Abstract

The Sexual Double Standard is a complex multi-layered construct that functions as an organizing principle of heterosexual behavior. It is a dynamic, ubiquitous, two-dimensional sexual gendered norm, the quantitative exploration of which requires up-to-date assessment tools to better capture both personal endorsement and social recognition of the SDS. This study develops a New SDS Scale to assess personal SDS, which is easily adapted to measure societal SDS, with demonstration of its validity and gender invariance. College students (N = 481) completed the New SDS Scale, plus convergent-divergent and concurrent validity measures. Exploratory analysis indicated an eight-item two-factor structure. Confirmatory factor analysis showed the better adjustment of a bifactor structure combining a general factor of SDS and the subscales Sexual Relationships and Actions/Activities. In addition to factorial validity, results were also demonstrative of convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity, and reliability and gender invariance were demonstrated. The new scale may be a useful tool to briefly assess personal endorsement of the SDS or of alternative standards, and it can easily be adapted to measure perceptions about the social existence of the SDS. Beyond the potential for practical application to individual or group assessment in clinical and educational settings, the New SDS Scale updates our knowledge on the types of sexual conduct that elicit the SDS, identifying critically gendered activities for which permissiveness continues to be markedly differentiated, despite the openness and sexual freedom of recent years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Sexual Double Standard (SDS) is an evaluative, gendered norm of sexual conduct that apportions more freedom to men and dictates, as a rule, more negative judgment and sanctioning of women engaging in the same type of sexual behavior. The SDS rewards men for active – even promiscuous – sexuality, considered the reflection of true masculinity, while women’s status or reputation depends on them controlling or minimizing sexual expression and experience, as chastity is seen as the true face of femininity (McCarthy & Bodnar, 2005). Thus, although it lacks a conceptual structure of its own (Zaikman & Marks, 2017), the SDS is firmly grounded in the sexual gender roles and stereotypes, i.e., the social shared beliefs about traits and behaviors that are appropriate, expected, or unacceptable for men and for women, and that can be described through the dichotomous idea of the active, sexual man vs. the passive, emotional woman (Amaro et al. 2021a; Eagly et al., 2004; Farvid, 2018; Fasula et al., 2014; Howard & Hollander, 1997). Recent review works have found that the SDS has weakened over the past several years, but have simultaneously shown that it continues to manifest itself frequently in the evaluation of particular forms of conduct, such as casual sex and having multiple sexual partners (e.g., Amaro et al., 2021b; Endendijk et al., 2020). The SDS has weakened and ceded ground to a Single Sexual Standard (SSS) that prescribes equality of freedom, judgement, and sanctioning, as well as to a Reversed Sexual Double Standard (reversed SDS) that prescribes less freedom, more negative judgment, and more severe punishment for men than for women. This is consistent with the ongoing process of sexual liberalization and of degenderization of (hetero)sexuality that has taken place over the last decades in Western societies (Amaro et al., 2021a; Bordini & Sperb, 2013; Crawford & Popp, 2003; Endendijk et al., 2020; Farvid, 2018). However, this same process of social transformation has led to a displacement in the content of the SDS (e.g., from premarital sex to casual sex), which helps to explain why the standard has persisted through time and is still a reality that is important to know and to combat if we want to promote gender equality as well as free, safe and satisfying (hetero)sexual experiences (Amaro et al., 2021b; Bordini & Sperb, 2013; Endendijk et al., 2020).

The SDS began as a definition of differential acceptance of sex before marriage (Reiss, 1956, 1960), but over time came to describe a general pattern of conduct and evaluation of (hetero)sexual conduct, and its indicators multiplied. At the end of the twentieth century, experimental research noted the weakening of the standard when inquiring about the permissiveness of respondents (e.g., sexual behavior vs. relationship type/phase) or the desirability of more- or less-experienced targets as partners (Crawford & Popp, 2003). At the same time, qualitative research pointed to the continued presence or recognition of the SDS in the labeling of experienced or so-perceived women – good girls vs. bad girls (Crawford & Popp, 2003). At the turn of the millennium the picture was not much different. A greater preference for liberal standards (e.g., pre-marital sex, sex without commitment) coexisted with a weakened but persistent SDS observable, for example, in the health discourses and social interactions of adolescent and young college students (Bordini & Sperb, 2013). The merit of these early twenty-first century investigations lay in demonstrating the variable nature of the SDS and of what may explain it, including culture, behavior and the characteristics of those who assess and are assessed (Bordini & Sperb, 2013). The qualitative works are demonstrative of the coexistence of positions that resist the SDS (e.g., predatory and promiscuous femininity vs. emotional and relational masculinity) and those that recognize, accommodate, and identify with the SDS (e.g., casual sex, children of different fathers), especially among women (Bordini & Sperb, 2013). A particularly important group of quantitative studies found that, for casualness and multiple partners, the SDS appears to be socially recognized rather than personally accepted (Marks & Fraley, 2005; Milhausen & Herold, 2001; Ramos et al., 2005), and may be automatically activated, even as it is explicitly rejected (Marks, 2008; Marks & Fraley, 2006, 2007). Such results are repeated and reinforced thereafter. The SDS is recognizable in media discourses (e.g., of femininity vs. responsibility and danger, and masculinity vs. pleasure and risk); it manifests in adolescent dynamics outside or within social media networks (e.g., sexualized photos); it may also be recognized and accommodated even if a liberal SSS is preferred, with young people seeking to distance themselves from practices such as casualness or partner swapping, which they know are more sanctioned in women and which they assume can also condemn men (Amaro et al., 2021b). It also manifests itself in the evaluations that youth, adults, and college students make about involvement in casual sexual relationships or hookups, sharing space with the various alternative patterns (Amaro et al., 2021b). The review by Endendijk et al. (2020) which is concerned exclusively with experimental research (questionnaires, scales, and vignettes), and which is in fact the most complete for this type of study, is in line with what has been said so far – the SDS being particularly evident for the questions of sexual coercion, casual sex, and sexual initiation – but goes on to underline two issues of the greatest relevance. First, it recognizes that the content of the SDS has changed and that it is now less of a personally-endorsed standard (personal SDS) than a socially-recognized shared belief (social SDS), although this distinction has only gained prominence in recent years. The study then notes how research with Likert-type-scale questionnaires not only provides no evidence of the (personal) SDS but also presents somewhat different results depending on the instrument used, raising concerns about the weaknesses of standardized measures (e.g., content, formulation, and scoring of items).

In sum, the research in recent decades demonstrates that the SDS has withstood the test of time and is still a strongly-rooted gender norm reflecting and reinforcing inequality in heterosexual relationships (Amaro et al., 2021b; Bordini & Sperb, 2013; Crawford & Popp, 2003; Endendijk et al., 2020; Lamont, 2021). Offering a first strong argument for further investing in the comprehension of the SDS, it also notes that a more thorough understanding of the standard demands methods that take the bi-dimensionality and dynamic nature of the concept into account, toward up-to-date ways of operationalizing and measuring it (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2020; Bordini & Sperb, 2013; Crawford & Popp, 2003; Endendijk et al., 2020). Conceptual and methodological limitations of previous research thus offer some clues as to what future research should look for, and guide as well as justify the objectives of this work – to develop and validate a measure of personal SDS that may be after adapted for evaluation of the social SDS, using Portuguese samples.

