Abstract

Adverse life events have been shown to increase the chances of harmful thoughts, or behavior against oneself. This study aims to fill this gap by identifying how adverse life events (witnessing a friend’s or family member’s self-injury, eating behavior problems, concern about sexual orientation, physical or sexual abuse) experienced by adolescents and young adults are associated with different indicators of suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury behaviors, according to gender and age. Participants were 625 young people aged between 12 and 25 years (Mean = 15.91, SD = 2.44), of whom 61.7% were girls. Of total participants, 53.44% reported adverse life events. Physical or sexual abuse was more associated with suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury compared to being witness to a friend’s self-injury. Girls who experienced physical abuse had more suicidal ideation than boys, while boys who experienced sexual abuse had more suicidal ideation than girls. Young adults who had experienced sexual abuse and those who witnessed a friend’s self-injury reported more non-suicidal self-injury attempts than adolescents in the same situations. For eating problems, adolescents showed more non-suicidal self-injury attempts than young adults. The findings underline the importance of considering adverse life events in order to prevent suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Suicidality includes different manifestations of suicidal behavior, ranging from suicidal ideation to suicidal planning and suicide attempts (Branley-Bell et al., 2019; Fonseca-Pedrero & Pérez de Albéniz, 2020). On the other hand, non-suicidal self-injury is defined as repetitive, intentional, and socially unacceptable harm to the body without suicidal intent or fatal outcome, usually for the purpose of dismissing emotional distress (Nock, 2010). Both behaviors have increased considerably in adolescents and young adults. The prevalence of suicidal ideation is between 9.9% and 18%, suicidal planning between 5.6% and 9.9%, and suicidal attempts between 0.9% and 6%, depending on the country in which the study was conducted (Blasco et al., 2019; Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2021). The lifetime prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury is around 17% in adolescents (10–17 years) and 13.4% in young adults (18–24 years) (Swannell et al., 2014). Previous research suggests that non-suicidal self-injury may increase risk for suicide attempts (Andover et al., 2012). Suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury behaviors often co-occur in around 7.7% of youth showing a greater association in females than in males (Voss et al., 2020). The early identification of self-injury and suicide risk factors is vital to prevent suicide completion.

Most studies indicate a higher prevalence of suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury behaviors in girls than boys (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2022; Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2022). Also, adolescent girls with suicide attempts have a greater risk of disease and mortality (Soullane et al., 2022). In terms of age, older adolescents report the highest risk of suicidal behaviors (Carli et al., 2014), while younger adolescents experience non-suicidal self-injury more often (Cipriano et al., 2017; Wilkinson et al., 2022). The prevalence of suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury risk has also been found to be increased in adolescents vulnerable to mental health problems. For example, young people with bipolar experience show a prevalence of 46.9% in suicidal ideation, 26.6% in suicide planning, and 6% in suicide attempts (Fumero et al., 2021). Emotional and behavior problems, problems with peers, and difficulties associated with hyperactivity explained suicide risk. In adolescents and young people with borderline personality traits, the prevalence is higher: 79.6%, 67.9%, 26.2%, and 44.7% for suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, suicidal attempts, and non-suicidal self-injury, respectively (Marrero et al., 2023). Personal and social factors that have been associated with suicidal risk and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents and young people with borderline personality traits include difficulties in impulse control for suicide attempts and low family satisfaction for self-injury. Previous studies by the research team show that several personal, social, family, and contextual factors differentially impact the different indicators of suicidal and self-injurious risk.

Adolescence is a period of physical and psychological changes that can place young people in challenging situations. The most frequent concerns at this stage include the search for identity, sexual behavior, feeling comfortable with their body, the consumption of psychoactive substances, social-emotional problems, communication in the family, and integrating into a group. Some adolescents have difficulty coping with the several challenges their developmental period and may experience these life situations as adversity. In our considered perspective, adverse life events may underlie suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury risk and even vulnerability to diverse mental health problems. In this study, we distinguish between adverse life events and adverse childhood experiences, since adverse life events included in this research (concern about sexual orientation, eating behavior problems, or sexual/physical abuse) could be co-occurring with the participants’ developmental period (adolescence). The term adverse childhood experiences, however, is used to refer to childhood experiences related to psychological, physical, and sexual abuse, or household dysfunction, such as domestic violence, substance use, and incarceration (Felitti et al., 1998), which may have already remitted. They are usually studied in adults over 18 years of age.

Despite data on the epidemiology of suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury behaviors as a function of age and gender, few studies have analyzed age and gender differences in suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury behaviors, according to experience of adverse life events. In this sense, we explore this important knowledge by investigating the prevalence of suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury risk in adolescents and young people who have experienced adverse life situations compared with those who have not. Moreover, given that some situations may be more frequent in boys than in girls, it is also important to study whether there are differences in suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury, according to the type of adverse life event and gender. Although previous research has mainly focused on analyzing suicidal or self-injurious risk in a broad sense, this study examines whether experience of these adverse situations can have a differential impact on suicidal ideation, planning, or attempts at a specific level, as well as in non-suicidal self-injury ideation and attempts.

Adverse life events and adverse childhood experiences have been shown to be related to suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury behaviors (Ehlers et al., 2022; Horváth et al., 2020; Sahle et al., 2022; Rajhvajn Bulat et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023). Specifically, physical attack, witnessing a traumatic event, serious accident and, above all, rape/sexual abuse increase the risk of suicidal attempts (Miché et al., 2020). Similarly, childhood maltreatment—mainly sexual and physical abuse—is associated with non-suicidal self-injury in both adolescents and adults (Liu et al., 2018). In addition, adolescents with a minority sexual orientation or with symptoms of eating disorders show a greater risk of suicidal or self-injury behavior (Perkins et al., 2021; Peters et al., 2020).

