Abstract

Male suicide rates represent a public health crisis. In almost every country, more men die by suicide than women and suicide is a leading cause of death for men in the United States and the United Kingdom. Evidence suggests that men are less likely than women to access professional support for suicidal distress. Ensuring more men access support is a critical component of suicide prevention. This study explores responses from 725 men, worldwide, who have attempted suicide or have had thoughts of suicide in the last year, to an open-text question about the barriers they experience to accessing professional support. Using a thematic analysis, results reveal the multifaceted barriers some men experience regarding a lack of motivation, a lack of psychological capability, and/or a lack of physical/social opportunity to access support. Findings suggest that many men have sought support but had negative experiences and that many others want help but cannot access it. Barriers include prohibitive costs and waiting times; potential costs to identity, autonomy, relationships and future life opportunities; a lack of perceived psychological capability; a lack of belief in the utility of services and a mistrust of mental health professionals. Findings suggest the importance of examining the role of male gender in male help-seeking behaviours. We suggest 23 recommendations for services and public health messaging to increase men's help-seeking behaviours.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Male suicide rates represent a public health crisis. In the United States, nearly 80% of suicide deaths in 2019 were male (Fowler et al., 2022). Similarly, in the UK, more men have died by suicide than women each year since records began in 1861 (Seager, 2019). Understanding why men are at such a heightened risk of suicide is a critical question for researchers (Möller-Leimkühler, 2003). Men’s perceived reluctance to seek professional support has been identified as contributing to the higher male suicide rate but needs closer examination (Mallon et al., 2019).

Effective help-seeking can prevent mental health challenges from escalating and protect against suicide (Addis & Mahalik, 2003; Cornally & Mccarthy, 2011; Mok et al., 2021; Reynders et al., 2015). Two systematic reviews have identified dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) and restricting access to the means of suicide as being suicide protective (D'Anci et al., 2019; Zalsman et al., 2016). Additionally, Zalsman et al. (2016), in their ten-year systematic review of suicide prevention strategies, found evidence that supports Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for reducing suicidal thoughts, lithium for reducing suicidal ideation in people with mood disorders, and valproate for people with bipolar disorder. This evidence suggests that certain therapeutic and medical interventions hold promise in reducing suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Therefore, encouraging more men to seek professional help and access these interventions could help mitigate male suicide risk.

Quantitative research suggests that men are less likely to access professional mental health support than women (Galdas et al., 2023). While not exploring suicide risk specifically, in the United States women with a mental health diagnosis are 1.6 times more likely than men to receive mental health support in a year (Wang et al., 2005). Similarly, in the UK, the ‘Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey’ found that women were 1.58 more likely to access mental health treatment than men (McManus et al., 2007). In terms of suicidal populations, Luoma et al. (2002) 40-study review found that women are more likely to be in lifetime contact with mental health services compared to men before a completed suicide. In a UK study, only 25% of people who died by suicide had contact with mental health services in the year before they died, and the people who had no contact were more likely to be male with no mental health diagnosis (Hamdi et al., 2008). In Tang et al.’s (2022) systematic review of 67 studies of people who died by suicide but who did not have contact with mental health services, men were consistently associated with not accessing support. Similarly, Walby et al. (2018)’s systematic review and meta-analysis showed men were significantly less likely to have had contact with mental health services than women before a suicide. This quantitative work suggests men who are suicidal seek mental health support less than women, and we urgently need to understand why.

Explanations for reduced help-seeking in men have often centred on the influence of masculine norms and social expectations for men to suppress emotions, deny pain, and cope independently (Keohane & Richardson, 2018; Kiamanesh et al., 2015; Oliffe et al., 2017; Galdas et al., 2023; Swami et al., 2008). Scholars suggest some men may see help-seeking as a transgressive act that communicates weakness, consequently, men may fear stigma and judgement from others if they seek support (Kõlves et al., 2013). Cultural expectations for masculinity and societal understandings of suicidal distress are not fixed or unchanging; rather, they will vary across locations and this variation will moderate how men in different environments interpret their pain and the choices they make in response to it (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005; Hjelmeland, 2013). Qualitative methodologies can help researchers to explore male understandings of help-seeking through their subjective perspectives and illuminate aspects of these dynamics. To this end, Hoy (2012) conducted a meta-ethnography of 51 qualitative studies exploring male perspectives on seeking support for psychological distress. While not specific to men who are suicidal, Hoy identified four barriers: 1) negative social stigma, 2) unease towards medical experts and medications, 3) challenges in expressing emotional problems, and 4) a desire to manage challenges independently. Some of these findings are supported in the relatively small qualitative literature regarding help-seeking within male suicide-specific populations. A qualitative study with 18 men in Australia suggested that some men can reject services that frame suicidal pain as a mental illness (River, 2018). Rasmussen et al. (2018) conducted a psychological autopsy study on ten suicide deaths in men aged 18 and 30 and suggested help-seeking was rejected by the men who died because it would mean not living up to familial and societal expectations, represented weakness, and a failure of personhood. Oliffe et al. (2020) study with bereaved loved ones of twenty men who died by suicide found that some men concealed their pain and never sought professional support; other men did go for help but experienced ineffectual support, primarily again because of a focus on medication, an approach rejected by men in this sample. Cleary (2017) conducted a follow-up study seven years after 52 men made a medically serious suicide attempt and found that only 20% of men accessed follow-up psychiatric aftercare, and almost half made another attempt. Cleary suggested that men doubted the effectiveness of psychiatric interventions, were reticent to disclose distress, and preferred self-medication through alcohol and drugs. Other scholars have suggested a link between a reluctance to seek professional help and some men adopting alternative coping strategies to mitigate their distress—such as alcohol and substance abuse – which may compound some men’s pain and potentially elevate suicide risk over the long term (De Leo et al., 2005; Keohane & Richardson, 2018).

Understanding the barriers that men who are suicidal experience around accessing professional support has been identified as a critical issue for male suicide prevention (Mallon et al., 2019; Oliffe et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2022). Current evidence suggests that some men who are suicidal are reticent to access help, potentially because of masculine norms, while other men do seek support, but experience help that is unhelpful (Oliffe et al., 2020; Bennett et al., 2023a, b; Tryggvadottir et al., 2019). The current literature on male help-seeking is relatively small, and primarily drawn from men with different mental health challenges and therefore lacks exploration of men who are suicidal specifically. The literature specific to male suicide and male help-seeking is based on quantitative methods, bereaved populations, or very small qualitative samples. Scholars have called for more qualitative work that can explore the root causes of male help-seeking reluctance and how masculine norms may impact how men recognize suicidal crises within themselves and their decisions concerning how to act on and manage their feelings of suicide (Galdas et al., 2005; Keohane & Richardson, 2018; Milner & De Leo, 2010).

This study aims to build on what is already known and qualitatively explore, across a large sample, specifically drawn from men who are currently or recently suicidal, potential barriers around accessing professional support. Like other qualitative work in this area, the rationale for this study is, as Hoy describes, “a pragmatic one” (p. 204). Building a better understanding of the obstacles men who are suicidal currently face in seeking help can inform the development of new interventions for men. By exploring barriers through a qualitative methodology, across a large sample and direct from men who are currently or recently suicidal, we hope to elicit richer data than currently available regarding the meanings, perceptions, and experiences of men who are suicidal around seeking professional support. In short, we hope these findings can help policymakers, service providers, and researchers develop interventions to increase the help-seeking behaviors of men who are suicidal.

Methods

The data in the present study are a subset of open-text responses from a larger survey (n = 3,134) conducted from March to October 2021 on male suicide risk and recovery factors. Ethical approval was granted by the College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences (MVLS) at the University of Glasgow (ID 200200128). All participants gave informed consent before taking part.

