Abstract

Cybersex encompasses a wide range of behaviors that use information and communication technologies as a means of access to obtain sexual gratification, a phenomenon that can take on problematic patterns. The main objective of the study is to propose a model that explains the extent to which online sexual activities and the negative emotionality associated with them can generate a tolerance phenomenon characterized by an increase in the frequency and intensity of cybersex behaviors. To this end, the Cybersex Behavioral Assessment Questionnaire was administered to a sample of 369 individuals. The results show that online sexual behavior and the presence of negative emotions during the performance of these activities influence the occurrence of tolerance, which is characterized by an increase and variety of activities with increasingly extreme typology. These findings may have implications for education and healthcare.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Drucker (1969) defined the knowledge society by establishing the essential characteristics of a new type of society in which knowledge becomes the basis of economic production and the greatest source of a country’s wealth, surpassing the value previously attached to the mere availability of information. In this context, information and communication technologies (ICT) played a very important role. They were the result of an unprecedented technological revolution, in which the development of the Internet and its services led to citizens having access to different tools for accessing content and communication, both synchronously and asynchronously. In this way, technologies were integrated into different areas of human life and played a leading role in areas such as democratic processes, commerce, culture, education, and also sex.

Cybersex, which some authors refer to as OSAs (online sexual activities), is therefore defined as the use of Internet tools to obtain sexual gratification (Wéry & Billieux, 2016), which covers a wide range of behaviors such as: 1) accessing and viewing pages with pornographic content (whether through videos, images, stories...), 2) using communication services and applications for that purpose (communication by microphone, videoconferences, webcam...) or, even, 3) accessing specific social networks for the search of sexual partners. This has led to a first classification (Shaughnessy et al., 2011) that divides this type of behavior into solitary arousal activities (p.e. watching pornographic videos), partner involvement activities (i.e. chatting with a partner online) or activities that do not produce arousal (i.e. searching for sexual information).

The consequences of the practice of cybersex are also varied and can also be positive or negative, sometimes conditioned by the motive behind its practice. On the one hand, obtaining sexual pleasure is not only the main motivation for engaging in cybersex but also its main positive effect, although others can be mentioned, such as its potential educational effect, its ability to promote more open sexual attitudes, its usefulness for learning about and exploring new sexual practices or as a coping strategy to reduce negative emotions (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2017; Brahim et al., 2019). On the other hand, these activities can lead to problematic situations (Ballester-Arnal et al., 2017; Bolshinsky & Gelkopf, 2019), for example: unwanted contacts that can generate from simple discomfort to traumatic effects; confusion of the characteristics and situations of pornography with real sexual practices, which can lead to the appearance of complexes or frustration due to the non-fulfilment of expectations; or compulsive and addictive use, with the consequent tolerance (anguish and anxiety about the impossibility of execution, the need to increase the frequency of access, progressive incorporation of increasingly extreme behaviours or neglect other life activities) and the appearance of symptoms typical of psychophysical pathologies such as dyspareunia, erectile dysfunction or alteration of the phases of sexual response (Blinka et al., 2022).

These circumstances make it particularly essential, albeit controversial and problematic, to distinguish between acceptable and problematic use, a difficulty that has so far been impossible to resolve. Firstly, because the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, in its latest edition (DSM-5), has eliminated the distinction between abuse and dependence, keeping only the categories of substance use disorders and substance-induced disorders, which also only refer to problems arising from substance-related disorders. Secondly, because although non-substance-related disorders are included, only pathological gambling is included in such a category (APA, 2013). And thirdly, because there is no specific correspondence between Compulsive Sexual Behaviour Disorder (CSBD), which does appear in the International Classification of Diseases (WHO, 2022) and an equivalent in the DSM-5, with the appropriateness of establishing the so-called “hypersexual disorder” having been analyzed (Mauer-Vakil & Bahji, 2020), whose final inclusion was rejected by the American Psychiatric Association (APA).

Apart from the above, and although the existence of differential characteristics between cybersex users and compulsive users in terms of arousal and reactivity has been empirically demonstrated, the theoretical study has been very limited (Brahim et al., 2019), although it has been corroborated that the existence of negative emotions is related to the use of cybersex, in an attempt to reduce its derived discomfort (Wéry et al., 2018).

