Abstract

The current study explores a psychological mechanism and boundary conditions on the relationship between job autonomy and helping behavior. Using the conservation of resources theory, we investigated whether job autonomy is related to helping behavior through mindfulness. Moreover, we tested the moderating role of transformational leadership on the direct effect of job autonomy on mindfulness and the indirect effect of job autonomy on helping behavior via mindfulness. We used two time-lagged data sets across two studies (N = 252 employees in Study 1 and N = 182 employees in Study 2) conducted in Taiwan. Study 1 supported the proposed hypotheses, and the results were replicated in Study 2, which found that job autonomy was positively related indirectly to helping behavior through mindfulness. In addition, the results of Study 2 provided additional support for transformational leadership as a moderator on the direct and indirect effects of job autonomy on mindfulness and helping behavior. Specifically, the direct effect of job autonomy on mindfulness and the indirect effect of job autonomy on helping behavior via mindfulness were stronger when transformational leadership was high compared to low.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Helping behavior, and how to support it, is a critical topic in applied psychology and management that stems from the broader research on employee discretionary behavior (Lin et al., 2019; Zhu & Akhtar, 2014). In general, helping behavior refers to a type of extra-role behavior where employees voluntarily assist coworkers to prevent or solve coworkers’ work-related problems (Lin et al., 2019). Helping behavior is beneficial to a dynamic workforce in organizations as employees are working together interdependently and need combined effort to improve overall job performance (McAllister et al., 2007). Research has suggested that helping coworkers in the workplace can increase organizational effectiveness (Lin et al., 2019). For example, employees voluntarily assist (e.g., via constructive suggestions and valuable feedback) their coworkers or new members in job-related tasks so that those employees can acquire the necessary knowledge and skills to increase individual job performance, team performance, and organizational performance (De Clercq et al., 2019; Lin et al., 2019). Moreover, employees who engage in helping behaviors report high career advancement and reward recommendations, which in turn enhance their job self-efficacy, improve their reputation, and enable them to get opportunities for career development and success (Lin et al., 2019; McAllister et al., 2007).

Given the positive influences of helping behavior on employee, team, and organizational outcomes, a growing body of research has sought to understand what factors may lead to helping behavior (Euwema et al., 2007). Thus far, research has identified significant antecedents of helping behavior, such as individual factors (prosocial motivation; Lin et al., 2019); team factors (transformational leadership, coworker support and trust; Halbesleben & Wheeler, 2015; Zhu & Akhtar, 2014); organizational factors (societal culture; Euwema et al., 2007). Even though those studies have addressed what personal and organizational factors can influence employees’ helping behavior, less attention has been paid to investigating how specific job characteristics may relate to helping behavior (Piccolo & Colquitt, 2006). In the applied psychological and management fields, job characteristics (e.g., Hackman & Oldham, 1975) can shape employees’ task-oriented behaviors by increasing their motivation and job meaningfulness (Piccolo & Colquitt, 2006). However, this finding is inadequate to explain the linkage between job characteristics and employee extra-role behaviors, such as helping behaviors. Thus, there is a need to clarify and extend our knowledge to identify what specific job characteristics can increase employees’ inner resources related to employee helping behavior. Additionally, research has shown that designing employees’ jobs to enhance their motivation and encourage proactive actions requires leader support and involvement (Den Hartog & Belschak, 2012; Piccolo & Colquitt, 2006), suggesting that leadership is important to consider as well. However, there is relatively limited knowledge regarding what leader behaviors may serve as a boundary condition that can maximize the relationship between the job characteristic and employee helping behavior.

Accordingly, our research aims to contribute to the helping behavior literature in several ways. First, we examine the effect of job autonomy—as an important job characteristic referring to how much discretion, independence, and freedom employees have in performing work tasks (Hackman & Oldham, 1975)—on employee helping behavior. Especially compared to other job characteristics such as skill variety, task identity, and feedback (Hackman & Oldham, 1975), job autonomy has been shown to increase employees’ mental space and energy resources, which in turn can influence employee discretionary behaviors (Kao et al., 2022). Thus, examining the role of job autonomy on helping behavior enables us to uncover whether employees may be more motivated to perform such helping behavior when they see themselves as having more resources such as flexibility and freedom to make their own decisions and display voluntary behaviors.

Moreover, given that the current study investigates the relationship between job autonomy and helping behavior, we further examine a psychological mechanism underlying this relationship. Specifically, job autonomy represents the perceptions of freedom, independence, and discretion (i.e., the autonomous resources) that influence employees’ psychological state and motivation (Kao et al., 2022), which, in turn, facilitate the development of awareness and concentration (Brown & Ryan, 2003). In line with the conservation of resources theory (COR; Hobfoll, 1989), a flexible job with high levels of autonomy can support employee awareness, attention, and felt responsibilities to maintain and discover their inner resources and increase willingness to invest in resources, which in turn may impact subsequent extra-role behaviors (Kao et al., 2022; Lawrie et al., 2018). Therefore, we propose that mindfulness—a psychological state that involves nonjudgmental present-moment awareness and attention without rumination about the past or concern about the future (Hülsheger et al., 2013)—may play a mediating role in the relationship between job autonomy and helping behavior.

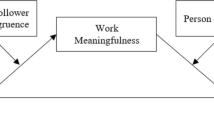

Finally, we examine whether transformational leadership serves as a boundary condition for the direct and indirect effects of job autonomy on mindfulness and helping behavior (via mindfulness). In an organization, leader behaviors play a significant role in influencing employees’ perceptions and behaviors (Hoch et al., 2018). In particular, transformational leadership — referring to a key behavior in which leaders engage to inspire subordinates with an optimistic vision of the future (Avolio & Bass, 1991) — supports employee autonomy (e.g., giving employees some choice of tasks, encouraging initiative, and informational feedback) as a contextual resource that likely enables employees to be mindful in order to reduce resource loss, increase awareness of inner resources, and acquire job resource, and thus might benefit employees’ personal resource reservoir (Hildenbrand et al., 2018). Therefore, transformational leadership may serve as a moderator of the relationships between job autonomy, mindfulness, and helping behavior. A moderated mediation model depicting our proposed relationships is presented in Fig. 1.

Conservation of resources theory

The conservation of resources (COR) theory, proposed by Hobfoll (1989), indicates that individuals are motivated to conserve and protect their resources and acquire new resources, which could be object resources (e.g., fixed assets), personal resources (e.g., personal traits and skills), condition resources (e.g., employment, tenure, seniority), and energy resources (e.g., credit, knowledge) (Hobfoll, 1989). Resource loss and resource gain are two key tenets of COR theory: The resource loss principle argues that losing resources is more salient than gaining resources (Hobfoll, 1989), and the resource gain principle contends that people aim to protect themselves against the loss of resources, recover from losses, and gain resources through the investment of resources (i.e., a resource gain spiral) (Hobfoll, 1989). In the applied psychology and management fields, resource loss serves as a useful perspective to understand how individuals respond to work stress (Alarcon, 2011). For example, employees with perceived work overload experience a loss of resources, and prolonged exposure results in high levels of strain (e.g., emotional exhaustion), including reduced personal accomplishment (Alarcon, 2011). However, the resource gain element explains how job resources can support employees’ positive work-related outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction) by increasing individuals’ inner resources at work. For example, job autonomy can be considered a potential job resource that allows employees to gain increased psychological resources and display high liveliness and energy (especially for employees who receive strong mentoring support, which is viewed as a contextual resource), thus ensuring enhanced job satisfaction (Bono et al., 2007).