Although past research has made it possible to expand knowledge about how adverse life events are associated with suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury behaviors, the relationship between some adverse life events, suicide, and non-suicidal self-injury is still inconclusive. This study aims to fill this gap by analyzing how the different common adverse life events (concern about sexual orientation, eating behavior problems, or sexual/physical abuse) could relate to varying types of indicators of suicide (ideation, planning, and attempts) and non-suicidal self-injury (ideation and attempts), considering both gender and age. The study objectives are as follows: (1) To identify the prevalence of different indicators of suicide and non-suicidal self-injury and co-occurrence at early ages from 12 to 25 years; (2) To assess the prevalence of suicide and non-suicidal self-injury in groups with and without experience of adverse life events; and (3) To assess the risk of suicide and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents and young adults who have experienced different adverse life events, such as sexual abuse, witnessing self-injury of friends, concern about sexual orientation, eating behavior problems, and physical abuse, according to gender and age.

Method

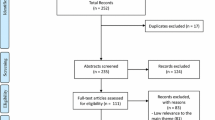

Participants and procedure

The participants were 625 Spanish young people aged between 12 and 25 years (Mean = 15.91, SD = 2.44), of whom 85.6% were between 12 and 18 years old; 61.7% were girls; and 14.4% were between 19 and 25 years old, with 72.2% of girls. Of the total number of participants, 53.44% reported having experienced an adverse life situation.

Several state secondary schools were contacted to participate in the research. They were informed that the aim was to identify the personal, family, and social factors involved in suicidal and self-injurious behaviors. Secondary school students were asked for informed consent from themselves and their parents, or legal guardians. The instruments were administered online in the classroom under the supervision of teaching staff with an approximate duration of one hour. Participants over 18 years of age were undergraduate psychology students who received an extra grade for participating. The instruments were completed online at home. At all times, anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed, and participants were informed that they could leave the study at any time. The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical approval for the conduct of the research study was granted by the Animal Welfare and Research Ethics Committee of the University of La Laguna, Spain (CEIBA2020-0412).

Instruments

The Paykel Suicide Scale (PSS, Paykel et al., 1974) is a self-report measure that uses five items to assess suicidal ideation (two items), suicidal planning (two items), and suicidal attempt (one item). The response format is dichotomous (Yes or No). This questionnaire enables a global score of suicidal risk to be obtained by adding the affirmative answers to the five items. Higher scores are related to greater suicidal risk. The instrument has been shown to meet adequate psychometrical criteria in young Spaniards (Fonseca et al., 2018) with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86.

Non-suicidal self-injury was evaluated using two questions that were answered as Yes or No, adapted from O’Connor et al.’s (2009) self-report survey: (1) Have you ever seriously thought about overdosing or trying to harm yourself, but actually did not? (Non-suicidal self-injure ideation); (2) Have you ever deliberately taken an overdose (for example, pills or other medication) or tried to harm yourself in some other way (such as cutting yourself), with no intention of dying? (Non-suicidal self-injury attempts). Participants who answered the non-suicidal self-injury attempts affirmatively indicated the type of act they had carried out on the list according to the most frequent type of non-suicidal self-injury reported in the literature (cutting themselves, hitting body parts, scratching themselves, drug overdoses, biting themselves, pinching themselves, burning their skin, or other acts). In addition, one last open question inquired about the reasons that had prompted participants to act in that way.

Adverse life events were assessed through a question devised by the authors: Have you been through any of these situations at some point in your life? The situations listed were as follows: witness to a friend’s self-injury (hitting or cutting themselves, etc.), witness to a family member’s self-injury (hitting or cutting themselves, etc.), eating behavior problems, concern about sexual orientation, physical abuse (others have hit you for no reason), sexual abuse (sex without your consent), or others (write down situations not included in the list). The participants were asked to mark the one they considered most serious. In this way, the number of young people who answered affirmatively to at least one of the situations was recorded.

Participants also provided socio-demographic information in which gender, age, academic year, and study center were recorded.

Data analysis

The statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25. First, the prevalence and co-occurrence of indicators of suicide and non-suicidal self-injury in the total sample were calculated, along with the type and reasons for non-suicidal self-injury attempts, through frequencies analysis and Pearson correlation. Second, chi-squared tests were applied to analyze the prevalence of suicide and non-suicidal self-injury for groups with and without experience of adverse life events and for each type of adverse life event. Third, we used two-way MANOVAs to explore the effects of adverse life events, according to type and gender, on the different forms of suicide (suicidal ideation, suicidal planning, and suicidal attempts) and non-suicidal self-injury (non-suicidal self-injury ideation and non-suicidal self-injury attempts). In the same way, we used two-way MANOVAs to explore the effect of type of adverse life event and age on suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury. The participants were divided into two age groups (adolescents of 12–18 years and young adults of 19–25 years). Univariate contrasts were analyzed with t-tests.