A second argument for continuing study of the SDS is furnished by the evidence that both personal and social SDS have the potential to interfere with men’s and women’s sexual reputation, freedom, health, and well-being (Alvarez et al., 2021b; Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2020; Amaro et al., 2022; Farvid, 2018; Fasula et al., 2014; González-Marugán et al., 2021). Men still gain social status from their involvement in casual sex or with multiple sexual partners, while liberal, active women continue to be negatively labelled (e.g., easy, slut), less desired for committed relationships, stigmatized, or even exposed to sexual victimization (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2020; González-Marugán et al., 2021; Marks et al., 2018; Minello et al., 2020; Rodrigue & Fernet, 2016). In the same vein, men who do not express their sexuality in an active, imposing manner may put their masculinity and sexual reputation at risk, while conformity with the SDS would protect women’s image and reputation, forestalling the negative consequences of transgression (Amaro et al., 2021a; Fasula et al., 2014; Kalish, 2013; Soller & Haynie, 2017). Compliance comes with its own costs. For women, the SDS has been shown to increase the risk of unprotected sex (Danube et al., 2016) and the likelihood of silencing sexual needs or preferences (Fasula et al., 2014; Jackson & Cram, 2003). It also increases the risk of complying with partners’ expectations despite costs, like unpleasant sexual activities (Fasula et al., 2014; Impett & Peplau, 2003; Petersen & Hyde, 2010) and of the likelihood of sexual passiveness, which has been associated to poor satisfaction and sexual problems (Amaro et al., 2022; Sanchez et al., 2012). For men, acceptance or recognition of the SDS has been associated with (pressure toward) promiscuous, unsafe, or unsought sexual activity that proves masculinity (Berkowitz, 2011; Kalish, 2013; Soller & Haynie, 2017). Masculinity has been associated with risk of poor sexual inhibition due to fear of performance failure (Clarke et al., 2015), while the emphasis on performance explains the strong preoccupation of men with the demonstration of competence through achieving and giving female partners an orgasm, which can lead to a less positive or satisfactory sexual experience (e.g., Chadwick & van Anders, 2017; Salisbury & Fisher, 2014).

Restrictive, punitive, and potentially deleterious to the sexual health of young men and women, particularly of university students, the SDS remains a reality in Western countries (e.g., Amaro et al., 2021b; Bordini & Sperb, 2013; Crawford & Popp, 2003; Endendijk et al., 2020), including Portugal, where the present study was developed. Portuguese research aligns with the general evidence on the SDS, pointing to the prevalence of the social over the personal SDS (e.g., casual sex, multiple partners) mostly in samples of university students (Alvarez et al., 2021a, b; Amaro et al., 2021a; Marques et al., 2013; Neves, 2016; Ramos et al., 2005). It also shows that both personal and social SDS are associated with masculine sexual risk-taking (e.g., high number of partners, unsafe sex) and poor, undervalued, sexual satisfaction for women in casual relationships (Amaro, et al., 2022; Frias, 2014; Zangão & Sim-Sim, 2011). However, the number of studies conducted in Portugal so far is low, while research on the personal SDS has mainly used adaptations of scales or questionnaires developed in other countries and with important limitations, as shall be discussed below, justifying the objective of the present work as well as the choice of population and samples.

For various decades, review works have highlighted the limitations of the methods used to study the SDS (e.g., Bordini & Sperb, 2013; Crawford & Popp, 2003); some have specifically noted the weaknesses of existing scales and questionnaires and the need to develop new standardized measures of the SDS (Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2020; Endendijk et al., 2020), as is the goal of present study. First, the fluidity and changeability of the SDS calls into question the accuracy of existing psychometric instruments, especially of those developed some years ago, demanding new, up-to-date measures. Secondly, investigation tends to focus more on the personal than on the social SDS, seldom comparing between these dimensions, and most of the existing psychometric instruments are measures of the personal SDS, a situation that calls for “hybrid” measures that evaluate both dimensions through equivalent indicators. Three of the five known measures assess the personal SDS only – the Double Standard Scale (DSS; Caron et al., 2011), the Sexual Double Standard Scale (SDSS; Muehlenhard & Quackenbush, 2011), and the Scale for the Assessment of Sexual Standards among Youth (SASSY, Emmerink, et al., 2016). Of the remaining two, the Questionnaire for the Evaluation of Sexual Double Standard (Milhausen & Herold, 2001) distinguishes between contexts of SDS manifestation, social SDS being one of its five dimensions but measured through indicators different from those used for the exploration of the personal SDS. The other consists in a subscale form of a sexual socialization measure developed by Levin et al. (2012) that evaluates communication of sexual values as one particular expression of the social SDS, but does not offer any information on the personal SDS. Thirdly, the existing measures contain several weaknesses (e.g., Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2020; Endendijk et al., 2020), namely indicators that are out-of-date, at least in Western contexts (e.g., It is just as important for a man to be a virgin when he marries as it is for a woman), unspecific, vague items (e.g., Boys and girls want completely different things in sex), items that fail to capture the judgmental, comparative, nature of the concept (e.g., Men think about sex all the time), or measurement scales that are unique to the SDS, i.e. that do not provide information on alternative standards. Methodological limitations thus complete the arguments in favor of the study of the SDS and of new research toward a scale to measure this traditional sexual standard.

In sum, the reasons for conducting the present study include the persistence of the SDS among young Western (and Portuguese) college students, the scarcity of studies conducted in Portugal, the negative relation between this traditional standard and (hetero)sexual health, the challenges posed to quantitative research by the bidimensional and dynamic character of the SDS, and the weaknesses of the methods that have been used to assess it so far, particularly the standardized measures. This study sought to develop a measure of contemporary personal SDS that could easily be adapted to assess the social SDS, as well as to evaluate and confirm the factor structure of the scale and its reliability, to test factorial invariance across gender, and to study its convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity, among samples of Portuguese college students,

Material and method

Participants

Two samples were drawn from 481 graduate and undergraduate college students from various Portuguese universities (e.g., 52% Central Region, 32% Lisbon Region, 13% South Region) and majors (e.g., psychology, sport, social service, engineering, computer science, law).

Sample A was composed of 209 individuals between 18 and 32 years of age (M = 20.5 years; SD = 2.3), of whom 25% were men, 97.1% were single, and 93.3% were heterosexual. In terms of academic qualifications, of the 198 that answered the question, 155 were undergraduates (78.3%) and 43 were graduate students (21.7%). A power analysis using WebPower (Zhang & Yuan, 2018) indicated this sample size is powered at 0.84, assuming a hypothetical measurement factor analytical model with df = 19, p < 0.05, and RMSEA = 0.05 for accepting the fit to the data (and rejecting at RMSEA > 0.10).

Sample B was composed of 272 individuals between 18 and 35 years of age (M = 20.9 years; SD = 2.9), of whom 43.4% were men, 97.4% were single, and 89.4% were heterosexual. In terms of academic qualifications, of the 260 that answered the question, 222 were undergraduates (85.4%) and 38 were graduate students (14.6%). A power analysis indicated this sample size is powered at 0.93 for a Confirmatory Factor with df = 19, p < 0.05, and RMSEA = 0.05 for accepting the fit to the data (and rejecting at RMSEA > 0.10).

Research and design

We used a cross-sectional research design in which we first created the initial poll of items for the New SDS scale through three different strategies from three different sources: (i) construction of items from a focus group study examining the SDS among college students; (ii) content validity analysis of the items by five experts in sexology; and (iii) comprehensibility of the items and response scale by four PhD students in psychology. The 19 items obtained were subjected to two cross-sectional studies – one for the exploratory factor analysis and the other for its confirmation – with data collected from college students face-to-face and online.

Procedures

The initial pool of items was developed through a number of steps and analyzed in terms of their content validity. First, a set of 20 items were developed based on information collected in a previous focus group study that took place to explore the perceptions of Portuguese college students about the SDS in the university context (Amaro et al., 2021a). The items that were developed reflected the observed recognition of the SDS regarding involvement in casual sex and multiple sexual partners and other sexual activities such as masturbation, use of sex toys, and use of pornography. The items asked mainly about the (un)equal acceptance of these sexual practices for men and for women, but also included questions about how individuals judge those involved in some particular sexual conducts (e.g., higher/lower admiration or more/less reservations regarding individuals’ character), forming a total of 20 items designed to evaluate individuals’ personal endorsement of the SDS.

The 20 items were revised by expert academics in sexology (n = 5) for the appropriateness of the content of the items for measuring SDS and the suitability of the response scale, and by PhD students in the field of psychology (n = 4), who mainly contributed in evaluating the comprehensibility of the formulation of the items. Two of the 20 items were considered redundant in terms of content, leading to the exclusion of the one perceived to be less effective for the purpose of exploring the SDS. The remaining 19 items were then subjected to small language adjustments replacing terms or expressions, and rephrasing items whose formulation the group of experts considered hindered the interpretation of the question.