According to the COR theory, positive job characteristics (e.g., autonomy-based characteristics) should facilitate individuals’ psychological states (Kao et al., 2022), which in turn could support entrance into a resource gain spiral and consequently positive behavioral outcomes (e.g., organizational citizenship behavior; OCB; Kim & Beehr, 2018). For instance, Kao et al. (2022) found that job characteristics, such as job autonomy (as a job resource that affords an employee a certain level of freedom), help satisfy the psychological need for autonomy and facilitate work engagement (a resource investment), which enhances employee voice behaviors. Similarly, during the psychological process underlying the link between job autonomy and employees’ behavioral outcomes, mindfulness, as a personal inner resource, enables employees to be aware and reserve essential psychological resources (Kroon et al., 2015). Specifically, mindful employees are more likely to be sensitive to their internal resource conditions and cultivate positive emotions, which avoid resource depletion, lead to effective resource development, and allow to obtain alternative resources because mindfulness focuses on the present moment and minimizes impulsive and habitual reactions to external and internal stimuli (Hafenbrack et al., 2020; Kroon et al., 2015). As such, mindful employees, with adequate psychological resources, are more willing to invest their remaining resources in demonstrating discretionary behaviors (Eldor & Harpaz, 2016). In addition, research suggests that individuals rely on contextual resources (e.g., leadership) to create conditions that can maximize their resource availability at work to stay in positive psychological states (Hildenbrand et al., 2018). Hence, employees with accumulated personal resources from multiple resources are more likely to engage in employee discretionary behavior, especially extra-role behavior that benefits others (Eldor & Harpaz, 2016). Accordingly, we apply the COR theory as a theoretical framework to better understand how job autonomy (i.e., a job resource) relates to mindfulness (i.e., a personal resource), which in turn may be positively related to helping behavior. Furthermore, we examine transformational leadership as a contextual resource that supports these relationships.

Job autonomy and mindfulness

Mindfulness refers to a psychological state of consciousness characterized by receptive attention to and awareness of present events and experiences, without evaluation, judgment, and cognitive filters (Hülsheger et al., 2013). In particular, research has noted that the level of employees’ present-moment attention is influenced by job-related factors (e.g., job demands) (Lawrie et al., 2018). For example, high job demands (e.g., work overload, role conflicts, and limited flexibility) may interfere with employees’ present-moment orientation, job involvement, and concentration due to increased psychological costs (Lawrie et al., 2018). In contrast, supportive and flexible tasks (e.g., job control) enable employees to be mindful, reflecting high personal resource reservoirs (Lawrie et al., 2018). In particular, from the perspective of COR theory, when employees are exposed to flexible working conditions, such as job autonomy, referring to the degree to which the job provides freedom and discretion to schedule work, has been regarded as a critical job resource investment (Halliday et al., 2018), which can decrease resource depletion and concentrating on the present-moment to perform their job-related tasks mindfully (Lawrie et al., 2018). Previous research has found that job-related factors, such as job autonomy and supervisor support, can enhance individuals’ awareness at work (Reb et al., 2015). Therefore, in line with the COR theory, we propose that job autonomy, as a pivotal job resource, could invest employees’ personal resources reflecting increased mindfulness. Accordingly, we hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 1: Job autonomy will be positively associated with mindfulness.

The relationships between job autonomy, mindfulness, and helping behavior

Helping behavior refers to employees’ voluntary actions that focus on the interpersonal and affiliative aspects of helping and supporting at work to maintain a cooperative work environment (McAllister et al., 2007). In particular, helping behavior is prosocial and other-oriented; it involves proactively providing support to promote and inspire others to get things done and solve or avoid work-related problems (McAllister et al., 2007). In line with COR theory, research has noted that the level of psychological resources is related to employee proactive behavior, suggesting that helping behavior is a resource investment behavior (Halbesleben & Wheeler, 2015), which can vary in psychological or personal resources, resulting in different behaviors. Indeed, abundant psychological resources give employees the motivational fuel to display helping behavior (De Clercq et al., 2019). According to this perspective, psychological resources are positively linked with helping behavior (De Clercq et al., 2019). For instance, Liu et al. (2020) reported that individuals with intrinsic resources put effort into helping other people with their problems instead of pursuing their own self-interest.

Mindfulness plays a key role in facilitating the awareness of psychological resources and promoting personal resources (Kroon et al., 2015), which can enhance employees’ positive work-related outcomes (e.g., pro-organizational behavior; Hafenbrack et al., 2020). Previous research revealed that highly mindful employees are more likely to identify their internal resource conditions (e.g., positive sensations, thoughts, and emotions) due to their open awareness towards present experiences, as opposed to dwelling on the past or future (Kroon et al., 2015). Thus, these employees can have positive emotions and attitudes which allow them to facilitate resource development (e.g., positive thoughts and social support networks). Kroon et al. (2015) also suggested that mindfulness can be regarded as a type of personal resource as it can help individuals accumulate their current resource levels and expand their alternative resource awareness. Therefore, these individuals tend to focus on the present moment, making them less susceptible to negative events or feelings associated with the loss of resources and more likely to obtain alternative resources (Hafenbrack et al., 2020; Kroon et al., 2015). According to the COR theory, employees with more available resources are more likely to invest resources by engaging in extra-role behavior (Eldor & Harpaz, 2016). In the same vein, mindful employees may be more willing to invest resources in demonstrating discretionary behaviors, such as helping behavior. In line with the COR theory, we propose that mindfulness, as a pivotal personal resource, supports employees’ willingness to display helping behaviors. Thus, we propose:

-

Hypothesis 2: Mindfulness will be positively associated with helping behavior.

According to the COR theory, job autonomy is a critical job resource (Halliday et al., 2018), providing employees with the mental space and energy resources to concentrate on ongoing events or current contexts (i.e., attentional awareness) and enhancing the awareness and development of personal psychological resources (such as mindfulness; Kroon et al., 2015). Recent research found that mindful employees can raise their awareness of inner resources and become more willing, efficient, and effective at investing resources to display discretionary behaviors such as helping behavior (De Clercq et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020). Therefore, based on the COR perspective, job autonomy likely serves as a job resource that is related to increased personal resources that can enhance employee mindfulness, ultimately, support a higher propensity to engage in subsequent helping behavior. Thus, we hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 3: Job autonomy will be indirectly related to helping behavior through mindfulness.