Participant recruitment

Men around the world, aged 18 and over, were invited to answer a set of questions relevant to male suicide risk and recovery. Questions covered issues concerning adverse childhood experiences, attitudes and relationship to self and emotions, social isolation and loneliness, mental pain, suicide risk, and protective factors. The survey was built and hosted on online survey software (JISC). A pilot study was run with men with lived experience to provide feedback on clarity, accessibility, and sensitivity (n = 6). Participant recruitment ran from April to October 2021 and was based on adverts shared with national and local mental health/suicide prevention organisations; sports groups; depression/male support groups; community faith groups; businesses; mental health bloggers; online adverts; Facebook and Reddit groups, and the research team’s personal networks.

Measures

This study focused on responses to the following open-text question about professional help-seeking. Participants were initially asked: “How likely would you be to seek professional help for your mental health if you felt you needed it right now?” Participants could respond using a 3-point Likert-type scale of ‘Not likely’, ‘Somewhat likely’, ‘Very likely.’ Participants were then asked: “If you answered that you would not be likely what would be some of the barriers to you accessing professional support?” Participants could respond in an expanding, limitless text box.

To measure participants' past thoughts of suicide, respondents were asked ‘Have you ever thought of taking your life, but not actually attempted to do so?’ Participants could respond ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. Participants who answered ‘Yes’, were then asked, ‘When did you last think about taking your life?’ Participants could answer based on a 3-point Likert-type scale of ‘The past week’, ‘The past year’, or ‘Longer ago.’

To measure past suicide attempts participants were asked: ‘Have you ever made an attempt to take your life?’ Participants could respond ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. Participants who answered ‘Yes’, were then asked, ‘When did you last attempt to take your life?’ Participants could answer based on a 3-point Likert-type scale of ‘The past week’, ‘The past year’, or ‘Longer ago.’ To measure intent participants were asked with regards to their most recent attempt, ‘Which of the following statements best applies to you?’ and could select either: ‘My wish to die during the last suicide attempt was low; My wish to die (…) was moderate; or, My wish to die (…) was high.’ Participants were also asked ‘How many times have you made an attempt to take your life?’.

Data were collected during the Covid-19 pandemic and to measure the impact of the pandemic on respondents' well-being, participants were asked: ‘How much does Covid-19 affect your life?’; ‘How much does Covid-19 affect your financial situation?’; and ‘How much does Covid-19 affect your mental wellbeing?’ Participants could reply to each question on a Likert-type scale from ‘0 – no effect at all’ to ‘10—Severely affects my life.’

Sample and inclusion criteria

This study included men who had experienced thoughts of suicide and/or attempted suicide in the past week or year. Study inclusion and segmentation were based on the following criteria:

-

Suicide Ideation Group = Participants answered ‘Yes’ to having thoughts of suicide within ‘The past week’ or ‘The past year’ but ‘No’ to suicide attempt.

-

Suicide Attempt Group = Participants answered ‘Yes’ to a previous suicide attempt and either, ‘Yes’ to suicidal ideation within the last week or year, or ‘Yes’ to a suicide attempt within the last week or year.

Participant demographics

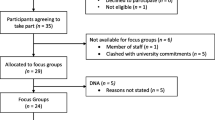

This study comprised 725 men of whom 440 had never attempted suicide but had thoughts of suicide in the past week (n = 264; 36%), or the past year (n = 176; 24%) (Suicide ideation group; n = 440; 61%); and 285 men who had attempted suicide, either in the past week (n = 12;2%), the past year (n = 84;12%) or longer ago but had thoughts of suicide in the past week (n = 137; 19%), or the past year (n = 52; 7%) (Suicide attempt group; n = 285; 39%). Of the suicide attempt group, 29% had made 1 attempt, 47% had made between 2 and 4 attempts, and 21% had made 5 or more attempts. Regarding suicidal intent, 59% stated that their wish to die during their most recent attempt was high; 32% said moderate; and 8% said low. See Fig. 1 for an overview.

Participants came from 57 different countries; however, the sample was predominately from Western locations with the highest responses—based on the United Nations classification of continents – from Northern America (40%), Northern Europe (34%), Western Europe (8%), Australia and New Zealand (5%), and Eastern Europe (3%) (United Nations, 2023). Based on the World Bank Income classifications 93% of participants were from higher-income countries, 5% from upper-middle, and 2% from lower-middle-income countries (World Bank, 2023).

Participants were predominately aged 18–30 years (overall sample = 72%; Ideation = 74%; Attempt = 71%), white (overall sample = 78%; Ideation = 80%; Attempt = 75%), single (overall sample = 71%; Ideation = 73%; Attempt = 68%), straight (overall sample = 72%; Ideation = 74%; Attempt = 67%), employed full-time (overall sample = 38%; Ideation = 39%; Attempt = 37%), and financially doing alright (overall sample = 35%; Ideation = 37%; Attempt = 32%). Of the sample, 47% identified as having a mental health diagnosis (Ideation = 36%; Attempt = 63%). The average age of the total sample, ideation group, and attempt group was 28. The mean impact of Covid-19 on participant's lives was 6 out of 10 (SD = 4.99); impact on wellbeing was 5 out of 10 (SD = 5.01); and 1 out of 10 for impact on financial situation (SD = 3.46). See Table 1 for a full breakdown of participant demographics.

Data analysis

This study applied a thematic analysis to the data to explore the barriers participants experienced in accessing professional support. Responses were analysed using a critical-realist, inductive thematic approach based on Braun and Clarke’s (2006) methodology. Text was analysed at both a semantic and latent level for patterns of meaning across the data, as interpreted by the authors of this study (Terry et al., 2017).

Responses were downloaded into an Excel spreadsheet and coded as either ‘Suicide ideation group’ or ‘Suicide attempt group’. All responses were read by the first author multiple times to build familiarity with the text. Basic codes that provided an initial text summary were assigned to each data point. As the ideas expressed by men in both the ‘Ideation’ and ‘Attempt’ groups were similar, responses were not analysed separately but reviewed together. Basic codes were then organised into sub-themes that cluster groups of codes together into a higher-level summary of perceived shared meanings. These sub-themes were then organised within overarching candidate themes. This analysis stage is highly interpretative, driven by the author’s perception of the deeper level of meaning within the data.

The author team constantly reviewed and reconsidered codes and themes at regular consensus meetings. Disagreements or questions were resolved by returning to the data and reflecting on its meaning (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Once coding was complete and the themes extracted, a consensus meeting was held to review the final thematic framework. During this meeting, it was suggested that the thematic framework echoed dimensions of Michie et al. (2011) behaviour change wheel (BCW). The BCW is based on insights from 19 behaviour change frameworks and stresses the importance and interaction of 1. Capability – physical and psychological; 2. Opportunity – physical and social; and 3. Motivation – reflective and automatic processes, in changing behaviours. To effectively increase male help-seeking, scholars have suggested that interventions be developed based on a theoretical understanding of behavior change processes (Sagar-Ouriaghli et al., 2019). We wanted our work to be of maximum pragmatic utility and as such we subsequently reviewed our thematic framework against the BCW. We were able to map all the themes onto specific BCW components without losing any analytical integrity. We felt that reconceiving our framework to integrate components of the BCW would allow our findings to move beyond “merely a psychological enquiry” to “research that can actively inform the development and implementation of interventions” (Pokhrel et al., 2015, p.1). We believe this integration strengthens the practical applicability of our findings by emphasising the critical areas within the BCW where men are potentially experiencing barriers. Final agreement on the reworked thematic hierarchy and illustrative quotes were made at a consensus meeting with all authors.

Data presentation

Results are organized by candidate themes along with their respective sub-themes (See Fig. 2). Whilst themes are presented as separate domains many men reported barriers from multiple themes and the model outlined in Fig. 2 strives to represent this dynamic interaction. Supporting quotes from respondents are used to illustrate thematic interpretations. Quotes are presented verbatim and are not corrected for spelling or grammar. Reference is made to whether the participant had thoughts of suicide or had previously attempted suicide and, where available, the recency of their ideation/attempt, number of attempts (where applicable), their current age, and location.

