Abstract

The purpose of the study was to investigate impact of dancing program on early childhood children’s pro-social skills, aggression and shyness. Treatment group applied eight weeks long dancing program which contained two dance activities for each week. Control group had not applied the dance program. Forty-five children from treatment and 62 children from control group participated the study. Teachers rated their children’s social skills before and after the dancing program. Findings showed that treatment children’s pro-social skills significantly increased from pretest to posttest and aggression and shyness scores significantly decreased from pretest to posttest. Similar findings were not detected for control group. Two groups’ posttest minus pretest differences for three sub dimension compared and comparison revealed significant difference in favor of treatment group. These findings pointed the dancing program which was developed by investigators as a practical intervention tool to promote young children’s social skills.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Ethnographical and anthropological studies showed that dance is common human behavior that is detected in almost every culture (Fink et al., 2021; Marett, 2020; Mead, 2015). Scholars claimed that dance might have evolved as medium for transferring emotional and social information among group members (Fink et al., 2021; Sevdalis & Keller, 2011). Synchronization of movements of dancer facilitate demonstration of prosocial behaviors such as helping and sharing (Tomasello, 2020). For the purpose of the current study we defined social skills for children as being able to build appropriate relationships with others (aggression), defining and displaying him/herself in a developmentally appropriate ways (shyness) and displaying positive attitudes and actions (pro-social skills) such as helping, sharing, being compatible, benevolence, that enable sustainability of child’s social relation and personal well-being” (Balcı et al., 2021).

Throughout decades’ plethora of studies have revealed impacts of children’s social skills on many aspects of development such as psychological well-being, academic achievement, school adjustment, peer acceptance (Chen et al., 2013; Gou et al., 2018; Miles & Stipek, 2006; Teo et al., 1996; Yang et al., 2014). Teo et al. (1996) conducted very comprehensive 17-year longitudinal study about the impact of social skills on academic achievement. They have found that social skills in the first three years of life predicted achievement in elementary school. Social skills were predictor of academic achievement even after controlling for IQ. This impact extended until sixth grade. More recent studies defined pro-social skills such as helping, sharing, showing solidarity as sub dimension of social skills. Prosocial skills have a strong positive impact on academic achievements (Capara et al., 2000), experiencing positive feelings (Paulus & Moore, 2017), and building social networks (Sunar & Fidancı, 2016). In a recent comprehensive study Gustavsen (2017) worked with 2266 Norwegian school children first grade through eighth grade. His findings were in line with Teo et al. he also detected children’s pro-social skills as significant contributor to their academic achievement. Gou et al. (2018) reached similar results with 456 elementary school children (mean age 11.06). Their findings also pointed social skills as a significant predictor of children’s academic achievement.

Beside academic achievement social skills contributed to better social, psychological and school adjustment (Miles & Stipek, 2006). Several studies pointed aggressiveness as inhibitory factor for children’s adjustment (Miles & Stipek, 2006; Yang et al., 2014). Yang et al. (2014) conducted a study with 1171 elementary school children. Their findings revealed association between aggression and children’s social, school and psychological adjustment. The study showed that children did not prefer aggressive peers for friendship and leadership. They also found that aggressive children experience loneliness and victimization more than their none aggressive peers. Since their aggression awakened unpleasant emotions in other children aggressive children lived difficulty in school adjustment. Aggressive children are subject to negative experiences such as peer rejection, stigmatization, isolation (Yang et al., 2014).

Beside aggression shyness caused problems too (Chen et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2015). Chen et al. (2013) conducted longitudinal study on the relation between shyness and behavioral problems of 1171 Chinese children with mean age of 9 years. They have found that shyness contributed to loneliness, child depression, teacher-rated internalizing problems and adjustment problems. In another study Yang et al. (2015) found that shyness had negative impact on elementary school children’s peer relationships, academic achievement and psychological well-being. Shy children experienced significantly more psychological distress and poorer peer relations than children that were not shy (Yang et al., 2015). These studies revealed the impact of pro-social skills, aggression and shyness on several aspects of children’s development.