The moderating role of transformational leadership

In the workplace, due to supervisors’ authority over the reward system in the organization, employee behavior is influenced by supervisor behavior (Hoch et al., 2018). In particular, supervisors, as representatives of the organization, often keep in close contact and communication with employees so that their behaviors can significantly shape followers’ outcomes, such as psychological well-being (e.g., avoiding burnout), attitudes (e.g., job satisfaction and affective commitment), and behaviors (e.g., helping behavior) (Bono et al., 2007; Den Hartog & Belschak, 2012). Therefore, leadership has been viewed as an important contextual factor in increasing employees’ psychological resources (Arnold et al., 2015; Hildenbrand et al., 2018).

Research has indicated that transformational leaders are effective in influencing employees’ work motivation and behaviors in the workplace by increasing their self-confidence, hope, optimism, and resiliency, which are also resources included within the COR theory (Hildenbrand et al., 2018; Hobfoll, 1989). Thus, from a COR perspective, transformational leaders are viewed as a resource gain for employees through stimulating employees’ efforts to develop solutions to existing problems and supporting them by using their skills (Arnold et al., 2015). Therefore, transformational leaders can build a workplace that fosters followers’ psychological resources (e.g., self-confidence) and enable employees to display spontaneous emotion without fear of resource loss (Arnold et al., 2015). Transformational leaders also encourage their followers to trust each other, think about what they need, and how to pursue their goals (Kovjanic et al., 2013), thus promoting potential resource gain spirals (Hobfoll, 1989) and enhancing employees’ beliefs that they have the hope, optimism, and capability to achieve positive outcomes and foster supportive and affectionate bonds in the workplace. Furthermore, transformational leaders empower employees psychologically, encouraging them to think in new ways (Kovjanic et al., 2013). This empowerment provides employees with valuable resources (e.g., decision-making latitude) to help them overcome obstacles on their own in the workplace and develop their strengths.

Accordingly, we conceptualize transformational leadership as a contextual resource that should extend the pool of available resources to employees, especially employees’ mental and personal resources (Hildenbrand et al., 2018). This contextual resource investment should, in turn, increase the positive effects of job autonomy on employee mindfulness. In other words, employees working under transformational leaders are more likely to have higher levels of psychological resources (e.g., psychological capital) (Hildenbrand et al., 2018; Hobfoll, 1989). As such, the interaction between increased job resources (i.e., job autonomy) and increased contextual resources (i.e., transformational leadership) may be associated with maximum levels of personal psychological resources that support higher mindfulness. Therefore, in line with COR theory, we aim to examine whether the association of job autonomy with mindfulness will be stronger when transformational leadership is high compared to when it is low. Thus, we propose:

-

Hypothesis 4: Transformational leadership will moderate the effect of job autonomy on mindfulness. Specifically, the relationship will be stronger when transformational leadership is high compared to when transformational leadership is low.

Under transformational leaders, employees are more likely to (a) receive support in using their skills to develop solutions for existing problems, (b) perceive trust and encourage to think about what they need and how they achieve their goals, and (c) receive empowerment to think in new ways rather than follow the existing rules. Particularly, transformational leadership can be regarded as a contextual resource that enhances the pool of resources available to employees, particularly their mental and personal resources (Hildenbrand et al., 2018). Hence, employees who work with high levels of autonomy and under a transformational leader are likely to have highest support for mindfulness (i.e., highest personal resources), which may positively impact their subsequent extra-role behaviors (Den Hartog & Belschak, 2012; Svendsen et al., 2018). According to COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989), when it comes to allocating resources to the process that suggests a connection between resources available and employee behavior, those with more resources are in a better position to do so. Therefore, we expect that transformational leadership may influence the relationship between job autonomy and helping behavior (through mindfulness). Accordingly, we propose:

-

Hypothesis 5: Transformational leadership will moderate the indirect effect of job autonomy on helping behavior via mindfulness. Specifically, the indirect effect of job autonomy on helping behavior via mindfulness will be stronger when transformational leadership is high compared to when it is low.

Overview of studies

For this research, we conducted two studies to examine a psychological mechanism (i.e., mindfulness) underlying the relationship between job autonomy and helping behavior and the boundary conditions on the effects of job autonomy on mindfulness and helping behavior. In Study 1, we collected two-wave data from N = 252 full-time employees in Taiwan, to test whether job autonomy is positively related to mindfulness (Hypothesis 1), whether mindfulness is associated with helping behavior (Hypothesis 2), and whether the relationship between job autonomy and helping behavior is mediated by mindfulness (Hypothesis 3). In Study 2, we replicated the measures and procedure in Study 1 and additionally measured transformational leadership from N = 182 full-time employees in Taiwan. Study 2 examined the full theoretical model depicted in Fig. 1 by investigating the moderating role of transformational leadership in the direct effect of job autonomy on mindfulness (Hypothesis 4) and the indirect effect of job autonomy on helping behavior via mindfulness (Hypothesis 5). These two studies together provide a firm research foundation on which to investigate our hypotheses.

Study 1 method

Participants and procedure

In Study 1, data were collected via online surveys at two different time points to decrease common method variance (CMV; Podsakoff et al., 2012). The second survey (Time 2) was conducted 4 weeks after the first survey (Time 1). Executive MBA students were recruited at a university in Northern Taiwan using a snowball sampling technique. Potential participants were invited via email to participate in the online survey and share the link with others who might be interested. Only those completing the first-round survey were invited to participate in the second-round survey. To increase the quantity and quality of data collection at two-time points, we followed four practices proposed by previous research to facilitate the meticulous design and execution of the procedure, thereby ensuring a high level of conscientious response (e.g., Huang et al., 2015; Meade & Craig, 2012). First, the cover letter of the questionnaires explicitly delineated that the study exclusively targeted full-time employees (i.e., at least 40 working hours per week). It articulated the purpose of the study, detailed the research procedure, and outlined confidentiality precautions. Particularly, the participants were informed about the response time required to complete the survey (e.g., it would take approximately 4–5 min to complete the survey). The participants were allowed to stop completing the questionnaires if they felt uncomfortable.

Second, in the cover letter, participants were informed that their responses would only be used for research purposes and would be identified by their email address to enable matching across the two waves. Third, to encourage participants’ effort of responding, each participant who completed the survey at both Time 1 and Time 2 was compensated with an e-gift card valued at approximately 3.00 USD.

Lastly, we adopted the approach recommended by Huang et al. (2012) to identify insufficient effort responders, excluding those who allocated less than 2 seconds per item post data collection or exhibited careless response patterns (e.g., consistently selecting “strongly disagree” for all items). To enhance the response rate, two additional reminder emails were sent to the participants preceding the survey's closure.

At Time 1, a total of 318 full-time employees completed the survey. To ensure confidentiality, we provided an individual number for each participant to match the questionnaires of two waves. At Time 2, 252 of the 318 employees (retention rate = 79.25%) completed the survey. In the end, 252 employees completed both surveys. In the first wave, we collected information on job autonomy and demographic variables (e.g., gender and tenure). In the second wave, we collected information on mindfulness and helping behaviors. Most participants were 30–39 years of age (44.00%) and reported an educational level of a bachelor’s degree (55.60%), followed by a master’s degree (38.90%). The average organization tenure was 7.70 years (SD = 12.68).