Thematic analysis is a flexible methodology with researchers invited to amend core principles to meet their own practices and processes (Braun et al., 2022). The purpose of a thematic analysis is not to find the most prominent meanings within a data set, but to identify the salient ones as perceived by the author team. As such, thematic analysis methodology does not require the quantification of codes. However, a degree of quantification allowed us to ground our analysis in some measure of prevalence for interpreted patterns. For each sub-theme and candidate theme, therefore, a percentage is included. This represents the percentage of codes from our analysis that suggests evidence for this theme. However, we urge caution about the interpretation of these numbers. For example, while 15% of codes from our analysis were about the sub-theme ‘Negative Experiences Accessing Support’ this is not representative of the actual number of men who may have had negative encounters. Participants were not directly asked that question, so the number could be higher. All supporting codes for our analysis can be reviewed in the supplementary material (‘Coding Analysis’).

Results

From the analysis, 963 basic codes were generated, organized into four candidate themes:

-

1.

No Motivation: Support Does Not Help (43% of codes)

-

2.

No Opportunity: Support is Physically Inaccessible (27% of codes)

-

3.

Social Costs: Support is Socially Stigmatized (16% of codes)

-

4.

Capability Constraints: Support is Psychologically Out of Reach (14% of codes).

We present the candidate- and sub-themes as discrete domains. Still, it is important to note that 26% of participants expressed concerns about more than one of the four candidate themes. See Table 2 for illustrative quotes of interacting barriers. These multiple and interacting barriers across the four candidate themes, may reinforce and strengthen obstacles to accessing professional support (see Fig. 2). Table 3 provides a breakdown of most endorsed sub-themes by recency of suicidal behaviors, age, and location.

No motivation: support does not help

Approximately 43% of codes described men whose motivation to seek support appeared severely compromised by the belief that professional support would not be helpful. This candidate theme is broken down into six sub-themes.

Negative experiences accessing support

In this sub-theme, the motivation of men to seek support was significantly undermined by past negative experiences with professional services. In the sample, approximately 15% of men reported such encounters, making negative experiences the second most prevalent sub-theme in the study. Participant responses revealed a range of negative encounters. Most men appeared to find previous help to be pointless, unhelpful, and ineffective. For a smaller group, therapy offered temporary relief, but was not beneficial over the long term. Other men suggested that the support they received amplified their feelings of suicide. Negative experiences were primarily related to doctors, therapists, and mental health professionals, although helplines and free services were also mentioned. The nature of negative encounters varied in description. Some men mentioned unpleasant experiences with therapy or medication; stigmatizing, or incompetent staff; perceived anti-male attitudes and of feeling unheard or diminished; long waiting times, only being offered medication, and/or men being sectioned against their will. Some participants explicitly referenced seeking help multiple times and trying a mixture of therapeutic and medical interventions, all perceived as ineffective. These unhelpful experiences appeared to undermine men’s motivation to seek support again. Some men described a loss of faith that they could be helped and of effectively giving up, resigning themselves to their psychological reality.

“The 'barriers' are that it doesn't work. I have tried this nonsense in the past for the best part of a decade and none of it does anything for me. The problem is not with me, it is the so-called """support""" offered and how shit it is.” (Ideation past week, 27, UK)

“(...) all the therapists I talked to in the past told me to "men up", "grow some", downplayed my issues ("That can't be a problem for such a big boy!") or made fun of me. I consider the profession of psychotherapy to be broken.” (Ideation past week, Attempt longer ago, 2 to 4 attempts, 40, Austria)

Negative perceptions of support as futile

Within the sample, 11% of men, from all income regions, and age groups, expressed sceptical beliefs about the utility of professional support. Unlike men in the previous sub-theme, this group did not explicitly reference negative past experiences but shared similar doubts about the effectiveness of available support. The reasons for their scepticism varied. Some men were suspicious of medication, doubting its effectiveness in addressing their issues. Other men didn't understand how talking about their problems could be beneficial, especially if they believed their struggles were caused by external factors like financial challenges or unchangeable biological realities, such as their perceived unattractiveness. A minority of men felt their pain was a valid response to the bleak conditions of existence and the world's brutality. Other men appeared to believe that they were beyond help and that their problems were too deep-seated or unsolvable.

“(...) In my case, you can take all the pills you want, talk for as long as you want, but ultimately, it's all a pointless exercise that doesn't alleviate the financial yoke constantly tied to your neck. It's band-aid on a gunshot would.” (Ideation past week, 51, UK)

“Therapy doesn't undo abuse and make you look attractive. Complete waste of time, money and effort” (Ideation past week, Attempt longer ago, 2 to 4 attempts, 19, Australia)

“Some things just can’t be unlearned. Realizing humanity is barelling towards collapse and our leaders would rather fuck each other over than even attempt anything past meaningless platitudes and encouraging literal fascism. Realizing my own and everyone else's lives come at the cost of blood, past and future, man and animal. Knowing that, help just comes off as wishful, blind optimism where none is warranted. I simply dont see the point.” (Ideation past week, Attempt longer ago, 2 to 4 attempts, 20, Pakistan)

Seeking help will undermine autonomy, agency, and control

Men in this sub-theme lacked motivation to access support as they appeared to believe that doing so could impact their autonomy, agency, and control (7%). These fears related to being sectioned, forced onto medication, and/or a permanent mark placed on their health records that could impact future job opportunities.

“In Croatia, if you visit a psychiatrist using the states funds- it is permanently marked on some sort of record so future employment companies can see that you've had psychiatric treatment, which would lead to 95% of them refusing to employ you. (...)” (Ideation past week, 21, Croatia)

“Having my agency removed from me and being placed in an institution (...)” (Ideation past week, Attempt past year, 1 attempt, 31, UK)

Mistrust of professionals

Within the sample, 6% of men, spanning all age groups and locations, expressed doubts about the integrity, skills, and attitudes of mental health professionals. These doubts appeared to undermine some men’s motivation to seek support. Some men raised questions about the motives of professionals, suggesting they were only interested in money and paid to care. Other men expressed concerns that professionals might struggle to comprehend or relate to their lived experiences, lack empathy toward the challenges faced by men, and/or only be interested in promoting medical interventions.

“(…) I feel like doctors don't really care about me or any other person, they just act caring for money or just because their profession requires so (…)” (Ideation past year, 19, USA)

“I have worked in health care for more than 30 years, and have personal knowledge of the attitudes of many HCW [Health Care Workers] to men and boys. I've experienced substantial overt misandry in many HCW, mental health providers, and particularly counsellors. [...] Why, when I need help and am at my most vulnerable, would I expose myself to such a demoralising experience.” (Ideation past week, Attempt longer ago, 2 to 4 attempts, 64, Australia)

Preference for self-reliance and self-management

A minority of men, across all age groups and locations, appeared to lack motivation to seek support because they believed they could handle their mental health challenges independently (3%). Dealing with problems alone was described as cathartic or a statement of strength.

“As stubborn as it may be, I prefer to deal with my emotions on my own and find it cathartic to work through them.” (Ideation past year, 21, UK)

“I don’t want anyone’s help. If I can’t get through my problems on my own, I’m not worth anything (…)” (Ideation past year, Attempt past year, 1 attempt, 27, USA)

Desire for death

A small minority of men (2%) expressed no motivation to seek professional support because they did not want to get better and/or wanted to die. Suicide rather than professional support appeared to be understood as the solution to their problems.