The final pool of 19 items was launched in a study with seven other instruments (total of eight instruments with a total of 98 items) aiming to address the new scale validity and reliability parameters. After the approval of the study by the Ethics Committees of the institutions involved, data were collected in classes (by paper and pencil) and online. We requested the collaboration of colleagues teaching in different Portuguese universities in recruiting participants from their classes, and continued the recruitment online, using Qualtrics XM (https://www.qualtrics.com). Requests for participation were shared by e-mail and through social networks directly with potential participants and with authors’ contacts that could reach participants by professional or social association. In paper-and-pencil data collection, all requests were accepted; researchers were present in different classes to inform about aim(s) of the study(ies) and the conditions of participation and to collect data. In online data collection, requests for participation, accompanied by study purposes and conditions, and the URL to access the consent form and survey webpage were presented by e-mail and advertised through social networks. Those that agreed to participate were asked to read and sign or confirm consent before completing the survey in class (n = 404) or online (n = 138).

Sampling was non-probabilistic (snowball system), and after applying the inclusion criteria: (i) age between 18 and 35 years old, (ii) native Portuguese speakers; (iii) completion of at least 80% of the survey, the sample was reduced from 542 to 481 participants. Confidentiality and anonymity were guaranteed.

Measures

Participants answered a questionnaire with the new SDS scale and instruments used to analyze its convergent-discriminant and concurrent validity. The survey began with the scale under study and finished with a sociodemographic questionnaire; between these, the seven other instruments used to study convergent-discriminant and concurrent validity appeared in the order presented below.

New SDS scale

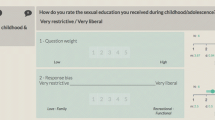

The 19 items first considered to assess personal SDS on the new scale (see Supplementary Online Material) asked about the acceptance of types of sexual conduct (e.g., “Of whom do you more easily accept their involvement in frequent casual sexual relationships?”) and about the evaluation of those involved in some of them (e.g., “Who would you most admire for engaging in frequent casual relationships?”). Items are answered on a five-point Likert scale – (1) “Much more of women”, (2) “Of women”, (3) “Equally of men and women”, (4) “Of men”, (5) “Much more of men”. Scores vary between 1 and 5, and higher scores are indicative of the traditional SDS, whereas lower scores are indicative of a reversed Sexual Double Standard (reversed SDS), showing greater approval of women’s sexual conduct, while medium scores (those tending toward three) are indicative of a Single Sexual Standard (SSS), defining the equal acceptance and evaluation of men’s and women’s involvement in the types of sexual conduct under consideration.

Double Standard Scale (DSS)

The DSS is a 10-item instrument that measures the personal SDS (Caron et al., 2011). Items (e.g., A woman who is sexually active is less likely to be considered a desirable partner) are answered on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = strongly agree to 5 = strongly disagree) and a total score is obtained by summing the responses in the 10 items (total ranging from 10 to 50), with lower scores indicating greater acceptance of the SDS. Adequate reliability was observed in the original scale (α = 0.72) and in a Portuguese version (α = 0.85/total sample; α = 0.83/men α = 0.81/women), translated by Zangão and Sim-Sim (2011) from the Spanish version of Sierra et al. (2007). In the present study, the DSS also demonstrated adequate internal consistency (α = 0.82/0.80 for samples A/B).

Sexual Double Standard Scale (SDSS)

The SDSS is a measure of the personal SDS composed by 26 items answered on a 4-point Likert scale (from 0 = disagree strongly to 3 = agree strongly), of which six are individual items comparing men’s with women’s sexual behavior (e.g., I approve of a 16-year-old girl’s having sex just as much as a 16-year-old boy’s having sex), and twenty are paired items that ask about the acceptability of sexual behaviors for women and for men (e.g., I kind of admire a girl who has had sex with a lot of guys; I question the character of a man who has had a lot of sexual partners) (Muehlenhard & Quackenbush, 2011). A total score is obtained by summing the responses to the individual items and the ten-pair difference scores, ranging from 48 (SDS), to zero (SSS), and to -30 (reversed SDS). Adequate or acceptable reliability was observed for the original scale (α = 0.73/women; α = 0.76/men), for a Portuguese version (α = 0.78) developed by Magalhães et al. (2007), as well as in the present study (α = 0.61/0.67 for samples A/B).

Brief Sexual Attitudes Scale (BSAS)

The BSAS is a short version of the Sexual Attitudes Scale (Hendrick & Hendrick, 1987) and is composed of 23 items and four subscales (Hendrick et al., 2006), among which is the 10-item subscale of sexual permissiveness (e.g., I do not need to be committed to a person to have sex with him/her) that original studies showed to have a Cronbach’s alpha higher than 0.90 (Hendrick & Hendrick, 2011). The sexual permissiveness subscale used in the present study was translated to Portuguese by Filipe (2012), and also demonstrated good reliability indices (α = 0.86). The subscale is answered on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = disagree strongly to 5 = agree strongly), and a total score is obtained by summing the responses to items (from 10 to 50), with higher scores indicative of permissive attitudes. Good reliability indicators were also observed in the current study (α = 0.88/0.90 for samples A/B).

Sexual Beliefs Scale (SBS)

The 20-item SBS short version is composed of five subscales measuring different rape-related beliefs (Muehlenhard, & Felts, 2011). The current study used the token refusal subscale, a measure of the belief that women often indicate they do not wish a sexual relationship when they do. The subscale consists of four items (e.g., Women often say No because they don’t want men to think they’re easy) rated on a 4-point Likert type scale (from 0 = disagree strongly to 3 = agree strongly). The total score is obtained by summing the responses to the items (from 0 to 12 points), with higher scores indicating greater acceptance of the token refusal belief. Good reliability indicators were observed for the subscale in the studies that gave rise to the SBS extended and short versions (α = 0.84 and α = 0.71, respectively), as well as in the current study (α = 0.73/0.78 for samples A/B).

Sexual Autonomy Scale (SAS)

The SAS represents a set of three items that Sanchez et al. (2005) adapted from an autonomy scale used in research about self-determination in relationships. The items measure the extent to which respondents feel their sexual behavior is self-determined (e.g., When I am having sex or engaging in sexual activities with someone, I feel free to be who I am), rated on a 7-point scale (from 1 = not at all true to 7 = very true). The scores vary between 3 and 21 points, higher values indicative of positive autonomy. An adequate Cronbach’s alpha was observed by the original authors (α = 0.75), as well as in the current study (α = 0.51/0.60 for samples A/B).

Sexual Knowledge and Attitudes Scale for Premarital Couples (SKAS-PC)

SKAS-PC is a measure of sexual attitudes (34 items; α = 0.81) and knowledge (33 items; α = 0.84) that comprises various subscales (Sadat et al., 2018). Among these, an eight-item subscale evaluating the knowledge about Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI) (e.g., People may have several STDs at the same time) was used in the present study, with an adaptation of the total score computation. Instead of a three-point scale (true = 1; false = -1; don’t know = 0), we used a true/false scale with right answers coded as 1 and wrong or absent answers coded as 0, such that higher scores indicated greater knowledge about STIs. Considering this adaptation, reliability was estimated through the split-half method (r = 0.40/0.55 for samples A/B).

Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI)

The TIPI is a brief measure of the Big-Five personality traits (extraversion – E, agreeableness – A, conscientiousness – C, emotional stability – S, and openness – O) developed by Gosling et al. (2003). Each dimension is represented by a pair of items rated on a seven-point scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree), and the scores correspond to the mean of the responses after recoding reversed items – higher/lower scores indicating the trait is more/less pronounced. Concerning reliability, due to the reduced number of items assessing each factor, internal consistency may be a less-accurate estimate, so its reliability has been assessed using test–retest correlations (Gosling et al., 2003). Temporal stability has been demonstrated for both the original TIPI (rE = 0.77; rA = 0.71; rC = 0.76; rS = 0.70; rO = 0.62) and for the Portuguese version developed by Nunes et al. (2018) (rE = 0.90; rA = 0.71; rC = 0.82; rS = 0.78; rO = 0.83). In the present study, correlations between items of each dimension were all significant (rE = 0.58/59; rA = 0.33/0.19; rC = 0.16/0.36; rS = 0.26/0.25; rO = 0.30/0.29 for sample A/B).