Results

Prevalence of suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury and co-occurrence

Of the total sample, 47.6% reported suicidal ideation, 37.4% suicidal planning, and 13% suicidal attempts. Regarding non-suicidal self-injury, 29.6% reported non-suicidal self-injury ideation and 19% non-suicidal self-injury attempts. Additionally, co-occurrence of suicidal ideation and non-suicidal self-injury ideation appeared in 24.96% (N = 156). There was also co-occurrence between suicidal planning and non-suicidal self-injury ideation in 23.84% (N = 149), and between suicidal attempts and non-suicidal self-injury ideation (10.24%, N = 64). Similarly, analysis of co-occurrence between suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury attempts revealed that 15.52% (N = 97) reported non-suicidal self-injury attempts and suicidal ideation; 15.36% (N = 96) reported non-suicidal self-injury attempts and suicidal planning; and 9.76% (N = 61) reported non-suicidal self-injury attempts and suicidal attempts. Of the participants who reported witnessing a friend’s self-injury, 33.93% had non-suicidal self-injury ideation and 20.54% had non-suicidal self-injury attempts. Correlational analyses showed significant relationships between the different indicators of suicidal risk and non-suicidal self-injury. Specifically, suicidal ideation showed a correlation of 0.55 (p < .001) and 0.42 (p < .001) with non-suicidal self-injury ideation and non-suicidal self-injury attempts, respectively. Suicidal planning showed a correlation of 0.63 (p < .001) and. 52 (p < .001), while suicide attempts showed correlations of 0.42 (p < .001) and 0.55 (p < .001) with non-suicidal self-injury ideation and non-suicidal self-injury attempts, respectively.

The most frequent self-injuries were cutting themselves (47.2%), banging their heads, or other body parts (14.2%), scratching themselves (12.6%), drug overdoses (10.2%), biting themselves (5.5%), pinching themselves (4.7%), and burning themselves (2.4%). The reasons for non-suicidal self-injury mentioned by the participants were mainly personal problems (31.6%), family problems (17.1%), depression, or feeling lonely (19.7%), punishing themselves for negative feelings (14.5%), bullying (5.2%), and wanting to die (4.3%).

The results indicated that the prevalence of suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury behaviors is high among adolescents and young people, with almost half having thoughts about death and a third thoughts about harming themselves. Both types of behavior co-occur in about a quarter of participants, while the contagion effect of self-injury was found in one third of participants.

Prevalence of suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury according to adverse life events

Of total study participants, 53.44% had experienced adverse life events. Among them, 62.60% were girls and the rest were boys. The prevalence of suicidal ideation was 30.93% in the group without adverse life events and 62.28% in the group with; the differences found were significant (χ2 (2) = 88.93, p < .001). For suicidal planning, the prevalence was 19.24% in the group without experience of adverse life events and 53.29% in the group with; these differences were significant (χ2 (2) = 86.41, p < .001). For suicidal attempts, the prevalence was 3.78% in the group that had not experienced adverse life events and 20.96% in the group that had (χ2 (1) = 40.68, p < .001). Regarding non-suicidal self-injury ideation, significant between-group differences (χ2 (1) = 87.13, p < .001) were also found with a prevalence of 11.34% in the group without experience of adverse life events and 45.51% in the group with. For non-suicidal self-injury attempts, the prevalence was 4.47% in the group that had no experience of adverse life events and 31.74% in the group that did (χ2 (1) = 75.02, p < .001).

The prevalence of suicide and self-injury increases considerably when young people have experienced an adverse life event. Alarmingly, rates of suicide attempts were as high as 21% in young people with adverse life events, while non-suicidal self-injury behavior rates were 32%.

Prevalence of suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury according to specific types of adverse life events

Table 1 shows the distribution of specific types of adverse life events and the percentage of girls versus boys, and adolescents versus young adults who reported having experienced any adverse life event. The most reported types of adverse life events were witnessing self-injury of friends, eating behavior problems, concern about sexual orientation, physical abuse, and sexual abuse. The chi-squared test showed significant gender differences for types of adverse life events (χ2 (10) = 47.33, p < .001). Girls had experienced more specific adverse life events than boys, mainly sexual abuse and eating behavior problems, whereas boys reported a higher prevalence of concern about sexual orientation and physical abuse. On the other hand, young adults reported a slightly higher prevalence of adverse life events than adolescents, except in physical abuse, but no significant differences were found between either age group in the type of adverse life event experienced (χ2 (10) = 15.35, p = .120). Only the most frequent adverse life events were included in further analyses. Witness to a family member’s self-injury, feeling lonely, psychological abuse, depression, or various adverse life events were not analyzed separately due to an insufficient number of cases.

Witnessing self-injury by friends was the most frequent adverse event for boys and girls of either age group. Physical abuse also showed a high prevalence in both genders, but girls experienced more eating behavior problems and boys were more concerned about sexual orientation.

Differences in suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury for type of adverse life event by gender

Two-way MANOVA was applied to analyze the differences in suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury between the different types of adverse life events, according to gender. The multivariate test revealed a significant marginal effect of type of adverse life event (F(20,985) = 1.53, Wilks’ Λ = 0.904, p = .064, η2 = 0.025), whereas the gender effect on suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury (F(5,297) = 0.75, Wilks’ Λ = 0.988, p = .585, η2 = 0.012) and interaction (F(20,985) = 1.29, Wilks’ Λ = 0.918, p = .178, η2 = 0.021) was not significant. The univariate analysis showed differences between the different types of adverse life events in all the indicators of suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury, suicidal ideation (F(4,310) = 3.99, p < .01, η2 = 0.050), suicidal planning (F(4,310) = 74.37, p < .01, η2 = 0.055), suicidal attempts (F(4,310) = 3.91, p < .01, η2 = 0.049), non-suicidal self-injury ideation (F(4,310) = 3.98, p < .01, η2 = 0.050), and non-suicidal self-injury attempts (F(4,310) = 2.81, p < .05, η2 = 0.036). According to the Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons, participants who had experienced physical, or sexual abuse reported more suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury than those who had witnessed self-injury. Also, participants who had experienced sexual abuse showed more non-suicidal self-injury attempts than those who had experienced sexual orientation, or eating behavior problems. In addition, participants who had experienced eating behavior problems showed more suicidal planning than those who had witnessed self-injury (Table 2).