Therefore, a number of questions arise that would need to be resolved: how could problematic use of cybersex practice be defined, what factors influence the occurrence of such problematic behavior, and is there a phenomenon of tolerance in cybersex practice similar to that which may occur in the case of substance addictions?

In this context, the purpose of this study attempts to provide an answer to these questions by proposing a model that explains to what extent online sexual activities and the negative emotionality associated with their practice can generate a phenomenon of tolerance similar to that of substance addictions, characterized by an increase in the frequency and intensity of cybersex behaviors.

Literature background

Despite the widespread practice of cybersex, it is difficult to pinpoint the percentage of users who engage in each type of activity, as, in addition to the component of social desirability that can alter responses when information is collected in this area, values can also differ greatly depending on the idiosyncrasies of each country and society, age ranges (young people tend to make greater use) and, especially, the behaviors under analysis. For example, the study by Döring et al. (2017) conducted in Sweden, Germany, Canada and the USA shows that up to 90% of the population searched for sexual information at some point in their lives using technological tools and that more than 77% accessed erotic or pornographic content.

Moreover, there is a major difficulty in approaching this type of study, since so far it has not been possible to establish a consensus on what is meant by problematic use of cybersex, not even in terms of conceptualization or diagnosis itself (Wéry et al., 2018).

Perhaps the most widespread is the one that defines the problem by bringing it closer to the frame of reference of substance addictions due to their similarity and even their interrelation (Soraya et al., 2022), but encompassing it in the category of the so-called non-substance addictions or behavioral addictions (Wang & Dai, 2020), which includes other addictive disorders such as pathological gambling or Internet addiction. However, in this case some authors (Pekal et al., 2018) no longer focus on the wide range of behaviors that cybersex can encompass, but rather on one of them, pornography viewing, which in this context has been referred to as Internet-pornography-use disorder.

Authors such as Brand et al. (2016), who share this approach, however, they are more specific and categorize the disorder within Internet use disorders. In fact, these authors have tested the I-PACE model, which aims to constitute itself as a theoretical framework to explain the processes underlying the development and maintenance of addictive use of certain applications or Internet sites that promote gaming, gambling, pornography viewing, shopping or communication.

There seems to be some consensus on the set of criteria present in problem behavior, which would include: loss of control, excessive time spent in sexual behaviors, and significant negative consequences in daily life (Wéry et al., 2018).

Hypothesis proposal

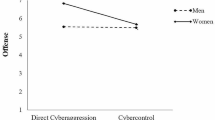

In this context, some studies have already tried to analyze the main behavior developed in the context of cybersex activities. For example, Shaughnessy et al. (2011) found that among solitary online sexual activities for the purpose of sexual satisfaction, viewing sexually explicit videos and photographs stood out, although there were statistically significant differences between men and women, since while 83.3% of men engaged in this practice, only 30.8% of women did so. Reading erotic material or masturbating while watching webcams were also mentioned in this context. Meanwhile, the main behaviour mentioned in terms of sexual activities with a partner was chatting and sharing sexual fantasies, which was practiced by 17.6% of men compared to 12% of women. Finally, when it came to non-arousal activities, the pattern was reversed, with accessing educational websites being the most common activity, although in this case it was performed to a greater extent by women (31.2%) than men (17.6%). Similarly, studies such as Studer et al. (2019) showed that cybersex use was especially frequent among young men and that there were differences in the frequency of use according to sexual orientation, as well as finding relationships between problematic use and sexual orientation. On this basis, the first hypothesis can be established:

-

H1. The frequency of sexual behavior will have a predictive effect on the emergence of tolerance generated as a consequence of repeated and problematic cybersex activities.