Sociodemographic questionnaire

The questionnaire asked about participants’ gender, age, sexual orientation, and level of education.

Data analysis

When constructing a new scale, the first step is to examine the dimensionality of the items through an exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Subsequently, it is important to test the measurement model found in the EFA in new samples by means of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and to investigate possible alternative hypotheses regarding the latent factor structure of the proposed new instrument. Sample A was used to conduct the exploratory study of the new SDS scale and Sample B to carry out the further confirmatory study of the structure obtained, as well as to test gender invariance, convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity.

An exploratory principal component analysis with oblique rotation (PCA) on the 19 items collected was conducted for the new SDS scale with Sample A. A parallel analysis (PA) was performed to better inform decisions on factor structure, with a set of criteria informing item removal, namely the exclusion of those that failed to include a component with three or more items or to reach a loading threshold of 0.40 or higher (e.g., Bollen, 1989). PCA was re-run until all the remaining items were in line with a combination of four criteria: 1) Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value above 0.70; 2) item communalities cut-off above 0.40; 3) no items with cross-loadings above 0.40 in two or more factors and with a difference lower than 0.30; 4) retention of factors with eigenvalues above 1 (e.g., Stewart et al., 2001; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007) and that were higher than mean eigenvalues generated by PA.

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was run using sample B in order to test the fit of the final structure of the PCA and to compare it with alternative models. The proposed factor structure goodness-of-fit was assessed by examining a number of indices, such as the chi-square/degrees of freedom (χ2/df), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Models were considered to have adequate fit with χ2/df under two, CFI and TLI equal to or above 0.90 (Bentler, 1990), and RMSEA below 0.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1998). Model comparison took into account the chi-square difference test (Bollen, 1989), the Bayesian information criteria (BIC) and the Akaike information criteria (AIC), with lower BIC and AIC suggesting more parsimonious solutions (Akaike, 1974; Kass & Raftery, 1995).

Reliability was examined by the Cronbach’s alpha (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994) and by the coefficients omega and omega hierarchical (Bell et al., 2023; Hayes & Coutts, 2020; McDonald, 1999; Rodriguez et al., 2016), with values between 0.70 and 0.80 indicating acceptable reliability and values equal to or above 0.80 illustrating a good level of reliability.

For the structure found, the gender invariance of the new SDS scale was tested using a multigroup data set, as suggested by Byrne (2010). A freely estimated structure where no equality constraints are imposed on any of the parameters (configural model) was compared to a constrained structure in which the factor loadings (metric model) and the intercept (scalar model) were estimated to be equal between groups. The models were compared using the chi-square (Δχ2) difference test, with the invariance of the scale between the groups being supported if the difference test was non-significant.

For convergent validity, the final version of the new SDS scale was expected to positively correlate with the SDSS and to negatively correlate with the DSS (as lower scores are indicative of SDS) and with the BSAS sexual permissiveness subscale. For discriminant validity, low or nonsignificant correlation was expected with the SKAS-PC subscale of knowledge on STIs and with each of the five dimensions of the TIPI. Finally, to explore concurrent validity, a linear regression was conducted to test how well the final version of the new SDS scale predicted views about token refusal (SBS) and sexual autonomy (SAS), which were expected to depend, to some extent, on the results of the former.

Data analysis was conducted in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 26, and AMOS, version 26.

Results

Descriptive data

Descriptive statistics for the items of the New SDS Scale are presented in Table 1. The means for each item ranged from 3.32 and 3.49, in a scale varying between 1 (reversed Sexual Double Standard) and 5 (SDS), thereby indicating a tendency towards an egalitarian Single Sexual Standard.

Exploratory analysis

The 19 items of the New SDS Scale showed a KMO of 0.73, which suggested a share of common variance and indicated that factor analysis could be performed for the set of items. Firstly, the PCA showed a six-factor solution explaining 64.2% of the total variance, whereas the PA showed a five-factor solution, pointing to a discrepancy that required further investigation of the items and the factors to retain. Based on the analysis of the resulting PCA pattern matrix, nine items were removed, of which eight were made up of factors with less than three items (four of six factors were composed by these items), and one failed to load above 0.40 in any of the six factors extracted. A subsequent PCA (KMO of 0.84) showed a two-factor structure with 10 items – five items in each component – explaining 54.5% of total variance. A discrepancy in the number of factors was found in comparing this solution with the one-factor solution indicated by the PA, requiring a detailed analysis of the PCA results. These showed that, despite all items loading above 0.45, one presented a cross-loading while another did not meet communality criteria, so these were excluded. A last PCA (KMO = 0.82) pointed to a two-factor structure consonant with PA results, and an eight-item solution that met all criteria, which explained 59.2% of total variance. Each component had four items and adequate reliability indicators (α = 0.81; ω = 0.82 and α = 0.69; ω = 0.69 for the first and second factors, respectively) (Table 1).

All the retained items reflected the theme of acceptability of sexual conduct, with the factors differentiating between sexual relationships and sexual actions and activities. Factor 1 reflected the positions adopted towards frequent casual sex, multiple partners, simultaneous partners, and affectively-detached relationships; Factor 2 reflected the positions adopted towards frequent masturbation, use of pornography, initiating casual sexual encounters, and assuming that one likes sex a lot.

Confirmatory factor analysis

CFA was run in order to test the fit of the bi-dimensional structure found in the PCA (Model 1) and to compare it with three alternative models – a unidimensional structure where all items measured a single factor (Model 2); a second-order factor structure where a latent factor accounted for the two first-order factors (Model 3); and a bifactor structure where each of the items loaded on a common general factor and on one of the two specific group factors (Model 4).

Results for the four factor models are presented in Table 2. The fit indexes for Model 2 were unsatisfactory. Model 1 and Model 3 presented similar adequate fit adjustments except for the χ2/df value, with model comparison showing non-significant differences, Δχ2(1) = 1.885, ns. Model 4 showed adequate fit indexes, χ2/df = 1.151; CFI = 0.997; TLI = 0.992; RMSEA = 0.024, and a significantly better adjustment compared with that of Model 1, Δχ2(7) = 14.07, p < 0.05, and Model 3, Δχ2(8) = 15.51, p < 0.05. The best adjustment of Model 4 was additionally corroborated by the AIC. The BIC and degrees of freedom favored the bidimensional and second-order models, however BIC is sensitive to the sample size while bifactor models tend to have fewer degrees of freedom as they are a more general model, with more paths to estimate (Dunn & McCray, 2020; Gignac, 2016; Reise et al., 2010).

Model 4 was retained, but required a re-specification, as a negative loading was observed for Item 4 in the specific group factor, warning that an alternative (S-1) bifactor model might better fit the data than the classical structure (Eid et al., 2017). We opted to exclude Item 4 from the group factor, but not from the general factor (Model 4A) and observed good fit indexes, χ2/df = 1.151; CFI = 0.995; TLI = 0.989; RMSEA = 0.028, and a better adjustment than Model 1, Δχ2(6) = 12.59, p < 0.05, and Model 3, Δχ2(7) = 14.07, p < 0.05. The final model thus considered a general common factor of SDS including all eight items first retained in the PCA, of which three loaded onto Factor 1, named the sexual relationships subscale, and four onto the Factor 2, the sexual actions/activities subscale (Fig. 1).

Reliability

The reliability estimates based on item scores were obtained independently for each dimension identified in Model 4A, with high internal consistency being observed both for the general factor of SDS (α = 0.78; CI 95% from 0.74 to 0.82) and the subscales for sexual relationships (α = 0.77/RL; CI 95% from 0.72 to 0.81), as well as for sexual actions/activities (α = 0.73/AC; CI 95% from 0.67 to 0.78). Likewise, coefficient omega based on CFA pointed to acceptable reliability for the subscales (ω S = 0.78/RL; ω S = 0.74/AC) and good reliability for the general factor of SDS (ω = 0.83), further reinforcing the adequacy of the components of Model 4A as measures of the SDS.

