeed appropriate.

Measures

Work characteristics

For the assessment of the work characteristics, the Job Diagnostic Survey (JDS) of Hackman and Oldham (1975) was used in the German translation (Schmidt & Kleinbeck, 1999). The five core dimensions of the work environment were each assessed with three items: skill variety (α = 0.77) with items like “The job is quite simple and repetitive,” task identity (α = 0.73) with items like “The job provides me the chance to completely finish the pieces of work I begin”, task significance (α = 0.71) with items like “The job is one where a lot of other people can be affected by how well the work gets done”, autonomy (α = 0.75) with items like “The job gives me considerable opportunity for independence and freedom in how I do the work” and feedback from the job (α = 0.75) with items like “After I finish a job, I know whether I performed well”. Participants responded on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely incorrect) to 7 (completely correct).

Public value

Each employee evaluated the public value of their employing organization using the short version of the public value scale (Meynhardt & Jasinenko, 2020) with four items. Respondents indicated the degree to which their employing organization (1) “behaves decently” (moral-ethical dimension), (2) “contributes to the quality of life in society” (hedonistic-aesthetical dimension), (3) “contributes to social cohesion in society” (political-social dimension) and (4) “does good work in its core business” (utilitarian-instrumental dimension). The respondents gave their assessment for each item on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (disagree) to 6 (agree). The measure for public value showed good reliability (α = 0.87).

Self-efficacy

We assessed self-efficacy with three items of the 10-item German General Self-Efficacy Scale (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1999). We selected three items to reduce respondent burden and chose items that had shown the highest discriminatory power across three measurement points: “When I am confronted with a problem, I can usually find several solutions”, “I can solve most problems if I invest the necessary effort” and “I can usually handle whatever comes my way”. These were answered on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s α was 0.66.

Work engagement

We assessed work engagement with the German version of the nine-item Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004) with three items for each of the three aspects of work engagement: vigor, dedication and absorption. Example items included “At my work, I feel bursting with energy” (which represents the aspect of vigor), ”My job inspires me” (which represents the aspect of dedication) and “I feel happy when I am working intensely” (which represents the aspect of absorption). Answers were given on a seven-point Likert scale, anchored at 1 (never) and 7 (always). Cronbach’s α was 0.95.

Control variables

Based on previous studies, we considered several control variables. We controlled for age as a continuous variable; gender (male = 1, female = 2); income (six groups, ranging from a gross monthly income of less than CHF 3,000 to more than CHF 12,000); education (nine groups, ranging from no school-leaving certificate to high tertiary education); current profession (five groups, ranging from apprentice to independent entrepreneur). We also controlled for employee health based on the sick days and the organization’s industry by considering 31 industries.

Analysis and results

Descriptives

Means, standard deviations and correlations between the variables are displayed in Table 1. The results show for work engagement (M = 4.67, SD = 1.12) and public value (M = 4.87, SD = 0.95) positive values. The work characteristics, skill variety (M = 5.48, SD = 1.12), task identity (M = 5.54, SD = 1.18), task significance (M = 5.58, SD = 1.08), autonomy (M = 5.56, SD = 1.10) and feedback from the job (M = 5.59, SD = 1.02), show above-average means. The potential mediator self-efficacy also shows a higher average value (M = 3.12, SD = 0.45). Consistent with other research, we found significant positive correlations between work characteristics and work engagement (see Table 1).

Hierarchical regression

To test H1, that public value acts as an additional resource beyond skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy and feedback from the job in regard to employee work engagement, we conducted hierarchical regression analyses. Table 2 presents the results of the analyses. Model 1 investigated the relationship between the control variables and work engagement, Model 2 analyzed the relationship between skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy, feedback from the job and work engagement. Model 3 examined the relationship between public value and work engagement. The control variables age, gender, education, gross monthly income, industry, current profession and sick days accounted for 9.6% of the total variance in work engagement. The work characteristics entered in Model 2 explained an additional 31.0% of the variance. Public value, entered in Model 3, accounted for an additional 3.7% of unique variance in the overall model. The change in R2 between the second and third model that resulted from the addition of the public value variable was significant (p < .001). The regression weights indicate that public value and skill variety were the most important variables in the overall model. Thus, we could confirm H1.