Apart from the behavioral effects of engaging in cybersex highlighted in previous studies, studies such as Chen et al. (2018) also examined how cybersex was a predictive effect by some emotional aspects. Thus, their study used structural equation modelling to examine the relationships between pornography craving, frequency and time of online sexual activity use, negative academic emotions and their interactions with respect to problematic cybersex use. It found that, within a sample of university students, about 20% of young people were in a risk/problematic use group, with subjects showing higher scores on all measures of severity, including problematic use of OSAs, amount and frequency of OSA use (suggesting some loss of control), pornography craving and negative academic emotion, which could be evidence of its role as an anxiety reducer. In the same vein, Castro-Calvo et al. (2018) adapted and tested in Spanish population the psychometric properties of the Sexual Addiction Screening Test (SAST; Carnes, 1983), one of the most widely used instruments to detect sexual addiction, finding that of the four factors assessed by this test, the “loss of control” factor was the one with the greatest explanatory capacity of the entire questionnaire (explaining 37.7% of the variance). Finally, Wéry et al. (2018) showed that negative emotions combined with negative urgency (acting impulsively in negative emotional situations) contributed to the use of cybersex as a way of coping with negative affect. From this, the following hypothesis can be suggested:

-

H2. The frequency of experiencing negative emotions will have a predictive effect on the emergence of tolerance, generated as a consequence of repeated and problematic cybersex activities.

In addition, as the aforementioned studies have found, there are three variables that should be taken into consideration, as they may condition the pattern of use and abuse of cybersexual behaviors.

Research model

In this framework, as stated by Franc et al. (2018), cybersex users explore and encounter a new world where the culture of cyberspace offers encouragement and acceptance of even their deepest fantasies, illustrating the relevance of the social factor in cybersex motives but also laying the groundwork for users themselves to venture into new environments and change their own online behavioral practices.

Therefore, the following model can be considered (Fig. 1), which establishes the relationships between the behavioral and emotional factors and the phenomenon of tolerance, understood as the quantitative and qualitative increase in the patterns that make up the practice of cybersex.

Method

Sample

A sample of 369 respondents was used for the study, with a slight majority of women (61.8%) as opposed to men or 0.5% transgender. The subjects of the study were divided into the following age groups: 18-20 years (48.8%), 21-25 years (24.7%), 26-30 years (7.1%), and > 30 years (19.3%). The respondents defined themselves as mostly heterosexual (76.6%), following bisexual (18.8%), homosexual (4.3%), and asexual (0.3%). The vast majority lived in Spain (69.4%).

Notably, when considering the influence of sexual orientation on sexual behaviour, the two groups did not differ significantly. Thus, in the group of university students, the majority defined their sexual orientation as heterosexual (82.1%), as in the group of users of cybersex channels, although in this case the percentage was slightly lower (70%). In the student group, 3% defined themselves as homosexual and 14.4% as bisexual, while in the cybersex group, 6% defined themselves as homosexual and 24% as bisexual. Only one person defined himself as asexual, in this case belonging to the group of university students.

Instrument

To collect the data we used the Behavioral Evaluation Questionnaire of Cybersex, designed ad-hoc for this research and composed of five sections and a final open-ended question for observations in which the participant could include any type of information or comment.

Thus, first section collects personal and sociodemographic information about the subject and is composed of four items: sex, age, sexual orientation and place of residence.

The following four sections are answered according to a Likert-type response scale with four response options: 1.- Almost never, 2.- A few times, 3.- Some times, 4.- Many times, although to avoid the subjectivity of interpretation of the different options they have been operationalized as follows: 1.- Almost never (once a month or less frequently), 2.- Few times (between one and three times a month), 3.- Sometimes (about once a week) and 4.- Many times (two or more times a week).

Second section, composed of five items, evaluates behaviors related to cybersex performed by the subject, including: access to applications with adult content (websites, forums, etc.); contacts through chat, messaging or similar writing applications for purposes of sexual satisfaction (stories, written conversations, exchange of photos, etc.); contact through calls (phone calls, microphone, etc.) for purposes of sexual satisfaction (cybersex through verbal contact).); contact through calls (phone calls, microphone, etc.) for the purpose of sexual gratification (cybersex through verbal contact); contact through video calls (Skype, Telegram, WhatsApp, etc.) for the purpose of sexual gratification (cybersex through webcam contact) and arranging online face-to-face sexual meetings.

Third section, also composed of five items, analyses the emotional states of the subject while engaging in cybersex practices and collects information on whether the person has felt uncomfortable before situations or communicative exchanges for sexual purposes, whether he/she has felt fear, guilt, or shame, whether he/she believes to have lost control over the frequency of use, or whether he/she believes to have lost control over the contents or practices performed.