Because a bifactor model was retained, a set of additional measures/indexes was used to explore the adequacy of computing total and subscale scores. These included omega hierarchical (ꞶH) and omega hierarchical subscale (ꞶHS) defining: (a) “the percent of total score variance attributable to a single general factor; (b) the percent of subscale score variance attributable to a group factor, after removing the reliable variance due to the general factor” (Rodriguez et al., 2016, pp. 145,146). Other estimates included the construct replicability (H), where values from 0.70 were considered to be indicative of latent variables well represented by its indicators; the factor determinacy (FD), representing “the correlation of factor scores with factors”, for which values above 0.90 supported the use of factor scores estimates; and the explained common variance (ECV) of the general factor, where higher values are indicative of unidimensionality (Rodriguez et al., 2016, pp. 142–145).

The values of OmegaH (ω H = 0.58/SDS) and OmegaHS (ω HS = 0.42/RL; ω HS = 0.44/AC) were found to be relatively low, urging caution in interpreting the New SDS Scale’s total and partial scores. If, on one hand, relative omega, ECV, and FD do not support the use of total scores, on the other hand, they do not exclude the possibility of reporting them. For example, 69% of all reliable variance in total scores (ω H/ω = 0.69) and 51% of common variance (ECV = 0.51) were attributable to the general factor of SDS, which was also well represented by its indicators (H = 0.74) and highly correlated with the factor score (FD = 0.83), although below cutoff. Similarly, the difference between Omega and OmegaH showed that a quarter of the explained variance in the observed values was due to the specific factors (ω – ω H = 0.26), whereas ECV suggested 49% of common variance was spread among the subscales for sexual relationships (ω HS/ω S = 0.54; H = 0.58; FD = 0.75) and for sexual actions/activities (ω HS/ω S = 0.59; H = 0.57; FD = 0.74), both with half or more items loading close or above 5%. This means partial scores provided valuable insight on endorsement of the SDS, although its independent use was not fully supported.

Gender invariance

In order to evaluate factorial invariance across gender we first tested the bifactor S-1 model for women and men separately and found adequate fit indexes for both groups. Model comparison showed that the New SDS Scale, where all eight items share a common general factor of SDS, seven of which also load onto the sexual relationships or the sexual actions/activities subscales, was configural, metric, and scalar invariant across gender (Table 3). In addition, comparison of means scores across gender showed no significant differences for the global scale, t(242) = -1.122; p > 0.05, and for each of the subscales, t(256) = -1.514; p > 0.05/RL; t(231) = -0.205; p > 0.05/AC).

Convergent, discriminant, and concurrent validity

Correlations among scales are presented in Table 4. Convergent validity was demonstrated through the significant correlation of the New SDS Scale and its subscales with the DSS and the SDSS, in expected directions. No significant correlation was observed with the BSAS sexual permissiveness subscale, although the direction was negative as expected. Discriminant validity was also supported as the total score or subscales scores of the New SDS Scale did not significantly correlate with the STS’s knowledge subscale of SKAS-PC or most TIPI dimensions. There was also some evidence for concurrent validity, although the New SDS Scale and its subscales were shown to predict token refusal but not sexual autonomy (Table 5). The values of R2 showed that the general scale and the sexual action/activities subscales predicted 3% of variance in token refusal, respectively with F(1, 268) = 9.11 and F(1, 268) = 9.621, p < 0.005.

Discussion

The SDS is a dynamic, bidimensional, (hetero)sexual standard, whereas existing scales and questionnaires are usually unidimensional and contain out-of-date and unspecific items, among other weaknesses. We therefore sought to develop a new instrument for assessing the personal SDS that would overcome these issues and would also be flexible enough to allow for adaptation to measure the social dimension of SDS, as well as to measure the two dimensions within other groups and social contexts. We found consistent empirical evidence of factorial and convergent-discriminant validity, and some evidence of concurrent validity, for the New SDS Scale, which also shows itself to be sufficiently reliable and to be configural, metric, and scalar invariant between genders. The scale informs about the SDS and the other standards that may be preferred to it, namely an egalitarian Sexual Single Standard (SSS) or a male-critical reversed SDS. These alternative standards respectively occupy the center and the lower limit of an axis between one and five points, the latter representing SDS, and the average score obtained in this study points to the adoption of a SSS.

Development of the new scale

Concerning factor validity, the results of the PCA pointed to an eight-item solution organized in two factors – sexual relationships and sexual actions/activities. The sexual relationships factor represents non-romantic and non-exclusive (hétero)sexual involvements that have been shown to elicit the SDS, and the sexual action/activities factor depicts active expressions of sexuality that make differential evaluation more likely (e.g., Amaro et al., 2021b; Bordini & Sperb, 2013; Crawford & Popp, 2003; Endendijk et al., 2020). Indeed, the SDS has consistently manifested in the assessment of sexual relationships that are casual, unconventional (e.g., threesomes), or with multiple partners, (Alvarez et al., 2021a, b; González-Marugán et al., 2021; Marks et al., 2018; Minello et al., 2020), just as agency, sexual interest, masturbation, and pornography have been shown to set the stage for the SDS and gender asymmetries that reflect it (e.g., Fetterolf & Sanchez, 2015; Massey et al., 2021; Onar et al., 2020). The CFA rendered support to the two-factor structure found in PCA for the New SDS Scale and suggested a better fit of a bifactor S-1 comprising an eight-item general factor of SDS, a three-item sexual relationships and a four-item sexual action/activities subscales. Results indicate a relatively strong and reliable general factor and do support (or do not exclude) the plausibility of the subscales, which are also globally reliable. Model-based reliability estimates are below the cutoff, however they may be quite acceptable given the small number of items composing the scale and, particularly, each of the subscales. As such, the global scale and the subscales may be considered a reliable measure of the SDS and the alternative SSS and reversed SDS.

The general structure of the New SDS Scale proved to be equally valid for use with both men and women, and there were no significant gender differences for the SDS global scale and subscales, further supporting the adequacy of the new scale to the separate and comparative study of samples of men and women.

Convergent and discriminant validity are sustained, as the New SDS Scale and the subscales comprising it correlate with other measures of the personal SDS – the Double Standard Scale and the Sexual Double Standard Scale – and show weak or no correlation with constructs such as personality traits or knowledge about STIs. Correlations with convergent measures were not high, suggesting the New SDS Scale is in fact different from existing measures. Correlation between the SDS and sexual permissiveness was negative but not significant and did not support the demonstration of validity. One explanation for this might be the increasing distance between concepts – attitudes vs. judgment of sexual conduct – as there is evidence the SDS and gender influence is weakening with respect to women’s comfort with sex, a variable in close relation with sexual permissiveness (Marks et al., 2022; Seguino, 2016). Likewise, there was an unexpected correlation between extroversion and the sexual action/activities subscale (and the global New SDS Scale), that it was thought after as not necessarily strange because this personality trait has been positively related to sexual activity (Allen & Walter, 2018). Evidence for concurrent validity is weaker, however, since neither the New Scale nor its subscales predict sexual autonomy, and they only account for a small amount of the variance in token resistance scores. As is the case with unpredicted results, these may constitute a limitation to the conclusions on validity, but it is not impossible to interpret them. For example, the sexual autonomy responses may be referring to romantic relationships, whereas the new scale inquires about other types of relationships; the token resistance questions are questions about recognition and not so much about the acceptance of beliefs about gender differences.

Contributions of the new scale

Not all the validity tests led to the expected results, but there is strong conceptual and empirical support for using the scale as an appropriate measure of personal SDS. In addition to content validity based on the use of a qualitative study and a panel of experts, the factorial, convergent-discriminant, and (to a lesser extent) the concurrent validity of the New SDS Scale have been demonstrated, as have its reliability and factorial gender invariance. The psychometric properties of the scale therefore permit us to affirm that it is an adequate measure of SDS and that, unlike other measures, it provides information on the alternative standards that may be preferred when the SDS is rejected. The properties of the new scale also allow for the use and calculation of a general index and two specific indices of the SDS, which, together with the small number of items, will contribute to easier and more versatile application by different professionals, and in different contexts.