Mediation analysis

For testing the mediating effect of self-efficacy in the relationship between work characteristics, including the additional resource as public value, and work engagement, we conducted a structural equation modeling (SEM) using IBM SPSS Amos 26. We defined all five work characteristics and public value as the independent variable, self-efficacy as the mediator, and work engagement as the dependent variable. The indirect effect (ab) is described through the path X → M path (a), M → Y path (b). First, we performed a CFA to test the measurement model. The CFA results indicate that each item load significantly (p < .001) on the specific factor. Factor loadings are high (≥ 0.61). The model fit indices also suggest that the measurement model was a good fit to the data (χ2 (406) = 1152.67; p < .001; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.04; SRMR = 0.03). Second, we conducted a structural test for our mediation research model and specified a just-identified structural equation model (df = 0) with good values of CFI = 1.0 and GFI = 1.0. The path coefficients are also significant. Third, we conducted the mediation model test. Table 3 presents the results of the analysis. The results with a 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval indicate a significant mediation model (standardized indirect effects) (see Fig. 2): abskill variety ß = 0.021; 95%-CI = [0.007; 0.039], abtask significance ß = 0.013; 95%-CI = [0.001; 0.029], abfeedback from the job ß = 0.028; 95%-CI = [0.014; 0.046] and abpublic value ß = 0.014; 95%-CI = [0.001; 0.030]. Only the indirect effects of the work characteristics abtask identity ß = -0.001; 95%-CI = [-0.016; 0.013] and abautonomy ß = 0.009; 95%-CI = [-0.006; 0.024] are not significant. The direct effects of all five work characteristics and public value on work engagement also remain significant cskill variety ß = 0.249; 95%-CI = [0.186; 0.314]; ctask identity ß = 0.101; 95%-CI = [0.040; 0.161], ctask significance ß = 0.139; 95%-CI = [0.081; 0.197], cautonomy ß = 0.074; 95%-CI = [0.007; 0.145], cfeedback from the job ß = 0.137; 95%-CI = [0.078; 0.192] and cpublic value ß = 0.198; 95%-CI = [0.138; 0.255]. The results showed the partially mediating effect of self-efficacy on the relationship between work characteristics, including the additional resource as public value, and work engagement. Thus, H2 could be confirmed.

Industry differences in regard to employee public value perception

We created two broad categories to test H3, including only industries for which we had responses from more than 20 respondents. Therefore, out of 31 industries, 18 industries were considered (Table 4). The category of “non-public focus industries” comprised 12 industries. The category of “public focus industries” was composed of six industries.

T-test results revealed significant differences between both categories, with public focus industries (M = 5.16, SD = 0.83, n = 392) show higher public value ratings than non-public focus industries (M = 4.67, SD = 0.98, n = 420), t(811) = 7.56, p < .001. The effect size indicated a Cohen’s d = 0.53, revealing a medium to large effect. Therefore, H3 could be confirmed.

Robustness analysis

For the robustness of our results of H3, we analyzed the public value score of public and non-public industries from a second dataset in Switzerland. The data were collected via an online-survey in 2019. Participants were 7430 Swiss German-speaking citizens which were employed at the time of the survey. They were members of a large-scale representative online-survey of an independent Swiss market research institute intervista (intervista.ch) and worked across 27 industries. Within the industries, also a distinction between public and non-public industries can be made. Participants age ranged between 18 and over 70 years. Moreover, 47,3% of the respondents were female, 38,7% had a college degree or higher. In addition, 38,8% held a leadership position and 58,8% worked full-time. Overall, the distribution of socio-economic characteristics of the sample corresponds to that of the Swiss population, which is an indication of a comparatively representative sample. After collecting the demographic data, the participants were asked to complete the survey.

To support the results of H3, we calculated an independent samples t-test, which also revealed significant differences between the two categories. Industries with public interest (M = 5.21, SD = 0.84, n = 2833) show higher public value ratings than industries without public interest (M = 4.78, SD = 1.00, n = 4597), t(7428) = 18.88, p < .001. The data indicated a medium effect with Cohen’s d = 0.61. Thus, the additional test also analyzes whether the public value of organizations with a public focus receives higher ratings than those with a less public focus. Consequently, the additional consideration of the data from 2019 underpins the results of H3.