Fourth section, also articulated around five items, examines the changes produced by the realization of cybersex behaviors and asks if the person has known new sexual behaviors or practices on the Internet channels, if he/she has known new sexual practices of his/her liking, if he/she has varied the sexual behaviors or practices performed compared to the previous ones, if he/she perceives the type of sexual practices he/she deals with on the Internet as “stronger” or more intense than those previously practiced and if his/her sexual practices on the Internet have led him/her to try to know more different types of sexual practices.

Fifth section, composed of two items with specifically educational and preventive purposes, asks whether the subject has ever contacted a minor or attempted to contact him/her in a chat room or Internet channel of a sexual nature and whether he/she has ever detected the presence of minors (or seen subjects identified as such) in a chat room or Internet channel of a sexual nature.

Procedure

The questionnaire application procedure followed two different routes according to the selected study samples. On the one hand, it was implemented as a written and structured interview to users of cybersex channels, obtaining this part of the sample through chat with sexual content (n = 167) and on the other hand to university students (n = 202). In both cases they were asked to participate voluntarily, and they had to accept the participation clause to answer the questionnaire. This double sample was intended to increase the variability of response and to select subjects in the context where this type of behavior occurs most regularly.

In all cases, anonymity and compliance with the Data Protection Law were guaranteed, as well as the confidentiality of the answers given, following the ethical principles established in this type of study. In fact, the questionnaire specifically included a clause in which the subject was provided with information about the objective of the study and the guarantees when carrying it out, after which the respondent agreed to participate in the research and then went on to answer the questionnaire.

Results

Descriptive analysis was performed with SPSS v.27 and SmartPLS 3 to examine the relationships in our conceptual model using partial least squares equation modelling (PLS-SEM).

Data

Initially, descriptive analyses were performed on the variables that made up the behavioral and emotional factors. As can be seen in Table 1, the most frequent behavior (considering the sum of the values sometimes and very often) is access to adult content applications, such as pornographic web pages, storytelling, or forums, followed by direct contact through written communication applications. Likewise, negative emotions. Likewise, in the emotional aspect, the feeling of discomfort, loss of control over the frequency of access and fear are the negative emotions most frequently experienced by people who have practiced cybersex behaviors.

Measurement model

A two-stage procedure was used to analyze the results of the proposed model (Hair et al., 2011): (1) reliability and discriminant validity and (2) validation of hypotheses. Below, the results obtained in each of these phases are described.

At first, for reliability calculations, we use the two-stage procedure of Anderson and Gerbing (1988) method to calculate the convergent validity and discriminant validity of the constructs. For this purpose, construct reliability was tested by Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), Cronbach’s alpha, Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) were calculated.

The results indicate that most loadings factor exceed 0.7, and the corresponding t-statistic shows that it is statistically significant (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Nevertheless, loading factors higher than 0.40 are also acceptable if the AVE of the construct is higher than 0.50 (Hair et al., 2014). For this reason, the results suggesting internal consistency criteria. Furthermore, internal consistency ideally requires CR values above 0.70 (Hair et al., 2014). In this case, the results satisfy such criteria.

Finally, convergent validity requires an AVE for each construct greater than 0.50 (Hair et al., 2011). In this study, all the results satisfy this criterion. Table 2 shows the psychometric properties of the measurement model.

Subsequently, the Fornell-Larcker criterion (1981) and the Heterotrait-Monotrait Correlation Ratio Test (HTMT) criterion (Henseler et al., 2015) were used to assess discriminant validity (Table 3). Fornell and Larcker’s criterion stated that squared AVE values should be higher than intercorrelation values (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Furthermore, HTMT criteria confirmed that all HTMT values are below the threshold of 0.90 (Hair et al., 2019) concluding the discriminant validity of the constructs. Finally, we tested the model for common bias method (Podsakoff et al., 2003) by adopting the full collinearity approach (Kock, 2015); the results shows that the highest internal VIF was 1.65, below the suggested limit of 5 and therefore, the proposed model is valid.