How do the mechanism work? Scholars claimed that children with good social skills developed closer relations with their teacher and classmates thus in return they adjust better to the school environment. Therefore, children with good social skills lived positive early experiences in the school environment which enabled them to build stronger relationships with their teachers and peers (Gou et al., 2018; Miles & Stipek, 2006). For example, starting from kindergarten children with good social skills created effective teacher-child relationship and positive impacts of these relations extended until third grade (Wu et al., 2018). This process can have created positive cycle that feed better social skills. Children who lack social skills cannot get support from their peers for academic, personal and psychological issues. Therefore, it is harder for them to adjust school and pursue successful academic life. Additional because of same reasons they might have been akin to psychological and emotional problems which indirectly impede academic achievement (Gou et al., 2018; Miles & Stipek, 2006; Wu et al., 2018).

All above mentioned studies revealed the importance of pro-social skills, aggressiveness and shyness for children’s development therefore intervention studies which aimed to increase social skills have been conducted (Gou et al., 2018). Studies attempted to increase children’s social skills through training detected positive impacts of intervention programs on children’s social skills (Ashdown & Bernard, 2012). For example, Ashdown and Bernard (2012) implied You Can Do It (YCDI) program which aimed to support kindergarteners’ social skills. The program lasted 10 weeks and it contained three 20-min lessons per week. They found children in the program group displayed significantly higher improvements on social-emotional competence such as positive self-orientation, positive other-orientation, and positive work-orientation and social skills such as co-operation, assertion, and self-control and positive social-emotional well-being such as the presence of positive emotions and behaviors, and the absence of negative emotions and behaviors than their peers who were not in the program group. Since dancing is a social milieu which can contain both social interaction and individual performances (Zachopoulou et al., 2004) we thought that a systematic dancing program can be used as an intervention to improve children’s social skills.

Dance and social skills

Group dances, by their nature, require skills such as interpersonal interaction, harmony, waiting their turn, sharing and showing self-confidence because these are indispensable for a harmonious dance performance. Borowski (2021) conducted a comprehensive review about dance and development of social-emotional competence. He concluded that dance promoted social-emotional competences because it provided opportunities for self-intimation, nonverbal expression and synchrony. Several studies investigated impact of dance on children’s social skills (Biber, 2016; Lobo & Winsler, 2006; Panagiotopoulou, 2018; Pereira & Marques-Pinto, 2018). For example, Panagiotopoulou (2018) examined impact of dance therapy on high school students emotional and social skills. There were 11 students in experimental and 12 students in control group. He found that increase in experimental group’s social and emotional skills were significantly higher than control group’s social and emotional skills. Panagiotopoulou (2018) mentioned that experimental group’s group cohesion improved because children interacted with each other and started to care about the emotions of others in their groups.

Lobo and Winsler (2006) targeted early childhood children in their intervention study. They conducted an experimental study to test the impact of creative dance and movement program on social competence of 40 Head Start preschoolers. They randomly assigned children to dance and control groups. Their dance program involved body parts, balance, time, space, force, energy and acting themes. They have found significant increase for social skills of experimental group and significant decrease for behavioral problems. In a more recent study Biber (2016) investigated impact of folk dance training on 5–6 years’ children’s physical and social development. In his study a folk dance specialist worked with 20 children in experimental group for eight weeks. Dance group significantly increased in physical and social aspects. Although the increase of experimental group was higher than the increase of control group, the difference was not statistically significant.

All these studies revealed the positive impact of dancing on children’s social development. Lobo and Winsler (2006) pointed that they studied high risk population and there were need for studies with other groups. Biber (2016) used folk dances and recruited a folk dance specialist. Also the study did not compare groups. Biber (2016) just compared within groups pre-test and posttest scores. In the current study we did not target high risk population. Therefore, the study provided data about the impact of dance on early childhood children that were not from high risk population. Also our intervention prepared for teachers. Teachers were able to apply the intervention in their classroom without any exhausting preparation or training. The intervention included both group dances and individual performances. Therefore, we believed that it would be useful in developing pro-social skills and reducing personal negative social characteristics such as aggression and shyness. Our dance program developed systematically, taking into account the developmental characteristics of children, could improve children’s relevant skills. According to Rajan and Aker (2020), dance programs are not widely used in pre-school programs and are seen only in spare time in kindergartens. In this study, a systematic dance program is suggested as an intervention program for behaviors that negatively affect social skills, such as aggression and shyness, in kindergartens, and that such practices will be intensely important. Dance includes activities that follow people’s interests, such as music and games, considering the developmental characteristics of the preschool period. This feature makes it a useful tool for children to learn while having fun. Therefore, we believed that the current dancing intervention program is a practical educational tool for teachers. In addition, our dance program was designed to be suitable for the preschool classroom environment, making it an activity that could be integrated into the daily flow of the class program. To achieve this, question-and-answer sections related to the activities were included after the activities. In this regard, the dance program we developed differs from programs applied in previous studies.