From a qualitative or conceptual point of view, the themes identified in the New SDS Scale – non-romantic and non-exclusive involvements and active expression of sexuality – represent an update of the existing instruments, and support the relevance of studies such as this one that aim to grasp the new contours that the concept is assuming and the respective ways of operationalizing and measuring it. In fact, the new scale identifies types of sexual conduct that elicit a personal SDS, some of which (e.g., pornography) are not considered in other scales and questionnaires, while it excludes types of conduct represented elsewhere that are no longer differentially accepted (e.g., premarital sex). On the other hand, all of the identified themes go along with what has been reported in the most recent literature on the manifestation of the SDS (e.g., Álvarez-Muelas et al., 2020; Amaro et al., 2021b; Endendijk et al., 2020), showing that the suggested update to the content of the standard has empirical support and aligns with what has been observed in other societies and cultures, which in turn indicates that the New SDS Scale has good prospects for generalizability. The dynamic nature of the concept and its anchoring in the concepts of gender roles and stereotypes, considered to be the conceptual basis of the standard (e.g., Amaro et al., 2021a; Fasula et al., 2014), are represented in the structure and content of the New SDS. The theme of non-romantic and non-exclusive involvements, referring mainly to stereotypes of emotional women vs. sexual men, and the theme of active sexual expression both especially concern gender roles and expectations. Beliefs such as that men have higher sexual desire than women, or that men are self- and orgasm-centered, whereas women are relation- and affection-centered, in association with the prescribed sexual roles (active male vs. passive female), would explain the manifestation of the SDS, or the “natural” entitlement of men, but not of women, to such types of involvements and expressions of sexuality (Amaro et al., 2021a; Fasula et al., 2014; Fetterolf & Sanchez, 2015; Petersen & Hyde, 2010, 2011; Sanchez et al., 2012). The emotional attachment item is particularly in line with the definition of the stereotypes, as affective bonds are one of the main criteria for distinguishing male and female sexuality, and can explain why the CFA came to isolate it as a general indicator of the SDS.

From a practical point of view, and in addition to the already mentioned advantages in terms of simplicity and versatility of application, the New SDS Scale could readily be adapted to the study of social SDS and, once the validity of this version is demonstrated, become the first two-dimensional measure of SDS. The adaptation could be accomplished simply by asking respondents to report on how they believe society judges the acceptability of the conducts for men and women. This will be of major importance because the social SDS, although still strongly-rooted, has been less studied and seldom considered by quantitative measures. The last major advantage of the new scale lies already in the product of its application, i.e. in the information it provides about the manifestation of the SDS, as well as about the relationship with sexual health and general well-being.

Implications for sexual health and well-being

In the present study, the mean score obtained for the New SDS Scale points to the adoption of an egalitarian, liberal standard. However, analysis of the frequency of responses shows that, for the totality of items, about 25% correspond to moderate acceptance of the SDS. As acceptance and recognition of the SDS have been associated with negative consequences for sexual health and general well-being, it is possible that young Portuguese are also exposed to risks by the influence of the SDS. Regarding sexual relationships represented in the first factor, transgressive female involvement usually leads to women being discriminated against, considered deviant, promiscuous, or less desirable for committed relationships (Alvarez et al., 2021b; González-Marugán et al., 2021; Jones, 2016; Rodrigue & Fernet, 2016). They also run the risk of feeling less respected by their partners, or having their pleasure placed second or devalued (Amaro et al., 2022; Brown et al., 2018; Kettrey, 2016). Male involvement in these relationships, on the other hand, is normative and proves masculinity; men may thus feel pressured into ultra-active or even risky sexuality. Research shows that the SDS not only has a positive relationship with the number of sexual partners (Soller & Haynie, 2017) and the frequency of casual partners (Holland & Vangelisti, 2020), but also that it is able to limit men’s sexual agency or to contribute to their involvement in unwanted or unprotected relations (Kalish, 2013). Regarding the actions/activities represented in the second factor, the SDS appears to place women at a particular disadvantage, with evidence that they inhibit or hide their sexual agency and experience for fear of negative evaluations (Fetterolf & Sanchez, 2015; Holland & Vangelisti, 2020); they experience masturbation as a less likely source of pleasure (e.g., shame/guilt) or well-being (e.g., body knowledge/pleasure) (e.g., Amaro et al., 2022; Carvalheira & Leal, 2013; Saliares et al., 2017); they avoid masturbating in the relationship in order to protect their partner's sense of masculinity or competence (Kraus, 2017; Onar et al., 2020); or they compete with pornography for intimacy, prioritizing their partner's needs (e.g., Ashton et al., 2020; Litsou, et al., 2021). As for men who frequently or compulsively use pornography and adopt sexist beliefs (e.g., dominant man, woman as object), they may not only experience diminished satisfaction with their bodies and difficulties in sexual functioning (Komlenac & Hochleitner, 2021; Massey et al., 2021), but may also disregard their partners’ desires, feelings, and consent, or engage in dominant, coercive, or degrading behavior toward women (e.g., slapping, hair pulling, penile gagging, spanking) (Massey et al., 2021). This is all the more serious given that sexual violence does not always qualify as such, under the guise of beliefs such as that women refuse desired sexual relations (token refusal) (e.g., Beres, 2010; Beres et al., 2014) or must reiterate refusal of a relation (or sexual practice), lest its absence be taken as consent (i.e., as “giving in”) (Hills et al., 2021; Muehlenhard, et al., 2016).

In sum, if the SDS and gendered sexual beliefs/norms have the potential to condition access to a free, safe, and satisfying (hetero)sexual experience, their manifestation warns of risks and asymmetries. The task of understanding and combating these may benefit from the study of SDS; this reinforces the value of the New SDS Scale as a means to explore acceptance (and, in the future, recognition) of the SDS and, combined with other measures, its effects on sexual health.

Limitations, strengths, and future directions

The current study has some limitations that must be addressed. Firstly, the independent use of the global New SDS Scale and subscales is not fully supported, meaning we cannot ensure the accuracy of the separate interpretation of scores. Based on the results, we can only recommend the joint analysis of total and partial scores, with subscales adding interpretative value to the total score (e.g., an apparent manifestation of the SSS may in fact hide a mixture of the SDS and the reversed SDS) and vice-versa. Secondly, concurrent validity is weak and deserves further inspection. Thirdly, the study relied exclusively on samples of college students and hence the suitability of the scale for young adults without university experience is unknown. Furthermore, as men made up only 25% of the sample of the exploratory study for the scale, the possibility cannot be ruled out that the selected items better reflect women’s perspectives of SDS than those of men. Finally, the generalizability for groups other than Portuguese college students is still not evidence-based, which calls for further studies with different populations. Research is also required to evaluate the suitability of the new scale for assessing the social SDS and to determine whether its psychometric parameters are also suitable for assessing the construct in other cultural contexts.

Strengths of the current study include the demonstration that the New SDS Scale is a valid, reliable, and gender-invariant measure of the personal SDS, plus the SSS and reversed SDS; the demonstration that the content of the SDS has been updated effectively; and the demonstration that operationalization of the construct has been made more efficient, for example, through items solely inquiring about the compared acceptability of sexual conducts for men and women. The new scale overcomes some of the limitations of existing measures, excluding outdated indicators of the SDS, controlling for other-construct indicators, and providing information on alternative standards. It shows itself to be sensitive to conceptual nuances, to reflect theoretical premises of SDS manifestation, and to align with evidence of the standard gathered in different Western societies. These observations, together with the small number of items and the conventional nature of the types of conduct they evaluate, are features that indicate that the New SDS Scale has good prospects for generalizability. Moreover, the small number of items, the simple computation of scores, and the bifactor structure comprising a general factor of SDS and two subfactors are characteristics that favor easy and versatile application of the scale. This may serve research in the field of sexuality, gender, and sexual health, as well as clinical and educational contexts. It can be a valuable instrument for exploring the sexual standards adopted by individuals or groups in general, or in the evaluation of particular sexual relationships or types of conduct. It can easily be adapted to measure the social SDS, allowing the comparison between personal endorsement and social recognition of the standard. And it can be easily combined with other measures to clarify if and how each dimension impacts sexual health and well-being, providing direction for sexual education and other interventions aiming to promote a free, positive sexual experience.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