Discussion

Finding meaning and purpose in work is highly relevant for employees (Hackman & Oldham, 1975; Jasinenko & Steuber, 2023; Wrzesniewski et al., 2003), especially in time of grand challenges increasing pressure on organizations. While previous studies have focused on the positive effects of work characteristics in terms of employees’ work behavior and meaningful work (e.g., Milovanska-Farrington, 2023, Rai & Maheshwari, 2020; Saks, 2006), the social context factors as additional work characteristics have remained largely unexplored. Hence, we theoretically argued and empirically tested, whether the perceived public value contribution of an organization is an additional unique work characteristic and resource for the employee in the JCM, which is positively related to employee work engagement. This study contributes to the theoretical foundation of JCM by supporting previous findings on the positive relationship between work characteristics and positive work outcomes, such as work engagement. But by integrating the public value theory (Meynhardt, 2009, 2015) into the JCM, we broaden the perspective of existing work design models by going beyond the previous work characteristics and taking the social context into account and using the conceptualization of organizational value creation for the common good. Accordingly, we also support previous studies on public value and positive organizational and individual outcomes (Grubert et al., 2022; Ritz et al., 2023). However, it is the first study to our knowledge, to propose an extension of JCM with social contextual factors underlying intra-individual processes and to investigate in this context the relationship between organizational public value and positive work outcomes. Thus, we tried to contribute to bridge the gap to understand the value creation processes at the micro- and macro-level by investigating the potential benefits of public value, which positively affects changes at the organizational and individual level. Our study contributes novel empirical evidence to the role public value plays for employees’ work engagement using a Swiss citizen sample and real organizations from public and non-public industries.

As hypothesized, our research reveals three key findings: First, to extend the JCM by adding social contextual factors is important. The results are consistent with our first hypothesis about the positive relationship of work characteristics, including the employees’ perceptions of their organization’s public value, and work engagement. Specifically, hierarchical regression analysis demonstrated the positive relationship between public value and work engagement beyond the work characteristics skill variety, task identity, task significance, autonomy and feedback from the job. We found this result despite our conservative approach to testing H1, because we entered all other work characteristics in the first step of the regression so that all shared variance between the motivational work characteristics and public value was associated with the other five work characteristics. Furthermore, the regression coefficients revealed that public value was the second most important variable beside skill variety that was linked to work engagement. Second, to explain the phenomena behind the relationship, individual factors are important. The results also support our second hypothesis that self-efficacy partially mediates the relationship between work characteristics, including the additional resource as public value, and work engagement. The results also showed that public value is one of the three strongest effect sizes on work engagement via self-efficacy and also in the direct effect on work engagement. Third, the perception of public value differs from sectoral factors. The reported findings also correspond to our third hypothesis that employees who worked in industries with a strong public focus had a higher perception of the public value of their organizations than employees who worked in industries without such a focus. To strengthen these result, we considered another dataset from 2019, which confirmed this as well.