Structural model

The hypotheses proposed in this paper were evaluated by means of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM). This method was chosen mainly due its ability to estimate complex models with many variables, indicators, and structural paths, without imposing distributional assumptions on the data (Prentice et al., 2023). In this way, to examine the quality of the structural model, we assessed the coefficient of determinants (R2), the predictive relevance (Q2) and the magnitude and significance of the path coefficients (Sciarelli et al., 2022). In this case, R2 value for the dependent variable exceeded the values of 0.26 suggested by Cohen (1988), indicating a reliable predictive power of the model. In addition, Q2 value of the predictive significance is greater than 0, indicating that the structural model has a satisfactory predictive significance for the dependent variables (Sciarelli et al., 2022). For this purpose, we use bootstrap procedure with 10,000 resamples was used to assess the significance of the path coefficients (Hair et al., 2019). Table 4 shows the main results of the structural model.

The above results confirm that the hypotheses put forward are statistically significant. Specifically, hypothesis H1, according to which frequency in sexual behavior influences the occurrence of tolerance, generated as a consequence of repeated and problematic practice of cybersex activities, can be confirmed (β = 0.479; p < 0.01). Thus, a greater frequency in the practice of cybersex activities seems to lead to a greater tolerance effect, which implies a greater discovery of sexual practices and a search for them, these being defined by a more extreme character.

Furthermore, hypothesis H2, which proposes that the frequency of experiencing negative emotions influences the appearance of tolerance, generated as a consequence of the repeated and problematic practice of cybersex activities, is confirmed (β = 0.270; p < 0.01). In this case, there is a paradoxical effect that experiencing negative emotions facilitates the process of tolerance, increasing the frequency and intensity of cybersex behaviors.

Finally, we cannot ignore the fact that, as expected, control variables such as sex, age and sexual orientation influence the factors analyzed. As can be seen, both sex and age condition the type of behaviors performed and the emotions perceived, but not the phenomenon of tolerance, while sexual orientation conditions the behaviors performed and the phenomenon of tolerance, although it does not seem to be relevant for considering the emotions generated.

Discussion and conclusions

This fact can be easily understood in a social context such as the current one, where information and communication technologies have been integrated into many areas, leading to a considerable increase in the number of communication channels that facilitate the performance of various behaviors.

The results obtained in the present study show the existence of this practice to different degrees and reveal how it affects the emotional state of the subject. But they also seem to conclude the existence of a phenomenon of gradual increase, defined by a greater frequency in the practices performed and by the discovery and performance of new cybersex practices with an increasingly intense content, which derives both from the compulsive use of the initial practices and from the presence of negative emotions associated with these behaviors.

The first effect that has been observed, which is quite logical in nature, highlights how engaging in cybersex practices can generate a gradual effect that progresses to a compulsive behavior pattern, determined firstly by the increase in the behaviors themselves and, secondly, by the variation in the behaviors themselves. These results are consistent with those obtained by LeBlanc and Trottier (2022), who found that both men and women with problematic pornography consumption patterns had higher scores on aspects such as frequency, but also on variables related to motives for use (emotional avoidance, sexual curiosity and sexual pleasure). This same pattern of increase was also found by Kingston et al. (2008), who demonstrated how the frequency of access and the type of pornography consumed was a risk factor that could even predict recidivism in a sample of subjects convicted of child sexual abuse.

The second effect may be more interesting, as it presents the paradoxical effect of a subject performing a behavior that seems to be generating negative emotions with increasing frequency and intensity. However, two aspects should be considered at this point. First, the relationship of pre-existing negative emotions with compulsive behavior, since it is not only a question of analyzing whether people who show a pattern of abuse of cybersex practices suffer more negative emotions than people who do not, but also of knowing what drives them to do so. In this sense, it may be interesting to mention the study by Wehden et al. (2021), which determined the existence of correlations between levels of depression, anxiety and loneliness and problematic use of sexually explicit content on the Internet, although it would be necessary to deepen the meaning of these relationships. Also the study by Castro et al. (2018) is along the same lines, finding that aspects such as social anxiety could predict pathological internet use in relation to cybersex behaviors. In the same line, Odlaug et al. (2013) found that university students who manifested compulsive sexual behavior had more anxiety disorders and higher levels of stress than those who did not show compulsive behavior.