The interaction effect between gender and type of adverse life event was also statistically significant for suicidal ideation (F(4,310) = 2.57, p < .05, η2 = 0.033) and suicidal attempts (F(4,310) = 2.40, p < .05, η2 = 0.031). Boys who had experienced sexual abuse had more suicidal ideation than girls (t(19) = 3.32, p < .01), but there were no significant differences between either gender in suicidal attempts. Girls who had experienced physical abuse had more suicidal ideation (t(27.72) = -2.72, p < .05) and suicidal attempts (t(43.05) = -2.17, p < .05) than boys. There were no significant gender differences in suicidal ideation, or suicidal attempts for concern about sexual orientation, eating behavior problems, or witnessing self-injury. Figures 1 and 2 display the interaction between gender and type of adverse life event for suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts.

Overall, adolescents and young people who had experienced sexual or physical abuse reported more risk of suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury than those who had experienced other adverse situations. In addition, boys who had experienced sexual abuse and girls who had experienced physical abuse were more at risk of suicide, but no differences were observed in self-injury as a function of gender or type of adverse event.

Differences of suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury for type of adverse life event by age

In this MANOVA, the different types of adverse life events and age were included as factors. The multivariate test revealed a significant effect of type of adverse life event (F(20, 996) = 1.48, Wilks’ Λ = 0.884, p < .01, η2 = 0.031) and a significant marginal interaction (F(20, 996) = 1.48, Wilks’ Λ = 0.907, p = .079, η2 = 0.024), whereas the age effect on suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury (F(5,300) = 0.85, Wilks’ Λ = 0.986, p = .513, η2 = 0.014) was not significant. The univariate analysis showed differences between the types of adverse life events in all the indicators of suicidality (suicidal ideation (F(4,313) = 3.33, p < .05, η2 = 0.042), suicidal planning (F(4,313) = 4.64, p < .001, η2 = 0.058), and suicidal attempts (F(4,313) = 2.94, p < .05, η2 = 0.037), whereas only significant differences were found in non-suicidal self-injury attempts (F(4,313) = 4.92, p < .001, η2 = 0.061) (Table 3).

The interaction effect between age and type of adverse life event was only statistically significant for non-suicidal self-injury attempts (F(4,313) = 3.69, p < .01, η2 = 0.046). Young adults who had experienced sexual abuse showed more non-suicidal self-injury attempts than adolescents who had experienced the same (t(16) = -3.77, p < .01). Similarly, young adults who had witnessed a friend’s self-injury reported more non-suicidal self-injury attempts than adolescents in the same situation (t(22.07) = -2.12, p < .05). However, adolescents who experienced eating problems reported more non-suicidal self-injury attempts compared to young adults (t(33.94) = 2.93, p < .01). Figure 3 shows the interaction between age and non-suicidal self-injury attempts.

All adolescents and young adults who had experienced adverse life events showed high rates of suicidality, but there were no significant differences between them in terms of adverse life event and age. However, self-injury attempts were more likely to occur in young people who had experienced sexual abuse or witnessed self-injury in friends than in adolescents, while adolescents with eating problems were more prone to self-injury than young people.

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to distinguish how adverse life events were associated with different indicators of suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury in the adolescent and young adult population according to gender and age. The results showed a higher prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury attempts than suicidal attempts (19% vs. 13%, respectively), although suicidal ideation (47.6%) was higher than non-suicidal self-injury ideation, or non-suicidal self-injury attempts. Prevalence rates for suicidality were around 4.1% higher than those reported in other western countries and in other studies of Spanish adolescents (Fonseca et al., 2018). However, the rates of non-suicidal self-injury attempts were lower than in other samples of young Spaniards by around 24.6% (Pérez et al., 2021). The co-occurrence of non-suicidal self-injury and suicidality varied depending on whether it was thought (ideation) or behavior (attempt), and was around 10% and 25%, respectively. In other studies, the co-occurrence between non-suicidal self-injury and suicidality is between 7.7% and 17.9% (Poudel et al., 2022; Voss et al., 2020). However, the co-occurrence between the different components of suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury has not been analyzed separately.

Adverse life events, as well as gender and age, modulated the rates of suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury. In our study, more than half the young adults reported having experienced some adverse life event, thereby doubling, or even multiplying by five, or seven times the risk of suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury, respectively, compared with young adults with no experience of adverse life event. These results are consistent with previous research that found a prevalence of suicidal attempts in adolescents’ exposure to adverse childhood situations of 6.3% versus 1.9% for those who had none (Miché et al., 2020).

Gender differences in the type of adverse life event experienced by boys and girls were found to have a differential impact on suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury behaviors. More girls than boys reported experiencing adverse situations. In addition, while girls reported more eating behavior problems and sexual abuse, boys reported more physical abuse and sexual orientation problems. Previous research has found higher prevalence rates of child sexual abuse (Cashmore & Shackel, 2014) and more eating disorders (Smink et al., 2014) for girls than boys. Eating disorders may be a risk factor for suicidality specific to women, while for men it is externalizing disorders (Miranda-Mendizabal et al., 2019). It should also be noted that boys are more likely than girls to disclose information about suicidal thoughts and behaviors that occurred in the previous year (Knorr et al., 2023).