“I don't think that suicide is wrong. I just don't see the meaning in continuing with life, I don't see why should I live. And I don't understand why it should be so bad wanting to die when we live in a f-ed up world.” (Ideation past week, 18, Czech Republic)

“When im at the point of attempt or close to i dont want to be stopped so why would i contact anybody?” (Ideation past year, Attempt past year, 2 to 4 attempts, 59, UK)

No opportunity: support is physically inaccessible

From the data, 27% of codes related to men who described a lack of physical opportunity to access support, broken down into 2 sub-themes. This candidate theme highlights men who may be open to professional support but experience physical barriers in accessing it. As such professional support is understood to be out of reach.

Prohibitive costs

The most cited barriers were financial (20%). Prohibitive costs meant one-fifth of the sample experienced professional support as unaffordable. This was the most endorsed sub-theme in the study.

“I know how bad the NHS waiting lists for therapy are My past therapy was private and I can't afford that right now. So I'll just muddle through and hope I make it” (Ideation past year, 46, UK)

“In my country, this kind of help is hard to get, a good one even harder, and if you have no money, slashing your artery is a cheap and effective solution” (Ideation past week, Attempt longer ago, 1 attempt, 29, Brazil)

Inaccessible services

Seven per cent of the sample referenced practical barriers relating to the physical inaccessibility of services. Long waiting lists, a lack of services in their area, and/or professional support incompatible with work times were all mentioned. A few men expressed confusion around how to begin seeking professional support such as not knowing how to access it, who to call, not understanding the different pathways/therapeutic modalities, and whether services would be confidential.

“There are no mental health providers in my insurance in my area that take appointments outside of working hours. I would have to quit my job to see them, but then would lose my insurance so I wouldn't be able to anyway.” (Ideation past year, 26, USA)

“I don't know where to go or who to talk to (...)”. (Ideation past week, Attempt longer ago, 2 to 4 attempts, 18, Canada)

Social costs: support is socially stigmatized

Sixteen per cent of codes related to a lack of perceived social opportunity and cultural permission to access professional support, broken down into three sub-themes. This candidate theme describes men who appeared to inhabit social environments where they did not experience sufficient acceptability around help-seeking as a socially appropriate behaviour.

Harm to social value and relationships

Men in this sub-theme seemed to fear the potential harm to their reputation and social standing if other people found out they had sought help (8%). Men described concerns about other people’s reactions, fear of judgement, and how it could change how other people perceived and valued them and/or impact future romantic relationships. A cluster of men articulated concerns about harmful repercussions for family relationships. Some men seemed to fear that family members may be disappointed, embarrassed or think less of them. For some men, part of their pain related to family dynamics, and they were reluctant to confront these issues and make them known.

“Cultural norms "brown people dont go to therapy"” (Ideation past year, 18, Singapore)

“(...) I may be ridiculed by my extended family because most of them have regressive attitudes towards mental health issues, despite suffering from several themselves.” (Ideation past year, 18, India)

“(…) this would signal to my family that there is something wrong, and would open a can of worms I don't want to deal with (…)” (Ideation past week, Attempt longer ago, 1 attempt, 26, Latvia)

Seeking help is shameful

A smaller minority of men (5%) described their own shame and embarrassment as a barrier to accessing help. Men in this sub-theme appeared to believe that admitting “weakness” would mean dishonouring themselves by failing to live up to social expectations to cope alone and “get over” challenges. While some men seemed to endorse this idea, other men rejected it yet still, found themselves beholden to it.

“The admission of weakness (although my logical side understands just how stupid that is, pride gets in the way)” (Ideation past week, Attempt longer ago, 1 attempt, 33, Canada)

“Too taboo to talk about that as a man. (…) Just doing this survey makes me feel weak an is emasculating even though I strongly sympathise with men who are depressed. I would encourage men to go to therapy or get any other help because I would never judge them for that but I could never go myself.” (Ideation past week, Attempt longer ago, 2 to 4 attempts, 19, Australia)

Seeking support would impose problems on others

A minority of men (3%), all from high-income countries, and across all age groups, articulated a conceptualization of seeking support as causing harm to others, either by burdening them with their problems, causing loved ones to worry, or occupying space in already strained health systems that might be better utilized by someone else in greater need.

“(...) I don't want anyone to worry about me (...)” (Ideation past week, Attempt past year, 5 or more attempts, 23, USA)

“taking up resources that should be used on people more worthy or 'needy’” (Ideation past week, Attempt past year, 1 attempt, 51, Australia)

Capability constraints: support is psychologically out of reach

Fourteen per cent of codes related to men who perceived themselves to lack the psychological capability to access and/or utilize professional support broken down into two sub-themes. Accessing and making use of professional support was understood to require psychological tools and resources that some men seemed to believe were beyond their reach—as such support felt psychologically inaccessible.

Poverty of emotional language and expression

In the data, 7% of men described discomfort, fear, embarrassment, shame, resistance, and/or challenges around expressing their feelings. Men described not knowing how to share feelings and open up in general or specifically to a stranger/professional. Some men seemed to worry that they would be unable to express and communicate their problems effectively and that they could be misunderstood. Another small cluster of men described concerns that they may be unable to cope with confronting the reality of their emotional pain and that it may overwhelm them.

“(...) I don't know how to put my issues into words. I always feel ridiculous when trying to phrase it, it always appears shallow and misses the mark by miles (...)” (Ideation past week, 29, Germany)

“I don't like talking and it makes the pain so much worse so i rather bottle it up since that makes me feel a bit better” (Ideation past week, Attempt longer ago, 5 or more attempts, 20, Sweden)

Poverty of trust, self-esteem, and energy

For another cluster of men (7%) psychological barriers to accessing professional support related to a lack of confidence, low self-esteem, and feeling unworthy of help or attention; difficulties trusting others; insufficient energy to access help; and/or overwhelming social anxiety.

“I can barely brush my teeth, imagine spending 5 fucking hours trying to figure out if my insurance covers some asshole who's going to tell me to improve my diet and go for a walk (...)" (Ideation past week, 27, Canada)

“Extremely low trust in others” (Ideation past year, 24, UK)

“once again, i do not deserve my problems to be fixed. i believe i deserve to die.” (Ideation past week, Attempt past year, 2 to 4 attempts, 20, UK)

“(...) I have severe anxiety problems with going outdoors in public or to new places and I don't think I could manage it without engaging in extensive self harm to cope with the stress. (...)” (Ideation past week, Attempt longer ago, 1 attempt, 23, UK)

Discussion

Our analysis yielded four candidate themes: 1. No Motivation: Support Does Not Help (43% of codes); 2. No Opportunity: Support is Physically Inaccessible (27% of codes); 3. Social Costs: Support is Socially Stigmatised (16% of codes); and 4. Capability Constraints: Support is Psychologically Out of Reach (14% of codes). Many of these themes, drawn from a large sample of men who are currently or recently suicidal, align with similar barriers found in existing literature exploring help-seeking barriers among men with various mental health challenges and suicide-specific research that has employed smaller qualitative samples or quantitative and psychological autopsy methodologies (Hoy, 2012; Oliffe et al., 2020; Rasmussen et al., 2018). In this discussion, we explore the potential role of masculine norms in influencing help-seeking behaviors in men who are suicidal, and the need for gender-sensitive, culturally-sensitive interventions, tailored to different age groups. We discuss how the barriers we have identified, specific to men who are suicidal, align with the domains of Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation from Michie et al.’s (2011) behavior change wheel (BCW). By mapping our findings onto an established theoretical framework for behavior change we hope to help colleagues develop more effective and targeted interventions to enhance the help-seeking behaviors of men who are suicidal. Additionally, by placing our findings in the context of previous research into the psychology of men who are suicidal, we hope to illuminate why some of these barriers are particularly relevant and concerning for a male suicide population. Our evidence suggests male help-seeking barriers must be considered in relation to the help available and whether it is accessible, appropriate, and wanted by men who are suicidal. We propose potential recommendations for interventions, services, and public health campaigns throughout the discussion, and these are summarized in Table 3.