On the other hand, we tried to verify if the increase of negative emotions suffered by the subjects themselves during the practice of cybersex sessions is related to the increase of the tolerance effect. The results obtained seem to indicate that this is the case, which could be explained by a maladaptive psychological process that originates when trying to reduce the negative emotions, both previous and supervening, as a result of the continuous practice. Thus, the subject enters a cycle in which the behavior that attempts to reduce the discomfort worsens the situation, because although it temporarily alleviates the existing discomfort, it generates new negative emotions that increase it once the gratifying effect disappears, which aggravates the situation and perpetuates its practice. In this regard, Kohut and Stulhofer (2018) demonstrated that negative mental states could precede the use of pornography, which in this case would be used with the aim of obtaining rewarding effects to compensate for them. This is also consistent with the findings obtained by Hegbe et al. (2021), who found significant differences between subjects with and without sexual addiction in various factors of emotional dysregulation. In fact, the factor of non-acceptance of emotional response, especially with regard to negative affect, had a predictive value for sexual addiction. Sexual addiction could, therefore, be considered as an inappropriate strategy adopted by subjects to cope with their difficulty or inability to accept their emotional response, especially while experiencing negative affect.

The most relevant findings of the present study are along these lines, which show how emotions and, more specifically, emotional regulation skills are of central importance in the psychological process underlying cybersex practices. This contributes not only to explaining the complex psychological phenomena that are set in motion in the processes of compulsion or addiction, but also allows the design of clinical and educational intervention strategies that may be of interest to slow down the progression towards problematic behavior. All this, however, does not preclude considering other input variables such as: craving for pornography, difficulties in establishing intimate bonds, motives for use or sexual desire (Brahim et al., 2019; Weinstein et al., 2015); which can also function as risk factors or input variables, although they were not considered in the present research.

Sexual orientation was considered as a relevant input variable, which seems to affect the frequency of the behaviors performed and the tolerance effect itself. These findings are consistent with those of Mathy (2007), who anticipated that sexual orientation might play an important moderating role on behaviors, and Scandurra et al. (2022), who observed that non-heterosexuality increased participation in solitary online sexual activity for arousal, but not with a partner. Therefore, it seems likely that such an increase in frequency may promote the tolerance effect to some extent. However, it would be interesting to analyze why in this case it does not seem to be related to an increase in the generation of negative emotions.

In this way, and regarding the theoretical implications of the study, the present research contributes to scientific progress by analyzing the role of emotions and confirming the existing association between these and problematic behaviors in practicing cybersex. However, these results, in line with those of other similar studies showing an association between engaging in online sexual activities and problematic aspects or functional impairment (Wéry & Billieux, 2015), can be presented as indications of a possible explanation, but not determined as causal, as there is no consensus in the literature regarding the causal explanation, the conceptualization and labeling of the disorder, or its diagnosis and assessment.

In terms of practical implications, relevant information is provided both for the prevention of the problem and for the detection and psychological intervention of cybersex abuse problems. Thus, the focus is placed on the practices and, especially, on the emotional regulation processes existing before and during cybersex practices, on the basis that a correct emotional regulation could minimize the problematic aspect by reducing the behavior and slowing down the mechanism that leads towards an evolution of progressive increase (Wéry et al., 2018).

The contextual implications stem from the previous ones. Thus, in the first place, the results have a certain relevance that involves educational environments. If we take into account the increasingly early nature of access to on-line sexual content and practices, schools cannot be abstracted from this phenomenon, being necessary for them to know the problematic signs and, even, that through information and emotional regulation programs, they can carry out interventions that prevent the progression to problematic patterns of use (Cashwell et al., 2017). Second, they may also have relevance in the clinical context. Thus, the fundamental role of emotions in this type of practice should be taken into account when planning therapy, since emotional regulation strategies will increase the effectiveness of psychological treatments, as new generation therapeutic approaches (Hegbe et al., 2021) that consider this aspect have shown.

Finally, some limitations of the study should be mentioned, the most important ones being those derived from the small, localized and specific nature of the sample. In this sense, it would be interesting to broaden it by creating different groups according to their non-problematic and problematic use, which would allow much more precise comparisons with a higher degree of validity. In addition, it should be noted that this is not an experimental study, so the causal and explanatory relationship of the phenomenon cannot be established, although it may provide certain indications in that direction.

In terms of future research lines, it would be desirable to continue the analytical study of the various psychological processes, both behavioral and emotional, that are involved in cybersex practices. This is particularly interesting from a clinical point of view, since it would allow us to analyze them in relation to the various psychophysiological responses that the subject develops in this type of situation.