Based on these findings and building on extant research, our results provide evidence that it is necessary that work design theory looks at different sources of work meaningfulness (Glavas, 2012). Apart from other work characteristics that focus more on the task level, the social context factor public value is important for employee engagement and should be seen as an additional work characteristic within the JCM. Although we applied a conservative testing of our hypotheses, we found evidence for a significant and unique contribution of public value. Thus, for a more comprehensive view on work design models and the impact of work design on employee well-being, researchers should take into account the value creation of an organization within a community or society. We assumed that if employees are capable to see a significant societal value contribution of their employing organization, their self-efficacy beliefs are activated by their membership in the organization. As a result, they feel more capable of contributing to something larger in their environment. These positive feelings are likely to promote the experience of confidence and meaningfulness so that employees engage more strongly with their work (Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). Accordingly, highlighting the positive relationship between public value-oriented organizational behavior and a flourishing a healthy workplace, our findings provide new insights for research on positive organizational scholarship and an extension of the JCM. In addition, our analysis showed regardless of sectoral affiliation in our first hypothesis, there was a positive association with employees’ work engagement. This is based on the assumption that all organizations have a social function and are relevant to society (Meynhardt, 2015). Despite the lower perception of public value in non-public organizations, they can also benefit from the advantages of public value. However, our third hypothesis revealed differences in the perception of public value with regard to sectoral affiliation. As already assumed, one possible explanation for the difference in public value perception between public and non-public industries could come from social identity theory, which assumes that individuals strive for a positive social identity and self-image (Ashforth & Mael, 1989) which in turn affects their meaning of work (Brieger et al., 2020). Therefore, employees find identification with the job role that has high task significance. In this context, Grant (2008) showed that task significance is associated with a greater awareness of its social influence and value. Thus, we assumed that the perception of public value of a public organization is higher among its employees, because their profession has a direct influence on them and the social identity of their work role is more in focus. For employees in non-public organizations, where the social contribution of the organization to the common good is not directly tangible in the work environment and in the work characteristics, there is a lower perception of public value. A further possible explanation could be that employees in public organizations show an increased public service motivation, which concerns the motivation of individuals to contribute to society as a whole by providing public services and serving the public interest (Ritz et al., 2020; Weißmüller et al. 2022). This leads to a greater tendency to seek employment in the public sector (Asseburg & Homberg, 2020; Ritz et al., 2023; Vandenabeele, 2008). Existing studies showed that public service motivation is an important facet of value congruence between public employees and public employers (Bright, 2008; Teo et al., 2016). Thus, by measuring the common good contribution of an organization as the fulfillment of four basic needs, following Meynhardt’s (2009, 2015) conceptualization of public value, the needs of employees can be satisfied and increase the perception of the public value of the organization.

Theoretical implications

There are at least four reasons why the results of our study are considered theoretically important. First, our study highlights the positive relationship between work characteristics, including the additional resource public value, and work engagement. Previous studies have examined the relationship between work characteristics and positive work outcomes like work engagement or motivation. However, the social context factors in this interaction has not been sufficiently investigated. Some studies consider social support, feedback from others or interdependence as social work characteristics as well as ergonomics, physical demands or work conditions as contextual work characteristics (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006), but they do not consider the social perspective and the embedding of organizations into society. Therefore, our study complements the JCM with the valuable unique social context work characteristic of public value, which acts as a resource for employees, and is a further antecedence for the occurrence of work engagement. Second, the present study examined a mediation model to understand the relationship between the work characteristics, including public value, and work engagement via self-efficacy. Although past research has investigated that self-efficacy plays a key role in determining meaningfulness of work and employees’ well-being (Christian et al., 2011; Schaufeli & Salanova, 2007), empirical investigations of this important variable have been incomplete. Our results confirmed the mediation model and made an important contribution to science by including individual factors in explaining the processes on the micro- and macro-level in the context of work design models. Third, we were able to make an additional contribution to science by shed light on the perception of public value in public and non-public organizations. However, most of the existing related literature focuses on public organizations for e.g., public administration, but there is a need to shift the attention also to non-public organizations in this context. As studies have already shown all sectors can contribute to the common good (Grubert et al., 2022). Even if our study showed that the contribution to the common good of public organizations is perceived higher than of non-public organizations, it does not rule out that all organizations are relevant for society (Drucker, 2011) as they all confront with the current grand challenges. Finally, our study made an important contribution to the public value research stream by attempting to bridge the gap between macro-level (organizational public value, work characteristics) and micro-level (employees work experience) processes. This complements previous public value studies like those from Brieger et al. (2020), Grubert et al. (2022) and Ritz et al. (2023).