Purpose of the study was to investigate impact of dancing program on early childhood children’s pro-social skills, aggression and shyness. Accordingly, the following questions will be tested: (1) Will dancing group children’s pro-social skills significantly increase and their aggression and shyness significantly decrease from pretest to posttest? (2) Will control group children’s pro-social skills significantly increase and their aggression and shyness significantly decrease from pretest to posttest? (3) Will dancing group and control group children pretest, posttest differences for pro-social, aggression and shyness significantly differ?

Methodology

The study was conducted with the permission of Harran University and Şanlıurfa Governorship, Turkiye. Permission dates and protocol number were 21.10.2022, E-78521740-300-174975. The purpose and the content of the study were announced through the City Representative of the Ministry of Nation Education and social media. Thus, volunteer teachers started to contact with researcher. From four schools 15 teachers agreed to participate the study. Volunteer teachers assigned as treatment group because although 15 teachers agreed to participate the study not all of them agreed to apply the dance program in their classroom because they thought it would be extra work and burden for them. Therefore, seven teachers from three schools consisted the treatment group. Since random assignment to treatment and control groups was not possible we recruited quasi-experimental design.

Participants

Teachers informed the parents about the study. Teachers evaluated social skills as pre and posttest of children whose parents signed inform consent letter. A total of eight teachers participated in the research, with three in the experimental group and five in the control group. All teachers had obtained their bachelor’s degrees in preschool education. The average age, professional experience, and years of education for the teachers in the experimental group were as follows: 32.66 years (SD = 2.3), 11 years (SD = 4.8), and 15.3 years (SD = 0.5), respectively. In the control group, the teachers had professional experience and education years of 31.2 (SD = 3.4) and 10.6 (SD = 5.4) years, respectively. The teachers were similar in age, had similar teaching experience, and professional education. No special skills were required to implement the dance program, as the activities within the program were presented to the teachers step by step in detail. One of the strengths of the program is that it is easy to implement for teachers and does not require additional skills or extensive training, apart from being a preschool teacher.

Originally, 84 parents from the treatment group and 66 from the control group consented their children to participate in the study. However, three classes in the treatment group from same school lost their technological devices (sound and video systems); therefore, they could not complete the program on time and we had to exclude 37 children from the study. Other than that during the measurement phase, some of the children did not want to participate, some of them could attend neither of the measurement processes and some of them were missing; therefore, 45 children from the treatment group and 62 from the control group ended the study. Finally, total of 107 children’s social skills evaluated by their teachers (Table 1).

Of the 45 children in the treatment group 25 (55.6%) were boys and 20 (44.4) were girls. Of the 62 children in the control group 36 (58.1%) were boys and 26 (41.9%) were girls. Table 2 presented descriptive characteristics of participating children. Table 2 revealed that two groups were coming somewhat similar socio-economical background.

Measures

Children’s social skills were measured with the Turkish version of Teacher Assessment of Social Behaviors Scale (TASBS) (Cassidy & Asher, 1992). The scale was adapted to Turkish by Seven (2010). It is a likert type scale with 12 items and contains three subscales: aggressive, prosocial, shy/withdrawn. The scale consists of six items for aggression, three for social skills, and three for shyness. Sample items for aggression are: This child starts fight. This child hurts other children. Sample items for prosocial behaviors are: This child collaborates with other children, shares, and waits their turn. This child is friendly and kind to other children. Sample items for shyness are: This child is shy and reserved. This child does not play or work with other children. Minimum and maximum scores can be obtained from the scale are 12 and 60 respectively.