On the other hand, it could be interesting to analyze these differences considering variables such as gender, age or sexual orientation (Scandurra et al., 2022), but also other related variables such as moral and religious beliefs, socioeconomic context or personal values. In this sense, and beyond confirming their existence, it is particularly important to try to explain the reason for the differences obtained according to belonging to different groups.

Among these new variables, it would be relevant to highlight the type of relationship the subject has (if he or she is in one): single, with an exclusive partner, with an open partner, with several partners... Not surprisingly, the studies by Wéry and Billieux (2016) already found that there could be a problematic use of these channels, which would be greater among people without a partner than among people who consensually engage in these practices with their sexual partners, which could reveal differentiated psychological mechanisms depending on aspects such as motivation or expectations of use.

Data availability

The data will be availability after paper acceptation.

References

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modelling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

APA (American Psychiatric Association). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Association.

Ballester-Arnal, R., Castro, J., Gil-Llario, M. D., & Gil-Julia, B. (2017). Cybersex addiction: A study on Spanish college students. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 43(6), 567–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2016.1208700

Blinka, L., Ševčíková, A., Dreier, M., Škařupová, K., & Wölfling, K. (2022). Online sex addiction: A qualitative analysis of symptoms in treatment-seeking men. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 907549. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.907549

Bolshinsky, V., & Gelkopf, M. (2019). Motives and risk factors of problematic engagement in online sexual activities. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 26(3-4). https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2019.1645062

Brahim, F. B., Rothen, S., Bianchi-Demicheli, F., Courtois, R., & Khazaal, Y. (2019). Contribution of sexual desire and motives to the compulsive use of cybersex. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(3), 442–450. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.47

Brand, M., Young, K. S., Laier, C., Wölfling, K., & Potenza, M. N. (2016). Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific internet-use disorders: An interaction of person-affect-cognition-execution (I-PACE) model. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 71, 252–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.033

Carnes, P. J. (1983). Out of the shadows: Understanding sexual addiction. CompCare Publishers.

Cashwell, C., Giordano, A., King, K., Lankford, C., & Henson, R. (2017). Emotion regulation and sex addiction among college students. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 15, 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-016-9646-6

Castro, J. A., Vinaccia, S., & Ballester-Arnal, R. (2018). Ansiedad social, adicción al internet y al cibersexo: su relación con la percepción de salud. Terapia Psicológica, 36(3), 134–143. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-48082018000300134

Castro-Calvo, J., Ballester-Arnal, R., Billieux, J., Gil-Julia, B., & Gil-Llario, M. D. (2018). Spanish validation of the sexual addiction screening test. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(3), 584–600. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.57

Chen, L., Ding, C., Jiang, X., & Potenza, M. N. (2018). Frequency and duration of use, craving and negative emotions in problematic online sexual activities. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 25(4), 396–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720162.2018.1547234

Cohen, J. (1988). Set correlation and contingency tables. Applied Psychological Measurement, 12(4), 425–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662168801200410

Döring, N., Daneback, K., Shaughnessy, K., Grov, C., & Byers, E. S. (2017). Online sexual activity experiences among college students: A four-country comparison. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(6), 1641–1652. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0656-4

Drucker, P. (1969). The age of discontinuity. Pan Books.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

Franc, E., Khazaal, Y., Jasiowka, K., Lepres, T., Bianchi-Demicheli, F., & Rothen, S. (2018). Factor structure of the Cybersex Motives Questionnaire. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(3), 601–609. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.67

Hair, J. F., Jr., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed, a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/mtp1069-6679190202

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/ebr-11-2018-0203

Hegbe, K., Réveillère, C., & Barrault, S. (2021). Sexual addiction and associated factors: The role of emotion dysregulation, impulsivity, anxiety and depression. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 47(8), 785–803. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2021.1952361

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variancebased structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135.