Akaike, H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. In E. Parzen, K. Tanabe, G., & G. Kitagawa (Eds.), Selected papers of Hirotugu Akaike. Springer series in statistics (pp. 215–222). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-1694-0_16

Allen, M., & Walter, E. (2018). Linking big five personality traits to sexuality and sexual health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 144(10), 1081–1110. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000157

Alvarez, M.-J., Pereira, C., Godinho, C., & Luz, R. (2021a). Clear-cut terms and culture-sensitive characteristics of distinctive casual sexual relationships in Portuguese emerging adults. Sexuality & Culture, 25(6), 1966–1989. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-021-09859-0

Alvarez, M.-J., Pegado, A., Luz, R., & Amaro, H. (2021b). Still striving after all these years: Between normality of conduct and normativity of evaluation in casual relationships in college students. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/212144-021-02344-9

Álvarez-Muelas, A., Gómez-Berrocal, C., & Sierra, J. (2020). Relación del doble estándar sexual con el funcionamiento sexual y las conductas sexuales de riesgo: revisión sistemática. Revista Iberoamericana de Psicología y Salud, 11(2), 103–116. https://doi.org/10.23923/j.rips.2020.02.038

Amaro, H., Alvarez, M.-J., & Ferreira, J. (2021a). Portuguese college students’ perceptions about the social sexual double standard: Developing a comprehensive model for social SDS. Sexuality & Culture, 25(2), 733–755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09791-9

Amaro, H., Alvarez, M.-J., & Ferreira, J. (2021b). Manifestação do duplo padrão sexual nas sociedades ocidentais (2011–2017): uma revisão abrangente [Manifestation of the sexual double standard in Western societies (2011–2017): A scoping review]. Revista Crítica de Ciências Sociais, 124, 53–78. https://journals.openedition.org/rccs/11509

Amaro, H., Alvarez, M.-J., & Ferreira, J. (2022). Sexual gender roles and stereotypes and the sexual double standard in sexual satisfaction among Portuguese college students: An exploratory study. Psychology & Sexuality. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2022.2039271

Ashton, S., McDonald, K., & Kirkman, M. (2020). Pornography and sexual relationships: Discursive challenges for young women. Feminism & Psychology, 30(4), 489–507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353520918164

Bell, S., Chalmers, R., & Flora, D. (2023). The impact of measurement model misspecification on coefficient omega estimates of composite reliability. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 0(0), 104–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271627642800110

Bentler, P. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

Beres, M. (2010). Sexual miscommunication? Untangling assumptions about sexual communication between casual sex partners. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 12(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050903075226

Beres, M., Senn, C., & McCaw, J. (2014). Navigating Ambivalence: How Heterosexual Young Adults Make Sense of Desire Differences. Journal of Sex Research, 51(7), 765–776. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.792327

Berkowitz, A. (2011). Using how college men feel about being men and “doing the right thing” to promote men’s development. In J. A. Laker & T. Davis (Eds.), Masculinities in higher education: Theoretical and practical considerations (pp. 161–176). Routledge.

Bollen, K. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. Wiley.

Bordini, G., & Sperb, T. (2013). Sexual double standard: A review of the literature between 2001 and 2010. Sexuality & Culture, 17(4), 686–704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-012-9163-0

Brown, J., Schmidt, J., & Robertson, N. (2018). “We’re like the sex CPR dummies”: Young women’s understandings of (hetero)sexual pleasure in university accommodation. Feminism & Psychology, 28(2), 253–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353517742500

Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

Caron, S., Davis, C., Halteman, W., & Stickle, M. (2011). Double standard scale. In T. Fisher, C. Davis, W. Yarber, & S. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of sexuality-related measures (3rd ed., pp. 195–196). Routledge.

Carvalheira, A., & Leal, I. (2013). Masturbation among women: Associated factors and sexual response in a Portuguese community sample. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 39(4), 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2011.628440

Chadwick, S., & van Anders, S. (2017). Do women’s orgasms function as a masculinity achievement for men? Journal of Sex Research, 54(9), 1141–1152. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1283484

Clarke, M., Marks, A., & Lykins, A. (2015). Effects of normative masculinity on males’ dysfunctional sexual beliefs, sexual attitudes, and perceptions of sexual functioning. Journal of Sex Research, 52(3), 327–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.860072

Crawford, M., & Popp, D. (2003). Sexual double standards: A review and methodological critique of two decades of research. Journal of Sex Research, 40(1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490309552163

Danube, C., Norris, J., Stappenbeck, C., Davis, K., George, W., Zawacki, T., & Abdallah, D. (2016). Partner type, sexual double standard endorsement, and ambivalence predict abdication and unprotected sex intentions in a community sample of young women. Journal of Sex Research, 53(4–5), 601–613. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1061631

Dunn, K., & McCray, G. (2020). The place of the bifactor model in confirmatory factor analysis investigations into construct dimensionality in language testing. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1357. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01357

Eagly, A., Wood, W., & Johannesen-Schmidt, M. (2004). Social role theory of sex differences and similarities. In A. H. Eagly, A. E. Beall, & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The psychology of gender (pp. 269–291). The Guildford Press.

Eid, M., Geiser, C., Koch, T., & Heene, M. (2017). Anomalous results in G-factor models: Explanations and alternatives. Psychological Methods, 22(3), 541–562. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000083

Emmerink, P., Vanwesenbeeck, I., van den Eijnden, R., & Bogt, T. (2016). Psychosexual correlates of sexual double standard endorsement in adolescent sexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 53(3), 286–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1030720

Endendijk, J., van Baar, J., & Dekovi, M. (2020). He is a stud, she is a slut! A meta-analysis on the continued existence of sexual double standards. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 24(2), 163–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868319891310

Farvid, P. (2018). Sexual stigmatization. In T. K. Shackelford & V. A. Weekes-Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of evolutionary psychological science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16999-6_2457-1

Fasula, A., Carry, M., & Miller, K. (2014). A multidimensional framework for the meanings of the sexual double standard and its application for the health of young black women in the U.S. Journal of Sex Research, 51(2), 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.716874

Fetterolf, J., & Sanchez, D. (2015). The costs and benefits of perceived sexual agency for men and women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 961–970. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0408-x

Filipe, A. (2012). Abertura à experiência, atitudes e comportamentos sexuais em jovens do ensino superior (Dissertação de Mestrado em Sexualidade Humana). Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Lisboa.

Frias, A. (2014). Duplo padrão sexual e contraceção nos adolescentes. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 1(1), 359–368. https://revista.infad.eu/index.php/IJODAEP/article/view/381

Gignac, G. (2016). The higher-order model imposes a proportionality constraint: That is why the bifactor model tends to fit better. Intelligence, 55, 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2016.01.006

González-Marugán, E., Castaño, M., de Miguelsanz, M., & Antón, L. (2021). Are women still judged by their sexual behaviour? prevalence and problems linked to sexual double standard amongst university students. Sexuality & Culture, 25, 1927–1945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-021-09857-2

Gosling, S., Rentfrow, P., & Swann, W. (2003). A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 504–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1

Hayes, A., & Coutts, J. (2020). Use Omega rather than Cronbach’s alpha for estimating reliability. But…, Communication Methods and Measures, 14(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2020.1718629

Hendrick, S., & Hendrick, C. (1987). Multidimensionality of sexual attitudes. Journal of Sex Research, 23(4), 502–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224498709551387

Hendrick, S., & Hendrick, C. (2011). Sexual attitudes scale and brief sexual attitudes scale. In T. Fisher, C. Davis, W. Yarber, & S. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures (3rd ed., pp. 71–74). Routledge.