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for pre and posttests of treatment group’s aggressiveness, prosocial, and shyness were 0.975, 0.959; 0.867, 0.916; and 0.863, 0.782 respectively. For the control group Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for pre and posttest aggressiveness, prosocial and shyness were 0.962, 0.954; 0.902, 0.886; and 0.435, 0.444 respectively. Most of these Cronbach’s coefficients are considered indicative of sound reliability for education (Isaac & Michael, 1995).

Procedure

After the teachers agreed to participate and parents signed consent letters, teachers filled TASBS for every child as a pretest. Parents responded to demographic questionnaire and provided information about their socio-economic status.

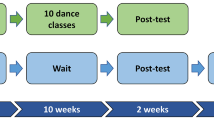

Following pretests researchers conducted a zoom meeting with treatment teachers. In the meeting researches explained key points about dance program and how to implement the program in their classroom. Dance program lasted eight weeks. There were two dance activities for every week. Each dance session lasted around 20–25 min. The dance program proceeded gradually from whole group dances to individual dances.

First six activities consisted of whole group dances. At the initial stage, whole group dances are included to increase familiarity and harmony among children. Additionally, introducing children to the idea of dancing is one of the objectives. It is believed that children seeing their teachers and all their classmates dancing will help them understand that dancing in class is a normal behavior for children. It is also thought that children moving in harmony with their friends will strengthen their bonds, reduce behaviors such as aggressiveness and shyness, and thus, promote prosocial behaviors such as sharing and helping (Borowski, 2021; Lobo & Winsler, 2006; Panagiotopoulou, 2018; Pereira & Marques-Pinto, 2018).

Following the whole group dances, the aim was for children to dance in smaller groups. Children danced in small groups or in pairs following five activities. The compositions of the small groups were changed in each dance activity. This provided children with the opportunity to perform together in small group (dance) work with all their classmates, aiming to bring them closer. For example, in the mirror dance, children imitated each other. It was thought that imitating others makes us feel closer to those who imitate us (Waal De, 2016), which would contribute to the closeness of the children’s relationships with each other. Additionally, before children danced individually in front of the larger group, the purpose was for them to rehearse in front of smaller groups and get accustomed to the idea of presenting their figures in front of others.

Finally, last five activities were allocated for individual and free dances where children could showcase their own personal figures were included. The goal was to enable children to confidently present their activities through dance without shyness. It was believed that dance, as a context where the child is in harmony with other children, would facilitate self-expression without shyness. Seeing that the child’s self-created figures are appreciated and not ridiculed by the classmates and teacher was thought to both reduce shyness and increase their sense of belonging to the group (Misch, 2016; Tomasello, 2015) which in return would reduce aggression.

Step by step detailed instruction and required songs, video clips provided by researches to treatment teachers. Examples for whole group, pair and individual dance activities presented below:

Week 1 Activity 2- Apple Worms. For warming up teacher and children sing and simultaneously dance the lyrics of “let hop, let jump and pick up apples from tree.” After that teacher starts to tell following story about apple worms. While they were wandering in the forest apple worm family find dried apples. Since apple is their favorite fruit they all got very happy. They decided to take these dried apples to their home and have an apple party.” At this point teacher cut the story. Teacher tell children “now we will be apple worm family, we will carry dried apples to home and have an apply party” Teacher and children dramatize the scenario by acting dance moves of “I am an apple worm” song.

After the activity teacher asked following questions: why apple worms were happy? Why do you think apple worms were moving together? How did you feel when you joined the party as an apple worm? What did you like best about the party?

Week 5 Activity 2- Mirror Dance. Teacher starts a chat about mirrors. Teacher tell children “Today we will do mirror dance. Everyone will pair with a friend and ask that friend to be his/her mirror. You will dance in front of your mirror; and your friend as your mirror will repeat your every move.” Teacher open a fast pace dancing music children takes turns and dance.