Measures

All measures were initially translated from English to Chinese. To ensure that all translated items were consistent with their original meaning, we applied a back-translation procedure to the translated versions (Brislin, 1980). The following items were rated by using a 5-point Likert-type response scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Job autonomy

Job autonomy was measured using a 3-item scale developed by Spreitzer (1995). Example items included “I have significant autonomy in determining how I do my job” and “I can decide on my own how to go about doing my work.” The Cronbach’s alpha for job autonomy was 0.90.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness was assessed using a 4-item scale developed by Brown and Ryan (2003). Example items included “I can stay focused on what’s happening in the present” and “I rush through activities without being really attentive to them.” The Cronbach’s alpha for mindfulness was 0.75.

Helping behavior

We measured helping behavior with five items adapted from Williams and Anderson (1991). An example item was “I help others who have been absent.” The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.76.

Control variables

Previous research suggested that gender and tenure are related to helping behavior (i.e., Peng & Zeng, 2017). Therefore, gender and tenure were included as control variables in the current study.

Analytic strategy

Prior to hypothesis testing, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to assess the discriminant validity of our key constructs and evaluate the presence and influence of CMV using the procedure by Williams et al. (2010). We examined the main effects (Hypotheses 1 and 2) and indirect effect (Hypothesis 3) by using regression-based path analyses with the M-plus code developed by Stride et al. (2015) to test the hypothesized model. Moreover, the bootstrapping approach (N = 10,000), a statistical resampling method that estimates the standard deviation of a model from a sample (Hayes, 2015), was used to calculate a bias-corrected 95% confidence interval (BCCI) for the indirect effect of job autonomy on helping behavior through mindfulness (Hypothesis 3).

Power analyses

We conducted power analyses to determine whether the sample size in Study 1 was adequate. Specifically, we used the web-based interface power4SEM (Jak et al., 2021) to examine statistical power by conducting root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) (MacCallum et al., 1996). We evaluated the power to reject close fit (H0: RMSEA ≤ 0.05) when the population is not-close fit (H1: RMSEA = 0.08). The power to reject RMSEA of 0.05 was equal to 0.88, indicating that with an intended sample size of 252, degrees of freedom of 51, and an alpha level of 0.05 were achieved. Given that the sample size of this study was confirmed to be adequately powered (i.e., a power of over 0.80) to reject the close fit model, we have the confidence to conduct the following analyses.

Study 1 results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, correlations, and reliability statistics of the variables included in both studies. Job autonomy was significantly positively correlated with mindfulness (r = 0.22, p < 0.001). Mindfulness was significantly positively correlated with helping behavior (r = 0.42, p < 0.001).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

We conducted a CFA to examine the discriminant validity of the variables of the measurement model using M-plus 8.6. The CFA results showed that a three-factor model provided a better fit than other models (χ2 (51) = 68.37, p = 0.05; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.04; SRMR = 0.04). Specifically, we compared the model fit of the three-factor model to a two-factor model that combined mindfulness and helping behavior into one factor. Results revealed that the three-factor model provided a better fit than the two-factor model (χ2 (53) = 195.05, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.87; TLI = 0.84; RMSEA = 0.10; SRMR = 0.08) or a single-factor model (all of the variables in one factor) (χ2 (54) = 618.37, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.48; TLI = 0.37; RMSEA = 0.20; SRMR = 0.19). Overall, the results showed that the three-factor model provided a better fit than other alternative models.

Next, we also applied the CFA marker technique (Williams et al., 2010) in M-plus 8.6 to assess whether CMV influenced our estimates, including initial, baseline, Method-C, Method-U, and Method-R models to test for the presence and magnitude of method effects, using a measure of perceptions of self-undermining as a marker variable, which is not theoretically related to the substantive variables in our model (Williams et al., 2010). As shown in Table 2, the comparison between the Baseline and Method-C models (Δχ2(1) = 0.31, n.s.) was not significant. Therefore, it can be ascertained that there was no common method bias in Study 1.

2SLS: post-checking the endogeneity of the model

Given that endogeneity might affect relationships in field research (i.e., non-experimental study designs) (Antonakis et al., 2010), we applied model implied instrument variable estimation using the Two-Stage Least Square (2SLS) approach by R package “AER” for the robustness check (Antonakis et al., 2010; Wooldridge, 2008). We followed the recommended criterion of appropriate instrumental variables that are related to the independent variable but are unrelated to the dependent variable (Semadeni et al., 2014). After evaluating several alternatives and confirming the coefficient of intercorrelation, we set three external instrument variables for post-checking endogeneity in our model: autocratic leadership, psychological safety, and perceived involvement, identified in previous research as factors influencing employees' job autonomy (Fürstenberg et al., 2021; Itzchakov et al., 2023; Pierro et al., 2009; Scrimpshire et al., 2022). These instrument variables were measured as follows: “My supervisor makes decisions alone without asking for suggestions (autocratic leadership).”; “In my work unit, I can freely express my thoughts (psychological safety).”; “Company policies and procedures are clearly communicated to employees (perceived involvement).” (de Hoogh et al., 2004; Liang et al., 2012; Riordan et al., 2005).

Table 3 shows the results of the specification tests for the 2SLS estimations. Specifically, the weak instrument test indicated that our instruments were suitable and valid (F (3, 246) = 40.51, p < 0.001; see Model 3). The Wu-Hausman test similarly revealed that endogeneity does not appear to be a concern (F (2, 245) = 0.28, p = 0.76; see Model 3). Moreover, we conducted the Sargan test for over-identification on structural paths to examine if instrument variables are correlated with an error, indicating that the correlated errors do not significantly bias the estimates in the model (χ2 (1) = 0.21, p = 0.65; see Model 3). Therefore, our 2SLS check indicates insignificant threats from endogeneity of model misspecification.

Hypotheses testing

The results of the path analyses are shown in Table 4. Hypothesis 1 proposed that job autonomy is positively related to mindfulness. As shown in Table 4, job autonomy was significantly positively related to mindfulness (B = 0.18, SE = 0.06, p = 0.004); thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported. Hypothesis 2 proposed that mindfulness is positively related to helping behavior. The results showed that mindfulness was significantly positively related to helping behavior (B = 0.45, SE = 0.11, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 3 proposed an indirect relationship between job autonomy and helping behavior through mindfulness. Given that both Hypotheses 1 and 2 were supported, we tested the indirect effect of job autonomy on helping behavior via mindfulness using a bootstrapping procedure (Hayes, 2015). The bootstrapping results showed a significant indirect effect of job autonomy on helping behavior (estimate = 0.08; SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [0.03, 0.17]); therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Study 2 method

Participants and procedure

In Study 2, two-wave data were again collected via online questionnaires from participants who were full-time employees in Taiwan. Consistent with the recruitment procedure conducted in Study 1, we ensured a meticulous approach to confirm the quantity and quality of two-wave data collection. In short, participants were assured of the confidentiality of the questionnaire, with explicit information that the collected data, results, and email addresses would be exclusively used for research purposes. Furthermore, the participants were informed of an estimated time (approximately 5–6 min) for survey completion. Moreover, to enhance the response rate, participants who completed the two-wave questionnaires were offered a 3 USD e-gift card as an incentive. Lastly, we excluded insufficient effort respondents who spent less than 2 seconds on each response or displayed insensitive response patterns (e.g., “strongly disagree” for all items).