Masculine norms and male help-seeking

In our data, cultural norms of masculinity appeared to underpin some of the barriers men who are suicidal experience in their capability, opportunity, and motivation to access professional support. A poverty of psychological capability may partly be rooted in the cultural suppression of men’s emotions. Social opportunities to access help may be restricted by cultural expectations for men to be strong, deny pain, and protect others. Men’s motivation to access help may be affected by masculine norms of self-reliance, independence, control, and autonomy, which may lead some men to prefer to self-manage their challenges and mistrust professionals. Concerns about being medicated, hospitalized, or help-seeking negatively affecting future job and romantic opportunities, may loom large for men conditioned to be in control and successful. Talking therapy premised on articulating and exploring emotional challenges may not make sense to some men conditioned to deny their feelings. Consequently, our findings support previous recommendations for developing gender-sensitive male suicide prevention interventions that “move beyond simplistic ideas about pathological masculinities” and engage with the multiple ways in which masculinities may interact to shape men’s help-seeking (p. 2, Oliffe et al., 2020; Galdas et al., 2023). There are complicated intricacies to balance in developing male-sensitive interventions. Developing male-friendly services is not to treat men as a homogenized entity. Masculinity does not refer to fixed traits inherent to all men but to social and cultural expectations for male behaviour and these expectations will vary significantly across different social contexts, and different stages of a man’s life (Connell & Messerschmidt, 2005). Every man is an individual shaped by distinct biological, socioeconomic, political, environmental, and structural factors (Turecki et al., 2019). As such, masculinities are plural, and men are a diverse population, with intersecting identities (Coston & Kimmel, 2012; Seidler et al., 2018). What is true for one man, i.e., the belief that getting help is weak, is not true for other men who may want support but cannot access it. Similarly, different interventions are required to both meet men in their immediate cultural conditions, i.e., develop services that support men to be self-reliant, whilst also seeking long-term cultural change, i.e., normalizing men as interdependent, relational beings who do not need to have to cope alone (Galdas et al., 2023; Sagar-Ouriaghli et al., 2019; Seidler et al., 2019). Additionally, interventions may need to work positively with masculinity to celebrate masculine strengths, while also challenging what might need to change (Galdas et al., 2023; Seidler et al., 2018), and balance helping men accept having mental health challenges without aggravating feelings of shame, failure, or loss of control (Sagar-Ouriaghli et al., 2019).

Our sample was too small to draw direct cultural comparisons. Nonetheless, across all cultural locations, prohibitive costs were the most endorsed theme, with negative past experiences also prevalent for men in upper-income, and upper-middle-income countries. For lower-middle-income countries, sceptical beliefs about the utility of support and potential social stigma were particularly prevalent (see Table 3). Negative past experiences were the most endorsed theme for men aged 31–50 and men 50 + . For younger men aged 18–30 it was prohibitive costs. These variations in barriers among men in different cultural locations and age groups suggest targeted and tailored interventions may be required but will require further research to scope out properly. Across all cultural settings and age brackets, men in our data experienced barriers to accessing help concerning their capability, opportunity, and motivation. In the remaining discussion, we will explore potential interventions to begin to tackle these.

‘Motivation’ interventions

Our findings predominantly related to a lack of motivation in men who are suicidal to seek professional help. Of significant concern are the 15% of men who cited negative past experiences – the second most endorsed theme in this study. This finding resonates with previous research that some men who are suicidal are going for help but have bad experiences with a lack of services (Chandler, 2021), a lack of time for proper assessment (Strike et al., 2006), and an over-reliance on medical solutions (Oliffe et al., 2020; River, 2018) previously cited. This evidence suggests that professionals and public health messaging should avoid one-dimensional characterizations and understandings of men as poor/reluctant help-seekers, which may distress the many men who are suicidal who have accessed help and had negative encounters or the many men—as seen in our data—who appear to want help but are unable to access it because of prohibitive costs or a lack of available services.

The accumulating evidence that some men who are suicidal find professional interventions ineffective, unhelpful and, at worst, damaging presents a fundamental problem for male suicide prevention. The effectiveness of encouraging male help-seeking as a suicide prevention strategy depends on available support being helpful (Seidler et al., 2018). Evidence suggests interventions like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) help reduce suicidal behaviors but they are not always available (Bryan, 2022) and it is not clear that they work for men (O’Connor et al., 2023). Going for help and having a negative experience may compound feelings of hopelessness and entrapment in men who are suicidal, potentially strengthening their perception of suicide as the only resolution to their pain. For example, some men in our study stated that they didn’t want to access help because if they did and the help ‘failed’, they would have no option but to end their lives. As such, not seeking support was potentially, and paradoxically, helping to keep these men alive. This presents an ethical dilemma for the suicide prevention community. Public health campaigns may need to consider the delicate task of communicating the complex reality of seeking professional help within the current resources of many mental health systems. Is it better to prepare men for the reality that seeking support may be slow, ineffective at times, but potentially lifesaving rather than suggesting it is a simple and quick process that can reduce suicide risk instantly? Additionally, as a matter of urgency, we need to identify why professional support is not working for some men who are suicidal, including conducting further research to understand their specific needs; what type of support they want and how best to deliver this (Ashfeld & Gouws, 2019; Bilsker & White, 2011; Kingerlee et al., 2019; Mahalik et al., 2012; Oliffe et al., 2020; Seidler et al., 2018; Wenger, 2011). Scholars have suggested that effective interventions for male mental health in general may need to consider how to honour some men's desire for autonomy and control, to be self-reliant and/or to manage pain privately (Hoy, 2012); using role models to share information and building on positive male traits like responsibility and strength (Sagar-Ouriaghli et al., 2019); and psychological treatments that are person-centered and collaborative (Seidler et al., 2018). Galdas et al. (2023) have developed a 5 ‘C’ framework of co-production, cost, context, content, and communication to guide the development of masculinity in men’s health (Galdas et al., 2023). Building on these findings, we now need to understand what works specifically for men who are suicidal.

Part of this work will be about understanding how men understand the causes of their suicidal pain. Consistent with other findings, men in our data had reservations about the efficacy of medication and/or talking therapies and questioned the utility of support that did not address structural challenges, like unemployment/debt, or relationship challenges (Mallon et al., 2019; Hoy, 2012; Rasmussen et al., 2018; River, 2018). A recent review of priority actions to prevent suicide stresses the value of multimodal interventions (O’Connor et al., 2023). Our findings support this position and suggest that strengthening links between mental health services and interventions that tackle structural challenges (such as unemployment, addiction, or debt) could be important for men who are suicidal. It may also be useful to make the case to men that while strengthening emotional regulation through therapy cannot necessarily alleviate structural challenges, it may support men in navigating these challenges more effectively.

Other men in our data, seemed to understand their suicidal pain to be a legitimate response to existence's perceived brutality and meaninglessness. Rather than medical intervention, these men may be looking for moral guidance and/or existential community. Consequently, male suicide prevention may need to situate professional support as one component within a network of potential help-seeking options that reflect how different men make sense of their suicidal pain. In coping with a suicidal crisis men may draw on help from significant others, community/peer/work support, literature, music, sport, nature, solitude, self-management tools, and others (Biong & Ravndal, 2007; Ferlatte et al., 2019). Some men may want non-medical, non-therapeutic interventions, that are more about building community bonds, interpersonal relationships, moral comfort and/or guidance to help discover meaning and purpose. Research in Ghana suggests instead of clinical professionals, religious leaders may be well positioned to provide counselling to persons in suicidal distress (Osafo et al., 2015). Given the strain on some mental health systems and the financial barriers of private support, investing in community, work, and peer support interventions as additional and/or alternative help-seeking routes for men who are suicidal may be a way to provide more immediate and acceptable forms of intervention and care for some men. Evidence suggests all these non-medical interventions have utility for some men for who are suicidal (Bennett et al., 2023a, b; Roche et al., 2016; Struszczyk et al., 2019). Self-disclosure in these environments can reduce stress, stigma, shame, normalize feelings, build self-acceptance, self-worth, and intimacy with others (Di Bianca & Mahalik, 2022; Ferlatte et al., 2019; Ross et al., 2019). Addis and Mahalik (2003) suggest men are more likely to seek help if they can reciprocate, which may be an additional reason community and peer lead interventions are appealing for some men.