After the dance teacher asks following questions: What does mirror do? How did you feel while you were doing your own dance? Was it difficult to act like a mirror and imitate your friend’s dance moves? How do you feel when your friend repeated your dance moves?

Week 7 Activity 1- Butterflies. Teacher places flower pictures on classroom’s floor with different colors as many as number of children in class. Teacher puts a box which contains thin papers with different colors in the middle of the classroom. Teacher asks children a riddle about butterflies and provide hints until children find the answer. All together they look at several butterfly pictures. Teacher asks children “which is your favorite?” and then teacher gives following instruction “now I want you to imagine yourself as your favorite butterfly. You can dance among the flowers (points followers that teacher place on classroom floor) like butterflies. When you get tired you can rest on your flower and then continue to dance.” After the instruction teacher opens a slow music as children dance, teacher puts faster music. Thus, children freely dance and create their individual figures.

After the dance teacher asks following questions: If you were a butterfly where would you like to live? Have you ever seen a flying butterfly, what does it look like? How do you feel when you were dancing like a butterfly?

Results

Normality of pretest posttest scores for treatment and control group were calculated with Shapiro-Wilks test. Shapiro-Wilks test revealed that only pretest of treatment data was normally distributed. However, rest of the data (posttest treatment, pre and posttest control) were not normally distributed. Therefore, we used non-parametric Mann–Whitney U and Wilcoxon-test to analyze the data. For, all dependent variable we calculated effect size by dividing the square of the Z value to one minus sample size.

Between group data for three subtests were analyzed with series of Mann-Whitney U and within group data for three subtests were analyzed with series of Wilcoxon-test. Since there were a lot of individual tests conducted for statistical analyses we reported significant findings in detail. For all three sub dimensions of control group from pretest to posttest Wilcoxon-test did not show any significant differences.

Table 2 showed treatment and control groups’ mean scores. For treatment group Wilcoxon revealed statistically significant decreased aggressiveness scores from pretest to posttest (Z = = -3.339, p < 0.001). Wilcoxon also showed significant decreased in shyness scores from pretest to posttest (Z = = -3.822, p < 0.0001). Finally, for treatment group Wilcoxon displayed significant increase in prosocial skills from pretest to posttest (Z = 4.476, p < 0.000008). We have conducted same Wilcoxon analyzes for control group too. For the control group Wilcoxons did not show statistically significant among three sub dimensions’ pretests and posttest scores.

Pretests comparisons between treatment and control group showed that only significant difference between treatment (Mdn = 46.47) and control (Mdn = 59.47) groups appeared in prosocial sub dimension U = 1056, p = 0.031. This finding revealed that at the beginning of the study children in control group had significantly higher scores than children from treatment group for prosocial skills. For aggressiveness and shyness pretest comparison did not show significant difference between treatment and control groups.

Finally, we subtracted pretests scores from posttest scores and compared the differences with Mann–Whitney U Test. Significant difference appeared between treatment and control groups for all three sub dimensions. Mann–Whitney U Test indicated a significant difference between treatment (Mdn = 44.79) and control (Mdn = 60.69) groups’ differences for aggressiveness posttest minus pretest scores, U = 980.5, p = 0.006. Treatment groups’ children’s aggressiveness drop was significantly larger than control groups’ children’s aggressiveness drops from pretest to posttest. Mann–Whitney U Test indicated a significant difference between treatment (Mdn = 64.00) and control (Mdn = 46.74) groups’ differences for prosocial sub dimesion’s posttest minus pretest scores, U = 945.0, p = 0.004.This result told that treatment groups’ children’s prosocial skills evaluation increase was significantly higher than control groups’ children’s prosocial skills evaluation increase from pretest to posttest. Finally, Mann–Whitney U Test pointed a significant difference between treatment (Mdn = 41.86) and control (Mdn = 62.81) groups’ differences for shyness sub dimension’s posttest minus pretest scores, U = 848.0, p = 0.0004. This finding revealed that decrease in shyness from pretest to posttest was significantly higher in treatment group children than control group children.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate impact of dance program on young children’s pro-social behaviors, aggression and shyness. Findings revealed that contrary to control group dancing group had significant gains for pro-social behaviors and significant decrease in aggression and shyness. These findings are in line with former studies (Biber, 2016; Lobo & Winsler, 2006; Panagiotopoulou, 2018; Pereira & Marques-Pinto, 2018).