Kingston, D., Fedoroff, P., Firestone, P., Curry, S., & Bradford, J. (2008). Pornography use and sexual aggression: The impact of frequency and type of pornography use on recidivism among sexual offenders. Aggressive Behavior, 34, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20250

Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of E-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

Kohut, T., & Stulhofer, A. (2018). Is pornography use a risk for adolescent well-being? An examination of temporal relationships in two independent panel samples. PLoS One, 13(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202048

LeBlanc, C., & Trottier, D. (2022). Utilisation problématique de pornographie en ligne chez les hommes et les femmes: Facteurs discriminants et prédictifs. Sexologies, 31, 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sexol.2022.07.003

Mathy, R. (2007). Sexual orientation moderates online sexual activities. In M. Whitty, A. Baker, & J. Inman (Eds.), Online Matchmaking (pp. 159–177). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230206182_12

Mauer-Vakil, D., & Bahji, A. (2020). The addictive nature of compulsive sexual behaviours and problematic online pornography consumption: A review. Canadian Journal of Addiction, 11(3), 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/CXA.0000000000000091

Odlaug, B., Lust, K., Schreiber, L., Christenson, G., Derbyshire, K., Harvanko, A., Golden, D., & Grant, J. (2013). Compulsive sexual behavior in young adults. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 25(3), 193–200.

Pekal, J., Laier, C., Snagowski, J., Stark, R., & Brand, M. (2018). Tendencies toward internet-pornography-use disorder: Differences in men and women regarding attentional biases to pornographic stimuli. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(3), 574–583. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.70

Podsakoff, P., Mackenzie, S. B., Jeong-Yeon, L., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Prentice, C., Loureiro, S. M., & Guerreiro, J. (2023). Engaging with intelligent voice assistants for wellbeing and brand attachment. Journal of Brand Management, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-023-00321-0

Scandurra, C., Mezza, F., Esposito, C., Vitelli, R., Maldonato, N. M., Bochicchio, V., Chiodi, A., Giami, A., Valerio, P., & Amodeo, A. L. (2022). Online sexual activities in italian older adults: The role of gender, sexual orientation, and permissiveness. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 19, 248–263. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-021-00538-1

Sciarelli, M., Prisco, A., Gheith, M. H., & Muto, V. (2022). Factors affecting the adoption of blockchain technology in innovative Italian companies: An extended TAM approach. Journal of Strategy and Management, 15(3), 495–507. https://doi.org/10.1108/jsma-02-2021-0054

Shaughnessy, K., Byers, E. S., & Walsh, L. (2011). Online sexual activity experience of heterosexual students: Gender similarities and differences. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(2), 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9629-9

Soraya, S., Rashedi, V., Saeidi, M., Hashemi, P., Hadi, F., Ahmadkhaniha, H., & Shalbafan, M. (2022). Comparison of online sexual activity among iranian individuals with and without substance use disorder: A case-control study. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 889528. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.889528

Studer, J., Marmet, S., Wicki, M., & Gmel, G. (2019). Cybersex use and problematic cybersex use among young Swiss men: Associations with sociodemographic, sexual, and psychological factors. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(4), 794–803. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.69

Wang, J., & Dai, B. (2020). Event-related potentials in a two-choice oddball task of impaired behavioral inhibitory control among males with tendencies towards cybersex addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(3), 785–796. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00059

Wehden, L., Reer, F., Janzik, R., & Quandt, T. (2021). Investigating the problematic use of sexually explicit internet content: A survey study among German internet users. Sexual Health & Compulsivity, 28(3-4), 127–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/26929953.2022.2032514

Weinstein, A., Zolek, R., Babkin, A., Cohen, K., & Lejoyeux, M. (2015). Factors predicting cybersex use and difficulties in forming intimate relationships among male and female users of cybersex. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 6, 54. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00054

Wéry, A., & Billieux, J. (2015). Problematic cybersex: Conceptualization, assessment, and treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.11.007

Wéry, A., & Billieux, J. (2016). Online sexual activities: An exploratory study of problematic and non-problematic usage patterns in a sample of men. Computers in Human Behavior, 56, 257–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.046

Wéry, A., Deleuze, J., Canale, N., & Billieux, J. (2018). Emotionally laden impulsivity interacts with affect in predicting addictive use of online sexual activity in men. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 80, 192–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.10.004

WHO (World Health Organization). (2022). International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics. World Health Organization.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. No applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have contributed equally to this paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

None.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cervero, A., Castro-Lopez, A., Alvarez-Blanco, L. et al. Explanatory factors for problematic cybersex behaviour: the importance of negative emotions. Curr Psychol 43, 18109–18118 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05639-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05639-9