Managerial implications

Our findings offer important insights for management practice and, in particular, for practical implications in the areas of human resources and leadership. They provide evidence of the importance of an organization’s public value in addition to the other work characteristics for an engaged and healthy workforce. Organizations can enrich employees’ membership in the organization and thereby foster meaningfulness at work, for example by promoting values and goals of the organization (Pratt & Ashfort, 2003). Therefore, management strategies and measures should be aimed at increasing employees’ experience of meaningfulness at all these levels. Public value should be seen as one source of enhanced meaningfulness at work at the organizational level. Making the purpose of tasks transparent and the organization as a whole and pointing to the connection of the core business with its contribution to society is essential for employees to experience meaningfulness at the organizational level. As our results demonstrate, the experience of doing something good for society by being a member of an organization with a high public value is likely to increase employee engagement. It has been shown that especially this combination of high work engagement and workplace well-being is highly relevant for key organizational outcomes (Leitão et al., 2019). Results revealed, for example, that engaged employees were not only more likely to report higher well-being levels and better performance at the task and organizational level, they also reported a better adaptability in situations of change. In times of crisis and grand challenges, this change became particularly visible as employees were confronted with high work demands. Companies and managers in particular are responsible for ensuring that employee engagement does not suffer as a result. Moreover, respecting society’s needs and expectations in business models, services and products should therefore be integral to management decisions. In this process, a dialogue with society and an intensive reflection among organizational members on whether business activities are aligned with societal needs is necessary to create public value. But also a transparent and regular communication with the organization’s employees in order to identify their needs and perceived public value of the organization in which they work is an important measurement. In addition, communicating the public value contribution outside the organization and integrating it into internal and external projects can also be useful. Our results indicate that taking such steps in stressing values and goals beyond financial aspects and providing employees with opportunities to see the greater purpose of their work should lead to increased work engagement.

Limitations and avenues for future research

There are limitations to the present research despite our results. One important limitation is that our study is based on cross-sectional data, so that no causal interpretation of the results can be made. Moreover, the data were self-reported and collected at the same time in a cross-sectional research design, common method and common source bias might be present (Podsakoff et al., 2003). For this reason, we used several methods and appropriate survey designs in advance to minimize the potential of common method bias, tested subsequently whether it had been a threat and followed established recommendations (Jakobsen & Jensen, 2015; Podsakoff et al., 2003). First, to avoid common method bias at the comprehensive stage and to reduce social desirability bias, we assured anonymity of all responses to our study participants. Second, we made sure that all items were formulated precisely by conducting a qualitative and quantitative pretest. Third, our online questionnaire included different response formats and scale endpoints for our items, which should decrease method biases caused by anchoring effects (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Also the survey used questionnaires that had been tested in previous studies. Fourth, the items were part of a large-scale questionnaire, so participants had limited knowledge of the purpose of the study and thus would not have guided their responses appropriately for consistency. Fifth, our study included several objective control variables, such as age, gender, income, education, current profession, the industry of the organization as well as employee health days, which allowed us to control for differences in response bias between groups. Sixth, we used Harman’s single-factor test (Harman, 1976) to assess retrospectively the presence of common method bias. Nonetheless, that common method bias could threaten the validity of our results because the predictor and criterion variables were from the same source (Podsakoff et al., 2003). However, considering all methods, we concluded that bias from common methods did not pose a significant threat to our data for the analysis. We created sufficient variance with the different organizations from the public and non-public industries and used a sample of a relatively large number of 949 individual respondents drawn from the general population of Swiss citizens. Also, the latent factor tests for construct validity did not reveal any such issues. Moreover, methodological research by Siemsen et al. (2010) indicated that regression estimates of interaction effects would be attenuated rather than artificially increased by common method bias, further supporting the robustness of our results. Additional limitations are that other factors might have influenced the perception of public value, for example, employees’ attitudes toward supervisors. Since the company name of the employing organization was kept anonymous and our analysis relied solely on self-reported data, we are not able to compare public value ratings across team or organizational levels or to compare the evaluations of the employees with other sources, such as assessments of the respective supervisor or coworkers. Finally, we provided a solid theoretical rationale for our assumption that an organization’s public value is positively related to employee work engagement in addition to the work characteristics of the JCM, other pathways are still possible. For example, more engaged workers could be more likely to evaluate the public value of their employing organization more highly than less engaged employees.