In our study, the adverse life events most often associated with suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury for both boys and girls were sexual and physical abuse compared to witnessing self-injury. These results concur with those reported by Baiden et al. (2017), who found higher rates of non-suicidal self-injury in children and adolescents who had been physically and sexually abused. However, in our study a differential pattern was observed for boys and girls who had experienced physical and sexual abuse in suicidality. Suicidal ideation was more frequent in boys than in girls who had experienced sexual abuse, while suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts were higher for girls than for boys who had experienced physical abuse. Interestingly, although boys reported more physical abuse and girls more sexual abuse, the reverse pattern was associated with suicidality. Some studies indicate that in conditions of discrimination, girls have more suicidal ideation than boys (Vargas et al., 2021). In addition, cognitive variables, such as intolerance to uncertainty and anomalous perception of reality have been shown to be related to suicidal ideation in girls (Moreno-Mansilla et al., 2022).

On the other hand, age and type of adverse life event experienced were associated with non-suicidal self-injury attempts but not suicidality. Young adults were found to have experienced more sexual abuse and eating behavior problem than adolescents, whereas adolescents experienced more physical abuse. Specifically, in eating problems, adolescents reported more non-suicidal self-injury attempts than young adults. Among the participants who had experienced sexual abuse and witnessed self-injury, young adults reported more non-suicidal self-injury attempts than adolescents. Other studies have also found higher rates of physical, emotional, or sexual abuse before the age of 18 in adolescents who self-reported non-suicidal self-injury compared to those without non-suicidal self-injury (Wong & Chung, 2023; Zetterqvist et al., 2018). Also, some studies have found that the effects of stressful experiences, or general distress on non-suicidal self-injury did not differ by age, or gender (Hamza et al., 2021; Wilkinson et al., 2022). Therefore, the type of stressful situation must be considered. The intensity and chronicity of the adverse situation and the way in which the young adult perceives it may have a greater, or lesser influence on non-suicidal self-injury and even on suicidality. Our finding is of great interest as it may indicate that there is a critical age at which the adolescent and young adult population begin to think about the possibility of harming themselves, which could coincide with the time they begin to experience adverse life events.

These findings support the distinction between suicidal and self-injurious behaviors, as well as the differences between suicidal ideation and suicidal attempts, as proposed by the four-factor motivational–volitional model (Branley-Bell et al., 2019; O’Connor et al., 2013). Young adults who engage in non-suicidal self-injury, or suicidal behavior may differ in their motives and risk factors that lead them to engage in such harmful behaviors. For instance, it has been proposed that experiential avoidance could explain suicidal behavior to a greater extent than non-suicidal self-injury behavior (Angelakis & Gooding, 2021). In suicidal behavior, experiential avoidance occurs to escape the feeling of being trapped. On the other hand, in the case of non-suicidal self-injury, this avoidance is due to low tolerance of negative emotions, or cognitions and lack of control of high emotionality, using self-harm as a strategy to cope with negative emotions (Plener et al., 2018). Victimization and core self-evaluation have been shown to be intimately interrelated, which affects non-suicidal self-injury (Wang et al., 2023).

Ordóñez-Carrasco et al. (2023) found that the variables of theoretical models on suicide most involved in suicidal ideation are defeat, perceived burden, and psychological pain. Although previous studies have suggested the contagious effect of non-suicidal self-injury in young adults who witness these behaviors (Syed et al., 2020), in our study it seems that other adverse events, such as sexual or physical abuse, had a greater incidence on these non-suicidal self-injury behaviors than the mere observation of them. Probably, the fact that participants are young people who have recently experienced, or are experiencing, these adverse life events may have generated this negative emotional state, and they use non-suicidal self-injury to alleviate this distress. Adverse life events can act as that negative affective state that leads to non-suicidal self-injury, or even as a chronic life circumstance that traps the young adult ‘in a dead end’ leading to suicidal ideation, or suicidal attempts.

These findings must be taken with caution in light of several limitations. First, the participants are not representative of the adolescent and young adult population, hence the results cannot be generalized. In fact, the young adult sample was underrepresented compared with the adolescent sample. Second, although we analyzed frequent adverse life events for adolescents and young participants, other situations could not be analyzed due to small sample size. Also, when some adverse life events were analyzed based on age and gender, some adverse events were underrepresented, such as sexual, or physical abuse. Additionally, adverse life events were assessed through self-report, which has an inherent bias. A more rigorous assessment of adverse life events would include an interview as well as external confirmation. Third, only one risk factor, such as adverse situations, has been analyzed, modulated by age and gender. However, suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury behaviors are more complex and require further study. Research into functional expectations, difficulties associated with these behaviors, and health consequences will lead to a richer understanding of the etiology of these behaviors.