At Time 1, the employees were asked to fill out the measures of job autonomy, transformational leadership, and demographic information. At Time 2 (1 month after Time 1), we requested the participants to measure mindfulness and helping behavior. At Time 1, a total of 313 employees completed the survey (response rate = 84.37%); at Time 2, 182 employees responded to the survey (retention rate = 58.15%). This sample size was also deemed to satisfy our post hoc RMSEA power-based calculation, which required a minimum sample of 148 participants to achieve 0.80 power to reject RMSEA at 0.05 (Jak et al., 2020). The final sample comprised workers from different industries, mainly communication and education (57.7%). Participants were 58.2% female and 41.8% male, most of the participants held a bachelor’s degree (54.4%). The average work tenure with the organization was 6.23 years (SD = 5.63).

Measures

Participants responded to all survey items using a 6-point Likert-type scale with anchors ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (6) unless otherwise noted. We used the same measures as Study 1 to assess job autonomy, mindfulness, and helping behavior. The Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.89, 0.83, and 0.84, respectively.

Transformational leadership (Time 1)

Transformational leadership was measured using a 9-item scale from Avolio and Bass (1991). Example items included “My supervisor talks about his/her most important values and beliefs,” “My supervisor spends time teaching and coaching,” and “My supervisor talks optimistically about the future.” The Cronbach’s alpha for transformational leadership was 0.93.

Analytic strategy

To test the hypothesized model, we used the latent moderated structural equations (LMS) approach by the Mplus macro (Muthén & Muthén, 2017), which allows us to increase a model’s power, reduce the likelihood of biased estimates, and estimate latent interaction effects (Cheung et al., 2021; Maslowsky et al., 2015). Following the LMS procedure, we first conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) by estimating a measurement model to assess the construct validity of the latent study variables and control variables, using the maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors (MLR). The second step is to estimate the baseline model that does not contain the interaction effect. Next, we added the latent interaction term using the XWITH command and compared them to our proposed baseline model via the log-likelihood difference test (Δ -2LL; Maslowsky et al., 2015). A significant change in the log-likelihood after the addition of the interaction effect indicates that the model containing the interaction term is preferable over the baseline model. Finally, we tested all hypotheses (Hypotheses 1, 2, and 4) and examined the mediation (Hypothesis 3) and conditional indirect effect of job autonomy on helping behavior (Hypothesis 5) by utilizing the Monte Carlo simulation approach (N = 5,000,000) (Preacher & Selig, 2012) within R console to find the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval of estimated parameters.

Power analyses

For evaluating the statistical power in Study 2, we applied the same approach in Study 1 that assumed a population RMSEA of 0.08, indicating poor model fit, and we tested the close fit (H0: RMSEA ≤ 0.05) with an intended sample size of 182, degrees of freedom of 84, and an alpha level of 0.05. The resulting power to reject close fit equals 0.89, representing satisfied statistical power. Thus, our results indicated that the present study was sufficiently powered.

Study 2 results

Descriptive statistics

Consistent with Study 1, Table 1 again shows that job autonomy (r = 0.20, p = 0.007) and transformational leadership (r = 0.15, p = 0.04) were positively correlated with mindfulness. Mindfulness was significantly positively correlated with helping behavior (r = 0.38, p < 0.001).

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

The CFA results showed that a four-factor model (χ2 (84) = 202.96, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.91; TLI = 0.89; RMSEA = 0.09; SRMR = 0.06) providing a better fit than the three-factor model that combined mindfulness and helping behavior into one factor (χ2 (87) = 395.11, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.77; TLI = 0.73; RMSEA = 0.14; SRMR = 0.11); a two-factor model that combined job autonomy and transformational leadership into one factor and combined mindfulness and helping behavior into one factor (χ2 (89) = 640.61, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.59; TLI = 0.52; RMSEA = 0.19; SRMR = 0.14); and a single-factor model (χ2 (90) = 1058.88, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.29; TLI = 0.17; RMSEA = 0.24; SRMR = 0.23). Overall, the results showed that the four-factor model provides the best fit to the data. In addition, following Williams et al.’s (2010) procedures, we used a measure of work-home segmentation preference as a marker variable, which is theoretically unrelated to the substantive variables in our model, to examine the extent to which CMV existed in our data. The results also showed that the chi-square difference (Δχ2(1) = 0.50, n.s.) between the Baseline model and Method-C model was not significant. Results indicated that CMV is not present in Study 2.

2SLS: post-checking the endogeneity of the model

To check if our results are biased due to endogeneity in Study 2, we also tested the validity of our instrument variables and conducted the 2SLS estimation (Antonakis et al., 2010; Wooldridge, 2008), which is the same method in Study 1. In line with the nature of instrumental variables, we replicated the same procedure in Study 1 and selected social norms and organizational culture as instrumental variables, which were measured as follows: “Most people in my workgroup think that respond e-mail and messages immediately is something ought to do (social norms)”; “my organization encourages me to embrace challenges (organizational culture)” (Wallach, 1983; White et al., 2009). The results of the weak instrument test indicated that these instruments are suitable for determining the scaling variable of job autonomy (F (4, 175) = 5.46, p < 0.001). The results of the Wu-Hausman test (F (3, 173) = 2.46, p = 0.06; F (2, 175) = 2.24, p = 0.11) supported that endogeneity is not a concern in our model. Finally, the results of the Sargan test indicated non-significance (χ2 (1) = 0.004, p = 0.95; χ2 (2) = 0.58, p = 0.75), suggesting that these instruments are not biased. Thus, these results supported that no endogeneity bias existed in our model estimates. The results for the 2SLS were reported in model 1 and model 2 in Table 3.

Replication of Study 1 findings regarding hypotheses 1, 2, and 3

While using the LMS method to estimate the hypothesized model, we followed Cheung et al. (2021) procedure to first estimate a measurement model and a baseline model without latent interactions. The results showed that this measurement model had adequate fit to the data (χ2 [106] = 204.426, p < 0.001; CFI = 91, TLI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.06), and the factor loadings of the indicators in each of the four constructs were all significant (p < 0.001). Then, the results suggest that the proposed baseline model without the interaction effects also had an adequate fit (χ2 [107] = 203.699, p < 0.001; CFI = 91, TLI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.06). Next, we estimated the model containing the interaction term of job autonomy and transformational leadership. Comparing the log-likelihood values between the baseline model and structural model gave TRd (df = 1) = 6.88 (p = 0.009), indicating that adding the latent interaction effect made a statistically significant improvement to model fit, and thus allowing us to estimate the structural model with latent interactions for hypothesis testing.