The current study provided hints on that dancing program supported development of children’s pro-social skills such as sharing, cooperating, waiting his/her turn, helpfulness. Concurrently, teachers in dancing group reported that their children’s aggressive behaviors showed significant decrease after the dancing program whereas no such evidence was present for control group. The characteristics of our dance program may have caused this result. In early weeks of the dancing program teachers applied groups dances which required children move together synchronously with each other and with the music. Some scholars pointed synchrony that is established during the dancing may have increased interpersonal bonding, cooperation because moving together in a harmony by imitating each other created sense of acquaintanceship, closeness and unity (Borowski, 2021; Fink et al., 2021).

Findings of Kirschner and Tomasello (2010) supported these claims. They conducted a study with 4-year-olds. In one group children interacted with one another and an adult while they were dancing, singing and playing percussion instruments. In the other group children pursued an activity while interacting with other however there were no dancing, singing and playing percussion instruments. After this phase, children participated two social interactions which required to help their partner and cooperate on a problem-solving task. Their findings indicated that compare to control group, singing, dancing and playing percussion group showed significantly higher levels of helping and cooperative behaviors. In a more recent experimental study Rabinowitch and Meltzoff (2017) found that experiencing rhythmic movement with their peers increased 4-year-olds’ sharing and fairness toward their peers. These studies revealed that synchronized movements such as dancing might have enhanced pro-social skills such as cooperating, helping, sharing which in return strengthened emotional bonds among group members. That might have been the reason for significant decrease in aggressive behaviors among dancing group. After all, displaying aggressive behavior to close ones is harder than acting aggressively to people that person does not feel emotional closeness (Kernberg, 1991; Lorenz, 2021).

The current study also provided some evidence pointing that our dancing program decreased young children’s shyness. To the authors’ knowledge this is the first study which provided findings on positive impact of dancing program on shyness. Again characteristics of our dancing program might have been the reason for this outcome. Our dancing program was inspired by book of Mead (2015) about Samoa. In the book she mentioned strict hierarchical, collectivist structure of the primitive community that did not provide adequate opportunity for youngsters to exhibit their individual existence. She pointed that only during dance gatherings youngster were allowed and encouraged to express their individuality. Inspiring by this idea while we were creating our dancing program we gradually decreased group dance and increased opportunities for individual performances. Our assumption was that early dance activities should help children get to know each other better and create feelings such closeness and companionship. Once this was achieved it would be easier for children to exhibit their individual performances in front of other children. Thus, this would help them to overcome their shyness.

Since several studies revealed that children’s shyness contributed to children’s social-emotional problems such as loneliness, depression, negative peer-relations and adjustment deficiencies (Chen et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2015) and negatively affect children’s academic achievement (Yang et al., 2015) we believed pointing out dancing as an early intervention mechanism for overcoming shyness is an important for all parties that are dealing with education and children’s development. In consideration of long term negative impacts of shyness (Chen et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2015) the value of this early intervention tool can be better understood. In summary, we believe that the dance program we have developed contributes to the improvement of children’s prosocial behaviors and helps reduce their aggressiveness and shyness. Therefore, we believe it can be considered for use in early childhood classrooms by teachers.

Limitations and future studies

Children’s social skills were measured through teacher ratings. Although measuring children’s social skills through teacher ratings is a common application (Chen et al., 2013; Gustavsen, 2017; Miles & Stipek, 2006; Yang et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2018) in similar studies still the data were subject to social desirability bias. Teachers may wish for their interventions to be successful, and therefore, they may have a tendency to give high scores when assessing their children. In fact, we attempted to address this potential bias with the control group. Because the teachers in the control group were aware that they belonged to a different group and were implementing a new program, they, too, might have felt the desire to avoid looking unfavorable and raise their students’ scores. Future research can determine the program’s effects more effectively if they use multiple raters.