Adverse situations in early developmental stages have been shown to be linked to epigenetic and behavioral factors (Hays-Grudo et al., 2021). This research has found that adverse experiences can trigger suicidal and self-harming risk behaviors. Therefore, it is particularly important to underline the nurturing, education, health, and policy implications for addressing the impact of trauma and promoting the protection of children from threatening situations (Hink et al. 2022). In this sense, it is useful for children to be raised in an enriching environment where healthy caring relationships are strengthened, and resources are available to manage potential problem situations. Promoting secure attachment and resilience can be compensatory mechanisms to reduce or disrupt adverse situations. Additionally, training plans for professionals are necessary for the early detection of possible indicators of neglect, abuse, or other adverse situations that could expose children to risk. Educators can incorporate knowledge about trauma and suicide risk factors into their curricula, including teaching coping skills, stress management techniques, and providing information about how to seek help. This empowers students to recognize and address their own mental health needs and those of others. On the other hand, mental health professionals can use research findings to improve the effectiveness of interventions and develop tailored prevention strategies, such as early intervention programs or crisis intervention training. Screening tools and assessment protocols can also be implemented to identify individuals who may be at risk, contributing to the development of more holistic approaches to mental health and well-being. In terms of public policy, research findings should be exploited to develop evidence-based policies aimed at preventing trauma and reducing suicide rates. This may involve allocating resources for mental health services, implementing trauma-informed care practices in various institutions, or establishing support programs for vulnerable populations.

Conclusion

Adverse life events have been shown to have an impact on suicidal and self-injurious risk according to age and gender. The findings of this research highlight the importance of furthering the study of the adverse life situations experienced by adolescents and young people. This study has identified that around 50% of adolescents and young people have experienced adverse situations, such as friends who self-harm, concerns about sexual orientation, eating problems, or physical or sexual abuse. Girls experienced more sexual abuse and eating problems, and boys experienced more physical abuse and concerns about sexual orientation. These adverse events were associated with a higher risk of suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury behaviors. Sexual abuse appeared to be associated with suicidal ideation for boys, while suicidal ideation and attempts were related to physical abuse for girls. Additionally, significant differences were observed between adolescents and young people in non-suicidal self-injury. Young people with a higher risk of non-suicidal self-injury attempts had suffered sexual abuse or had friends who self-harmed, while eating problems was a risk factor for non-suicidal self-injury attempts in adolescents.

The type of adverse life events experienced by adolescents and young adults has been shown to be gender-specific and to have a differential impact on suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury risk. Various reasons were identified as underlying non-suicidal self-injury behaviors related mainly to the difficulty in addressing personal or family problems, or in managing negative feelings, which may contribute to the use of self-harm as a strategy for coping with negative emotions. However, whether these reasons differ from those underlying the risk of suicide, which were not analyzed, requires further research. These results contribute to new knowledge about the type of life events that have the greatest impact on suicide and self-injury risk for boys and girls in different developmental periods. The maturation process of boys and girls does not follow the same course, and the type of events they experience may also differ from one another and require a differential approach. It is therefore necessary to continue exploring how age and gender affect suicidal and self-injurious behaviors.

Future research should focus on training caregivers and educators in the early detection of situations that cause concern for adolescents. Identification of the mechanisms underlying the relationship between adverse life events and suicidality through longitudinal research designs will allow us to understand which personal, family, and social factors mediate this relationship and contribute to exacerbating the problem. Intervention strategies should aim to prevent these events from occurring and/or to mitigate the effect they have on young people at the time of occurrence. The various nurturing, educational, social, clinical, and political areas should work together to adopt different strategies that prevent exposure to adverse life events, provide adolescents and young people, families and professionals with resources to effectively address these situations and, subsequently, reduce the risk of suicidal and non-suicidal self-injury behaviors. In this manner, improving empathic communication or recommending professional help will enable young people to address social-emotional problems and empower them with coping strategies to deal with current problems.

References

Andover, M. S., Morris, B. W., Wren, A., & Bruzzese, M. E. (2012). The co-occurrence of non-suicidal self-injury and attempted suicide among adolescents: Distinguishing risk factors and psychosocial correlates. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 6(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-6-11.

Angelakis, I., & Gooding, P. (2021). Experiential avoidance in non-suicidal self‐injury and suicide experiences: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 51(5), 978–992. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12784.

Baiden, P., Stewart, S. L., & Fallon, B. (2017). The role of adverse childhood experiences as determinants of non-suicidal self-injury among children and adolescents referred to community and inpatient mental health settings. Child Abuse & Neglect, 69, 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.04.011.

Blasco, M. J., Vilagut, G., Almenara, J., Roca, M., Piqueras, J. A., Gabilondo, A., Lagares, C., Soto-Sanz, V., Alayo, I., Forero, C. G., Echeburúa, E., Gili, M., Cebrià, A. I., Bruffaerts, R., Auerbach, R. P., Nock, M. K., Kessler, R. C., & Alonso, J. (2019). Suicidal thoughts and behaviors: Prevalence and association with distal and proximal factors in Spanish university students. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 49(3), 881–898. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12491.

Branley-Bell, D., O’Connor, D. B., Green, J. A., Ferguson, E., O’Carroll, R. E., & O’Connor, R. C. (2019). Distinguishing suicide ideation from suicide attempts: Further test of the Integrated Motivational-Volitional Model of suicidal Behaviour. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 117, 100–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.07.007.

Carli, V., Hoven, C. W., Wasserman, C., Chiesa, F., Guffanti, G., Sarchiapone, M., Apter, A., Balazs, J., Brunner, R., Corcoran, P., Cosman, D., Haring, C., Iosue, M., Kaess, M., Kahn, J. P., Keeley, H., Postuvan, V., Saiz, P., Varnik, A., & Wasserman, D. (2014). A newly identified group of adolescents at invisible risk for psychopathology and suicidal behavior: Findings from the SEYLE study. World Psychiatry, 13(1), 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20088.

Cashmore, J., & Shackel, R. (2014). Gender differences in the context and consequences of child sexual abuse. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 26(1), 75–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.2014.12036008.

Cipriano, A., Cella, S., & Cotrufo (2017). Nonsuicidal self-injury: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1946. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01946.