However, our study points out further avenues for future research. The study design did not allow for detecting causality between the relationship of public value and employee well-being. Thus, we hope researchers will address this issue and examine this relationship for example in long-term studies and with an experimental design. Further, individual differences could shape the perception of public value and its relevance might be higher for certain individuals. Research has shown for example that individuals with higher prosocial values were more concerned about the impact of their work on other people, and the experience of task significance strongly affected their performance (Grant, 2008). Additionally, not only individual values could interfere with the perception of public value, but the orientation toward work could also be important. Work orientations can be relevant to a better understanding how employees derive meaning from their work (Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). Individuals who see their job as a calling, as socially valuable and purposeful, could be more strongly affected by public value. Researchers should address the influence of individual differences in values and work orientations concerning the perception of public value and its relationship with well-being.

Conclusion

We have analyzed the relevance of an organization’s public value for employee outcomes across various industries and demonstrated a positive relationship between work characteristics, including public value, and employee work engagement. Additionally, our findings have shown that the positive relationship was partially mediated by self-efficacy. This study is an example how to reintegrate society into work design research and can be seen as a renaissance of considering societal factors in employees’ workplace experience. Organizations should acknowledge public value as a source of meaning and additional resource for employees to create a more engaged and healthy workforce, especially in times of grand challenges organizations are confronted with. More specifically, organizational public value contributes positively to the employee’s identification with the organization and promotes the meaning of work, which leads to a stronger sense of self-efficacy and work engagement. In other words, organizational public value serves as a resource for the individual at work. The evidence from our study should encourage researchers to take another perspective on work design and reintegrate the societal dimension of organizational activities. The extension of the job characteristics model towards social context may allow to better understand the social nature of work with all its cultural, political and moral dimensions.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2019). On corporate social responsibility, sensemaking, and the search for meaningfulness through work. Journal of Management, 45(3), 1057–1086. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317691575.

Albrecht, S. L., & Marty, A. (2020). Personality, self-efficacy and job resources and their associations with employee engagement, affective commitment and turnover intentions. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31, 657–681. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1362660.

Albrecht, S. L., Green, C. R., & Marty, A. (2021). Meaningful work, job resources, and employee engagement. Sustainability, 13(7), 4045. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074045.

Allan, B. A., Batz-Barbarich, C., Sterling, H. M., & Tay, L. (2019). Outcomes of meaningful work: A meta-analysis. Journal of Management Studies, 56(3), 500–528. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12406.

Ashfort, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39. https://doi.org/10.2307/258189.

Asseburg, J., & Homberg, F. (2020). Public service motivation or sector rewards? Two studies on the determinants of sector attraction. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 40(1), 82–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X18778334.

Bailey, C., Madden, A., Alfes, K., & Fletcher, L. (2017). The meaning, antecedents and outcomes of employee engagement: A narrative synthesis. International Journal of Management Reviews, 19, 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12077.

Bakker, A. B., & Van Woerkom, M. (2017). Flow at work: A self-determination perspective. Occupational Health Science, 1, 47–65.

Bandura, A. (1983). Self-efficacy determinants of anticipated fears and calamities. Journal of personality and social psychology, 45(2), 464–469. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.2.464

Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachandran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (pp. 71–81). Academic.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control. Freeman

Bandura, A. (2001). Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26.

Barrick, M. R., Mount, M. K., & Li, N. (2013). The theory of purposeful work behavior: The role of personality, higher-order goals, and job characteristics. Academy of Management Review, 38(1), 132–153. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.10.0479.

Brammer, S., Branicki, L., Linnenluecke, M., & Smith, T. (2019). Grand challenges in management research: Attributes, achievements, and advancement. Australian Journal of Management, 44(4), 517–533. https://doi.org/10.1177/0312896219871337.

Brieger, S. A., Anderer, S., Fröhlich, A., Bäro, A., & Meynhardt, T. (2020). Too much of a good thing? On the relationship between CSR and employee work addiction. Journal of Business Ethics, 166(2), 311–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04141-8.

Bright, L. (2008). Does public service motivation really make a difference on the job satisfaction and turnover intentions of public employees? The American Review of Public Administration, 38(2), 149–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074008317248.

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Methodology in the social sciences (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Bryson, J. M., Barberg, B., Crosby, B. C., & Patton, M. Q. (2021). Leading Social Transformations: Creating Public Value and Advancing the Common Good. Journal of Change Management, 21(2), 180–202.