Masculine norms may also impact how professionals understand and respond to men’s pain. Scholars have suggested that some professionals may lack compassion for the male experience, undermining men’s confidence, and motivation to seek support (Liddon et al., 2019). Mistrust of professionals was a theme in our data, as well as past experiences of professionals perceived as lacking compassion for the male experience. Whilst we seek to encourage men to talk, we must also consider who is listening and whether they are competent to hear men’s pain. Our findings support recommendations from scholars for: 1. gender-sensitive assessment and treatment plans in clinical practice; 2. modules on male socialization and masculine norms in health-professional training programmes; and 3. tools to help professionals address their own gender bias (Mahalik et al., 2012; Seidler et al., 2019). 'Man Talk,' an intervention to increase the understanding of Samaritan volunteers of the male experience, reduced the number of short calls with men (Liddon et al., 2019). Data from our study also suggest professionals may benefit from a deeper understanding of how some men who are suicidal perceive professionals. The view some men who are suicidal hold of professionals as financially privileged, motivated by money, hostile towards men, and protected from the kinds of suffering they have endured, may impact help-seeker/help-giver dynamics. Further investigation of these views and interventions to improve professional training and compassionate ways of working with men may be useful.

‘Opportunity’ interventions

The second component of behaviour change relates to the ‘opportunity’ in a person's physical and/or social environment to undertake a behaviour (Michie et al., 2011). In our data, we found evidence of barriers in both domains. Some men spoke of a lack of physical opportunities to access services with 27% of codes relating to prohibitive financial costs, long waiting lists, lack of service availability and time constraints, particularly when support was only available during working hours. Long waiting lists have been previously documented in the UK mental health system (Reichert & Jacobs, 2018; Punton et al., 2022). The lack of physical opportunities to access help may be particularly concerning when considering the state of mind of men who are suicidal. Feelings of hopelessness, defeat, and entrapment are theoretically implicated as drivers of suicidal despair (O’Connor & Kirtley, 2018). Knowing that private support is financially out of reach and that state mental health systems are under pressure, with limited services and long waiting lists, could compound a sense of hopelessness and entrapment for some men. A recent Delphi study to set priorities for male suicide research highlighted the urgent need to develop interventions for men who cannot afford therapy (Bennett et al., 2023a, b). Findings here support the potential significance of this work. Digital psychoeducation programmes and tools for managing suicidal behaviours may be a low-cost solution. Digital interventions could allow men to access support immediately, within their own environments, and timeframes. Digital interventions have been identified as safe and non-confrontational tools for engaging men, particularly those who endorse masculine norms of self-reliance (Gilgoff et al., 2023; King et al., 2019). An evaluation of an Australian male suicide website featuring videos, psychoeducation materials, and profiles of male celebrities, showed it helped support help-seeking activities (King et al., 2019). Similarly, an evaluation of ‘Man Therapy’ an American online suicide prevention website found a statistically significant association between the website and professional help-seeking (Gilgoff et al., 2023). The success of these digital interventions in strengthening help-seeking behaviors suggests digital interventions are a medium some men engage with, and worth testing broader interventions through. As well as low-cost, digital interventions may be helpful for men experiencing social anxiety, men who mistrust professionals, men who want to self-manage a suicidal crisis, and men who want to avoid social stigma by accessing help privately and anonymously.

A lack of social opportunity was also referenced in our data. Primarily men described the stigma of others as a barrier. Participants in this study represent 57 countries and, in many locations, and communities, mental health stigma may be oppressively prevalent. Suicide prevention campaigns cannot assume that it is socially safe for all men in all environments to admit their struggles and there may be real costs for some men of disclosing their distress (Chandler, 2021). Continued population-level public-health campaigns to change social attitudes around male help-seeking may be important and these campaigns should not only target male behaviours. Men are embedded in social networks, and the attitudes of the people around men will influence their own (Di Bianca & Mahalik, 2022). Family, community, friends, and workplaces need to normalize help-seeking and reduce social costs for men of accessing support. High-profile men and prominent cultural/community role models speaking about their mental health may also be important to help normalize help-seeking.

A small minority of men spoke of their own shame as a barrier to getting help and this accords with research that suggests social expectations for men to be strong, stoic, and suppress emotional suffering may make some men reluctant to seek help (Addis & Mahalik, 2003; Keohane & Richardson, 2018). The small endorsement of this theme (5%) suggests the social climate around normalizing male distress and help-seeking may be gradually shifting though there is still work to do. Some men rejected expectations that getting help was weak and yet suggested they could not bring themselves to get support. While campaigns to normalize help-seeking in men have increased (Sagar-Ouriaghli et al., 2019), health professionals should be sensitive to a potential ‘cultural lag’ as entrenched norms are uprooted. New norms are not instantly adopted. Some men may be caught in the crossfire of the dissonance between old norms around ‘male emotional suppression’ and new cultural expectations for ‘men to talk’. Residual cultural shame around getting help, and being emotionally vulnerable, suggests public health messaging, may need to work to place the centrality of emotions back in men's psyches. Like all humans, men are affective beings whose affective systems have evolved over millions of years (Damasio, 2018; Ozawa-de Silva, 2021; Langs, 1996). Understanding, processing, and managing our emotions is critical to our well-being (Barrett, 2017). Encouraging men to understand their emotional distress is not to encourage more ‘feminine’ behaviour but to help men reclaim a fundamental aspect of human regulation culturally denied to many. Scholars have also warned caution about the current framing of masculinity in public discourse as "toxic" which may contribute to some men perceiving social hostility towards their experiences (Ashfeld & Gouws, 2019; Seager, 2019). This may make sharing vulnerabilities—an already potentially dangerous endeavour because of transgressing masculine norms—feel even more unsafe. Similarly, the characterization of men as the privileged sex/gender may amplify shame and failure for men struggling to cope. Increasing men’s uptake of professional support may require a more nuanced and compassionate public dialogue about the reality of the male experience in contemporary societies and how cultures may be harmful and oppressive for men (Bennett et al., 2023a, b; Lee et al., 2002).

Our findings also suggest that for men in upper-income contexts, fears of transgressing social norms of male protection may also be a barrier to men seeking support. Masculine norms that suggest men must protect others may mean some men struggle to conceive of themselves as legitimate candidates and recipients of care and concern (Seager, 2019). Our study supports previous assertions that for many people, help-seeking is an ongoing dialogue between potential harms and benefits (Addis & Mahalik, 2003; Keohane & Richardson, 2018). Wenger (2011) notes that with cancer or sexual dysfunction, men can be willing to risk help-seeking because of the perceived benefits "of survival or preserved sexual performance" (p. 6). There may be important lessons here for the suicide prevention community to re-frame help-seeking in terms that resonate with current masculine identities and foreground what a man may gain by seeking support (Farrell et al., 2016). Co-production with men who have accessed support and benefited from it could help to develop effective messages. For example, framing help-seeking as taking control of a crisis, and/or as an act of love, protection, provision, and care for loved ones who will ultimately benefit from a man feeling better and staying alive, could be effective messaging (O’Donnell & Richardson, 2018). Public health messaging could also consider how to position men as individuals deserving of support.