Ehlers, C. L., Yehuda, R., Gilder, D. A., Bernert, R., & Karriker-Jaffe, K. J. (2022). Trauma, historical trauma, PTSD and suicide in an American Indian community sample. Journal of Psychiatry Research, 156, 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.10.012.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8.

Fonseca Pedrero, E., & de Pérez, A. (2020). Evaluation of suicidal behavior in adolescents: The paykel suicide scale. Papeles Del Psicólogo, 41, 106–115. https://doi.org/10.23923/pap.psicol2020.2928.

Fonseca-Pedrero, E., Inchausti, F., Pérez-Gutiérrez, L., Aritio, R., Ortuño-Sierra, J., Sánchez-García, M. A., Lucas, B., Domínguez, M. C., Foncea, D., Espinosa, V., Gorría, A., Urbiola-Merina, E., Fernández, M., Merina, C., Gutiérrez, C., Aures, M., Campos, M. S., & Domínguez-Garrido, E. (2018). Suicidal ideation in a community-derived sample of Spanish adolescents. Revista De Psiquiatría Y Salud Mental, 11, 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsmen.2018.02.008. & Pérez de Albéniz.

Fonseca-Pedrero, E., Al-Halabí, S., Pérez-Albéniz, A., & Debbané, M. (2022). Risk and protective factors in adolescent suicidal behaviour: A network analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1784. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031784.

Fumero, A., Marrero, R. J., Perez-Albeniz, A., & Fonseca-Pedrero, E. (2021). Adolescents’ bipolar experiences and suicide risk: Well-being and mental health difficulties as mediators. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18, 3024. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063024

Gámez-Guadix, M., Mateos-Pérez, E., Wachs, S., & Blanco-González, M. (2022). Self-harm on the internet among adolescents: Prevalence and association with depression, anxiety, family cohesion, and social resources. Psicothema, 34(2), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2021.328.

Hamza, C. A., Goldstein, A. L., Heath, N. L., & Ewing, L. (2021). Stressful experiences in university predict non-suicidal self-injury through emotional reactivity. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1209. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.610670.

Hays-Grudo, J., Morris, A. S., Ratliff, E. L., & Croff, J. M. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences and addiction. In J. M. Croff, & J. Beaman (Eds.), Family Resilience and Recovery from opioids and other addictions (pp. 91–108). Springer.

Horváth, L. O., Győri, D., Komáromy, D., Mészáros, G., Szentiványi, D., & Balázs, J. (2020). Nonsuicidal self-injury and suicide: the role of life events in clinical and non-clinical populations of adolescents. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 370. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00370.

Hink, A. B., Killings, X., Bhatt, A., Ridings, L. E., & Andrews, A. L. (2022). Adolescent suicide—understanding unique risks and opportunities for trauma centers to recognize, intervene, and prevent a leading cause of death. Current Trauma Reports, 8, 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40719-022-00223-7.

Knorr, A. C., Frisch, J. V., Fitzsimmons, K., & Ammerman, B. A. (2023). College student experiences of past-year suicidal thoughts and behaviors: Gender differences by institution type. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04826-4.

Liu, R. T., Scopelliti, K. M., Pittman, S. K., & Zamora, A. S. (2018). Childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry, 5(1), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30469-8.

Marrero, R. J., Bello, M., Morales-Marrero, D., & Fumero, A. (2023). Emotion regulation difficulties, family functioning, and well-being involved in non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal risk in adolescents and young people with borderline personality traits. Children, 10, 1057. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10061057.

Miché, M., Hofer, P. D., Voss, C., Meyer, A. H., Gloster, A. T., Beesdo-Baum, K., Wittchen, H. U., & Lieb, R. (2020). Specific traumatic events elevate the risk of a suicide attempt in a 10-year longitudinal community study on adolescents and young adults. European Child &Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(2), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01335-3.

Miranda-Mendizabal, A., Castellví, P., Parés-Badell, O., Alayo, I., Almenara, J., Alonso, I., Blasco, M. J., Cebrià, A., Gabilondo, A., Gili, M., Lagares, C., Piqueras, J. A., Rodríguez-Jiménez, T., Rodríguez-Marín, J., Roca, M., Soto-Sanz, V., Vilagut, G., & Alonso, J. (2019). Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. International Journal of Public Health, 64(2), 265–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-018-1196-1.

Moreno-Mansilla, S., Ricarte-Trives, J. J., & Barry, T. J. (2022). The role of transdiagnostic variables within gender differences in adolescents’ self reports of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Psicothema, 35(1), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2022.153.

Nock, M. K. (2010). Self-injury. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 339–363. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258.

O’Connor, R. C., Rasmussen, S., Miles, J., & Hawton, K. (2009). Self-harm in adolescents: Self-report survey in schools in Scotland. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 194(1), 68–72. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.047704.

O’Connor, R. C., Smyth, R., Ferguson, E., Ryan, C., & Williams, J. M. G. (2013). Psychological processes and repeat suicidal behavior: A four-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81, 1137–1143. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033751.

Ordóñez-Carrasco, J. L., Sayans-Jiménez, P., & Rojas-Tejada, A. J. (2023). Ideation-to-action framework variables involved in the development of suicidal ideation: A network analysis. Current Psychology, 42, 4053–4064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01765-w.

Paykel, E. S., Myers, J. K., Lindenthal, J. J., & Tanner, J. (1974). Suicidal feelings in the general population: A prevalence study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 214, 460–469. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.124.5.460.