Cartwright, S., & Holmes, N. (2006). The meaning of work: The challenge of regaining employee engagement and reducing cynicism. Human Resource Management Review, 16, 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2006.03.012.

Chaudhary, R. (2022). Deconstructing work meaningfulness: Sources and mechanisms. Current Psychology, 41(9), 6093–6106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01103-6

Chen, Z. J., Zhang, X., & Vogel, D. (2011). Exploring the underlying processes between conflict and knowledge sharing: A work–engagement perspective. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(5), 1005–1033. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00745.x.

Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., & Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work Engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with Task and Contextual Performance. Personnel Psychology, 64, 89–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x.

Crawford, E. R., Lepine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout: A theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 834–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019364.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Self-determination theory. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 416–436). Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249215.n21

Demirtas, O., Hannah, S. T., Gok, K., Arslan, A., & Capar, N. (2017). The moderated influence of ethical leadership, via meaningful work, on followers’ engagement, organizational identification, and envy. Journal of Business Ethics, 145, 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2907-7.

Dinh, L. (2020). Determinants of employee engagement mediated by work-life balance and work stress. Management Science Letters, 10(4), 923–928. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2019.10.003.

Drucker, P. F. (2011). Management: An abridged and revised version of management: Tasks, responsibilities, practices. Routledge.

Dutton, J., & Glynn, M. A. (2008). Positive Organizational Scholarship. In C. L. Cooper & J. Barling (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational behavior. Vol. 1: Micro approaches (pp. 693–712). SAGE.

Epstein, S. (2003). Cognitive-experiential self-theory of personality. In I. B. Weiner, D. K. Freedheim, J. A. Schinka, & W. F. Velicer (Eds.), Handbook of psychology (pp. 159–184). Wiley.

Fairlie, P. (2011). Meaningful work, Employee Engagement, and other Key Employee outcomes: Implications for human Resource Development. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 13(4), 508–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422311431679.

Frieder, R. E., Wang, G., & Oh, I. S. (2018). Linking job-relevant personality traits, transformational leadership, and job performance via perceived meaningfulness at work: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(3), 324–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000274.

Gabriel, K. P., & Aguinis, H. (2022). How to prevent and combat employee burnout and create healthier workplaces during crises and beyond. Business Horizons, 65(2), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2021.02.037.

Gartenberg, C., Prat, A., & Serafeim, G. (2019). Corporate purpose and financial performance. Organization Science, 30(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2018.1230.

Gist, M. E., & Mitchell, T. R. (1992). Self-efficacy: A theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Academy of Management review, 17(2), 183–211. https://doi.org/10.2307/258770

Glavas, A. (2012). Employee engagement and sustainability: A model for implementing meaningfulness at and in work. The Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 46, 13–29. https://doi.org/10.9774/GLEAF.4700.2012.su.00003.

Grant, A. M. (2007). Relational Job Design and the motivation to make a Prosocial difference. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 393–417. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2007.24351328.

Grant, A. M. (2008). The significance of task significance: Job performance effects, relational mechanisms, and boundary conditions. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 108–124. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.108.

Grubert, T., Steuber, J., & Meynhardt, T. (2022). Engagement at a higher level: The effects of public value on employee engagement, the organization, and society. Current Psychology, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03076-0.

Guan, M., & So, J. (2016). Influence of social identity on self-efficacy beliefs through perceived social support: A social identity theory perspective. Communication Studies, 67(5), 588–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2016.1239645.

Hackman, R. J., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the Job Diagnostic Survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076546.

Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B., & Ahola, K. (2008). The job demands-resources model: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work and Stress, 22(3), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370802379432.

Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis (3rd ed.). The University of Chicago.

Hartley, J., Alford, J., Knies, E., & Douglas, S. (2017). Towards an empirical Research Agenda for Public Value Theory. Public Management Review, 19(5), 670–685. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2016.1192166.

Hinkin, T. R. (1998). A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organizational Research Methods, 1(1), 104–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442819800100106.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513.

Humphrey, S. E., Nahrgang, J. D., & Morgeson, F. P. (2007). Integrating motivational, social, and contextual work design features: A meta-analytic summary and theoretical extension of the work design literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1332–1356. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1332.