Figure 2 depicts the LMS results of our hypothesized model. As shown in Fig. 2, job autonomy was positively related to mindfulness (B = 0.16, SE = 0.05, p = 0.002); thus, Hypothesis 1 was supported. The results showed that mindfulness was positively related to helping behavior (B = 0.52, SE = 0.12, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2.

Given that both Hypotheses 1 and 2 were supported, we tested the indirect effect of job autonomy on helping behavior via mindfulness using a Monte Carlo simulation approach (Preacher & Selig, 2012). The results also showed a significant indirect effect of job autonomy on helping behavior (estimate = 0.08, 95% BCCI = [0.03, 0.16]); therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Hypotheses testing: moderation and moderated mediation

Hypothesis 4 proposed that transformational leadership would moderate the relationship between job autonomy and mindfulness. The results in Fig. 2 showed that transformational leadership strengthens the positive effect of job autonomy on mindfulness (B = 0.12, SE = 0.05, p = 0.03). Moreover, we plotted the interaction figure (see Fig. 3) and the simple slope test (Aiken & West, 1991) suggested that the relationship between job autonomy and mindfulness was stronger when the level of transformational leadership was high (B = 0.25, SE = 0.08, p = 0.002) versus low (B = 0.07, SE = 0.06, p = 0.21), supporting Hypothesis 4.

Hypothesis 5 proposed that transformational leadership would moderate the indirect effect of job autonomy on helping behavior through mindfulness. Using Preacher and Selig’s (2012) Monte Carlo simulation approach in R console, the results indicated that the index of moderated mediation was significant (index MM = 0.06, 95% BCCI [0.01, 0.15]). The indirect effect of job autonomy on helping behavior was stronger when the level of transformational leadership was high (estimate = 0.13, 95% BCCI [0.05, 0.24]) versus low (estimate = 0.04, 95% BCCI [-0.02, 0.11]) (see Fig. 4). Therefore, Hypothesis 5 was supported.

General discussion

The current research conducted two studies to examine the relationships between job autonomy, mindfulness, and helping behavior and boundary conditions on these relationships. In Study 1, we found that job autonomy was positively related to mindfulness and indirectly positively related to helping behavior through mindfulness. In Study 2, we replicated the indirect relationship of job autonomy on helping behavior, through mindfulness, that we found in Study 1 and extended these findings to examine the supportive moderating role of transformational leadership on this process. Together, our findings indicated that, in line with COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989), when employees receive a high level of job autonomy as an important job resource, it enables them to own more personal resources, that is, mindfulness, which can facilitate awareness of inner resources and prevent resource depletion. Moreover, individuals with higher autonomy and mindfulness were more likely to report engaging in helping behavior. Our findings support the significance of job autonomy as a critical job resource that can support investing in personal resources (i.e., mindfulness) to display employee extra-role behavior (i.e., helping behavior). Additionally, we found that transformational leadership, a type of contextual resource, can expand employees’ pool of available psychological resources at work, acting as a significant moderator to strengthen the direct and indirect relationships of job autonomy, mindfulness, and helping behavior. These findings demonstrate that employees can receive job resources (i.e., job autonomy) and contextual resources (i.e., transformational leadership) to maximize their personal resources (i.e., mindfulness) which is associated with increased voluntary behaviors (i.e., helping behavior) for enhancing organizational effectiveness. The current research contributes to the existing helping behavior and leadership literature by extending the application of COR theory’s perspective on employee discretionary behavior and identifying the significance of multiple resources (e.g., job, personal, and contextual resources) in enhancing employees’ positive outcomes in the workplace. The findings from these two studies have meaningful impacts on theory, research, and practice; we describe these implications in detail next.

Theoretical implications

Our findings offer two notable contributions to the helping behavior and leadership literature. First, our results indicate that job autonomy is positively related to employee mindfulness, which influences helping behavior. Drawing on past findings on the job characteristics model (Hackman & Oldham, 1975) and COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989), job autonomy, as a significant job characteristic and critical job resource, can allow employees to increase their personal inner resources (mindfulness), further influencing employees’ helping behavior. This is in line with previous research that suggests that job-relevant factors (e.g., job autonomy) enhance employees’ awareness in the work setting and these highly aware employees are more willing to demonstrate positive workplace behavior (Reb et al., 2015). Our findings also correspond to the fact that job autonomy has been regarded as an essential external job resource from the perspective of resource investment (Halliday et al., 2018) for the fulfillment of employees’ personal resources. Job resources can facilitate the cultivation of personal resources, which is related to voluntary workplace behaviors (Liu et al., 2020). In a similar vein, De Clercq et al. (2019) found that employees who receive resources from the workplace tend to display discretionary behaviors. Moreover, recent research suggested that mindfulness can be viewed as a personal resource to reduce job stress (Kroon et al., 2015; Lawrie et al., 2018) and increase individuals’ general helping behavior (Hafenbrack et al., 2020). The present studies shed light on the resource gain spiral by indicating that job autonomy is a job resource that increases personal resource gain, and provides a conceptual model that addresses how and why job autonomy could facilitate employees’ helping behaviors via enhancing their mindfulness. This suggests that mindfulness (a type of personal resource) is a critical psychological mechanism for a deeper understanding of why job autonomy is associated with employees’ helping behaviors at work.

Second, our findings provide empirical evidence that transformational leadership significantly strengthens the direct relationship between job autonomy and mindfulness and the indirect relationship between job autonomy and helping behavior (through mindfulness). Drawing on COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989) and past research (e.g., Arnold et al., 2015), contextual resources in the workplace (e.g., support from the leader) influence the psychological resource pool accessible to employees and further lead to positive work-related outcomes. Particularly, previous research has highlighted transformational leadership as a significant contextual resource that can expand the range of resources accessible to employees (De Clercq & Belausteguigoitia, 2017; Hildenbrand et al., 2018) which can decrease employees’ resource depletion and increase their resource gains (Arnold et al., 2015; Lawrie et al., 2018). Svendsen et al. (2018) noted a similar finding that high transformational leadership and high job autonomy can motivate employees to engage in employee voice behaviors. Our findings extend previous research that employees who work with a transformational leader tend to execute their work mindfully and perceive less resource depletion and more resource gain, which in turn increases their levels of personal resources to display discretionary behaviors (i.e., helping behaviors) in the work setting. Additionally, prior research found that contextual resources (e.g., transformational leadership) can buffer the negative influence of job stress (e.g., perceived organizational politics) on employees’ OCBs, implying that employees are likely to engage in extra-role behaviors that contribute to organizational effectiveness when they gain access to contextual resources (De Clercq & Belausteguigoitia, 2017). The findings in the current studies further support this perspective that transformational leadership can be viewed as a contextual resource that strengthens the indirect relationship between job autonomy and extra-role behavior (e.g., helping behavior). Overall, our findings contribute to the development of existing knowledge in the applied psychology and management fields.