Pérez, S., García-Alandete, J., Gallego, B., & Marco, J. H. (2021). Characteristics and unidimensionality of non-suicidal self-injury in a community sample of Spanish adolescents. Psicothema, 33, 251–258. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2020.249.

Perkins, N. M., Ortiz, S. N., Smith, A. R., & Brausch, A. M. (2021). Suicidal ideation and eating disorder symptoms in adolescents: The role of interoceptive deficits. Behavior Therapy, 52(5), 1093–1104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2021.03.005.

Peters, J. R., Mereish, E. H., Krek, M. A., Chuong, A., Ranney, M. L., Solomon, J., Spirito, A., & Yen, S. (2020). Sexual orientation differences in non-suicidal self-injury, suicidality, and psychosocial factors among an inpatient psychiatric sample of adolescents. Psychiatry Research, 284, 112664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112664

Plener, P. L., Kaess, M., Schmahl, C., Pollak, S., Fegert, J. M., & Brown, R. C. (2018). Nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescents. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 115(3), 23. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2018.0023.

Poudel, A., Lamichhane, A., Magar, K. R., & Khanal, G. P. (2022). Non suicidal self injury and suicidal behavior among adolescents: Co-occurrence and associated risk factors. Bmc Psychiatry, 22(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03763-z.

Rajhvajn Bulat, L., Sušac, N., & Ajduković, M. (2023). Predicting prolonged non-suicidal self-injury behaviour and suicidal ideations in adolescence–the role of personal and environmental factors. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04404-8.

Sahle, B. W., Reavley, N. J., Li, W., Morgan, A. J., Yap, M. B. H., Reupert, A., & Jorm, A. F. (2022). The association between adverse childhood experiences and common mental disorders and suicidality: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 1489–1499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-021-01745-2.

Smink, F. R., van Hoeken, D., Oldehinkel, A. J., & Hoek, H. W. (2014). Prevalence and severity of DSM-5 eating disorders in a community cohort of adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(6), 610–619. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22316.

Smith, L., Shin, J. I., Carmichael, C., Oh, H., Jacob, L., López-Sánchez, G. F., Tully, M. A., Barnett, Y., Butler, L., McDermott, D. T., & Koyanagi, A. (2021). Prevalence and correlates of multiple suicide attempts among adolescents aged 12–15 years from 61 countries in Africa, Asia, and the Americas. Journal of Psychiatry Research, 144, 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.09.047.

Soullane, S., Chadi, N., Low, N., Ayoub, A., & Auger, N. (2022). Relationship between suicide attempt and medical morbidity in adolescent girls. Journal of Psychiatry Research, 155, 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.08.002.

Swannell, S. V., Martin, G. E., Page, A., Hasking, P., & St John, N. J. (2014). Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta‐analysis and meta‐regression. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 44(3), 273–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12070.

Syed, S., Kingsbury, M., Bennett, K., Manion, I., & Colman, I. (2020). Adolescents’ knowledge of a peer’s nonsuicidal self-injury and own non‐suicidal self‐injury and suicidality. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 142(5), 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13229.

Vargas, S. M., Calderon, V., Beam, C. R., Céspedes-Knadle, Y., & HueyJr, S. J. (2021). Worse for girls? Gender differences in discrimination as a predictor of suicidality among latinx youth. Journal of Adolescence, 88, 162–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.02.007.

Voss, C., Hoyer, J., Venz, J., Pieper, L., & Beesdo-Baum, K. (2020). Non‐suicidal self‐injury and its co‐occurrence with suicidal behavior: An epidemiological‐study among adolescents and young adults. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 142(6), 496–508. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13237.

Wang, Z., Wang, X., Peng, Y., Liu, C., & He, J. (2023). Recalled childhood maltreatment and suicide risk in Chinese college students: The mediating role of psychache and the moderating role of meaning in life. Journal of Adult Development, 30, 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-022-09422-7.

Wang, S., Ding, W., Song, S., Tan, Y., Ahmed, M. Z., Xie, R., & Li, L. (2023a). The relationship between adolescent victimization, nonsuicidal self-injury, and core self-evaluation: A cross-lagged study. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-05299-1.

Wilkinson, P. O., Qiu, T., Jesmont, C., Neufeld, S. A., Kaur, S. P., Jones, P. B., & Goodyer, I. M. (2022). Age and gender effects on non-suicidal self-injury, and their interplay with psychological distress. Journal of Affective Disorders, 306, 240–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.03.021.

Wong, S. L., & Chung, M. C. (2023). Child abuse and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese university students: The role of emotion dysregulation and attachment style. Current Psychology, 42, 4862–4872. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01832-2.

Xu, H., Jiang, Z., Li, S., Zhang, X., Xu, S., Wan, Y., & Tao, F. (2022). Differences in influencing factors between non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts in Chinese adolescents: The role of gender. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 870864. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.870864.

Zetterqvist, M., Svedin, C. G., Fredlund, C., Priebe, G., Wadsby, M., & Jonsson, L. S. (2018). Self-reported nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) and sex as self-injury (SASI): Relationship to abuse, risk behaviors, trauma symptoms, self-esteem and attachment. Psychiatry Research, 265, 309–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.05.013.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author R.J.M. designed the study and wrote the original draft. Author A.F. reviewed and edited the manuscript. Author E.M.B. managed the literature searches and designed the tables and figures and author D.M. undertook the statistical analysis and checked the references. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Marrero, R.J., Bello, E.M., Morales-Marrero, D. et al. Distinguishing the role of adverse life events in suicidality and non-suicidal self-injury in Spanish adolescents and young adults. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05883-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05883-z