Also our sample size decreased due to above mentioned reasons. Future studies can target larger and diverse samples. Future studies can also investigate longitudinal impact of this program and impact of the program on academic achievement of children.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from following link: https://harranedutr-my.sharepoint.com/personal/hkotaman_harran_edu_tr/_layouts/15/onedrive.aspx?id=%2Fpersonal%2Fhkotaman%5Fharran%5Fedu%5Ftr%2FDocuments%2FDanceData&view=0.

References

Ashdown, M. D., & Bernard, E. M. (2012). Can explicit instruction in social and emotional learning skills benefit the social-emotional development, well-being, and academic achievement of young children? Early Childhood Education Journal, 39, 397–405. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-011-0481-x.

Balcı, A., Kotaman, H., & Aslan, M. (2021). Impact of earning on young children’s sharing behaviour. Early Child Development and Care, 191(11), 1757–1764. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2019.1674294.

Biber, K. (2016). The effects of folk dance training on 5–6 years children’s physical and social development. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 4(11), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v4i11.1820.

Borowski, G. T. (2021). How dance promotes the development of social and emotional competence. Arts Education Policy Review. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2021.1961109.

Capara, V. G., Barbaranelli, C., Pastorelli, C., Bandura, A., & Zimbardo, G. P. (2000). Prosocial foundations of children’s academic achievement. American Psychological Society, 11(4), 302–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00260.

Cassidy, J., & Asher, S. R. (1992). Loneliness and peer relations in young children. Child Development, 63(2), 350–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01632.x.

Chen, X., Yang, F., & Wang, L. (2013). Relations between shyness-sensitivity and internalizing problems in Chinese children: Moderating effects of academic achievement. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 825–836. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9708-6.

Fink, B., Blasin, B., Ravignani, A., & Shackelford, K. T. (2021). Evolution and functions of human dance. Evolution and Human Behavior, 42, 351–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2021.01.003.

Gou, Q., Zhou, J., & Feng, L. (2018). Pro-social behavior is predictive of academic success via peer acceptance: A study of Chinese primary school children. Learning and Individual Differences, 65, 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.05.010.

Gustavsen, A. M. (2017). Longitudinal relationship between social skills and academic achievement in a gender perspective. Cogent Education, 4, 1411035. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1411035.

Isaac, S., & Michael, W. (1995). Handbook in research and evaluation: a collection of principles, methods, and strategies useful in the planning, design, and evaluation of studies in education and the behavioral sciences Edits Publisher.

Kernberg, O. F. (1991). Aggression and love in the relationship of the couple. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 39(1), 45–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/000306519103900103.

Kirschner, S., & Tomasello, M. (2010). Joint music making promotes prosocial behavior in 4-year-old children. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31(5), 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.04.004.

Lobo, B. Y., & Winsler, A. (2006). The effects of a creative dance and movement program on the social competence of Head Start preschoolers. Social Development, 15(3), 502–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2006.00353.x.

Lorenz, K. (2021). On aggression. Routledge.

Marett, R. R. (2020). Antropology and classics Gece Kitaplığı.

Mead, M. (2015). Being teenager in Samoa. Alfa Yayınları.

Miles, B. S., & Stipek, D. (2006). Contemporaneous and longitudinal associations between social behavior and literacy achievement in a sample of low-income elementary school children. Child Development, 77(1), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00859.x.

Misch, A., Over, H., & Carpenter, M. (2016). I won’t tell: Young children show loyalty to their group by keeping group secrets. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 142, 96–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2015.09.016.

Panagiotopoulou, E. (2018). Dance therapy and the public school: The development of social and emotional skills of high school students in Greece. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 59, 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.11.003.

Paulus, M., & Moore, C. (2017). Preschoolers’ generosity increases with understanding of the affective benefits of sharing. Developmental Science, 20, https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12417.

Pereira, S. N., & Marques-Pinto, A. (2018). Development of a social and emotional learning program using educational dance: A participatory approach aimed at middle school students. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 59, 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2018.03.003.

Rabinowitch, T.-C., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2017). Synchronized movement experience enhances peer cooperation in preschool children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 160, 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2017.03.001.

Rajan, R. S., & Aker, M. (2020). The impact of an in-school dance program on at-risk preschoolers’ social-emotional development. Journal of Dance Education, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2020.1766689.