Practical implications

Our findings provide meaningful implications for practice regarding how to promote employee helping behavior effectively. Namely, organizational policies and practices (e.g., job design and mindfulness-based stress reduction) that increase resources such as job autonomy and mindfulness may have a positive impact on helping behaviors. First, employees can benefit from a highly autonomous job design supplied by the organization. Specifically, flexible work hours, autonomous decision-making, and unrestrained expression of opinions, instead of close monitoring and controlling oversight, may be effective ways to enable employees to experience increased mindfulness and increased intention to help other co-workers contribute to organizational effectiveness. Second, organizations can design or develop mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and meditation practices, which improve employees’ acceptance, reflection, and concentration, to increase employees’ awareness of resources and willingness to invest in resources, which in turn motivate employees to demonstrate helping behavior (Hafenbrack et al., 2020).

Finally, our results suggest that transformational leadership is a conditional factor that supports the positive relationships between job autonomy and mindfulness and helping behaviors; therefore, increasing transformational leader behavior may be a helpful tool for organizations to maximally support employees. Conversely, this also suggests that job autonomy or mindfulness interventions may be less effective if employees are embedded in contexts without transformational leaders. Organizations that value transformational leader development can select and train employees to be transformational leaders through human resource (HR) practices. These strategies may increase the policies and implementation effectiveness for increasing transformational leadership within the organization. For example, a set of personality assessments should be conducted to evaluate employees, and those with high extraversion and agreeableness should be considered for leadership positions, as people with these traits tend to be more willing to implement transformational leadership (Hildenbrand et al., 2018). Furthermore, HR practitioners can design training courses to improve supervisors’ behavior and skills, such as by changing leadership styles through role-playing or clearly defining what behavior is consistent with transformational leadership, which will aid in developing and exhibiting transformational leadership (Hildenbrand et al., 2018).

Limitations and future research

This study is not without limitations. First, we collected data using purposive sampling (Etikan et al., 2016). This approach can be prone to sampling bias, resulting in the collected data not accurately representing the wider population (Etikan et al., 2016). Second, although we collected the data at two time points, mindfulness (i.e., the mediator) and helping behavior (i.e., the criterion) were collected simultaneously, which cannot completely exclude the possibility of reverse causality. Thus, future research should conduct a longitudinal study design that collects data at three time points. Third, prior research notes that personality is related to OCBs (Ilies et al., 2009). Hence, it seems worthwhile for future research to consider employee personality traits as control variables in the theoretical model to further validate our findings. Finally, our results were obtained from a sample of employees in Taiwan, which is categorized as a culture high in collectivism. Hence, cultural differences (e.g., individualism vs. collectivism) may be related to differences in expressing oneself, influencing helping behavior (Euwema et al., 2007). Accordingly, these results may not be generalizable to Western cultures that emphasize individualism. Therefore, future research could collect data in other countries that emphasize individualism to examine cultural impacts.

Conclusion

Drawing on the conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll, 1989), our study contributes to the literature by identifying the relationships between job autonomy, mindfulness, and helping behavior and investigating the moderating roles of transformational leadership in these relationships. Our results shed light on the potential importance of mindfulness as a psychological mechanism underlying the relationship between job autonomy and helping behavior. Additional findings note that transformational leadership increases job autonomy’s direct and indirect effects on mindfulness and on helping behavior through mindfulness. These findings bring a new perspective and comprehensive understanding regarding the psychological process by which job autonomy is related to helping behavior and highlight the key role of transformational leadership in organizations’ efforts to maximize the positive effect of job autonomy on helping behavior.

References

Aiken, L. S. & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

Alarcon, G. M. (2011). A meta-analysis of burnout with job demands, resources, and attitudes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79(2), 549–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.03.007

Antonakis, J., Bendahan, S., Jacquart, P., & Lalive, R. (2010). On making causal claims: A review and recommendations. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(6), 1086–1120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.10.010

Arnold, K. A., Connelly, C. E., Walsh, M. M., & Martin Ginis, K. A. (2015). Leadership styles, emotion regulation, and burnout. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(4), 481–490. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039045

Avolio, B. J., & Bass, B. M. (1991). The full range leadership development programs: Basic and advanced manuals. Bass, Avolio & Associates.

Bono, J. E., Foldes, H. J., Vinson, G., & Muros, J. P. (2007). Workplace emotions: The role of supervision and leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1357–1367. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1357

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (pp. 389–444). Allyn and Bacon.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Cheung, G. W., Cooper-Thomas, H. D., Lau, R. S., & Wang, L. C. (2021). Testing moderation in business and psychological studies with latent moderated structural equations. Journal of Business and Psychology, 36(6), 1009–1033. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-020-09717-0

De Clercq, D., & Belausteguigoitia, I. (2017). Mitigating the negative effect of perceived organizational politics on organizational citizenship behavior: Moderating roles of contextual and personal resources. Journal of Management & Organization, 23(5), 689–708. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2017.7

De Clercq, D., Rahman, Z., & Haq, I. U. (2019). Explaining helping behavior in the workplace: The interactive effect of family-to-work conflict and Islamic work ethic. Journal of Business Ethics, 155(4), 1167–1177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3541-3

de Hoogh, A. H., Koopman, P. L., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2004). De ontwikkeling van de CLIO: een vragenlijst voor charismatisch leiderschap in organisaties. Gedrag & Organisatie, 17(5). https://doi.org/10.5117/2004.017.005.008

Den Hartog, D. N., & Belschak, F. D. (2012). When does transformational leadership enhance employee proactive behavior? The role of autonomy and role breadth self-efficacy. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024903

Eldor, L., & Harpaz, I. (2016). A process model of employee engagement: The learning climate and its relationship with extra-role performance behaviors. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(2), 213–235. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2037

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

Euwema, M. C., Wendt, H., & Van Emmerik, H. (2007). Leadership styles and group organizational citizenship behavior across cultures. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 28(8), 1035–1057. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.496

Fürstenberg, N., Alfes, K., & Kearney, E. (2021). How and when paradoxical leadership benefits work engagement: The role of goal clarity and work autonomy. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 94(3), 672–705. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12344

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076546

Hafenbrack, A. C., Cameron, L. D., Spreitzer, G. M., Zhang, C., Noval, L. J., & Shaffakat, S. (2020). Helping people by being in the present: Mindfulness increases prosocial behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 159, 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2019.08.005

Halbesleben, J. R., & Wheeler, A. R. (2015). To invest or not? The role of coworker support and trust in daily reciprocal gain spirals of helping behavior. Journal of Management, 41(6), 1628–1650. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312455246

Halliday, C. S., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., Ordóñez, Z., Rogelberg, S. G., & Zhang, H. (2018). Autonomy as a key resource for women in low gender egalitarian countries: A cross-cultural examination. Human Resource Management, 57(2), 601–615. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21874

Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2014.962683

Hildenbrand, K., Sacramento, C. A., & Binnewies, C. (2018). Transformational leadership and burnout: The role of thriving and followers’ openness to experience. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000051