‘Capability’ interventions

According to Michie et al.'s (2011) BCW model, ‘capability’ is central to behaviour change—people will only attempt a behavior if they believe they can do it. Our findings suggest that some men who are suicidal feel they lack the psychological capability to access and utilize professional support. Consequently, help may seem psychologically out of reach. Men in our study expressed concerns about their ability to describe their emotions or discomfort around talking about feelings. This accords with previous evidence that suggests that men who are suicidal can experience emotional suppression, disconnection, and dysregulation (Bennett et al., 2023a, b). Feeling unable to articulate emotional pain may make seeking help distressingly inaccessible – some men may wonder how they can be helped for something they cannot describe. Other men described a lack of self-esteem as a psychological barrier and appeared to feel unworthy of help. This also aligns with existing evidence that suggests men who are suicidal can experience profound feelings of low self-worth and failure (Cleary, 2017; Coleman et al., 2011; Oliffe et al., 2017). Consequently, some men may believe themselves undeserving of support. Other men described a lack of trust as a psychological barrier. Again, mistrust, isolation, and interpersonal dysregulation, have all been reported in male suicide crises (Di Bianca & Mahalik, 2022; Meissner & Bantjes, 2017; Möller-Leimkühler, 2003). Professional help-seeking dynamics premised on trusting a stranger with intimate pain and vulnerability may feel psychologically out of reach for some men who are suicidal. Other men suggested they were too ‘anxious’, too ‘depressed’, and/or lacked the energy to access support and commit to an intervention. This also accords with existing evidence that suggests men in acute suicidal pain can experience profound exhaustion, anxiety, low mood, and impaired cognitive functioning (Benson et al., 2016; Salway & Gesink, 2018). As such, men in heightened suicidal distress may feel they lack the cognitive and emotional resources to organize help and commit to it.

Taken together, this evidence underscores the potential importance of developing interventions that: 1. help men who are suicidal build their psychological capabilities; and 2. are designed based on a deep understanding of the psychology underpinning a male suicide crisis. Sagar-Ouriaghli et al. (2019) systematic review of male-specific interventions to improve men’s mental health help-seeking, identified psychoeducational tools—that improve men’s psychological literacy and capacity to identify and regulate symptoms—as helpful. Our data suggest these interventions may be valuably tested in male-suicide-specific populations, for whom a perceived inability to access help, may strengthen the perception of suicide as the only viable route out of pain.

Public health campaigns could also challenge men’s assumptions that they lack the emotional capability to access support. Humans are sentient, emotional beings (Barrett, 2017; Ozawa-de Silva, 2021). While some men may not feel proficient in articulating the language of their emotions, they are the experience holders of them. Articulating and regulating feelings is a learnable skill that, with support, can be built further (van der Kolk, 2014). An individual man is an expert in their life and history, which is the raw material of a therapeutic intervention. Messages that problematize how men are socialized could help frame a perceived psychological incapability as a consequence of the cultural suppression of men's emotions rather than as symbolic of personal failure or inadequacy (Ashfeld & Gouws, 2019; Liddon et al., 2019). Similarly, it may be important that public health campaigns do not portray men as emotionally impaired, underdeveloped, or limited, as this characterization may cause some men to further internalize a sense of being psychologically incapable (Seager, 2019).

Theoretical and practical implications

Male suicide rates are alarmingly high and underscore the urgency of this study, which, to the authors' knowledge, is one of the largest investigations into the barriers men who have been suicidal in the past week or year, experience in seeking professional help. Our findings present important evidence concerning the challenges that potentially prevent men who are suicidal from accessing the professional support they may critically need.

Our findings echo existing theoretical evidence for how masculine norms may inform men’s help-seeking behaviours, the need for gender-sensitive services, and the importance of moving beyond a shallow understanding of men as poor help-seekers (Hoy, 2012; Oliffe et al., 2020). Masculine norms manifest differently in individual men, across diverse cultural contexts, and age groups. Suicide prevention must be cautious to develop gender-sensitive services that recognize the individuality of each man. Furthermore, it is crucial to explore how norms and expectations for male behaviour impact responses to male pain from mental health professionals, and the people and communities around men in crisis.

Given the gravity of suicide, tackling the barriers some men face is urgent. Theories of suicide suggest hopelessness and entrapment are critical components of a suicidal crisis (O’Connor & Kirtley, 2018). Help that is perceived to be inaccessible, unavailable, or unhelpful in meeting some men’s needs, may compound some men’s suicidal despair. Evidence also suggests men who are suicidal may experience emotional dysregulation, exhaustion, impaired cognitive functioning, feelings of failure, low self-esteem, low trust in others, and isolation (Bennett et al., 2023a, b). This psychological context will constrict some men’s capability to access and engage with support and must be considered when designing services. Our findings suggest the importance of developing interventions that consult lived experience experts to minimise potential harm and maximize effectiveness.

From a practical standpoint, our findings provide recommendations for interventions to improve male help-seeking outlined in Table 4. Our findings align with the principles of Michie et al.'s (2011) behaviour change framework, emphasizing challenges in men’s capability, opportunity, and motivation towards getting help. As an urgent priority, we need to strengthen men’s motivation to get help, by problematizing the support available and exploring how it can be made acceptable and accessible for more men. We support positions for a multifaceted suicide prevention approach that includes psychological and structural support for men, training for professionals to deliver gender-sensitive compassionate care for men, and expanding help-seeking opportunities to include community, work, and peer-led support. We need to strengthen men’s physical opportunities to access help, including exploring low-cost, scalable digital interventions, and social opportunities via public health campaigns that normalize male distress and male help-seeking. Men’s psychological capability to get help could be strengthened via psychoeducation tools to support the psychological literacy and coping tools of men and boys. The practical implications of our findings extend to policy changes, namely funding for the work outlined in Table 4, support for the development of gender-sensitive suicide prevention policies and programmes that consider the diverse needs of men, and policies that help foster a culture of compassion towards male distress and social acceptance and legitimacy for their struggles.

Limitations

Like other qualitative research, the findings from this study are not generalizable and are subject to the subjective interpretations of the author team. A different group of analysts may have developed and prioritized alternative interpretations. Our sample was mainly drawn from high-income contexts, and critical factors such as race, culture, religion, and sexuality can moderate help-seeking behaviours and are not addressed directly here (Luoma et al., 2002; Nam et al., 2010). Although suicide deaths did not increase during the pandemic (Pirkis et al., 2021), data were collected during the Covid-19 pandemic, and we cannot fully account for its influence on participants' responses. Additionally, the study is based on participants' self-reported barriers towards seeking help. Consequently, responses may be influenced by subjective biases such as perceptions that help is unavailable when it is, but the participant did not identify the help. In addition, participants may have given answers that they felt were socially desirable, leading to an underrepresentation of less socially acceptable views. Our analysis was based on open-text responses to a survey question. This methodological approach helped us to reach and collect data from hundreds of men in different cultural locations. However, it is likely to have limited the depth of meaning that may be possible when using other methods. Unlike more immersive qualitative methods, such as interviews, our data does not allow for a contextualised exploration of participants' perspectives and barriers towards seeking support. Similarly, our sample was cross-sectional and as such, we were unable to explore the temporal relationship between help-seeking attitudes and suicidal behaviors. While our analysis offers valuable and unique insights, like all methodologies, its findings need to be interpreted in the context of its limitations.