Hendrick, C., Hendrick, S., & Reich, D. (2006). The brief sexual attitudes scale. Journal of Sex Research, 43(1), 76–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490609552301

Hills, P., Pleva, M., Seib, E., & Cole, T. (2021). Understanding how university students use perceptions of consent, wantedness, and pleasure in labeling rape. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50(1), 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01772-1

Holland, M., & Vangelisti, A. L. (2020). The sexual double standard and topic avoidance in friendships. Communication Quarterly, 68(3), 306–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/01463373.2020.1787476

Howard, J., & Hollander, J. (1997). Gendered situations, gendered selves: A gender lens on social psychology. SAGE Publications.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

Impett, E., & Peplau, L. (2003). Sexual compliance: Gender, motivational and relationship perspectives. Journal of Sex Research, 40(1), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490309552169

Jackson, S., & Cram, F. (2003). Disrupting the sexual double standard: Young women talk about heterosexuality. British Journal of Social Psychology, 42(1), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466603763276153

Jones, D. (2016). The “chasing Amy” bias in past sexual experiences: Men can change, women cannot. Sexuality & Culture, 20, 24–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-015-9307-0

Kalish, R. (2013). Masculinities and hooking up: Sexual decision-making at college. Culture, Society & Masculinities, 5(2), 147–165. https://doi.org/10.3149/CSM.0502.147

Kass, R., & Raftery, A. (1995). Bayes factors. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 90(430), 773–795. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1995.10476572

Kettrey, H. (2016). What’s gender got to do with it? Sexual double standard and power in heterosexual college hookups. Journal of Sex Research, 53(7), 754–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1145181

Komlenac, N., & Hochleitner, M. (2021). Heterosexual-identified men’s endorsement of masculinity ideologies moderates associations between pornography consumption, body satisfaction and sexual functioning. Psychology & Sexuality, Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2021.1936616

Kraus, F. (2017). The practice of masturbation for women: The end of a taboo? Sexologies, 26(4), e35–e41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sexol.2017.09.009

Lamont, E. (2021). The persistence of gender dating. Sociology Compass, 15(11), e12933. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12933

Levin, D., Ward, L., & Neilson, E. (2012). Formative sexual communications, sexual agency and coercion, and youth sexual health. Social Service Review, 86(3), 487–516. https://doi.org/10.1086/667785

Litsou, K., Graham, C., & Ingham, R. (2021). Women in relationships and their pornography use: A systematic review and thematic synthesis. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 47(4), 381–413. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2021.1885532

McCarthy, B., & Bodnar, L. (2005). The equity model of sexuality: Navigating and negotiating the similarities and differences between men and women in sexual behavior, roles and values. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 20(2), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681990500113229

Magalhães, E., Chaves, S., & Nogueira, C. (2007, October, 25–26). Escala de Duplo-Padrão Sexual: Validação e diferenças de género numa população de estudantes universitários portugueses [Conference session]. I Congreso Galego da Mocidade Investigadora, Santiago de Compostela, Spain. https://www.usc.es/gl/congresos/congresos/2007/congreso_0061.html

Marks, M. (2008). Evaluations of sexually active men and women under divided attention: A social cognitive approach to the sexual double standard. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 30(1), 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973530701866664

Marks, M., & Fraley, C. (2005). The sexual double standard: Fact or fiction? Sex Roles, 52(3–4), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-1293-5

Marks, M., & Fraley, R. (2006). Confirmation bias and the sexual double standard. Sex Roles, 54(1–2), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-8866-9

Marks, M., & Fraley, R. (2007). The impact of social interaction on the sexual double standard. Social Influence, 2(1), 29–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510601154413

Marks, M., Young, T., & Zaikman, Y. (2018). The sexual double standard in the real world: Evaluations of sexually active friends and acquaintances. Social Psychology, 50(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000362

Marks, M., Busch, T., & Wu, A. (2022). The relationship between the exual double standard and women’s sexual health and comfort. International Journal of Sexual Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2022.2069179

Marques, N., Vieira, R., & Pechorro, P. (2013). The sexual double standard in a masculine way: A Portuguese transgenerational perspective. Revista Internacional De Andrología, 11, 138–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.androl.2013.06.001

Massey, K., Burns, J., & Franz, A. (2021). Young people, sexuality and the age of pornography. Sexuality & Culture, 25, 318–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09771-z

McDonald, R. (1999). Test theory: A unified approach. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Milhausen, R., & Herold, E. (2001). Reconceptualizing the sexual double standard. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 13(2), 63–83. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v13n02_05

Minello, A., Caltabiano, M., Dalla-Zuanna, G., & Vignoli, D. (2020). Catching up! The sexual behaviour and opinions of Italian students (2000–2017). Genus, 76(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-020-00085-4

Muehlenhard, C., & Felts, A. (2011). Sexual beliefs scale. In T. Fisher, C. Davis, W. Yarber, & S. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures (3rd ed., pp. 127–129). Routledge.

Muehlenhard, C., & Quackenbush, D. (2011). Sexual double standard scale. In T. Fisher, C. Davis, W. Yarber, & S. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of Sexuality-Related Measures (3rd ed., pp. 199–200). Routledge.

Muehlenhard, C., Humphreys, T., Jozkowski, K., & Peterson, Z. (2016). The complexities of sexual consent among college students: A conceptual and empirical review. The Journal of Sex Research, 53(4–5), 457–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1146651

Neves, D. (2016). Normas face ao género e à diversidade sexual: Mudanças inacabadas nos discursos juvenis. Sociologia, Problemas e Práticas, 82, 89–102. http://journals.openedition.org/spp/2506

Nunes, A., Limpo, T., Lima, C., & Castro, S. (2018). Short scales for the assessment of personality traits: Development and validation of the Portuguese Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI). Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 461. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00461

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory. McGraw Hill.

Onar, D., Armstrong, H., & Graham, C. (2020). What does research tell us about women’s experiences, motives and perceptions of masturbation within a relationship context?: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 46(7), 683–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2020.1781722

Petersen, J., & Hyde, J. (2010). A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality, 1993–2007. Psychological Bulletin, 136(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017504

Petersen, J., & Hyde, J. (2011). Gender differences in sexual attitudes and behaviors: A review of meta-analytic results and large datasets. Journal of Sex Research, 48(2–3), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2011.551851

Ramos, V., Carvalho, C., & Leal, I. (2005). Atitudes e comportamentos sexuais de mulheres universitárias: A hipótese do duplo padrão. Análise Psicológica, 23(2), 173–185. http://hdl.handle.net/10400.12/6024

Reise, S., Moore, T., & Haviland, M. (2010). Bifactor models and rotations: Exploring the extent to which multidimensional data yield univocal scale scores. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92(6), 544–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2010.496477

Reiss, I. (1956). The double standard in premarital sexual intercourse. A Neglected Concept. Social Forces, 34(3), 224–230. https://doi.org/10.2307/2574041

Reiss, I. (1960). Premarital sexual standards in America. The Free Press in Glencoe.

Rodrigue, C., & Fernet, M. (2016). A metasynthesis of qualitative studies on casual sexual relationships and experiences. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 25(3), 225–242. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.253-A6

Rodriguez, A., Reise, S., & Haviland, M. (2016). Evaluating bifactor models: Calculating and interpreting statistical indices. Psychological Methods, 21(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000045

Sadat, Z., Ghofranipour, F., Azin, S., Montazeri, A., Goshtasebi, A., Bagheri, A., & Barati, E. (2018). Development and psychometric evaluation of the sexual knowledge and attitudes scale for premarital couples (SKAS-PC): An exploratory mixed method study. International Journal of Reproductive BioMedicine, 16(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.29252/ijrm.16.1.41

Saliares, E., Wilkerson, J., Sieving, R., & Brady, S. (2017). Sexually experienced adolescents’ thoughts about sexual pleasure. Journal of Sex Research, 54(4–5), 604–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1170101

Salisbury, C., & Fisher, W. (2014). “Did you come?” A qualitative exploration of gender differences in beliefs, experiences, and concerns regarding female orgasm occurrence during heterosexual sexual interactions. Journal of Sex Research, 51(6), 616–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.838934

Sanchez, D., Crocker, J., & Boike, K. (2005). Doing gender in the bedroom: Investing in gender norms and the sexual experience. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(10), 1445–1455. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205277333

Sanchez, D., Fetterolf, J., & Rudman, L. (2012). Eroticizing inequality in the United States: The consequences and determinants of traditional gender role adherence in intimate relationships. Journal of Sex Research, 49(2–3), 168–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2011.653699

Seguino, S. (2016). Global trends in gender equality. Journal of African Development, 18(1), 9–30. https://doi.org/10.5325/jafrideve.18.1.0009