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Hoch, J. E., Bommer, W. H., Dulebohn, J. H., & Wu, D. (2018). Do ethical, authentic, and servant leadership explain variance above and beyond transformational leadership? A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Management, 44(2), 501–529. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316665461

Huang, J. L., Bowling, N. A., Liu, M., & Li, Y. (2015). Detecting insufficient effort responding with an infrequency scale: Evaluating validity and participant reactions. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(2), 299–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-014-9357-6

Huang, J. L., Curran, P. G., Keeney, J., Poposki, E. M., & DeShon, R. P. (2012). Detecting and deterring insufficient effort responding to surveys. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27(1), 99–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-011-9231-8

Hülsheger, U. R., Alberts, H. J., Feinholdt, A., & Lang, J. W. (2013). Benefits of mindfulness at work: The role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2), 310–325. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031313

Ilies, R., Fulmer, I. S., Spitzmuller, M., & Johnson, M. D. (2009). Personality and citizenship behavior: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(4), 945–959. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013329

Itzchakov, G., Weinstein, N., Vinokur, E., & Yomtovian, A. (2023). Communicating for workplace connection: A longitudinal study of the outcomes of listening training on teachers’ autonomy, psychological safety, and relational climate. Psychology in the Schools, 60(4), 1279–1298. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22835

Jak, S., Jorgensen, T. D., Verdam, M. G., Oort, F. J., & Elffers, L. (2021). Analytical power calculations for structural equation modeling: A tutorial and Shiny app. Behavior Research Methods, 53, 1385–1406. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-020-01479-0

Kao, K. Y., Hsu, H. H., Thomas, C. L., Cheng, Y. C., Lin, M. T., & Li, H. F. (2022). Motivating employees to speak up: Linking job autonomy, PO fit, and employee voice behaviors through work engagement. Current Psychology, 41, 7762–7776. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01222-0

Kim, M., & Beehr, T. A. (2018). Organization-based self-esteem and meaningful work mediate effects of empowering leadership on employee behaviors and well-being. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 25(4), 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051818762337

Kovjanic, S., Schuh, S. C., & Jonas, K. (2013). Transformational leadership and performance: An experimental investigation of the mediating effects of basic needs satisfaction and work engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(4), 543–555. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12022

Kroon, B., Menting, C., & van Woerkom, M. (2015). Why mindfulness sustains performance: The role of personal and job resources. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 8(4), 638–642. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2015.92

Lawrie, E. J., Tuckey, M. R., & Dollard, M. F. (2018). Job design for mindful work: The boosting effect of psychosocial safety climate. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(4), 483–495. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000102

Liang, J., Farh, C. I., & Farh, J. L. (2012). Psychological antecedents of promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave examination. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0176

Lin, K. J., Savani, K., & Ilies, R. (2019). Doing good, feeling good? The roles of helping motivation and citizenship pressure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 104(8), 1020–1035. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000392

Liu, Y., He, H., & Zhu, W. (2020). Motivational analyses of the relationship between negative affectivity and workplace helping behaviors: A Conservation of Resources perspective. Journal of Business Research, 108, 362–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.019

MacCallum, R. C., Browne, M. W., & Sugawara, H. M. (1996). Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.2.130

Maslowsky, J., Jager, J., & Hemken, D. (2015). Estimating and interpreting latent variable interactions: A tutorial for applying the latent moderated structural equations method. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39(1), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025414552301

McAllister, D. J., Kamdar, D., Morrison, E. W., & Turban, D. B. (2007). Disentangling role perceptions: How perceived role breadth, discretion, instrumentality, and efficacy relate to helping and taking charge. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1200–1211. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1200

Meade, A. W., & Craig, S. B. (2012). Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 437–455. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028085

Muthén, B., & Muthén, L. (2017). Mplus. In Handbook of item response theory (pp. 507–518). Chapman and Hall/CRC.

Peng, A. C., & Zeng, W. (2017). Workplace ostracism and deviant and helping behaviors: The moderating role of 360 degree feedback. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(6), 833–855. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2169

Piccolo, R. F., & Colquitt, J. A. (2006). Transformational leadership and job behaviors: The mediating role of core job characteristics. Academy of Management Journal, 49(2), 327–340. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.20786079

Pierro, A., Presaghi, F., Higgins, T. E., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2009). Regulatory mode preferences for autonomy supporting versus controlling instructional styles. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 79(4), 599–615. https://doi.org/10.1348/978185409X412444

Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

Preacher, K. J., & Selig, J. P. (2012). Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Communication Methods and Measures, 6(2), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2012.679848

Reb, J., Narayanan, J., & Ho, Z. W. (2015). Mindfulness at work: Antecedents and consequences of employee awareness and absent-mindedness. Mindfulness, 6(1), 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0236-4

Riordan, C. M., Vandenberg, R. J., & Richardson, H. A. (2005). Employee involvement climate and organizational effectiveness. Human Resource Management, 44(4), 471–488. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20085

Scrimpshire, A. J., Edwards, B. D., Crosby, D., & Anderson, S. J. (2022). Investigating the effects of high-involvement climate and public service motivation on engagement, performance, and meaningfulness in the public sector. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 38(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-03-2021-0158

Semadeni, M., Withers, M. C., & Certo, S. T. (2014). The perils of endogeneity and instrumental variables in strategy research: Understanding through simulations. Strategic Management Journal, 35(7), 1070–1079. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2136

Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465. https://doi.org/10.2307/256865

Stride, C. B., Gardner, S., Catley, N., & Thomas, F. (2015). Mplus code for the mediation, moderation, and moderated mediation model templates from Andrew Hayes’ PROCESS analysis examples. http://www.figureitout.org.uk. Accessed May 2022.

Svendsen, M., Unterrainer, C., & Jønsson, T. F. (2018). The effect of transformational leadership and job autonomy on promotive and prohibitive voice: A two-wave study. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 25(2), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051817750536

Wallach, E. J. (1983). Organizations: The cultural match. Training and Development Journal, 37(2), 29–36.

White, K. M., Smith, J. R., Terry, D. J., Greenslade, J. H., & McKimmie, B. M. (2009). Social influence in the theory of planned behaviour: The role of descriptive, injunctive, and in-group norms. British Journal of Social Psychology, 48(1), 135–158. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466608X295207

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17(3), 601–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700305

Williams, L. J., Hartman, N., & Cavazotte, F. (2010). Method variance and marker variables: A review and comprehensive CFA marker technique. Organizational Research Methods, 13(3), 477–514. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428110366036

Wooldridge, J.M. (2008). Introductory econometrics: A modern approach (5th ed.). South-Western Cengage Learning.

Zhu, Y., & Akhtar, S. (2014). How transformational leadership influences follower helping behavior: The role of trust and prosocial motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(3), 373–392. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1884

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, L., Kao, KY., Hsu, HH. et al. Linking job autonomy to helping behavior: A moderated mediation model of transformational leadership and mindfulness. Curr Psychol 43, 19370–19385 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05716-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05716-z