Conclusion

Help-seeking is a “complex decision-making process” (Cornally & Mccarthy, 2011, p. 286), and this is reflected in our findings which suggest that men who are suicidal experience multiple barriers that impact upon their professional help-seeking behaviors. Findings from our study support the broader evidence from male mental health research that incorporating a gender-sensitive approach into strategies for men’s health is vital (Bennett et al., 2023a, b; Galdas et al., 2023; Seidler et al., 2018, 2019). This includes understanding how men make sense of their suicidal pain and what kind of help they want; recognizing the influence of gender norms on men's help-seeking behaviours and how professionals treat and respond to men in crisis; increasing men’s psychological capability to access support; integrating an understanding of masculine norms and male socialization into professional training; creating gender-sensitive services – from the language and branding used, to the environments in which interventions are delivered – that are multi-modal and tackle both psychological and structural stressors; and integrate professional support alongside potential community, peer, and work interventions to increase physical and social opportunities for men to access effective support (Mahalik et al., 2012; Seidler et al., 2018, 2019). Our study suggests that simplistic presentations of men as reluctant help-seekers undermine a complex reality and will not move us forward in developing appropriate, accessible, and appealing interventions for men. By reviewing help-seeing barriers across a large sample of men who are currently or recently suicidal and mapping these barriers onto the theoretical framework of Michie et al.’s (2011) behavior change wheel (BCW), we hope our findings can contribute to a richer, theoretical understanding from which more effective interventions can be developed. We make 23 recommendations to support this important endeavour.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article (and its supplementary information files).

References

Addis, M. E., & Mahalik, J. R. (2003). Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. American Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.5

Ashfeld, J. A., & Gouws, D. S. (2019). Dignifying Psychotherapy with Men: Developing Empathic and Evidence-Based Approaches That Suit the Real Needs of the Male Gender. In J. A.Barry, R. Kingerlee, M. Seager, & L. Sullivan (Eds.),The Palgrave handbook of male psychology and mental health. Cham, Switzerland : Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04384-1_27

Barrett, L. F. (2017). How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. Houghton Miffli.

Bennett, S., Robb, K. A., Zortea, T. C., Dickson, A., Richardson, C., & O’Connor, R. C. (2023a). Male suicide risk and recovery factors: A systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis of two decades of research. Psychological Bulletin, 149(7–8), 371–417. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000397

Bennett, S., Robb, K. A., Andoh-Arthur, J., Chandler, A., Cleary, A., King, K., Oliffe, J., Rice, S., Scourfield, J., Seager, M., Seidler, Z., Zortea, T. C., & O’Connor, R. C. (2023b). Establishing research priorities for investigating male suicide risk and recovery: A modified delphi study with lived-experience experts. psychology of men & masculinities. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000448

Benson, O., Gibson, S., Boden, Z. V. R., & Owen, G. (2016). Exhausted without trust and inherent worth: A model of the suicide process based on experiential accounts. Social Science and Medicine, 163, 126–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.06.045

Bilsker, D., & White, J. (2011). The silent epidemic of male suicide. British Columbia Medical Journal, 53(10), 529–534.

Biong, S., & Ravndal, E. (2007). Young men’s experiences of living with substance abuse and suicidal behaviour: Between death as an escape from pain and the hope of a life. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 2(4), 246–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482620701547008

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Hayfield, N. (2022). ‘A starting point for your journey, not a map’: Nikki Hayfield in conversation with Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke about thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 19(2), 424–445. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2019.1670765

Bryan, C. (2022). Rethinking Suicide: Why Prevention Fails, and How We Can Do Better. Oxford University Press.

Chandler, A. (2021). Masculinities and suicide: Unsettling ‘talk’ as a response to suicide in men. Critical Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2021.1908959

Cleary, A. (2017). Help-seeking patterns and attitudes to treatment amongst men who attempted suicide. Journal of Mental Health, 26(3), 220–224. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2016.1149800

Coleman, D., Kaplan, M. S., & Casey, J. T. (2011). The social nature of male suicide: A new analytic model. International Journal of Men’s Health. https://doi.org/10.3149/jmh.1003.240

Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity. Gender & Society, 19(6), 829–859.

Cornally, N., & Mccarthy, G. (2011). Help-seeking behaviour: A concept analysis. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 17(3), 280–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2011.01936.x

Coston, B., & Kimmel, M. (2012). Seeing privilege where it isn’t: Marginalized masculinities and the intersectionality of privilege. The Journal of Social Issues, 68(1), 97–111.

D'Anci, K. E., Uhl, S., Giradi, G., & Martin, C. (2019). Treatments for the prevention and management of suicide: A systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 171(5), 334–342. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-0869

Damasio, A. (2018). The strange order of things: Life, feeling, and the making of cultures. New York: Pantheon.

De Leo, D., Cerin, E., Spathonis, K., & Burgis, S. (2005). Lifetime risk of suicide ideation and attempts in an Australian community: Prevalence, suicidal process, and help-seeking behaviour. Journal of Affective Disorders, 86(2–3), 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2005.02.001

Di Bianca, M., & Mahalik, J. R. (2022). A relational-cultural framework for promoting healthy masculinities. The American Psychologist, 77(3), 321–332. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000929

Farrell, W., Seager, M., & Barry, J. (2016). The Male Gender Empathy Gap: Time for psychology to take action. New Male Studies, 5(2), 6–16. Retrieved from http://www.newmalestudies.com/OJS/index.php/nms/article/view/227. Accessed Aug 2022.

Ferlatte, O., Oliffe, J. L., Louie, D. R., Ridge, D., Broom, A., & Salway, T. (2019). Suicide prevention from the perspectives of gay, bisexual, and two-spirit men. Qualitative Health Research, 29(8), 1186–1198. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318816082

Fowler, K., Kaplan, M., Stone, D., Zhou, H., Stevens, M., & Simon, T. (2022). Suicide among males across the lifespan: An analysis of differences by known mental health status. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2022.02.021

Galdas, P. M., Cheater, F., & Marshall, P. (2005). Men and health help-seeking behaviour: Literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03331.x

Galdas, P. M., Seidler, Z. E., & Oliffe, J. L. (2023). Designing men’s health programs: The 5C framework. American Journal of Men’s Health, 17(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/15579883231186463

Gilgoff, J. N., Wagner, F., Frey, J. J., & Osteen, P. J. (2023). Help-seeking and man therapy: The impact of an online suicide intervention. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 53(1), 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12929

Hamdi, E., Price, S., Qassem, T., Amin, Y., & Jones, D. (2008). Suicides not in contact with mental health services: Risk indicators and determinants of referral. Journal of Mental Health, 17(4), 398–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230701506234

Hjelmeland, H. (2013). Suicide research and prevention: The importance of culture in “Biological Times”. In E. Colucci & D. Lester (Eds.), Suicide and culture: Understanding the context (pp. 3–24). Hogrefe Publishing.

Hoy, S. (2012). Beyond men behaving badly: A meta-ethnography of men’s perspectives on psychological distress and help seeking. International Journal of Men’s Health. https://doi.org/10.3149/jmh.1103.202

Keohane, A., & Richardson, N. (2018). Negotiating gender norms to support men in psychological distress. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(1), 160–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988317733093

Kiamanesh, P., Dieserud, G., & Haavind, H. (2015). From a cracking façade to a total escape: Maladaptive perfectionism and suicide. Death Studies, 39(5), 316–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2014.946625

King, K., Schlichthorst, M., Turnure, J., Phelps, A., Spittal, M. J., & Pirkis, J. (2019). Evaluating the effectiveness of a website about masculinity and suicide to prompt help-seeking. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 30(3), 381–389.

Kingerlee, R., Abotsie, G., Fisk, A., & Woodley, L. (2019). Reconnection: Designing Interventions and Services with Men in Mind. In Barry, J. A., Kingerlee, R., Seager, M., & Sullivan, L. (Eds.),The Palgrave handbook of male psychologyand mental health. Cham,Switzerland:SpringerInternationalPublishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04384-1_27

Kõlves, K., Kumpula, E.-K., & de Leo, D. (2013). Suicidal Behaviours in Men. Determinants and Prevention in Australia. Australian Institute for Suicide Research and Prevention.

Langs, R. (1996). The evolution of the emotion-processing mind: With an introduction to mental Darwinism. London: Karnac Books.

Lee, C., & Owens, R. G. (2002). Issues for a psychology of men’s health. Journal of Health Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105302007003215