Jakobsen, M., & Jensen, R. (2015). Common method bias in public management studies. International Public Management Journal, 18(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2014.997906.

Jasinenko, A., & Steuber, J. (2023). Perceived organizational purpose: Systematic literature review, construct definition, measurement and potential employee outcomes. Journal of Management Studies, 60(6), 1415–1447. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12852.

Jia, Y., Yan, J., Liu, T., & Huang, J. (2019). How does Internal and External CSR affect employees’ work Engagement? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(14), 2476. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142476.

Judge, T. A., Jackson, C. L., Shaw, J. C., Scott, B. A., & Rich, B. L. (2007). Self-efficacy and work-related performance: The integral role of individual differences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 107–127. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.107.

Jurek, P., & Besta, T. (2021). Employees’ self-expansion as a mediator between perceived work conditions and work engagement and productive behaviors. Current Psychology, 40, 3048–3057. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00241-w.

Leitão, J., Pereira, D., & Gonçalves, Â. (2019). Quality of work life and organizational performance: Workers’ feelings of contributing, or not, to the organization’s productivity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(20), 3803. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16203803.

Levitats, Z., & Vigoda-Gadot, E. (2020). Emotionally engaged civil servants: Toward a multilevel theory and multisource analysis in public administration. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 40(3), 426–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X18820.

Liu, D., Chen, Y., & Li, N. (2021). Tackling the negative impact of COVID-19 on work engagement and taking charge: A multi-study investigation of frontline health workers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(2), 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000866.

Llorens, S., Schaufeli, W., Bakker, A., & Salanova, M. (2007). Does a positive gain spiral of resources, efficacy beliefs and engagement exist?. Computers in human behavior, 23(1), 825–841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2004.11.012

Lysova, E. I., Allan, B. A., Dik, B. J., Duffy, R. D., & Steger, M. F. (2019). Fostering meaningful work in organizations: A multi-level review and integration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110, 374–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JVB.2018.07.004.

May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(1), 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317904322915892.

Meynhardt, T. (2009). Public value inside: What is public value creation? International Journal of Public Administration, 32(3–4), 192–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900690902732632.

Meynhardt, T. (2015). Public value: Turning a conceptual framework into a scorecard. In J. M. Bryson, B. C. Crosby, & L. Bloomberg (Eds.), Public Value and Public Administration (pp. 147–169). Georgetown University Press.

Meynhardt, T., & Jasinenko, A. (2020). Measuring public value: Scale development and construct validation. International Public Management Journal, 24(2), 222–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2020.1829763.

Milovanska-Farrington, S. (2023). Gender differences in the association between job characteristics, and work satisfaction and retention. American Journal of Business, 38(2), 62–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJB-07-2022-0115.

Morgeson, F. P., & Humphrey, S. E. (2006). The Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ): Developing and validating a comprehensive measure for assessing job design and the nature of work. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(6), 1321–1339. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.6.1321.

Morgeson, F. P., & Humphrey, S. E. (2008). Job and Team Design: Toward a More Integrative Conceptualization of Work Design. In J. J. Martocchio (Eds.), Research in personnel and human resources management. (vol. 27, pp. 39–91). Emerald.

Newman, A., Eva, N., Bindl, U. K., & Stoverink, A. C. (2022). Organizational and vocational behavior in times of crisis: A review of empirical work undertaken during the COVID-19 pandemic and introduction to the special issue. Applied Psychology, 71(3), 743–764. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12409.

Panda, A., Sinha, S., & Jain, N. K. (2022). Job meaningfulness, employee engagement, supervisory support and job performance: A moderated-mediation analysis. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 71(6), 2316–2336. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-08-2020-0434.

Parker, S. K., Wall, T. D., & Cordery, J. L. (2001). Future work design research and practice: Towards an elaborated model of work design. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 74, 413–440. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317901167460.

Pearson, C. M., & Mitroff, I. I. (2019). From crisis prone to crisis prepared: A framework for crisis management. In Risk management (pp. 185–196). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.5465/AME.1993.9409142058.