Sevdalis, V., & Keller, E. P. (2011). Captured by motion: Dance, action understanding, and social cognition. Brain and Cognition, 77, 231–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2011.08.005.

Seven, S. (2010). Adaptation of teacher assessment of social behavior scale to Turkish culture). Selçuk University Social Sciences Institute Journal, 23, 193–200.

Sunar, D., & Fidancı, E. P. (2016). Farklı türdeki özgecil davranışların erken gelişimi: Paylaşma, yardım etme ve bağış yapma. Türk Psikoloji Dergisi, 31(78), 26–41.

Teo, A., Carlson, E., Mathieu, J. P., Egeland, B., & Sroufe, L. A. (1996). A prospective longitudinal study of psychosocial predictors of achievement. Journal of School Psychology, 34(3), 285–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4405(96)00016-7.

Tomasello, M. (2015). Why we cooperate? Alfa Science.

Tomasello, M. (2020). A naturalhistory of humanmorality. Koç University.

Waal De, F. (2016). Bonobo and ateist: in search of humanism among the primates Metis Publications.

Wu, Z., Hu, Y. B., Fan, X., Zhang, X., & Zhang, J. (2018). The associations between social skills and teacher-child relationships: A longitudinal study among Chinese preschool children. Children and Youth Services Review, 88, 582–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.03.052.

Yang, F., Chen, X., & Wang, L. (2014). Relations between aggression and adjustment in Chinese children: Moderating effects of academic achievement. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 43(4), 656–669. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2013.782816.

Yang, F., Chen, X., & Wang, L. (2015). Shyness-sensitivity and social, school, and psychological adjustment in urban Chinese children: A four-wave longitudinal study. Child Development, 86(6), 1848–1864. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12414.

Zachopoulou, E., Tsapakidou, A., & Derri, V. (2004). The effects of developmentally appropriate music and movement program on motor performance. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 19, 631–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2004.10.005.

Acknowledgements

The authors have nothing to acknowledge.

Funding

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK). No funding was received for the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H. K: Conceived and designed the analysis. Planned Data Collection Process. Performed the analysis. Wrote the article. Contribute to Dancing Program Development Process S. Ö. İ: Manage Data Collection Procedure. Contribute to Dancing Program Development Process. Contribute to Writing Process. Ş. K: Developed Dancing Program, Manage Data Collection Procedure.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed consent

Parents of participants sign following consent letter.

This study is conducted by Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Kotaman. The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between dance activities in early childhood and children’s early academic and social skills. If you accept your child to participate in this study, your child will be asked to participate dance activities in his or her classroom twice a week for a total of 8 weeks. Each activity will take approximately 20 minutes to complete. Participation in the study is entirely voluntary, and no personally identifiable information will be requested from you. Your responses will be kept confidential and will only be evaluated by the researchers, and the information obtained will be used in scientific publications.

The study does not contain any elements that would cause personal discomfort. However, if you feel uncomfortable during the study due to questions or for any other reason, you are free to withdraw from the study. At the end of the study, any questions you have regarding this study will be answered. Thank you in advance for participating in this study.

Teachers sign following consent letter

This study is conducted by Prof. Dr. Hüseyin Kotaman. The purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between dance activities in early childhood and children’s early academic and social skills. If you participate in this study, you will be asked to implement pre-prepared dance activities in your classroom twice a week for a total of 8 weeks. Each activity will take approximately 20 minutes to complete. Participation in the study is entirely voluntary, and no personally identifiable information will be requested from you. Your responses will be kept confidential and will only be evaluated by the researchers, and the information obtained will be used in scientific publications.The study does not contain any elements that would cause personal discomfort. However, if you feel uncomfortable during the study due to questions or for any other reason, you are free to withdraw from the study. At the end of the study, any questions you have regarding this study will be answered. Thank you in advance for participating in this study.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest is present in the conduction or the reporting of this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kotaman, H., İnceoğlu, S. & Kotaman, Ş. Dancing program and young children’s social development. Curr Psychol 43, 19171–19179 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05730-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05730-1